30 minute read

EXIT A HUMBLE MAN

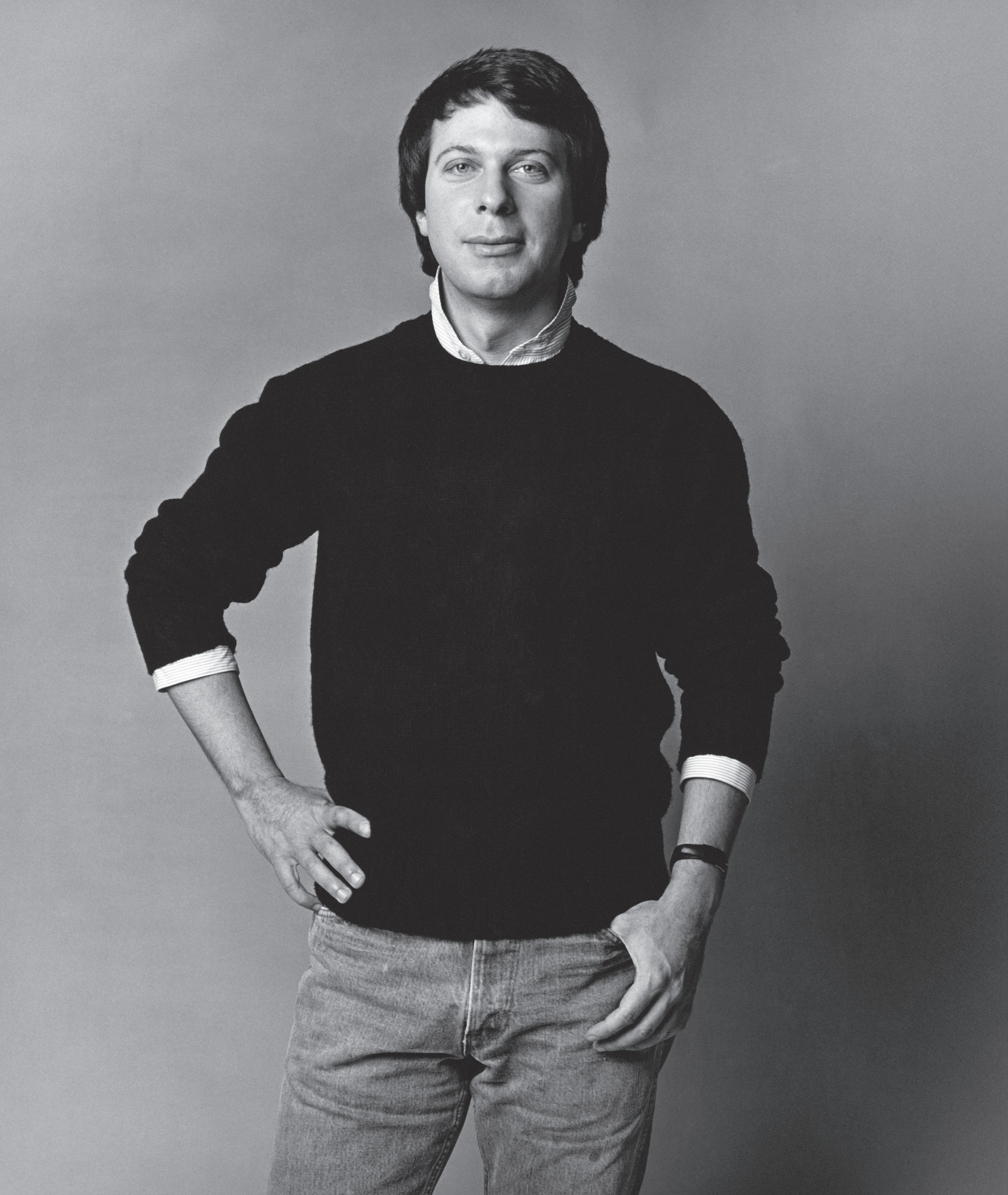

When one enters André Bishop’s office, there are a few things that immediately jump out. There are hundreds of books lining an entire long wall, and also stacked three or four deep on a coffee table, leaving no table top to be seen. There is a close-to-life-size painting of Polish actress Elżbieta Czyżewska, painted by John Wulp, which is surrounded by 86 coffee mugs, each on their own tidy wall hook. Photographs are everywhere, pinned on a cork-board or framed or just lovingly propped up on one of the aforementioned books. It is only after spending some time in this office that one starts to notice aknowledgements of his achievements tucked away: 15 Tony Awards stuffed into the overflowing bookcase, posters from every single Lincoln Center Theater show neatly stacked by the wall. More than one visitor has averted their gaze to the corner when speaking with André (even the kindliest theater legends can be intimidating), only to find themselves staring at the set model for Sunday in the Park with George—a reminder that it was André who commissioned and produced one of the earliest workshop productions. The office is André personified: smart, sentimental, brimming with love and loyalty, trimmed with keepsakes from one of the greatest theater careers in modern history.

In May of 2024, André sat down with Review Executive Editor Jenna Clark Embrey, on the sofa adjacent to the coffee mug-wall, to discuss his beginnings in the theater, his favorite moments at Lincoln Center Theater, and what he has learned as captain of the ship.

JENNA CLARK EMBREY: Let’s start at the very beginning—what was your first exposure to theater?

ANDRÉ BISHOP: As a kid, my parents tended to take me to musicals rather than plays, though I did see a lot of plays too. My parents believed in exposing me to the best plays in New York, not just children’s shows. At that time, New York theater was predominantly Broadway theater. I was always interested in the theater, even before I attended my first show. My aunt took me to a lot of my early theater experiences. Like many people, the first musical I saw was Peter Pan with Mary Martin on stage at the Winter Garden Theater. My aunt liked to sit in the first row of the theater— I hated it, but she loved it. So we were there in the first row of the orchestra for Peter Pan. And I remember there was one point when Peter Pan was flying, and I saw the stage lighting reflected on the wire. And suddenly I saw two things: I saw the magic of believing in something incredible, like how I believed that these people were flying, and then I also saw how it happened. I’ve always thought that the fact that I saw how it happened has dictated the course of my career, because I became interested not only in just the fantasy of it, but also in the mechanics of it. I choose to think that had we not sat in the front row, and had I not seen the light reflecting off the wire, then maybe the course of my life would have been completely different.

