Ludwig Wittgenstein noted in his treatise On Certainty that “there are an enormous number of general empirical propositions that count as certain for us. One such is that if someone’s arm is cut off, it will not grow again.” The philosopher believed this as a “truism” and one drawn from witnessing his older brother, the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, suffer through a debilitating injury. Less than one month after the start of World War I, Paul Wittgenstein was shot while assigned as junior officer in the Austro-Hungarian army while serving on the Austrian eastern front in Galicia on a reconnaissance mission. His right elbow shattered by a bullet, the concert pianist’s arm was amputated in a Russian field hospital in Ukraine, after which he was deported to an invalid ward within a Siberian prison camp in Omsk. While interned there, Wittgenstein strove to retrain and strengthen his left hand. With a piece of charcoal, he drew the outline of a piano keyboard on a wooden crate and practiced obsessively by tapping out the most complex Chopin pieces seven hours a day. Regarding this arduous rehabilitation, he later notes, “it was like climbing a mountain. If you can’t get up one way, you try another.” Eventually repatriated by means of a prisoner exchange program, Wittgenstein persevered with his efforts to perform as a concert pianist combining pedalling and hand movement techniques previously regarded as impossible for a five fingered pianist. Though his hand would not fully recover from his injury, his aptitude as a pianist allowed him to replicate the effects of ambidexterity with just the right hand. In 1915, he debuted an “able bodied” Concert Piece in the form of Variations for the Pianoforte Left Hand in Vienna, with a performance that resounded in dissolving the gap between apparent ability and disability to give the impression, according to critics, that four hands were covering the keyboard. Supported by the Wittgenstein family fortune, he continued to commission leading composers of the time –Richard Strauss, Sergei Prokofiev, and Benjamin Britten – to write new works for piano that required the use of the left hand alone. It was Maurice Ravel who composed Piano Concerto for the Left Hand as the most virtuosic among these, and it remains something of a rite of passage for two-handed players.

Wittgenstein’s single-handed address of “twohandedness” negotiated the complex demands of a musical score to surpass corporeal finitude and to

envision how a work of art may be expressed beyond the limits of its formal construction and internal logic of organization. Piano Concerto for the Left Hand serves to inspire Composition for the Left Hand as the title for an exhibition that plays and unfolds as a dialogue, an entanglement, perhaps even mutual mumbles, between two collections–one historical in content and built by the collector Rasmus Meyer (a Norwegian industrialist and committed “garden architect”) in conversation with a contemporary art collection built by Erling Kagge, a Polar explorer and writer on the subjects of silence, walking, and the durational. Each collection is situated on either end of a century and across a timeline whereby art has emerged in accordance with dramatic spatial and temporal paradigm shifts.

As a series of sequences and accents, the exhibition is composed as a working draft reflecting on what the writer Ursula LeGuin prefaces in her Left Hand of Darkness, as an “experiment wherein thought and intuition can move freely within the bounds set only by the terms of the experiment.” It is also a project that respects the contradiction inherent in the author/ artist who sets out on a committed trajectory within the stranglehold of techne: “I talk about the gods; I am an atheist. But I am an artist too, and therefore a liar. Distrust everything I say. I am telling the truth. The only truth I can understand or express is, logically defined, a lie. Psychologically defined, a symbol. Aesthetically defined, a metaphor.”

Although the exhibition privileges the left-handed in its association with intuition, eternity and mysticism, and as epitomized by art, it does so by leaning the left over its counterpart, as the right-handed is aligned with the linear flow of history, as epitomized by science. This is not intended as a dialectical exercise of oppositions–between the awkward on one side, and the logical, taut, and moral on the other. Instead, the project follows the way the brain is wired to respect how its left and its right sides work symbiotically to address complimentary modes of consciousness. In this way, left-handedness stands as a way, as Jerome Bruner notes in On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand–to imagine how “the left hand may tempt the right hand to draw freshly again when the task is to find a means of imparting new life to a hand that has become all too stiff with technique.”

Composition for the Left Hand is an exhibition that takes the form of a manuscript that evolves by interweaving the historical works of art from the collections of Rasmus Meyer and Kode together with works from the contemporary collection of the polar explorer Erling Kagge. Unpacking My Library , the 1931 essay by Walter Benjamin serves as a valid reference in addressing the deep dive required to explore each of these vast collections, and to find the threads and constellations for a series of shared conversations and debates in their being reassembled for the sake of an exhibition. Benjamin speaks to the voracity with which one begins to unpack and the difficulty with which one may stop this activity. Taking Benjamin’s lead in that any collection is as relevant as its parts and the relevance of those works as they stand through time and history, the motivation of this exhibition was to draw selected works from their inert repository and to bring historical works of art in correspondence with the contemporary works from the Kagge Collection to illuminate their role in helping us to understand the relevance of the wider realm of their production. As Benjamin reminds us in his essay –collecting involves desire and that that although “every passion borders on the chaotic, the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.” More than that, Benjamin, adds that the chance and fate that suffuse the past before his eyes are conspicuously present in the accustomed confusion of these the works. He asks – “for what else is this collection but a disorder to which habit has accommodated itself to such an extent that it can appear as order?”

In reconciling two very different trajectories - one in researching historical works in storage and how they might regain meaning or rather, convey meaning in being in proximity to other works, with whom they had never intended to be in dialogue with. In this sense, the exhibition is built out with the intention to be necessarily a cacophonic and dissonant composition. In understanding packing and unpacking as two separate processes, Benjamin emphasizes that each serve as two sides of the same impulse, marked by chaos at each pole, whereby meaning is gained from dismantlement, in the dissolution of set narratives, and in the reassembling and putting back together that may offer new encounters of interpretation and a revision of perspective. Benjamin denotes this very process as that which defines the “existence of a collector, as someone dialectically pulled between the poles of disorder and order.”

The presentation of historical works adjacent to those from the recent decades attempts to put side to side an address of the world according to the time in which the respective artists lived and live, how they pictured/ picture their environment and the cultural and political changes of their time, and how these artists attempted to intervene within the constraints of their institutional frameworks and immediate surroundings by combining depiction and narrative with the vernacular, while embracing the role of the artist as a modern, selfreflective subject.

The active pulling of works out of storage, the reviewing, the reshuffling, the conservation required for its reanimation, the lifting of objects from repose together with the embodied memories to be recast and reencountered anew, involves a complex process that is messy, untidy, unruly, provocative, exploratory, for the purpose of setting up new correlations, perhaps postulates, via revised adjacencies. Hence, Composition for the Left Hand offers the challenge proposed by Benjamin nearly a century ago anew - to “join (me) in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open…to join (me) among the piles of volumes that are seeing the daylight again….to provide insight into collecting rather than on a collection.”

Rasmus Meyer Ground FloorLawrence Weiner

A curatorial note of memory. When I arrived as in Norway in 2005 to curate an exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo entitled Draft Deceit, Lawrence Weiner and his critical compatriot partner, Alice Weiner came to Oslo to spend some time at Ekely during what had been a very snowy winter. Throughout the installation, there was ample time for conversations and banter. I spoke to my questioning in how to enter my position as Director of OCA, in deciding what project to start with – as not a one-off exhibition but a multiyear project that might be relevant for Norwegians, within Norway, across Scandinavia, but which also linked to the country and the region to the world. As someone who has always opened the exhibition process to social and political coordinates, I became perplexed by Scandinavia’s legacy as a hotbed of liberation and free love throughout the 1970s, because it certainly didn’t seem to be that way at the time I lived there. Lawrence Weiner suggested that I watch Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious Yellow. Although a film by a Swedish director and, according to Sjöman, a film about Sweden throughout the 1960s, it opened an entire field of research that led me explore Norway’s complex history with regard to feminism, labor movements, and leftist politics. It led me to understanding it as a haven for experimental radicals such as Wilhelm Reich at a time when he was most prolific, and it led me to curating Whatever Happenned to Sex in Scandinavia? Lawrence Weiner commences the exhibition with a work in the institution’s bathroom – this as Erling Kagge, who has provided the works throughout this exhibition, choses to exhibit the vast collection of Lawrence Weiner in the entry bathroom within the Arne Kosmo villa, where he lives in Oslo. Erling reminded me of an instance when, years ago, he was visited by Weiner, who used the lavatory and upon returning stated bluntly (as he usually would), “finally, some art I can jerk off to.”

