8 minute read

WITNESSING HISTORY

LEAH MADDRIE

A FORTIETH ANNIVERSARY is a cause for celebration. Lincoln Center Theater’s (LCT’s) fortieth birthday occurs at a major turning point in the evolution of theaters in the United States. If you are reading this article during LCT’s 2024-2025 season, perhaps while attending a production at the Vivian Beaumont Theater complex, you are witnessing history.

Many founding or longtime artistic directors have passed the torch to a new generation of leaders, or will do so soon, and the industry at large is still recovering from the effects of a global pandemic. The audience demographic is in flux—or not, depending on which articles you read and which theater lobbies you frequent. The critical role of live performing arts, it is often said nowadays, has changed, as competing forms of entertainment and ways of engaging in culture become more popular, especially after the COVID-caused homebound period (for many) in 2020.

There has been much discussion in recent years about the ways that large, nationally known theaters like LCT could or should move ahead in this transition period. Before taking the next step, it is proper—and perhaps essential—to examine what has been accomplished so far and honor it. To provide context for the major shifts of today, it is helpful to review highlights of American theater history—and the history of the Vivian Beaumont Theater—in the mid-to late-twentieth century.

Once there was a time when the importance of the performing arts was not questioned. In fact, people with means, will, and energy vied enthusiastically to create a national theater for the United States of America, and this effort was seen as a vital endeavor. According to Jim O’Quinn’s June 16, 2015 article in American Theatre magazine, “Going National: How America’s Regional Theatre Movement Changed the Game” (a handy recap of the era that is also available in The Art of Governance, a collection of essays edited by Nancy Roche and Jaan Whitehead), non-profit theaters expanded across the country gradually. A few pioneering resident companies were established in the late 1940s and early 1950s, for instance, in Dallas (Margo Jones’ Theatre ’47 and its annual iterations) and Washington, DC (Arena Stage, founded by Zelda and Tom Fichandler and Edward Mangum in 1950).

A short time later, the blossoming of many theaters that still thrive today intensified, coinciding with the growth of the Ford Foundation’s arts grants program, led by W. McNeil Lowry. Arts creators, administrators, and philanthropists across the country sought to improve the quality of and access to American theater. “America had a hefty cultural inferiority complex in the late 1950s,” wrote John Kreidler in “Leverage Lost: The Nonprofit Arts in the Post-Ford Era,” a paper published in The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society in the summer of 1996. “With the emergence of America as the world’s post-war economic dynamo, there was an increasing mandate for comparable supremacy in the arts and culture.”

The founding of several more resident theaters in communities across the United States dovetailed with the quest to establish an official national theater. As stated in Helen Sheehy’s article 6 Dreams (which appears in this edition of LCT Review), in 1958, Vivian Beaumont Allen donated $3 million to build a home for a national theater on Lincoln Center’s campus. When she provided that gift, she was the vice president of the New York Chapter of the American National Theatre and Academy.

Between the opening of the space in 1965 and the establishment twenty years later of Lincoln Center Theater, the entity celebrating its 40-year history this season, other contenders were hailed prematurely as America’s long-sought prestigious national theater. In the 1960s, as Elia Kazan was starting the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center (which performed off-Broadway while its planned future home was being built), Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio Theater was established. Kazan and Strasberg had been colleagues in the Group Theatre, and Strasberg now headed the Actors Studio, the home of a technique called Method acting made famous by students including Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe.

But the Actors Studio Theater did not last long. Neither did the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center. After several companies and leaders failed to take hold in the Vivian Beaumont Theater, hope was nearly lost.

On July 17, 1977, after the departure of Joe Papp as the artistic leader in the space, Richard Eder wrote an article in The New York Times that asked, “The Vivian Beaumont Concept—Was It An Impossible Dream?” Frank Rich wrote a dire article on August 7, 1983, in the Times asking, “Can the Beaumont Become a Vital Company?” After lamenting the failure of so many enterprises in the building and bemoaning the years that—by that point—the space had remained vacant, he declared, “We need that company because the very future of our theater demands it.”

In the 1980s, a second wave of attempts to form a major American theater occurred. An October 5, 1983 Washington Post article, “Birth of a National Theater” by Richard L. Coe and David Richards, announced that “Beginning in the fall of 1984, Washington will be the home of a new national theater company to be housed at the Kennedy Center.” Kennedy Center Chairman Roger L. Stevens is quoted saying, “New York has a bad track record. They’ve tried many times to set up a national company and not been successful.”

Nevertheless, in June 1984 in New York City, Lincoln Center Theater (LCT), the theater as it is known today, was formed under the chairmanship of former New York City Mayor John Lindsay to produce work at the Beaumont Theater on Lincoln Center’s campus. At approximately the same time, director Peter Sellars was hired to lead the American National Theater (ANT) at the Kennedy Center. Ironically, that new theater was related to the American National Theatre of which Vivian Beaumont had been the New York Chapter Vice President.

