May/June 2022 • Vol. 91 • No. 3 Supporting Your Success 50 Years of Title IX In this issue: Thoughts on the Americans with Disabilities Act Navigating Same-Sex Parentage Cases

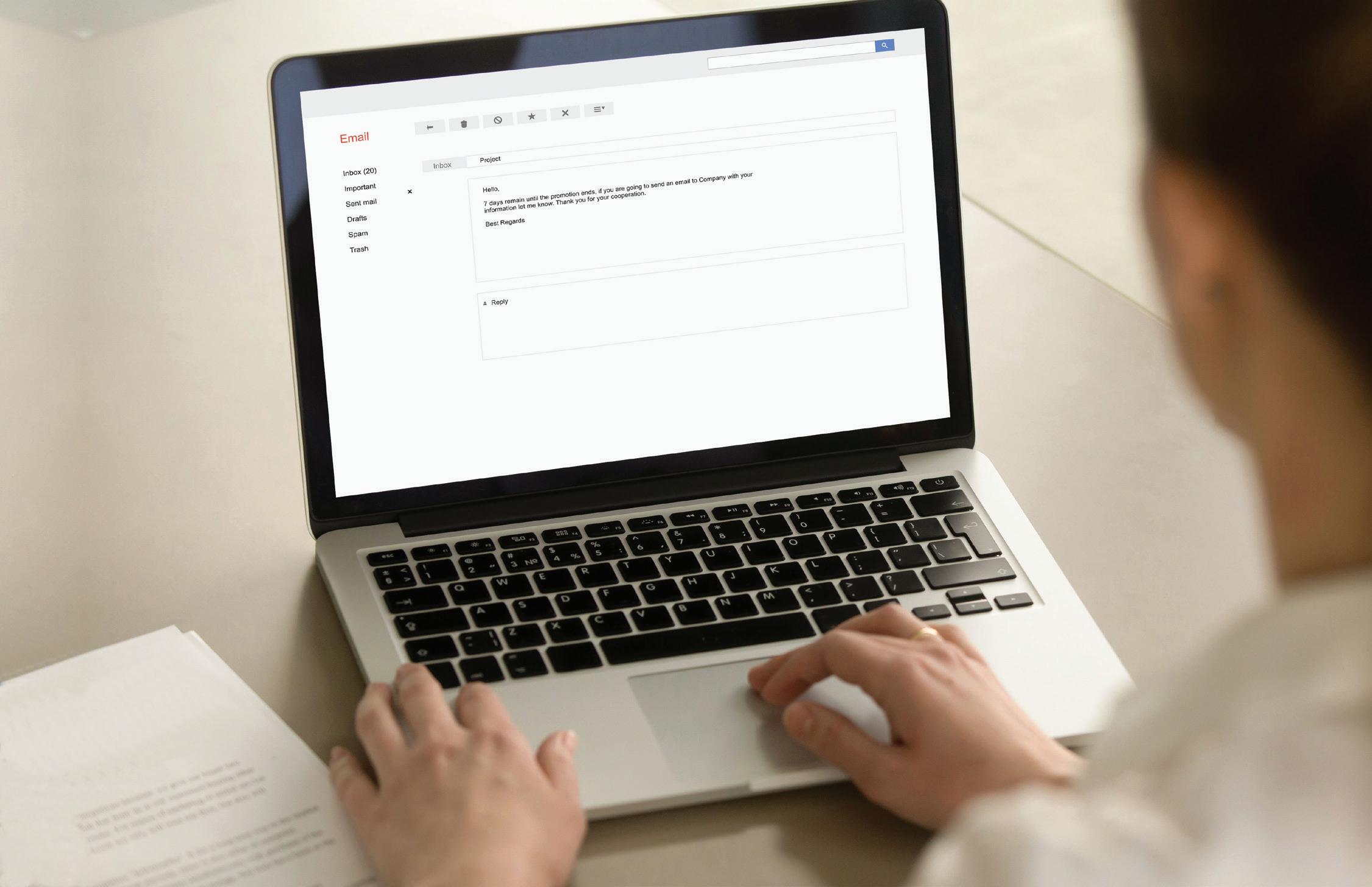

I love LawPay! I’m not sure why I waited so long to get it set up.

Trusted by 50,000 law firms, LawPay is a simple, secure solution that allows you to easily accept credit and eCheck payments online, in person, or through your favorite practice management tools.

Vetted and approved by all 50 state bars, 70+ local and specialty bars, the ABA, and the ALA

62% of bills sent online are paid in 24 hours

New Case Reference **** **** ****

*** Trust Payment

YOUR FIRM L OGO HERE PAY AT TO RNEY PO WE R ED BY

Get started at lawpay.com/ksbar 888-281-8915 TOTAL: $1,500.00

9995

IOLTA Deposit

22% increase in cash flow with online payments

Data based on an average of firm accounts receivables increases using online billing solutions. LawPay is a registered agent of Wells Fargo Bank N.A., Concord, CA, Synovus Bank, Columbus, GA., and Fifth Third Bank, N.A., Cincinnati, OH.

Law

+ Member Benefit

–

Firm in Ohio

Provider

4 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association FEATURES 18 Thoughts on the ADA as City of Cleburne Nears Forty By Scott Geroux 30 50 Years of Title IX: So Much More Than Sports By Ashley Rohleder-Webb 42 Navigating Same-Sex Parentage Cases By Valerie Moore 8 From the Kansas Bar Association President 10 From the Executive Director 12 Law Practice Management Tips & Tricks 14 Substance & Style 16 Law Students' Corner –University of Kansas School of Law 17 Animal Law Update 20 Kansas Mock Trial DEPARTMENTS 22 From the Disciplinary Administrator 26 From the KBA Media-Bar Committee 50 Members in the News 50 Classified Advertisements 51 Obituaries 52 Appellate Decisions 61 Appellate Practice Reminders 62 Advertisers Index contents

Jay Daugherty Mediation & Arbitration is pleased to announce that Bruce Keplinger, long recognized as one of Kansas and Missouri’s most outstanding civil trial lawyers, will be one of its mediators effective June 1, 2022. Mr. Keplinger has over 40 years of rich litigation experience and has first-chaired over 150 jury trials. He has also served as a civil mediator in numerous disputes as well as an arbitrator for the NASD and FINRA.

Bruce Keplinger is a Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers and is past president of the Kansas Association of Defense Counsel. He is rated as AV Pre-eminent by Martindale Hubbell and has been listed in Best Lawyers in America for over 25 years. Bruce was born and raised in Kansas, receiving his undergraduate degree from the University of Kansas and his law degree from SMU, and has spent his entire legal career practicing in Kansas and the KC metro area working primarily with the Kansas law firms Payne and Jones and for the last 20 years with the Overland Park firm Norris and Keplinger. He is admitted to all state and federal trial and appellate courts in Kansas and Missouri and was admitted to the United States Supreme Court in 1989. During his long career handling complex medical and legal issues, Bruce Keplinger has always focused on resolving disputes as swiftly and inexpensively as possible, viewing the trials that he has done as the last resort. As he enters the full-time practice of mediation and arbitration at Jay Daugherty Mediation & Arbitration, he looks forward to using his litigation and mediation training and skill to help resolve disputes across Kansas and in the Kansas City metro area.

“Our mediation goals extend beyond merely achieving a resolution of the case. Disputes are also about emotion. Mediation results should please clients and clients should leave the mediation with an enhanced regard for their attorneys.”

