£3.99

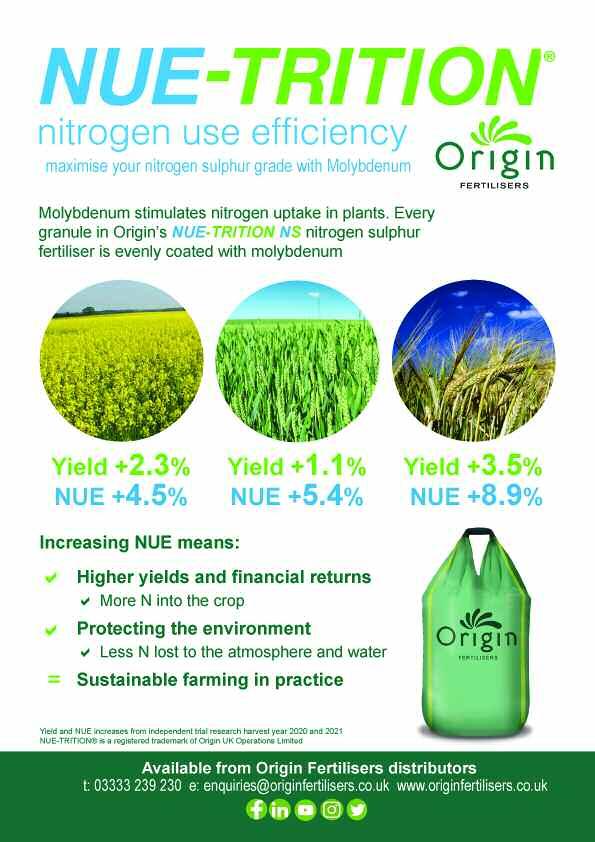

Follow the clues inside to a better NUE...

In this issue...

New Inatreq guidelines page 7

Just how practical are they?

LAMMA lowdown page 79

Pioneering nutrition page 72

An approach from Integrated Soils

CUPGRA Conference page 97

Volume 25 Number 1

February 2023

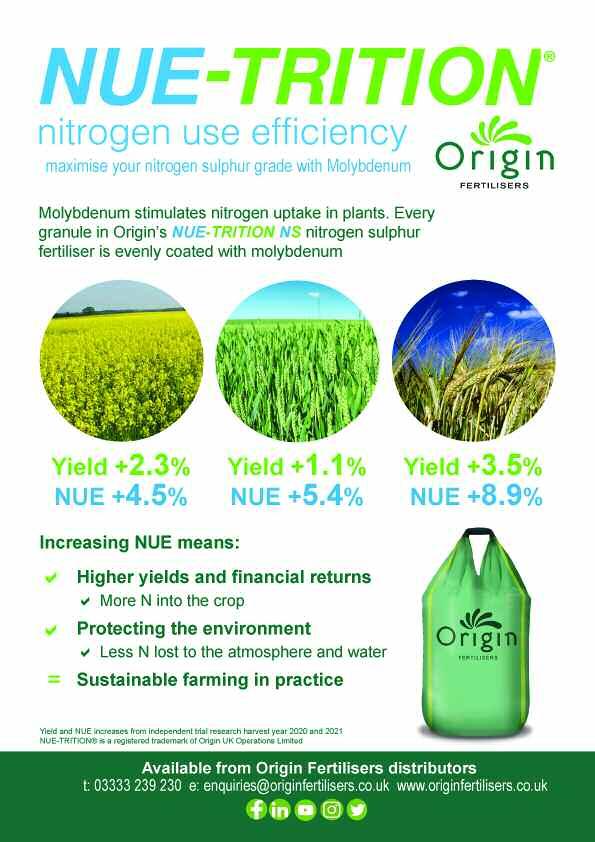

As the spring begins to beckon, thoughts inevitably turn to crop nutrition. With the full impact of the rise in nitrogen prices likely to be felt this season,nitrogen use efficiency comes under a laser focus –– matching crop need to supply and making sure the crop can get hold of it, then use it to build yield,has never been more important for profitability.

invasions, in the vast majority of cases controlling damage falls entirely to cultural methods.

To get this right, it’s important to accurately assess the risk and this is where research funded by AHDB is beginning to reap the rewards (page 29).

Another thorny pest gracing the pages in this issue is cabbage stem flea beetle (page 26).

Editor

Lucy de la Pasture

Sub-editor

Rachael Harper

Writers

Mike Abram

Tom Allen-Stevens

Adam Clarke

Charlotte Cunningham

Melanie Jenkins

Rob Jones

Martin Lines

Lucy de la Pasture

Martin Rickatson

Guy Smith

Richard Styles

Andrew Wilson

Design and production

Brooks Design

Publisher

Steve Kendall

Commercial Director

Angus McKirdy

To claim two crop protection BASIS points, send an email to cpd@basis-reg.co.uk, quoting reference CP/120083/2223/g.

To claim two NRoSO CPD points, please send your name, NRoSO member number, date of birth and postcode to angus@cpm-magazine.co.uk

*the claim ‘best read specialist arable journal’ is based on independent reader research conducted by McCormack Media 2020

Editorial & advertising sales

CPM Ltd, 1 Canonbury, Shrewsbury, Shropshire SY3 7AG

Tel: (01743) 369707 E-mail: angus@cpm-magazine.co.uk

Customer Ser vice Kelsey Media, The Granary, Downs Court, Yalding Hill, Yalding, Kent ME18 6AL, UK

Reader registration hotline 01959 541444

Advertising copy Brooks Design, Tel: (01743) 244403 E-mail: fred@brooksdesign.co.uk

CPM Volume 25 No 1. Editorial, advertising and sales offices are at CPM Ltd, 1 Canonbur y, Shrewsbur y, SY3 7AG England. Tel: (01743) 369707. CPM is published eleven times a year by CPM Ltd and is available free of charge to qualifying far mers and far m managers in the United Kingdom.

Copyright Kelsey Media 2022. All rights reserved. Kelsey Media is a trading name of Kelsey Publishing Ltd. Reproduction in whole or in part is forbidden except with permission in writing from the publishers. The views expressed in the magazine are not necessarily those of the Editor or Publisher Kelsey Publishing Ltd accepts no liability for products and services offered by third parties.

Inside this issue are pages and pages of clues to improving nitrogen, and nutrient, use efficiency –– from soils, to spreaders, discussion on form and function, biologicals, fungicides and the list goes on. All of these play a role in NUE.

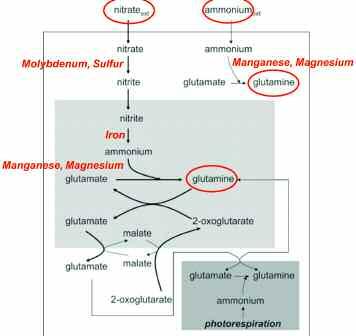

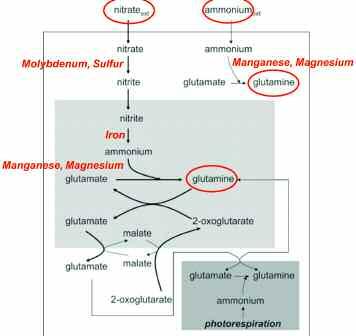

Joel Williams provides real food for thought as he discusses nitrogen as a case study when presenting a model to transition to agroecology at the Hutchinsons’ conference at the end of last year (page 71). He digs into the detail of how different N forms are metabolised and how N can be stabilised –– it’s a quick precis of the detailed course Joel’s running this spring, which several CPM readers have taken advantage of by the look of my Twitter feed!

A more input-focused approach is detailed on pages 50 and 53 –– this would be the substitution phase in Joel’s ESR model. On these pages the role of biologicals and biostimulants is explored as well as taking a tailored approach to crop nutrition so growth is never limited by poor supply.

Late last year Corteva announced new guidelines for the use of its fungicides containing the active, Inatreq. We talk to some growers who had problems after spraying it last spring ––some approached for comment weren’t able to because of an ongoing dispute –– and get some views on just how practical the recommendations are and whether they will be adhered to (page 7).

Theory to Field addresses wheat bulb fly –– a pest that has mostly gone off the radar, unless it’s a problem for you. With no available insecticides left to treat

On-farm assessments, as part of the NIAB-led csfbSMART project, yielded some interesting results last season –– seemingly dismissing the role oilseed rape volunteers could play as a trap crop, an idea previously thought by researchers to be helpful.

Another OSR problem without any plant protection products to aid growers is verticillium.

Innovation Insight (page 20) tracks how a plant breeder found multi-gene resistance to the disease and explores the disease itself, which has only been of importance in the UK within the past two decades.

As the conference season draws to a close, we bring highlights from just a few –– there’s never enough room to properly do these gatherings justice. We bring politics and policy from Oxford Farming Conference (page 37), soil science from AHDB’s Agronomists Conference (page 45) and highlights from the CUPGRA (page 97) –– the go-to conference for potato growers ––as well as how to take those first steps when transforming to an agroecological-based farming system, the main topic at Hutchinsons’ Agroecology Conference (page 70).

New technology in plant breeding is tackling the question of sustainability from a different direction, using gene-editing to enhance crop associations with beneficial soil microbes. We explore this in detail on page 66.

I hope you enjoy reading this February issue of CPM as much as I’ve enjoyed putting it together

Editor’s pick

CPM (Print) ISSN 2753-9040 CPM (Online) ISSN 2753-9059

3 crop production magazine february 2023

Opinion

Smith’s Soapbox - Views and opinions from an Essex peasant…

Nature Natters - A nature-friendly perspective from a Cambs farmer.

Styles’ Stance - A tongue-in-cheek look at farming.

Talking taties - Plain talking from a Yorkshire root grower.

Last Word - Topical insight from CPM’s Editor.

Cereal agronomy – Inatreq – a headache for 2023?

With new guidance on best practice for Univoq, we find out how it’s being received.

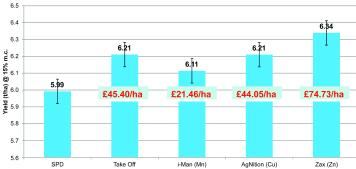

Sustainable solutions – Playing NUE detective

Getting the most out of nutrition involves following the clues to improve NUE.

Biostimulant usage survey – Looking to 2023

We find out how, what and why you may be using biologicals or biostimulants this season.

