18 minute read

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER 3

The Early Years

IN ADDITION TO RECRUITING FACULTY, ONE OF BOB OSBORNE’S MOST IMPORTANT TASKS IN OVERSEEING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION WAS THE ACQUISITION OF APPROPRIATE SPACE IN WHICH THE PROGRAM

COULD GROW, AND NO PRIORITY WAS OF GREATER IMPORTANCE IN THAT REGARD THAN ESTABLISHING A MODERN GYMNASIUM. FORTUNATELY, SUCH AN UNDERTAKING ALIGNED WELL WITH A DESIRE ON THE PART OF THE ALMA MATER SOCIETY AND THE UNIVERSITY TO BUILD A WAR MEMORIAL FOR THE 247 STUDENTS LOST IN THE TWO WORLD WARS.

UBC’s war dead included Physical Education graduate, James Douglas Hamilton. After serving as a navy patrolman in the North Atlantic during World War II, Hamilton enrolled in the UBC Canadian Officer Training Corps while studying for his Physical Education degree, and returned to action as a lieutenant in the battle for the Korean Peninsula. After learning that he had been killed in action, his friends and classmates established an undergraduate bursary, the Lieutenant James Douglas Hamilton Prize, in his memory.

With students and alumni driving the fundraising campaign to build War Memorial Gymnasium, Osborne focused upon working with the Alma Mater Society and the university to ensure the proposed building’s finer details could meet the needs of the program and other university purposes. These included its use as an exam hall, a venue for convocation ceremonies and the annual campus Remembrance Day services, which were held in the entry foyer where names of fallen student soldiers were enshrined on bronze wall plaques.

In a fitting coincidence, the architect selected to design the new gymnasium was former UBC oarsman and 1932 Olympic medalist, Charles Edward (Ned) Pratt. After graduating from the School of Architecture at the University of Toronto in 1946, Pratt returned to Vancouver and joined the architecture firm of Sharp and Thompson, which had done the planning and design work for the UBC campus in 1913 along with four of its original buildings. At a cost of $750,000, the 3,000-seat War Memorial Gym took 17 months to build and was officially opened on February 23, 1951 with Jack Pomfret coaching the Thunderbirds in a basketball game against Eastern Washington, followed by a student “sock hop.”

It was, at the time, the largest gymnasium at any Canadian university, comprised of the main gymnasium with a sprung maple floor, a smaller gym in its basement for boxing, wrestl-ing and tumbling, six bowling alleys, a cafeteria, a steam room, and a physiotherapy room. It also housed the new headquarters of the Department of Physical Education, which consisted of an office for Osborne and another large room with an assortment of desks for a growing roster of teaching staff. The imposing edifice also stood as a compelling symbol of the university’s bred-in-the bone sport culture and its commitment to excellence in physical education, however, with its use almost exclusively restricted to male teams and students, it also reflected prevailing attitudes concerning gender and sport.

In 1952 Senate approved the reorganization of the department as the School of Physical Education, and the program assumed greater autonomy over its operations and planning. By this time, the curricula for all four years had been more or less solidified after a certain amount of trial and error in the program’s formative stages. Maintaining its primary focus on training physical educators, the school required its students to complete a predetermined series of activity courses that covered rules of play and basic skills across a broad spectrum of team and individual sports. Individual courses were also required in sport history and sport administration, both taught by Bob Osborne. In addition, physical education students

were required to take an equal number of courses from other departments within the Faculty of Arts and Science, including junior level graduation prerequisites.

“There was no customization in physical education; everybody had to take the same thing,” recalled 1950 graduate Carol Slight. “You also needed four courses a year from arts and science, so obtaining a degree in physical education essentially meant taking a double major.”

Physical education students also continued to assist faculty members to teach junior level activity courses that were now compulsory for all UBC students. The practical experience continued to be valuable for the majority who would enter teacher training the year after receiving their bachelor of physical education degrees. As demand for the compulsory classes continued to rise in step with general student population growth, new faculty members were added, beginning in the fall of 1948 with the appointment of an accomplished Canadian golfer and tennis player named Marjorie Leeming. A one-time competitor in the US Open in tennis, Leeming came to UBC after many years of teaching and administrative service in Vancouver schools, but resigned her teaching post just three years later to accept a job as assistant to UBC Dean of Women, Dr. Dorothy Mawdsley.