JCE: And that led you to acting, yes?

AB: Like all young people, I initially wanted to be an actor. I acted in school, wrote plays, directed them, and acted in them. I performed in plays like The School for Scandal and scenes from Tiny Alice. At Harvard, I was president of the Harvard Dramatic Club and performed in Much Ado About Nothing, Angel Street, and an experimental production of Three Sisters influenced by Grotowski. Christopher Durang was a few classes below me, and this production in some ways inspired his play Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike, particularly the use of “Here Comes the Sun” at the end. It was an infamous production, but even Frank Rich— who was also a student then—gave it a rave review in the Harvard Crimson.

JCE: Durang was one of the first writers you produced at Playwrights Horizons. How did you get your start there?

AB: I had quite a few jobs before joining Playwrights Horizons. I worked as a French tutor, and as a reader for the Book of the Month Club, where I recommended books for inclusion in the club. I was fired from that job when I gave a bad review to Doris Day’s memoir, which went on to be a huge success. I also worked for the record producer Ben Bagley, who produced the “Revisited” series that focused on Broadway artists such as Rodgers & Hart, Jerome Kern, and so on. I worked at the Delacorte Theater in the box office one summer, where I faced irate patrons who couldn’t get into Two Gentlemen of Verona. They threw their picnic baskets at me. Chicken bones rained down on me during those times. I could never figure out how to do what we used to call “rack the tickets” which was organizing them for pickup. I couldn’t find Joe Papp’s tickets because I had racked them under the wrong letter.

After my stint at the box office, I worked for the Department of Cultural Affairs, and a publishing house. Eventually, I found myself at Playwrights Horizons. A friend introduced me to Bob Moss, who was then leading the theater. We met, and I expressed my need for a home. Bob welcomed me, suggesting I come and hang out. There wasn’t any money involved, but I accepted the offer. Initially, I sharpened pencils and answered phones. Bob had plans for a theater in Queens, which would showcase old plays and help fund our productions of new works. It was during this time that I discovered a pile of unopened play submissions in Bob’s office. Seeing this, I asked if I could read and provide reports on them. Bob agreed, and he gave me the authority to assess and organize readings of plays, and eventually, he named me the literary manager.