Agri-tech – Growing tall to nano small

A look at the future of nanobubbles and vertical farming technology in UK agriculture.

Genetic technology – A special relationship

Gene-edited barley trials demonstrate the interaction between the crop and soil microbes.

Agroecology Conference – Making the transition

Real

Results Pioneers – Contemplating knee-jerk barley

A chance crop of hybrid barley is causing a Yorkshire grower to reconsider his cropping options.

Innovation Insight – Apprehending the hidden thief

We find out how a plant breeder has bred for resistance to Verticillium is a disease without any fungicide options.

Cabbage stem flea beetle – Outsmarting the beetle

Results from the first year of NIAB’s csfbSMART project throws new light on the pest.

Theory to Field – New tools for post-insecticide era

New tool aims to provide growers with better risk-management info for wheat bulb fly

Managing uncertainty – Steering through unchartered waters

With market and input price volatility, we find out how to build resilience with spring barley.

Oxford Farming Conference – Farming a new future

Highlights from the first day of farming’s most prestigious meeting of minds in Oxford.

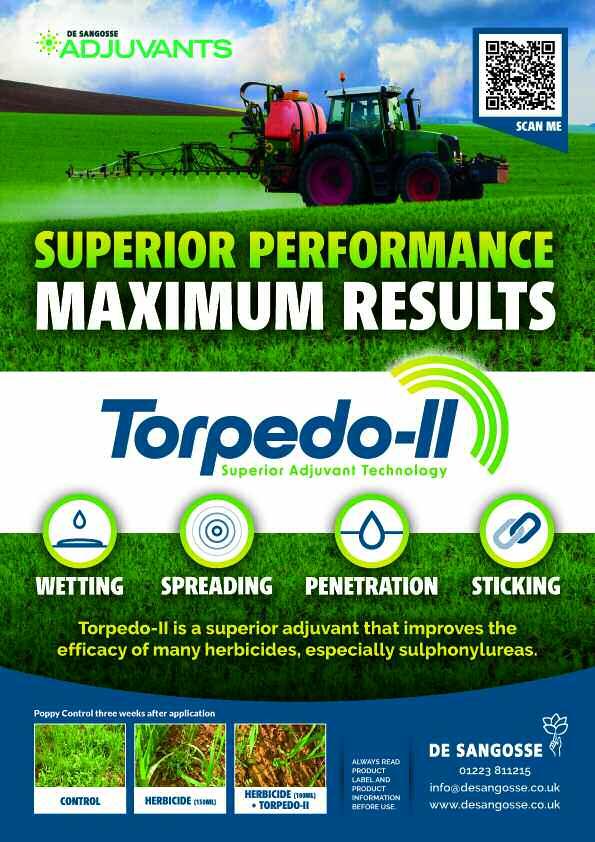

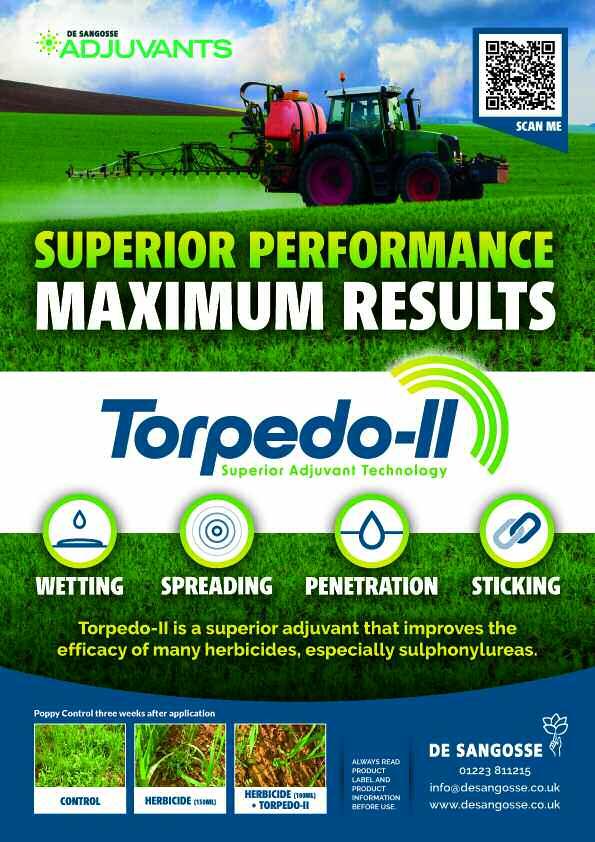

Pushing performance – Achieving with adjuvants

Choosing the right adjuvant for the job in hand is crucial for best results. We find out how.

Crop nutrition – The functionality of soils

A nugget from AHDB’s Agronomists Conference which considers the world beneath our feet.

Crop nutrition – Lightening the N footprint

Three growers are looking at how they can use N more efficiently with the help of a digital tool.

Bioscience in practice – Maximising efficiency

Supplementing natural processes provides a way to help the crop help itself to nutrients.

Things to consider when on the agroecology path, from those early steps to the more advanced.

Regen Pioneers – A road less travelled

Joel Williams outlines ‘Efficiency, Substitution and Redesign’ as a route to agroecology.

Carbon trading – Eliminating asymmetry

A look at how to align interest and caution when considering trading the farm’s carbon.

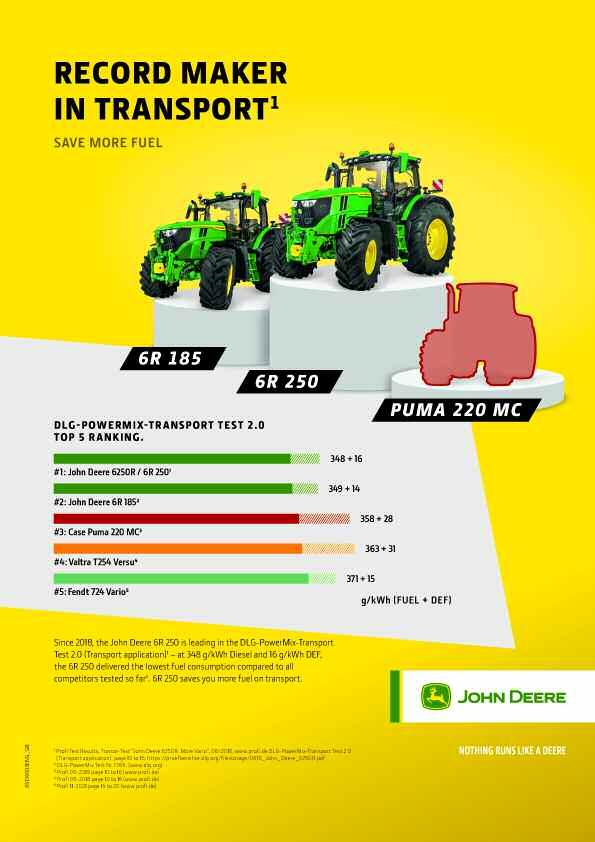

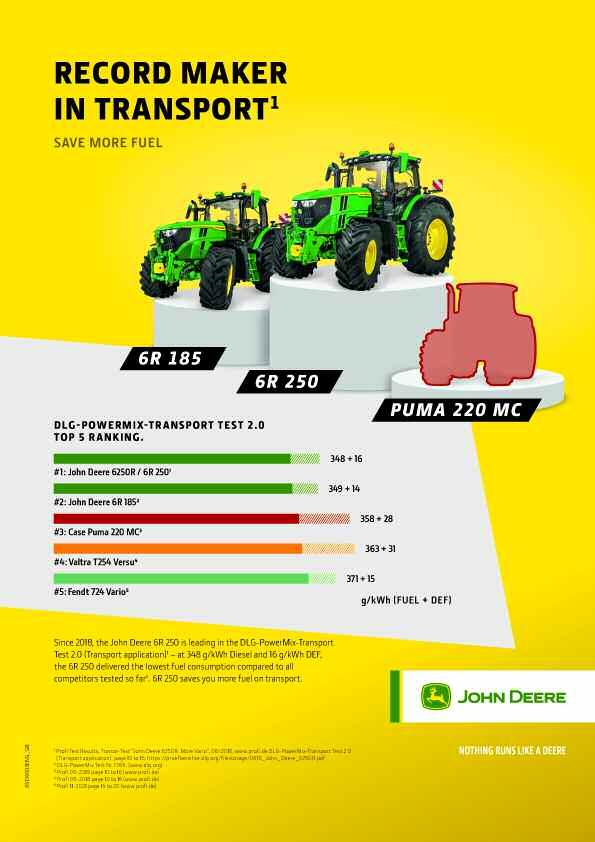

LAMMA 2023 – The storm before the calm?

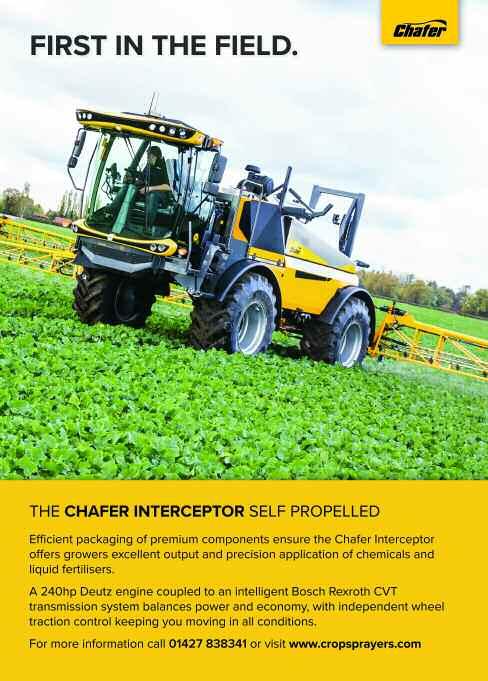

Highlights from the LAMMA Machinery Show, which had plenty of interest on offer.

On Farm Opinion – The seeds of a new way on weeds

We find out how a Redekop seed control unit is bashing grassweeds into shape.

