MAGALOGUE 5

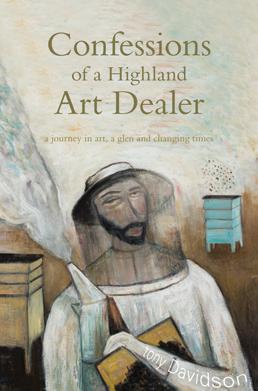

COVER IMAGE

Ten Birds

Patricia Paolozzi Cain

coloured pencil | 74cm x 61cm

+44 (0) 1463 783 230

art@kilmorackgallery.co.uk

Kilmorack Gallery, inverness-shire iv4 7al SCOTLAND

Contents Magalogue 5 5 Playful Exploration 8 The limitless sculpture of illona Morrice by Tony Davidson Lotte’s Creatures 12 Dreams and Works of Lotte Glob by Tony Davidson Point of Departure 16 Pilgrim 18 Looking at a Painting by Georgina Coburn Three Questions to Patricia Paolozzi Cain 22 One Train, Two Men and Three Trees 24 from the vaults 26

4

Magalogue 5

The difference between art and craft is that artists always seeks an answer, while crafts people believe they already have it. They know how it should be done and follow this tradition. There’s nothing wrong with this. Icons and Buddhas are wonderful, but, maybe, when the world needs to find answers and new ways to live, it needs its artists more than ever.

In this Magalogue we explore childlike fascinations. Patricia Cain answers questions on her complex weblike paintings, we have the essay from Lotte Glob’s children’s book and consider illona Morrice’s diverse and brilliant portfolio.

Tony Davidson Director of Kilmorack Gallery

Earth

Sisters ii | ANTOHNY SCULLION

Strata Jar | PATRICIA SHONE

Whelped | ROBERT POWELL

Strata Jar | PATRICIA SHONE

Whelped | ROBERT POWELL

Stack (Lost Rock) | PETER DAVIS

Stack (Lost Rock) | PETER DAVIS

Landscape i | PETER WHTE

Sweet Pea 6 | LIZZIE ROSE

Playful Exploration

The limitless sculpture of illona Morrice

by Tony Davidson

by Tony Davidson

8

Arrow Head ceramic | 54cm (h) x 20cm x 15cm

I am reminded of a child’s wonder. She explores a rockpool where there could be a sea urchin or a crab, and she picks up a tiny shell. Who lived there, she whispers? What if it were as big as me? Over there is a bird. It is weird and beautiful with its long beak. She knows there have always been people living here. They had stone axes and arrowheads, helmets and long Viking faces. Elsewhere, in the far north, there were Inuits with round faces. Look at this seed in my hand. It is perfect, with a life-giving opening, and look up to the moon. How it shines. Could I touch it if I had long, long arms? Illona Morrice is now no longer a girl. There are five decades of experience in every new sculpture, with fifty years of technical knowledge, as well as other fruits of a full-lived life in each piece, but the feeling of seeing with young eyes remains. Illona Morrice’s sculpture pulls you away from the mundane and up into the living realm. Maybe that’s why she does it, as a lifeline to life.

Illona Morrice’s fearlessness in tackling new ways of working is unique. Her original medium was clay, beginning her ceramic journey as a girl in Copenhagen. Fifty years on and she has developed a way of modelling that allows her to work on a large scale without shrinkage and cracks as the piece fires in the kiln. In a clay sculpture, lines are relatively soft and organic, so if she wants a sharp shinny finish, illona will turn to bronze, but bronze itself has a hard lifeless feel, so illona plays with its strengths, making shapes that clay won’t hold, knowing that her creation can survive for millennia with only the darkening of its patination.

9

Illona carves stone too, and this medium brings another dimension to her work. Ceramics are formed from clay and fire, but marble and soapstone have a metamorphic past, and this squashed rock-chronicle gives an individual beauty and history into each stone piece. It also creates fresh challenges because every stone dictates what it can become and working with it is a collaboration. With its permission, illona, among other things, has made a giant nose (at the same time she had nose cancer,) a pair of rams and pebbles at the beach.

