2024 marks the 130th anniversary of the train coming to Barry’s Bay.

The StationKeepers MV, who now operate the railway museum located in the train station located in the heart of Barry’s Bay, are marking this huge occasion with a celebration on August 31, 2024 at the Train station and Water Tower Park

The StationKeepers will unveil a new, hand-built, wooden children's play structure in Water Tower Park. The design resembles an old locomotive and several rail cars.

The Valley Gazette wanted to mark the anniversary with a special section dedicated to the rail history of the area. Inside you'll find history on the pre-rail days of logging and history of the trains that passed through town.

Inside, you'll find stories about the major players in launching rail service, memories of people who rode and worked on the line and how the station has evolved over its 130 years.

We hope that you enjoy this commemorative publication.

TheValleyGazette

Published by Lavigne Media

Publisher

Michel Lavigne

Production

Derek Layman

Editorial

Robert Fisher

Toni Lavigne-Conway

Contributors

David Villeneuve

Victoria Cybulskie-Blank

Arthur Rumleskie

John Mintha

Barry Conway

Theresa Prince

Joanne Olsen

David McBride

Robert and Cathie Corrigan

Joseph and Peggy Rumleskie

Ralph Pecoskie

Don Derraugh

John Bozak

Jacques S Leroux

StationKeepers MV, a not for profit group of volunteers, is pleased and privileged to host the 130th anniversary celebrations of the arrival of the railway in Barry’s Bay. Our iconic railway station and wooden water tower are truly one of a kind treasures.

The station houses a museum of railway artifacts, stories of local builders and heroes and is home to programs which celebrate local culture. The Water Tower Park, with its new addition of a train inspired play structure will continue to engage local families and visitors for years to come.

This anniversary celebration would not be possible without the interest and dedication of many who came before our group. The efforts of the preservation and restoration committees and local history and culture organizations ensured that the station did not come to the fate of similar stations in the area. The Township of Madawaska Valley and its Council have recognized and appreciated the value of the station and water tower park and provided ongoing financial support regarding structural and accessibility improvements. Local businesses have generously contributed to StationKeeper fundraising efforts on an ongoing basis. The StationKeeper membership continues to grow and fund ongoing programs and core volunteers spend endless hours unearthing facts and folklore. We would also like to thank the local media, in particular the Valley Gazette, for its promotion and support of our events during this anniversary year. This special edition devoted to our railway history will be a keepsake for many.

Joanne Olsen, President

StationKeepers MV intends to keep riding the rails for years to come. We welcome new members aboard at any time. Visit our website therailwaystation.ca or come meet us at the station!

“130 years is a remarkable achievement. The dedication of everyone involved is truly commendable. What a wonderful legacy.”

The history of logging in the Madawaska Valley goes back well before the train arrived.

In 1840 a few young men in their twenties explored the lakes and rivers of the area. James Skead and his younger brother, Robert, put two canoes into the mouth of the Madawaska River as it poured into the Ottawa River in Arnprior. Along with four friends, they paddled upriver, against the current, and deep into the Algonquin Frontier, a canoe trip of over 250 kilometres. It took two weeks to portage around 29 dangerous waterfalls and rapids, all carefully noted by James until his party arrived, with the first snowfall, at Bark Lake.

Rewritten from a presentation by Barry Conway at the Barry’s Bay train station early summer 2024.

Skead had so carefully mapped five years earlier. James also organized the Madawaska River Improvement Association bringing together local lumber kings, barons and princes -- people such as John Egan, Joseph Aumond, Robert Conroy, and Peter Aylen -- and got them to support his ingenious Madawaska River works scheme that would benefit them all.

There, the young men built a small log shanty, naming it Skead’s Depot. Nothing was heard of them for the rest of that winter. In spring, Big Jim and Little Bob, as the Skead brothers became known, returned to Arnprior, along with a raft of white pine. An impressive feat for the day.

Danial McLachlin, a lumberman in Arnprior, took notice. In 1842, he sent his best timber cruiser, a young Irishman named James Barry, up the Madawaska. Barry and a small crew canoed to the western end of Kamaniskeg Lake, a place the Algonquins called Beautiful Bay. From then on, the area was known as Barry’s Bay.

Within three years, the Madawaska River became internationally known as the most productive timber river in the entire British Empire. In 1845 alone, well over forty million board feet of square timber and saw logs were floated down the Madawaska to Arnprior. Big Jim, Little Bob, and James Barry made it possible. They supervised the construction of almost every dam, slide and chute built to get that timber safely past those 29 waterfalls and rapids that James

By 1857, settlers were arriving in droves along the new Opeongo Colonization Road that passed right by James Barry’s old shanty as well as Skead’s Depot. The Crown land agent in Clontarf, T. P. French, who was responsible for that new settlement road, hired James Barry’s cousin, Denis Barry, whose job was to take mostly Polish-Kashub settlers up to their Opeongo lots towards Barry’s Bay. The townsight of Barry’s Bay gained the double distinction of being named after not one but two Irish Barry's.

By 1867, James Skead became senator in the new Canadian Parliament, which was being built from timber harvested on the Madawaska.

John Egan died prior to Confederation. J. R. Booth soon took on his mantle. Booth bought Egan’s Madawaska River timber limits and won the contract to supply lumber for the new Parliament buildings, Booth had bigger plans than Egan.

Booth started replacing forestry and sawmill horses with steam engines; he also built a short railway to move logs overland to the Ottawa River and got involved in Great Lakes shipping. By the mid1890s, he was building the longest private railroad the world would then know. Booth’s Ottawa,

Continued on page 4.

Continued from page 3.

Arnprior and Parry Sound railway (OA&PS) passed right by James Barry’s old shanty in 1894 where Tom Murray spent the summer building Booth’s OA&PS railway as a waterboy. Murray, born near Barry’s Bay, was 14 at the time.

In a life spanning 101 years, Murray witnessed great changes to his birthplace, including watching James Barry’s old shanty eventually be transformed into a real home located at 33 Stafford Street. Early in the 1890s, Dan McLaughlin’s Lumber Company sold Booth

the land to build his railroad station in Barry’s Bay. Nearby land was subdivided and building lots were offered for sale. Along the shoreline of Barry’s Bay, McLaughlin saved the best water access for his own large, steam-powered sawmill the company he built once a train could bring up its heavy machinery.

Before long, Booth trains were passing through Barry’s Bay, loaded with timber that no longer needed to be driven down the Madawaska River past the 29 waterfalls. That same railway passing through Barry’s Bay would also eventually carry 40 percent of all Prairie wheat grown for export. Two hotels quickly sprang up in the village of Barry’s Bay, then three churches and dozens of wood-frame houses for sawmill workers and their families.

Barry’s Bay put out its welcome mat looking for any and all lumberjacks interested in hard work and steady pay. One of those who answered that call was John Omanique, a young Polish-Kashub.

While emigrating to Canada as a boy, Omanique got separated from his widowed mother and ended up alone in the United States. He eventually discovered that his mother had settled in Barry’s Bay and rejoined her around the time the railway first arrived. McLaughlin’s sawmill initially kept the lion’s share of the local lumber business. Still, there was room for local entrepreneurs. Murray and Omanique were two who heeded that call. By 1902, when Murray was in his early 20s, about the same as as James Skead was when he first saw Bark Lake, Tom formed Murray Brothers Lumber with his older brother, Mick. Eight years later, when the McLaughlin mill was put up for sale, the Murray brothers and Omanique saw a business opportunity. They formed Murray & Omanique Lumber and took over McLaughlin’s mill in Barry’s Bay.

Continued on page 5.

Peter Biernacki was on his way to becoming a much-loved Roman Catholic priest who eventually built St. Hedwig’s Church, St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic School and a nearby convent for an order of teaching nuns who ran the school.

Continued from page 4.

In order to help pay for all of that religious and educational activity, the town pitched in every summer for Father Biernacki’s famous fundraising picnics. Thousands of passengers got off the train in Barry’s Bay for a day of festivities. Crowds watched baseball games, marching bands, played games of chance, listened to federal cabinet ministers’ stump speeches and stuffed themselves with local cookery. Sometimes, they even got to watch Tom’s younger brother, Bill, perform his professional slack wire act. In winter 1910, Barry’s Bay got its first outdoor rink, complete with a onehorse zamboni, electric lights, and a rink boards good enough for both women’s and men’s hockey teams. All compliments of Murray and Omanique Lumber.

Tom Murray also heard the siren song of politics. He was first elected reeve of Barry’s Bay then spent sixteen years as MPP. Murray and Omanique had already started shipping by rail millions of board feet of dimensional lumber and square timbers all over North America each year.

The summer waters of Barry’s Bay seemed full of log booms, maneuvered to the mill by pointer boats and alligators, small steam-powered barges that worked like tugboats. Barry’s Bay became well known for turning such alligators into floating cookeries or sleep-aboard bunkies, perfect for a week’s work down on the lake. It is thought that the Mayflower, which sank Nov. 12, 1912 on Kamaniskeg Lake, hit a deadhead log which punctured its hull.

The 20th century also brought significant change. The First World War was over, the Ottawa Valley’s second great lumber king, J. R. Booth, passed away in 1925; and Murray and Omanique eventually dissolved their partnership in 1929, the year Tom Murray was first elected to the Ontario legislature. Omanique stayed at the mill in Barry’s Bay and reinvented himself as the Barry’s Bay Lumber Company; while Mick and Tom reverted to their original Murray Brothers Lumber Company; they soon built their own new mill at Cross Lake on the far side of Bark Lake.

Both companies somehow survived the break-up as well as the Dirty Thirties, as did the Princes, Rumleskies, Chapeskies, Dalys and dozens of others who ran local lumber companies.

The Second World War reduced local manpower significantly. The lumber industry was conscripted itself as an essential war service and those who remained at home were shifted into high gear. Diesel engines soon replaced most of the horses. During the war, Omanique eventually sold his mill

to John P. Conway and moved his company, first to Algonquin Park then to the Bonnechere River. He never gave up the name of his Barry’s Bay Lumber Company.

Omanique retired after the war, turning control of his company over to his son, Joe Omanique. The Murray brothers did much same, moving Murray Brothers to Madawaska where it remains today.

As for those thousands of young men in their twenties who followed Big Jim and Little Bob into the Algonquin fronter to spend winter nights having to bunk in timber shanties, if you stop long enough in Barry’s Bay, you may see some old ghost who will tell you a thing or two about pointer boats and alligators.

Toni

It’s hard to discuss the history of the Railroad Station without making mention of the rivalry between two influential figures, Canadian lumber tycoon and railroad baron J.R. Booth , and local businessman Frank Stafford who owned the first general store in the Bay known as “the People’s Store” that stood close to the Barry’s Bay Railroad station. Their controversy was legendary and many people in town recall the story. There are many versions of the tale, but we believe the following account by Bob Corrigan to be what most people believe to

The dispute between Frank Stafford and J.R. Booth resulted in the train station being removed for a time from Barry’s Bay to a point a couple of miles west of Barry’s Bay (Martin’s Siding). That happened in January 1895. Apparently, Mr. Stafford had given 2 acres and a right-of-way to J.R. Booth for free. Mr. Stafford was unhappy when the railroad company proceeded to install the water tank too close to his store, and Stafford felt that his store was in danger of being burnt by sparks from the locomotives. The problem was resolved before that summer ended.”

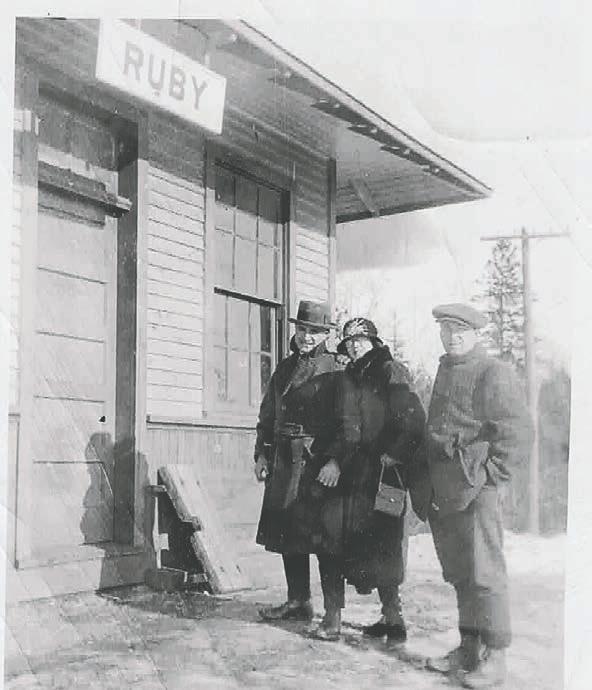

Press reports from summer 1892 indicate the first shovel went in the ground for the Ottawa Arnprior and Parry Sound (OA & PS) Railway on July 11.

The OA & PS was formed in May 1891 when the Ottawa and Parry Sound Railway merged with the Ottawa, Arnprior and Renfrew Railway. The section from Arnprior to Eganville opened Dec. 18, 1893 and the section from Eganville to Barry’s Bay opened Oct. 1, 1894. On Nov. 2, 1896, Madawaska became the divisional point on the OA & PS. A new five-stall roundhouse was built in Madawaska as a result.

From the Ottawa Free Press, July 11, 1892

“The first sod was turned today, at Arnprior, in the construction of the Ottawa and Parry Sound railway. There were no formalities observed, work along the line being simply begun in real earnest. It is understood that the contracts for the construction were signed this afternoon.”

A formal groundbreaking ceremony took place a week later on July 19.

From the Almonte Gazette, July 29, 1892

“CARP NEWS

The first sod. - on Tuesday, 19th inst., at 7 a.m., the first sod on the O.A. & P.S.R.R. was turned at Mr. Wm. Rivington’s farm near this village. The ceremony was performed by G.N. Kidd, Esq., Warden of Carleton County, and was witnessed by a large concourse of the inhabitants, amongst whom were several gentlemen from Ottawa - Dr. G. Falls, Dr. Pearson, John Kidd, Esq., barrister, and F.O. Hirsch, Montreal. As the sod was duly placed in position in the center of the road the assembled crowd manifested their approbation by rounds of cheering and applause. The ceremony was witnessed by Geo. A. Mountain, C.E., A.H.N. Bruce, C.E., Robt. Bruce, C.E. Arthur Simpson, Esq., Messrs. Fauquier Bros., Dr. Groves, Messrs. D. McElroy, Thos. J. Armstrong, Wm. Barton, Thos. Hodgins, John Carruthers and others. In the evening the warden entertained the engineers, contractors and chief promoters of the railway scheme to supper. The table being cleared, Mr. Kidd, in proposing the health of Her Majesty, said he considered this the most important day Carp had witnessed

for many a year. He was very pleased to have the privilege of thus meeting the chief engineer and his staff, together with the contractors and so many interested friends. Thereafter Dr. Groves proposed the health of the president of the road, John R. Booth, Esq. In the absence of Mr. Booth, Mr Charles Mohr, Reeve of Fitzroy, responded. Mr. Thomas J. Armstrong proposed the health of the engineering staff, to which Chief Engineer Mountain, Messrs. Bruce and Simpson replied. Mr. Sullivan, one of the staff, sang in fine style “Our Jack’s Come Home Today.” The toast of “The Contractors “ was next given by Mr. David McElroy. Introducing the toast Mr. McElroy proposed a conundrum, “Why did the road not go via Tolbolton?” Answer: because it was too monotonous, had too much mohr (moor) and no Mountain nor Groves on that route!” Messrs. Fauquier and Brennan replied. Mr. Mohr proposed the health of the chairman, to which Mr. Kidd responded in a lengthy speech. Auld Lang Syne and God Save the Queen brought the harmonious gathering to a close at an early hour.”

On March 1, 1959, Candian National Railway began Dayliner service between Ottawa and Barry’s Bay. Dayliners were self-propelled, air conditioned cars for passenger travel. They were also called Budd Cars after the company that built them, The Budd Company. Passenger service between Ottawa and Barry’s Bay was discontinued July 7 1961. The last train left Ottawa at 8:10 p.m. Canadian Pacific abandoned Eganville subdivisions between Douglas and Eganville and Payne and Douglas on Dec. 16, 1970 and Feb. 20, respectively. On Jan. 20, 1966, the Dominion Lime Products (aka Bonnechere Lime Works) closed. The lime industry had a long history in the region, dating to about 1907. The closing of the plant at Eganville meant the end of the last narrow gauge railway in the area.

-Source, Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages and Old Time Trains

Robert Fisher

John Rudolphus (J.R.) Booth built the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway (OA & PS) to haul timber from forests to mills in the Ottawa Valley. Just under 264 miles long, the railway wasn’t lengthy but it was important. For a time it was the busiest railway in the country. In addition to timber, the railway carried as much as 40 per cent of western grain, picking the grain up in Parry Sound and transporting it to Ottawa. Booth owned timber rights in, what is today, Algonquin Provincial Park and a mill in Ottawa. In addition to the OA & PS, he also bought the Canada Atlantic Railway (CAR) which ran from Ottawa to Vermont, thus assuring a route to the United States for his timber. The lines were consolidated in 1899 and sold to the Grand Trunk Railway company in 1905.

All that remains of the roundhouse in Madawaska are some remnants of the foundation. The turntable rotated cars to one of five bays.

company wanted to get it open before Booth got his OA & PS finished. The CPR beat Booth to Eganville and, as a result, Booth re-routed his road about a mile southwest of town. Courts decided which company would get land near Killaloe. Booth had been deeded the land. The CPR wanted it. The court sided with Booth.

The OA & PS was not Booth’s first rail line. In 1884, he built a five-and-a-half-mile line from Lake Nosbonsing to Lake Nipissing; the Nosbonsing and Nipissing Railway (NNR)

The OA & PS started as two separate lines. The Ottawa, Arnprior and Renfrew Railway which went from Ottawa to Renfrew and the Ottawa and Parry Sound, which went from Renfrew to Parry Sound. The two lines, chartered in 1888 were consolidated into the OA & PS in 1891.

The first shovel went in the ground in 1892 and a section from Ottawa to Arnprior was opened in 1893. Railways were big business at the time and several lines operated in competition. Booth’s OA & PS competed with Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and east-west lines the CPR was building. The CPR Atlantic & North-West line was planned and the

The first train ran the entire length of the OA & PS route on Dec. 21, 1896. While named the OA and Parry Sound railway, the line did not run to Parry Sound. The town and Booth had a disagreement over cost for land at the harbour. Parry Sound was, at the time, the deepest freshwater port in the world. Booth took advantage of a law allowing expropriation of Indigenous land for rail lines and made the endpoint of his line at Depot Harbour. In 1898, he added a steamship company, the Canada Atlantic Transport Company which allowed him to take cargo by land and water faster than any other company.

Several private spur lines connected to the OA & PS as did the NNR. A divisional point; a local headquarters for a rail company that is often an important maintenance depot, was built later at Madawaska along with the roundhouse.

The CAR officially took over operation of the OA & PS in 1899 and the OA & PS name ceased to be used. Grand Trunk Railway bought the CAR in 1905 and by 1910, trains ran every 20 minutes there was so much business.

Grand Trunk went bankrupt and, in 1923, the federal government nationalized the line, merging it with the Canadian National Railway (CNR).

When it comes to a passion for the railroad and a love of history, local boy Mark Woermke is someone with a great deal of knowledge about the topic.

Hosted by the StationKeepers MV as part of their celebrations to commemorate the 130 th Anniveersay of the railway in the Bay, Mr. Woermke recently gave an informative presentation on the people who kept the local train service moving and on track, the employees of the Barry’s Bay Railway Station spanning a period of seventy-eight years.

Not only is the topic one he is enthusiastic about, it’s also personal.

“Without the railway, this station, and the people who worked in it,I wouldn’t be here today. I mean that literally. My parents met here when they were railway employees.

But beyond that, I have benefited from three generations of association with this railway and this station: my father started his CNR career here, my paternal grandfather raised his family on a section foreman’s wages along this line, and my maternal great grandparents owned and operated the Balmoral Hotel whose existence was tied to the railway.”

He acknowledged other people in attendance who had relatives who worked at the Station in the past.

Among them was Daniel Gutoskie (son of Leonard Gutoskie), Jane Foster and sister Mary Recoskie (daughters of Donald Recoskie), and Jean Sayyea and her sister Patsy Terreberry (granddaughters of Albert Fox).

The Railway’s vital role in the history of Barry’s Bay

Mr. Woermke noted that the arrival of the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway “was the most important event in the history of Barry’s Bay. Without it, Barry’s Bay might not have developed, or it would be a very different community.”

He went on to explain that in the railway’s heyday “large lumber operations, smaller local mills, the corundum mines at Craigmont and the turpentine plant in Barry’s Bay all depended on the railway to ship their products.”

Area farmers “ shipped livestock, milk, and other agricultural products to city markets and received new agricultural equipment on the train. Shopkeepers and citizens depended on the railway to bring their groceries, household supplies, mail, parcels, catalogue orders and newspapers.”

Mr. Woermke gave lots of examples of how the trains provided for passenger travel as well. “ It transported doctors in, and critical patients out; and it was the means by which, when necessary, police, coroners and magistrates arrived in the community, Moreover, it provided an opportunity for locals to travel for leisure, to honeymoon, to attend to business, to go to college, or to enlist for military service.”

He also reminded us that at the time, the telegraph, facilitated though the railway staff was the only means of rapid communication and that people and businesses relied on it to send important and urgent messages and news be it local notices or that of national importance.

While the railway may have been the heart of the village, it was only as good as the staff who kept everything running. Mr. Woermke detailed the roles and responsibilities of the

Toni Lavigne-Conway

The presentation of employees included some very interesting personal facts gathered and addressed Woermke. Some are noted below.

• Frank Milloy was probably Barry’s Bay’s first agent. The earliest reference to him is an 1895 land transaction where he is identified as the station master and one of the trustees of the Barry’s Bay Methodist congregation. No doubt he was caught in the conflict between local businessman Frank Stafford and the railway which caused the station to be closed, moved several kilometers west, and returned to the village.

• In 1895, the Barry’s Bay correspondent reported in the Eganville Star that agent Fred Eastman was the first bicyclist seen in the neighbourhood.

• On May 2, 1899, The Ottawa Citizen reported that “Mr. Casey,” station agent at Barry’s Bay, had left his position so that his wife might claim a $100,000 inheritance.

• In 1911, Philip Lawler , his wife, Annie Vancuski, and their infant daughter, were living in the agent’s quarters above the station. As agent, Philip would have interacted with victims, survivors, officials, investigators and reporters in 1912 when the steamer Mayflower sank in Lake Kaminskeg on its way from Barry’s Bay to Combermere with a loss of nine lives.

• Harry Taylor arrived during one world war and left during another. A Madawaska native, Harry signed on with the railway at Madawaska in 1913 and had four brothers who were railroaders. Two were agents, one was a brakeman, and another was an engineer. Arriving in Barrys Bay in 1917, his tenure here lasted until 1940 making him Barry’s Bay’s longest-serving agent.

consult the booklet Agents, Operators and Clerks at the Barry’s Bay Station 1894-

for biographical sketches on the individuals listed above.

various positions held at the station.

“Sometimes called “station masters” Agents were the railway’s sales reps in the community. They sold, delivered and supervised, all the freight, passenger and telegraph services required by individuals and businesses.”

They also received orders by telegraph, maintained detailed files and ledgers and were responsible for keeping the office clean and stocked, the station waiting room tidy and warm and kept freight shed and grounds secure, organized and safe. According to Woermke, “sometimes agents were referred to as “agent-operators” because they had to be qualified telegraphers.”

The Operators had the important job of operating the telegraph machine and facilitating communication. It was explained that “the telegraph poles that lined the railroad track held two lines. One was for railroad communication, and the other was for commercial telegrams. If stations were small, agents would be responsible for both railway and commercial telegrams, but if stations were busy, operators handled the public or commercial telegrams. At times, the commercial telegraph companies were

separate entities from the railway and operators worked for them.”

Clerks assisted agents when things got busy at the station. “Clerks may have had specific responsibilities like freight and express, or they may have been assigned tasks like delivering telegrams, calling customers, preparing reports, filing, cleaning, maintaining kerosene lamps, and stoking the coal stove. Often, clerks were gaining on-thejob experience for future careers as operators and agents.”

Meeting the People that made it all happen

Before introducing the railway staff, Mr. Woermke acknowledged that although he’d done months of research in preparation for the presentation, he was not aware that a complete roster of all the personnel existed and that his work was still one in progress.

“It’s also a starting point, and the list is growing. In the last two weeks, I’ve added three more people.”

He presented the names in order of dates, also noting significant events in history (like the wars, the depression, major economic developments ) that would have affected both the railroad and the staff.

• Bert Needham. When the artist Tom Thomson drowned in Canoe Lake in 1917, station it was Bert, agent at Algonquin Park and former operator in Barry’s Bay who sent the following telegram message to Thomson’s family in Owen Sound: “Tom Thomson drowned in Canoe Lake. Body found. Now awaiting burial there. [ In 1952, Bert attended a ceremony at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa where the “Canada Atlantic Old Boys” organization placed a wreath on the grave of the founder of the Ottawa Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway, J.R. Booth.

• When he retired in 1949, Alfred Fox was Barry’s Bay’s second-longest-serving agent. One of Alfred’s sons, Howard, a World War II veteran, married Mary Etmanskie, and they raised their family in Barry’s Bay.

• Gwen Billings was hired as a railway clerk during World War II. Like other railway staff, she received heartbreaking news about families during wartime, and her experience of delivering two telegrams to the Biernacki family in 1944 was shared. The operator received the first telegram informing them that their son had been killed in action. Gwen was chosen to deliver the message because she knew the family. She telephoned the soldier’s uncle, Monsignor Biernacki, and together they delivered the terrible news. About a month later a second

notifying the Biernacki’s that another of their sons had been killed.

• Roy Woermke started as a clerk in the Bay in 1943, but he only worked there for about eighteen months before going out on the road as a relief operator, working in at least sixteen stations in Eastern Ontario before 1951 when he was appointed agent at Lake Traverse Station in Algonquin Park. He married Gwen Billings that same year. In his retirement, Roy chaired the Railway Station Restoration Committee and served briefly as a councillor for the Village of Barry’s Bay.

• Don Recoskie was a young lad from Wilno when he started his railway career as a Clerk. By 1957 he was working as a relief operator at various stations including Barry’s Bay and in 1960 he became a

permanent operator in the Bay, continuing to work there until 1963.

• Len Gutoskie, who grew up on a farm on the outskirts of Barry’s Bay, was sixteen when he started at the station as a Clerk in 1942. In 1947, Len likely set a record for the Barry’s Bay station when he sold a ticket to resident Frank Ritza who was embarking on a journey to Mexico City. Len learned telegraphy and went on to work as a relief operator in Eastern Ontario stations including Maynooth and Alexandria. In 1949, he married Yolande Blais and eventually he returned to the Bay as an Operator in the early 1950s staying until 1957 when he was appointed agent in Wilno.

• Barry’s Bay’s last permanent agent wasJack Beach. Jack’s father, Tom Beach, had a long career with the

Daughters of Donald Recoskie (Jane Foster and Mary Recoskie of the Kitchener) remember they had strict instructions not to touch the telegraph machine. “Dad was very proud of his job and always loved the area. We also remember it being tough on mom to be home alone raising us kids when they decided that dad would go on the road to work as an operator across Ontario.”

railway, and Jack’s brother Gerry also worked at the Barry’s Bay Station. Jack and his family lived in the agent’s quarters above the Station where one daughter broke her leg falling on the stairs, before moving to a larger home on Bay Street. He was known for his cheerful disposition and community involvement as a member of a school board committee, a community centre board, the chair of the Association for Community Living, and he was involved with local service clubs.

Mr. Woermke closed the presentation by acknowledging that the railway staff “witnessed and participated in significant events that affected the development of the village of Barry’s Bay, the life span of the railway and their own personal lives and, by doing their jobs, they contributed to the growth of this community.”

He then invited audience members to share their own stories and recollections about the days of the local railroad.

Daniel Gutoskie youngest son of the Len Gutoskie remembers little chicks being delivered on the train, and how his family had one of the first television sets when his dad was an agent at the Wilno station. “All the area kids would come over to watch a cowboy movie. We also had a phonograph player in the station and had a lot of fun dancing in there.” Len Gutoskie, Clerk/Operator.

For well known local historian and genealogist Theresa Prince, preserving the history of her hometown, including the historic Railroad Station, came quite naturally.

“ I always had that interest (in history) in me. I remember in grade one when I started school, and the teacher would ask what your mother’s maiden name was. I knew that but all the other children didn’t. They would just say, it’s mom. And when I became a widow very suddenly in 2000, I also wanted to know more about my husband’s family too, but when I started that I thought I should do mine first, so I switched back to my own.”

Ms. Prince would later go on to research and subsequently find an abundance of historical information dating back to the 1800’s, during the time when the Railway, that was mostly driven by the lumber industry, was the heart of Barry’s Bay, it’s economy, communication and daily life.

“When I was looking at my mom’s side of the family (she was a Kovalskie) I wanted to know what Barry’s Bay was like from her growing up, so I began researching the early settlers and the businesses that existed back then. Of course,the railway was a big a part of the history of our town.”

In doing her research she realized that unfortunately, stories and information of long ago were not always recorded or written down like that might be today, which sometimes made it harder to gather information.

“I wish we had asked our families more about the town and the railroad station. We never asked and wish we had .” Her interest in that era would also motivate her to later become a founding member of the StationKeepers MV, a non-profit group committed to preserving the history of the Railway and the local Station building in Barry’s Bay. Despite never having ridden the train herself, she does have personal stories of the days of the train in the Bay.

Toni Lavigne-Conway

“As kids, we could hear the sectioncar coming through town in the afternoon as we walked home from school. If we were dallying and heard that we knew it was around 4:30, so we better get home,” recalled Theresa, noting their family farm was a good three mile walk each way to school. Even from there, she says they could still hear the train whistle blow every day from the farm.

“I also remember all the box cars sitting behind Palubeskie’s general store; that’s where the pulp was loaded. There was always lots of activity there. I know some of the town kids would tell us stories of playing in those box cars. And other people remember when pigs were shipped by train. There was some fencing around where the Water Tower is now, and they would have the pigs ready to load them onto the train.”

But one particularly special memory that brings an soft smile to her face, is one that also speaks to the strength and resilience of her mother, who like many others, relied on the train for the delivery of goods and services.

“Every year my mom always ordered baby chicks from the hatchery in Renfrew, and they would come here on the train. She would walk the two miles to town to get them because we didn’t have a vehicle, and she’d have to hire a taxi to bring the chicks back home. We were always so excited. They came in a big wooden box with little holes in it so the chicks could get air. I imagine my mom would have had to write a letter to order them and send it through the post office.”

Stories like these demonstrate the significant role the railroad played for the town and families like Ms. Prince’s, since chicks like these were not just cute, little animals, they represented future food, income, and the ongoing cycle of farm life for many local families.

Editors note: This Christmas tale was told by the late Arthur Rumleskie to Dave McBride of Madawaska. Dave recorded Arthur’s memories and submitted them to the Valley Gazette just in time for Christmas. Arthur was a local historian, who passed away on April 15, 2010, at 92 years of age.

In the 1930s, there were no snowplowed roads in the country in the winter months. The only snowplowed road through the Valley was the railroad. On Christmas eve, people would ravel to the villages by horse and cutter from their country homes to do their Christmas shopping. The stores were open ‘til 10 p.m. Christmas eve. Later on, they would go to the church for midnight

services. Back then, Charles and Dan Murray owned the original Frank Stafford’s general store in Barry’s Bay. There were 25 horse stalls built behind the old store which extended from Highway 60 to the railway right-of-way. Teamsters would tie and feed their horses there while they went shopping in the stores.

There were crowds of people shopping in Murray’s old general store in Barry’s Bay. It was a busy place in the 1930s around 6 o’clock in the evening. Somebody shouted outside the old store: “The Christmas train is coming! Hear the whistle blowing for the Wilno crossing!” People went from the store to the CNR railway station, the Christmas passenger train blew its steam whistle once more for Murray’s railway crossing then the train stopped at the station.

There were crowds of people gathered at the station. Passengers would disembark from the train coaches. People were busy meeting relatives and friends at the station in the 1930s. Men wore the long old fashion overcoats with an inside pocket on the left side of the coat. One man meets his good friend. They shake hands wishing each other a Merry Christmas. While they were standing having a little chat together near the locomotive engine, one man pulled out a mickey of whiskey in the midst of the steam from the train engine. Even the engineer or Constable Bill Johnson would have hardly noticed the two men having and enjoying a little Christmas cheer near the engine. It was the most joyful time of the year. After the commotion was over, the Christmas passenger train would back down the tracks a short distance to take on water at the water tower for its journey to

Madawaska and Whitney.

The water tower was between the station and Murray’s old store. After taking on water, the train pulled up to the station and stopped.

Then, in a few minutes, the conductor shouted, “All aboard!”

The engineer blew two short whistles and rang the bell. The train began to move slowly away from the station on its journey to Madawaska and Whitney. The train blew two long whistles for the Paugh Lake crossing.

The Christmas passenger train began to pick up speed. In less than a minute, the train blew two long whistles for Martin’s Siding Road crossing. The train was gone bringing with it Christmas cheer to the people of Madawaska and Whitney.

Fond memories of Christmas eve at Barry’s Bay in the 1930s.

THE RENFREW MERCURY, AND COUNTY OF RENFREW ADVERTISER.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 5, 1894. An Enticing Excursion - Through the Wilno Pass to Barry’s Bay - Next Tuesday, 9th Oct.

The Renfrew Masons of the old A.F. & A.M. degree and those of the more recently organized Royal Arch Chapter - have combined their forces and announce the most attractive excursion of the season for Tuesday of next week. It is over the O.A. & P.S. Ry. to the western part of the county, just opened up by that line. The excursion will leave Ottawa by the regular train departing at 8 a.m. and passing Renfrew at 9:50. Arriving at the celebrated Wilno Pass - the disputed pass which gave birth to the long legal fight between the C.P.R. and the O.A. & P.S. - the train will be stopped long enough to give excursionists an opportunity to climb the mountain, and view the scenery: which those who have seen it declare to rival the highlands of Scotland, and to exceed in beauty the famous Adirondacks. Four lakes can be seen at once from the top of the hill. The train will pass Round, Golden and Silver lakes: and reach Barry’s Bay about noon. In this neighborhood of delightful hunting and fishing grounds the train will remain until 5 o’clock, when a special train will make the return trip. Return fares - from Ottawa, $1.50; Carp, $1.40; Kinburn, $1.30; Galetta, $1.25; Arnprior, $1.25; Glasgow, $1.00; Renfrew, $1.00; Admaston, $1.00; Douglas, 90c.; Eganville, 80c.; Golden Lake, 75c.; Killaloe, 50c. Children, half-price. A refreshment car will accompany the train, and hot lunch can be procured. If the day is fine, an enormous crowd will probably take advantage of this trip into hitherto unknown country.

Submitted by Robert Corrigan

bolder and more mountainous in appearance; but the approach to that height of land is so gradually upwards, that the scenery is no more striking than is to be seen in other parts of the Free Grant districts in other counties. The sky had been overclouded about the time the train started; but began to clear before Barry›s Bay was reached; and although there was a keen wind blowing, the weather enabled the excursionists to enjoy wandering around. The Bay is about three-quarters of a mile from the station; and some of the party were soon taking their picnic meal there. Across the bay a substantial house and well cultivated farm were visible: but the steamer to Combermere, which some expected to be there, was not to be seen. The soil between the station and the shore of the bay is sandy: and though some deserted buildings and unfinished foundations are to be seen near the shore, now that there is railway communication,

with a Journal reporter last evening he stated that the three men who met their death were “loading a hole” with dynamite, had placed three cartridges in position and were about to place a fourth when the explosion occurred, from what cause will never be explained. The three men were blown many feet high in the air and one of them named Geo. Marsten from Carlow was killed outright.

«Another named William Kellar of Palmer›s Rapids, lived for an hour and the other an unknown Englishman died four hours afterwards. The bodies were horribly mangled. During the night coffins were made in which the remains were placed. Kellar›s remains were taken to his home at Palmer›s Rapids, the other remains were buried in the vicinity.»

«The accident occurred in a part of a rock cut at the western outlet of the Hagarty Pass. Between fifteen and twenty men were working within a few yards of where the explosion occurred.»

THE RENFREW MERCURY, AND COUNTY OF RENFREW ADVERTISER.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 19, 1894.

The Excursion to Barry’s Bay. The excursion to Barry’s Bay, on Tuesday, the 9th inst., under the auspices of the Renfrew Lodge A.F. & A.M., and Bonnechere Chapter of Royal Arch Masons, was well patronized, - there being about 250 excursionists on board the train when it left the Renfrew station: about 100 being from Renfrew. The number was added to at the other stations - Admaston, Douglas, Eganville, Golden Lake and Killaloe. The number from Renfrew would probably have been greater, had it not been for the excursion to Ottawa, to hear General Booth, of the Salvation Army. A chief attraction of the Barry’s Bay excursion was the opportunity afforded to see the country opened up by the Ottawa & Parry Sound Railway: the free grant settlements in the Opeongo Road district being unknown territory to many of the residents of Renfrew town. There is a marked contrast between the first few miles out of town on the Kingston & Pembroke and on the new road. On the first named, rocky hills form the prominent feature in the scenery long before - and after - Calabogie is reached: while on the new road, throughout the greater part of the township of Admaston, the cleared and cultivated farms of the Bonnechere Valley are seen. From Douglas westward the ground is rockier and stonier, and what clearings there are show how unattractive were the surroundings of the earlier settlers on the Opeongo Free Grants. Passing glimpses of Mud, Golden, Round and other lakes, break the monotony of the “bush” along the line. It is not until the Wilno Pass is being neared that the hills become

it is probable that Barry’s Bay will in no long time be fairly settled between the station and the bay. - Some of the excursionists had taken their guns along, hoping to do a little hunting. But the noise of the popping off of guns was of rare occurrence; and no big bags of game were brought in - and no fish stories were recounted. All the game within some distance of the line, it is said, has been cleared off, for the time being, by the Italians who were working on the construction of the line. The roadway is smooth and in good order: and as opening up a hitherto comparatively unknown district, the first excursion is likely to be the fore-runner of many more in years to come. The younger generation, with their High School and College notions, have now a chance of seeing up there, what the backwoods of Canada were, which their fathers cleared.

The «George Marsten, of Carlow,» was the only son of Mr Marston, who, many years since kept the Basin Depot house, at Barnet & Mackay’s depot at the Basin. Mr Marston subsequently kept other stopping places between Renfrew and the Basin Depot. For a time he removed to Renfrew, and kept a store in lower centre town. George was then a growing boy of about a dozen years of age, and gave promise of turning out a young man of good character and disposition. His father, after leaving Renfrew, took charge of Mr McGuire’s lumbering farm near Mattawa, and still resides there. Mr and Mrs Marsten came down by the C.P.R. from Mattawa, and took the O.A. & P.S. train to attend the funeral of their unfortunate and lamented son.

2 Articles about the explosion that appeared in the Renfrew Mercury

THE RENFREW MERCURY, AND COUNTY OF RENFREW ADVERTISER.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 10, 1894.

The Fatal Dynamite Explosion. The Ottawa Evening Journal of Friday last, published the following account of the dynamite explosion, mentioned in last week›s Mercury. It will be seen that it varies from the report received here as to the number of men killed and injured:

«The particulars of the dynamite explosion on the O.A. & P.S. Ry. construction at Barry›s Bay, which resulted in the loss of three lives as mentioned in yesterday›s Journal, are now at hand.

«Mr G.A. Mountain, chief engineer of the O.A. & P.S. railway returned to the city last evening from a trip to the vicinity of where the accident occurred. In conversation

THE RENFREW MERCURY, AND COUNTY OF RENFREW ADVERTISER.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 17, 1894.

The Enterprise, in its report of the late fatal dynamite explosion at Barry›s Bay, says that the foreman, Raymoud Dunning, was within six feet of the charge when it exploded, and was blown, by the concussion of the air, fully 150 feet up the side of a hill, but fortunately fell on a brush heap, and in a few minutes was able to get up. Marston was found about thirty feet from the point of explosion, resting on his knees and face. He was still breathing, but unconscious, and died in twenty-five minutes. One arm and one leg were broken; the upper part of his face filled with gravel, and his breast injured with stones. Wm. Deer had his clothes completely torn off; and one leg and one hand had been blown off. He was delirious, sometimes calling on his mother. He died in about three hours. He was from England and had been in Canada about a couple of years, and the day before his death had been saying he would go to see his mother next year. Louis Kellar’s body was fearfully mangled, being disembowelled. He was from Palmer Rapids, and leaves a wife and four children. He and his brother intended to start for home the next day. - The remains of young Marston were taken by his sister, and brother-in-law, Wm. George, who reside at Barry’s Bay, to Eganville, and interred in Melville cemetery: Rev. Mr Rattray officiating at the funeral. - Mr M.J. O’Brien informs us that the foreman was not blown so far, as abovementioned; but only about 20 feet.