J ay D augherty & B ruce K eplinger

JAY DAUGHERTY MEDIATION & ARBITRATION

FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO SCHEDULE ONLINE, PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT: WWW.JAYDAUGHERTYMEDIATION.COM 4717 GRAND AVENUE SUITE 830 KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64112 816.931.6300 TEL

J ay D augherty M e D iation

JUDICIAL NEUTRALITY | RELENTLESS PASSION

B ruce K eplinger to J oin

& a r B itration

2021-22 Journal Board of Editors

Professor Emily Grant (Topeka), chair, emily.grant@washburn.edu

Sarah G. Briley (Wichita), sbriley@morrislaing.com

Richard L. Budden (Kansas City), rbudden@sjblaw.com

Kate Duncan Butler (Lawrence), kbutler@barberemerson.com

Boyd A. Byers (Wichita), bbyers@foulston.com

Lindsey Freihoff (Lenexa), lfreihoff@hinklaw.com

Connie S. Hamilton (Manhattan), jcham999@gmail.com

James Hampton (Topeka), jamesrichardhampton@gmail.com

Lauren G. Hughes (McPherson), lhughes@bwisecounsel.com

Michael T. Jilka (Lawrence), mjilka@jilkalaw.com

Lisa R. Jones (Ft. Myers, FL), ljones@fgcu.edu

Joslyn Kusiak (Independence), jkusiak@kellykusiaklaw.com

Casey R. Law (McPherson), claw@bwisecounsel.com

Deana Mead, Staff Liaison, dmead@ksbar.org

Professor John C. Peck (Lawrence), jpeck@ku.edu

Karen Renwick (Kansas City), krenwick@wrrsvlaw.com

Teresa M. Schreffler (Wichita), co-chair, tschreffler@gmail.com

Richard H. Seaton Sr. (Manhattan), seatonlaw@sbcglobal.net

Michael Sichter (Kansas City), msichter@wrrsvlaw.com

Richard D. Smith (Topeka), rich.smith@ag.ks.gov

Nicholas Trammell (Topeka), nicnassuet@gmail.com

Hon. Sarah E. Warner (Lenexa), warners@kscourts.org

Issaku Yamaashi (Overland Park), iyamaashi@foulston.com

The Journal Board of Editors is responsible for the selection and editing of all substantive legal articles that appear in The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association. The board reviews all article submissions during its bimonthly meetings (January, March, May, July, September, November). If an attorney would like to submit an article for consideration, please send a draft or outline to editor@ksbar.org.

2021-22 KBA Officers & Board of Governors

President

Cheryl Whelan, cwhelan@ksbar.org

President-Elect

Nancy Morales Gonzalez, nancygonzalezKBA@gmail.com

Vice President

Laura Ice, lauraice@textronfinancial.com

Secretary-Treasurer

Mark A. Dupree Sr., mdupree@wycokck.org

Immediate Past President

Charles E. Branson, cbranson@ksbar.org

Young Lawyers Section President

Rick K. Davis, rick@rickdavisrealestate.com

Immediate Past President

Katherine E. Marples Simpson, ksimspon@stevensbrand.com

District 1

Michael J. Fleming, mike@kapkewillerth.com

Katie A. McClaflin, kmcclaflin@mkmlawkc.com

Katherine S. Clevenger, katherine@pcfamilylaw.com

District 2

Bethany J. Roberts, broberts@barberemerson.com

District 3

Angela M. Meyer, angela@angelameyerlaw.com

District 4

Robert J. Lane, roblane.dml@gmail.com

District 5

Vincent Cox, vcox@cavlem.com

Terri J. Pemberton, tpemberton@cox.net

District 6

Laurel A. Michel Driskell, laurelmichel@kenberk.com

District 7

William L. Townsley, III, wtownsley@fleeson.com

Megan S. Monsour, mmonsour@hinklaw.com

Sara Zafar, sarazafar08@gmail.com

District 8

Dell Marie Shanahan Swearer, dell@hutchcf.org

District 9

Aaron L. Kite, aaron@kitelawfirm.com

District 10

Gregory A. Schwartz, gaschwartz@schwartzparklaw.com

District 11

Candice A. Alcaraz, calcaraz@wycokck.org

District 12

Alexander P. Aguilera, alex.aguilera@leggett.com

Bruce A. Ney, bn7429@att.com

John M. Shoemaker, john.shoemaker@butlersnow.com

At-Large Governor

Amanda L. Stanley, amanda.stanleyjd@gmail.com

KDJA Representative

Hon. Daniel D. Creitz, dcreitz@31jd.org

ABA Board of Governors

Linda S. Parks, parks@hitefanning.com

KBA Delegate to ABA House

Natalie G. Haag, nhaag@capfed.com

Eric K. Rosenblad, rosenblade@klsinc.org

ABA State Delegate

Rachael K. Pirner, rkpirner@twgfirm.com

YL Delegate to ABA House

Joslyn Kusiak, jkusiak@kellykusiaklaw.com

KBF Representative

Jeffery L. Carmichael, jcarmichael@morrislaing.com

Executive Director of the KBA/KBF

Stacey Harden, sharden@ksbar.org

OUR MISSION

The Kansas Bar Association is dedicated to advancing the professionalism and legal skills of lawyers, providing services to its members, serving the community through advocacy of public policy issues, encouraging public understanding of the law, and promoting the effective administration of our system of justice.

6 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association Published by Peterson Media Group, Topeka, KS, (785) 271-5801 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association (ISSN 022-8486) Volume No. 91 Issue No. 3, is published bi-monthly by Kansas Bar Association, 1200 SW Harrison Street, Topeka, KS 66612. Periodicals postage paid at Topeka, KS and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association, PO Box 751080, Topeka, KS 66675-1080. Phone: (785) 234-5696; Fax: (785) 234-3813. Member subscription is $25 a year, which is included in annual dues. Nonmember subscription rate is $45 a year. The Kansas Bar Association and the members of the Board of Editors assume no responsibility for any opinion or statement of fact in the substantive legal articles published in The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association. Copyright © 2022 Kansas Bar Association, Topeka, Kan. For display advertising information, contact Blake Peterson at (785) 271-5801 or email blake@petersonmg.com. For classified advertising information, call (785) 234-5696 or email editor@ksbar.org. Publication of advertisements is not to be deemed an endorsement of any product or service advertised unless otherwise indicated.

Kansans Need YOU

Become a Kansas Bar Foundation Fellow

You can become a Fellow online or through the mail. For more infor mation on the Fellows Giving Program, visit www.ksbar.org or contact Stacey Harden at sharden@ @ksbar.org.

The Kansas Bar Foundation:

increases access to legal services for underserved communities

helps promote access to justice for all Kansans

administers IOLTA funds benefitting organizations that provide civil legal services and the administration of justice to Kansans

supports law school student scholarships

provides education to the public on the law, including civics education

Already a Fellow? Thank you!

Please consider a higher level of giving.

Give back and lend a helping hand TODAY!

KBA’s Pillars of Professionalism and Ethical Obligations Face a New Working Environment

By Cheryl Whelan, KBA President 2021-2022

The Kansas Bar Association adopted the Pillars of Professionalism in 2012 and the Kansas Supreme Court and the Federal Courts of Kansas soon followed. In addition, to the ethical duties contained in the Kansas Rules of Professional Conduct, attorneys also have a duty of professionalism. Although the Pillars are aspirational instead of mandatory, the adoption of the Pillars by courts sends a strong signal regarding expectations of professionalism. We are members of an honorable profession. As the Pillars states, we “have a duty to perform [our] work professionally by behaving in a manner that reflects the best legal traditions, with civility, courtesy, and consideration.”

Although the Pillars focus on professionalism, the Pillars are, in many ways, tied to our ethical responsibilities. For example, Pillar VI requires us to “[b]e courteous, respectful, and considerate. If the opposing counsel or party behaves unprofessionally, do not reciprocate.” Pillar VII requires us to “[b]e prepared on substantive, procedural, and ethical issues involved in the representation.”

When the Pillars were developed and adopted 10 years ago, attorneys practiced in a much different environment than they do now. In the last 10 years, digital transformation occurred and continues to occur at what seems to be a faster pace. Using technology to increase efficiency in the practice of law raised ethical issues, such as cybersecurity, that as a profession we continue to address. But for the eight years after the Pillars were adopted, the increasing use of technology did not significantly change the interactions that we had or how we interacted. Our interactions with other attorneys, the courts and clients still occurred in person. We gathered in person for continuing legal education seminars and networked in person.

The pandemic changed all of that. Suddenly, for many industries including the practice of law, remote work became the norm. Attorneys started working virtually from home. Courts operated virtually as much as possible. In-person CLEs were cancelled and virtual CLEs became accepted and normal. A recent KBA membership survey found that most KBA members will only travel 60 miles to attend a CLE. I assume that is because of the convenience of remaining in the office and decreased travel time.

I recently talked with a friend who is a senior partner in a law firm. Our conversation was the genesis of this column because he talked about the firm’s difficult decision on remote work policies. Should work be 100% remote, 100% in the office or some sort of combination? Studies have shown that many employees prefer remote work. Although technology allows us to work remotely 100% of the time, remote work raises many concerns. The 2021 American Bar Association’s Profile of the Legal Profession found that “[a]lmost half of lawyers felt disengaged from their employer during the pandemic and overwhelmed by all they had to do. Again, this was especially true for women and lawyers of color.”