In those days, literary managers weren’t commonplace, and I became close friends with Anne Cattaneo, who held a similar role at the Phoenix Theater. We were both navigating uncharted territory. As Playwrights Horizons grew, I became more involved in programming and operations. Eventually, Bob approached me, expressing his exhaustion with the theater’s financial struggles. He proposed either closing the theater or handing it over to me to run. Without hesitation, I accepted the latter. I became the artistic director and narrowed the theater’s focus to a select group of writers, including Albert Innaurato, Christopher Durang, Wendy Wasserstein, William Finn, and James Lapine. We experienced early successes with productions like March of the Falsettos, Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All For You, and The Dining Room.

JCE: Did you have a moment when you realized, hey, I’m really good at reading scripts?

AB: Yes, well, in a way. Because I read scripts as an actor, and therefore the plays that appealed to me most may not have always been structurally that sound, but I was very attracted to highly performable, highly theatrical material, and I think a lot of that had to do with my early acting. In the old days, you used to see actors sitting outside an audition room, kind of reading the script and mouthing the words, and that’s the way I used to read plays, and to some extent still do. I think that my training as an actor helped me, and I was an English major, I read a lot, I loved reading, I knew how to sort of write stuff, but I’ve always felt, in a way, both here and at Playwrights Horizons, I was more helpful to the director than I was to the playwright.

JCE: Why do you think that is?

AB: Because of that acting training, because I knew that I’d been on the stage, I knew it very well, I knew the mechanics, to go back to Peter Pan and the wire. I knew what was needed in the perform- ances of the actors, I think.

JCE: Did you ever want to direct?

AB: No. I did direct a bit at schools, but no, I never wanted to direct, because directors are just . . . they’re put upon by everyone, everyone has an opinion, and everyone wants to give their opinion as soon as possible and as loudly as possible, and I felt my nerves could not take that. I simply couldn’t remain calm in dealing with the onslaught of opinions that come your way as a director. So I never really wanted to direct, no.

JCE: I decided I didn’t want to be a director because it stressed me out to think about how to get things on and off the stage, that was the thing I couldn’t handle.

AB: Well there you go.

JCE: It has always been common— although it’s becoming somewhat less so—for directors to lead theaters. You’re one of the rare ones that comes from a literary management background. How did you go from running Playwrights Horizons to coming to Lincoln Center Theater?

AB: It wasn’t very complicated, as I recall, and it was certainly much less complicated than it would have been today, because this was in 1991.

I was at Playwrights Horizons for 15 years, five as literary manager, and 10 as the artistic director. I never thought of leaving, I was forty-something, I was still young, and it never occurred to me that I would leave. But I also never wanted to be there as a white-haired old man, locking up the door 40 years later either. But at that point in 1990 I wasn’t thinking of leaving. It never crossed my mind. I didn’t want to leave New York, because I was born here and raised here, and I never wanted to leave here.

Then one day I was at home in my apartment, and the phone rang. It was Bernard Gersten, who was then the executive producer of Lincoln Center Theater. I knew Bernie because I had worked in the Delacorte box office for the New York Shakespeare Festival in the summer of 1971, and I kept in touch with him, or he kept in touch with me, and I’d see him from time to time. I think that we all went on a trip to Russia at one point around 1989.

I was quite surprised that Bernie called because it was Saturday morning. He said, “I just want to pick your brain because Gregory is leaving Lincoln Center Theater, and we need to find someone soon, and I have a list of people, and I’d like your responses to this list.” He read me a list of about 10 or 12 names, and I would say, “well, you know, she’d be great,” or “he’d be good,” or whatever, and then finally there was this pause. Bernie was at the end of the list, and he said, “What would you say about André Bishop?”

