14 minute read

Juvenile Interrogation Law for Psychologists: The New Jersey Case Law

from NJ Psychologist Winter 2021

by NJPA

By, Matthew B. Johnson, PhD, Erica R. Young, & Kimberly Echevarria

“A thirteen-year-old cannot be expected to assert his right to remain silent when the detective is repeatedly exhorting that he has to speak.” New Jersey Supreme Court Justice, Barry T. Albin’s dissent in State ex rel. A.W. (2012).

Advertisement

The interrogation of juveniles has been a central issue in forensic psychology for several decades (Grisso, 1981). There is also renewed interest related to the popular film coverage of the Central Park Five exonerees (DuVernay, 2019; Burns, 2012) and the controversial conviction of Brendan Dassey from Wisconsin (Padilla, 2019; Ricciardo & Demos, 2015). In many ways, the US Supreme Court invited psychological research and consultation with the remark, “… the modern practice of in-custody interrogation is psychologically rather than physically oriented” (Miranda v Arizona, 1966, p. 708). Grisso’s early research underlined the vulnerability of youth during criminal interrogation and introduced empirical assessment methods (Grisso, 1998). The legal framework governing the interrogation of juveniles is largely state specific. Johnson (2002) reviewed the New Jersey juvenile ‘Miranda’ case law and identified factors the state high courts recognized as relevant in determining the admissibility of incriminating statements elicited from juveniles. The review provided guidance to psychologists conducting forensic examinations (Johnson & Hunt, 2000). The review also advocated the mandatory recording of all custodial questioning (Johnson, 2005; Johnson, 2000) that was subsequently adopted by the New Jersey Supreme Court and Legislature (Rabner, 2006).

Juvenile Miranda Case Law in New Jersey, 1966 - 2001

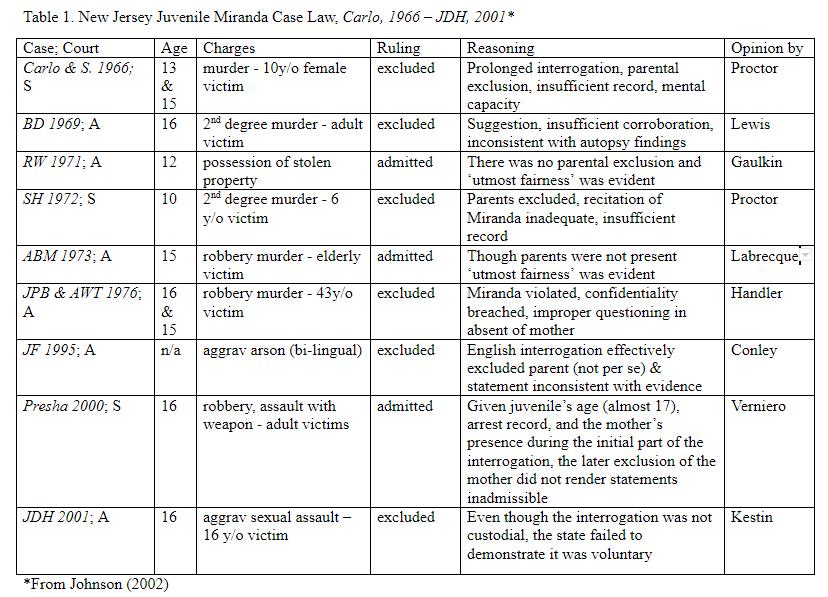

Johnson (2002) cited nine New Jersey high court rulings on juvenile interrogation since the right-to-counsel and privilege against self- incrimination were extended to juvenile suspects (In Re Gault, 1966). In these opinions, the courts sought to balance the need to maintain adequate due process protections for juvenile suspects while also protecting the public from juvenile offending. The nine decisions are summarized in Table 1.

The ‘Reasoning’ Column in Table 1, identifies various factors the courts have noted in ruling incriminating statements (‘confessions’) were not admissible (the juvenile’s age, prolonged interrogation, parental exclusion, insufficient documentation, mental limitations, evidence of suggestion, insufficient corroboration, inadequate Mirandizing, parental presence during initial Mirandizing, fairness, and voluntariness). Psychological examination can be critical in the assessment of these factors. Psychologists have unique skills and knowledge (clinical interviewing, testing and assessment, knowledge of child and adolescent development, and research informed literature regarding Miranda comprehension and risks of false confession) that can be applied to consultation and testimony regarding juvenile interrogation.

