15 minute read

6 Dreams

We all need to know where we come from, and in this regard, theaters are no different than people. The history of what we now know as Lincoln Center Theater is one of the more colorful tales among artistic institutions. If looking at the glass as half-empty, one might describe the early administrations of Lincoln Center Theater as false starts, but as HELEN SHEEHY so incisively describes in this 2010 essay, the first few decades were crucial building blocks—as Antonio says in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, “What’s past is prologue.”

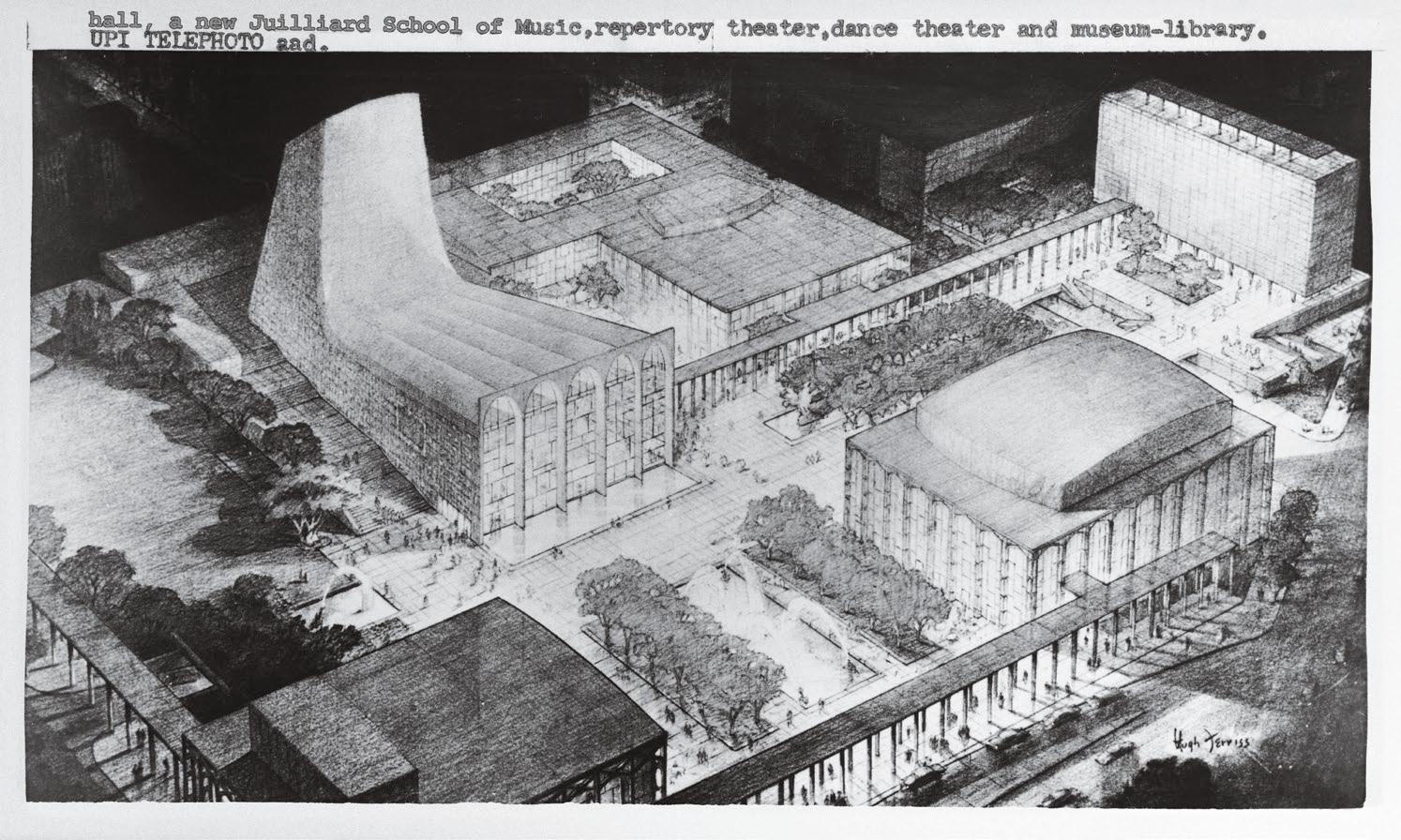

IN 1958, VIVIAN BEAUMONT ALLEN gave $3 million to Lincoln Center, hoping to build a national theater “comparable in distinction and achievement to the Comédie-Francaise.” To dream the new theater into existence, a theater that would stand on equal terms with the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and the New York City Ballet, the Lincoln Center Board looked a few blocks south and chose two distinguished and respected Broadway veterans, the director Elia Kazan and the producer Robert Whitehead.

Elia Kazan, then fifty-one, who compared himself to a black snake because he’d shed his skin so many times, had co-founded the Group Theatre and the Actors Studio, and on Broadway had directed the plays of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. Robert Whitehead, handsome and dapper, with a mustache that made him look like a riverboat gambler according to Tennessee Williams, was admired for the artistic merit of his commercial productions, including Medea, starring Judith Anderson and John Gielgud, and Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding, introducing Julie Harris and the blues singer Ethel Waters.

The team of Kazan and Whitehead wanted, they said, “to make the theater necessary again as the great theaters in eras past were necessary.” They planned to bring together the best theater artists in the country and “make art, not business.” Whitehead warned, “It may take a lifetime.” The news was greeted with hyperbolic praise and anticipation. After all, the theater at Lincoln Center would be the first new theater built in New York since the Ethel Barrymore in 1928, and the first attempt to create a new repertory company since Eva Le Galliene’s Civic Repertory Theatre, which flourished from 1926 until it closed seven years later during the Depression. The New York Times proclaimed, “This is the first seismic tremor in what may prove to be a great earthquake in the American theater.”