Other early newcomers to the women’s program included Hawaiian-born dance specialist Marjorie Miller and gymnastics Left: Game day for the UBC varsity XV against an Oxford-Cambridge combined side in 1955.

Left to right: BC Rugby Union president Bob Spray, UBC coach Albert Laithwaite, men’s athletic director Bus Phillips and Oxford coach Peter Kininmonth.

Below: Bob Osborne and Canadian Governor General Vincent Massey inspect War Memorial Gym on opening day, February 24, 1951.

Left: 1949 graduate and faculty member Dick Penn was the manager of the varsity basketball team and coach of the junior varsity team. He married Marjorie Miller, a dance specialist who also taught in the Department of Physical Education in its early years. They had four children together, including son Gordon, who was a 1978 BPE graduate and an all-star running back with the Thunderbirds football team.

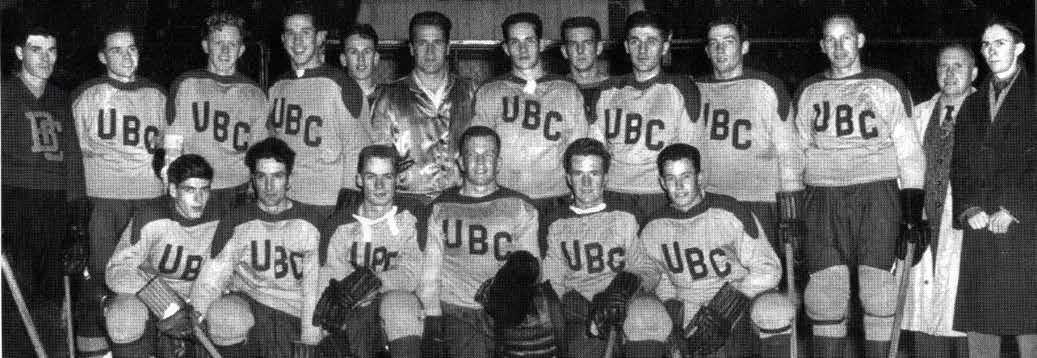

Below: The fortunes of the Thunderbirds hockey team soared in 1950, led by physical education students Terry Nelford and Clare Drake, when the Thunderbirds won defeated the 1949 US champion Colorado College in a best-ofthree series and then won the western Canada championships against the heavily favoured Alberta Golden Bears, coached by Maury Van Vliet. Drake went on to an extraordinary coaching career at Alberta and induction into Canada’s Hockey Hall of Fame. Marjorie Leeming, an accomplished golfer and tennis player, was appointed to the faculty in 1948. A one-time competitor in the US Open in tennis, Leeming came to UBC after many years of teaching and administrative service in Vancouver schools. Helen Eckert taught women’s basketball and archery and was the coach of UBC’s first women’s varsity volleyball team. While at UBC, Eckert undertook a scientific examination of competitive basketball among women, which resulted in the elimination of the ill-conceived “girls rules” of basketball at UBC and elsewhere.

Frank Gnup attracted a stream of outstanding student-athletes to both the Thunderbirds football and baseball teams. Gnup’s football teams struggled against their more experienced and better-funded American opponents in the US Evergreen Conference. In his first three seasons, the Thunderbirds posted a record of 6-17, prompting the team’s withdrawal from American intercollegiate play to join the newly formed Western Canada Intercollegiate Athletic Association. Gnup’s team won the inaugural conference championship in 1959 and qualified for UBC’s first-ever national championship appearance.

teacher Helen Bryan, a native of northwestern Ontario and physical education graduate of McGill, where she had been a classmate of May Brown. Subsequent hires on the women’s side were 1952 UBC graduate Diane Bancroft, another dance specialist who attended graduate school at the prestigious Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Helen Eckert, who taught women’s basketball and archery and later became the coach of UBC’s first women’s varsity volleyball team. While at UBC, Eckert undertook a scientific examination of competitive basketball among women. After concluding that no ill-effects were in evidence among girls and women who played competitively, the so-called “girls’ rules” of basketball were discontinued at UBC and elsewhere.

