8 minute read

Whitehead Peter allen Press same car editor's in decline rudi tasmania mystery

The XK150 was the least like a competition model of the three types. However, still quite a few did race, including one by Don Thallon in Brisbane, Bill Hemming n Melbourne and Rudi Vanderelst in Geelong West. Each were fast, and here Rudi dodges the spinning XK120 RHD chassis #17.

A forgotten XK150 when near new was a FHC raced in Tasmania by Don Gorringe. Here it is being pressed hard at Longford by John Goss in the FJ Holden. Goss would be a Jaguar hero in years to come.

Advertisement

Like all models the XK150 went through a period of decline until they were valuable enough to spend the money needed for a restoration. This sad DHC was at XK Day in England in 1976, and no doubt is pristine now.

This new XK150 was constantly parked on the start/finish line at the Gnoo Blas racing track in Orange, NSW. We have no idea who owned it, or where it is now. We can see it is a 3.4 litre model and not an S. Can a reader help us solve that?

A U.S. READER ASKED US TO FEATURE

the XK150, and we agreed it was overdue. If you don’t know the model well you will to be surprised and impressed.

Many love it, some don’t - but we are with the former. We need to state up front, our editor and his family owned the ultimate XK150 variant - a late 3.8 litre S - for over 40 years. Naturally, we have indelible memories and a coloured view of it. Its purchase was inspired by the Darryl Matthews XK150S which spent most of its first 20 years in a vacuum sealed box, and was fitted with spare D-Type wheels from Bob Jane’s D-Type XKD532.

The XK120 came first, and entered the world in 1948. Its up-grade was the XK140 in 1955 which looked almost identical save for the heavy bumpers front and rear, plus a full wooden dash.

The XK150 had a leather covered dash, but wood or aluminium were an option - we have not seen either. It also came with revolutionary Dunlop disc brakes on all four wheels, a major safety breakthrough in 1957 and a wonderful selling point.

When it was introduced in May of that year the XK150 was a vastly different sporting Jaguar to earlier siblings. Larger, more luxurious and classically more modern in body design, it would be the last Jaguar sports car built on a traditional chassis, and ended up with a straight port headed 3.8 litre XK engine fitted with three SU carburettors. That unit would move straight on, untouched, to the legendary E-Type in 1961.

Initially the XK150 was only available in Fixed Head Coupé (FHC) and Drop Head Coupé (DHC) versions. The Roadster, without full weather equipment, was launched as the OTS (Open Two Seater) in 1958.

It was fitted for the first time with wind-up windows in taller high-silled doors, but retained the very simple folding roof of its predecessors.

Most visibly in all XK150s, a one-piece windscreen replaced the split screen. The widened bonnet opened down to the ‘guards, and on the Coupés the windscreen frame was moved forward four inches (102 mm) to make passenger access easier.

Thinner doors gave more interior space and a little red light reminded the driver that the front parking lights were on. It was located in a pod at the top of the mudguards.

Suspension and chassis were very similar to the XK140, with manual gearbox-only rack and pinion steering. The 3.4 litre XK engine was similar to the XK140’s, but a new B type cylinder head raised power to 180 SAE bhp at 5750 rpm.

Twin 1.75-inch (44 mm) SU HD6 carburettors and a modified B type cylinder head with larger exhaust valves improved performance to 210 SAE bhp at 5500 rpm. While most were SE models, a third option for the open twoseater featured the 3.4 litre S engine with power boosted to a claimed 250 SAE bhp.

In 1960 the 220 hp (164 kW; 223 PS) 3.8 litre engine, already fitted in the MkIX since October 1958, became standard. It was tuned to produce up to 265 hp (198 kW; 269 PS) in S models, and propel an XK150 to 135 mph (217 km/h) and from 0–60 mph in around 7.0 seconds.