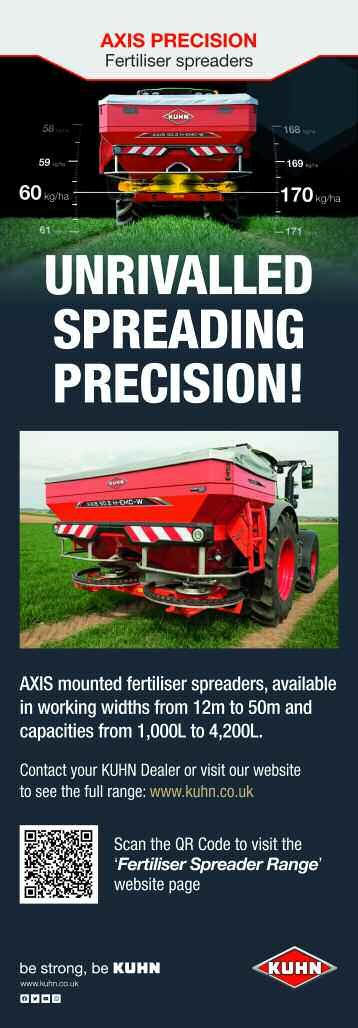

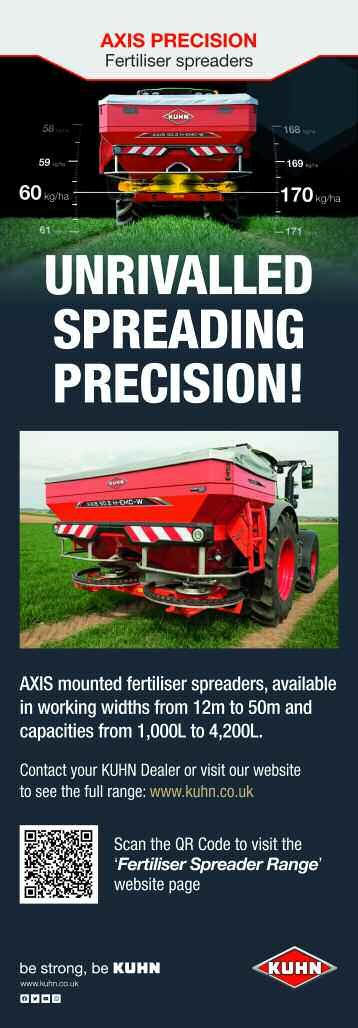

Fertiliser spreaders – Weighing up for accuracy

A look at some of the new spreader models available which a im to improve efficiency.

CUPGRA Conference – Change required from top to bottom

Highlights from the annual CUPGRA Conference where potato barons gathered in December.

Potato agronomy – Cease and Decyst

We visit a farm where trap cropping is being investigated to help reduce PCN populations.

Seed treatment – Rolling their eyes

Two Cornish farmers have moved to a roller table to treat seed tubers before planting.

14 72 79 103

6 65 96 106 107

Machinery 66 69 72 76 79 84 89 97 100 103 Sustainable farming Roots Technical 7 14 20 26 29 33 37 41 45 47 50 52 58 62 In this issue 5 crop production magazine februar y 2023

Would you credit it?

I’ll confess we have somewhat unkempt hedges on this farm. I’ve never been one for an annual campaign of recreational flailing with the hedge trimmer. Aside from the ones that overhang highways,our hedges will only be cut once every three to four years.

Some farmers will view this as neglectful laziness, whereas I see

it as advanced hedge management –– although, if I’m honest, I’ll admit I do have a character flaw that makes me prone to thinking up reasons not to do things rather than exerting myself to get off my backside. For example, when the kids were babies, I used to convince myself it was sometimes better just to leave them crying in the cot as a way of teaching them self-reliance. Leaving my many parental failings to one side, let’s get back to hedges and their management or, as some may call it, lack of management. There have always been valid reasons not to routinely cut hedges in the autumn and winter. One good one being that the haws on the hawthorn in its winter rouge provide a larder for birds, such as finches and

thrushes, that are facing a seasonal shortage of food. To my mind these little scarlet calorific avian treats are best left in place rather than scattering them to the four winds before they had time to mature.

Aside from this feeding of the peckish flocks, there is also the highly fashionable goal of carbon capture. Hedges like trees absorb carbon so –– to my simple mind –– the more mass they have, both above and below ground, then the more carbon they will sequester. But there is a complication in this logic in that careful pruning can encourage new vigorous growth, which in turn will sequester more carbon. Regular cutting could encourage more growth and lay down more carbon through the spent trimmings being mixed with soil they fall on.

On the other hand, hedges that are annually whacked back to denuded three-foot stumps aren’t going to be doing much business in the carbon exchange. But somewhere in the middle ground there may be an optimum. I’m not aware of any research on this. Maybe it should be done.

And when we discuss carbon nowadays in terms of practical far m management, you can be sure it won’t be long until someone mentions carbon credits. I don’t suppose I’m the only farmer who is looking at the potential of selling carbon credits with a sense of jeopardy. On the one hand, a smart business should utilise all its assets to create profitable income streams. This seems even more keenly felt now that BPS is going the way of the dinosaurs. If by fine tuning our farm management we can monetarise it by creating carbon credits, then what’s not to like?

But on the other hand, it does feel this trick of creating carbon credits through somewhat

Guy Smith grows 500ha of combinable crops on the north east Essex coast, namely St. Osyth Marsh –– officially the driest spot in the British Isles. Despite spurious claims from others that their farms are actually drier, he points out that his farm is in the Guinness Book of Records, whereas others aren’t. End of.

creative carbon accounting has elements of being the latest scam soon to be bracketed with PPIs and Volkswagen’s ‘emissionsgate’ scandal. I recollect in the early days of renewable energy subsidies that it could pay to shine electric lights onto solar panels. Furthermore, there are some ethical questions when it comes to the buying and selling of carbon credits in order to absolve or justify a polluting activity Getting on a jet plane with a clear conscience because the airline reassures you it has stopped someone cutting down a bit of rainforest seems as dodgy as the medieval trade in religious pardons –– whereby you could commit your favourite sins, safe in the knowledge that if you were rich enough to buy a pardon then you would still gain entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

At the end of the day coveting your neighbour’s wife should stay in the ‘do not do’ drawer, irrespective of what dodgy coupon you might have purchased. Similarly, if you want to contribute to a society-wide attempt to reduce the use of fossil fuels, then it’s probably best to not take too many air flights –– even if someone in the Amazon rainforest has been persuaded to keep their chainsaw in its sheath.

@essexpeasant

6 crop production magazine februar y 2023

Inatreq – a headache for 2023?

Cereal agronomy

Corteva has recently issued detailed best practice application advice for Inatreq-containing fungicides for the coming season after worrying problems were reported by spray operators in 2022,its first season of use. But will farmers follow it? CPM reports.

By Mike Abram

By Mike Abram

It was slap bang in the middle of the wheat flag leaf spray window when farming social media started to explode with worries about recently approved fungicides containing new active ingredient Inatreq,such as Univoq (fenpicoxamid+ prothioconazole). Problems were being reported by farmers and sprayer operators, who were asking whether anyone else had had issues with degradation of nozzle O-rings and diaphragms after spraying T2s containing the new active.

It was the last thing anyone in the industry would have wanted for the promising new fungicide, which is the top performing active against key wheat disease septoria according to the latest AHDB Fungicide Performance trials. But there were seemingly plenty of farmers who had experienced issues, with a small minority also expressing

concern over degradation to pump diaphragms.

Corteva immediately issued statements suggesting growers increase water volumes to as near to 200 l/ha as practical and to reduce the number of products in any tank mix. It also reminded sprayer operators to observe best sprayer practice, especially concerning clean out procedures.

Investigating the cause

An investigation was also initiated, with a team of Corteva technical experts and field scientists assembled to work together with distributors, equipment manufacturers, sprayer operators and growers to try and get to the bottom of the problems reported on the ground.

The firm says all farms affected were contacted as part of the investigation, as well as farmers who used the products successfully, in order to try and find a root cause. Most farmers who used the product encountered no problems, according to Corteva, and experienced good disease control.

A faulty batch was quickly ruled out by the manufacturer, and in a statement to CPM it said: “The issue is believed to be due to a complex of factors, which is why it did not occur during the wide range of applications made during development and the early stages of commercialisation. To date, extensive investigations indicate sprayer parts are only affected when a number of factors converge.”

These factors include (see box) the type of material and age of sprayer seals and diaphragms, the concentration of the spray

solution, how long it is in contact with the sprayer parts, and sprayer operator practice – especially around wash out procedures.

While the investigation was not complete at the time of writing, those findings had led Corteva to issue detailed best practice application advice for using Inatreqcontaining products this spring.

The advice splits into two main areas: winter maintenance and in-season best practice. Over the winter Corteva is recommending that sprayer operators replace pump diaphragms with new ones, ideally made with Blueflex or NBR, as well as the diaphragm seal in the Ramsay box and anti-drip diaphragms, again with EPDM where possible. It also suggests operators can modify air shut off anti-drip valves to use Teflon replacements.

If it’s not possible to replace anti-drip

“

The company appears to have buried its head in the sand over the problem and is suggesting it’s everyone else’s fault. ”

7 crop production magazine februar y 2023 ▲

Tom Robinson says it’s impossible to clean out a sprayer completely because of the circulator y system.Typically there’s between 0.5-1% left in the sprayer’s pipework when the tank is empty.

Cereal agronomy

Cleaning out the spray tank and flushing the lines as fully as possible is important when using Inatreqcontaining products.On Andrew’s sprayer the clean water tank is one-tenth of the volume of the main tank,and he’s able to time emptying one-third of the clean water tank into the main tank.He then sprays out that water and will stop when air is coming out of the nozzles,having got the sprayer as clean as he can with the first rinse load.By repeating that process a further two times,it ensures the cleanest possible rinse with the smallest amount of water.

diaphragms with EPDM or Teflon, it suggests replacing all pneumatic/automated anti-drip diaphragms/pistons before spraying products containing Inatreq and checking these after use.

During spraying Corteva is recommending a minimum spray volume of 200 l/ha. If lower water volumes are used, then the spray concentration should not exceed 0.7%. Spray solutions should not be left in the spray tank overnight, and the tank, pump and lines should be rinsed at the end of each day’s spraying.

Has this happened before?

Inatreq isn’t the first product to have similar problems attributed to it,says Tom. Both Tilt (propiconazole) and an early formulation of sugar beet herbicide Betanal (phenmedipham) had similar issues.