Newcomers on the men’s side included recent graduates Reid Mitchell and Dick Penn, the latter of whom coached junior varsity basketball and headed up the growing intramural sports program. Shortly after his appointment, Penn married Marjorie Miller. They subsequently raised four children, one of whom was physical education graduate Gordon Penn, an all-star football player and scoring leader with the Thunderbirds in the mid-1970s. In addition to hiring teaching staff, Osborne appointed former Pro-Rec instructor, R.J. “Bus” Phillips, as men’s athletic director in 1953, thanks in part to the work of physical education student Brock Ostrom, whose lobbying efforts resulted in the Alma Mater Society implementing an annual student fee of $3.25 to pay for enhancements to the men’s varsity program. Phillips’ appointment relieved Osborne of the task of overseeing the administrative demands of the varsity teams, which in the case of the men’s teams included an increasing amount of travel for intercollegiate play and recruitment of highly specialized coaches. With Osborne’s support, Phillips successfully convinced university administration to provide direct funding to complement the athletic fees paid by students. Now with sufficient funds to pursue top-flight coaches, Phillips and the omnipresent Gordon Shrum wasted no time in hiring Seattle native and University of Washington graduate, Don Coryell, as football coach. Coryell stayed just two seasons before returning to the USA where he achieved storied success at both the college and pro levels, winning more than 100 games each with San Diego State University and the San Diego Chargers, and earning a place in the NFL Hall of Fame.

Coryell’s successor was Frank Gnup, a graduate of New York’s Manhattan College. Gnup came to UBC in 1955 at the invitation of Shrum, who had approached him in Hamilton during Gnup’s time as a player with the Hamilton Tiger Cats. Renowned at UBC for his football savvy and magnanimous personality, Gnup attracted a stream of outstanding studentathletes to both the Thunderbirds football and baseball teams. He also enlisted the help of a recent physical education graduate and newly appointed faculty member named Bob Hindmarch as assistant football coach. As was the case with UBC teams under Coryell, however, Gnup’s charges struggled against their more experienced and better-funded American opponents in the US Evergreen Conference. In his first three seasons, the Thunderbirds posted a record of 6-17, prompting Phillips and Osborne to withdraw from American intercollegiate play to become full members of the newly formed Western Canada

Albert Laithwaite’s 1951 varsity rugby team, pictured celebrating its McKechnie Cup victory that year, is regarded as one of the finest in UBC history.

Peter Mullins, a 29 year-old Australian decathlete and 1948 Olympian, was appointed in 1955 to teach and coach track and field. Mullins had previously received a track scholarship to Washington State University where he lettered in both track and basketball and earned a Master’s degree. He received a doctorate from Washington State in 1961.

Intercollegiate Athletic Association (WCIAA). Gnup’s team met with great success in the first year in the new league, winning the conference championship in 1959 and qualifying for UBC’s first-ever national championship appearance.

In the same year that Gnup arrived at UBC, Phillips also hired a 29 year-old Australian decathlete and 1948 Olympian named Peter Mullins to teach and coach track and field. Mullins had received his Diploma of Physical Education at Sydney Teachers College in Australia, and subsequently received a track scholarship to Washington State University where he lettered in both track and basketball and earned a master’s degree. He received a doctorate from Washington State in 1961, making him the second Australian physical education faculty member to do so after his countryman Max Howell, who had been appointed to UBC’s faculty in 1954 after completing doctoral studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Athletic talent was abundant among UBC students in the 1950s, particularly within sports that underscored Vancouver’s enduring British foundations. Rowing had long been popular in the city thanks to the presence of the Vancouver Rowing Club, After assisting Osborbe to set up the department, Douglas Whittle became the first faculty member appointed on the men’s side, and was assigned duties which included teaching swimming and gymnastics, coaching the men’s swimming and junior varsity basketball teams and a variety of administrative duties.

whose members included an accomplished oarsman named Frank Read. After an injury ended his career, Read entered the hotel business, but returned to the sport as a coach of the VRC/ UBC oarsmen owing to a cooperative partnership brokered in 1949 between Osborne and the rowing club’s directors. His intensive training program soon produced results, exemplified by VRC/UBC crews competing against top Canadian teams, including the Toronto Argonauts, whose eight-man crew defeated Read’s students for the right to represent Canada at the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games.