Factory specification 6.00 × 16 inch Dunlop Road Speed tyres or optional 185VR16 Pirelli Cinturato CA67 radials could be fitted on either 16 × 5½ solid wheels or optional 16 × 5 wire wheels.

The rest of the up-grade pack included high lift camshafts, a 9.0:1 compression ratio, heavier torsion bars and twin exhausts. Wire wheels and fog lights were virtually standard.

As before, body panels were manufactured predominantly from steel. Exceptions were the bonnet and boot lid which were formed from aluminium.

Although the XK150 closely resembled its predecessors, Jaguar brought in a number of subtle but significant revisions to up-date it for its last few years of production.

The increased cabin space made access easier, while FHC and DHC variants came with a windscreen that was moved fourinches further forward.

Up front, the bonnet was widened and given a noticeably broader sixteen-bar instead of seven-bar grille. The new grille was identical to that added to the ‘Mk1’ when it got its 3.4 litre engine. The doors were now thinner to further increase cockpit space, and the FHC came with a larger curved rear window.

To reflect the extra space inside, subtly revised seats were installed. Once again, the FHC variant came with two small rear seats - which were really just loose cushions and next to useless.

The Special Equipment model was the one most people assume is standard, but in fact the standard XK150 had steel wheels, spats covering the rears and drum brakes as standard. All others, which was virtually all, were the Special Equipment (SE) model.

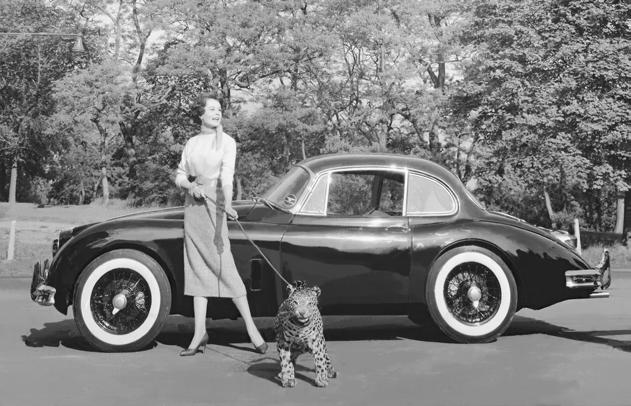

Buyers could have the exterior of their XK150 enhanced with Lucas fog lights, a leaping Jaguar mascot for the bonnet (rare), a chromed luggage rack for the boot, a chromed badge bar, Dunlop Road Speed tyres with whitewalls and steel wheels with chrome hub caps and rear wheel spats.

Performance up-grades included a closeratio gearbox and Dunlop racing tyres. A steel underbody shield gave protection against adverse road conditions.