It is essential to recognize how courts typically weigh and consider these factors. The US Supreme Court (Fare v. Michael C., 1979) and the New Jersey Supreme Court (State v. Presha, 2000) hold the admissibility of statements from custodial interrogation is determined through analysis of the ‘totality of circumstances’ (TOC). In this regard, psychologists (Kassin, Drizin, Grisso, Gudjonsson et al, 2010) have differentiated situational/ contextual and dispositional/personal factors associated with increased risk of unreliable ‘confession’ evidence (see Table 2). With the ‘TOC’ approach to analysis, the existence of any one or two (or more) of the factors does not determine the ruling on admissibility. Rather, the court weighs the various factors. For instance, a court might rule a prolonged or deceptive interrogation would render the incriminating statement from a 14-year-old to be inadmissible while the same methods used to interrogate a 17-year-old juvenile suspect, with a history of multiple arrests, may be acceptable [1].

Table 2. Situational and Dispositional Risks During Custodial Interrogation*

Categories Examples

Situational/ contextual factors

Isolation, prolonged interrogation, false incriminating evidence, minimization (themes) Dispositional/personal factors Youth and immaturity, cognitive limitations, mental illness, suggestibility, compliance

*From Kassin et al, 2010

Comprehensive psychological examination including review of relevant records (discovery, educational, mental health, and medical), interviews with the juvenile and informants (such a parent/guardian), psychological test data, and assessment of possible malingering, are invaluable in presenting to the court a host of factors that warrant consideration in the TOC inquiry (Goldstein & Goldstein, 2010; Rodgers, Sharf, & Henry et al, 2018; Zelle, Romaine, & Goldstein, 2015).

Juvenile Miranda Case Law in New Jersey, 2002 – present

Since the prior review (Johnson, 2002), the New Jersey Appellate and Supreme Courts have published seven additional case law rulings which further elaborate the state specific law regarding the interrogation of juveniles (see Table 3).

As noted above, the state has adopted a rule requiring law enforcement to electronically record the entire custodial interrogation of criminal suspects, juveniles as well as adults. The resultant objective record of interrogations only enhances the understanding of criminal interrogation, the risks encountered for suspects, as well as the risks to the integrity of criminal investigation.

Before review of New Jersey high court rulings since 2002, a comment is warranted on State v. Presha (2000) that is frequently cited as the guiding New Jersey State Supreme Court decision on juvenile interrogation (State in the Interest of AA, 2018; State ex rel. AW, 2012; State in the Interest of AS, 2010). Among other things, the Presha ruling delineated a ‘bright line rule,’ “When the juvenile is under the age of fourteen, the adult’s absence will render the young offender’s statement inadmissible as a matter of law--unless the adult is truly unavailable [or unwilling to be present] (Presha p. 13).” In such cases, the questioning should be conducted with, “utmost fairness and in accordance with the highest standards of due process and fundamental fairness.” (p. 12). While this assertion in Presha affirms special protection to juvenile suspects below age 14, the only prior case where such statements were ruled admissible by the high courts was State in the Interest of RW (1971), where it was the juvenile who undermined the efforts of the police to involve the parent (Johnson, 2002).