The opening of the theater (in a temporary structure downtown, because the Vivian Beaumont Theater was still just a huge hole in the ground) in January 1964 was a cataclysm, quickly followed by chaos and devastation. For the inaugural production, Kazan directed Arthur Miller’s memory play, After the Fall, with characters based on the playwright, Marilyn Monroe (although Miller denied it), and an informer modeled on Kazan. The critical reception was merciless and vitriolic, although audiences, lured by voyeurism and the combined star power of everyone involved, sent ticket sales soaring.

After one season in the temporary theater, which included productions of Miller’s Incident at Vichy and The Changeling, Kazan’s attempt at directing Jacobean tragedy, the impatient board, prodded by a hostile press, forced the men to leave. Although Whitehead continued to produce serious theater on Broadway, Kazan never staged another play. “I was not the man to solve this problem,” he said.

If Kazan couldn’t solve the problem, who could? Never mind that it had taken England more than a century to create its national theater— the board members wanted immediate results, so they searched for new dreamers. This time they traveled three thousand miles west and found perhaps the unlikeliest candidates in American theater—Herbert Blau and Jules Irving, co-founders of the Actor’s Workshop in San Francisco.

Blau, a former professor, had just published The Impossible Theater, A Manifesto. A theater revolutionary, Blau wrote, “There are times when, confronted with the despicable behavior of people in the American theater, I feel like the lunatic Lear on the heath, wanting to kill, kill, kill. . . .” At the Actor’s Workshop, Blau and Irving had directed and produced more new American plays than any other regional theater and introduced their audiences to avant-garde drama, including Bertolt Brecht, Jean Genet, and Harold Pinter.

In 1957, they presented Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at San Quentin State Prison. “I don’t want to be doing Mary, Mary when the bomb drops,” Irving said.

When they moved to Lincoln Center, bringing many members of their company with them, Blau and Irving promised that “ideologically we shall remain . . . three thousand miles from Broadway and what it represents.” Once again, there was great fanfare in the press, and enormous excitement. Regional-theater historian Joseph Ziegler observed that Blau and Irving’s move to New York was a “major turning point of the regional-theater revolution because it marked the first time that the central powers turned to the periphery for help.”