A pioneer in the Conceptual art movement, Weiner viewed language as his primary medium as a way to redefine the status of the artist and challenge, still in the 1960s, what constituted a work of art. By using language as his material, Weiner classified his work as sculpture that shared ground with philosophy, linguistics, anti-capitalist politics and poetry. Each work referred to Weiner’s generic description of their content – LANGUAGE + THE MATERIALS REFERRED TO – and his position that language itself

USE ENOUGH TO MAKE IT SMOOTH ENOUGH ASSUMING A FUNCTION

, 1999

Language + the materials referred to Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021)

Erling Kagge Collection

is three-dimensional, that the work is what it says it is. His work sought to transcend the restraints of any particular culture and context, leaving it open to the individual’s intellectual as a ‘receiver’, to read the work. In doing so, Weiner understood his work ever present, ever in flux and never ever finished. His mode of address offered a radical redefinition of the relationship between the work of art and the receiver, emphasizing this collaborative engagement that was completed by the viewer’s assimilation of their own experience.

The Rasmus Meyer Collection frames work from a kaleidoscopic historical period of social change, the late 19th to early 20th centuries – a period accompanied by spatial and temporal paradigmatic shifts that contributed to the dizzying experience of modernity – with its intellectual controversies, the introduction of psychoanalysis, its social revolutions, the formation of states, the fervor of early feminism and early labor movements, and the critical study of political economy, which would render explicit those contradictions inherent within the capitalist mode of production. The fin-de-siecle introduced modernity as, according to Charles Baudelaire wrote, “the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art, of which the other half is the eternal and the immutable.” In revisiting the collection, Nature is deemed historical –not only because it evolves and constantly changes, but because it has been profoundly, often negatively, affected by human history. Natural history reveals a dynamic and often catastrophic interaction between the planet and human history. Correlating contemporary works collected by a polar explorer and writer on subjects such as walking and silence with the historical works with works collected by an industrialist, albeit avid garden architect casts a conversation about how art is a synthesis of the political, social and economic rooted in nature (as art) and part of an enlarged field called the environment. 1

Iceberg , 2004

Mark Handforth (1969–)

Aluminum, reflective vinyl and paint

Erling Kagge Collection

Mark Handforth

According to the pack of philosophers – Plato, Aristotle, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, and extending to teachings of Indian, Chinese, and Japanese aesthetics –beauty was conceived as something harmonious, an organic whole and an object of pleasure. Edmund Burke worked out the concept more fully in the 18th century – suggesting that mathematical proportion, usefulness, and perfection were not the attributes of beauty and the philosophers thereafter agreed that whatever pleasure arising out of the contemplation of beauty was a different experience that arising out of erotic or sexual pleasure and interest. Immanuel Kant proposed “uninterested pleasure” in that the judgement of something as beautiful does not arrive on whether it is agreeable or pleasurable or liked. And it was Theodor Adorno who swept the category under the rug altogether and evolved the category of the ugly to resist art’s ascension into the culture industry and into commercialization. He wrote: “the impression of ugliness stems from the principle of violence and destruction. The aims posited are unreconciled with what nature, however mediated it may be, wants to say on its own. In technique, violence toward nature is not reflected in artistic portrayal, but it is immediately apparent.” The term Adorno negotiated, “cultural landscape,” would be a model whereby ugliness “would vanish if the relation of the individual to nature renounced its repressive character, which perpectuates rather than being perpetuated by – the repression of the [individual].”

That particular objects and practices are not recognized by exhibiting institutions beyond their thingness and what constitutes them as such as art, is in itself, a symptom of a system gone amok, or not gone-amok enough. It is important to take into consideration Fred Moten’s writings around the “Magic of Objects” as a way to provide insight into a series of practices articulated through race, class, gender, and sexuality as to recognize the “social capacity to render life as history – necessary for any cultural product.” In this respect, Moten calls for an imagination of a context for analysis whereby race, class, gender and sexuality as four articulating structures that would be granted historicity, politics and practice in relation to one another, and as mutually recognizable. 2

Rasmus Meyer Gift Shop and Room 112

Diamond Stingily

3

Wish You Were Here , 2008

Ceal Floyer (1968–) postcard holder

Edition 2 of 3 + 2 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Diamond Stingily attests to having a deep encounter with Collette Thomas and The Testament of a dead Daughter, a book that has served as a profound influence for her as a writer, performer, and visual artist. Collette Thomas, one of Antonin Artaud’s “daughters of the heart,” flashed briefly before an unsuspecting Parisian literary world in 1946 to deliver a reading from Artaud’s Fragmentations. Her book was published in 1954, under the pseudonym Rene, and was comprised letters to Artaud, accounts of her early incarceration and suffering, along with tales wrenched from her tortured being. Her mental condition steadily worsened and she was to spend the rest of her life in private clinics. As an artist who weaves together personal and social memory composed of everyday objects, Collette Thomas’ diary and an anthology of poems, Stingily’s Caption is a testimony about the cruelty of love in which the past and future are entwined, as it is a novel of death and resurrection. Stingily creates work that draws from the significance of the elephant as a mammal that communicates by touch, sight, smell and sound, and exhibits mirror self-recognition, self-awareness and cognition as demonstrated in dolphins. Excelling in long term memory with one of the largest brains in the animal kingdom, elephants’ brains hold as many cortical neurons as human’s. Matriarchy is the hub of the complex social network of elephants. The matriarch who is the eldest of the group serves as the leader of the group until death, after which her eldest daughter takes over. The elephant is also known to show concern for the dying and the dead, which supports Stingily’s interest to address death as a way to, according to the artist, “encourage to conquer your fears, so that you might as well get over that shit shat.”

Elephant Memory, a chainlink from the artist’s memories of the chainlink fences of her home town of Chicago, serves as the armature for long braids of synthetic Kanekalon hair (a signature element of her installations) – sourced from childhood memories and her mother’s doing hair for a living. Drawing from an interest to produce work that carries distinct class markers and a firm sense of place, attuned to the texture of personal memory (and the politics that underlie it). 4

Elephant Memory #2 , 2019

Diamond Stingily (1990–)

Synthetic hair, galvanised steel chain, galvanised steel hook

Erling Kagge Collection

The Eruption of the Volcano Vesuvius, 1821, is a canonical work by Johan Christian Dahl painted after his visit to Naples in 1820 having had witnessed the eruption of the volcano at Mount Vesuvius. Having painted several moonscapes before, he was compelled to continue to sketch the active volcano, ascending the mountain several times to observe the natural phenomena. His work would exemplify the Kantian category of the sublime, that within nature which elicits in the human mind alternating responses of repulsion and attraction. Dahl’s painting introduces into the exhibition a concept that the Canadian poet Anne Carson refers to as “volcano time” – as a way to address temporal plurality, to set the present condition against something ancient, something colossal and in relation to a unpredictable futurity. That is to say that being in the presence of a volcano contributes to the formation of an experience whereby the phenomena is perceived psychologically and physiologically, as lava hurdles forth with terminal velocity to dramatize the duality of the sensible experience and mental perception, modifying the former by infusing the latter with anticipation. The pastoral backdrop may remain untouched although not inevitably depending on winds gusts and internal earthly forces wherein violent and active phenomena may eventually, according to geological time evolve into an arctic glacier.