With Tilt it was a solvent in the formulation which attacked the rubber diaphragms,at the time were all made of EPDM.Switching to ones made of Viton solved the problem and have become more widely used ever since.

“It’s unfortunate that in this instance EPDM seems a more resilient material to Univoq than Viton,”suggests Tom.

While Corteva deny this was a problem identified before last season,one Twitter user suggested last spring that he had experienced similar issues while trialling the product for Corteva,and separately two CPM sources have suggested trials officers had noticed syringes not lasting as long when being used to measure out Inatreq products for trials.

That last point is critical, according to independent spray consultant Tom Robinson, who has been part of the investigation team.

“Everybody who has passed their PA1 and PA2 sprayer training should remember that daily cleaning is a requirement for reliable performance and passing the test, but not everybody does it in practice.”

Good practice

“I can’t comprehend when operators don’t wash sprayers out because no spray mix is going to be a tonic for the inside of a sprayer. The most important thing of all is washing out at the end of every day, and doing it properly,” he stresses. “It’s the starting point for a long life for your sprayer.”

That’s a point reiterated in a video Corteva has made with Tom and sprayer operator Andrew Myatt of Stowell Park Estate in Gloucestershire.

“It’s impossible to clean out a sprayer completely because of the circulatory system,” says Tom. “Typically there’s between 0.5-1% left in the sprayer’s pipework when the tank is empty. What we are doing when washing out is diluting the chemical left in the machine.”

The best way of completely flushing the system is to start by spraying out the spray mix completely in the field, and then splitting the water in the clean water tank in three equal parts. In Andrew’s sprayer the clean water tank is one-tenth of the volume of the main tank, and he’s able to time emptying one-third of the clean water tank into the main tank.

“He then sprays out that water and will stop when air is coming out of the nozzles,

having got the sprayer as clean as he can with the first rinse load.”

By repeating that process a further two times, you ensure the cleanest possible rinse with the smallest amount of water, says Tom. “The amount of chemical left in the pipework after a triple rinse is 20 times less than if the sprayer is rinsed with the same volume of water transferred in one shot.”

Preventative winter maintenance is also good practice, he suggests. “It’s always better to change things, like diaphragms, before they start leaking, and how long they will last will depend on the general washing out maintenance.”

The advice from Corteva is “belt and braces”, he admits. “They don’t want anyone to have any problems and if you follow their recommendations, you really shouldn’t have any trouble.”

Most sprayer operators would expect to get 3-4 years out of a pump before changing diaphragms, depending on area covered, says Trevor Johnson, managing director of Acare Services, which supplies sprayers, servicing, parts and accessories.

“Sprayer operators typically only change

Contributing factors

Factors Corteva says could converge to cause sprayer damage when using Inatreq products:

● The materials of the sprayer seals and diaphragms

● The age of the sprayer seals and diaphragms

● The concentration of the spray solution

● The duration of contact between the spray solution and seals / diaphragms

● Individual user practices and adherence to guidelines / traditional sprayer hygiene good practice

David Lines says that contractors in his area are unlikely to use Inatreq-based products as they can’t risk the downtime.

8 crop production magazine februar y 2023 ▲ ▲

Virtually every nozzle blocked after using Univoq last season,despite a meticulous cleaning process,says Roger Wilson.

pump diaphragms when they notice they have a pressure drop rather than as part and parcel of a normal service routine. It’s unlikely we will see a change in mentality,” he predicts.

That’s partly due to the cost of a full pump service, including changing diaphragms and valves, which can set growers back by £800 to £2000, depending on the sprayer A do-it-yourself change of typically six diaphragms on a pump would be much cheaper –– each diaphragm on average costs around £28, although some brands can be more expensive, he says.

A Ramsay Box replacement kit costs £55 to £185, depending on manufacturer, while replacement anti-drip diaphragms, whether DCVs or O-rings, cost around £1-3 each, adds Trevor.

He suggests that it might be worth having a set of spares available during the season in case of any issues.

At a minimum, following the Corteva

maintenance guidance will cost from £300, but Tom suggests sprayer operators should perhaps be changing these components more often than they currently do.

“If you wait for them to fail, the farm will lose more money in downtime than taking the time to change them beforehand.”

But it does create an incentive to look at alternative products, which don’t have the same maintenance obligations, so how will the industry react?

Industry reaction

Independent agronomist David Lines, based in Herefordshire, says his clients are happy to use Inatreq-based fungicide on around two-thirds of the wheat area he advises on. “They are mainly the ones that didn’t have an issue or have read the guidelines and are happy to use it.”

The other third is mostly sprayed by a contractor, who had a minor issue last year, but isn’t prepared to risk the downtime this year, preferring to wait to see what happens this season, says David.

Those who plan to use Inatreq are unlikely to follow the maintenance advice, given they didn’t see any problems last season, but will likely raise water volumes to 150 l/ha to comply with the 0.7% concentration target, despite some unhappiness at needing to do this, he adds.

Decisions to not follow the guidance are likely to be at a grower’s own risk, he suggests. “Corteva has come out with a set of guidelines and if you’re not prepared to follow them, and you use the product, it’s at your own risk.”

Wiltshire grower Roger Wilson says his experiences last season and the new guidelines are making him think twice about using an Inatreq-based product this spring.

Virtually every nozzle was blocked the

Why has Corteva made these recommendations?

Evidence from the investigation found that damage to rubber components was more likely to occur at spray concentrations above 0.7%, which is why Corteva is recommending higher water volumes that are below that level,or ideally to use 200 l/ha.

“For growers who normally apply fungicides at lower water volumes,this will slow the operation down,”says Tom.“This is not ideal, but ultimately Univoq is a good product that growers will want to use.Hopefully this is a short-term mitigation while an alternative formulation can be developed.”

There is some contradiction in Corteva’s water volume advice. Currently showing on its

website, it’s still recommended to apply in 200 l/ha water for doses above 1.45 l/ha even though spray concentrations will be above 0.7% concentrations.

A component trial is part of the evidence supporting the recommendations around sprayer maintenance. One method of testing for problems with rubber components is putting them in a spray mix and looking for shape or weight changes, explains Tom.

Corteva also used spray rig tests. “These tests showed that brand new components showed much less change than ones that had already been used.”

next time he went to use his sprayer after using Univoq, he says, despite a meticulous cleaning procedure.

“What they are suggesting you do over winter isn’t going to come cheaply and will take time to do as well. It’s not a very user-friendly product.”

After a relatively dry spring with low disease pressure last year, it was also difficult to gauge whether the hassle was, or will be, worth it in terms of product performance, he adds.

“We used it because the trials suggested it would give an uplift in effectiveness, but it wasn’t really a year to show it was so good that it was worth all the hassle. I’m certainly thinking twice about using it again,” he says.

“I’m also not impressed with Corteva, the company appears to have buried its head in the sand over the problem and is suggesting it’s everyone else’s fault.”

Suffolk grower Ed Banthorp is more likely to use Univoq again, despite a few issues with Chemsavers going last spring while spraying the majority of his 600ha wheat with the new fungicide at T2.

“Compared with some people, we were incredibly lucky –– I’ve been told of some horror stories. But we had all the diaphragms in the pump changed in mid-April, so if they hadn’t been brand-new maybe we would have suffered more.”

Like Roger, he says it was difficult to judge performance last year but feels it would be a shame to write off a new active and will likely use Univoq again this spring.

Most of the sprayer maintenance has been done recently, but the farm will follow washing out procedures more closely Spraying at higher water volumes would be a pain, he admits. “It will be a shame to have to go at a higher water volume –– we typically spray fungicides at 100 l/ha –– so

Ed Banthorp used Univoq last season at low water volumes without any serious issues and is likely to risk spraying at 100l/ha,unless widespread problems are reported again in 2023.

Ed Banthorp used Univoq last season at low water volumes without any serious issues and is likely to risk spraying at 100l/ha,unless widespread problems are reported again in 2023.

10 crop production magazine februar y 2023 Cereal agronomy ▲ ▲

Cereal agronomy

North Yorkshire farmer Thomas Simpson also had issues with nozzles dripping and blocking after using Univoq, albeit on a sprayer where the nozzle diaphragms were getting old. Despite some down time, he carried on using the product across 360ha of wheat.

On the fence

For this season he’s on the fence about using it, after a new Horsch sprayer arrived on farm. That should mean he’s covered for the overwinter maintenance, which he describes as a lot to do just to use Univoq, but says he wants more clarity over what the problems are to decide whether to use it or not.

About 10% of users reported problems to Patrick Stephenson,who reckons that those who used Univoq last year without issue will probably continue to do so,but he sees the sprayer compatibility issues as a big hurdle for some.

that will double the amount of time it takes us to get round. Having got away with it once, we might risk it, but if we hear of people having problems again then maybe we will change.”

A new star is born

A ‘new’ post-emergence herbicide will be available to wheat growers this spring as Bayer announces its latest evolution of Atlantis (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron) with the approval of Atlantis Star,which contains a third ALS-inhibitor, thiencarbazone-methyl.

The newly approved herbicide doesn’t promise revolution for post-em blackgrass and ryegrass control but instead an incremental improvement in performance over its Atlantis-derived predecessor,Pacifica Plus (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron+ amidosulfuron).

Although both herbicides contain three actives that are ALS-inhibitors,thiencarbazone-methyl (TCM) isn’t a sulfonylurea,it belongs to the chemical class of sulfonyl-amino-carbonyltriazolinones so there could potentially be a small metabolic resistance benefit,says Bayer’s Tom Chilcott.

Tom believes that it’s becoming more and more important to look beyond herbicide actives and consider their mode of action (MoA) so that we become much better at alternating different MoA in herbicide programmes to avoid driving selection pressure for resistance.

“Atlantis Star offers a slight improvement in blackgrass (5% over Pacifica),brome,ryegrass and wild oat control,with extended broadleaf weed control which includes speedwells,

“Our sprayer wasn’t cheap, so I don’t want to damage that, but equally it’s a good product. Corteva seems to be covering its back to make it your problem if you use the product. I think they should be a bit clearer to encourage you to use the product.”

Yorkshire AICC agronomist Patrick Stephenson says that within his client base around 10% had some problems last season, which he thinks is probably reflective of the wider industry,

although perhaps only 1% resulted in formal complaints.