“I wasn’t long at Lincoln Center,” Blau wrote later, “before I felt rather like Captain Ahab on the third day of the hunt.” After one season of classical plays and an inability to surmount the technical and acoustical problems of the white whale of the Beaumont stage, Blau left.

Jules Irving, a charming former actor and a self-taught financial wizard, stayed on for six more years, and achieved many successes on the small jewel of the Forum Theater’s stage with productions of Pinter, Beckett, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt. When the Forum’s season was canceled because of insufficient funds, Irving resigned in protest. “Our dramatic heritage is being strangled by indifference,” he said.

Into the vacuum stepped Joseph Papp, then fifty-two, the self-made son of a Polish immigrant and a man who dominated New York theater, moving easily between a summer season of Shakespeare in Central Park and his Public Theater downtown, which housed four theaters, as well as productions on Broadway and television. With Bernard Gersten, his brilliant producing partner, Papp was successful both in the institutional, nonprofit world and in the commercial theater. The board wooed him, and the marriage settlement included a change of name. The Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center would now be called the New York Shakespeare Festival at Lincoln Center. “If Papp did not exist,” Mel Gussow wrote, “some playwright would have to invent him.”

During his first two seasons, Papp brought new playwrights like David Rabe and Miguel Piñero to the Beaumont’s stage. Almost all of the plays he produced were controversial, filled with sex and violence; this enraged the theater subscribers, whom Papp privately referred to as “the Viennese.”

The following season, Papp changed his policy and produced a season of classics, which inspired another wave of protest that he had shed his principles. In an effort to “create a bridge between the avant-garde theater and the conventional theater,” Papp mated experimental directors with classics, producing Richard Foreman’s version of The Threepenny Opera and Andréi Serban’s production of The Cherry Orchard. Suddenly, just as audiences were beginning to respond to his experiments, Papp resigned, saying that he felt “trapped in an institutional structure both artistically and fiscally.”

During Papp’s first season, the writer Patricia Bosworth followed him around for days. In all that time she wrote, “I never saw anyone cross Papp publicly—except one . . . very fragile-looking woman.” It was at the ceremony renaming the Forum the Mitzi E. Newhouse. “Papp sprawled on the stage,” Bosworth wrote, “puffing on a huge cigar. Mrs. Newhouse attempted to speak but seemed to be fighting for breath. Pausing, she waved her tiny, jeweled hands in the air and cried: ‘Joe, please? No cigar smoke in my theater.’ Papp quickly stubbed out his cigar.”

To replace the colorful outsized Papp, the board chose Richmond Crinkley, an amiable Southerner, who had served as director of programs at the Folger Shakespeare Library and also as Roger Stevens’ assistant at the Kennedy Center. In 1979 just after he took the Lincoln Center position, Crinkley moved his production of The Elephant Man to Broadway, where it won a Tony for Best Play.

Crinkley’s dream for the theater at Lincoln Center emphasized “our American and English-language artistic heritage.” He named a five-member directorate, made up of Woody Allen, Sarah Caldwell, Liviu Ciulei, Robin Phillips, and Ellis Rabb to help him run the theater. In 1980-81, he produced a three-play season of Raab’s The Philadelphia Story; Allen’s The Floating Light Bulb, directed by Ulu Grosbard; and Sarah Caldwell’s Macbeth. None of the productions were successful, either critically or at the box office. The theater remained closed, while Crinkley and the board pondered changing the Beaumont into a proscenium theater. The proposal made sense to Crinkley, since most American classic plays had been written for the proscenium, and to save money he wanted to share productions with the Kennedy Center, which had a proscenium stage. When the board lost a $4 million foundation grant to rebuild the Beaumont with a proscenium arch, Walter Kerr pointed out that “proscenium stages don’t establish brilliant acting companies, they don’t go out and find talented directors, and they don’t, of course, write plays. They just stand there.”