The 19th century paintings through the ground floor depict the nature as landscapes to convey the phenomenal power of waves, the fury of the storms at sea, ethereality of the clouds, the magnitude of the forests as a way to convey the experience of nature. Norwegian painters Johan Christian Dahl left Norway in order to study in Dresden – as did his pupils, Thomas Fearnley, Knud Baade, and Peder Balke – only to return to continue to depict landscapes unlike those painted by his colleague, Caspar David Friedrich. The Rasmus Meyer collection emphasizes the position of Norwegian painters in this genre also represented by works by Hans Gude, who had been based in the Dusseldorf Art Academy as an instructor of landscape painting, who commanded authority there as a teacher as did Adolph Tidemand School of Painting. Although Tidemand deferred to the genre of motifs, Gude and Dahl addressed naturalism as anchored within the realm of observable natural phenomena. Dahl attempted to transmit a naturalism of his day as real although his impression in rendering was rather a simulation of a particular realm in order to generate an atmosphere, through contemplation of nature that incorporated all the senses.

View from a Window at Quisisana , 1820

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Copy of an Italian Landscape by Jan Both , 1813

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Time , 2004

Hills near Quisisana in morning Light , 1820

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Boats on the Beach near Naple s, 1821

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Scene from Ischia , 1820

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

An Eruption of Vesuvius , 1821

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

The Casa del Portinaio in the Villa Borghese , 1821

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Moon , 2003

Roe Ethridge (1969–)

C-print

Edition 2 of 5 + 2 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Karen Kilimnik (1955–) Water soluble oil on canvas Erling Kagge CollectionKaren Kilimnik

Karen Kilimnik (1955) is an artist who produces oil that allude to the Romantic tradition and to historical allegories, although inscribed by irony and the vaguely sinister. A strident environmentalist, Kilimnik has pro duced works that connote historical landscape paintings as a reflection of her concern with the natural world, although the oceans, skies, mountains, and icebergs, are rendered in such a way as if to be captured in decisive moments, at the juncture of imminent change or danger.

The Moon

Poetically the symbol of the Moon figures into many of the works. Traditionally associated with the feminine principle, with water, particularly with the sea, and with change and growth, while its phases, natural symbols of mutability and impermanence. The early 20th century mystic Madame Blavatsky had taught that the powers associated with the moon were responsible for the division of the sexes, for generation and for emotion, while the solar powers were in conflict with them and responsible for spirit and intellect. Later W.B. Yeats wrote A Vision as a meditation on the relationships between imagination, history and the occult. In this poem published in 1925, Yeats asserts a classification in outlining the 28 phases of the moon which represent states of the human personality. Each phase is pictured as of the spokes of a Great Wheel, which is “every completed movement of thought or life,” using geometric images to construct an esoteric system. 11

Roe Ethridge

Ethridge (1969) works with picture as document –his photographs recording just what the camera sees. Inspired by the work of Richard Prince and Paul Outerbridge, Ethridge adopts the armature of commercial photography to dissolve the distinction between no discrimination, and editorial and art, between document and construct. Etheridge seizes photography’s double life in moving fluidly between art and advertising, embracing evolving forms of technology within commercial media. In pursuing this slippage, Ethridge proposes pastoral landscapes without the intention to reference the Romantic tradition of landscape. Instead, these images steer ahead by alluding to the polemics of contemporary land ownership and to the capitalist logic inscribed by the perpetual production cycles which sustain purposeful obsolescence. Although the artist focuses on objects as close-ups, Ethridge is moreover interested the

Moon , 2003–2008

Roe Ethridge (1969–)

Archival Inkjet Print Edition 2 of 5

Erling Kagge Collection

J.C. Dahl , 1821

Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844)

Marble

Kode

underlying networks and circuits of hyper-managed systems of production and distribution that are clearest seen from a distance. In contrast to the earlier traditions in photography, Ethridge acknowledges the impossibility of photographic originality, leaning into the popular culture of photography in employing as tropes astro photography, motion photography, editorial and fashion photography, portraiture and landscape. He notes: “Images are redundant. I am implicating myself as part of that redundancy.”

The curator Kate Bush wrote about his series entitled the Moon , to explain that Ethridge sourced images of the moon from the roof of his home in Brooklyn, using an 8 inch Meade LX90 telescope to make original photographs of an unoriginal subject. Ethridge’s “moon” is digitally repeated, twice or more, within the frame of a single photograph – rather like the sequential chronophotographs of Muybridge or Marey – in order to suggest the trajectory of the moon’s movement across the sky. “The moon moved through the frame in a perfectly straight line.” 13–14

Cultural Landscape as a Domain

By the 19th century, the landscape of modernity was populated by steam engines, factories, railroads, and cities transformed rapidly by industrialization. The widened distribution of print media – daily newspapers, telegraphs – and eventually telephones sustained larger networks of communication within mass social movements. Composition for the Left Hand seeks a dialogue with the collection’s works from the 19th century to underscore how the nature of that time has been eroded by pollution, toxins, and by the century long effects of climate change exacerbated by human negligence, avarice and militarization. As Walter Benjamin wrote in the aftermath of first world war, “human multitudes, gases, electrical forces were hurled in the open country, high frequency currents coursed through landscape, new constellations rose in the sky, aerial space and ocean depths thundered with propellers, and everywhere sacrificial shafts dug into Mother Earth. This immense wooing of the cosmos was enacted for the first time on a planetary scale” – that is, in the spirit of technology. Yet, technology, harnessed to the capitalist imperialist purpose of mastering nature, “betrayed man and turned the bridal bed into a bloodbath.” By the early 20th century, nature entered into an enlarged domain, a hybrid of the environment and the political – a field manipulated by private interests of profit and consequently of political affiliation and political ideology.

As technology intervened to mediate nature in response to the interests of capitalist development, the 19th century experience of nature as simultaneously threatening and majestic, as envisioned by Kantian aesthetics, was enlarged into the domain referred to by Theodor Adorno as “cultural landscape”, as “an artifactitious domain that must at first seem totally opposed to natural beauty to challenge if not denounce environment merely as a depiction.”

Torbjørn Rødland

The 19th century brought forth an interest in animal studies with the introduction of Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species in 1859. This instantiated an indissoluble link to the natural world that would later be accompanied by a humanitarian address of animals and animal reform. As scientific inquiry advanced, animals became incorporated as objects to be investigated to learn more about the human body, its actions, illnesses, and pathologies. Animal behaviour lent more to the understanding about human behaviour and eventually, to an exploitative animal experimentation, genetic engineering, dog breeding and training, beyond the traditional hunting of animals for food and hunting. 32

The Elbe in Moonlight , 1841

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Breakers with the Top of a Mast and Tackle , undated

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Dresden by Moonlight , 1843

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Fjord at Sunset , 1850

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas mounted on wooden board

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Shipwreck on the Coast between Larvik and Fredriksvern , 1846

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

View of a Birch Tree in Hallingdal , 1845

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode

Shipwreck on the Coast of Norway , 1830

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas Kode

No Title (We grow them) , 2005

Raymond Pettibon (1957–) pencil and ink on paper Erling Kagge Collection

Mountains on Hardangervidda at Sunset , 1840

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Rasmus Meyer Room 109

View from Stalheim over Nærøydalen , 1836

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

River between steep Rocks , 1825

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Birch Tree in a Storm , 1849

