5 minute read

Business owners face uncertain future due to skill-games ban

BY MARK PAYNE | LINK nky GOVERNMENT & POLITICS REPORTER

Business owner Kama Reed is still determining how much longer she’ll own her business after a ban on skill games passed the Kentucky Legislature in the spring.

The law took effect on July 1.

The manufacturer of the games, Pace-OMatic, sued the state over the ban, but the case is stuck in the court system with the next hearing in August.

While the lawsuit plays out, businesses with skill games have been forced to shutter the machines until there’s final word.

Reed, who owns BJ Novelty in Covington with her husband, Jeff, faces an unlikely future after the ban of the games — often seen in gas stations and bars.

“This is a family company,” Reed said. “It was started in 1955 by my father-in-law, so we’re pretty much looking at a sale.”

BJ Novelty, which sits inside the old Johnny's Toys on Howard Litzler in Latonia, services the games and keeps track of them through a software program.

Most businesses say they earn around $2,500 to $5,000 monthly, according to Rep. Steve Doan, R-Erlanger, who introduced legislation in 2022 to regulate the games instead of banning them.

For Reed, though, that adds up for her company, as it has games in around 80 businesses in Boone, Campbell and Kenton

Counties.

“It has a great economic impact on my business and also on employment,” Reed said.

They hired four to six extra people to help, and now she thinks they might have to let them go.

What are skill games?

Skill games are gambling games that resemble slot machines and are often seen in bars and gas stations hidden to the side or

They’re often called “gray machines” because users don’t usually know if they’re legal or not, and opponents of the machines often label them as illegal gambling.

But, for those in support of them, they help provide some modest income for businesses.

Guy Cummins, the owner of Smokin’ This and That BBQ, said he usually makes enough off the machines to pay the electric bill.

“It’s usually right around 1,500 bucks, maybe something like that, about pays our electric bill,” Cummins said. “Now we’re a small restaurant, so we don’t have the revenue off of it that other places do.”

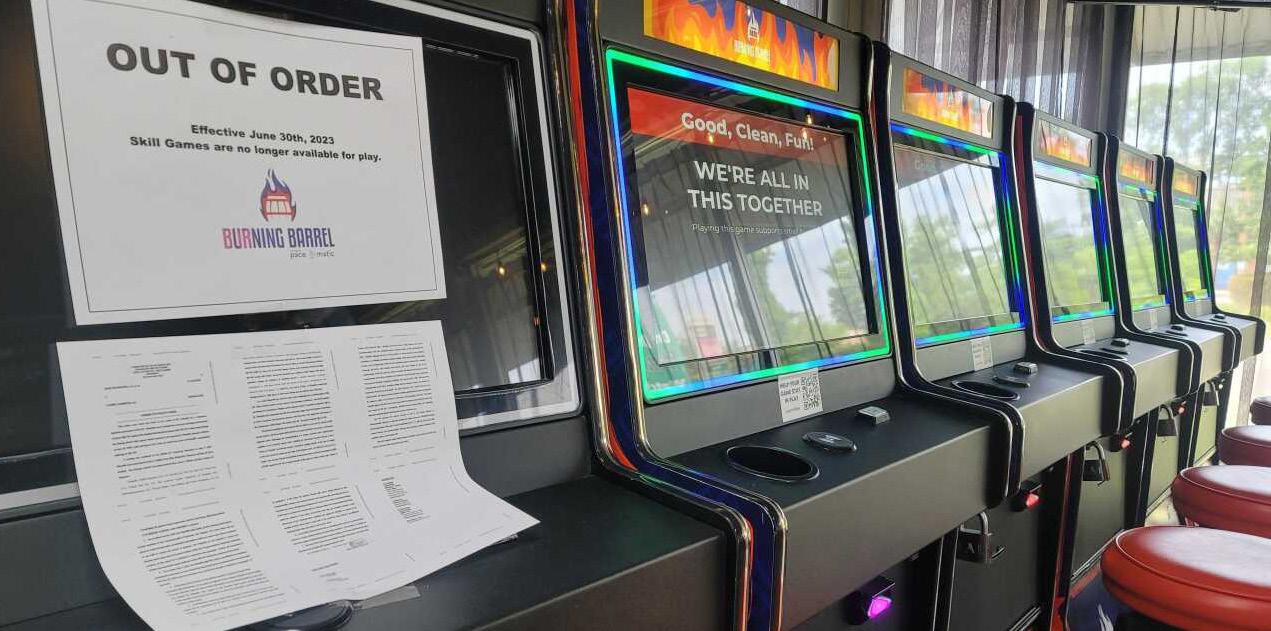

At Cummins’ restaurant, which is in Florence off Mount Zion Road, the machines now are turned toward the wall, have their operating components removed so they don’t work, and have signs that show they’re out of order.