“We need the active, but the issues around its sprayer compatibility are substantial hurdles. Those people who used Univoq last year and had no problems will probably use it again, while some bigger contractors or larger farms will probably veer away from it,” he says.

He says Univoq is unlikely to be used at T1 because of the bigger tank mixes used at that timing. “But I don’t think there will be enough of the next best product, Revystar (fluxapyroxad+ mefentrifluconazole), in the system, and I’m also nervous whether that will be robust enough if we have a very wet April and May.”

That should point to Univoq being used at T2, but Patrick thinks many growers will choose an alternative if they can, partly because of the water volume and overwinter maintenance required.

“If you’re planning on getting maintenance done and you’re think of using Univoq, don’t stint on anything and get it done while you have the chance, rather than waiting in-season and finding you have a problem.” ■

dead-nettles,pansy,poppy,bindweed and cranesbill,”he says.

While Atlantis Star plus Biopower holds its own with blackgrass and ryegrass,it’s bromes where the most significant improvement in control is seen, with the Bayer Chishill weed screen data (2017-2022) indicating a 10% uplift over Pacific for meadow brome and 20% for rye brome species.

Uptake of TCM is mostly foliar,though some residual activity remains which facilitates some activity on germinating seedlings,though root uptake is very limited –– especially in dry soils, explains Tom.

It’s also an active which is non-volatile and photo stable but has high soil mobility (water solubility = 998 mg/l) and is rapidly degraded in soil by a combination of microbial breakdown and chemical hydrolysis.

Atlantis Star can be applied from 1 February from GS21 up to before GS33.At the full label rate of 0.33 kg/ha,Atlantis Star delivers the same amount of mesosulfuron as Pacifica Plus without the additional restrictions Pacifica has relating to timing,application technique and following crops.This means that a full rate of Atlantis Star can be used for early weed control where an equivalent rate of mesosulfuron as Pacific Plus can’t be applied until 1 March.

For those who have blackgrass to tackle this spring,a new post-emergence herbicide, Atlantis Star,may provide a little extra control but it’s evolution not revolution.

Tom adds that Atlantis Star can be tank-mixed with a wide range of herbicides to provide additional protection from additional weed germination and widen the spectrum of broad-leaf weed control. It can also be mixed with fungicides if farmers are looking to combine a T0 or T1 spray with weed control.

The Bayer advice is to apply Atlantis Star plus Biopower alone for best results,but the physical and biological compatibility of tank-mix partners is available on the Bayer website.

12 crop production magazine februar y 2023

▲

Real Results Pioneers

Contemplating knee-jerk barley

A knee-jerk reaction to grow winter barley when it became clear the conditions and calendar were going to threaten successful oilseed rape establishment last season has opened Pat Thornton’s eyes to the potential benefits of the crop in the rotation.

According to Pat, it was going to be too dry to drill oilseed rape in August 2021 at his 150ha Low Melwood Farm, near Owston Ferry –– just 20 miles east of Doncaster.

“It was obvious I was up against it, in terms of how dry it was, and looking at the calendar it was going to be a task to get a decent crop,” he explains.

“So after making the decision not to go ahead with OSR, I started looking at alternatives as there was certainly an opportunity to get something into the ground. Winter barley looked the best option, not least to create an earlier and longer window for drilling OSR this season.”

The hybrid feed variety SY Kingsbarn was chosen after discussions with a local agronomist, with its high yield potential and decent specific weight attracting him. While in variety trials, it has as wide a yield range

as any winter barley variety, the range falls much higher on the graph in terms of total yield, he says.

A malting variety wasn’t an option with previous experience with spring barley grown on the farm suggesting it would be difficult to meet grain nitrogen spec.

“We grow out and out feed –– it’s just not worth the risk of anything else,” comments Pat.

Tackling blackgrass

He followed the breeder’s recommendations for a seed rate of 200 seeds/m2, drilling the crop on 24 September. A pre-emergence herbicide stack of Liberator (diflufenican+ flufenacet) plus Defy (prosulfocarb) plus Stomp Aqua (pendimethalin) was applied across the field for blackgrass control.

In most of the field blackgrass is reasonably under control –– helped with the strategies Pat has put in place, including growing spring barley –– but there’s a 4ha patch where the blackgrass is more difficult, he says. “That area is a little wetter with a heavier soil type and the crop establishment wasn’t as good –– perhaps 85% of the target plant population.”

Hybrid barley is sometimes marketed on the basis that its competitiveness can help swamp out blackgrass, he notes. “In hindsight it has made me wonder just what crop competition would have done without the herbicide knock it suffered, because I’d opened the canopy even more with the treatment and the crop took a backward step [in competitiveness].

“It wasn’t a disaster –– blackgrass was hardly visible in June, so we’d got on top of it. In the low to moderate areas in the rest of the field, the crop did a reasonable job,

although not as good at breaking the lifecycle in the way you can with spring barley.”

A dose of ammonium sulphate in early March, once there was crop growth, helped keep crop competition high for blackgrass suppression. That was followed with 60kgN/ha urea to promote and maintain tiller numbers to help maximise yield, he says.

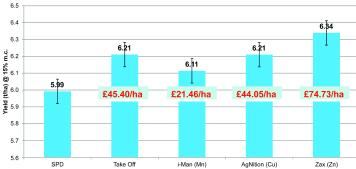

Given the relatively low disease pressure seen visually in the trial,the relatively big difference in yield between fungicide treatments was a surprise,says Pat Thornton.

After careful consideration of what was a knee-jerk reaction,a last-minute alternative to oilseed rape provides food for thought for a North Lincolnshire grower. CPM reports.

By Mike Abram

Winter barley looked the best option,not least to create an earlier and longer window for drilling oilseed rape this season. ”

“

14 crop production magazine februar y 2023 ▲

Pat Thornton,SY Kingsbarn winter barley trial at Owston Ferry

*Estimated yields by ADAS Agronomics

**Winter barley price:£250/t; Fungicide costs from 2022 industry panel

Relative likelihood of yield benefit from BASF treatment

Source:BASF,2022

against rhynchosporium, while pyraclostrobin is the best strobilurin for the mutated strains of net blotch [that are difficult to control],” she explains.

“At the T1 timing, the biggest issue is usually rhynchosporium and net blotch, so for this threat and keeping disease low, the combination is perfect.

“By adding prothioconazole on top, we also cover the risk of mildew as well as adding extra control of rhynchosporium, making it a very good three-way combination.”

The co-formulated Tevos plus Innox (prothioconazole) will be widely available as a co-pack option for the coming season, she notes.

Relative likelihood of a BASF yield benefit of different sizes,according to the Agronomics analysis of this trial.

*Winter barley price:

In total around 185kgN/ha was applied to the crop during the growing period.

“I was confident I could keep the crop standing so I was more thinking about maximising yield, but with the blackgrass at the back of the mind as well.”

Kingsbarn’s disease weaknesses are net blotch (rated 5 on the AHDB Recommended List) and brown rust (5). It also has moderate susceptibility to rhynchosporium (6). Brown rust was the disease most easy to find as the crop approached the

Variable rate nitrogen interest from xarvio trial

Pat’s interest in the potential to variably apply fertiliser has been piqued after taking part in a joint BASF and Amazone trial using BASF’s digital platform xarvio on the farm.

Insight gained from satellite-sourced normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) imagery and yield data was used to create a xarvio powerzone map that split a winter wheat field into five different zones.

Those zones were used to drill the field using seed rates that varied by 15-20% using tined and disc Amazone drills,and to variably apply nitrogen using in-season biomass data.

“It was an interesting exercise,” Pat says.“My view is that on a farm of our scale we don’t really want to mess about too much

xarvio was used to produce a powerzone map that split a field of winter wheat into five different zones and nitrogen was variable applied using in-season biomass data.

with variable seed rates.

“But with the way fertiliser prices are going,variable rate fertiliser was interesting in terms of the potential savings with the xarvio maps.Over the course of the season,there seemed to be a levelling up effect across the field and took out some of the range of results we’ve seen in previous years.”

key T1 (GS30-31) timing in early April, says Pat.

With little winter barley grown on the farm in the recent past, the field was a good opportunity to gain knowledge and compare key fungicide products for the crop in a BASF Real Results farm-scale tramline trial.

The comparison in the trial was between long-standing market leader Siltra Xpro (bixafen+ prothioconazole) and newer BASF treatment Tevos (pyraclostrobin+ fluxapyroxad) plus Innox (prothioconazole) at T1.

Both sets of tramlines were treated with Revystar XE (mefentrifluconazole+ fluxapyroxad) at T2. That timing suits Revystar with mefentrifluconazole’s relative strength against ramularia, suggests Aliona Jones, agronomy manager for BASF in Pat’s region. Tevos, on the other hand, is more suited to the T1 timing, with its combination of fluxapyroxad and pyraclostrobin, she says.

“Technically, it’s a mix of two very good actives in barley. The SDHI Xemium (fluxapyroxad) is an extremely strong active

In the trial, which used standard commercial rates of Siltra Xpro (0.45 l/ha) and Tevos (0.4 l/ha) plus Innox (0.4 l/ha), disease remained visually low during the season, says Pat.

A disease assessment was due to be made on 28 June, but like many crops last summer, warm dry weather in late June caused rapid senescence so that the trial couldn’t be assessed. Despite that, as the majority of the crop senesced rapidly Pat thinks the Tevos-treated tramlines hung on a little longer. “You could start to see slight differences in the treatments,” he notes.

That difference became more evident when the combine went through. The yield data was analysed using ADAS Agronomics, which helps clean the data by removing headlands, any anomalous combine runs when the header might not be full or spans both treatments and locally extreme data points. The data is also corrected for offsets created by changes in combine direction.