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas Kode

Rabenauer Grund , 1836

Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

The Beast and the Sovereign was written by Jacques Derrida as two volumes, a natural history which considers the living being with the treatment of the so-called animal life in all ot its registers – his own motivation to organize into logic the submission of the beast and the living being to political sovereignty. Derrida explores the contradictory appearance of animals in political discourse, where at times, the political subject and the sovereign state appear in the form of the animal, and at other times, superior to animals. According to Derrida, “Just where the animal realm is so often opposed to the human realm as the realm of the non-political to the realm of the political, and just where it has seemed possible to define man as a political animal or living being, a living being that is, on top of that, a political being, there too the essence of the political, in particular the state and sovereignty, has often been represented in the formless form of

Forest Stream , 1825

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Collection

Untitled (Illness) , 2005

Torbjørn Rødland (1970–)

C-print on Fuji Crystal Archive paper mounted on aluminium Edition 2 / 3 + 1AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Pork said the Bear , 1900–10

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Oil on cardboard Kode

The lower Falls at Trollhättan , 1826

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

River between steep Rocks , 1825

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Puppy , 2010

Lutz Bacher (1943–2019)

Painted plaster and metal, circular glass top

Erling Kagge Collection

Rocky Coast near Bergen , 1834

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Coastal Landscape at Sunset, 1819

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Study of two Calves , 1830

Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

animal monstrosity, in the figure without a figure of a mythological, fabulous and non-natural monstrosity, an artificial monstrosity of the animal.”

Derrida notes several specific animals as their anthropomorphic figure within fables. The wolf, he notes, be it in fantasy, narrative, fable or in rhetorical treatment, serves as the animal that is most referred to in relations to questions of animal and the political, of the politics of animal, of human and beast in the context of the polis and the social body. But Derrida also emphasizes that it is the she-wolf that is the symbol of sexuality and sexual debauchery. The monkey - inpenetrable in terms of communication,the dolphin – intelligent as humans, and the elephant – as the phenomenal beast who is both the subject and the object of the gaze of the Sun King, a ≈ king of light and source of light. 32, 145

Theodor Kittelsen

Theodor Kittelsen’s formal education as an artist was hindered by economic hardships although the patronage from a wealthy townsperson allowed him to attend Wilhelm von Hanno’s drawing school and the Royal College of Art and Design in Oslo. He proceeded to continue his studies in Munich together with Erik Werenskiold, Christian Skredsvig and Eilif Peterssen although his professional success as an artist was hindered by his departure from the standards for Realism in the day. As he struggled to support himself as an artist, he was eventually hired to illustrate folk tales for an Oslo zoologist P. Chr. Asbjørnsen – a productive professional engagement that continued for 30 years. It was in this period, that Kittelsen had illustrated fairy tales and trolls, as appearing in his 1899 classic edition of Norwegian Folktales. In addition to this work, he continued to paint and to produce lyrical prose with drawings that were published in Fra Lofoten (1890), Fra Lofoten II (1891), and Troldskap (1892).

35, 43–46, 48–49

38

Bear lying on its back , 1825

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on cardboard

Two German Sheperd Dogs , 1827

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on paper mounted on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Collection

44

Croak! Croak! , 1907

Illustration for Trangsviks posten , Vol. 3, No. 15

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Donkey with a Chair-saddle , 1820

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Wolf , 1828

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

The Little Elephant , undated Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Two Salmon , 1844

Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

A Wreck , 1900–1907

Illustration for Trangsviks posten , Vol. 3, No. 6

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

40 46

Aeolian Harp , 1905

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Olje på lerret Kode

In the Lion, s Den

John Savio

John Savio was born in 1902 into a Sami family – his father participated in the South Pole expedition. Upon the death of his parent, he had been raised by grandparents who were wealthy traders, reindeer owners and fisherman, that supported Savio’s middle education in Vardø where he became acquainted with the Sami member of parliament Isak Saba who became his teacher. Savio continued his education in Oslo where he attended the Norwegian National Academy of Craft and Art Industry. Throughout the 1920s, Savio travelled extensively throughout Norway to places like Karasjok, Lofoten, and Romsdal, although with meager means. In order to support himself, he traveled door-to-door selling his woodcuts of Sami folklore and cultural imagery. He continued to travel into Europe with exhibitions in Paris in 1936 where he received critical praise, although he died impoverished.

Traditional Sami spiritual practices and beliefs are tied to animism and the belief that connecting to the enrionment therein would produce great spiritual benefits. Under this framework, all bodies, human, animal or otherwise, are animated by a spiritual component or soul, which is endowed with intentionality.

Throughout the 17th century, Sami individuals were burned at the stake for practicing witchcraft in shamanistic traditions in using drums and practicing sacrificial rituals related to healing, fortune telling, finding lost objects, the absolution of sins, and

Rasmus Meyer Room 108 Rasmus Meyer Room 107

Standing Clock, Régence Oak with intarsia

Kode, Rasmus Meyer Coll.

The Contemporary Bird Eben Selbius, who Sings with Others’ Beaks , 1912

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Taj Bag , 2008

Roe Ethridge (1969–)

C-print

Edition 1 of 5 + 2 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Mister Rheder Jørnsen and the Spitting Lama , 1900-07

Theodor Kittelsen (1857-1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Two Cousins , 1912

Theodor Kittelsen (1857-1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Big Cock 1 , 2020

Heji Shin (1976–)

Inkjet print

Edition 1 of 3 + 2 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Cormorants on Utrøst , 1912

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Untitled , 2008

Lari Pittman (1952–)

Del vinyl and aerosol enamel on canvas over wood panel

Erling Kagge Collection

Al Dente , 2003

Isa Genzken

Italien ceramic, lacquer, plastic.

Edition 41 of 74

Erling Kagge Collection

weather magic. Attempts at effacing these practices from the country continued through the early part of the 19th century, when Norway adopted policies to dislocate the Sami minority population, involving forced assimilation and language policies. Throughout the 1920s, if anyone wanted to buy or lease state lands for agriculture in Finnmark, families had to be fluent in the Norwegian language and due to schooling requirements schooling, many families had to abandon a traditional and nomadic way of life. 56–64

Woodcut Kode

Confirmands

( Rihppaskuvllas) , undated John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut

Kode

The Cult of Ruin

Woodcut Kode

Within the cultural landscape, nature is doubly and paradoxically connotative of both the dominant and the dominated. Adorno tells us that this conflict of meaning resides by a disenchantment with the world, constituted by an impulse, a motivation, a longing, an insistence. With the collapse of romanticism and the rampant introduction of industrialized capitalism, natural beauty becomes merely an image, as exemplified by now-kitsch icons, Matterhorn and purple heather: “natural beauty, in the age of its total mediatedness, is transformed into a caricature of itself.” With the stronghold of organized tourism, it is telling that in the 1960s, Adorno foresaw that a feeling for nature was starting to amount to a “moralistic narcisstic posturing

Lollipop (Soaddenjálggis) , undated John Savio (1902–1938) Girl (Nieida) , undated John Savio (1902–1938) Rasmus Meyer Room 106 61 59 60

Boys with lasso Gaudak suopanin (Gutter med lasso), undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Good weather (Shiega dolke) , undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Nærøy Fjord , 1834

Knud Baade (1808–1879)

Oil on cardboard Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Wolf Pair (Gumpe guoktas) , undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Lasso (Suopan) , undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Coffee Break (Káfe vuoššá) , undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Wolf and reindeer (Gumppet ja bohccot) , undated

John Savio (1902–1938)

Woodcut Kode

Moonlight , 1869

Knud Baade (1808–1879)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Rockaway (Spring‚ 08) , 2008

Roe Ethridge (1969–)

C-print

Edition 3 of 5 + 2 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

as if to say: What a fine person I must be to enjoy myself with such gratitude – then the very next step is a ready response to such testimonies of impoverished experience as appear in ads with personal columns that claim sensitivity to everything beautiful.”

In conclusion: “the essence of the experience of nature is deformed.”