I’ve known illona’s work for thirty years. First when I was helped her cast direct-wax sculptures of ladies on bicycles in a foundry in a pre-gallery life. Her work was different again back then, reflecting another stage of her life, but her need for exploration was there, driving the creative act. Making great art should never be easy and repetitive and repetitive, with results that are predictable and safe. It needs to delve into every existential existence and find new ways to express what it is like.

I am reminded of a child’s wonder. She stacks pebbles making a tower and then draws pictures of her family and the world around her: trees, people and the sea. Each drawing is different, better, a challenge and soon the room is full of paper. This is the artistic act. It is an urge that we all once felt but most have lost. ‘Every child is an artist,’ Picasso said, ‘The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.’ I love children’s art, but a mature artist can bring more.There’s a life-lived in each piece by a grownup artist, and years of practice are not always wasted. As an

10

adult, dreams can become solid things. They make the world around us. If you stop learning on the journey, what is in front of you loses its magic, and Illona Morrice has never stopped. What will she do next? What will you do next? It’s always best to answer this question with fearlessness and see what’s out there.

11 7

Henchman andYarl ceramic | 70cm high

Lotte’s Creatures

Dreams and Works of Lotte Glob

by Tony Davidson

A selection of Eribol Creatures LOTTE GLOB

12

If you think you know everything out there, you’re wrong. There’s always more. Unknown things hide in cracks or come out only at night when nobody is there to see them. Creatures exist that are joined to our world, but only just. They connect to us by a thin night-thread, and can be glimpsed sometimes, but only if you look beyond what most see. This special vision is the gift of children and artists, and what many don’t realise is that most things glimpsed from the corner of your eye are very pleasant: a singing creature or a six-legged wanderer. It is often what is right in front of you that is not so nice.

Lotte has told me that she is an insomniac, and at night she lies excitedly thinking of Loch Eribol, which is down-croft from her unslept in sleeping place. As the day before and the day-to-come races before her, she thinks about the extraordinary creatures she shares the croft with. They live under the surface of the water. There is a whole civilisation, she tells me, with a large bridge, and they have always been there, happily singing, stargazing and exploring, doing what creatures do. Things fall from the sky - space junk and meteors, she tells me. I often see a face or a body in a tree, and, not far from home, there is a Green Man who stares from a rockface in a grotto they call the Fairy glen. This way of looking at the world has been with us far longer than our present digital obsessions, or the fairly recent scraping of the planet by giant mechanical machines. Nature’s underbelly should be there to nurture us. Seeing its infinite ecology connects us with… with everything, below and above the loch and

13 9

within ourselves.

The creatures in this book are leaving. They’ve had enough of the dredging of the loch’s bottom, pollution from fish farms and the plastics which now lie around and within its kelpy water. Our friends see that there is nothing left to do but abandon their below-water lives and look for a new home. This is just one very deep loch in the north of Scotland. How many creatures are leaving other places – the Antarctic, the Amazon, and the tarmacked nature right next to you? It is a sad thought for people who see from the corner of their eyes, and where will our creatures go?

Lotte Glob was born in 1944 and was an apprentice to Danish ceramic artist Gutte Erikesn at the age of fourteen. She moved from her native Denmark to Ireland when she was nineteen and soon moved to Durness on the northwest corner of the Scottish mainland. In 2001 she took over a croft on Loch Eribol, always maintaining a slight Danish accent and a devotion to playing and creating with clay. An early influence on her work was the CoBrA art movement and in particular Asgar Jorn who encouraged a playfulness and an individualistic freedom. Another influence is the land around her: Ben Hope to the east, the lochans and the peat bogs, and other places few people go.

14

Lotte is known for taking her creations high into the hills and releasing them, so you may see, if you look very very hard, an eternal wanderer looking for a home, peatbog dwellers or a sitting-stone with strange words carved into it. These are gifts back to the world and just like us, they are made from clay, rock and fire.

from Leaving the Loch, a childrens book published to accompany Lotte Glob’s exhibition in Kilmorack, March 2023

15

Loch Eribol Creatues hand-paintined etching | 41cm x 60cm

The Pause Between Waves

Gail Harvey | oil on canvas | 111cm x 170cm

Memorial earth to earth

by Peter White

Almost five years ago, I began a project that involves collecting stones from the hills that I walk in, painting on them and eventually returning them to the top of the specific hills from where they came, as memorials to individuals who have died.