Statistical analysis is then used to estimate treatment effects and associated standard errors. In this case, the farm standard Siltra programme yield was measured as 11.05 t/ha ––higher than the true average due to the exclusion of headlands, while the Agronomics analysis estimated that the BASF

Treatment Field comparison BASF treatment T1 (8 April) Siltra Xpro (0.45 l/ha) Tevos (0.4 l/ha) + Innx (0.4 l/ha) T2 (27 April) Revystar (0.5 l/ha) Revystar (0.5 l/ha) Yield 11.05 t/ha 12.29t/ha MOIC v farm standard treatment** £300.80/ha

Yield benefit or loss relative to Field comparison Probability MOIC v farm std trt* >(Greater than) 2.00t/ha 6% (very likely) >£490.30/ha >1.75t/ha 15% (very unlikely) >£427.80/ha >1.50t/ha 30% (very unlikely) >£384.70/ha >1.25t/ha 49% (about as likely as not) >£302.80/ha >1.00t/ha 69% (likely) >£240.30/ha >0.75t/ha 84% (likely) >£177.80/ha >0.50t/ha 93% (very likely) >£115.30/ha >25t/ha 98% (very likely) >£52.80/ha >0.00t/ha 99% (virtually uncertain) >£9.70/ha

£250/t; Fungicide costs from 2022 industr y panel

Source: BASF, 2022

16 crop production magazine februar y 2023 Real Results Pioneers ▲ ▲

treatment increased yield by 1.24 t/ha.

With the variation in the yield data, ADAS is 90% confident that difference ranges from 0.43 t/ha to as high as 2.05 t/ha, with 1.24 t/ha as the best estimate, says ADAS research consultant Susie Roques, who manages Agronomics trials.

In this case, the statistical model suggested the yield benefit in the trial was unlikely to have been the result of underlying soil variation, she confirms.

The analysis also gives growers a guide, based on the trial result, of the probability of different levels of yield response. Susie says the analysis’ best estimate (1.24 t/ha) has a 50% probability of occurring, with higher yield responses becoming more unlikely, and lower yield responses more likely (see table).

“If we think our estimation of the treatment effect is 1.24 t/ha, then we’re pretty sure it is over 0.5 t/ha –– hence the 93% probability,” she says.

The table is intended to be used in conjunction with relative costs of different treatments to determine the likelihood for an economic benefit, she explains.

While given the relatively low disease pressure seen visually in the trial, that kind of difference was perhaps a surprise, although Pat says he definitely saw a noticeable difference in yield as he was combining the field.

Aliona says it wasn’t the only result like this, however. “We had a few trials which were similar, and in all the barley trials I think growers are convinced of the value of Tevos treatment.”

But what was behind the yield increase? Aliona suggests both the physiological and disease control benefits from pyraclostrobin and fluxapyroxad could have been playing a part in the dry spring and summer period.

“In barley, physiological effects are even more important than in wheat, for example,” she claims. “It’s one of those crops where you only have to breathe on it and it starts yellowing. So keeping stress out is extremely important.”

That’s particularly important for ramularia, she points out. “Keeping the crop clean as long as possible delays the switch in the ramularia pathogen from being a benign fungus in the barley plant into a pathogen.

“The moment the crop gets stressed, the switch happens as ramularia is already in 80% of barley plants, so keeping the crop clean from disease is important as that will cause stress, and that’s obviously a strength of both pyraclostrobin and fluxapyroxad.”

Fluxapyroxad also has a physiological effect that will help the crop during period of

dry weather, she notes. “It’s helps regulate the opening and closing of the stomata in the plant and controlling water loss, so if there is drought Xemium has this positive physiological effect.”

If the effect of the treatment was to keep the crop greener for longer, as Pat thinks, that will also have contributed to extra grain fill and higher yields.

Despite the success of the winter barley crop, Pat hasn’t planted any for the coming season. The early harvest gave him an extra two weeks over wheat for a good entry into OSR, and with rain forecast in mid-August he was able to drill the crop just before it came.

“We were able to spread some sewage cake and get it drilled on 10 August, and it’s looking really well –– I think the sewage helped keep flea beetle off, and by the time we got to August bank holiday and peak migration it was well-established and big enough to withstand attack,” he says.

That success has also got him considering whether winter barley should return next season to help give the best entry into OSR, he says. “It was a bit of a kneejerk reaction to put it in, and another one to not grow it.

“But now having seen the data, it will come back, particularly if we don’t get the opportunity to put OSR in after wheat in good time. In the autumn we don’t know the OSR would come up as well as it did, so we’ve got a one-year lag.”

Being able to continue with OSR in the rotation has other benefits including stretching the rotation for his other main break crop, winter beans, which would benefit from a longer break.

Pat says his YEN results highlighted that there was very little in the way of limiting factors for the crop, which was why it yielded

The Real Results Circle

BASF’s Real Results Circle farmer-led trials are now in their sixth year The initiative is focused on working with more than 50 farmers to conduct field-scale trials on their own farms using their own kit and management systems. The trials are all assessed using ADAS’ Agronomics tool which delivers statistical confidence to tramline, or field-wide treatment comparisons –– an important part of Real Results.

In a continuation of this series we follow the journey, thinking and results from farmers involved in the programme.The features also look at

Future Real Results plans

Next year’s Real Results trials are still in the planning,but Pat would be interested in investigating winter bean yields.

“Last year,the top one third of the pods basically died when it came hot.But the top one-third is where the profit is in my opinion.We’re establishing them differently now using shallower cultivations than the plough,pest control isn’t too bad,but we need to be pushing yields.

“We can’t be growing the standard 5-6 t/ha that we were 20 years ago; it needs to be 8.75 t/ha to start competing with other break crops.So yes,I’d like to look a bit harder at how I can keep that top third greener longer and take them through to harvest.”

so well and took advantage of the free resources (eg water, sunlight, etc). But blackgrass would potentially stop the crop being able to take advantage of those things because of either its innate competitiveness or the check from herbicides –– hence wanting to grow it where blackgrass was under control.

“So maybe I was too quick to act and I can see barley coming back. The only caveat is that I would need to be confident on those fields around the blackgrass, because I think the secret from these results was putting the barley crop in the field and not putting anything in its way to stop it. It had all the free resource it wanted, and captured it all, with the fungicides we applied giving it a little extra boost to take the yields to those levels,” he concludes. ■

some other related topics, such as environmental stewardship and return on investment.

We want farmers to share their knowledge and conduct on-farm trials. By coming together to face challenges as one,we can find out what really works and shape the future of UK agriculture.

To keep in touch with the progress of these growers and the trials,go to www.basfrealresults.co.uk or scan the QR code.

18 crop production magazine februar y 2023 Real Results Pioneers ▲

Apprehending the hidden thief

we’re still seeing issues. For the past two to three years, we have been protecting our local trials from cabbage stem flea beetle and this has allowed us to identify a correlation between verticillium resistance and yield, with some popular varieties yielding 20-25% lower than expected when compared with the AHDB Recommended List.”

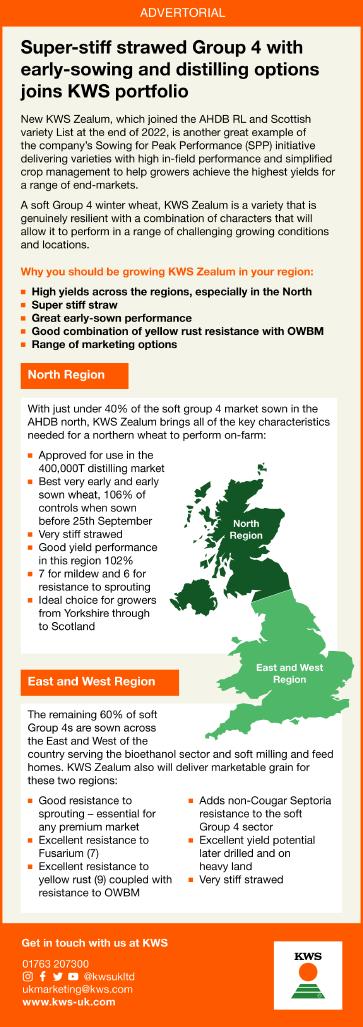

But verticillium resistance has proven to be particularly hard to breed for compared with some other OSR diseases. However, LSPB has produced several innovative new varieties with good quantitative resistance to the disease, with one topping the RL, says Chris.

This came about as part of a wider company aim started by LSPB’s parent firm NPZ. “Once verticillium was identified as an issue, the company wanted to start screening for it in the breeding programme,” explains Craig.

Innovation Insight

Innovation isn’t always about light bulb moments, sometimes it’s a case of joining the dots. CPM gets an insight into how an oilseed rape plant breeder discovered genetics with resistance to verticillium.

By Melanie Jenkins

Breeding disease resistance into new plant varieties has become vitally more significant as access to the arsenal of pesticides gradually tightens and pressures mount for a more holistic approach to integrated pest management. And in some cases,no pesticide options are available at all.

One of those diseases is verticillium, originally named verticillium wilt but renamed in 2016 to verticillium stem stripe due to lack of wilting symptoms in OSR, clarifies Christian Flachenecker, NPZ winter oilseed rape breeder

“Breeding is the main weapon we have against the disease and is a high priority for breeders as there’s no fungicide control against verticillium,” he stresses.

Relative newcomer

Although not a new disease, its history in the UK is relatively recent. OSR was first recognised as a host of verticillium stem stripe in Sweden in 1969 but the disease has only been officially recognised in the UK since 2007, explains LSPB’s Craig Padley.

“The first plant material I saw with ver ticillium was at the OSR congress in Copenhagen in 2003 and I first experienced the disease in the UK at local trials in 2009.”

For LSPB, verticillium has become an increasing issue at the firm’s trial site north of Cambridge, says Craig. “Our typical rotation has OSR one in five and even then,

“The island of Fehmarn in the Baltic Sea had high levels of the disease in the soil making it ideal as a trial site. So we’ve been screening there since 2010 as we can get repeatable scores. From this work, we have been able to identify several lines with good resistance to verticillium and these have been developed for our current and future hybrid offering.”

But even on the island, verticillium symptoms aren’t strong every year, says Christian. So further work has since been done to develop a bioassay in glasshouses, which has given more repeatable results and allowed the firm to supplement its field screening with additional glasshouse trials.

LSPB is routinely screening its hybrids for resistance and has pre-breeding activities undergoing to identify novel sources of resilience toverticillium and other diseases, adds Craig.

Chris Guest and Craig Padley both feel that the impact of verticillium may be overlooked if farmers haven’t grown oilseed rape for several years.

20 crop production magazine februar y 2023

“

▲

Breeding is the main weapon we have against the disease.

”

The hidden thief

Although the highest incidences of the disease are historically seen in the East and central England, says Craig,verticillium has spread far and wide, having been recorded as far west as Herefordshire and north into Yorkshire.