Rugby teams also enjoyed tremendous success under the coaching of Albert Laithwaite, and later Max Howell, who first came to Vancouver in 1948 as a 19-year-old member of the Australian national team. On numerous occasions the UBC Varsity XV won the coveted McKechnie Cup provincial championship, thanks to a seemingly endless list of outstanding players, including physical education students Marshal Smith, Ted Hunt, Don Shore and a former British military policeman named Bob Morford. The Thunderbirds soccer team was similarly dominant in the Lower Mainland league, and

Marshal Smith

Marshal Smith was one of Albert Laithwaite’s top rugby players between 1947 and 1951. A member of the School’s second graduating class in 1950, he married classmate Patricia McIntosh, a gifted basketball player for the Vancouver Eilers and a member of Canada’s 1955 Pan American Games team. Unlike the bulk of his classmates, Smith did not pursue a teaching career but rather followed a series of escalating leadership positions in the emerging field of municipal parks and recreation. Energetic and practically minded, Smith earned the respect of his peers and elected members of Vancouver’s Board of Parks and Recreation, particularly during the early stages of his career when he led the design and construction of the city’s popular Kitsilano and Kerrisdale Community Centres. He was eventually named the first-ever director of recreation for the Board of Parks and Recreation and was a co-founder of the BC Recreation Association, a professional organization that included a growing number of UBC graduates. He also left his marks upon the School of Physical Education as a member of the committee that in 1958 proposed and recommended a new degree program in recreation education.

Left: 1948 UBC men’s swim team at Crystal Pool on downtown Vancouver’s Beach Avenue.

Middle: UBC Eight crosses the finish line in a gold medal finish in the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

Top, right: The 1956 Varsity Four were first UBC athletes to win Olympic gold medals, in 1956 in Melbourne. The crew included physical education student and future faculty member Don Arnold (far right).

as a result moved up to the highly competitive Pacific Coast League in 1951. The team’s top player in the late forties was, by all accounts, Jack Cowan, who became the first UBC player to play for a European professional side when he signed with Scotland’s Dundee United in 1949. Following Cowan’s departure, physical education student Bill Popowich became UBC’s most prolific scorer, netting 12 of UBC’s 30 goals in their inaugural season in the Pacific Coast League.

Not surprisingly, the news that Vancouver had been chosen as the site of the 1954 British Empire Games was greeted with great enthusiasm on Point Grey, particularly when Osborne announced that an international-sized pool and diving platform would be constructed as a competition venue next to War Memorial Gym. The fortunes of the swim team improved immeasurably as a result of the new pool on campus, building on a solid foundation established by Doug Whittle, who until this time had coached UBC’s men’s swim team and taught swimming and lifesaving classes at Crystal Pool in downtown Vancouver.

The most glorious moment of the Games for UBC did not occur in the pool, however, but on a rowing course set on the Vedder Canal near the Fraser Valley town of Chilliwack. As the Duke of Windsor and a few thousand spectators looked on, an eight-man crew of UBC students that had trained under Frank Read defeated the heavily favoured British crew to win gold medals. At the invitation of a noticeably impressed Prince Philip, the British Empire Games champions went to England the following summer to compete in the prestigious Henley Royal Regatta, where they finished second to the USA after defeating the defending world champion Soviets. UBC rowers continued to train under Read thanks to the ongoing partnership with the Vancouver Rowing Club, one that paid off once again at the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games where a four-man crew that included physical education student and future faculty member Don Arnold won the university’s first Olympic gold medal. Later that same day, physical education student Wayne Pretty was part of Canada’s eight-man crew that claimed silver medals in a tight race with a powerful American boat from Yale University. The success of

the UBC crews in Melbourne further entrenched Vancouver, and UBC, as training centres for aspiring competitive rowers who would represent Canada at future Olympic Games, including medal-winning performances for UBC students in 1960 in Rome and 1964 in Tokyo.