It took Peter Brook’s luminous staging of Carmen (as well as a subtle reconfiguring of the space that had been intermittently shuttered since 1977) in 1984 to prove that the Beaumont could work. Thirty-four-year-old Gregory Mosher, the artistic director of the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, saw that production and realized that Brook had found the theater’s “sweet spot.” In July 1985, a reorganized board, led by former New York City Mayor John Lindsay, gave Gregory Mosher and Bernard Gersten, as executive producer, the challenge of relighting a theater that had been dark for most of the last eight years.

The year before, Mosher had directed David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross on Broadway and was no stranger to New York theater. Still, he came to his new job with some apprehension, packing only two suitcases, not expecting to stay long. Almost immediately, he made significant changes. Lincoln Center Theater Company became Lincoln Center Theater. He’d realized from Papp’s tenure that Papp had been boxed in by the subscription season. “Subscription is the only system where you close your hits and run your flops,” Mosher said, and he inaugurated a membership system instead. “Good Plays, Popular Prices” became the theater’s motto. And, while previous artistic directors talked endlessly to the press about their plans, Mosher refused to discuss his vision. “What are you about?” reporters would ask, and he said, “Come to the plays and then you tell me.” Almost every day for six years, Mosher said to the staff, “We are not our press releases, our reviews, our balance sheets, our interviews, our annual reports, or our awards. We are what happens at 8.”

The theater’s first big hit was John Guare’s The House of Blue Leaves, which began at the Newhouse and moved upstairs to the Beaumont. More hits followed, including Anything Goes, Sarafina!, Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow with Madonna on Broadway, Thornton Wilder’s Our Town with Spalding Gray as the Stage Manager, Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation, and a number of other new and old plays, some of which were flops.

In 1991, Mosher quit. “I was very tired,” he recalled. “I had taken two, two-week vacations between 1974 and 1991.” He’s modest about the success that eluded, he believed, much greater directors. “Everybody had been trying to get the lid off the pickle jar for years,” he said, “and the guy who finally does it doesn’t deserve the credit.”

For the sixth time, the theater needed a dreamer. “We knew we had to find someone very special,” said board member Linda LeRoy Janklow. Bernard Gersten put together a list that included André Bishop, the artistic director of Playwrights Horizons, a small Off-Broadway theater devoted to new American works and as different from Lincoln Center Theater as could be.

A shy, scholarly man with a self-effacing manner that masks a formidable will, Bishop at the time was the golden boy of the New York nonprofit theater, having put a distinct stamp on the work of Playwrights Horizons and, in the process, produced a number of extraordinarily successful new shows, including three Pulitzer Prize winners: The Heidi Chronicles, Driving Miss Daisy, and Sunday in the Park with George.

“Leaving Playwrights Horizons was like leaving my youth behind,” Bishop recalled. “Lincoln Center Theater was everything I knew nothing about—it was big, it was uptown, it was a marble palace with two difficult thrust stages. Yet I knew I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life doing new plays in a very small theater, albeit a theater I loved with all my heart. I think I had unconsciously been looking for a bigger canvas. I wanted to do Shakespeare and the classics and large-scale musical work. I also knew that if I didn’t take the opportunity another one might never come along again.”

Knowing that he was nervous about the change, the director Gerald Gutierrez, a friend of Bishop’s counseled him. “Darling, don’t worry about a thing. Just pretend you’ve come into an inheritance and you’re moving uptown into a very large and splendid apartment.” Bishop took his advice and the advice of another friend, Wendy Wasserstein (“Do it, André—you have to do it”), and came to Lincoln Center Theater with happiness and great trepidation. He need not have worried.

For eighteen years, things have worked out for André Bishop. But despite success with a number of new plays and musicals, including The Sisters Rosensweig and Contact, to name two, Bishop feels that he has not been as effective in the new work arena as he should have been, given his background at Playwrights Horizons. “We need to produce more new plays and spend more time working with younger generations of directors. This is why we have started a new program—LCT3—that will exclusively produce the work of new playwrights with new directors and designers and a very low ticket price. We hope to build this third theater, to be named the Claire Tow Theater after the wife of one of our board members, on the roof of the Beaumont. Meanwhile, to get things started, we are renting outside space,” he says. Ironically, his greatest achievement has been the very thing he had no knowledge or experience of when he arrived at Lincoln Center: the constant and effective use of the Beaumont Theater. With the help of a group of first-rate directors and designers who weren’t afraid of the space—in fact, they reveled in it—and a major renovation that solved the acoustic and seating problems, LCT, under Bishop’s direction, presented many extraordinary productions in the Beaumont—including Carousel, The Coast of Utopia, Henry IV, and Rodgers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific—to popular and critical acclaim.