My concern about virtual work is the professional development of the newest members of our profession. My first attorney job was with the Kansas Court of Appeals where I served for five years as a research attorney and the motions attorney. The

8 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association

from the kansas bar association president

experience of working with the judges who mentored me, and the other attorneys shaped my approach to the practice of law. The personal interactions, especially with the judges, educated me about substantive, procedural and ethical issues. The advantages of collaborating with the attorney in the next office or with a judge about a legal issue cannot be overstated. Even 30 years later, when I am unsure how to address a legal issue or want to talk through the legal analysis of an issue, I still walk down the hall and talk with other attorneys or law clerks. Our law clerks have been surprised by how helpful these conversations are. Several months ago, a law clerk and I had several lengthy conversations about a jurisdictional issue. He learned, I learned, and we figured it out. These spontaneous conversations, collaboration and mentoring cannot be easily duplicated in a remote work environment.

The American Bar Association addressed some of these issues in Formal Opinion 498 (issued March 10, 2021) which addresses the challenges associated with the virtual practice of law. The opinion focuses on the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct and the commonly implicated model rules including competence, diligence, communication and supervision. These ethical obligations are similar to our professional obligations as described in Pillar VII. How do supervisory attorneys supervise their subordinate attorneys in their professional and ethical obligations? What policies and procedures have been put in place to ensure that the work environment is consistent with our professional and ethical obligations? How do we assist the newer members of our profession with their professional development?

There are no easy answers to these questions, and I certainly do not have the answers. As we work together to figure this out, we must be aware that the desire to work remotely cannot overshadow our obligations to the newest members of our profession. Spontaneous conversations, collaboration and mentoring are just as important to our profession as they were pre-pandemic and are important in the role we play in our society. u

As the Pillars states, we “have a duty to perform [our] work professionally by behaving in a manner that reflects the best legal traditions, with civility, courtesy, and consideration.”

Cheryl Whelan is the President of the Kansas Bar Association. Whelan is the Director of the Kansas Office of Administrative Hearings. Before assuming that role, Whelan served as an Assistant Attorney General and the Director of Open Government Training and Compliance in the office of the Kansas Attorney General. She has many years of experience as an attorney with various governmental agencies including service in the Army Reserve Components. A long-time active member of the KBA, Whelan has served on the Executive Committee of the Board of Governors, the Commission on Professionalism, the Annual Meeting Planning Committee, the Board of Publishers, the Law Related Education Committee, the Media-Bar Committee, the Nominating Committee and the Public Information Committee.

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 9

Procrastination –New Achievement Unlocked!

By Stacey Harden, Executive Director, KBA/KBF

“I never put off till tomorrow what I can do the day after.” Oscar Wilde

Ispent more than a few days, or maybe even weeks, pondering what to write about in this issue. Well, sort of … it might be more accurate to say that I thought about writing my column, realized I had days left built into the schedule, and then decided a handful of days past the internal deadline (which is coincidentally on the day of the “drop dead” deadline) that I should probably start thinking about what to write. And it came to me – the fine art of procrastination.

But what exactly does procrastination mean? According to the Britannica Dictionary, procrastination is defined as “to be slow or late about doing something that should be done: to delay doing something until a later time because you do not want to do it, because you are lazy, etc.” Ouch. That sounds so … harsh.

I know what procrastination looks like for me – delaying something that can easily be done today, but the due date isn’t for two more weeks, so I work on something else or binge-watch three seasons of a program in one weekend or find anything else to do. I don’t delay to the point of missing hard deadlines, but I do blow past the soft deadlines with a speed like the Kansas wind in April. I rationalize this perfectly in my mind by convincing myself that I do all my best work when under pressure. Because, well, I have always been this way. Yet the hard deadlines in my life, primarily at home, are all coming due in May, and I am starting to feel the pressure. My youngest son graduates in two weeks (and nope – I don’t even have party decorations purchased yet); I am merging households with my soon-to-be husband and haven’t packed a single box; we have two kids coming home from college and, you guessed it, I have not made any arrangements about how to physically move them home or make space for them in a newly merged household. I have known about all of these things for months (some might point out it’s been years), and here I am, literally days away and yet, I am no closer to being prepared for these things than I was when the calendar flipped to 2022. Master Procrastination Achievement unlocked!

But enough about me and my procrastination – if you are a procrastinator, regardless of your level, and maybe you are looking at the June 30 CLE compliance deadline, the KBA is here for you. Check out our CLE offerings in June and the super easy and slick On-Demand All Access Pass. You can get all 12 of the required hours when it works best for you, over the course of a weekend, a week, or a month – whatever fits your procrastination achievement profile. No pressure, no judgment, just achievement! You do you! The KBA is here to help! Even if you are not a fellow procrastinator, please check out the KBA’s CLE offerings this summer. We have some stellar programs lined up that you may be able to roll over to the next year.

And if you have the time, check in on us master procrastinators. If you don’t get to it until the day after tomorrow, don’t worry –we get it! u

Stacey Harden joined the KBA in the fall of 2019 as the Accounting and Finance Manager before becoming Executive Director in August 2020. Harden attended Baker University where she earned a bachelor’s degree in business, with an emphasis in accounting, as well as a master’s degree in business administration.

sharden@ksbar.org

10 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association

from the executive director

Where Does the Money Go?

Our designated charities for 2022 are:

CASA (Johnson/Wyandotte County)

Safehome and Hope House (domestic violence programs)

Metropolitan Organization to Counter Sexual Assault (MOCSA)

Kansas Bar Foundation

FosterAdopt Connect

In addition, we will fund Ethics for Good scholarships to each of the KU, Washburn and UMKC law schools and the Johnson County Community College paralegal program.

Stan Davis: Ethics for Good Elder Statesman

How Do We Sign Up for this Amazing, Funny, and Informative Program?

For a mere $90, you get both the ethics and the good, the entire Ethics for Good - now in its 23rd year!

6/22/2022 VIRTUAL - Register online at:

www.ksbar.org/event/EthicsforGood23

6/24/2022 IN-PERSON - Pre-paid registration required online at: www.ksbar.org/event/EthicsforGood23ip Who Are These Intrepid Performers?

Jim Griffin: Scharnhorst Ast Kennard Griffin, P.C.

Mark Hinderks: Stinson LLP

Todd LaSala: Stinson LLP

Steve Leben: University of Missouri - Kansas City

Hon. Jacy Hurst: Kansas Court of Appeals

Todd Ruskamp: Shook, Hardy & Bacon L.L.P.

Hon. Melissa Standridge: Kansas Supreme Court Ethics

CLE meets humor for good!

Pending 2.0 ethics hours in Kansas & Missouri

Questions?

Deana Mead KBA Associate Executive Director 785-861-8839 dmead@ksbar.org WATCH, LEARN, AND LAUG H FROM THE COMFORT O F YOUR FAVORITE CHAIR ! W EDNE S DA Y JU NE 22N D 11 A. M.– 12:40 P. M. TWO GREAT SHOWING OPTIONS! JOIN US AT JOHNSON COUNT Y COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOR A LIVE PERFORMANCE ! FR IDA Y JU NE 24 T H 2–3:40 P. M. VIRTUAL & IN-PERSON

IN-PERSON - Pre-paid registration required online at: www.ksbar.org/event/EthicsforGood23ip

Contact:

6/24/2022

- Register

www.ksbar.org/event/EthicsforGood23

6/22/2022 VIRTUAL

online at:

JCCC Foundation hosted reception

Understanding Our Judiciary’s Privacy in the Digital World

By Larry N. Zimmerman

Privacy in the Digital Age

KRPC 1.1, Comment 8 “To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology ….”

Monitoring relevant technology can require lawyers to be aware of a constant barrage of new information. Worrisome trends and legal issues can pop up in a variety of places –including salacious and titillating judicial conduct cases. In particular, Kansas lawyers should acquaint themselves with the opinion and oral arguments from In the Matter of Marty K. Clark, No. 123,911 (January, 2022).

Case Overview: Clark

Clark was a non-lawyer district magistrate judge of the 20th Judicial District. He and his wife were subscribers to a website described as “an online community for swingers.” Clark exchanged sexually explicit images and messages with another subscriber couple using the site’s private messaging. Clark never met the couple in person to consummate a physical relationship but the husband of the couple apparently grew dissatisfied with the attention to his wife and complained to the Kansas Commission on Judicial Conduct.

Stipulated Facts – Private Communications

Clark ultimately resigns, raises no exceptions to the Panel’s findings, and the whole case just stumbles into a public censure. Along the way, however, a hugely interesting and deeply disturbing discussion of internet privacy arises. The case does not resolve those issues but sounds a giant klaxon for lawyers who need to understand what the ethics system may not.

Two stipulated facts to the Panel:

• “The photographs included in Exhibit B were not available to be viewed by all [website] subscribers and were not available to the general public.”

• “[Clark] had to designate who had permission to access and view the photos.”

These stipulated facts establish that the website was private

requiring a subscription to access, not accessible to the general public, and Clark had to affirmatively designate which fellow subscribers could view his photos. Those facts describe something quite different than wide-open, generally viewable posts on social media like Twitter, Instagram, or even a law firm’s blog. In fact, the site described is not all that different from how a law firm’s client portal or a cloud-based case management system might work.

All Private Communications are Public?

The Panel significantly alters those stipulated facts in its Findings of Fact accepted by the Kansas Supreme Court. Finding 6 says, “The parties stipulated that the sexually revealing photographs were not available to be viewed by any [website] subscriber without permission from [Clark]. He also claims the photographs were not available to the general public. However, as with any social media posting, the photographs could be disseminated to the general public once they are released [emphasis added].”

The Hearing Panel explains later in its decision, “When [Clark] opened the door by releasing the photos to even one person [emphasis added] on this social media website, those photos could be generally disseminated to the social media world….”

This is a rather dramatic reinterpretation of social media. Justice Stegall engaged the Panel’s point at oral argument saying, “I’m wondering if that’s even right as a matter of law because that standard suggests that there’s no such thing as privacy at all in any two-way communication. So every email I’ve ever sent, every text message I’ve ever sent is now public. I don’t know how we escape that conclusion from the Panel’s conclusion.”

He continued, “What if I just say, ‘I’ll meet you for lunch at 12 PM…’ and I send that to whomever in a private text or email. According to the Panel’s findings, that email is public, right?”

The Examiner, Todd Thompson, responded less concerned about the policy precedent he was seeking than the graphically sexual nature of the images involved in the

12 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association law practice management tips & tricks

messages to which Justice Stegall replied, “It seems to me content of the communication cannot play a role in deciding if it’s private or public.”

The questioning from Justices Standridge and Biles at oral argument seemed to hint at some fundamental foreseeability in communicating via “social media” no matter the efforts taken to limit the recipient. The mere fact that you are communicating on social media is enough to trigger the feasibility that your communications might be shared. Again, however, the discussion of social media by both justices appeared to analogize to something open to the public like Twitter or Instagram. Neither seemed to distinguish between such public sites and a closed, subscription-based, private website. Is a law firm’s client portal on MyCase or Clio a social media site? Are private communications there between lawyer and client public because any post on social media may be foreseeably captured and made public?

A Problematic Case

On one hand, Clark is not a very significant case. The judge had retired before discipline, is not a lawyer and has not expressed an intent to run for his judicial seat again. Further, he took no exception to the quite exceptional Hearing Panel

report so vital issues were abandoned. Some would even argue that a judicial discipline case is irrelevant to lawyers.

However, Clark does provide a rather informative view into our judiciary’s understanding of privacy in the digital world. We do not know exactly what a “social media site” might actually be but we are on notice that the interpretation of that phrase might be exceptionally broad and protections for privacy and confidentiality under that broad umbrella might be scant. u

Larry N. Zimmerman is a partner at Zimmerman & Zimmerman P.A. in Topeka and former adjunct professor, teaching law and technology at Washburn University School of Law. He is one of the founding members of the KBA Law Practice Management Committee.

kslpm@larryzimmerman.com

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 13

Attend the #1 conference for attorneys October 10-11, 2022 Nashville, TN Learn more at cliocloudconference.com

Legal Writing Criticism, Roadblocks and Motivations

By Emily Grant

Are Lawyers Bad Writers?

I hope when you read this column title, you instinctively – and indignantly –responded, “no, we’re not!” Good for you. That was a test.

Though… and I hate to be the one to say it… perhaps there’s a reason many bar association journals, including this one, have a column devoted to good legal writing.1 There is a perception, both inside and outside the profession, that lawyers are terrible writers.2 And the complaint is not entirely new.3

Despite the age-old criticisms of lawyerly communication, the profession finds itself at a bit of a crossroads today in terms of identity and expectations for our writing. Today’s senior partners developed their communications style at a time when even intraoffice memos were drafted by hand or dictation, typed by someone else, proofread and then handdelivered.4 Now, that same message is transmitted in seconds via email, or heaven forbid text. So lawyers are operating in a profession that has almost anachronistic standards of formality and precision, but in a time when people expect a constant flow of communications.

last 200 years (not counting the English cases that pre-date our American legal system). Many of those opinions are dense and filled with archaic language. They’re difficult to read and even harder to understand. And after marinating in that writing for three years, it is not surprising that many lawyers-to-be begin to mirror that style such that the “traditional” legal writing found in casebooks becomes normalized and carried into practice.

The Lure of Legalese

While we might quibble with the motivations behind some of the criticism of our writing prowess, we have to admit that for a profession that makes its living with words, lawyers sometimes neglect to consider how or why their writing might be improved.

But it’s not because we’re lazy or bad at our jobs. We’ve come by our less-than-optimal writing skills honestly. And frankly, it likely started in law school (yes, I’m looking at myself and my colleagues in the legal academy).

Traditional Training

Law students almost exclusively read case opinions from the

Lawyers also often resort to legalese – stereotypical outdated “lawyer-sounding” words like herein and wherewith and party of the first part. My first semester teaching, I was explaining to my class why they should avoid legalese, and one student said “I came to law school to sound smart, and now you’re telling me I don’t get to use those words?”

Legalese can (sort of) have that effect, and it’s tempting to hide behind it out of professional insecurity.5 But it makes writing more difficult to parse. I do acknowledge that the law is complex and sometimes law-specific words (jargon, if you will) are necessary. But writing can (and should) still be readable and understandable, even when discussing difficult or abstract concepts.

14 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association substance & style

Audience Assumptions

Another reason legal writing can suffer is that lawyers sometimes write as though everyone else is an attorney. Sometimes the audience of your writing will be. But sometimes not. And even if the reader is a lawyer, they may not know what you know about a specific topic. The curse of expertise may cause lawyers to write as if everyone shares the same background knowledge and information.6 If they don’t, the writing will be difficult to absorb.

Persnickety Precision

Sometimes attorneys have to write for precision and, in so doing, may sacrifice readability. If there’s a chance a document will be negotiated or heavily scrutinized later, it makes sense that a writer will spend more time being precise and thorough, writing everything two (2) times, rather than focusing on being concise.7

Template Tracking

The use of document templates or forms, while necessary to efficient law practice, may perpetuate some bad writing habits. Once a merger agreement or standard of review paragraph or 12(b)(6) motion has been created (and successfully used), the incentives to rework the writing to make it sound better are low.8

Goofs from the Grind

Finally, sometimes we write poorly or carelessly because we are busy. We are overworked, with a six-minute billing clock running and a to-do list growing by the hour. Clients and supervising attorneys may expect instantaneous updates and responses. And so it is easy to stop caring about accessible, concise writing and instead just focus on getting the words on the page and the document delivered.

All of these factors may influence the overall impression of writing in our profession (and the copious “lawyers are bad

writers” jokes that permeate the internet). They’re certainly all understandable. And overcomable. u

References

Emily Grant has chosen a career path designed to help soon-to-be attorneys improve their legal writing skills. She teaches at Washburn University School of Law, and she can be reached at emily. grant@washburn.edu.

1. To be fair, I assume many other professional journals have similar columns; lawyers have not cornered the market on inaccessible writing.

2. See, e.g., Bryan A. Garner, Why lawyers can’t write, ABA J., Mar. 1, 2013; Jonathan D. Glater, A Bad Writer? Or Just a Lawyer?, N.Y. Times, Oct. 16, 2005.

3. Steven Start, Why Lawyers Can’t Write, 96 Harv. L. Rev. 1389 (1984).

4. Within living memory, the workday began when the office mail arrived at 9:00 or 10:00 a.m. One would spend an hour or so catching up on correspondence, have a smoke break, respond to a few messages, and then go out for a civilized lunch with colleagues. We used to be a proper country.

5. Yuriy Moshes, Bad Legal Writing Explained and Tips for Legal Writing, https://mosheslaw.com/bad-legal-writing-explainedand-tips-for-legal-writing/

6. Erica Toews, Is the practice of law turning us into bad writers?, https://www.toewslegal.com/blog/2018/12/2/is-the-practice-oflaw-turning-us-into-bad-writers

7. Richard James, Common Terrible Writing Habits Many Lawyers Develop–and How to Fix Them, https://therichardjames.com/ common-terrible-writing-habits-many-lawyers-develop-andhow-to-fix-them/

8. For an analysis of the risks of overreliance on transactional forms, for example, see William E. Foster & Andrew L. Lawson, When to Praise the Machine: The Promise and Perils of Automated Transactional Drafting, 69 S.C. L. Rev. 597 (2018).

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 15

KLH CONSULTING 316 26 5 58 00 Services include: • Oil and Gas Valuation and Appraisal • Estate Valuations • Royalty interest • Acquisitions • Economic Analysis www.klhoilandgasconsulting.com Licensed Petroleum Engineer

A Reluctant Lawyer

By James T. Schmidt Jr.

Unlike many who have dreamt of becoming a lawyer their whole life, I never desired to do so. It was not until a year or so into what I thought would be my career that I had that realization. In fact, I tried to do just about anything I could do to avoid law school, yet after years of avoiding law school, it became inevitable. I first considered going to law school during my junior year of college. I ordered an LSAT prep book and never opened it. I could not bear the thought of spending three more years in school without making money and beginning my life.

I have had an interest in politics and government since high school. In pursuit of those interests, I interned for Senator Jerry Moran and the Kansas House of Representatives while at Kansas State University. After graduation, I worked as a legislative staffer for Senator Jerry Moran in Washington, D.C. In that role, I advised Senator Moran on issues related to the Department of Justice, judicial nominations and other areas and corresponded with constituents on those issues.

After spending about a year in D.C., I realized I did not want to spend the rest of my career on Capitol Hill, and I began to consider ways to expand my marketability to employers. I considered attending night classes to get an MBA or a master’s in public policy. I did not want to go to law school because I knew it would be hard, and if I were to do it, I would do it full time, and I did not want to leave my job.

My direct superiors throughout my time in Senator Moran’s office were lawyers. I grew to respect their intelligence and unique way of looking at issues. I especially appreciated how any time I felt I had an issue figured out, they would offer up something that I had not considered. Through their mentorship, I fully bought into going to law school. The decision to go to KU Law was an easy one for me. As a

My decision to go to law school has paid off in more ways than I can count, and I thank all those who helped guide me here.

K-State undergrad, most of my friends resided in the area, and Senator Moran is a KU Law alumnus himself. Although, I still solely root for the Wildcats in sports.

Although I was leaving Washington, I knew I had a desire to continue pursuing my interest in politics and public policy. To that end, I have taken a handful of policy-related classes during law school. One such class was “Legislative Simulation and Study.” This class is a semester-long simulation of the Kansas Senate, where each student is assigned a legislator profile and must work for the benefit of their constituents. I was assigned the profile of a legislator who could not have been further apart from my actual political beliefs. I ran for and won the Senate Majority Leader position for the class; therefore, I was in charge of pushing forward our party’s agenda, an agenda this is typically contrary to my actual beliefs. It is in these sorts of roles where our minds expand the most.

I was selected my 2L year to be a Staff Editor for the Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy and Managing Editor as a 3L. My time with the Journal further allowed me to see diverse viewpoints. Being a public policy journal, we publish the viewpoints of a wide array of scholars, providing even more variation of thought to the legal community. As lawyers, many of us will lead the next generation, and it is ever important in this divided world to know and understand opposing viewpoints. KU Law has provided many opportunities for me to do this. In doing so, I do not doubt that I will be a leader and lawyer fit for the future. As President James Monroe said, “it is by a thorough knowledge of the whole subject that [people] are enabled to judge correctly of the past and to give a proper direction to the future.” My decision to go to law school has paid off in more ways than I can count, and I thank all those who helped guide me here. u

James Schmidt is a 3L at the University of Kansas School of Law from Houston, Texas. He received a Bachelor of Science in Journalism and Mass Communications from Kansas State University. He currently serves as Managing Editor of the Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy and as a student ambassador.

16 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association law students' corner – university of kansas school of law

State of Breed Specific Legislation in Kansas: An Update

By Katie Bray Barnett

Since publication of the January/February 2022 Kansas Bar Journal issue highlighting animal law, a handful of Kansas cities have reexamined their ordinances banning dogs by breed or appearance. In late 2021, the City of Overland Park repealed its 33-year-old ordinance banning “pit bull” looking dogs. After over a year of discussion with a panel of subject matter experts, input from its animal control officers, a public survey and discussion at multiple public safety committee meetings, city council unanimously voted to move away from the breed-specific language in a desire to approach dog behavior uniformly and target the cause of dangerous dog behavior.1 Then in January 2022, a criminal case on appeal from municipal court successfully challenged the constitutionality of the City of Leawood’s pit bull ban in Johnson County District Court. Dog owner Kristi Bond’s attorneys presented the testimony of several highly qualified experts, including a certified animal behaviorist, a veterinarian with experience in shelter medicine and purpose-bred canine genetics and a former Kansas Public Health Veterinarian, who each testified: (1. No one, not even experts, can reliably determine a dog’s breed by its appearance, (2. No breed of dog is inherently aggressive or dangerous, and (3. Breed-specific ordinances do not promote the safety and welfare of the public. Ultimately, the Court found the “dangerous animal” definition was unconstitutionally vague on its face, and as it was applied to the dog in the case, Lucy. This violated Ms. Bond’s 14th Amendment Procedural Due Process right because the Leawood ordinance had no objective standards to prevent arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement. The Court also noted that Leawood is one of the few remaining major cities in the Kansas City area with a pit bull ban, highlighting an overwhelming number of cities had repealed similar breedspecific language.2 The City of Leawood has since revised its ordinance in an attempt to cure the constitutional defect, but still bans “any dog having the appearance and characteristics of being predominantly of the breeds known as Staffordshire Bull Terrier, American Staffordshire Terrier, or American Pit Bull Terrier.”3 The cities of Abilene and Parsons have also repealed their pit bull bans in 2022.4 u

Katie Bray Barnett graduated from Missouri State University and received her Juris Doctor from the University of Kansas School of Law. She was awarded the Walter Hiersteiner Outstanding Service Award by the law school faculty, which is given to the student whose service to her fellow students, university, and community demonstrates the greatest promise for contribution to the legal profession and to society. Katie is the Founder of the KU Student Animal Legal Defense Fund, Founded the Animal Cruelty Prosecution Clinic and worked as a legislative attorney for Best Friends Animal Society before opening her own law practice. Katie’s legal practice consists of animal law, municipal law, law enforcement training on animals and legislative action. Barnett Law Office is the only practice in the state dedicated to animal issues. Katie is a vice-chair of the Animal Law Committee of the American Bar Association and has authored two American Bar Association Resolutions focusing on animal law. She has authored several journals and law review articles on animal law and assisted in drafting the International Municipal Lawyers Association’s dangerous dog model ordinance. Katie lives in Lawrence, Kansas, with her husband, two daughters and a house full of dogs.

References

1. City of Overland Park Public Safety Committee Minutes, September 9, 2022 (citing the desire to approach dog behavior uniformly and target the cause of dangerous dog behavior).

2. City of Leawood v. Bond, No. 20-CR-2516, Order Granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss (2022).

3. Leawood, KS, City Code § 2-102(k).

4. https://www.parsonssun.com/news/article_61cb4ece-468b11ec-bd66-2fccc8037818.html; http://www.abilene-rc. com/news/abilene-city-commissioners-vote-to-lift-pitbullordinance/article_a627f3d4-5cec-11ec-b242-bbb232b0dd5f. html (last accessed April 14, 2022).

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 17 animal law update

Thoughts on the ADA as City of Cleburne Nears Forty

By Scott Geroux

Scott Geroux is the 2022 winner of the Kansas Bar Foundation’s Capitol Federal Diversity Scholarship.

The Americans with Disability Act of 1990 can create mixed emotions among disability-rights advocates. On the one hand, the ADA has opened remarkable doors for individuals with physical and cognitive limitations. Physical structures changed; workplaces and schools shifted their policies toward accommodation. But the path toward equity is slow and ADA enforcement lawsuits can sometimes feel like a game of whack amole. One instance of discriminatory behavior might be stopped, but there is always another hill to climb.

Many of the current problems with the ADA’s antidiscrimination framework trace back to a case called, City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr. 1 In Cleburne, a non-profit sought to open a group home for individuals with cognitive limitations. The City of Cleburne opposed such a facility and stymied the non-profit’s efforts using zoning restrictions. The United States Supreme Court found the City’s denial reflected an unreasonable prejudice toward individuals with cognitive impairments. But this victory came with a catch. While the City had acted unreasonably in this case, the Court also ruled that individuals with physical and cognitive limitations are not a quasi-suspect class for purposes of Equal Protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. As such, the test for future discriminatory conduct would be the rational basis test.

Partially in response to City of Cleburne, Congress passed the Americans with Disability Act of 1990. A lot has changed since City of Cleburne, but its underlying test has not. As a result, the ADA continues to face constitutional challenges to the scope of the rights intended by Congress. Laws which discriminate against disabled persons will be upheld unless deemed irrational and ADA legislation designed to protect vulnerable citizens is throttled by strict judicial scrutiny of its application.

For example, ADA Title I provisions that authorize private employment discrimination suits against state governments are unconstitutional. Bd. of Trs. v. Garrett (2001). A somewhat prophetic minority opinion in Garrett acknowledged findings

that more than two-thirds of disabled individuals between 16 and 64 are out of the workforce even though they are willing and able to work. The frustrating reality of ADA lawsuits is that advocates may need to come back again and again in pursuit of equity.

One area where this dynamic of slow progress is felt is the world of legal education. The first major hurdle that prospective lawyers with physical or cognitive limitations face is the LSAC. The LSAC is critically tied to both law school admissions and most scholarships. But the test was not designed with persons with disabilities in mind.

The organization behind the LSAC, the Law School Admission Counsel (LSAC), has been sued several times over violations of the ADA’s accommodation and accessibility requirements.2 In 2014, the Department of Justice intervened in an action against the LSAC by LSAT test-takers for such violations. The LSAC entered a consent decree with the agency acknowledging widespread and systemic practices of discrimination against disabled law school applicants, paid $7.73MM in penalties and damages, and agreed to future reforms. Notably, much of the crux of the penalty came from violations against visually impaired and blind test-takers.

At a young age, I was diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disorder. As a non-traditional, legally blind LSAT test-taker in 2014 and 2015, I faced many unfair requirements to process my accommodation request, such as needing to provide technical documentation of why accessibility software requires the use of a computer mouse. The process of taking the LSAT twice to overcome accommodation challenges, and then being denied a seat for a third attempt when prior approved accommodations were changed without time to appeal those changes, presented a level of willful unfairness that I had not experienced previously.

Upon settling for a score that was compromised by the testing process, I attended law school for the first time in 2016. The school refused accommodation and I withdrew in principle with two weeks remaining in the second semester at a cost of 15 academic credits and $50,000. During the exit interview, the

18 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association diversity corner

The important message here is that reasonable accommodation does not create an advantage for disabled students and it does not level the playing field.

Dean of Student Affairs conceded that active obstruction of my legal education “had been going on since day one and I was too late to stop it.” At the time, I had received A and B grades on the written work that formed 70% of the final class grade.

In January 2020, I returned to law school at Washburn, and the proof is in the pudding. It has been the greatest experience of my life, and I cannot say enough about the dedication, professionalism and collegial environment that has fostered academic success. In 1967, my family was told that their three-year-old son would be sightless by age 18 and they responded with tough love. That prediction was not realized as I retain some vision many years later and I am grateful that my parents threw me into the deep end of the pool. Washburn administered the same approach to prepare me for the realities of work as a prosecutor and I am stronger and better for that.

But my tenure at Washburn has not come without challenges. My education coincided with a time when the school was without a dedicated point of contact for disability services – an absence which precluded proper planning and communication.

Washburn resolved the disability services void, and the time in between forced me to confront some of my own limited thinking as I navigate the road to becoming a blind prosecutor in the second half of life.

The important message here is that reasonable accommodation does not create an advantage for disabled students and it does not level the playing field. It does open the door to compete and participate for those who are willing to work twice as hard to defend their opportunities. While not a panacea, the ADA has done important work in the areas of accessibility for students and employees alike and is a step in a more enlightened direction.

At the same time, I caution that forced compliance for academic institutions can be a double-edged sword. It is human nature to resist compulsion and ADA requirements

turn the focus away from our basic instincts to accommodate individual differences and towards minimum compliance and legalistic delivery of services. Mutual understanding and initiative-taking communication are compromised by statutory obligations which create potential liability.

Personally, I would not have it any other way. Retinitis Pigmentosa and vision loss have shaped and molded my character. And without it, I would not be here today, seeking to serve as a prosecutor, defender, or judge for the remainder of my days. It is our own pain and suffering that instills compassion for others, and I am consumed by a need to help.

If I could change anything, it would be to help people understand how far the slightest bit of awareness and sensitivity can go in the life of a disabled person who often has much to offer as a friend, student, or employee. One needs only to scratch the surface to find another who knows who they are, is comfortable with themselves and may present surprising depth, fortitude and resiliency… which is a wonderful gift to share. u

Scott Geroux is a 3L at Washburn University School of Law and a nontraditional student who is pursuing a second career in the criminal justice system. After several decades spent raising his two daughters and working as a broker in the financial services industry, he felt called to serve as a prosecutor assigned to trafficking cases. Now in the final semester of academic work, before venturing out into various internships, he is focused on developing his trial, appellate and civil rights advocacy skills.

Geroux is originally from Wisconsin, where he grew up in a semi-rural factory town and attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Upon graduation, he moved to Southern California to see what life had to offer. After a decade, he relocated to Colorado with his new family and has spent the past 20 years in Superior, Colorado.

It has been eight years since Geroux felt called to be a prosecutor and took the LSAT. The law school experience has confirmed that calling. For Geroux, the ultimate end will be to serve as a federal prosecutor assigned to cases where organized human trafficking intersects with white-collar crime.

References

1. City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., 473 U.S. 432 (1985).

2. See, e.g., Scott LaBarre, NFB Passes the Test, Nat’l Fed. For the Blind (Dec. 1997), https://nfb.org//sites/default/files/images/ nfb/publications/bm/bm98/bm980102.htm (discussing a 1997 settlement over LSAC’s refusal to allow Braille writers and other accessibility issues).

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 19

Kansas Mock Trial: Pivoting with the Metaphorical Punches

By Kate Duncan Butler

Every trial lawyer knows that sometimes, you have to pivot. That’s the thrill of trial work; for every direct examination that goes exactly as you planned, there is a cross-examination that blows up so spectacularly that you throw out your notes and fly by the seat of your pants.

This year, Kansas Mock Trial practiced the art of the pivot.

If you’re not familiar with our mock trial program, the facts are simple: every year, the Young Lawyers Section of the Kansas Bar Association hosts high school students from all over the state in a mock-trial competition. Each team receives materials for a court case that includes witness statements, potential trial exhibits and the relevant law. The students split up roles, creating and mastering theories of the case from both the plaintiff’s and defendant’s perspectives. This competition season, our students tackled a challenging medical negligence and wrongful death case. They not only had to prepare opening and closing statements and witness examinations but learn about complicated legal concepts like comparative negligence and standard of care.

When we opened the 2022 competition season back in August, the mock trial committee had a single goal: to return to in-person competition for both the regional and state tournaments. Students had returned to in-person school, vaccination efforts had been ongoing for several months, and infection rates continued to drop after the late-summer spike. Even as we distributed the case problem in November, we felt strongly that we’d be able to have our Wichita and Kansas City regionals in person at the end of February.

The omicron variant, however, had different plans.

In early January, the national mock trial organization elected to move the national competition in May to a virtual format. And in late January, with the guidance of the Kansas Bar Association’s leadership, Kansas Mock Trial made the difficult decision to pivot to a virtual competition for regionals.

The teams had less than a month to prepare for Zoom competition, but they found their footing even on short

notice. Like last year, we used breakout rooms as a standin for individual courtrooms, with the students moving between the rooms as the rounds progressed. And despite a handful of technical hiccups, our 12 varsity teams and four novice teams performed admirably! In the end, six varsity teams, representing five schools, advanced to the statewide competition.

By the time we finished regionals, COVID-19 infection rates had plummeted. For that reason, we decided to make good on our season-long promise and hold the state competition in person! At the end of March, mock trial committee members, teachers, coaches, students and our dedicated legal professionals who’d signed up to judge the competition gathered at the Shawnee County Courthouse for the first time since March 2019. Finally, students returned to performing in actual courtrooms, standing at the counsel table to object, and moving about the courtroom like seasoned professionals.