I was completely taken aback and I couldn’t think of anything to say, so I said, “Well, he might be a sort of interesting choice?” With a big question mark. Then we talked a little bit further, and then that was it. And by that point I had gotten interested. I had one meeting with Bernie, a sort of secret meeting early in the Beaumont, and that was that, I was offered the job.

I never thought I would ever leave Playwrights Horizons quickly, because I loved Playwrights Horizons, I helped build it with Bob Moss and expand it, and it was a beloved place to me, and the people who worked there and the writers we worked with were beloved figures in my life. But I talked to one or two of my friends asking for advice, Wendy Wasserstein being one and Gerald Gutierrez being another, both of them no longer living, alas. They urged me to do it, and then I just thought, “well, okay.” I had always had a vision that I wanted to do more in the theater than just only produce new American plays, which is what Playwrights Horizons does, and musicals. I really wanted to do classic plays too, and classic musicals, that was very important to me. And although I had never wanted to leave Playwrights Horizons, I also thought that maybe I’d never get a chance like this again, and so I went to Lincoln Center Theater.

JCE: What was programming your first season at Lincoln Center Theater like?

AB: The trick to it was, they wanted me to come not at the end of the season, but in the middle of the season, because I think nothing had been programmed for beyond January. Six Degrees of Separation was still running, but I had to produce something quickly. For the Mitzi I decided to bring Jon Robin Baitz’s The Substance of Fire with Dan Sullivan directing.

And then the first new show for the Beaumont was Robert E. Sherwood’s Abe Lincoln in Illinois. I wanted to open my tenure with a show that would really show the Beaumont off. That was a huge, old-fashioned play in three acts with lots of different scenic scenes and a train that moved at the end towards the back of the Beaumont. Gerry Gutierrez was the perfect director to direct it, and in those days we were allowed to use Juilliard students as the crowd at the end of when Lincoln goes off to Washington to his inauguration. I just wanted to show the play off, and Sam Waterston played the lead, and was wonderful. Gerry was not only a good friend, but he was quite savvy about thrust stages and how to use them, something that I was not, so he was the ideal director.

JCE: Before you arrived here, what was the public perception of the Beaumont like?

AB: The Beaumont had many administrations, starting with Elia Kazan and Robert Whitehead, then Jules Irving and Herbert Blau, Richmond Crinkley, Joe Papp—none of these administrations lasted exceedingly long. The Beaumont went dark for a period.

There was a lot of public discussion about what to do with this dark building. There were many reasons it hadn’t worked, one of which was the obvious one: unlike all the other constituents up here who had existed prior to Lincoln Center—the City Ballet, the Metropolitan Opera, the City Opera, the New York Philharmonic, etc.—there was no Lincoln Center theater company. They built the building and then tried to find a company as opposed to having the company and building the building for them. That was the mistake, I think, made originally, and I think that’s why it became a matter of great concern to the City of New York because this place had been dark and empty.

It was during Richmond Crinkley’s era that the Board met a lot and was planning to convert the Beaumont into a proscenium house, because the feeling was that the theater didn’t work, couldn’t work, would never work.

However, Gregory Mosher and Bernie came in and made it work for the first time. They didn’t have a lot of money to begin with, but they were very smart.

JCE: Are there any shows at Lincoln Center that you were a little worried about how they would work, architecturally speaking, that ended up working beautifully and surprising you in that way?