Lars Hertervig

Hertervig had been born into poverty, his family adhering to Quaker traditions that valued essentialism and the pursuit of inner light. The Norwegian architectural theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz provides further insight with respect to this idea of light as specific to the Norwegian context: “the Norwegian term for weather (vær) is related to være (to be). ‘To be’ signifies being thrown into a changing and unpredictable world, i.e., a world that provides no fixed point of view, a world in which we are unable to accept the given and act freely.” 68–69, 74

Seascape , undated

Lars Hertervig (1830–1902)

Oil on canvas Kode

Forest Landscape , 1830

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Mountain Lake, undated

Lars Hertervig (1830–1902)

Oil on canvas Kode

Landscape with a church

Lars Hertervig (1830–1902)

Oil on canvas Kode

The Gulf of Sorrento , 1834

Thomas Fearnley (1802-1842)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Grindelwald , 1835

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Königssee in Bavaria , 1830

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Monte Vesuvio , undated

Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Peder Balke

Shipwreck

Peder Balke was revolutionary in the pictorial context within the context of 19th century landscape painting. His sea- and mountain-scapes were more attenuated and less lustrous than of his peers in the Romantic concept of nature. In his mature work, Balke rejected the view of nature as immense and unruly sublime, and opted instead for radically reductive, almost monochrome renderings. According to Per Kirkeby, Balke used “…an orgy of dirty tricks, worthy of any stunt painter: waves executed as marbling, sponge-dubbing, combing wet paint and whatever worked.” Kirkeby’s interpretation was not intended as critique, rather as a candid reflection upon Balke as an artist, staking out the modern by making painting transparent: “a wave is a wave, and already rolled to nothing, like so much water, and a painting is a painting.” Balke was, after all, working in the wake of an industrial age, after which trust in natural beauty had succumbed to its total mediation, in the form of pollution, exploitation, and commodification.

In this sense, Balke abandoned the meticulously executed composition and the blue and brown tones that predominated in his earlier work, to employ simpler techniques to capture light against darkness. The main forms are developed by the bold, sweeping movements of rags, course brushes, and even with his own fingers. His fingerprint is left as a mark that makes the artist’s process and presence transparent.

Balke’s unconventional techniques led contemporary critics to hold him in contempt. A review in Morgenbladet described the work at the time as:

“…devoid of all artistic interest – his paintings with terrible colors, just black and white and few garish touches of blue and yellow here and there, with no

Rasmus Meyer 105

Tree Lamp , 2020

Urara Tsuchiya (1979–)

Glazed stoneware Erling Kagge Collection

View across Fjord , 1859

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Eidsvoll Church , 1855

Joachim Frich (1810–1858)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Chest of drawers, Empire Mahogany with intarsia Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Waterfall , 1856

Gustav Adolph Mordt (1826–1856)

Oil on paper mounted on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Welsh Landscape , 1864

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Table clock, classicism Bronze Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Dying Trees , undated August Cappelen (1827–1852)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Bodensee, Bavaria , 1882

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

question of a grandiose, poetic perception; not even in the simplest technical requirements of drawing, perspective, clarity, strength, and depth of color have been observed. The fore and middle grounds appear to have been drawn with a ruler…”

Born on the island of Helgøya in Ringsaker in 1804, Balke was raised in a humble family, and developed a clear awareness of the disparity between social classes. Throughout his life, he was drawn towards the political, economic, and social realities of his time. Art provided him with the means to live a life free from servitude to the state. His compositional technique remained unusual for his time, and this eccentricity, coupled with his increasing activist role in the pursuit of workers’ rights, complicated reception of his work. He became the Chairman of the Workers’ Union in the 1850s, and was regarded as a radical idealist, set on improving the material and institutional conditions of the workplace. When he died, his obituary credited him as a socially aware and committed citizen.

Peder Balke went so far as to abandon the brush substituting his finger blending black and white pigment so as abandon color and grand scale, in feigning nature, to abstractly and reductively, attempt to convey its true force. 90

Richard Prince Cowboy

Richard Prince (1949) manipulates means and products of mass media from the American advertising culture of the late 1970s. During the 1970s and as an aspiring painter, Prince worked in the tear sheet department at Time-Life Inc.in Manhattan, helping to oversee several separate magazines. While there, Prince began to rephotograph those pages, often cropping the shots to obscure text or logos, intensifying their artifice. In doing so, Prince undermined the seeming naturalness of the images, revealing society’s desires as hallucinatory. Untitled (Cowboy) among his most renowned series as a deconstruction of an American archetype at a time, as profiled in the 1960s ad campaigns for Marlboro cigarettes. Prince’s Cowboy conjures another illusion, one specifically associated with the excesses of the 1980s and the conflation of materialism and nature as manifested by spectacle. That decade in America was defined by President Ronald Reagan who promoted neoliberal policies which largely benefitted the wealthy. A former Hollywood actor, Ronald Reagan was stage managed, acting out the role of a cowboy, appealing to a romanticized notion of masculine authority. 85

Untitled (Cowboy) , 2003

Richard Prince (1949–)

Ektacolor photograph

Edition 2 of 2 + 1 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

Mountain Landscape , 1892

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

From Asker , undated

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Forest Interior , 1873

Hans Gude (1825–1903)

Oil on canvas Kode

View from Bøverdalen , 1868

Johan Fredrik Eckersberg (1822–1870)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Ship in Surf , undated

Peder Balke (1804–1887)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Stenersen Collection

Oscar Tuazon

Wreck

Oscar Tuazon (1975) is a sculptor who works with natural and industrial materials to create objects, structures, and installations that can be used, occupied or otherwise engaged by viewers. With an interest in deconstructivist architecture, Tuazon produces environments that reconnect humanity’s connection to habitat and objects that promote reflection upon the potential of architecture digressing from its allegiance to the Fordist values of global capitalism. 91

Seth Price

Mother and Child

Mother and Child is composed of yew wood, one of the oldest native tree species in Europe, and also attributed as a symbol of death and doom as it also provides shelter and food for woodland animals. It is coated with diamond acrylic plastic, a bulk industrial material used for plastic sheeting and multiple uses. Price integrates industrial plastics for a host of cultural associations, including as symbolic of modernism’s belief that technological progress may be an embodiment of the modes of production, distribution & proliferation, collapsing the distinction between the handmade/organic and the massproduced. 92

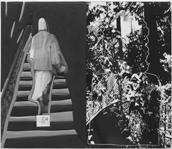

Klara Lidén

Paralyzed

Klara Lidén’s Paralyzed, an uninhibited dance performed on the metro in Sweden, reflects futility as a pervasive condition of contemporary life. Helen Molesworth has written of the work that Liden is doing damage to her own property, rather than to other people’s, and that in doing so she is doubtlessly making her daily life just ever so slightly more difficult.” The soundtrack in Lidén’s film is Paralyzed, by Legendary Stardust Cowboy, an outsider to be a musician who considered to be incapable of playing an instrument, singing in tune, or keeping in time. Released in 1966, the song was considered unintelligible, even said to be one of the worst songs ever recorded. Despite this labeling, the song made “the Ledge” a cult figure. In 1973, a team of NASA Mission Control technicians picked the song to wake up members of the astronauts aboard the Skylab space station, who, in turn, found the song so disruptive that they forbade it from ever being played again on any mission. 94

91

Wreck , 2007

Oscar Tuazon (1975)

Folded digital C-prints

Edition 2 of 2 + 1 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

94

Paralyzed , 2003

Klara Lidén (1979–)

DVD

Edition 10 of 10 + 1 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

92

Untitled (Mother and Child) , 2008

Seth Price (1973–) yew wood and diamond acrylic plastic

Erling Kagge Collection

93

From Königsee, Bavaria , 1832

Thomas Fearnley (1802-1842)

Oil on cardboard Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

Rasmus Meyer Room 104Significant Others

Gerhard Munthe

Sigrun Sandberg Munthe

Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929) was a landscape painter who played a pivotal role in the 19th century revival of pictorial tapestry in Norway. Bewitchment – the transformation of one world to the other – was a common theme both in folk tales at the time and in Munthe’s tapestries. From the 1890s into the 1920s, Gerhard Munthe designed many weavings with images of underworld creatures and scenes of people being bewitched. However, it was in 1888, that Munthe designed his first tapestry for his wife Sigrun Sandberg to weave. Sigrun Sandberg Munthe (1869–1957) was inspired by traditional weavings that she saw in farmhouses in the countryside where Gerhard had been painting and she continued to weave many of his watercolors into designs including Three Princesses (1905). The theme for the tapestry may be a reference to The Three Princesses in the Blue Mountain - a tale which begins with three sisters, normally kept inside the castle walls for their protection, successfully pleading with the guard to let them into the garden. They collect beautiful flowers in the afternoon sun, but after picking a large rose are swept away on a snowdrift. There were other weavers who realized Munthe’s designs including Augusta Christensen, the head of the weaving school at the National Museum for Art and Design in Trondheim, and the first weaver after Sigrun Sandberg to translate Munthe’s watercolors into woven wall hangings. Later tapestries had been woven also by Ragna Breivik.

95–96, 99, 101, 175

97 95

From Elverum , 1879–80

Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

98

Landscape with cattle , 1870

Anders Askevold

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

The Proposal , 1873

Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

96

The artist‘s home in Elverum , 1880

Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

99

The Fairy Garden , c. 1894

Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929) and Sigrun Munthe (1869–1957)

Tapestry, wool Kode

Study Head, An Italian , 1842

Adolph Tidemand

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

100

Rock and Heather , 1862

Anders Askevold (1834–1900)

Oil on cardboard

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

101 Rasmus Meyer Room 103Isabella Ducrot (1931) is an artist devoted to woven cloth as the founding material of her artistic practice. Earlier in her artistic career, Ducrot assembled a collection of antique textiles from her travels to Asia, primarily from Turkey, India, China, Tibet and Afghanistan. Her first source of inspiration comes from the weft of these fabrics, with the aim to reveal the original architecture of the material, composed of crossing threads and voids. Works like Tendernesses portray godlike figures inspired by Persian miniatures, or Pots, still life arrangements made on parchment like sheets of handmade paper and thin cotton, to reflect the artist’s enduring interest in pattern, and in the capacity for memory and narrative to be refracted into schematic form – ‘rewoven’, that is, via an array of repeating marks and motifs. 103, 105, 212

Ann Cathrin November Høibo follows a simple pattern of warp-and-weft in weavings are part of a lineage of textile art within her native Norway. Mentored by Else Marie Jakobsen, the pupil of Hannah Ryggen, to Frida Hansen who established the Workshop for National Tapestry Weaving in 1892– to follow in the tradition of weaving with respect to social, political coordinates.

Prunella Clough

Prunella Clough (1919–1999) started out her career working in mapping and graphic design for UK’s Ministry of Labour before she committed to painting in the early 1940s. Among her first works to be exhibited, Equinox from 1947 designates the line in the year when the Earth’s axis is tilted neither toward nor away from the sun and also denoting a new start in astrology. It was also the year in which provisions for self-governing Pakistan and India came into existence. Throughout the 1950s and onward, Clough found subjects for her paintings in London’s industrial wastelands and bomb sites, docks, power stations, factories, and the scrapyards of the city. The painter described her forays into what she described as “collected awkward facts” as reassembled into paintings to hover between figuration and abstraction. As she noted: “art is as realistic as activity and as symbolic as fact.” 106, 134, 181

102

Staircase in the Rosendal Manor , 1903

Marcus Grønvold (1845–1929)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

105

Small Tendernesses II , 2022

Isabella Ducrot (1931–) Collage, pencil and pigment on Japan paper

Erling Kagge Collection

108

Untitled , 2014

Ann Cathrin November Høibo (1979–) Textile Erling Kagge Collection

103

Teiera Verde IV , 2019

Isabella Ducrot (1931-) Collage, pencil and pigment on Japan paper Erling Kagge Collection

106

Equinox , 1947

Prunella Clough (1919-1999) Oil on canvas Erling Kagge Collection

104

Kitchen Interior , 1879

Frits Thaulow, (1847-1906)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

107

Untitled (Jar) , 2003

Wolfgang Tillmans (1968-) C-type print Erling Kagge Collection

Wolfgang Tillmans

The Body Politic

The early period of the Industrial Revolution was one which evolved the body politic – that is the body that had previously been linked to the natural (and the supernatural) became merged with political economy on various levels – a body politic that was interwoven with the social relationships of production and reproduction. Donna Haraway has written extensively around this topic in “Animal Sociology and the Body Politic, 1978.” As early capitalism evolved, the body politic became separated from natural knowledge – the body, that is, split away and increasingly alienated from the understanding of the human and the interplay of the surrounding world in the satisfaction of organic and social needs to succumb to systems of control that was embedded in the marketplace. Sex gets equated with affliction, something that is physically and psychologically stressful, damaging, what it is to bear the mark of others. Sex is pain and a somatic phenomenon. 107, 136

Christian Krohg

In the 1890s, neither Oslo nor Kristiania could be called metropolitan – rather, these were bourgeois provinces of about 135,000 inhabitants situated in among Europe’s least developed countries. In 1890, Knut Hamsum published Hunger (Sult) as a semiautobiographical chronicle of physical and psychological hunger experience by an aspiring writer in late 19th century. Marx has addressed hunger in Capital (1869) that suggested that physical want was an integral element of the labor market. The book also spoke to the collision of metropolis and mental life. Sex reform as a wider movement of social reform took hold throughout Europe at the start of the 20th century –one that reflected a public debate around equal rights for women and men, as well as for those historically marginalized on the basis of their class or sexual orientation. Norway was at the forefront of those early reforms as reflected in the more radical position on the part of the cultural community referred to as Kristiania bohemen located in contemporary Oslo. Following Henrik Ibsen’s address of such unspoken topics as venereal and sexually transmitted diseases in Ghosts (Gengangere, 1881), an emerging Norwegian literary and artist community generated wider discussions around the legalization of prostitution as proposed by the Kristiania Arbeiderforening (Kristiania Workers’ Society) in 1882. The writer Hans Jæger published the novel From the Kristiania Bohemia in 1885, a story that

109

Twelve Different Courses

Illustration for “ Trangviks posten Vol. 3, No. 16

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

112

Mr. Jens Træby , Illustration for “ Trangviks posten Vol. 3, No. 9, 1907

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

115

Wedding Procession Through the Forest , 1873

Adolph Tidemand (1814–1876)

Oil on canvas Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

110

No Title ($5000 for the) , 1983

Raymond Pettibon (1957–) pencil and ink on paper Erling Kagge Collection

113

Safe , 2006

Kirsten Pieroth (1970–) Safe tipped forward Erling Kagge Collection

116

The Devil at the Feast , undated Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914)

Pen and pencil on paper Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

111

No Title (She made no) , 2001

Raymond Pettibon (1957–) pen and ink on paper Erling Kagge Collection

114

Operetta , 2006

Lari Pittman (1952–) Cel vinyl and aerosol enamel on gessoed canvas over panel Erling Kagge Collection

117

Struggle for Survival , 1889–90

Christian Krohg (1852–1925)

Oil on canvas Kode

recounts the experience of two young men in relation to dominant social and sexual mores of the time. The novel marked Jæger’s foray into sexual liberation and social justice. A year later, the painter Christian Krohg published Albertine, a novel that referred to prostitution as a way to tell of the greater exploitation of the lower classes by the Oslo bourgeoisie.

By 1910, the rights recognized onto women by the Norwegian state were progressive by international standards. Married women in Norway were among the first in Scandinavia to hold independent legal status, and by 1913, they gained the right to vote in national and local elections, marking Norway as the first state within Europe to do so. In this way, the pursuit of civil, social, and political rights had been inscribed into the political agendas of the Labor Parties to reflect what Herbert Marcuse would refer to as an aim to develop “a social wealth for shaping man’s world in accordance with life instincts.”

The Women’s Federation of the Labor Party (Arbeiderpartiet) had campaigned as early as 1901 for sexual reform to arrive as a key political issue build into the sovereign statehood of Norway. The movement’s key protagonists – Elise Ottesen Jensen and the feminist Katti Anker Møller, each lobbied for the emancipation of motherhood by facilitating welfare benefits for mothers and for assistance for single mothers. The political activist Henrik Berggren as part of the Norwegian Youth Socialists, was noted for Kärlek Utan Barn (Love without Children) a speech that landed him with a short prison term, and contributed to the adoption of a law that made any lobby advocating birth control illegal. Nevertheless the continued efforts of Ottesen Jensen and Anker Møller continued to lobby for the legalization of abortion so that motherhood was a voluntary choice, and to educate young women as to reproduction and birth control. Ottesen Jensen made these views public authoring a column within the Swedish newspaper, Arbetaren, that reached out to a larger community that included Käthe Kollwitz, a German artist and activist for worker’s rights in Germany. A feminist and socialist, Kollwitz was deeply influenced by August Bebel’s pioneering treatise on feminism – Woman and Socialism (Die Frau und der Sozialismus, 1879). These sociopolitical achievements on the part of the early women’s movements, and which had been part of the wider political agenda for statehood as a social democracy, were eventually challenged by a the widening rift between socialist and non-socialist women, following the Soviet revolution in 1917. The project of early feminism was also hindered further by the introduction of psychoanalysis and cinema – both disciplines imparting new perspectives in relation to interiority and in placing women, once again, in subordinate roles. 117, 161, 164, 188, 191, 193–195

118

Young Girl in the Lap of Death, from the series Death, 1934 Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Crayon lithograph

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

121

Death is recognized as Friend, from the series Death , 1937

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Crayon lithograph

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz was an artist who expressed a political commitment to social change that reflected the changing political landscape of her time. She gained recognition through her series, A Weaver’s Uprising (Ein Weberaufstand) in 1898 followed by The Peasants’ War (Der Bauernkrieg) series (1902–1908) which further demonstrated her commitment to the plight of the oppressed and disempowered. The Peasants’ War served as a sociopolitical pictorial manifesto that depicted strong female figures, leaders of a revolt. Kollwitz’ portrayal of women in acts of suffering, rebellion, revolution, became prominent at a time after when World War I was dramatically changing the lives of women. 118–123

119

A Mother protecting her Child against Death, 1934 Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Lithography

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

122

Woman Entrusts Herself to Death, from the series Death , 1934

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Crayon lithograph

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

120

Death on the Road, from the series Death , 1937

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Crayon lithograph

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

123

Death in a Crowd of Children, from the series Death , 1934

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Lithography

Kode, The Stenersen Collection

1st Floor

Rasmus MeyerThe Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss wrote Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: A Philosophical Approach in 1977 as a treatise to connect ecological concern with self-realization to become synonymous with “deep ecology.” Næss argued for the individual to see themselves as part of nature rather than separate from it, to care for the “environmental self.” He advocated for an understanding of things in nature as part or extensions of the individual, and in positing one’s authentic being in nature as a key part of one’s selfrealization. Næss drew from two key thinkers – Erich Fromm and Baruch Spinoza. Whereas from Fromm, Næss drew the idea an authentic love and care for ourselves will inform our concern for the environment, from Spinoza, Næss culled the need to strive for self-realization, as a way to integrate environmental concern into the development of what it is to be human. For Næss, he made no distinction between those who wanted to cultivate a garden and those driven to wild places in nature. His own preferred place was a mountain hut above the timberline beneath the Hallingskarvet Mountain in central Norway –a three-hour walk from the closest train station.

Erling Kagge regards Arne Næss a teacher. Having located a stripped-down cabin on the mountain range upcoming book on the subject of the Arctic, he is reminded of the sentence that Naess iterated to him – that “philosophically there is a chasm between the impossible and the fantastically unlikely.” And if Naess proposed to Kagge that, “two plus two can equal five if something changes,” that was enough to motivate Erling to keep walking and climbing, beyond the reasonable limits of human habitation.

Although Rasmus Meyer may have been unfamiliar to the writings of Næss, he was closely connected to gardens having been trained as a gardener. He designed a large park at his summer residency at Åstveit in addition to designing a city garden in Fjellsiden, with a preference in cultivating different types of tulips. That he decided to end his life in the year of 1916 referred to his Norwegian history as “when the dead was calling” is not a story told.

In this botanical room, the two meet for the first time, as Alex and Lutz, piggybacking one atop the other within the makeshift winter garden.

Nobuyashi Araki

Flowers figure into Araki’s work as symbols of Eros and Thanatos. Having been raised nearby Jyokanji temple in downtown Tokyo, a place where spirits of courtesans from Yoshiwara were enshrined, Araki used to watch the cut flowers offered at the graveyards. To Araki, arranging decayed flowers is a form of revival, and photography records the beauty of brevity as eternal in Eros, representing the confluence of all those tendencies within us that aim to preserve life, and Thanatos, representing the impulse toward death, as central forces in human existence. 126

Frida Hansen

Frida Hansen (1855–1931) was a Norwegian artist who had been trained by prominent artists such as Kitty Kielland in private lessions. Earlier in her career, she was an avid gardener and as an artist who sourced dyes for color palettes and scents for her textiles from the flowers and plants in gardens. In the early 1870s, when she and her husband faced bankruptcy during the economic depression, she learned how to weave and in 1890, she established a thriving business in the Studio for Handwoven Norwegian Tapestries. Later, she opened the weaving studio in in Tullinløkka in Oslo in 1892 for the wider production of textiles with a team of assistants. During this time, Hansen extended the studio into a teaching platform for women in weaving so that they might learn a trade and earn a living. Her commitment to such endeavors led her to weave a large scale tapestry for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, entitled Løvetann (Dandelion). The tapestry, which had been commissioned by the Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights, became an important symbol for the early women’s movement in Norway and for the expression of women’s struggle against oppression. In 1897, Hansen patented a special technique for weaving transparent tapestries – wool weft for the pattern would be woven on the warp of plied wool, leaving portions of the warp unwoven and allowing light to transmit through the open thread designed for textiles as room dividers and curtains. Hansen went on to receive critical acclaim for the tapestry Melkeveien (Milky Way) at the Paris Exposition in 1900. In 1897, Hansen established the Norwegian Rug and Tapestry Workshop – later renamed The Norwegian Tapestry Studio (DNB), which would become one of the most important weaving studios in Europe. 127–128

Marc Camille Chaimowicz

Marc Camille Chamowicz (1947) explores the dissolution of boundaries between art and design and between the public and private. Born in Paris in 1947, he was drawn to the interiors of Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard in his home city for their embrace of the decorative and the domestic. Inspired by his mother who had been a dressmaker in the couture House of Paquin, he was motivated to work within the spectrum of textiles as both landscape and interior. Interested in the historical alignment of color with gender, Chaimowicz explores what Johann Wolfgang Goethe projected onto girls and women with respect tints and shades: “The female sex in youth is attached to rose color and sea green, in age to violet and dark green.” Through emphatically colored, ornamental prints and objects, the artist explores femininity as fantasy aligned with what Simon de Beauvoir would characterize as “all the fauna, all the earthly flora: gazelle, doe, lilies and roses, downy peaches, fragrant raspberries … precious stones, mother of pearl, agate, pearls, silk.” Chaimowicz is received as an understated pioneer who examines intimacy and domesticity, to explore a broad visual language that includes wallpapers, screens and curtains with paintings, collages and wall murals, and ceramics. He has noted: “We should resist the tyranny of linear time for one which is much more elusive, labyrinthian, gracious and once understood, perhaps even kindly. Once we recognize that it can fold in on itself – wherein, for example, recent events can seem distant and more distant ones seem closer – we then have a greater fluidity of means.” 129