In State in the interest of JDH (2002), the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed the appellate ruling that had excluded incriminating statements by a 16-year-old suspect who had been surreptitiously recorded by a sexual assault complainant under the direction of a prosecutor. The court held the state did not have to prove the statement was voluntary because the juvenile was not in custody. In State in the interest of QN (2004) a 12-year-old juvenile was charged with the sexual assault of “young girls.” Considering the TOC, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled the juvenile’s incriminating statements were admissible even though he was under age 14 and the parent was absent during part of the interrogation. The court determined the parental absence was voluntary, not the result of exclusion by the interrogating officer, and the interrogation proceeded with ‘utmost fairness.’ In the published dissent, Justice Wallace (joined by Justice Long) held that because the law enforcement officer initiated the request to question the minor alone, and the minor did not have an opportunity for a private consultation with the mother, and the child and mother were not informed that either could refuse to allow the child to be questioned alone, the state had not met it’s burden of proving the interrogation was consistent with the “… highest standards of due process…” as required in State v. Presha (2000). In State in the Interest of AS (2009) a New Jersey Appellate Court ruled the incriminating statement of a 14-year-old female, charged with aggravated sexual assault, was inadmissible due to several factors (the suspect’s age, deficit reading level, lack of prior exposure to Miranda, and irregularities in the Mirandizing process). In addition, the court noted the juvenile’s (adoptive) mother had an apparent conflict of interest because the victim of the reported assault was her four-year-old biological grandson. The adoptive mother was markedly accusatory toward the juvenile during the police interrogation and the defense argued the record verified the minor was “badgered to confess by the mother” (p. 8) [2]. Interestingly, the court noted the juvenile testified at the suppression hearing that she sought to exercise her right to silence, “[w]hen I would remain silent they kept on asking me the same questions over and over again for me to answer. They never said that I had to say, no, I don’t want to talk no more. It says remain silent and that’s what I had did.” (p. 7). The appellate court ruled the incriminating statements were not admissible, but the juvenile was still adjudicated delinquent based on other evidence, principally the testimony of the four-year-old. Also, the appellate court stated that in future cases, where the parent/ guardian has a conflict with respect to the juvenile suspect and the identified offense victim, an attorney should be appointed to represent the juvenile. As a result, the prosecution appealed to the State Supreme Court and the defense cross-appealed. On appeal, the New Jersey Supreme Court (State in the Interest of AS, 2010) affirmed the exclusion of the juvenile’s incriminating statement. In addition, the court reversed the delinquency adjudication and remanded the case for a new trial, noting the admission of the incriminating statements at trial was not harmless. The court stated it was unlikely that even a highly capable judge can compartmentalize evidence of such magnitude as the involuntary incriminating statements that were presented at trial (see Wallace & Kassin, 2012). The Supreme Court also ruled that where a parent had conflicting loyalties, the police can secure another adult to act as advisor during interrogation rather than requiring the appointment of a lawyer.

In State ex rel. P.M.P. (2009), the prosecutor’s office filed a delinquency complaint and obtained an arrest warrant naming 20-year-old PMP. It was alleged PMP committed sexual acts when he was a juvenile. However, the complainant was unsure whether the acts occurred during the summer of 2001 or 2002. The following day PMP was arrested, mirandized, and reportedly admitted wrongdoing. PMP filed a motion to suppress the statements, arguing the filing of the delinquency complaint was the equivalent