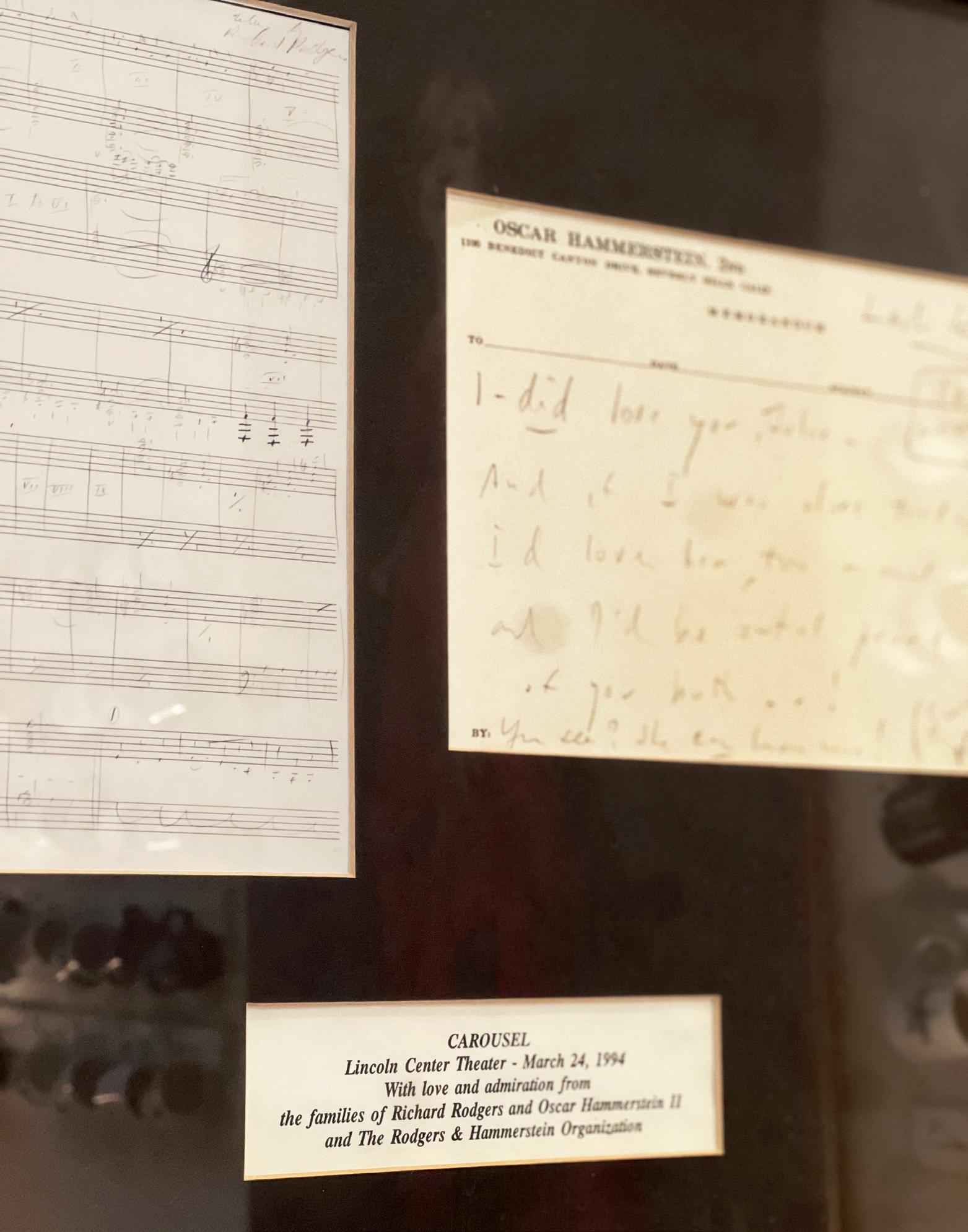

AB: Well, I was curious as to how the big musicals would show up, because big classic musicals such as Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I, and My Fair Lady are not usually done in thrust theaters. One wonderful thing that happened was that the Beaumont had been built to convert itself into a proscenium house as well as a thrust, and there was all this mechanics underneath the stage of the Beaumont: elevators and lifts that could, at the push of a button, change the configuration from thrust to proscenium. Well, that never worked. I think they tried it once and then all the machinery got stuck and they just left it there. And I can’t remember who thought of it, it was probably Bernie, thought, “Why don’t we clear out all this junk, all this metal and stuff under the stage and make an orchestra pit out of it?” So we did!

JCE: Is that why we don’t have a permanent deck in the Beaumont?

AB: Yes, partly. And also, the height of decks and the width of decks and the curve of decks all change according to the design.

I was concerned about that, and we solved it very well in Carousel, which was a wonderful production that came from the National Theatre in London, though we had an American cast. We didn’t do very many living room plays in the Beaumont, but we started all the living room plays, such as The Sisters Rosensweig, in the Mitzi. The Mitzi is easier to handle in a way because it’s smaller, but it is harder be cause of the limited space, no depth under the stage at all, and limited wing space compared to the Beaumont. So I was concerned about what The Sisters Rosensweig would look like in the Beaumont, we had John Lee Beatty, who is a master designer, and we figured it out.