Toni Lavigne-Conway

Barry’s Bay may not be her hometown but, for Cathie Corrigan, it’s definitely home. It’s also the place where she travelled by passenger train from Ottawa in the summer of 1960 to attend a girls’ camp called Tekakwitha, located on Lake Kamaniskeg.

She still has vivid memories of the night she disembarked at the historic Railway Station that sits in the heart of Barry’s Bay.

“I remember we arrived from Ottawa in the dark one night and it was pouring rain. Some local men and boys came around with cars to drive us to the camp which was located just behind where the old Polish graveyard is on today’s Kartuzy Road, just off Siberia Road.”

Coincidentally, one of the fellows that came to pick up the girls that night was none other than local boy, Bob Corrigan, and although she didn’t officially meet him then, he would later turn out to be the man she would marry.

“I remember when I met Bob years later and we began dating, I was shocked to hear that he came from the Bay and that he had a connection to the Camp. I also remember that, when we were at the camp, a bunch of boys would row by in their boats to wave at us, and we, of course, always waved back. I’m pretty sure one of them was Bob!”

Besides this isolated encounter at the Barry’s Bay Railroad Station, Cathie says she really didn’t have any other connection to railroads or trains other than the fact that her grandfather had worked for the CPR in Ottawa. But that didn’t stop her from becoming passionate about doing her part as a volunteer to help preserve the history of the Station. Cathie would also go on to play a huge part in helping to develop what would later become a museum of artifacts that would delight both local residents and visiting tourists.

After marrying Bob, the couple settled in the Bay where they still live today. Cathie worked as a nurse, and Bob as a high school teacher, and together, they raised their four children here.

Cathie first became involved with the Station through Bob’s affiliation with the Railway Station Restoration Committee, and sometime in the mid-90s she assumed the role of volunteer Curator at the Station. “ Marion Atchison was doing the job at the time but was wanting to leave and I remember her saying, ‘Oh, you’ll just come in and clean a bit.’” When Cathie started that job, there was already an Information Centre operating out of the building in the summer months and the South of 60 Arts Centre had taken up residence there seasonally as well. As part of her Curator’s role, she was keen on collecting and restoring railroad artifacts. “I remember that I had a little section in the middle of the building where I displayed some of the items I’d gathered. Later, we had a cabinet built to display some of the smaller things and keep them protected. ”

Cathie says she got most of the museum pieces from local residents or from those visiting the town. “Lots of people stopped in to get information and then saw some of the train things displayed. So many people were very generous and just wanted to see things preserved.”

There is one particular story of kindness that she and her husband Bob remember in the early days of her volunteering. “One Saturday morning, we went to a garage sale on a property just south of town. We noticed there was a neat train item there, but it had a big price on it, more than the museum could afford. We asked the seller if he might be willing to sell it to us for less, mentioning our affiliation with the Station. But he wouldn’t lower the price. That’s when another man at the

sale overheard our conversation and said that he would like to buy the item for us. And he did, with his own money. It was so nice of him. That man was Pat Hickey and his wife, Frances Skebo.”

The quest for more artifacts continued with an idea to secure an old caboose to serve as a complementary historical landmark for the Station. A search began and, in 2004, some friends told Cathie they’d seen what turned out to be a vintage 1922 red caboose, south of Ottawa, in a campground called Hither Hills, that was then being used as a trailer.

“Our friends talked to the owner about us looking for a caboose, but the camp operator said it belonged to her husband who was a train buff and that they weren’t interested in parting with it at that time.So, I wrote the woman a letter, telling her all about our community’s history with the railroad and how we’d restored the Station and the Water Tower and that, if they ever wanted to part with the caboose, to please contact me.”

Years went by before Cathie received a surprising phone call from the owner, Ruth Millar, who said that her husband had passed away and she was ready to part with the caboose. She was even willing to donate it to the Museum.

As wonderful as that was, there was now the issue of how to get it to the Bay intact, but that problem was solved once

again by Mrs. Millar and her family, who offered to donate $5,000 towards transportation costs. “They were so very generous, and they didn’t even have a single connection to the area. They just appreciated that it would continue to be a part of history.”

It took months of planning that included a few delays, but when the momentous day came, a convoy of trucks carrying the caboose, wheels, and equipment, pulled into the Water Tower Park, and the old Caboose made its new home in Barry’s Bay.

Securing the caboose and getting it here, however, proved to be only half the battle since restoration of this historic beauty was also needed to ensure it would stand solid for years to come. Once again, the community stepped up to support the project with donations of money, supplies and labour.

Cathie explains that “structural work and painting took place in 2012, thanks to Don Webb and Sandy Kingsmith. They had the knowledge and expertise to do the muchneeded work; without them, we would not have the caboose today.”

In 2015, a local roofer, Rod Turner, offered to donate his time and materials to replace the roof.

“So many people have made this project come to life. Their generosity is truly amazing,” said Cathie.

As to how the caboose came to sit at the Water Tower Park, Cathie invited the members of the Station Restoration Committee to go for a walk around the property and give their opinion on where it should be placed. After careful thought, they all agreed that the best location for it would be the Park so that its size wouldn’t detract from the Station itself and the park area around the Station could still be used for other things.

Today, residents and visitors enjoy being transported back in time every time they set eyes on the restored caboose, perhaps even thinking of the train conductors and brakemen that would have used the car as their office and living quarters back in the day.

Rail travel was a boon to the logging industry. It made travel simpler and quicker. The early days of the railway were also dangerous days. Numerous derailments occurred, trains colliding with each other and, sadly, many lives were lost. Often young lives. These are a few of the wrecks and derailments that happened in the Eganville to Whitney stretch of the road. Derailments and other collisions would bring numerous people out to the scene, almost like a social event for the townsfolk.

From the Ottawa Citizen, January 21, 1897 THREE MEN KILLED FREIGHT TRAIN WRECKED ON THE PARRY SOUND RAILWAY. A Run-Off Above Barry’s Bay, One Hundred and Ten Miles from Ottawa, in Which a Fireman and Two Brakemen Lose Their Lives.

The unusual record of immunity from serious accident which the Ottawa, Arnprior & Parry Sound railway has enjoyed since it opened for traffic, was broken last evening by a casualty which occured near Barry’s Bay, resulting in the death of three train hands and the injury of another.

The killed are:

Charles Hutchison, fireman, aged 26, single. James Casselman, brakeman, aged 45, married. William Russell, in charge of store car, aged 35, married. The injured man is William Taylor, engineer, scalded about face and hands.

car special, in charge of Superintendent Donaldson, and having Dr. R. W. Powell on board, left for the scene of the accident at 11 o’clock. At Galetta the train was met which had been despatched down from Barry’s Bay with the two injured men on board, Taylor and Russell. The latter were being attended to by a doctor who boarded the train at Renfrew. Russell was found to be fatally injured, and he died just before the train reached the Carp.

The Disaster.

The train to which the accident occurred was No. 60, way freight, which left Ottawa yesterday morning at 8:30, in charge of conductor Aris and engineer William Taylor. The train as it left Ottawa consisted of 27 laden cars, and was doubtless still a very heavy one when it reached Barry’s Bay at 7.15 last evening.

Four miles above Barry’s Bay is a short side track, known as O’Brien’s siding. It was here the disaster occurred.