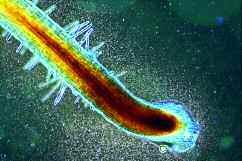

So why is it becoming more widespread? ADAS plant pathologist,Philip Walker explains more about the disease.Caused by the pathogen Verticillium longisporum,it’s a soil borne disease which –– a bit like club root –– can survive for up to 10 years or longer in the soil, he says.

“So once you have it, verticillium is there for a long time –– the disease is ver y persistent.

“The fungus survives as microsclerotia on the previous crop debris. When the next OSR crop is planted, the root exudates stimulate the germination of the fungus which then penetrates the root hairs, surviving in the plant tissue asymptomatically for a long time,”he says.

“When a crop goes through stem extension, the fungus grows into the vascular system and is transported to other plant tissues. A few weeks before harvest,brown striping on the stems become visible,”describes Philip.Now the fungus invades from the vessels and starts to damage surrounding plant parenchyma,leading to

LSPB’s variety Murray has demonstrated good resistance to verticillium.

Research has also involved looking at exotic materials related to OSR, such as cabbage, to try to identify resistant genes, says Christian. “But no single gene has yet been identified that provides significant resistance against verticillium, which has meant it’s been incredibly hard to breed varieties with quantitative resistance to it.

“We have looked for one, and there were

senescence and finally the formation of microsclerotia beneath the epidermis.

In contrast,this systemic spread of the fungus at the early plant growth stages is reduced in plants which exhibit resistance to the disease.

The main issue verticillium causes in OSR is a premature ripening of the plant pre-harvest, explains Craig.“Like phoma stem canker, verticillium switches at one point in its lifecycle to a destructive phase and compromises plant stem performance,leading to reduced thousand seed weight and therefore yield.

“Pre-harvest the disease displays as striping on the stems and branches,as well as premature pod senescence –– they turn black, and seeds don’t develop. Post-harvest it can be seen in the stems as black striping.”

And with the disease still being relatively new to the UK,there’s a concern that the symptoms pre- and post-harvest may be going unidentified, suggests Craig.“We have known growers with promising looking crops that have failed to deliver on expectations,so we’re encouraging agronomists to look at the stems to see if verticillium is present. NIAB can soil test for the disease,but once you know the symptoms it’s fairly distinctive.”

Capable of robbing growers of up to 30% of their yield,losses from verticillium may not be inconsiderable, adds Chris.

And in 2017, the Defra pest and disease sur vey estimated that around 20% of the UK’s OSR cropping had some form of infection, adds Craig. “And I’m pretty sure it has increased since then. The reason being that there’s a prominent movement towards min and no-till practices, which means trash is left on the surface of the soil and could be helping it spread.

“And going back 10 years or so, a lot of growers had quite tight rotations, which may also have exacerbated the issue by feeding the fungus.”

Christian also believes that climate change is helping the disease.“We have found that higher temperatures in the autumn leads to conditions

some hints that there could have been promising genetics in related brassicas, but there’s never been a major resistance gene found. If we discovered one then we’d be able to develop a marker for it, but this still isn’t possible with verticillium which is why field screenings and bioassay testing is so important,” he explains.

“What we believe we have at the moment is a number of genes working together to provide quantitative resistance to the disease.”

more conducive to infection. Warmer autumns might be good for growers as it means they can drill later and still get good establishment but on the other hand this exacerbates fungal diseases such as verticillium.”

It’s also a disease which hasn’t had a lot of work done on it for quite some time,according to Chris. “A lot of the information out there is based on older research but AHDB is doing some work on establishing an index scoring system,however this isn’t publicly available yet.So far,there’s one year’s worth of data and they require two years of data before they can rate the varieties and publish the information on the RL.”

ADAS has been running variety screening trials to identify verticillium resistance for the past 10 years,says Philip.“We know certain varieties do have resistance mechanisms against verticillium spores growing in stem tissues,so they don’t express symptoms,essentially preventing infection.An index score from 1-100 is allocated to varieties based on assessment pre-harvest with the most susceptible varieties scoring 90 or above and those more resistant scoring about 30.We find our assessment method is very reliable in confidently discriminating between the varieties for verticillium.”

Philip Walker says that there are certain varieties which do have resistance mechanisms against verticillium.

Post-har vest verticillium can be seen in the stems as black striping.

22 crop production magazine februar y 2023 Innovation Insight ▲ ▲

No single gene has yet been identified that provides significant resistance against verticillium,according to Christian Flachenecker.

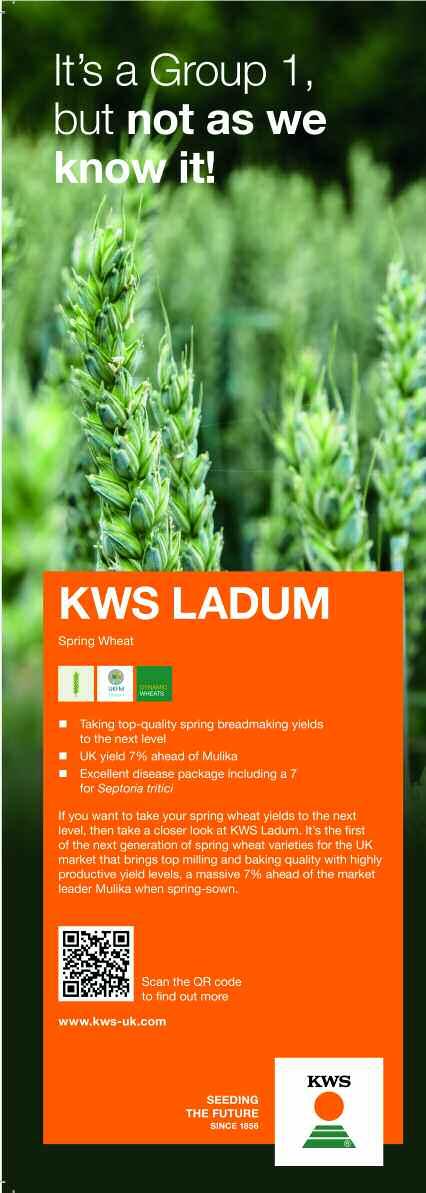

LSPB’s latest variety, Turing, has demonstrated a high level of resistance to ver ticillium and has topped the UK RL for gross output, at 107%, according to Christian.

Murray –– with 106% on the RL for the East/West region only –– is another variety which has demonstrated good resistance to ver ticillium, while Vegas –– 105% UK gross output on the RL –– has medium resistance.

“With all three of these varieties, growers don’t need to fear verticillium too much as they’re among the best on the market for resistance,” says Christian. “Our Cambridgeshire site had the hardest attack by ver ticillium last year it had experienced

A view from the field

As many growers return to oilseed rape for what might be the first time in a number of years, they’re being advised to not forget the lurking dangers to yield posed by verticillium stem stripe. This sly disease is known to sit in soils for years and though it may infect plants in autumn,will silently damage the plant’s systems throughout the season,only evident through physical symptoms immediately pre-harvest –– meaning it can go undetected,warns Chris.

“OSR growers have been through quite a few challenges in the past two years,including drought and cabbage stem flea beetle –– especially those in East Anglia and the southeast of England ––while others had gone away from the crop altogether and therefore may have forgotten about the silent killer that’s verticillium,”he says.

The proof of the pudding is always in the eating.That’s one of the reasons why Agrii puts varieties through their paces to get

for three or four years and both Turing and Murray coped with it.”

Managing genetics

One thing NPZ/LSPB has noticed in its breeding programme is that a good verticillium resistance also prevents pod shattering, notes LSPB’s Chris Guest. Although this is anecdotal, he comments that despite LSPB’s hybrids currently not having the pod shatter resistance gene, they still perform very well under field conditions due to their healthy condition throughout the growing season, particularly in the latter stages.

But while breeders continue to look for more advanced solutions to the disease, the advice is to spread risk, says Chris. “It’s about managing the genetics that are on offer and not over-utilising or relying on a specific variety. We’ve seen the OSR area pick back up for the coming harvest and I feel it’ll go up again next year, so consider verticillium resistance as a selecting factor for the autumn.”

Being aware of the disease’s presence means growers can plan for it, adds Craig. “If it’s in your soils, you ought to consider growing varieties that are more resistant.” NPZ/LSPB is now trying to combine verticillium resistance with other disease resistances, says Christian. “In Turing and Murray, this is already combined with light leaf spot resistance. Now we would like to add TuYV and/or clubroot resistance as well, but due to the quantitative nature of the verticillium resistance, it's very hard.

“Even with the development of gene editing and CRISPR-Cas9, you need to identify a major resistance gene first. As long as it hasn't been found we have to keep working on a broad basis and continue with our classical breeding efforts,” he adds. ■

an insider’s view.

David Leaper’s assessment of Agrii’s trial sites last year highlights the advances in resistance to the disease in LSPB varieties.“Turing,Vegas and Flemming demonstrated very clean stem health towards the end of the season with low levels of verticillium symptoms.This was in contrast to other hybrids,which,although still high yielding,had high levels of symptoms,”he explains.

He also suggests that growers shouldn’t be put off by the lack of turnip yellow virus resistance in the LSPB varieties.“They generally have good disease resistance and are yielding at the top end. So even though they don’t have the full traits package,they’re still bringing a great deal to the party.”

Prior to verticillium being formally identified in the UK,its symptoms tended to be masked by other diseases,adds David.“Now,I find one pair of eyes late in the season can get consistent

information on it.And while some argue that opening up rotations help, it still tends to feature later in the season,especially if there’s stress on the plants from things such as drought conditions.”

CPM would like to thank LSPB for kindly sponsoring this article,and for providing privileged access to staff and material used to help put the article together.

Innovation

Insight

LSPB has produced several innovative new varieties with good quantitative resistance to verticillium.

In trials,David Leaper says the resistance to verticillium was noticeable in LSPB varieties.

24 crop production magazine februar y 2023 Innovation Insight ▲

Outsmarting the beetle

Cabbage stem flea beetle

It might appear the challenge of cabbage stem flea beetle is insurmountable,but the industry has not sat on its laurels since losing neonicotinoids. CPM gets the scoop on the latest results from NIAB’s csfbSmart project.