“It’s not like there’s a line of people to play

Continues on page 8 them,” Cummins said. “It’s here and there. You know, kids don’t play it. We don’t allow it, and you got to be 21 to play ’em.”

Cummins said the extra funding helps him and other small-business owners. After the uncertainty they faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, where restaurants closed down to stop the spread of the virus, it might deliver the final death blow.

“I can’t even have two little machines in here to make a little money to pay my electric bill,” Cummins said.

Pace-O-Matic disabled the games at least a week early so it could double-check to make sure no games were operable.

How the legislation played out in the Kentucky Statehouse

In March, the Kentucky Legislature finalized the passage of House Bill 594 — the law banned “gray machines” — often referred to by supporters of the machines as “skill games” — throughout the state.

The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Killian Timoney, R-Nicholasville, said it would clarify what types of gaming devices are legal under Kentucky law. Currently, according to Timoney, Kentucky allows three types of gaming — lottery, charitable gaming and pari-mutuel gaming.

“Kentucky has always done an excellent job of regulating gaming, and we want to continue that effort now by outlawing illegal gaming machines,” Timoney said on the House floor earlier this year.

The bill took an unusual path, however. Initially brought for a vote on the House floor on March 3, the bill was tabled after some Republicans questioned if this was the best path.

Doan, who introduced a bill this session that sought to regulate and tax gray machines in House Bill 525, requested to table the bill.

“Today, we’re presented with a binary choice — a choice between Wild West unregulated gaming or an outright ban,” Doan said at the time. “Let me tell you, neither choice is right for Kentucky.”

Doan then presented a third choice — the regulation and taxation of the machines. In addition to Doan’s House Bill 525, another bill had been filed to accomplish the same goal, but they didn’t move in the 2023 session.

The following week, though, the House caucused for nearly two hours before returning to the floor and passing the bill with little discussion.

Further, opponents of the bill say it would allow the horse racing industry to monopolize the gambling industry in Kentucky.

“For one of the elephants in the room — yes, the racetracks have seen and contributed to the language,” Timoney said. “They don’t like all of it but are not opposing the bill. No, it is not a Churchill Downs bill.”

In the Senate, two NKY Senators — Chris McDaniel, R-Ryland Heights, and Shelley Funke Frommeyer, R-Alexandria, — voted against the bill. Sens. Damon Thayer, R-Georgetown, and John Schickel, R-Union, voted in favor of the bill.

Frommeyer said she voted “no” because it felt like skill games should be regulated and allowed to stay in place instead of being banned.

“I just felt like it wasn’t the right approach for our small businesses,” Frommeyer said at the time.

The battle over the bill also saw the state’s largest-ever lobbying effort. In the first four months of the year, lobbying interests spent $11.4 million, surpassing spending for the same period in 2022 with $11.1 million.

It’s important to note, though, that the Legislative session lasted only 30 days in 2023, whereas, in 2022, the legislature held a 60day budget session.

As of May, the top spender when it came to lobbying was KY Merchants and Amusement Coalition, Inc., which is an organization that consists of bars, restaurants and retailers that argue it rely on the games. They spent $483,324.

Kentuckians Against Illegal Gambling, which opposed the machines, spent $348,763.

Kentucky-based Pace-O-Matic was the fifth-biggest spender at $110,150.

While lobbyists spend record amounts, it could have political costs for Doan, who stood up to House leadership over the bill. Doan was removed from a committee assignment at the end of the session — in what some lawmakers see as punishment for speaking up.

“I had one member of leadership call and confirmed that I was removed from my committees because I stood up and I tabled that legislation,” Doan said. “It just goes to show you that, you know, you can fight the corporate interest on a campaign trail, and nobody has a problem with that.”

Doan further said there are consequences when you fight corporate interests in Frankfort and actually push back and do what’s best for the people of the state, though he said he’s undeterred by those consequences.

“They can’t take away my vote,” Doan said. “They can’t take away my ability to represent the 45,000 people in my district, and I’m gonna keep doing that, and whether they reinstate me or not, that’s up to them, but I’m gonna keep working hard.”

Real-life consequences

Reed recently turned 69 and said retirement has been running through her mind. She spent the last two winters in Frankfort lobbying against the ban on the machines.

Her husband grew up in Northern Kentucky, and she’s been here since 1976 — they met as students at Eastern Kentucky University.

“Been quite a while and love Kentucky,” she said, before saying she’s never been involved in politics, but “wow, this was an education.”

Two days after talking to LINK nky, Reed reported that she had sold her business and almost all of their employees would be joining Pioneer Vending Services.

“I will continue to advocate for small businesses, pubs, restaurants, bowling alleys, etc., to participate and enjoy skill games,” Reed said.