It appears that the train was running along at a moderate speed. Just as the siding was reached the engine jumped the track, through what cause is not yet known, although it is surmised that an open switch had to do with the run-off. Two cars were standing on the siding. Into these the derailed engine crashed and was thrown into the ditch, falling upon her side. Several of the cars following were also derailed and over-turned. When conductor Aris, who was in the van at the rear, reached the engine he found engineer Taylor groping about the cab blinded by scalding steam, and fireman Charles Hutchison crushed in between the engine and the embankment. With the assistance of the train hands the poor fellow was extricated. He was still conscious and able to speak but his injuries were of such a nature that he survived his rescue but a few minutes. Casselman, the forward brakeman of the freight, was also riding in the cab. When the crash came he was thrown over into the embankment and wedged in between the tender and the car following. He lived for an hour or so after being taken out and laid in the van, being quite conscious and able to speak a few words to his mates. He died, however, before the first relief arrived. Russell was badly scalded, but not until he was examined by the doctor at Renfrew, two hours later, was the extent of his injuries known. These, eventually, proved fatal, the patient expiring on the way down to Ottawa. So soon as the dead and injured were removed from the wreck a train hand was sent back to Barry’s Bay for help. At that station there was a locomotive on the siding, and with a car attached she was dispatched to the scene of the wreck. This relief train made the return journey to Ottawa in quick time, only remaining at Barry’s Bay long enough to land the bodies of Casselman and Hutchison at the station.

The train consisting of a locomotive and van, with the injured engineer and the body of Russell on board arrived at the Elgin Street Station at 12.45 this morning. Engineer William Taylor, accompanied by Dr. Powell, was driven in a cab to his house at 291 Nicholas Street. His face and hands were bandaged, but he stepped from the van without signs of weakness, and to the inquiries of a group of fellow-employees gathered at the landing, returned the cheery answer that he was all right. The doctor’s report, while somewhat less sanguine, gave the impression that he considers the patient in no immediate danger.

The body of William Russell was taken to Roger’s morgue where an inquest will probably be held. The news of his death was broken to his widow at midnight, at her home on First avenue, by a kindly neighbor. The poor woman’s grief was uncontrollable. She is left a widow with two small children. For the intelligence of her son’s death, Mrs. Hutchison was not holy unprepared. The telephone call from the Canada Atlantic office, sent about eleven o’clock, was for her husband; but somehow a premonition of the purport of the message it had been intended to give him, had he been at home, flashed across her mind. And so she dispatched a nephew down to the office in response to the message, remarking that she knew “something had happened to Charlie “ a few minutes afterwards she learned the sad story of his death from two gentlemen, who had been sent to break the news.

Chief Train Despatcher Duval, of the Booth system, having ascertained that the father of the dead boy, Mr. Charles. Hutchison, of 34 Kent street, was at Renfrew, communicated with him at once by wire so that he will be able to take the early morning train to Barry’s Bay, where the body of his son lies, awaiting the coroner’s inquest.

Relief Sent Promptly.

The run-off occurred at about 7.30, and at 9 o’clock word of the accident was briefly telegraphed to the train despatcher’s office here from Barry’s Bay. Measures were promptly taken to forward relief to the sufferers. A tool

Charles Hutchison was a bright young fellow, well thought of by his employers. He entered the service of Canada Atlantic about five years ago. Previously to that he was for a short time on the C.P.R. He was the nephew of Dr. Geo. Hutchison.

James Casselman, the brakeman, was the fourth of his family to perish in a railway accident, three brothers having been killed on the road at various periods during the past six or eight years. He was a married man, of 45 years of age, and lived with his wife and only daughter at 62 Cedar street.

William Russell had for some time been employed at the freight shed on Elgin street; but laterally was in charge of the store car. It was in this capacity that he went out yesterday morning with his car to distribute stores to the several stations along the line. He resided at 44 First avenue, and leaves a widow and two children but poorly provided for.

The remains of Casselman and Hutchison will be brought home to-day.

From the Eganville Enterprise, May 5, 1883

THE A & NW Ry. IN HARD LUCK: Two Smash-Ups in One Week.

The first accident to a passenger train on the Eganville Branch of the CPR took place yesterday (Monday.) The noon train which consisted of the engine and tender, two flat cars loaded with the alligator tug, “Bonnechere No. 1.” two freight cars, a baggage car and two passengers cars, had just passed the street leading to the bridge on its way to the station, when the wheels under the first freight car by some means became detached and coming against the wheels of the second freight car also detached them. The engine with the flat cars and the body of the first freight car, after it

Continued on page 14.

Continued from page 13.

became detached from the others, went on for some distance, the body of the car bumping along the ties and rails. The second freight car and baggage car went off the track toward the embankment. The passenger cars did not leave the rails. The first freight car, which was loaded with buggies for Mr. R. Reeves received comparatively little damage from its rough usage. The second freight car was badly smashed up and the baggage car was also considerably damaged. Fortunately the second freight car and the baggage car went off the track toward the embankment in rear of Mr. T. G. Boland’s house. Had they gone off towards the other side they would have gone down an embankment of twelve feet and might have dragged the passenger coaches after them. Fortunately no one was injured.

About nine o’clock on Thursday morning, the residents of the Plaunt section of Renfrew were startled by a report of cannon-like force. Hasty inspection showed there had been an accident of some sort on the CPR line - a large flat-car standing high in the air. It seems that the A. & N. - W. engine with a box-car attached was being shunted, and a line of flat-cars being obscured from the engineer’s view, he dashed his engine and car into them with considerable force. The brakes were on the flats and the first car of the line was simply doubled up like cardboard, the large timbers being snapped in half; and the iron-work being bent in all directions. The box-car was slightly damaged and the hind trucks forced off the rails. The damaged flat overhung the CPR main line, but was quickly pulled away from its dangerous position.

From the Ottawa Journal, February 28, 1908 A broken rail caused a run off and partial wreck this morning at Eganville Junction four miles west of Renfrew on the Canadian Pacific Railroad. The accident happened at 6.58 to train No. 96, known as the “Winnipeg” coming to Ottawa from the west in charge of Engineer B. Chapman of Ottawa and Conductor Ledkea of North Bay. --only injury was burns to the cook. More. The baggage car slid down the embankment and is standing on end and the mail car, dining car and sleeper were turned over on their side. The other four coaches simply left the track and are resting on the ties. -- The engine, No. 1113 was not damaged much.

EGANVILLE, Ont. Sept. 7 (Special) Three persons were killed, one is in critical condition and two others escaped with a shaking up when their automobile plowed into the engine of the CNR’s Ottawa to Barry’s Bay Special one mile east of here on Saturday afternoon.

- - -

The accident occurred at 5.30 Saturday afternoon when the slow moving train drawing five passenger-laden coaches, started to move to westward across Spring street crossing, one mile east of here on Highway No 41 between here and Matawachan.

The automobile, driven by Albert Kelly, crashed into the engine of the train and bounced several feet to land upright in a .wrecked condition. Engineer George Turner, of Hurdman’s Bridge at the controls of the CNR train, brought his locomotive to a stop less than 100 yards after the crash. Although a piston on the engine was broken, the train was able to continue its journey to Barry’s Bay. The conductor was William Swinwood. of 110 Clegg street, Ottawa

From the Ottawa Journal, February 8, 1904

A Canada Atlantic railway freight train consisting of 36 cars of logs in charge of Conductor Connelly which left Madawaska late Friday evening the 5th inst. for Ottawa jumped the rails near Killaloe station at 7.45 p.m.

The train was running at a moderate speed, when she suddenly left the rails, overturning 16 cars and the tender, which was almost completely demolished. Fortunately the engine did not go over, which greatly lessened the danger to the driver and fireman, although as it was they had a very close call. Driver H.H. Leggat, who stuck to his post, had enough presence of mind to shut off the steam as soon as he felt that something was wrong. He, however, strange to say, is the only one of the train hands that was hurt. He was thrown from his engine and falling backwards across an iron bar was considerably bruised about his back. Last evening he was resting nicely, and hoped to be out again in a short time.

As soon as word had reached the city a wrecking train was despatched to the scene.

From the Ottawa Journal, January 23, 1934 TRAIN IS DELAYED.

Motor trouble on the C.N.R. Madawaska-Pembroke-Ottawa train this morning as it was leaving the sheds at Madawaska caused it to be more than two hours late on arrival at Ottawa. Due at 10.55 a.m, it did not reach here until nearly two o’clock. Some difficulty was experienced in getting the engine off the turn-table at Madawaska with the result that a steam engine had to be commissioned to convey the passengers here.

From the Ottawa Journal, July 24, 189 AN INQUEST TONIGHT - An inquest will be held to-night over the remains of the late J.A. Bull of the O.A. and P.S. Ry., who died yesterday as a result of injuries sustained at Whitney Saturday.