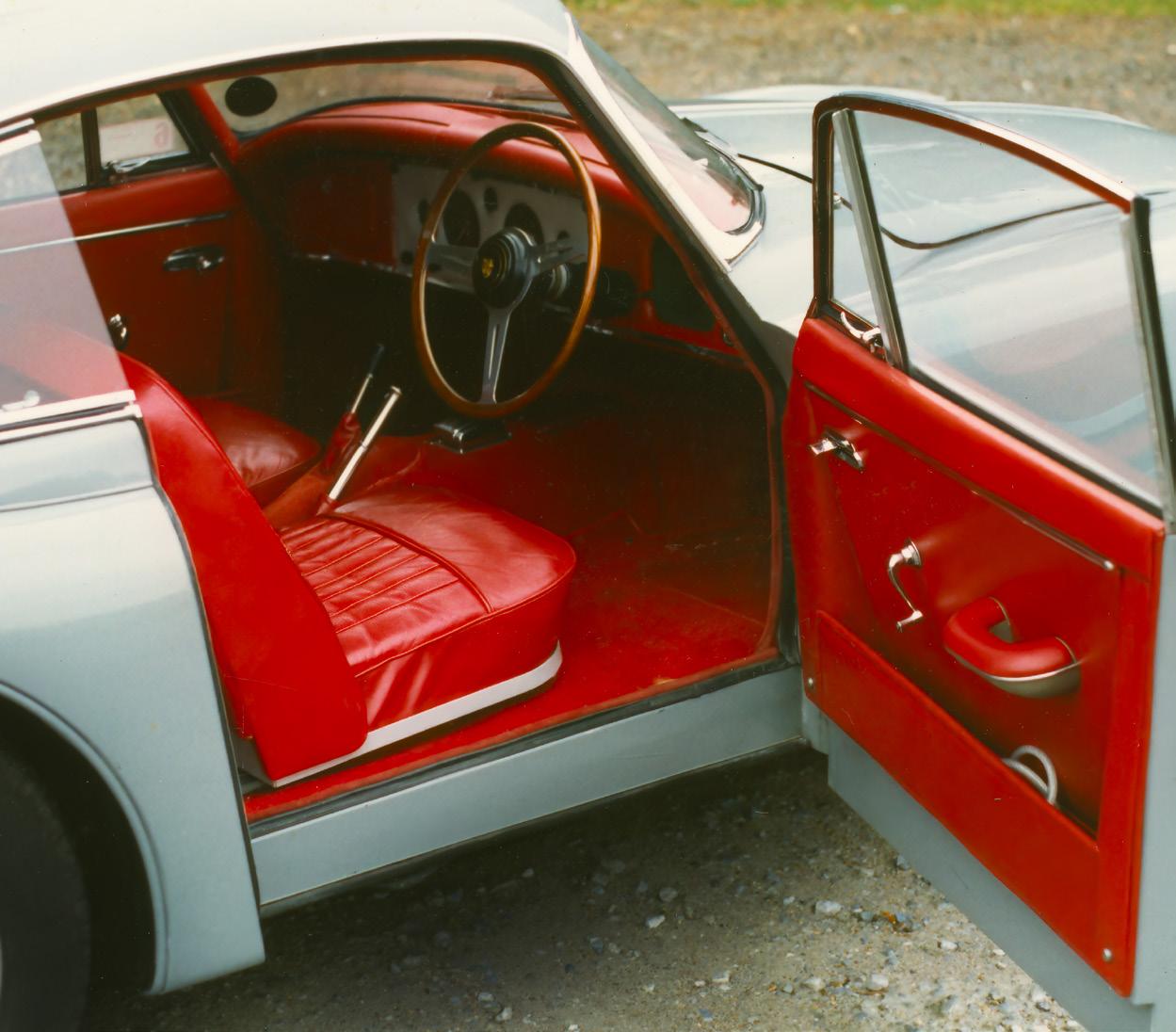

Cockpit extras included fitted luggage (two suitcases to match the rest of the interior), a choice of radios, an aluminium dash, bucket seats and a white or wood finished Bluemels steering wheel. The FHC could also be specified with a Weathershields sunroof and the DHC a full-length tonneau cover.

The XK150 FHC weighed in at 1473kg while the outgoing XK140s had both tipped the scales at 1420kg.

A departure from previous Roadsters was the addition of external push-button door handles.

As usual, this latest Roadster retained the simple folding roof of its predecessors. At 1447kg it was the lightest XK150.

The S engine was not available with an automatic gearbox - also something new for Jaguar’s sports car range. Cars ordered to S specification came with all the Special Equipment trim as standard.

Production changes made during 1958 included the discontinuation of the aluminium dash option, and the switch from 54 to 60-spoked wire wheels.

At the London Motor Show in October 1959, Jaguar launched the new 3.8-litre engines for the sports car, so now for an S

01

Very scarcely seen. Bob McKay's genuine RHD Roadster 3.8 XK150S Roadster in Brisbane.

02

Competitive against a former works Mk1 at Silverstone, this XK150 is a star on European tracks.

03

Probably the ultimate original XK150S, this is the ex-Leech and Matthews car which is untouched since new. It has been owned in Australia, England and New Zealand but is now back in Melbourne.