JCE: What kind of advice do you give directors when they’re working in the Mitzi and the Beaumont for the first time?

AB: Well, the advice I give, especially in the Beaumont, is not to be afraid of the space. To realize that going left and going right is effective, but going up and going down is even more effective, and not to be afraid about going upstage. Figuring out how to stage the play that the sight lines are good for all seats. Bartlett Sher always says this: one of the things you have to do in a thrust stage, whether it’s the Beaumont or the Mitzi, is you have to keep the actors moving more than you would in a proscenium space. And you have to justify those moves, they can’t just be “oh, the actor decides to wander around.” And that’s more difficult, because why does the actor make a tour of the downstage area and end up back on the other side of the stage? How can you motivate that psychologically or dramatically that it isn’t just an actor wandering about so both sides of the thrust can see him, so that the audience can see him? I give advice like that, and I give very big advice about the need to push it out there vocally.

JCE: I feel like our theaters demand a certain high level of understanding of the offstage architecture of the set—what rooms are where, even when you can’t see them—because there are so many more entrances and exits than in a proscenium.

AB: Yes! We have vomitoriums here that we don’t always use, but we use them more often than we don’t. And you can make downstage exits off the deck, you can go off the stage, which on most Broadway stages, unless they put steps and you go into the house, you can’t do. And voms are very effective, because you’ve got four to six entrances and exits as opposed to four or two.

JCE: If you had a magic wand or a time machine, what are the shows from your time at Lincoln Center that you would like to go back and watch again?

AB: Well, many of them, but I guess South Pacific would be one, that is my favorite musical.

JCE: It’s my favorite musical too!

AB: Oh, is it?

JCE: Yes.

AB: Well, you know, we did a superb production of it. People always think we do these old musicals to make money, and nothing could be further from the truth. We do these old musicals because I love old musicals. But also, everyone told me not to do South Pacific.

JCE: Really? Why?

AB: Oh, “that old show” and “the book is creaky” and this and that and the other thing. And I felt that that wasn’t true. And I knew that Bart could tell a story, and South Pacific is a lot of story. That’s what won us the rights when I went to Ted Chapin, who was head of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization. So I would like to see that again. I was happy when we did that.

I would want to go back and see The Coast of Utopia again because I didn’t see it enough times, really. And those marathon days . . . we thought they would be disasters. They were the biggest sellers that we had. The production was magical. Oh, there’s many shows with many great performances. But I do have one regret about my time here.

JCE: What’s that?

AB: The one regret I have leaving Lincoln Center Theater is that I had always wanted to start a repertory company here. And I talked about it very heavily with director Gerald Gutierrez when he was alive, and then with Jack O’Brien. Those two men came with great knowledge of repertory, Gerry with The Acting Company and Jack with the APA Repertory Company.

Gerry and I had this idea because repertory would be very difficult to get first rate actors to commit to that length of time. So we thought we would try and have a company that would gather together for a year every three years. So if this actor or that actor would commit to one season every three years, we might have a chance of getting a first rate company and to do a bunch of plays in the Mitzi and the Beaumont in rep. But it proved to be difficult and expensive that I didn’t push hard enough for it. I don’t know if it would have ever happened, but I wanted to restore the Repertory Company of Lincoln Center as it had been called, I wanted to do that and I never did. The trade-off was I pushed very hard for LCT3 and for a new theater, a third theater, and that happened. I guess you can’t get everything.

JCE: When did the idea of LCT3 first come to you?

AB: Well, I’d forgotten this, but I looked it up a couple of years ago and I realized that in my first contract, the very first contract I had here in 1991, one of the things I asked for was a black box theater—a third theater to produce young writers in. And this was a very short contract. I’m sure these days they are pages and pages long, but mine was about a page and a half. And the board said they would use their best efforts to see about building this black box theater.