By Melanie Jenkins

Growers could well be resigned to the fact that cabbage stem flea beetle is a problem that’s here to stay and that in some years it will cause large losses and in others it won’t. But as part of the csfbSmart initiative,NIAB has been looking at practical ways to keep this most nuisance of pests from damaging oilseed rape crops,driven by farmer led involvement.

And based on stem samples sent to NIAB from growers in 2021, the geographical spread of CSFB has widened across the country, with the pest now found north of Berwick-upon-Tweed and in higher numbers in North Wales than previously witnessed. “It’s not just in the home counties anymore, but has spread much further,” says Colin Peters of NIAB.

One of the big headaches with CSFB is its larvae, which may be found in stems and petioles of plants. Three years ago, a large chunk of the crop was lost after Christmas because of this, says Colin. “This is still causing difficulties now and growers have asked, ‘if I get my crop established, how am I going to help get it to fruition’?.”

During the 2019/20 season, NIAB picked out some differences in adult CSFB preference towards certain OSR varieties in small plot trials, explains Colin. “There appeared to be some favoured movement of adults when they were laying eggs.”

To test this, NIAB looked at three different varieties (based on informed discussion about in field CSFB behaviour) grown as monocrops in 24x24m plots. “We also drilled 80:20 splits of the varieties but at 900 to one another so as to easily pick the different varieties for stem sampling at two Cambridgeshire sites.”

Larval burdens

The varieties used were Aspire, Aurelia and DK Expectation. “Aspire picked up the least stem larvae in both situations, followed by Aurelia and then Expectation. But there was no statistical difference between Aurelia and Expectation at all, and Aspire might only have had the least larvae because it emerges more slowly.

“In the control plots based in Cambridge and Dorset, there was a difference in larval numbers but when we tried to integrate the different varieties into a blend with the aim of using one variety to take the higher burden, there clearly was no difference,” he explains.

“It was a very exciting idea but, unfortunately, when we looked at these varieties there was no difference at all so this won’t be something we will be following up on,” says Colin.

Another investigation NIAB has undertaken has involved looking at longer lasting companion crops which are thought to work by masking OSR crops from CSFB adults looking to lay eggs or feed on young plants through the late autumn and winter period.

It does appear that there’s a reduction in stem larvae where longer lasting companion

crops are grown, says Colin. “This fits with what we’re seeing with the emergence data. We’re looking to sample as many crops as we can this winter that have later lasting companion crops such as vetches, beans, phacelia and are happy to visit any farmers that have such crops to sample and provide information that may help their management moving forwards.”

And diversity of companion crops may play a role in deterring CSFB adults from OSR plants. “We noticed that where a grower had a wide mix of companion crops there

Based on what we have seen so far,volunteers don’t act as a trap crop in any way.

“ ”

Results from the csfbSMART project show that the geographical spread of CSFB has widened across the country.

26 crop production magazine februar y 2023 ▲

was a significant reduction in stem larvae, which we can only assume is due to the crop being masked at the time the adults were flying around looking for it.”

But what has the project learnt about adult movements? In 2021, NIAB used water traps in volunteers next to emerging OSR crops to assess whether these can act as trap crops, which is one of ideas which has seemed promising in previous ADAS research.

Trap cropping

“We hardly saw any CSFB in these traps, so it looks as if the adults are emerging from August through to November and leaving the field,” says Colin. “But we’re well aware that many insects are programmed to leave the site they emerge from to go and populate other areas.”

The 2022 season was unique in that the hot, dry summer and early autumn meant volunteers were only just emerging in September, but again, none of these showed any CSFB damage, adds Colin. “So that rubber stamps it. We do have to be careful as this is only one year’s worth of data, but based on what we have seen so far, volunteers don’t act as a trap crop in any way.”

A further idea NIAB is investigating looks at the concept that the pest may have a

Longer lasting companion crops are thought to mask OSR crops from CSFB adults looking to lay eggs, says Colin Peters.

vulnerable stage in August when pupae are in the soil, and that could be taken advantage of through the use of shallow cultivations. It’s a similar strategy to one being employed to reduce wireworm in arable soils, says Colin.

“We had two farmers carry out different depth cultivations on their farms, with traps placed in both cultivated and uncultivated fields. The first farm’s cultivated fields demonstrated a 68% reduction in CSFB emergence to the end of September,” says Colin. “The pests started to catch up a bit, so by the end of November this dropped to a 63% reduction. This intimates that this window of vulnerability exists.”

At the second farm, which had slightly deeper cultivations, there was a 93.7% reduction in emergence to the end of September, which fell to 90% by the end of November. “These cultivations were done straight after harvest and didn’t affect the emergence of volunteers, so the fields still greened up nicely. We think this is quite exciting and we will hopefully look at this in more detail by taking core samples of soil to understand what’s going on with the larvae.”

The csfbSmart project looked at whether CSFB had a preference towards one OSR variety over another.

To help further its investigations, NIAB requests any growers who still have living companion crops with their OSR to get in touch as it would be interested in taking samples. ■

▲

Arguably,insect pests now provide one of the greatest challenges for crop producers and their agronomists. While other threats, like weeds and fungal pathogens,are becoming harder to control due to loss of crop protection products and resistance, concerns over the impact of insecticides on non-target fauna has hit insecticide availability hard.

As a consequence, it’s become very difficult to bring new products to the market. And that’s before considering the impact of a changing climate, which is making local seasonal risk much harder to predict.

One insect that has become more complicated to manage over recent years is wheat bulb fly. Previous control relied on organophosphate insecticides, chlorpyrifos

New tools for post-insecticide era

and dimethoate, which were withdrawn in the mid 2010s.

Chlorpyrifos targeted the larvae after they hatched and before they managed to burrow into cereal seedlings, preventing the dead heart symptoms synonymous with wheat bulb fly attack.

Dimethoate was utilised as a dead heart spray, giving some control of larvae already feeding inside plants, and provided a last line of defence against significant crop damage.

Pest surveillance

The product losses led to DOW AgroScience (now Corteva) withdrawing commercial funding for PestWatch, an ADAS-led initiative which monitored wheat bulb fly egg hatch progress across the country and advised growers when to apply Dursban WG (chlorpyriphos).

AHDB continued to fund an autumn survey –– an ADAS-led initiative running since 1984 –– which identifies annual wheat bulb fly risk using egg extraction from soil samples taken at 30 reference sites. However, the process is both costly and time consuming, says AHDB crop protection scientist Siobhan Hillman.

“Large quantities of soil are processed to get the results and isn’t necessarily representative of a farm’s local risk, given the relatively low number of reference sites,” she says.

To try and improve the information the autumn survey provides, a recent

AHDB-funded research project has explored the potential of mathematical models to help growers manage the pest in the absence of the most effective chemical controls. ▲

29 crop production magazine februar y 2023

Wheat bulb fly is a pest that’s been in slow decline over the past 10 years but, given the right conditions,it can still pack a punch in cereal crops. CPM looks at some new research that will better predict seasonal risk and how to manage it without insecticides.

By Adam Clarke

Steve Ellis explains that entomologists have been working with crop physiologists to tr y and develop a non-chemical WBF control strategy to limit impact on yield.

We’re heading towards a future where we are far less reliant on insecticides.

“ ”

WBF eggs hatch from January to March and burrow into crops,feeding on shoots through March and April.

According to the project’s lead, ADAS entomologist Steve Ellis says it’s hoped that this will lead to more timely and accurate forecasting of WBF risk, allowing cereal growers to adapt cereal crop management to minimise damage.

He explains that thinking on wheat bulb fly can be divided into two strands –– one which looks at conventionally timed sowings (September to October) when growers have no chemical options to control WBF.

The second is late sowings (November onwards) when growers have the option of using Signal 300 ES (cypermethrin) to protect seedlings from invading larvae at their most vulnerable stage.

“Because most crops will be sown in the conventional window where there’s no chemical intervention, we’ve been working with crop physiologists to try and develop a non-chemical control strategy to limit impact on yield,” says Steve.

So why are physiologists involved? Having successfully helped update the

threshold advice for pollen beetle in oilseed rape, by taking into consideration the amount of flower buds a plant could afford to lose before losing yield, similar logic was applied to the wheat crop.

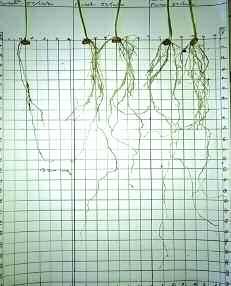

A wheat crop requires about 500 shoots/m2 by GS31 to achieve its full potential. This can be increased to 600 shoots/m2 where a yield of 11t/ha plus is expected. Steve says this leads to the argument that, like oilseed rape and its flowers, there’s a reservoir of excess shoots most wheat crops can afford to sacrifice to wheat bulb fly before losing yield. Most conventionally timed drillings often have 1000 shoots/m2 at GS31, he points out.

Management information

“When we started to investigate this, we realised that we needed to be able to model or predict the number of shoots a crop will have at GS31, based on seed rate and sowing date. What the physiologists have done is produce that model, and it provides extremely valuable information to use in terms of managing wheat bulb fly.”

Knowing how many shoots a crop will produce and how many WBF eggs/m2 there are in the soil allows an estimate of how many shoots a crop is likely to lose, he explains.

Steve highlights that this calculation must also consider established knowledge about WBF biology, including the fact that not all eggs hatch –– literature suggests just 46% produce a potentially damaging larva.

Furthermore, it’s known that each larva has four instars and get bigger and hungrier each time it moults. As the larva feeds and moves through those growth stages, it has the potential to eat up to four shoots.

“So, if we multiply the number of viable eggs by four, that will give the number of shoots that could potentially be lost in each crop. You can then subtract that from the potential number of shoots you expect to achieve from your sowing date and seed rate.

“Then you can start to think about how you can manipulate the seed rate and/or sowing date to produce more shoots if the damage takes you below the optimum 500-600 shoots/m2 threshold,” explains Steve.

“We’re heading towards a future where we are far less reliant on insecticides because the ones that are available are likely to become more expensive and fewer in number. We need to start thinking of other ways to manage these pests,” notes Steve.

On top of the modelling work, the project has also looked at how technology and modelling can make the soil egg count work more efficient. Currently, the process involves the ADAS team roaming around the 30 reference sites with a golf hole borer, taking 20 soil cores over a 4ha area. With each core weighing about the same as a bag of sugar, it means there are huge

Autumn 2022 survey results