04/05

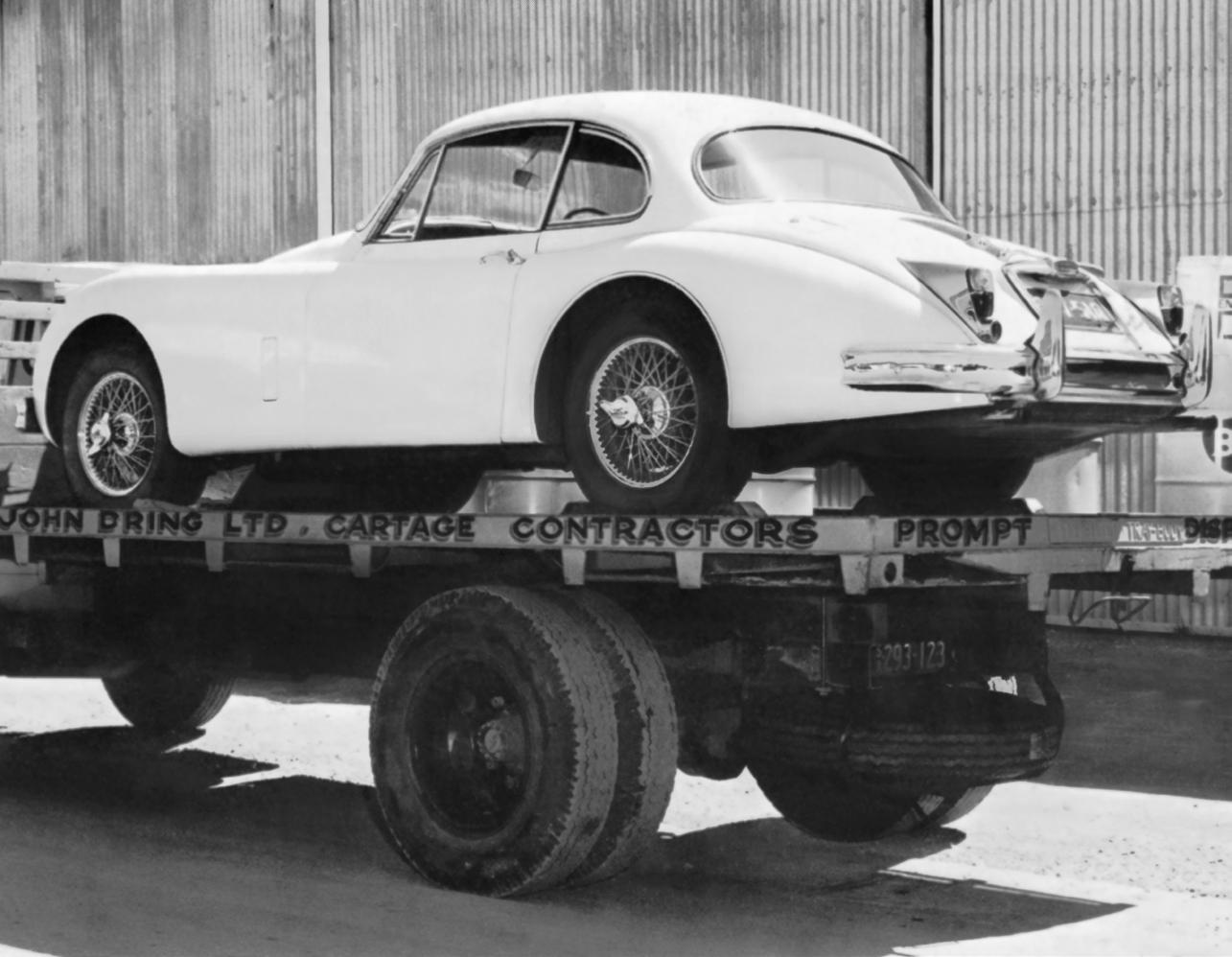

Another of just over one hundred RHD XK150S 3.8 litre Coupés were created. This one was trucked to salty Lake Eyre to assist on the Bluebird LSR attempt in the early 1960s. It made its way back to Melbourne where it is sprinted here at Calder by owner Duncan Fry. The salt affected it badly and the owner left very unhappy.