Then I got busy. I had a lot to learn when I came here. There was a lot I did not know and had it not been for Bernie, I don’t know how I would have survived because I came from a small proscenium theater to a huge thrust stage. I was ready for it and yet I wasn’t ready for it. Anyway, I just forgot about the black box theater thing for years. I was too busy doing this and that and discovering this and we were doing that. And then there was a bad year—I think Wendy had just died—and one day, I was sitting on this sofa, where you’re sitting now, and I was thinking about how we had lost this family of artists that had either been here, or I had brought here. Either we had lost them to television, or to illness, or to death. I was trying to plan the rest of the season and I couldn’t think of anything to do because my colleagues, the pillars of my artistic life, were no longer here. That’s when I thought, “well, how do we bring more artists in? How do we do it?”

We had a very robust reading program and workshop program, there was no need to expand that, especially since every theater in the world does readings now. One thing I strongly believe is that what writers really need are productions. And at that point I’d forgotten about my contract demand for a black box theater, and I realized that I didn’t actually want a black box. I wanted a small professional theater where plays would be produced and we would get good actors, perform for audiences, charge money, and be reviewed. My thought was that even- tually the writers and directors and designers from this small theater would filter into the Mitzi and the Beaumont. We’d find a new generation of artistic pillars. So we talked and talked about it, and the Board supported the idea, and in about 2008 we started this program with performances at the Duke Theater down on 42nd Street. The Board felt wisely, “let’s see if the program works before we start building anything.” And then it did work.

We started planning for a new theater, and we knew it had to be here, on campus, not downtown or far away. We wanted all of our artists to be together in one place. But the question became, “where?” Because this building, though it’s huge, didn’t have a lot of space to give. Then someone, I don’t remember who, had the brilliant idea of building on the roof. But the roof was not built to be built on. Thankfully, we found Hugh Hardy and his firm, The Architect, and we started raising money and having endless meetings about what would become known as LCT3. We had to persuade a lot of people, the community board and so on. But Hugh was an immense help because he had actually worked on the initial building of the theater! He had been the go-between between Jo Mielziner, the famous set designer who designed the theater’s interior, and Eero Saarinen, who designed the exterior. And Saarinen and Mielziner hated each other, so Hugh became sort of the mollifier and translator and peacekeeper. So with him designing LCT3, he was very comforting to all the people who were worrying, “will this work? Will this be okay?” We raised the money, we built the theater, and in 2012, we opened the Claire Tow.

JCE: What makes something a Lincoln Center Theater show?

AB: Well, I don’t think about it that much. I think about it because I have to, architecturally. I have to think about whether this play is suitable for a thrust stage. To pretend that that doesn’t come into anyone’s thinking is wrong, because you have to think about it. There are certain plays that don’t work that well in thrust, and certain plays that work better in thrust, or can be more effective in thrust, because the audience isn’t as far away as they are in proscenium houses, or big proscenium houses. I’ve always believed—even though it’s no longer considered proper, I suppose, or fashionable—that picking plays or producing plays is simply the intelligent exercise of one’s own taste. I’ve always felt if I liked something and responded to it emotionally, or intellectually, or both, that others, if we did it well, would feel the same way.

Now, that obviously has not always been true, either because I was wrong, or the production wasn’t good enough, or whatever. And it’s only been in the past 10 years that I’ve begun to think more clearly about social responsibility, plays that can inform your feelings about the world a little more.

In my early days at Playwrights Horizons, and here, what attracted me was the idiosyncrasy and the distinctiveness of the author and the author’s language. That’s what I responded to. I think my tastes have broadened since, in all the years I’ve been here, and I’m interested in a wider variety of plays than I used to be, I think. I think I’ve grown in my job.

JCE: Looking back over all these years of being an artistic director, what has surprised you?

AB: Well, what surprised me was that even after many years, I still felt I had much to learn. Things would happen, good things or bad things, that even after many years of working, I was completely unprepared for. That was one thing that has really stuck with me. I have realized that you never have all the answers, either intellectually or emotionally, and that has surprised me.