Melbourne also proved to be a showcase for UBC’s other international-calibre competitors. With Jack Pomfret serving as an assistant coach, basketball players Ron Bisset, John McLeod and Ed Wild competed for Canada in the Melbourne Games, as did track athletes Doug Kyle and a young medicine student named Doug Clement, who in later years would play an important role in establishing a sport medicine clinic at UBC in partnership with the School of Physical Education. Overall, the appearance and triumph of so many UBC students in Melbourne sent a clear signal to all of Canada that UBC and its varsity athletic program had become a destination for many of the nation’s finest student-athletes, including those who aspired to compete against the world’s best.

Frank Read

Under rowing coaching Frank Read, the success of VRC/ UBC rowing crews at the 1954 British Empire Games and in the 1956 Olympic Games further entrenched Vancouver and UBC as training centres for aspiring rowers who would represent Canada in future Olympic Games, including medal winning performances in 1960 in Rome and 1964 in Tokyo.

It would take some years, however, before UBC’s female students enjoyed the same opportunities in competitive sport as their male counterparts. Although intercollegiate sport was well entrenched on Point Grey, it continued to exclude women’s competition. The noticeably skilled and well-coached “Thunderettes” women’s basketball team, by way of example, continued to play in the Lower Mainland’s senior leagues, with their schedules augmented only slightly by friendly intercollegiate matches with Western Washington University, Whitworth and Everett colleges, or by the occasional train trip to the University of Alberta or the University of Saskatchewan. UBC’s women’s field hockey teams also enjoyed tremendous success in local competition. Under the coaching of May Brown, UBC enjoyed consistent success in the highly competitive Greater Vancouver Senior Women’s Grass Hockey League, and was even more dominant against American teams, rarely losing a game in 10 consecutive tournament victories at the Northwest Collegiate Championships in Seattle.

One of May Brown’s field hockey standouts during this period was 1952 physical education graduate Barbara “Bim” Schrodt. Inspired by Brown’s passion and expertise as a physical educator, Schrodt attended graduate school at the University of Oregon where she earned a master’s degree in 1957. In the meantime, however, her former coach and mentor left UBC in 1955 and was temporarily replaced by a former McGill classmate named Alice Trevis. Trevis’ decision to return to Montreal after just two years at UBC opened the door for Barbara Schrodt to return to her alma mater as a teacher, field hockey coach and the university’s first women’s athletic director.

Schrodt’s return to Point Grey and her influence upon women’s athletics was just one element of the evolutionary period that took hold within the school in the later part of the 1950s. Another was the closure of the Vancouver Normal School in 1956, which resulted in the Department of Education at UBC expanding to offer full degree programs, including undergraduate courses in physical education. With demand for physical education instruction at UBC now at an all-time high, teachers from the Vancouver Normal School received joint appointments in the School of Physical Education and Department of Education. A third element was the expansion of public municipal recreation facilities and services in urban regions throughout the province, and an emergent need for the training of sport and recreation administrators that the UBC School of Physical Education was uniquely positioned to provide.

Finally, amid of so much change both on the campus and in communities throughout the province, discussions about UBC becoming home to Canada’s first graduate program in physical education pointed to an even more promising destiny.

Left: Marilyn Peterson (bottom row, far left) led the

Thunderettes to UBC’s first-ever Western Canadian Women’s Basketball Championship in 1960. Peterson was also active in student affairs and together with fellow student Bob Schutz drafted proposals for curriculum reform. After completing her masters degree at the University of Oregon, 1951 BPE graduate Barbara Schrodt (top row, far right) returned to UBC as a faculty member and women’s grass hockey coach.