7 minute read

NKY makes space for Brent Spence overhaul, but not everyone is happy

BY NATHAN GRANGER | LINK nky CONTRIBUTOR

No part of this publication may be used without permission of the publisher. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings, and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please let us know and accept our sincere apologies in advance.

On The Cover

Photo illustration of the new Brent Spence Corridor footprint overlaid on top of the current highway. Image by James Robertson | LINK nky contributor

On Nov. 11, 2020, a semitruck heading northbound on the bottom deck of the Brent Spence Bridge jackknifed across the road at about 2:45 a.m. Another truck not far behind carrying industrial potassium hydroxide and diesel fuel collided with it and ignited an hourslong blaze, leading to the evacuation of both decks of the bridge.

Emergency crews managed to extinguish the fires without injury. Over a month and $3.5 million later, the bridge was completely repaired and back in operation.

“You take Main Street, right through Mainstrasse here, and it was just wall-to-wall traffic and semitrucks,” said Covington resident John Saxton.

The bridge fire and the subsequent repair efforts captured a lot of attention, but the added pressure on local communities due to the bridge’s closure didn’t generate the same kind of headlines.

If you go down to Main Street today, you’ll likely see delivery trucks parked on the street, bringing in food and other supplies for the businesses in the area. Most of the delivery trucks are smaller than tractor- trailers, but their presence crowds the roadways and sidewalks just the same.

“The city’s experience with the closure of that bridge showed the impact of diversion in a very real way,” said Covington Mayor Joe Meyer in an interview with LINK nky.

“It moved from the theoretical to being on the ground as thousands and thousands of cars a day got off the street, got off to the interstate and drove all over our city, creating a devastating impact on the quality of residential life and even the quality of commercial life.”

Bil Spencer, the president of the Residents of Mainstrasse Association, said the neighborhood would be unable to handle another influx of truck traffic. He pointed to sites in the borough recently damaged by trucks passing through.

Mainstrasse wasn’t the only area affected.

“Virtually every section of the city was impacted,” Meyer added, naming historical neighborhoods like Mutter Gottes, Seminary Square, Lewisburg and Licking Riverside.

“We had a famous incident where a semi- trailer following its GPS device went all the way down Greenup Street to the Ohio River,” Meyer said. “And then in his turnaround part he drove across the plaza there, knocked over a fire hydrant, knocked down a pole; a pole fell on a car. Just devastating.”

Residents are concerned that the start of the construction of the Brent Spence companion bridge will bring similar problems downtown. Predicted to begin at the end of the year, the project is estimated to take seven years to complete. Issues arising from the construction, such as traffic diversions as well as other issues like pollution, noise and residential displacement, have people on both sides of the river worried about the future.

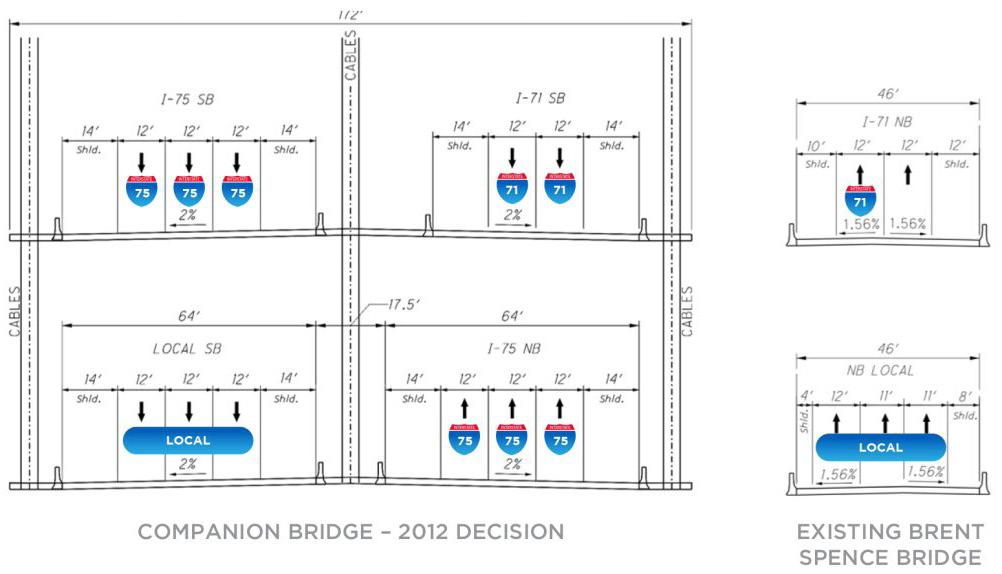

The Brent Spence Bridge overhaul project will encompass “corridor” and “companion” components. The corridor work will improve more than 8 miles of the heavily traveled Interstates 71/75 expanse, while the companion project will create a supplemental bridge to allow for separation of local and through traffic.

The original bridge went into operation in 1963, and ideas for the new companion

Continued from page 3 bridge and corridor project date back to the mid-2000s. A joint project between the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet and the Ohio Department of Transportation, the corridor has gone through multiple stages of development, redevelopment, public input and environmental study in the years since its inception.

Late last year, Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear and Ohio Gov. Mike Dewine announced an injection of $1.6 billion in federal funds into the project, a move commemorated in January when President Joe Biden, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.; former Ohio Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio; and Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio visited Covington to publicly endorse the project.

As LINK nky’s Business Reporter Kenton Hornbeck reported, the president’s visit cemented the inevitability of not only the construction of the new corridor but also its importance to the regional and national economy. The total price tag for the corridor is $3.6 billion, split between the two states, according to the project’s website.

Its initial design was settled on in 2012 after the first round of public input and an environmental study were completed.

After a series of revisions, the project has pitched two possible designs for the replacement bridge – a cable bridge design and an arch bridge design. Categorized as a progressive design-build project, the plans for the corridor are open-ended, allowing the designs to be augmented and changed based on public comment and environmental assessment as the construction proceeds.

The necessity of an overhaul of the Brent Spence Bridge has been widely touted regionally and nationally. The span is one of the most heavily traveled corridors in the country, with significant economic impact. It was designed to carry 60,000 vehicles a day but now handles twice that number, according to the Ohio Department of Transportation.

Although the companion bridge and its accompanying infrastructure have gone through numerous changes, many resi- dents still have concerns they feel haven’t been addressed.

Not by a long shot.

Some are concerned with how the seven-year (or longer, depending on how smoothly everything goes) construction of the corridor will affect people’s lives. What’s more, some are skeptical if the project as a whole is even necessary.

“It’s a gamble,” said Covington City Commissioner Nolan Nicaise. “Is it worth it?”

Nicaise is one of the project’s most strident critics.

“I am openly against the expansion of I-71/I-75, the Brent Spence corridor expansion project,” he said, “and I have many reasons for that.”

Nicaise has a background in environmental science and has consulted with cities throughout the country on environmental and zoning policy. As such, he’s particularly worried about the short- and long-term impacts the project could have on the environment and public health.

“As we know, pollution from vehicles is caused by the combustion of fossil fuels, but it’s also caused by the erosion of brake pads,” Nicaise said. “It’s also caused by the erosion of tires themselves, all creating particulates that are damaging to people in the vicinity, and also people further away as the wind blows.”

He’s also said he’s concerned about the cost of the project and questions whether the investment will pay off in the long run. He wonders if the money would be better spent elsewhere.

“Do we really want to be investing that money in a new highway, or do we want to be investing that money in something that is really a pride for this region?” Nic- aise asks. “So I think, how could we otherwise invest $3.6 billion? Could we create the most robust school system in America? Could we create a park that rivals Central Park? Could we create a transit system that is sustainable and equitable and people really enjoy taking and feel safe on?”

The funding for the bridge is a combination of federal and state money, most of which is earmarked specifically for infrastructure and similar measures. Although much of the funding for the project couldn’t be swapped outright for the projects Nicaise mentions, critics say it illustrates what they characterize as the lopsided priorities of federal and state projects.

Others share Nicaise’s concerns, even if they aren’t outright against the project.

Following the president’s visit in January, the Devou Good Foundation, a Northern Kentucky nonprofit dedicated to community infrastructure improvement, among other things, wrote an open letter to the Federal Highway Administration, titled “Concerns over Brent Spence Corridor Project’s Compliance with Civil Rights and Environmental Regulations,” which affirmed many of Nicaise’s concerns; the commissioner is one of the letter’s signatories.

The letter, penned by Dr. Ryan Crane, a Cincinnati-based physician who consulted with activists and professionals around the country, draws attention to both environmental and civil rights concerns by citing court cases and public statements from political leaders.

In addition to the pollution concerns that Nicaise mentioned, the letter talks about how federal highway projects have displaced and even destroyed majority Black and Latino communities throughout the 20th century.

Devou Good isn’t the only group worried about displacement.

One such group is the Bridge Forward Coalition, a Cincinnati nonprofit that, while not opposed to the project, is advocating for its own vision of the corridor. The group contends its version of the build would avoid many of the problems the region has experienced with the highway expansions of yesteryear. At a coalition event at the Cincinnati Museum Center in June, a panel of experts, several local leaders and members of the public discussed the gutting of Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood in the 1950s and 60s.

The construction of I-75 and the subsequent urban renewal campaign eventually led to the displacement of about 27,000 people, almost all of whom were Black, according to the late Cincinnati historian John W. Harshaw Sr., who wrote a book on the neighborhood’s history. To this day, the neighborhood’s population levels have not returned to the levels they were before the construction, and the highway has left the area carved up into smaller land parcels.

“We have an opportunity to work with our local form of government, with the federal government to do the right thing,” said West End resident and director of special initiatives for the Greater Cincinnati Foundation Robert Killins Jr., adding that the community ought to focus “not on the cost but on the value” of the project.

In other words, how can government leaders go about the project in such a way to benefit the local community, rather than narrowly focusing on controlling construction costs?

On the Kentucky side, Covington’s Lewisburg neighborhood went through a similar ordeal, although on a smaller scale.

Meyer furnished a map a 1936 Holmes High School drafting class created , which shows the geography of the city prior to the interstate’s incursion. He pointed to the areas in historical Lewisburg where the interstate