06

A prized XK150 automatic in a totally original low mileage state. It was rescued by Paradise Garage in Sydney and sold a few years ago.

01/02

Before they became highly sought after again. Both are XK150 DHCs, 01 is original but in need of restoration, while 02 was restored and modified by the lateLance McMahon.

03/04

Geoffrey Stevens chauffeurs Mario Andretti before the 1970 British GP. To keep DHC XLC 789 pristine he bought a rusty Coupé and created his unique Foxbat in 1975/76.

Shot by the lateJumbo Goddard, this image shows Ian McColl in his ex-Bill Leech 3.8 XK150s.

Ian was an early Club member, bought it in 1964 and kept it perfectly until his death in 2013 model the top speed was a very impressive 137mph and 0-62mph came up in 7.1 seconds.

Jaguar sent three XK150 running chassis to Bertone. They built their own interpretation of a car which might replace the XK150. It is thought three were built - two survive.

Driving The Xk150

If you seriously intend to look into the acquisition of an XK150 as your choice of classic car you need to know some important but fundamental things.

Firstly, today there are very few rusty wrecks out there. Most examples have either been restored, or they are sound original examples. Regardless, parts are not a problem be that electrical, mechanical, trim or panels so you don’t have to worry.

Reliability too is not an issue for any good XK150. Most parts had been used on previous Jaguars and any bugs eliminated.

What the XK150 has is style and charisma in loads. It is the Errol Flynn and Clark Gable suave sports car type, and you will feel very special when you are in it. It offers vast amounts of comfort and space, more than any previous XK, or even the E-Type which would replace it.

No matter the variation it also produces the best exhaust note of any Jaguar prior to the modern supercharged V8s, and aside from the usual ‘Moss’ non-synchromesh gearbox shift on first gear, which makes the gear change slower on that one, it is a joy to drive and is thoroughly modern even in today’s demanding urban traffic.

It is not perfect though, and you may want to make some changes to enhance the comfort for occupants.

The seats in the Coupé are broad and flat, so they offer no body support and result in sore bodies on a long trip. With no structural modification they can quickly be replaced by modern, but period-looking, bucket types which are superior.

Another issue is very heavy steering at parking speeds, and power steering will address that.

Finally, for the passenger in a RHD car, or driver in LHD, the floor can become unbearably hot. The reason? It is made from ply wood slotted into steel frames, and doesn’t provide enough protection from the hot exhaust pipes beneath on hot days especially. The wood too can be replaced with heat-repelling coated metal, again with no structural changes.

The rarest XK150 is the RHD Roadster, only two were sold new in Australia. Many have been imported from the U.S. and converted to RHD which does not affect the donor car’s value, but it will not match the higher price of any of the original 93 RHD Roadsters which are the most valuable, of course, in 3.8S specification. Only 24 XK150s were 3.8S’s. A mere two were standard 3.8s, and only 9882 XK150s of all types were built in three years so that they were always rare.

Would we recommend an XK150? The answer is a definite yes. With those simple changes you have the ideal fun classic sports car with all of the character a car with the XK150’s looks promises.

From NEW ZEALAND's original Jaguar distributor plus daimler

THIS IS A REMARKABLE book for many reasons, not the least being that four of the most honest and knowledgeable people on the subject have worked together to make it happen.

The first volume was published with the aid of the late-Danish Jaguar distributor and car collector Ole Sommer. His business has again backed this one.

The first came with a soft cover, this is a higher class presentation with a hard cover. It has an absorbing 417 pages of words and images on high quality paper.

Of course, it can never be up to date because cars change hands constantly, but what