Years earlier, in their first subscription brochure, Blau and Irving dreamed of a theater at Lincoln Center that would be a “crossroads, a meeting hall, a shrine, a playground, and a battleground . . . a place of wonder and confrontation where the prophetic soul of the world, in an age of revolutions, may do its dreaming on things to come.” Bishop says, “Well, those were fancy words, but I’m not sure what they mean. I believe in dreaming in private and then letting people come and see the results. I don’t know what the future will bring,” he adds, but he continues to dream. ▪

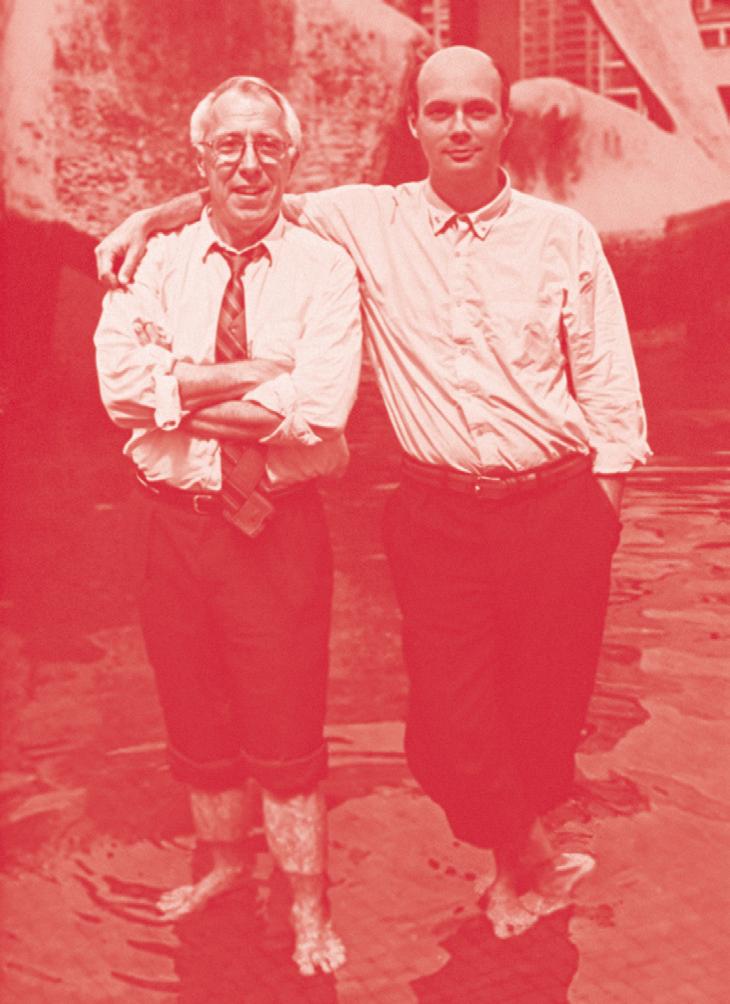

Portrait of members of the Lincoln Center Repertory Theater as they pose, standing in a reflecting pool (later named the Paul Milstein Pool) at Lincoln Center, NY, New York, October 13, 1965. Among those pictured is American actor Stacy Keach. They stand in front of Henry Moore’s ‘Reclining Figure.’ Behind them is the Metropolitan Opera House and, at extreme right, the overhang of the Vivian Beaumont Theater (which would open to the public eight days later).

Header Photo: Arthur Miller and Elia Kazan and entire cast and creative team in rehearsal for the stage production After the Fall, 1964. Photo by Martha Swope. Courtesy of the Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections