39 minute read

CHAPTER EIGHT

IN TERMS OF BOTH ITS LOCATION AND AGE, UBC WAS INDEED A UNIQUE UNIVERSITY AT THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM. SITUATED AT A GATEWAY TO THE PACIFIC RIM, IT WAS NOW WELL CONNECTED TO ASIAN NATIONS WITH EMERGING ECONOMIES, AND TO MAJOR RESEARCH UNIVERSITIES SIMILARLY ON THE FOREFRONT OF KNOWLEDGE AND TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT. IT WAS OLD ENOUGH TO HAVE ITS OWN TRADITIONS, BUT YOUNG ENOUGH TO BE NIMBLE IN RESPONSE TO MODERN NEEDS, INCLUDING PLAYING PROMINENT ROLES TO SUPPORT CANADA’S ECONOMY AND TACKLE THE WORLD’S SOCIAL ISSUES.

President Martha Piper insisted from the outset of her nineyear tenure that UBC was capable of “stepping up” to both the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, and bore a societal obligation to do so.

By her second term, Piper’s inherent gifts as a communicator and almost evangelical commitment to lead UBC to the upper echelons of global academia had garnered widespread attention among other universities, particularly with other member-institutions of the prestigious Association of Pacific Rim Universities and those of Universitas 21, a coalition founded in 1997 as “the leading global network of research-intensive universities.” Piper had also been instrumental in building substantial connectivity to industry and to government at both the provincial and federal levels. The university’s growing influence was exemplified by its Public Affairs office, which operated

Martha Piper is pictured speaking at the announcement and launch of the BC Knowledge Development Fund in 1998. Piper was influential in convincing governments at both the federal and provincial levels to provide funding for research talent and infrastructure at universities across Canada, and in particular for the establishment of the Canada Research Chairs Program.

at an ever-accelerating pace in response to journalists from across the nation who had come to regard UBC as an important source for expert analysis on an expanding range of subjects. The University-Industry Liaison Office worked at a similarly feverish pace supporting research contracts and start-ups, with over 90 companies having been spun off by the turn of the millennium as a result of UBC research. The growing list of private and publicly traded companies underscored Piper’s oft-stated contention that research universities had become powerful engines of economic growth.

As the 21st century unfolded, research funding at UBC was on the rise, its endowment fund was continuing to grow, and international student enrollment figures increased steadily, as did the ranks of research-oriented faculty members from Canada and abroad. Not perhaps since the growth years following the Second World War was the mood more buoyant and bullish within the university community, nor more cohesively focused on the future, thanks to the university’s strategic plan, Trek 2000 and its update Trek 2010, that jointly emphasized not only ambitious learning and research objectives, but also strong commitments to the community and to international imperatives. Within this context, the future of the School of Kinesiology was more promising than ever, built as it was upon a strong foundation of programs, students and faculty, including

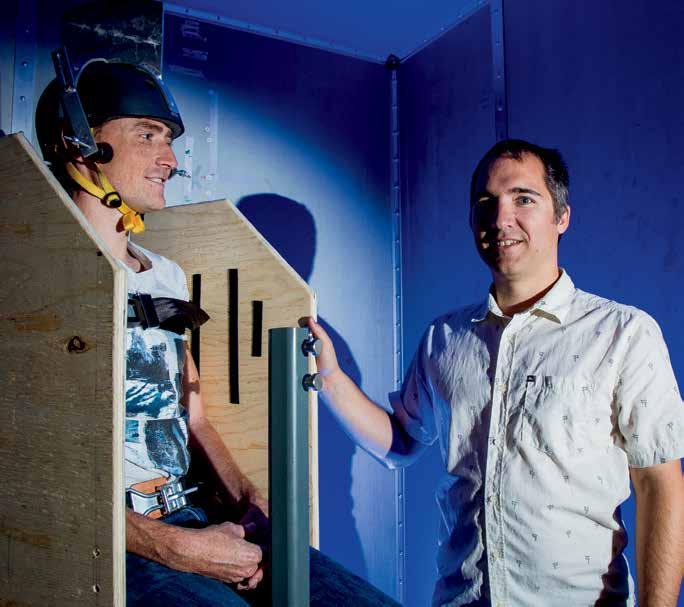

Bob Sparks arrived at UBC in August of 1980 and began his 37-year academic career with a full-time post that consisted of a combination of fifty per cent assistant professor in the School of Physical Education and Recreation and fifty per cent as University Diving Officer. His many contributions to UBC and to the school included 11 years as director, during which time his collegial leadership resulted in a unified strategy to usher the school on the final leg of a decades-long journey into the upper echelon of kinesiology learning and research in Canada.

talented researchers with the capability to attract funding from all of the federal granting agencies. But the heady time was not without its challenges, which were primarily three in number. The first was the need to replace the ongoing faculty retirements by recruiting more of the right people to continue the decades-long evolutionary journey. The second was the lingering and now acute need to establish a modern building to replace the aging infrastructure of War Memorial Gymnasium and Osborne Centre, and to congregate faculty members and students in an atmosphere that was interdisciplinary, interactive and international in scope. The third was to appoint a director who understood the school’s current culture and strengths, and could also see a way toward the exploration of new frontiers of research and learning. As it turned out, those involved in the search determined that the leader they needed was already within their own ranks.

Robert Ellsworth Coffey Sparks grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, where his father, Ray Sparks, was a professor and wrestling coach at Springfield College – the very institution whose curriculum had intrigued Bob Schutz in his student years – and later worked for the US Defense Department as director of physical education and health for the US Dependents Schools European Area. During his high school years, Bob Sparks was active in sports and spent summers as a counselor and mountaineering instructor at International Ranger Camps based in Leysin, Switzerland. He ran cross-country and track during his first two undergraduate years at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, and then spent a junior year abroad in Paris. He graduated with a BA in French in 1968 after completing two summer courses at Springfield College. But as the war in Vietnam escalated, he correctly anticipated that a diversion in his path was inevitable. His draft notice arrived in July of that same year, prompting his voluntary enlistment in the US Navy in lieu of induction in the Army.

He underwent basic training at Great Lakes, Illinois, followed by a course in electricity and electronics, after which he was assigned to Bainbridge, Maryland for radioman training. He was then assigned to Coronado, California for naval special warfare training, which encompassed a wide range of disciplines

Appointed in 2001, Brian Wilson’s interests revolve around environmental issues, peace, social movements, consumer culture, media, youth, qualitative methods, and sport and leisure studies generally. His most recent research includes studies on how stakeholders in the golf industry and mega-event organizers respond to environmental concerns; the role of bicycles in development efforts, and how sport-related social and environmental issues are covered in the media. Brian is also director of the School's Centre for Sport and Sustainability.

Laura Hurd Clarke’s research examines how older adults’ perceptions and experiences of their bodies are shaped and constrained by age and gender ideals and norms, health and illness, healthism, disability, media representations, and their social position, including culture, ethnicity, sexuality, and social class. Her work is funded by SSHRC and includes consideration of the self-care and health promotion practices of older adults, their use of mobility technologies, sexuality and body image in later life, and media representations of aging.

and skills including underwater diving. He subsequently went through airborne parachute training at Fort Benning, Georgia and then deployed to Vietnam in 1970 where he received a Navy Commendation Medal for valour in combat and a Purple Heart after being wounded. On return to Coronado, he instructed free fall parachuting for Naval Special Warfare Group and served as a member of the US Navy parachute exhibition team.

A year after completing his enlistment and leaving the Navy, he earned a commercial pilot’s license. Aware of the often shortened careers of airline pilots owing to stringent medical requirements, he simultaneously gave thought to a back-up plan as a teacher, either in flight schools or public education. Encouraged by his father, who had contacts at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (UMass), he met with the university’s head of sport studies who offered him a full scholarship and teaching assistantship in their general physical education program. Easily tempted by the offer, he enrolled in a master’s program at UMass Amherst in 1973, where he taught scuba diving, rock climbing and an outdoor adventure course. Utilizing his extensive experience in adrenaline pursuits, his thesis was titled “High risk sports: A philosophical investigation.”

He entered the PhD program at UMass in 1976, and continued to teach outdoor education courses and scuba diving including extension courses offered in the Caribbean under the auspices of a non-profit organization he founded called Project DEEP (Diving Education Extension Program). Remarkably, he also continued advanced flight training and eventually completed a commercial flight instructor instrument rating. It was at this time that he received a letter from a former diving student with an advertisement from the Chronicle of Higher Education for a diving officer position at UBC. He wasted no time in applying for the position and promptly received a call from Professor Bob Scagel, head of botany, asking when he could come for an interview.

“I was in North Bimini, Bahamas at the time teaching a Project DEEP sport diving course, and barefoot with long hair,” Sparks recalled. “I agreed to come as soon as possible and flew back to Massachusetts where my future wife, Kathy Guild, gave me a haircut and sent me on my way. It was a great interview, and I met a remarkable person, Bob Morford, with whom I identified straightaway as a kindred spirit. I stayed at Hal Lawson’s house for a few extra days and met several times with Bob. He and Hal wondered if I could teach the new Introduction to Sport Studies course the School had just developed. The contents fit well with the course work I had done at UMass and with my interests. My answer was a resounding, ‘yes!’”

In August 1980 the newlywed couple drove across Canada

to UBC where Sparks embarked on an academic career with a full-time post that consisted of a unique combination of fifty per cent assistant professor in the School of Physical Education and Recreation and fifty per cent as University Diving Officer (UDO), a position in which he was to co-ordinate, regulate and facilitate use of underwater diving as a research tool in the marine sciences. Katherine, meanwhile, enrolled in the UBC Faculty of Education master’s program in educational and counselling psychology.

During his first term of employment at UBC, he completed and defended his dissertation at UMass Amherst, titled “Intentional action in sport: A philosophic investigation” and was awarded his PhD in the spring of 1981. For the following six years he taught undergraduate courses in the school, conducted research in philosophy of sport and sociocultural studies and instructed underwater diving. Concurrently, in his capacity as UDO, he conducted “check out dives” for faculty and students, developed diving regulations for the university and helped found the Canadian Association for Underwater Science and the CAUS Standard of Practice for Scientific Diving. In 1987, however, a change in the UDO position resulted in it being no longer compatible with an academic position. Confident that Sparks had a great deal to offer, Morford wasted no time finding a way to appoint him full-time to the school, at which point he transitioned into mass communications, health promotion, sport sponsorship and marketing, in which areas he developed an active program of funded research.

In 1995-1996 he took a leave of absence and taught courses in sport management and conducted research as a senior lecturer in the School of Physical Education at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. It was to be a transformational move. “The position opened my eyes to the importance of leadership in university administration and gave me the opportunity to study the literature in this area,” said Sparks. “On returning to Canada, I decided to move into administration as the next phase of my career. I took the position of Associate Director Undergraduate Affairs for the School in 2001-2004, thinking this would give me leadership experience and help me prepare for a leadership post in Canada or the US.”

As it turned out, he didn’t have to look beyond the familiarity of Point Grey to secure a leadership position, as the opportunity arose at UBC when Peter Crocker stepped down as director of

Motor learning specialist Shannon Bredin is a leader in community-based initiatives in the field of physical activity, health and the prevention of chronic disease. She is the founding director of the Cognitive and Motor Learning (LEARN) Laboratory, whose research examines factors that influence human motor development, learning, and performance, with the overall goal of developing evidence-based tools, strategies, and standards for the development of healthy physical behaviour and expert performance across the lifespan. She is also director of the Laboratory for Knowledge Mobilization, which systematically evaluates available science in an effort to translate and disseminate evidence-based information across the spectrum of endusers for the promotion of physical activity, prevention of chronic disease, and the development of sport performance.

Exercise and sport psychology specialist Mark Beauchamp is a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar and the director of Psychology of Exercise, Health, and Physical Activity Laboratory. His research draws from diverse disciplines, including behavioural medicine, organizational psychology, and education, and is dedicated to understanding physical activity behaviour across the age spectrum and developing conceptually-sound evidence-based interventions that are cost-effective and sustainable. He also serves as the associate dean for research in the Faculty of Education.

the school in 2004. “Prior to applying, I spoke with a number of people and gave careful thought to what the School needed in a leadership capacity at the time. Based on this, I committed to an approach that would build on the very positive developments the School had undertaken in the new curriculum, the equitable workload provisions around teaching and research, and the new strategic plan based on Trek 2000.”

During and after his time at Otago, he became increasingly convinced that the optimal university leadership model had to be highly collaborative and distributed in nature, and one in which faculty members, staff and students would be invited to participate directly in the planning and operations of the school. The timing for a leader committed to this kind of thinking couldn’t have been better. Not only was Sparks highly respectful of his university colleagues, he was energized by the knowledge that as a collective they were more unified than perhaps ever before, particularly with respect to what the school’s future could hold in a world that increasingly embraced the importance of physical activity in health, and for what the school could contribute by sharpening its focus on human well-being. He also believed that such an approach would have to begin by focusing on members of the school themselves.

“One of the ways you create a strong, vibrant and positive organizational culture is to support your people and to make administrative processes transparent and accessible,” Sparks said in reflection upon the first months of his directorship. “I took it upon myself to be as personally transparent as possible. I told faculty, staff and students that nothing was off the table and they could ask me about anything I was doing. I was fully accountable and willing to talk.” To that end, he sought input for enhancing key administrative processes, including teaching mentorship and peer review guidelines, which were researched, developed, reviewed by committees of faculty members, and ultimately approved by the school in May of 2007.

He also targeted several key areas for renewal and development, using the literature he had studied at Otago on university

administration and models of organization that emphasized collaborative approaches. One of these was the organizational culture of the school. “Basically, I wanted to create a supportive environment among faculty, staff and students and make the School the best place to work, study and learn in Canada, and hopefully North America and the world.”

Above all, he was determined that the all-important task of hiring would be one in which all faculty members would be welcomed to take part. He engaged them to collectively identify strategic priorities and develop a hiring plan, with his task being to look for funding opportunities for the positions. At a retreat in December 2004, the school identified hiring priorities which coalesced into three positions: exercise nutrition, sociocultural studies, and sport and exercise psychology, although subsequent circumstances ultimately made it difficult to make appointments strictly according to the plan. Selection committees were convened for each position, the first of which was the psychology position which was filled by Mark Beauchamp, who had completed a PhD at the University of Birmingham, as assistant professor, exercise and sport psychology.

In 2005, Tim Inglis discovered a funding opportunity through the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation for five-year bridge funding to support a named professorship in spine biomechanics and neurophysiology. Even though this area had not been identified previously, there was support in the school that resulted in the appointment of recent Université Laval PhD graduate Jean-Sébastien Blouin, who was a post-doctoral fellow in the school at the time and held a doctorate of chiropractic, one of the requirements for the funding.

An opportunity to create a joint appointment in kinesiology and sports medicine arose during the hiring process in 2008 for an exercise physiology position. Sparks worked closely with Bob Woollard, head of family practice where the Division of Sports Medicine was located, and Gavin Stuart, dean of medicine to sort out the options. Ultimately, the Faculty of Medicine was able to cover one-third of the position and thereby enabled the school to appoint Michael Koehle, a practicing physician and environmental physiology expert who had recently completed a PhD in the school.

With laboratory instruction also identified as an area of concern, Sparks applied for and received competitive university funding in 2008 to support hiring two teaching faculty members and a laboratory technician, resulting in the appointments of exercise physiologist Maria Gallo and neuromechanical specialist Paul Kennedy to instructor positions and alumnus Rob Langill as a technician and lecturer. As encouraged as they were with the appointment of such promising talent in Prof. Jean-Sébastien Blouin leads a team of researchers in the Sensorimotor Physiology Laboratory to investigate whole-body human physiology. His specific research interests include characterising the physiological processes allowing humans to stand upright as well as the application of robotics and sensory approaches to probe the sensorimotor control of bipedalism and of the head and neck system. Specific research projects are directed to the mechanisms underlying the integration of multisensory information for human movement and to specific applications including the identification of neuromechanical risk factors for whiplash injuries and the related development of potential mitigation strategies.

Michael Koehle, a practicing physician and environmental physiology expert, completed his PhD in the school and was appointed jointly with the Faculty of Medicine in 2008. His funded research as director of the UBC Environmental Physiology Laboratory focuses on the effect of the environment on the cardiorespiratory system. This work includes the physiology and genetics of altitude illness and the interaction between exercise and environmental pollution. Through a combination of clinical work and research, his team also focuses on the prevention and treatment of other illnesses and injuries associated with exercise, including musculoskeletal issues, asthma and other respiratory conditions. In 2018 he succeeded Don McKenzie as the director of the Allan McGavin Sports Medicine Centre. Maria Gallo is an exercise physiologist specializing in leadership education for pedagogy and physical activity. A member of the Rugby Canada Hall of Fame, she is also the director of the Masters of High Performance Coaching and Technical Leadership Program. As a former national team athlete in rugby and bobsleigh, she is able to stimulate her students’ interest with real-life examples encountered in the realm of sport science. In her concurrent role as the head coach of the UBC Thunderbirds Women’s Rugby Team, she participates actively in the School’s evolving and strategically significant partnership with the Department of Athletics and Recreation.

Photo: Bob Frid

Photo: Rich Lam Paul Kennedy is a neuro-mechanical expert who specializes in engaging students in active learning processes. As part of his work, he has designed a curriculum that challenges the students and promotes dialogue on the concepts and principles inherent to the science of human movement, and encourages them to share their opinions, questions and concerns with teachers to create an optimal learning environment.

their midst, faculty members and students alike were increasingly stifled by the aging, inadequate and decentralized physical environments in which they were forced to work.

Sparks’ efforts to find a modern home for the school began in the first week of his directorship when he met with representatives from UBC Properties Trust and senior administration about the procedures for proposing a new building. These early steps began a long process of learning the ropes of central administration and working with other groups on campus that were in similar situations as the school, including nursing, occupational science and occupational therapy, population and public health, sports medicine, and the clinical research group in physical therapy. From this early work, there emerged a proposal for the Community Health Sciences Centre (CHSC) that would bring these groups together in a synergistic, incubator-type environment focused on interdisciplinary research, interprofessional education and knowledge mobilization concerning community health. In spite of his efforts as the project lead and the continued support of central administration, the CHSC concept ebbed and flowed but failed to become a reality, resulting in members of the school continuing to reside in scattered locations throughout the campus, and leaving unfulfilled the long-held aspiration to find a modern home.

The inaugural first-year cohort of students in the recently renamed UBC School of Kinesiology gather in the first week of September, 2011 to take part in Imagine UBC, a university-wide welcome and orientation day for entering students.

As Vancouver prepared to host the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, Bob Sparks seized the opportunity to have UBC involved in various research projects aimed at athlete performance under the umbrella of a national Games-focused strategy called Own The Podium and another called the Olympic Games Impact (OGI) project, a formal assessment of the economic, social and environmental impacts before, during and after the Games. Mandated by the International Olympic Committee, the OGI Project, along with a grant of $300,000, was awarded to the school under Sparks’ direction as principal investigator. The research was conducted by Rob VanWynsberghe, a lecturer in the school at the time, and subsequently an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education. The project grant agreement between UBC and the Vancouver Olympic Organizing Committee also provided a stimulus for establishing the UBC Centre for Sport and Sustainability in 2009 as a legacy of the Games.

Place and Promise

The appointment in 2007 of an international law and human rights scholar named Stephen Toope as UBC’s 12th president, along with the subsequent release of a refreshed strategic plan entitled Place and Promise, appeared to signal the start of a new evolutionary era in the university’s history. Keen to remain aligned with a plan that emphasized student learning, the school undertook bold new initiatives designed to enhance the student experience.

Chief among these was a long-held aspiration to develop a co-operative learning program for undergraduate students. Sparks applied for and received competitive university funding in 2008 to support the development of such a program, designed and inaugurated by Dave Sanderson, who was senior associate director, and Simone Longpré, who had been appointed as program coordinator. Next there came a staff position in student development to enhance the school’s student support programs, a role that was capably fulfilled by school alumna Robyn Leuty under the supervision of Sanderson. The next key step was the hiring of student peer advisors in the undergraduate advising office, under the guidance of Fran Harrison with support from Deborah Gromer.

A staff position in alumni development was created and filled by alumna Lindsey Smith who oversaw the start-up of a peer mentoring program in which alumni would mentor senior undergraduates about career development. Part of the rationale for the alumni coordinator position was to identify a network nationally and globally that graduates could draw upon for support, and to align with the university’s broader emphasis on alumni engagement.

As these structural pieces fell into place, Sparks could see new opportunities in the offing as Vancouver prepared to play host to the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. He began by holding a stakeholder meeting in 2006 with interested UBC faculty and administrators and representatives from the Vancouver Organizing Committee (VANOC) and 2010 Legacies Now about potential UBC involvement. This resulted in funding from the VP External and Legal Affairs Office to support an Olympic and Paralympic theme in departmental seminars across the campus, and a high profile Sport in Society series with five lectures that were podcast by The Globe and Mail.

Sparks also played a lead role in UBC involvement in various research projects aimed at athlete performance under the umbrella of a national Games-focused strategy called Own The Podium (OTP) and another called the Olympic Games Impact (OGI) project, a formal assessment of the economic,

social and environmental impacts before, during and after the Games. Mandated by the International Olympic Committee, the OGI Project, along with a grant of $300,000, was awarded to the school under Sparks’ direction as principal investigator. The research was conducted by Rob VanWynsberghe, a lecturer in the school at the time, and subsequently an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education. The project grant agreement between UBC and VANOC also provided a stimulus for establishing the UBC Centre for Sport and Sustainability in the school in 2009 as a legacy of the Games. Other faculty members also became involved in the Games, with Don McKenzie serving as chair of the Own The Podium Human Performance Awards Committee, Jack Taunton as the chief medical officer for VANOC, and Michael Koehle as a medical officer for Nordic events.

Modern Identity

On December 4, 2008 members of the UBC School of Human Kinetics met to take a vote on changing the name of the school. Prior to taking a formal vote, Bob Sparks set two conditions, the first of which would be that a two-thirds majority would be required for the name change to pass, and the second was that abstentions would count as a vote against. The voting members in attendance included two undergraduate student representatives, two graduate student representatives and 20 faculty members. After an extensive discussion, a motion was made to change the name to the School of Kinesiology. A count of the closed ballots revealed that 17 votes had been cast in favour and seven opposed with no abstentions, a result which met the two-thirds required majority. A problem, however, soon arose.

The Human Kinetics Undergraduate Society executive pointed out that in an online survey conducted prior to the vote, undergraduate students indicated they did not want to abandon the name Human Kinetics and expressed strong concerns that their voices had not been heard. Sparks immediately met with the students to review their concerns and search for a solution. Attempts were made by the school to revisit the issue with the Human Kinetics Undergraduate Society Executive in the spring of 2009, and again with the subsequent executive during the 2009-10 academic year, but to no avail. In the fall of 2010, however, a new executive indicated their willingness to hear arguments in favour of the name change and to conduct a second student vote, which culminated in an online ballot in early March, 2011 in which 92 per cent of students voted Exercise psychology specialist Guy Faulkner joined the school in 2015 with the distinction of holding a CIHR Chair in Applied Public Health. Faulkner leads the Population Physical Activity Lab which conducts research to address factors that cause or prevent physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour; to discover how participation in physical activity influences mental health, and how effective population-level physical activity initiatives can be designed, delivered and disseminated for public health.

Christopher Westaciendis velicaes ulparum quam, nam inctat vel maio quassim possint. Cuptumqui optatem que voloreictis magnit eum volenec tionse net maximint. Uptat. Qui rempos et etur, occus, tectiis erroribus, ullorepel idio. Axima nimaion pro od quis id qui quassit, consent ut utem ipient molorrunt, si t eum volenec tionse net maximint. Uptat. Qui rempos et etur, occus, tectiis erroribus, ullorepel idio. Axima nimaion pro od quis id qui quassit, consent ut utem ipient molorrunt, si t eum volenec tionse net

Emma McCrudden was appointed in 2016 to a newly created position evenly divided between the School as lecturer in sport and exercise nutrition, and the Department of Athletics as sport dietitian for student-athletes. She qualified as a dietitian from the University of Ulster, Northern Ireland and later completed a master’s degree at England’s Loughborough University in sports nutrition and exercise physiology. She worked at the English Institute of Sport from 2008 to 2013 and was the lead dietitian for Leinster Rugby of Dublin from 2010 to 2013. After moving to Canada she joined the Canadian Sport Institute and worked with national teams, including the women’s soccer and swim teams in preparation for the 2016 Olympic Games.

in favour of the change. The opinion was shared by graduate students, who just a few weeks earlier had met to discuss and to ultimately vote unanimously in support of the new name.

Based on the students’ support, a proposal was again brought forward to the School of Human Kinetics Council on March 24, 2011, and the name change to the School of Kinesiology and consequential changes in the names of the BHK and MHK degrees (to BKin and MKin, respectively), were approved by a 95 per cent majority, with 18 votes cast in favour and one opposed. The change of the name was then put forward by the provost at Senate on April 20, 2011 and approved. “It was a long process but it was worth the wait,” said Sparks, who was now in his second term as director. “In addition to approving the change, Senate conveyed congratulations for having listened to and involved our students.”

Having completed a final step in forging a new identity that accurately reflected the school’s current reality and future aspirations, the next critical task was to pay close attention to another upcoming round of faculty appointments. By this time the school’s popularity among entering students was a key factor in funding faculty positions, based on a new university formula whereby all faculty and program budgets were responsive to enrollment figures. With financial matters top of mind in both the school and across the campus, Sparks was determined that the approach to hiring would be as resolutely collaborative in his second term as it had been in the first.

Following an external review of the school’s outreach programs led by Sanderson in 2012, the school created an outreach manager position to support overall operations of the Active Kids and BodyWorks programs and a range of community initiatives.

Christopher Westaciendis velicaes ulparum quam, nam inctat vel maio quassim possint. Cuptumqui optatem que voloreictis magnit eum volenec tionse net maximint. Uptat. Qui rempos et etur, occus, tectiis erroribus, ullorepel idio. Axima nimaion pro od quis id qui quassit, consent ut utem ipient molorrunt, si t eum volenec tionse net maximint. Uptat. Qui rempos et etur, occus, tectiis erroribus, ullorepel idio. Axima nimaion pro od quis id qui quassit, consent ut utem ipient molorrunt, si t eum volenec tionse net A Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and Rick Hansen Institute Scholar, Chris West is an integrative physiologist with a primary focus on how the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems respond to spinal cord injury. He conducts research as director of the Translational Integrative Physiology Laboratory located at the Blusson Spinal Cord Center, which houses the International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries (ICORD). He was part of the International Cardiovascular Health Clinic that served at the London 2012 Paralympic Games, the Socchi 2014 Paralympic Winter Games and a number of world championship events. Although he took up a new post in the Faculty of Medicine in 2018, he remains an adjunct professor in the School.

A key part of BodyWorks was the Changing Aging program that had been pioneered by Sonya Lumholst Smith in the 1990s and acquired by the school in 2004 from the Department of Athletics and Recreation. The new manager, Suzanne Jolly, reported to Wendy Frisby in her role as associate director of student and community engagement and to Shannon Bredin, Gail Wilson and Barry Legh who provided program oversight. The school also supported hiring a staff member to expand international undergraduate student enrolments and coordinate international affairs. The position was capably filled in 2013 by Carlos Cantu who began to oversee the school’s international summer program and contributes to international student recruitment as well as relationship building with peer overseas universities. These were important new staff positions, however, during this same time the school struggled to identify cognate areas for hiring faculty members that would be supported by everyone. Ultimately, a major breakthrough was reached at a retreat led by Mark Carpenter, Brian Wilson and Nikki Hodges, when the group agreed to a mixed approach – to hire a research faculty member in socio-cultural studies, a teaching faculty member in the area of statistics and a lecturer in a jointly funded exercise nutrition position with the Department of Athletics and Recreation.

A fortuitous opportunity subsequently arose when UBC Provost David Farrar, approached Sparks in the fall of 2014 about the potential for a fully funded spousal appointment for exercise psychology specialist Guy Faulkner, the husband of newly hired Associate Vice-President Equity and Inclusion, Sara-Jane Finlay. The school eagerly supported the proposal, enabling the appointment of Faulkner, who also had the distinction of holding a CIHR Chair in Applied Public Health. John Kramer’s research interests are focused on understanding the relationships between spinal cord injuries and neuropathic pain. Like ICORD colleague Chris West, he is a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and a Rick Hansen Institute Scholar. His research program is playing a critical role to develop neuro-imaging and quantitative sensory testing techniques to better understand how changes in the central nervous system relate to the development of neuropathic pain, and to explore the relationship between pain, neurological recovery, and other secondary health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease.

Andrea Bundon joined the faculty in 2016 after completing her PhD at UBC and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Peter Harrison Centre for Disability Sport at Loughborough University (United Kingdom). Her research uses community-based methodologies to explore the experiences of people with disabilities in sport and exercise environments including the Paralympic Movement. She has also published extensively on the use of digital tools and technologies in qualitative research. Eli Puterman was appointed to the faculty of the school in 2015 as a Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Health. A Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar, his research seeks to understand the interplay among stress, aging, and exercise, and how physical activity can mitigate the biological and psychological antecedents of disease. As director of the Fitness, Aging and Stress (FAST) Laboratory, his team is developing new intervention trials and laboratory-based studies to assess the extent to which both acute and long-term exercise can strengthen psychological and biological stress responses and immune function in children and adults.

After completing her PhD in the school in 2015, Carolyn McEwen was appointed as a teaching faculty member who could anchor the area of statistics in support of both undergraduate and graduate students and teach courses in research methods, statistics, and sport and exercise psychology. She made immediate strides towards creating connections between course content and students’ personal experiences and future goals to develop understanding of the application of acquired knowledge. Her unique and dedicated approach to curriculum design effectively challenges students to develop information and research literacy skills, while exploring quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches to research in kinesiology.

Following endorsement of the shared funding strategy with the Department of Athletics and Recreation, a joint search was conducted that resulted in the 2015 appointment of Emma McCrudden to a position evenly divided between the school as lecturer, sport and exercise nutrition, and the Department of Athletics as sport dietician.

In addition to successfully filling these planned appointments, the school was able to take advantage of other strategically significant opportunities to further sharpen its focus in areas of human wellness. In January 2014, Sparks was approached by the director of ICORD (International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries), Wolfram Tetzlaff, about the school serving as ‘home department’ for applicants for the Rick Hansen Institute/ Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award program. If successful, the applicants would receive five years of salary and an office and lab at ICORD, along with start-up funds to support their research. Ultimately, the school supported three applicants and two were successful, enabling the appointment of exercise physiology specialists Christopher West and John Kramer as assistant professors.

In addition, the school was able to renew the CRC Chair position that Mark Carpenter had held for its two terms. Carpenter was appointed full time in the school, and a search was conducted to fill the vacant chair. In June 2014, the school nominated Eli Puterman for the position, pending the success of his CRC application in Ottawa. The application was subsequently approved in Ottawa, and Puterman was named assistant professor, Canada Research Chair Tier 2, Physical Activity and Health. The next appointment was that of school graduate alumna Andrea Bundon as assistant professor in socio-cultural studies in health, physical activity and sport.

Finally, the school supported hiring a teaching faculty member at the Instructor level who could anchor the area of statistics and work with undergraduate and graduate students. After a rigorous search, the school was able to hire Carolyn McEwen. A PhD student in the school at the time, McEwen’s hiring date was set to January 1, 2016, making hers the final faculty appointment of Bob Sparks’ tenure as director.Photo caption for Bundon: Dr. Andrea Bundon joined the faculty in 2016 after completing her PhD at UBC and a postdoctoral fellowship in psycho-social health and wellbeing at the Peter Harrison Centre for Disability Sport at England’s Loughborough University. Her research, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, uses digital storytelling to explore the impacts of the para-sport programs created as part of the legacy of the London Paralympic Games on the physical activity experiences of young people with disabilities.

Continuing the Journey

On the evening of November 13, 2015 in the newly constructed Robert H. Lee Alumni Centre, a large crowd applauded long and enthusiastically as Martha Piper walked to an awaiting speaker’s podium. Back at UBC to serve as interim president during a 10-month search that culminated in the appointment of Professor Santa J. Ono as UBC’s 15th president and vice chancellor, Piper thanked alumni and donors in attendance for their support of the largest university capital campaign ever completed in Canadian history. Launched in 2011 under the presidency of Stephen Toope, the start an evolution campaign exceeded its goal of $1.5 billion with a final total of $1.624 billion. The capacity crowd listened appreciatively to Piper’s familiar and assuring voice, and those of faculty members and graduates who spoke in similarly grateful terms about their campaign-supported endeavours, and then erupted even more eagerly when the campaign’s final tally was officially announced.

The celebration on that evening symbolized invigoration on the part of the entire UBC community as the campaign’s success enabled a vast spectrum of unprecedented opportunity. Fittingly, the revelry in the Robert H. Lee Alumni Centre took place on an evening that was almost exactly a century after UBC had welcomed its first students in 1915. Now among the world’s top-ranked research institutions with a combined total of some 50,000 students on two thriving campuses, the people of UBC had a great deal to celebrate during the auspicious 2015-16 academic year. Conspicuously absent, however, was Stephen Toope, who had been the chief architect of the campaign but had left UBC as the campaign wound down, ultimately to take up a new post as vice chancellor of the University of Cambridge. The news of his appointment to Cambridge after leaving UBC exclaimed a decidedly compelling footnote to the hundred-year story of the University’s altogether extraordinary evolution.

Although not a direct beneficiary of the campaign’s success, there was little doubt that the School of Kinesiology, with its unique commitment to the biological, behavioural, and sociocultural study of physical activity, sport, and health, was well positioned to make its own rich contributions to humankind. The school’s undergraduate degree programs were now among the most sought-after at UBC among entering students from across Canada and many points in the world, who viewed the BKin degree as an appropriate foundation for an increasingly wide range of professional programs, including medicine, and as an appealing alternative to the faculties of arts and of science as a platform for a modern liberal education. Equally importantly, its research capacity was growing by leaps and bounds, and UBC president Stephen Toope is pictured with Clara Hughes at a 2008 Congregation ceremony in which an honorary degree was conferred upon Hughes in recognition of her extraordinary achievements in both summer and winter Olympic games. As UBC president and vice-chancellor from 2006 to 2014, Toope made numerous leadership contributions to UBC, highlighted by the Start an Evolution capital campaign that raised over $1.6 billion and helped to further elevate UBC’s reputation among the world’s most revered institutions.

Student receiving award, Gail Wilson and Bob Sparks (Bob Sparks to provide details on this picture - ie Gail’s role in recognizing outstanding students? ID the student in the picture and the occasion and year in which it was shot (2011 I think). In her role as undergraduate program coordinator, Gail tirelessly advocated on behalf of the school’s undergraduate students and each year helped students identify and apply for awards and scholarships in the university, faculty and school.

some 7,000 graduates were now engaged in the broad fields of human movement science, physical activity and health across the nation and beyond.

In this regard, the school’s evolving expertise and collaborative approach to exploring new frontiers in health promotion, disease prevention and treatment were aligned with the university’s own vision statement that had remained unchanged since it had been introduced 18 years earlier – “to serve the people of British Columbia, Canada and the world.”

In the final two years of his tenure as director, Bob Sparks made certain that no stone was left unturned to ensure that the school had done all it could in support of the spirit and objectives of Place and Promise, work that capped off a remarkably eclectic career. In addition to his work within the school, he had served for three terms on the University Senate and participated in various Senate committees and other groups in pursuit of enhancing the university’s learning and research environments as well as its service to alumni and the wider community. As chair of the Senate Academic Building Needs Committee he helped raise the profile of facility issues at the Point Grey campus, and spearheaded an action plan to involve the faculties and Senate more directly in campus planning and development. In his capacity as chair of the Senate Admissions Committee, he worked closely with the faculties and administration to monitor and update admissions policies and support the university’s strategic priorities in admissions innovation, campus diversity, Aboriginal engagement and international engagement. He actively supported the Senate Ad Hoc Committee on Student Mental Health and Wellbeing and contributed to a related Senate review that resulted in increased awareness and responsiveness by Senate committees. In his capacity as director, he ensured the school had its own strategies in each of these areas and was engaged with the university’s core strategic initiatives including a new central administration focus on health.

During the final year of his tenure as director, a search committee identified and recruited his replacement in the person of Robert Boushel, a Canadian-born and internationally recognized scholar. After receiving his PhD in anatomy and physiology from Boston University, Boushel’s 20-year teaching and research career began at Concordia University in his home town of Montreal, followed by his appointment within the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, where his work was focused upon broad areas of exercise physiology. Prior to assuming his role as the school’s seventh director, he served as professor and chair in physiology of the prestigious Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences (formerly Stockholm University College of Physical After an extensive international search, Robert Boushel was appointed as director of the UBC School of Kinesiology on June 1, 2015. A Canadian-born and internationally recognized scholar, Boushel received his PhD in anatomy and physiology from Boston University and subsequently began a 20-year teaching and research career at Concordia University followed by his appointment within the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, where his work was focused upon broad areas of exercise physiology. Prior to assuming his role as the school’s seventh director, he served as professor and chair in physiology of the prestigious Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences.

Education and Sports), the oldest institution in the world in its field, founded in 1813 by gymnastics pioneer Pehr Henrik Ling. Sparks heartily applauded the appointment of Boushel as “an absolutely superb choice,” and spoke with noticeable enthusiasm at a reception held in War Memorial Gymnasium in June of 2015 to officially welcome his successor. Just over two years later as he prepared to officially retire, Bob Sparks reflected on the period in which he served as director, and of his determination to emphasize collegial and distributed leadership that had indeed borne fruit.

“Clearly during my directorship there were people who worked hard to lead the School, yet everyone contributed their part through research, teaching and community engagement. At the end of the day, when I looked at all this, I found that every single individual in the School had stepped up and played an important leadership role in making the School what it is today. The growth and development of the School in recent years should not be understood as my success, but as the success of the group in pulling together and raising the bar of our collective accomplishments. There is great mutual support, enthusiasm and esprit de corps in the School. I am really proud to have been part of that story.”