Prunella Clough

Prunella Clough (1919–1999) started out her career working in mapping and graphic design for UK’s Ministry of Labour before she committed to painting in the early 1940s. In the the 1950s, Clough found subjects for her paintings in London’s industrial wastelands and bomb sites, docks, power stations, factories, and the scrapyards of the city. The painter described her forays into what she described as “collected awkward facts” as reassembled into paintings to hover between figuration and abstraction. As she noted: “art is as realistic as activity and as symbolic as fact.” 135, 182

124 125

Portrait of Rasmus Meyer, 1930

Hjørdis Landmark (1882–1961)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

June, 1918

Frida Hansen (1844–1931)

Tapestry, wool

Kode, West Norway Museum of Decorative Arts’ collection

Untitled #398 , 2008

Haris Epaminonda (1980–)

Polaroid

Erling Kagge Collection

Bluebells , 1901

Frida Hansen (1844–1931)

Det norske billedvæveri

Tapestry, wool

Kode

Untitled

Nobuyoshi Araki (1940–)

1 color print

approx. 100 x 120 cm

Erling Kagge Collection

129

After PB. (1) , 1985–1990

Marc Camille Chaimowicz (1947–)

Oil and charcoal on board and canvas

Erling Kagge Collection

Bing & Grøndahl

Bing & Grondahl was a Danish porcelain manufacturer founded in 1853 by the sculpture Frederik Vilhelm Grøndahl and merchant brothers Meyer Hermann Bing and Jacob Herman Bing, who were art and book dealers. In 1889, Grøndahl won the Grand Prix prize during the universal exhibition in Paris. The technique realized by Bing & Grøndahl invented by Fanny Susanne Garde and Effie Hegermann-Lindencrone, included an underglaze that provided for the application of the enamel before cooking so as to avoid a second cooking of porcelain. The technique resulted in shades comparable to the transparent colors achieved in a watercolor. Garde and Hegermann not only developed the signature underglaze for Bing & Grøndahl, but in sharing a studio in the factory, they became the female exceptions to work that had been traditionally to men. 131

Fanny Susanne Garde

A Danish porcelain painter who graduated in 1876 from the Arts and Crafts School for Women in Copenhagen before working as an artisan at Bing & Grondahl. Her first projects included decorating the company’s Heron dinnerware set, rendered by the underglaze painting technique. Garde’s signature work had been vases decorated with flowers or fruits, sometimes working with crackle-glazed porcelain. 130

Effie Hegermann-Lindencrone

Effie Frederikke Nicoline Octavia HegermannLindencrone (1860–1945) was among Denmark’s most notable porcelain artists who studied at the Arts and Crafts School for Women in Copenhagen. It was here that she met Fanny Susanne Garde who would become her lifelong partner. She committed her entire professional career to decorating porcelain for Bing & Grøndahl’s factory. She adopted the Art Nouveau style producing works that sculpted forms replicating aquatic plants, seaweed, birds and fish into the porcelain work. Her work is included in the collections of the National Gallery of Denmark, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and at the Art Institute of Chicago. 132

130

Vase, ca. 1900

Fanny Susanne Garde, Bing & Grøndahl Porcelain Kode

133

Vase, 1918

Fanny Garde, Bing & Grøndahl

Porcelain Kode

Alex & Lutz am Strand , 1992

Wolfgang Tillmans (1968–)

Chromogenic print

Edition 8 of 10 + 1 AP

Erling Kagge Collection

131

Vase, 1897-1900

Effie Hegermann- Lindencrone, Bing & Grøndahl Porcelain Kode

134

Snow Melt , 1987

Prunella Clough (1919–1999) Watercolor and collage on paper

Erling Kagge Collection

132

Vase, ca. 1908

Effie Hegermann- Lindencrone, Bing & Grøndahl Porcelain Kode

135

Snowfall From the Roof , 1900–1907

Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914) Ink on paper

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

136Tosh Basco

Tosh Basco rose to prominence in the drag scene in San Francisco in the 2010s. Known for her movementbased performances under the name Boychild, Basco’s photography and drawing accompany the performance practice. Viewed as a whole, Basco’s work attempts to enfold language, becoming, and representation together in spaces where they are presumed to exist as discrete entities. 137

Laura Owens

Over the past 20 years, Owens has created a body of work that examines painting as a process and its visual possibilities. Throughout the 1990s, Owens became known for figurative compositions that drew from decorative motifs, Shaker furniture, Japanese kimonos, Chinese tapestries, tulips, hyacinths, and daffodils rendered in the traditions of abstraction of neo-geo, Color Field, and pattern painting. 139

Farah Al Qasimi

Farah Al Qasimi has spent the last decade documenting the Persian Gulf, focusing on images of objects within interiors located within the region where she was raised, as a way to enter into a social critique of the structures of power, gender, and social norms in the Gulf Arab states. 138

Rasmus Meyer Room 201

Caves and Vortices: The Centrifugal Force of History

As inferred by Walter Benjamin, the lives of collectors are imbued by a “dialectical tension between the poles of order and disorder” – with an ambiguous relationship to ownership and to a mysterious relationship to objects that do not, as the author notes, emphasize a functional or utilitarian value, but nevertheless an intimate one. What is it for someone to enter into some private realms to infer a transgression as a type of violence – to pull apart and interrupt narratives and to established orders of registration and presentation, to usurp memories for the development of another plot. Although this strategy was canonized by artists as came institutional critique of one sort of other, the organic cooperation interpenetration of the historical and contemporary world tends to be,

137

Tangle (bouquet) , 2022

Tosh Basco (1988–)

Oil, pastel, and pigment on paper

Erling Kagge Collection

138

Dragon Mart Still Life 6 , 2023

Farah Al Qasimi (1991–)

Inject print on Canson Cotton Rag 210g

Edition of 50 + 5 AP

Erling Cagge Collection

139

Untitled , 2004

Lara Owens (1970–)

Watercolor, gouache and acrylic on paper

Erling Kagge Collection

140

Peat Marshes at Jæren , 1898

Kitty Kielland (1843–1914)

Oil on canvas Kode

141

Landscape from Jæren , undated

Kitty Kielland (1843–1914)

Oil on canvas

Kode, The Rasmus Meyer Coll.

142

Reading Girl , undated

Unknown artist ( assumed early work by Harriet Backer [1845–1932])

Oil on canvas Kode

justifiably, restricted by regimes of conservation and preservation. Although it would be sufficient to write that such standards all too often become the default settings for the bureaucratic technocracies of museums, academies and schools, to simply, as Bartleby would put it, “to prefers not to.” Yet, it is this jarring opening up from a vaulted stance, the encounter of rhetoric of yesterday to meet the banter of the present, as a meeting ground for reconciliation and re-negotiation. The privileging of such encounters could allow art to stumble along paths where it may have no right to be to seek a wider field of correspondence, because it is, as Theodor Adorno wrote: “it is self-evident that nothing concerning art is selfevident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” This, to the effect, historical trauma persists, and collective experiences of trauma persist, so as to enforce the centrifugal force with which history bleeds into the present.

Gustave Courbet