ANT’s first official production, Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1, opened in March 1985, with Patti LuPone as Lady Percy. In New York that spring, Director Gregory Mosher and Executive Producer Bernard Gersten were hired to run Lincoln Center Theater. LCT’s first official show, a double bill of David Mamet plays, Prairie Du Chien and The Shawl, opened in December of 1985.

By late summer of 1986, ANT announced that Mr. Sellars was taking a leave of absence, and several ANT staff members were laid off, effectively ending that iteration of ANT. At LCT, The House of Blue Leaves by John Guare was running at the Beaumont Theater after succeeding well beyond expectations at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, and LCT was enjoying its first hit. A year later, ANT’s Lady Percy, Patti LuPone, starred in Anything Goes, another early LCT hit.

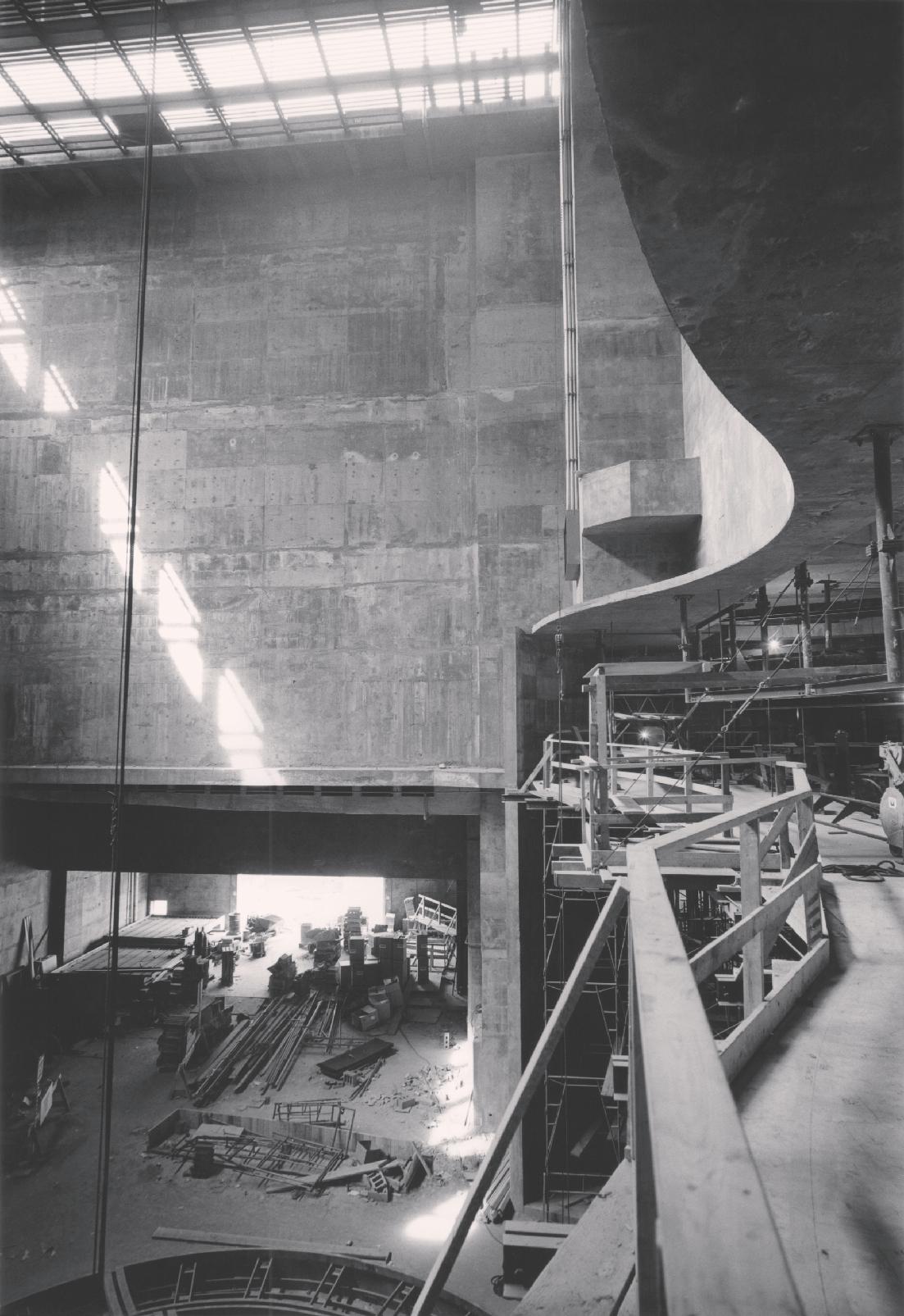

Forty years later, Lincoln Center Theater has combined the ideals of the resident theater movement and the stature of a national theater, producing work ranging from large-scale plays and musicals at the Beaumont, its Broadway house; to shows by established authors at the Newhouse, its midsize theater; to new works at the Claire Tow theater, a space with slightly over 100 seats built on top of the Vivian Beaumont. The Claire Tow opened in spring 2012 to house LCT’s most recent theater program, LCT3, which was established in 2008 to produce work by a new generation of artists for the next generation of audiences. LCT3 produced work at the Duke on 42nd Street while its home over the Beaumont was being built.

Who knows what will happen next? It is quite clear that the ground is shifting. (Literally. In March 2024, just before this piece was written, there was a small earthquake in New York City days before an eclipse.) Soon after the theater reopened after the worst of the pandemic in spring 2021, Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth was revived on the Beaumont stage with a reimagined script directed by Lincoln Center Resident Director Lileana Blain-Cruz. As the character Sabina says in that play, we are “Always beginning again. That’s all we do! Over and over again. Always beginning again.”

In that Richard Eder article in The New York Times about the difficulties of matching the Vivian Beaumont Theater with the right company to fill its stages, he said of the grand space, “Hope and expectation were built into it and will not leave it.”

Consider it an honor to bear witness to this era. Enjoy LCT’s 40th season, and take it all in.

Savor it. ▪

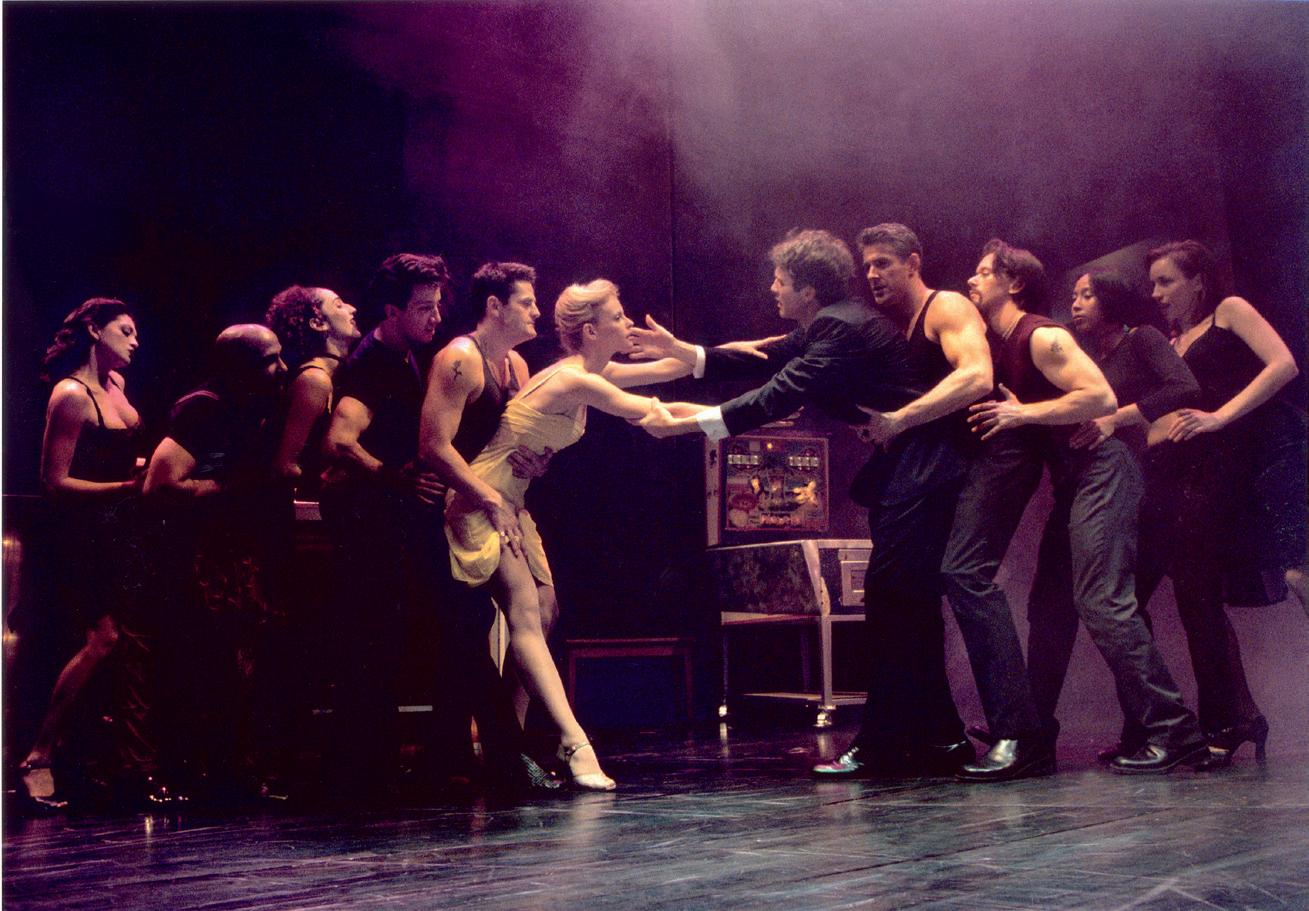

Header Photo: Deborah Yates, Boyd Gaine, with the cast of Contact. Copyright: Joan Marcus.