The in-person competition was fierce. By the end of the tournament, only a handful of points separated some of the top-ranked teams. The crown, however, went to Hayden High School in Topeka, with the two Blue Valley Northwest High School varsity teams coming in second and third. Several students from these schools, as well as Olathe East, were also honored with some of the best individual performances of the tournament. Several judges remarked that the students outperformed some licensed attorneys they knew!

20 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association kansas mock trial

Every trial lawyer knows that sometimes, you have to pivot. This year, Kansas Mock Trial practiced the art of the pivot.

Like last year, the mock trial committee owes a great debt of gratitude to the incredible legal professionals who served as judges. Our judges came from all over the state and all walks of life; we had law students, sitting judges, trial attorneys, in-house counsel and even a few retired attorneys come out to help make our competition a rousing success. Also, special thanks to Lisa Leroux-Smith, Meredith Ashley and Nolan McWilliams for being part of our boots-on-theground logistics team during the in-person competition and Jakob Provo for his behind-the-scenes support and judge recruitment efforts. The tournament could not have happened without them.

We are already considering changes to the rules for next season, but no matter what happens, the future is bright for Kansas Mock Trial. After all, the program has now survived mid-season cancellation, a full season of virtual competition and a short-notice pivot. And we know that no matter the bumps in the road to 2023, the program has the support of many dedicated members of the KBA. As we said last year: it might not take a village to support Kansas Mock Trial, but it certainly takes a courtroom. u

Kate Duncan Butler is an associate at Barber Emerson, L.C. in Lawrence where her responsibilities include civil litigation, probate guardianships, juvenile offender defense and family law. She is also a former high school teacher and believes that mock trial is a great first step to inspiring students into the practice of law.

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 21

COHEN & DUNCAN ATTORNEYS, LLC STUDENT RIGHTS LAWYERS LEAWOOD AND WICHITA, KANSAS 913.956.1125 785.979.7361 studentrightslawyer.com • Education Lawyers for Students, Teachers and Professors • Higher Education Appeals for Undergraduate, Graduate and Professional School Appeals » Including Dismissal Appeals, Title IX Defense, Medical Resident Advocacy, Academic and Disciplinary Matters • Advocacy in Teacher and Administrator Conduct Cases • Advocacy for K-12 Disciplinary and Disability Cases cac@studentrightslawyers.com ad@studentrightslawyers.com vh@studentrightslawyers.com

Cli ord Cohen Andrew Duncan Victoria Henley

Update from the Office of the Disciplinary Administrator

By Gayle B. Larkin, Disciplinary Administrator

Last summer, after 35 years of service to the Kansas Judicial Branch, the public and the bar of the state of Kansas, Stanton A. Hazlett retired as the Disciplinary Administrator for the state of Kansas. Effective October 4, 2021, the Kansas Supreme Court conferred on me the privilege to fill the position vacated by Hazlett’s retirement.

Earlier this year, Chief Justice Marla J. Luckert offered me the opportunity to write an article in the column reserved for her in this journal. I gladly accepted and am excited to provide an update from the Office of the Disciplinary Administrator. In this update, I will briefly review Hazlett’s career, introduce my staff, highlight what’s new at the office and then maybe tell you a little bit about myself.

About Hazlett. For most of my legal career, the Office of the Disciplinary Administrator was not referred to by that name but rather simply as “Stan’s office.” That was because Hazlett created an environment of accessibility that extended the length and breadth of the state.

Hazlett provided hundreds of continuing legal education programs – from the four corners of Kansas to all communities in between. During his CLE presentations, Hazlett encouraged members of the bar to call the Office of the Disciplinary Administrator when they faced ethical dilemmas or when they had questions about the application of the Kansas Rules of Professional Conduct.

Under Hazlett’s leadership, the office created the Ethics Refreshers – a semi-monthly email message sent to the entire bar with a question designed to refresh and reinforce the bar’s familiarity with the Kansas Rules of Professional Conduct and the Rules Relating to the Discipline of Attorneys. (If you are not currently receiving the Ethics Refreshers and want to, please send an email message to attydisc@kscourts.org.)

Hazlett played an integral role in creating the Client Protection Fund Commission. Hazlett oversaw the investigation and presentation of claims that resulted in the return of more than $4,000,000 to clients victimized by dishonest attorneys. Hazlett was also involved in client

protection on a national level, serving as the Regional VicePresident of the National Client Protection Organization.

Hazlett also served on the Kansas Lawyer Well-Being Task Force, searching for ways to improve the well-being of attorneys throughout the state.

Finally, Hazlett prosecuted attorney disciplinary cases in a way that served to protect the public, while affording the respondent attorneys dignity and respect.

Hazlett was a dedicated public servant who served the legal profession well. His legacy with respect to the Client Protection Commission and the Lawyer Well-Being Task Force as well as his dedication to ensuring a fair process will serve as a monument that will benefit Kansans and the bar for many years to come. Thank you, Stan.

An Amazing Staff. Hazlett, with some assistance from me, worked hard to assemble a hard-working and professional staff. We hired skilled litigators who possess a balanced sense of fairness and exhibit professionalism. We also hired experienced and professional investigators, as well as patient, detail-oriented and hard-working administrative personnel. Though this paragraph hardly does them justice, I am proud to introduce each member of the staff:

• Matt Vogelsberg, Chief Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Deb Hughes, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Gary West, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Kathleen Selzler Lippert, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Alice Walker, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Julia Hart, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

• Amanda Voth, Deputy Disciplinary Administrator

The investigative staff includes:

• Tom Stratton, Director of Investigations

• Crystalyn Ellis, Assistant Disciplinary Administrator

• Katie McAfee, Assistant Disciplinary Administrator

22 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association

from the disciplinary administrator

• Royetta Rodewald, Special Investigator

• Dave Brede, Special Investigator

• Tim Schilling, Special Investigator

Finally, and most importantly, our office runs smoothly only because of the professional administrative staff that we have:

• Kayla Layne, Administrative Legal Secretary

• Mitzi Dodds, Administrative Legal Secretary

• Laine Beal, Administrative Legal Secretary

What’s Next? To say that I have big shoes to fill is perhaps the understatement of the year. However, I do have plans for the office. I have ideas on how we can take what Hazlett started and enhance the outreach efforts of the office, make the office even more accessible and improve the disciplinary process – with the dual goals of reducing attorney misconduct and protecting the public.

Expansion of Investigative Staff. Last fall, shortly after beginning my new position, I sought and obtained permission from the Supreme Court to expand the investigative staff. Previously, the investigative staff included three staff members. The Court approved my request to expand the in-house investigative staff to also include three full-time attorney investigators. My goal in expanding the in-house investigative staff is to reduce the time it takes to investigate complaints lodged against attorneys. Reducing the time it takes to investigate a complaint will benefit the complainant, the respondent and the public. I am hopeful that reducing the time it takes to investigate complaints will lead to earlier interventions, with the ultimate goal of preventing additional misconduct.

While we will continue to rely on volunteer attorney investigators through the ethics and grievance committees from across the state, we will investigate more cases in-house. Moreover, the in-house investigators will be available to assist the volunteer investigators in timely and professionally investigating complaints against attorneys.

Translation of Complaint Form and Claim Form. To make the attorney complaint process and the client protection claim process more accessible, earlier this year we had the complaint form and the client protection claim form translated into the Spanish language. Both the English language and Spanish language complaint and claim forms are available on the Internet.

Additional Rule 235 Efforts. Regularly, our office receives calls from members of the public seeking to find documents that were held by attorneys who have either died or left the practice. Unfortunately, most of the time we do not have any information to provide the caller. However, we have recently

An Amazing Staff. Hazlett, with some assistance from me, worked hard to assemble a hard-working and professional staff.

made efforts to improve that situation. Under Rule 235, the chief judge of a judicial district may appoint an attorney to protect the interests of an attorney’s clients when an attorney is transferred to disabled status, disappeared, or died, or when the Supreme Court has suspended or disbarred the attorney. For the convenience of the chief judges, we drafted a sample order which could be entered under Rule 235 and we distributed that order to the chief judge of each judicial district and the clerk of each district court. We have also requested a copy of all orders previously issued under Rule 235 and its predecessor, Rule 220, from all judicial districts. Also, we have requested to be provided a copy of each Rule 235 order as it is entered. Finally, we have developed an internal database that identifies the name of the attorney appointed to protect clients’ interests under Rule 235 and its predecessor, Rule 220. We are hopeful that going forward we will be able to provide helpful information to members of the public when they call seeking assistance in this regard.

Diversion Program. I am hopeful that the expansion of the in-house investigative staff will help us to earlier identify respondents who could benefit from a corrective plan available in the attorney diversion program. Utilizing the law office management resources available through KALAP, we hope to find ways to prevent misconduct from recurring.

Website. To enhance transparency, we also have plans to expand the information available regarding attorney disciplinary cases on the Internet. We plan to add a calendar to our webpage which will show the dates of attorney disciplinary hearings and oral arguments. In addition to the Supreme Court opinions on attorney disciplinary cases which are already available online, we plan to make additional documents, including formal complaints, answers and final hearing reports available on our webpage.

Future of Attorney Regulation. For the past two years, I have served on the National Organization of Bar Counsel’s Committee on the Future of Attorney Regulation. The committee consists of attorney regulators from all over the country. The committee was charged with examining issues

www.ksbar.org | May/June 2022 23

u

from the disciplinary administrator

that face attorney regulators throughout the country and identifying new ways to approach the regulation of the everchanging landscape of the practice of law. Ultimately, the committee will be publishing a white paper that will contain recommendations for implementation in attorney regulation offices nationwide. Once the paper is published, I look forward to seeking to implement the recommendations in Kansas.

Have an Ethical Question? If you find yourself facing an ethical dilemma or if you need information about the application of the Kansas Rules of Professional Conduct, as always, please feel free to reach out to our office. We are happy to discuss the situation and identify the rules which you will need to consider in resolving your issue. We can be reached at attydisc@kscourts.org and 785.435.8200.

Thank you to Chief Justice Luckert for providing me with the opportunity to introduce myself and provide you with an update from the disciplinary administrator’s office. I look forward to serving the Kansas Judicial Branch, the public and the bar in my new role as Disciplinary Administrator. u

Gayle B. Larkin graduated from the University of Kansas, School of Law in 1990. She started her career as a criminal prosecutor – first as an Assistant District Attorney for Douglas County, Kansas, and later as an Assistant Attorney General. While in the Attorney General’s office, Ms. Larkin was cross-designated as a Special Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Kansas. In 1999, she began her career in attorney discipline. From June 1999, through September 2021, she served as Counsel to the Kansas Board for Discipline of Attorneys. She advised the board and drafted final hearing reports following disciplinary hearings. From January 2003, through June 2021, she also served as the Admissions Attorney, investigating and prosecuting bar admissions cases related to character and fitness. In October 2021, the Kansas Supreme Court appointed Ms. Larkin as the disciplinary administrator. As the disciplinary administrator, she supervises the investigation and prosecution of attorney disciplinary cases, bar admissions cases, and client protection fund claims. In addition, she oversees outreach programs sponsored by the office designed to educate the bar on the Kansas Rules of Professional Conduct and prevent cases of attorney misconduct.

24 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association t

What the News Media Wants

By Kim Wilhelm

Note from KBA: For this edition of the column from your KBA Media/Bar Committee, we asked Kim Wilhelm, news director of KWCH-TV/KSCW-TV in Wichita, to provide some thoughts on day-to-day news coverage of courts, with the continued goal of helping to build understanding between news journalists and the KBA Journal’s readership.

For those not familiar with the term, a “news director” is the person responsible for overseeing and orchestrating daily news coverage at a broadcast station, including supervising crews of reporters and video journalists and making decisions about how to allocate precious minutes of broadcast time. No, the daily news does not write itself. It is not imposed or dictated unilaterally by some mysterious source from on high. Each newscast, newspaper, or other news publication is the result of numerous difficult decisions made by dedicated people like Wilhelm, who exercise their best judgment about what information to convey to their audience or readership. They put their reputation on the line every day and publicly stand by their work. It is a challenging and often thankless job, but one that is vital to our society.

the giant VCR-like equipment broadcasters used back then. Journalists now may ask to live tweet or live stream the court proceeding. But the desire to cover the most impactful stories in our community has not changed.

So, what do members of the news media want? Why are they interested in some cases and not others? How come they only show up for part of a case? Why do they call for comment –don’t they know we can’t talk about it?

Here are Wilhelm’s thoughts on “What the News Media Wants”:

The courtroom is absolutely silent. I slowly bend down to push the stop button on my recording deck because my videotape has run out. I am holding my breath because I am so nervous. I slowly and softly push the eject button. The spring-loaded cassette tray jumps open with such mechanical force that I actually gasp. Everyone in the courtroom turns towards me no doubt thinking “who the [bleep] is so loud?” and that’s when I realize my sudden gasp has turned into a court-stopping case of hiccups.

And that was my first experience covering a court case as a journalist.

Fast forward many years and some things have changed. Today’s equipment is much smaller and quieter than

Most news organizations will cover high-profile incidents and/or unique cases. Most will not be there gavel to gavel because of resources. For the most part, gone are the days of big trial coverage and Court TV-like setups. Instead, local media may aim to cover the most compelling portion of a case.

The pandemic has opened an interesting opportunity. We all have become more comfortable with the tiny camera on our computers or phone for virtual meetings. Institutions that have traditionally said “no thanks” to full camera access have equipped themselves with the ability to broadcast meetings out of pandemic necessity. Now imagine being able to regularly broadcast court cases with the ease of a few buttons. In a day when transparency and trust is the goal, technology is allowing all of us to open up and reach more people. What an opportunity to take the public into the courtroom to see

26 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association

from the KBA media-bar committee

the hard work done by judges and attorneys – to truly see justice in action.

Professional journalists are guided by ethics. The Society of Professional Journalists’ list of principles includes:

• seeking the truth and fully reporting it,

• minimizing harm,

• acting independently, and

• being accountable.

Newsrooms have lengthy discussions about stories and the impact we leave. We understand we may be encountering people on the worst day of their life after a tragedy. We consider the harm that may be done by publishing a graphic police affidavit online. We try to make responsible decisions while providing information to the public. Do we always get it right? No. But we try to learn from each misstep and educate our teams.

Reporters, just like attorneys, come in all experience levels. Most newsrooms do not have a dedicated court reporter but general assignment journalists who may be on a political story one day and a farm story the next. Educating our journalists about courts is important. Most new reporters have never been in a courtroom until they are assigned to cover a story. And that’s pretty intimidating.

So how do we both improve what we do? I’m proud of the work the KBA Media Bar Committee is doing to help educate journalists and KBA members. Building relationships is truly the best way to create trust and have honest conversations.

Thank you to all who have provided information to a journalist, granted an interview, or taken the extra time to make sure a reporter understood what just happened during a hearing. We all benefit when journalists are comfortable and capable in our courts. Thanks to the kind judge many years ago who saw an embarrassed young reporter with ridiculous hiccups in his courtroom and got her a drink of water. u

27

Kim Wilhelm is the news director of KWCH-TV/KSCW-TV in Wichita, Kansas. She serves on the KBA MediaBar Committee.

NEARLY HERE! The compliance deadline is Don’t worry. The KBA has you covered. CLE S u pportingYour Success www.ksbar.org/cle

ON-DEMAND

Continuing Legal Education

From the Kansas Bar Association

Complete your compliance hours from the comfort of your home or office!

All courses are available individually, but if you need more than a few, check out our On-Demand

All Access Pass, which gives you access to all of our on-demand courses for only $499.

Choose from hundreds of hours of CLE programming, including:

Kansas’ New Notary Laws

1 hour credit in KS

2021 Plaza Lights Institute

7.5 hours credit in KS

(Includes 1 hour ethics credit)

Medicaid Planning Panel

1.5 hours credit in KS

Corporate Transparency Act of 2021

1 hour credit in KS

Corporation Laws Sneak Peek: Recent Changes to the DGCL

1 hour credit in Kansas

LGBTQ + Issues in the Law

2 hours credit in Kansas

(Includes 1 hour ethics credit)

AND MANY MORE!

Check our website for the latest live webinar and in-person options!

KSBar.org/cle

50 years of Title IX: So Much More Than Sports

By Ashley Rohleder-Webb

I: Introduction

During this 50th anniversary year of the passage of Title IX, there are seemingly endless articles, television specials, and similar tributes being produced. Opinion articles during the NCAA Basketball Tournaments compared to treatment of male and female college athletes and just how much “madness” the NCAA dedicated to the respective tournaments.1 During warmups for their Final Four game, the University of Kansas men’s basketball team wore shirts with an excerpted line from Title IX on the back, part of Adidas’s “Impossible is Nothing” campaign.2 ESPN specials are scheduled for this summer.3 During Super Bowl LVI in February 2022, a special introduction video honoring female athletes aired, leading into the honorary coin toss by Billie Jean King, accompanied by players from girls’ football teams around California.4