- -UNDER THE WHEELS

JAMES A. BULL MANGLED BY A TRAIN Employee of the O.A. & P.S. Injured Saturday Night, and Died Yesterday

Derailments and collisions were common occurrences in the early days of rail travel. This is a collision on the Ottawa, Arnprior & Parry Sound line built and operated by J. R. Booth. Mattingly Image Collection, public domain photo

From the Ottawa Journal, September 2, 1925

Instantly killed by C. P. R. Train

Renfrew, Sept 2 - Struck By the C. P. R. Eganville passenger train at 11. 15 today, Charles Cochrane, 23 years old, employe of the Renfrew Machinery Company, was instantly killed. He felt sick while at work in the factory and decided to return to his boarding house. He was taking a shortcut across the tracks when he was killed. It is believed he tried to save himself too late, as only one foot was cut off. Cochran arrived in Canada from England last spring. He lived here with his brother, who came to Canada with him. An inquest will be held.

From the Ottawa Citizen, September 8, 1947

Three Die As Car Hits Train At Eganville

James A. Bull, of 19 Second avenue, a fireman on the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway, was so badly injured by being run over by a train at Whitney Saturday night that he died yesterday morning. While Mr. Bull was standing on the tender of his engine shortly after six o’clock Saturday night, filling the boiler of the locomotive with water, a shunting engine jolted against the rear end of the train to which the locomotive attended by Mr. Bull was attached.

Fell to the Track.

The collision caused the man to lose his balance and fall to the ground. The train, set in motion by the jolt, passed over him, cutting off his right arm and crushing his right leg. He was pulled out and taken to Ottawa in a special car. In spite of all that could be done for him, however, he passed away yesterday morning.

The late Mr. Bull was 20 years of age and lived at the residence of his father, Mr. Enoch Bull, foreman for S and H. Borbridge, trunk manufacturers. He was a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Trainmen. 9

-Source, Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages

ROBERT FISHER Staff Reporter

BARRY'S BAY – Is there still a train engine at the bottom of Carson Lake?

Was there ever a train engine at the bottom of Carson Lake? Or is it simply a matter of local lore not unlike the Loch Ness monster in Scotland or other mythical creatures and sightings?

Frank Burchat, who’s a member of the Carson Trout Lepine & Greenan Lakes Association (CLTG) said the question came up about six years ago at an association meeting.

“One of the main members of the association was asked a question whether or not the train was still in Carson Lake,” said Burchat.

Rumour and local legend has it that in 1909, Aug. 16 to be precise, a Grand Trunk Railroad train derailed passing the lake. Supposedly the engine, tender (coal car) and perhaps a couple flatbed cars went into the lake. Even that’s not certain though.

As the story goes, there was rain that washed out and loosened some of the track bed. The train derailed on the loose ground and slid down the hill into the lake. Newspaper clippings from the time confirm a derailment.

From the Renfrew Mercury Aug. 20, 1909: “There was a wreck on the Grand Trunk Railway on Monday through an unusual cause – a cloudburst. The accompanying torrent of rain rushing down a steep hillside undermined nearly a mile of track near Carson Lake…”

A local rail buff, Colin Churcher, told Wendy Wolak, another member of CLTG, that he had no information about a car that went into the lake.

“People thought it slid into the lake because it is very deep,” said Burchat. “At that end the slope goes down to 100 feet within several hundred feet of the shoreline.”

No information exists about whether a search was conducted for the rail cars. Wolak did some research and found that if the equipment could have been recovered, the railway would have done so.

With the question posed at the association meeting, the search was on. Burchat said the town told the association it would put up a historical plaque if evidence of the engine or any part of the train was found in the lake.

Burchat is a recreational diver. He dove the site several times and other recreational divers have, too.

“Never found anything,” Burchat said flatly. Rumours persisted, he said, from people in the area that divers had gone down, 25 to 30 years ago, and found a train. There is no evidence supporting these stories and no one has been able to contact the divers.

“At some point, someone told me they retrieved a teapot and some cutlery,” Burchat continued. He said that was possible because the engineer and fireman would be in the engine for long periods of time and would take meals while travelling.

“We’ve not found any of that stuff,” he said. “Couldn’t find the name of who may have retrieved it, couldn’t

find the names of the divers that claim they’ve seen something.”

Fast forward to 2023

This past August, some professional divers were brought in to search and an OPP search and recovery team that was working in the area also assisted in the search.

Local Kris Totosko searched the area and found nothing unusual on the lake bottom. He did notice an anomaly in one spot.

The OPP team was at the lake working on a missing person cold case of someone who was presumed drowned in the lake and were attempting to finally close the file.

The OPP dive team had side-scan sonar and shared some of their images of the area of the lake where the train was rumoured to be. No sign of a train or mechanical equipment turned up on the OPP sonar images. They did find something in approximately the same area as Totosko had.

A dive team of Wayne and daughter Samantha Gignac responded to a request for divers and made four dives in Carson Lake, including the area where the anomaly had been found.

Larger rocks, trees and branches is what they turned up. No train engine, tender or other evidence of rail

equipment in the water.

Going back to Churcher, he followed up with more information from searches of other local newspapers and found no evidence of a train in the lake.

“I have no record of a locomotive in Carson Lake in my listing of sunken locomotives,” he said in an email to Wolak.

“The logical explanation is it got taken out,” said Burchat. “If it was ever there at all.”

The human tragedy

William J. Thurston was the fireman on the train. His body was found crushed under a rail car at the site of the derailment. There’s no information about whether he was found on land or in the water.

There were stories in three local papers about Thurston. Apparently several of his family members worked in the rail industry, including brother John who was a station master at several stations including Barry’s Bay. Thurston’s niece Norma lives in Whitney. His grave is in the Catholic cemetery in Madawaska on Route 523 just south of Route 60.

A plaque dedicated to Thurston stands near the site of the derailment along the old rail line, now an ATV and snowmobile trail.

Ralph Pecoskie - Submitted by Ralph Pecoskie

The wheels were mighty big, hard looking discs. Being connected by thick, huge slabs of iron and every now and then the polished piston connecting to them moved slightly, hissing a sharp puff of steam. There was amazement registering in my mind as a young boy of five years or so in 1954. Standing at the station platform, early December, we waited to board a train, with my mother, travelling to Simpson’s Pit station to see my grandmother. That station, at Barry’s Bay was an adventure and smelled burnt.

Growing up four houses down from the tracks crossing Paugh Lake Street, we were connected to the railway. Sometimes up to 14 rail cars parked on the siding, as far down as Slim Coulas’s clothing store, provided time for young boys to run on top of the box cars, pull on the air release levers and play with the huge hose couplers. The station was a mighty hurried and mysterious place of activity.

Don Derraugh - Robert Fisher

Don Derraugh sent the short summary below. The Gazette spoke with him afterward to get some more detail on his reminiscences of the railroad. My father was a section foreman on this railway from 1941 to 1981. I have worked on the railway when some of the men took their holidays. The money was very good but the work was very laborious. I had to work hard for my money.

My sister and I would take the train at Golden Lake every Saturday to Killaloe and have our music lesson at the convent in Killaloe. My sister played the piano and I play the violin. We played at senior homes, legions, curling clubs and many special events. I can relate to a lot of stories about this experience. I have some of the old passes that we used to allow us to travel on the C. N. R. My father was section foreman from Golden Lake to Eganville, Golden Lake to Lake Dore, Golden Lake to Killaloe and for the last few years he was road master from Pembroke to Brent on the Pembroke line. He would get calls on the weekend to come and remove the cattle from the track if a train was coming. My father worked at Rock Lake in Algonquin Park on the C. N. R.

Derraugh said he began working as a vacation fill-in for summers when he was about 18. He thought it odd that the men would have on long underwear in the heat of summer. They told him, ‘It won’t be very long,’ and he would be wearing it, too. Sure enough, after a short time hauling creosote-coated railway ties, he joined the others in their long johns. “You get that creosote on you, boy, you know it. It burns like acid.”

Derraugh remembers riding on what they called the gas car along the main line to get from place to place. It was a gas-engine, motorized car that moved them along quickly. The older hand pump cars, he explained were used in rail yards where speed wasn’t as crucial. He did work with his father on occasion and didn’t get any special treatment for being the boss’s son. “For me it was pretty much slave labour,” he laughed. They worked in teams moving ties into place and he had to work as hard as everyone else otherwise the team would get