The process started with the idea of walking and making work in memory of people who I have personally known. It has since grown and now I give some of the painted stones to other people. They can name their own dead and keep the stone for a while before giving it back to me, to be returned to the land.

I have also travelled to Palestine on three occasions to continue this project. I gathered stones from specific walks, painted on some of these stones whilst I was there, giving these to people who wished to participate, bringing others back to Scotland to work on. I have now placed some of these stones back into the Palestinian landscape and over the coming years hope to continue to do so.

A memorial stone place in nature and left there. It is painted on a stone from this location and on its back is a name.

18

20

Highland Book Prize 2022 Longlist

Slightly Foxed Biography 2023 Shortlist

‘An unexpected page-turner’

‘It’s just bloody good’

‘A great read. Couldn’t put it down and finished it too quickly. Waiting for the next book now. Buy it.’

21

Three Questions to Patricia Paolozzi Cain

In your latest group of works there’s a strong sense of growth and the architecture of nature. How would you describe the energy in your compositions?

It’s good to be as close to nature as possible, and I think I’m part of the lineage of artists who have become more intimately connected to nature through observation and attention. I’m not making to replicate, but to engage in a process. So the energy in the work is formed through the dynamic process between what I’m observing and making - perhaps documenting my evolving relationship with nature, and this circular process feels like it makes itself. And whilst it’s possible to talk about the subject matter or form of what any particular piece of work ‘is about’ (for example, you’ve mentioned the sense of growth and architecture of nature), for me, my work is more the consequence or evidence of the energy of this evolving dynamic process, and this doesn’t end with the finishing of one particular piece of work.

22

You’ve suggested that the most important question for a maker is what they ‘come to know about the world through making an artwork.’ What has this latest trajectory revealed?

My personal experience of ‘coming to know’ through making work, is that it is both gradual and often physically tied up with the processes I mention above. So coming to know, or becoming aware - which is a matter of consciousness - often happens because as artists, we’re perhaps able to transform our physical experiences of the process. My self-awareness grows because through art, I’m able to realise connections between my own experiences and the world at large. Processes such as letting go or being connected subconsciously manifest themselves in my work. So coming to know depends on developing an internal life of

23

Map i | coloured pencil | 61cm x 81cm

You’ve described ‘nature as a gateway to the internal mind,’ how does this shape the way you work in mixed media?

becoming aware through making work, and I sense that awareness can become apparent through all disciplines, not just art.

My current work has increased my awareness of allowing or enabling myself to become more facilitated without blocking or self-judgement - so you could say that making work is my framework for better locating my authentic self. I could go further in a bigger picture way, by perhaps recognising that the rather devotional aspect of making that I’ve consciously committed to, has a sense of engaging in my larger purpose, and viz. a viz. the world at large, this is how I am meant to contribute.

For me, choices about media, space, colour and scale are closely connected with impressions through senses, and involve sensitivity, attunement, intuition and a kind of think-feel. They are a nuanced and delicate aspect of openness I seek to inhabit.

I think mixed media offers something like a spectrum in the dynamic between known and unknown. Going into the unknown by experimenting with media with which you have little familiarity or mixing media in unfamiliar ways, creates new connections, interruptions, challenges, or interjections which can form chances for expansion. In this sense, mixing media is like a vocabulary from which to chose, and those decisions and choices are also very much part of the dynamic.

24

25

Ten Birds | coloured pencil | 74cm x 61cm

Survival Man

Alan MacDonald oil on board

26

35cm x 30cm

27

28 +44 (0) 1463 783 230 art@kilmorackgallery.co.uk by beauly, inverness-shire iv4 7al

from the vaults

Helen Denerley wolf pack, 1998

30

Strata Jar | PATRICIA SHONE

Whelped | ROBERT POWELL

Strata Jar | PATRICIA SHONE

Whelped | ROBERT POWELL

Stack (Lost Rock) | PETER DAVIS

Stack (Lost Rock) | PETER DAVIS

by Tony Davidson

by Tony Davidson