Another thing that has surprised me is that the whole climate of the New York Theater has changed. It went from nonprofit theaters being an alternative to the commercial theater—and those words, “alternative to the commercial theater,” were in the initial mission statement of Playwrights Horizons, because it said that Playwrights Horizons exists for the development and production of new American work by playwrights, composers, and lyricists, and for the production of their work as an alternative to the commercial theater. Well, that, of course, is completely gone now, and many nonprofit theaters are used as sounding boards for commercial productions and take commercial money and enhancement money, and unfortunately, many people in the theater and on the outside of the theater think success has to do with how many plays move to Broadway. I was surprised that that has happened so quickly in my lifetime, because when I came in and when we started Playwrights Horizons, you didn’t do that. You would lose your nonprofit status, or you would get into trouble in some way or another. That has very quickly changed, and it’s understandable, because there has never been, despite good years and bad years, enough money.

This country does not subsidize the arts. The government does not subsidize the arts. In Europe it’s less than it used to be, but still in Germany, England, Italy, and France, there is a great deal of subsidy. Now we are all, as nonprofit institutions, not just theaters, obsessed with money, the bottom line, and “how we can make it through the year?” This is not a good thing. It doesn’t help you. There are various funding sources I know who think that poverty keeps you on your toes. I don’t believe that for one second if you’re a responsible human being, and I think that’s been the biggest surprise to me.

I understand why many theaters are interested in commercial success, because it gives them an income, but that makes me very sad, and it makes me redouble my efforts. I went to Washington with a bunch of people and testified several times to continue the NEA and continue subsidy for the arts, and that was in the eighties. I thought there would eventually be more subsidies. The fact that foundations and corporations were turning away from the arts as they are now, I didn’t see that coming.

JCE: Can you talk a little bit about Bernie?

AB: Well, Bernie was . . . they don’t make Bernies anymore. They haven’t for quite a while.

Bernie was a manager with flair, and he wasn’t a numbers person. That was what was great about him as a manager. Bernie’s idea of management was, “We are not here to make money or save money. We are here to spend money.” I remember coming up from Playwrights Horizons where we had to watch every penny, and there was this incredible man, head of management, whose idea of a good time was to spend money even when we didn’t have it, and to dare to do things. And Bernie had the great advantage of being older than we were. He had worked at the Shakespeare Festival, he had produced on Broadway, and he had worked here in the Beaumont when Joe Papp and he were running it for a brief amount of time. And Bernie loved the theater, he loved putting on a show, that’s what he was interested in. Bernie loved hits, and he was never happier than when we had full houses and audiences pouring into all the theaters.

He was an optimist. He always used to say that I was Apollonian and he was Dionysian. And there was truth in that. Because he was expansive and lifeloving and wine-loving and all of that. And I was more serious, troubled, and worried. But we united on certain things. One was we both wanted to create a warm and respectful environment for artists in which to work. I came here from that philosophy, which we very much had at Playwrights Horizons. And he had that himself because he was a warm person and cared about people. If you didn’t know what to do, you could go to Bernie.

And Bernie had this wonderful way of communicating with the Board. Whenever times were tough, he would haul out a chart showing our ups and downs and ups and downs financially, and they used to call it Gerstenomics. What Bernie Gersten had, among many qualities, was a love of the theater and an excitement for it. And I appreciated him a lot when we were working together because we worked together for many years. He was very deferential to me as the artistic director. He never interfered with my decisions or anything like that. But in the past five or six years, if I appreciated him then, I really appreciate him now. I realize with every passing day here how important he was to all of us and to me. And I’ve never met anyone like him again. They just. . . as I said earlier, they don’t make people like him anymore.

JCE: What words of wisdom might you have for the next person who leads this theater?

AB: I would say what pretty much anyone in my position would say, which is: honor the past, be grateful for the present, and work like hell for the future.

I hope whoever replaces me will honor the basic values that this theater has always espoused, which is on a day-to-day, workaday level, about creating a warm and supportive home for artists. I would hope that person would continue my obsession with new American plays and musicals, and I hope that person would then take this theater into new dimensions that I didn’t do. I hope that the theater doesn’t change, but I also hope it does. I think that’s healthy. Change is a good thing because change creates opportunities, and opportunities create artists.

Header Photo: The New York Times article, "Enter a Humble Man", by David Richards, September 13, 1992. PARS International Corp.