of an indictment and thus his right to counsel was automatically operative. The New Jersey State Supreme Court held PMP could only waive his right to counsel in the presence of, and after consultation with, counsel (N.J.S.A. 2A:4A-39, 2014), and thus the statement was inadmissible. State ex rel. AW (2012) resulted in a complex record involving multiple considerations such as the Presha ‘bright line’ rule regarding juveniles under age 14, bilingual interrogation, parental exclusion, fidelity to Miranda, Reid interrogation methods, and related social science research. It was alleged 13-year-old, AW committed sexual acts upon a five-year-old victim (his cousin). There was no medical evidence of abuse, but none would result from the acts alleged. Writing for the majority, Supreme Court Justice Hoens summarized the disputes as involving two basic considerations; a) whether the interrogating officer impermissibly suggested the parent leave the interrogation where he was supporting his son, and b) whether the interrogation techniques were unduly coercive and inappropriate for a juvenile. The majority determined the juvenile’s confession “was made knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily” (p. 14), and the questioning was consistent with the “highest standards of fundamental fairness and due process” (p.15), consistent with State v. Presha (2000). It was noted the interrogation was brief (45 minutes), conducted by a female detective, in civilian clothing, at a Child Advocacy Center (rather than a precinct). The detective was described as calm and even toned in her voice, and the father agreed to leave the interrogation at his son’s request. The AW case also produced a dissenting opinion by Justice Albin that cited relevant psychological and social science research (such as Kassin et al, 2010; Drizin & Leo, 2004; and the ACLU of New Jersey amicus brief State of New Jersey in the Interest of AW, 2011) related to juvenile interrogation. Albin advanced five points to support his opinion the incriminating statements should be suppressed and the case should be remanded for re-trial. 1) The juvenile’s request his father leave the interrogation was the product of suggestions by the interrogator, and portions of the interrogation occurred in English that effectively excluded the father. 2) The ‘Reid’ method trained interrogator presented apparently false incriminating evidence to the juvenile. 3) The interrogator refused to accept the juvenile’s denials of the allegations. 4) The interrogator minimized the seriousness of the alleged offense, suggesting the juvenile merely made a ‘mistake’ or was ‘experimenting’. 5) And finally, the interrogator provided assurances of leniency if the juvenile confessed, suggesting he would get therapy and not be jailed. Albin held the combination of these factors had the capacity not only to overbear the will of a 13-year-old, but also to induce a false confession. In State in the Interest of AA (2018), Appellate Court Judge Manahan addressed an issue without precedent in New Jersey. A juvenile, AA (age not reported), was adjudicated delinquent for aggravated assault and firearms possession. AA was allegedly among a group of three African-American males who rode their bicycles in unison, while one of them fired a handgun striking two individuals producing nonlife-threatening injuries. Just prior to the shooting, AA had been seen in the vicinity on a bicycle by a police officer who had arrested AA in the past. Available video surveillance was not adequate to confirm identifications. No handgun was recovered. The trial judge admitted into evidence statements AA made to his mother while he was held at the juvenile detention center. That is, a detective testified he informed the mother of the allegations against AA. The mother became emotional, questioned AA, and the juvenile responded, “Because they jumped us last week”. The detective reported he stood 10 – 12 feet away when he heard the exchange. The trial judge reasoned the statements were not the product of police interrogation and thus Miranda warnings were not necessary. The Appellate Court disagreed noting since AA was in custody, and he experienced the “functional equivalent of police interrogation” (p. 9), Miranda warnings were required and thus the statement should have been suppressed. The adjudication was reversed and the case was remanded to the lower court. In addition, the Appellate Court noted the juvenile and parent were not provided a private consultation to which they were entitled to effectively serve the purpose of parental advice and guidance consistent with Presha.

Summary and Discussion:

Review of the recent New Jersey case law reveals several factors the courts have relied upon in determining the admissibility of statements obtained during the interrogation of juveniles. Identified factors include whether the juvenile was in fact in custody, the circumstances of parental absence, the fairness of the interrogation, the juvenile’s age, intelligence, and experience with interrogation, parental support during interrogation, presentation of the Miranda warnings, the impact of improperly admitted incriminating statements, use of language to exclude a parent in a bilingual interrogation, implied leniency, and provision of a private consultation. Psychological assessment skills, coupled with

research informed knowledge of child and adolescent development, can provide the basis for expert witness examination and testimony.

The TOC framework suggests examination should not be limited to delineating deficits such as age or cognitive impairments but must outline the suspect’s vulnerabilities in the context of how the interrogation was conducted (Johnson & Hunt, 2000). For example, as noted by Justice Albin (State ex rel. AW, 2012), how is a 13-year-old to understand his right to silence if he is continually told by the detective he has to speak. Similarly, suggestions or offers of help during interrogation may nullify the Miranda warning that statements will be used against the suspect in court. Psychologists can also contribute by conducting research to further explore processes in juvenile interrogation. For instance, does research support the assertion that a 12 or 13-year-old can make a knowing, intelligent, and voluntary surrender of constitutional rights, as the courts asserted in QN (2004) and AW (2012)? Might there be a better way to frame and evaluate the circumstances of such a youthful suspect? Another question, is whether parental presence is sufficient or effective protection for juveniles during custodial interrogation (see Cleary & Warner, 2017; Woolard et al 2008)? The case law review suggests while some parents are capable of advising youths on the exercise of their rights, other parents (for any number of reasons) are punitive and align with police interrogators. In some circumstances, parents may be simply uninformed and incapable of providing effective assistance. It is relevant to note that a leading interrogation training manual instructs officers to discourage the parent from talking and confine their role to that of an observer (Inbau et al, 2013). Also, a related question, apparent in the above review is, what are the elements of a meaningful private consultation between the juvenile and the parent in the context of juvenile interrogation?

Notes

1. Even where the incriminating statement is ruled admissible, psychological testimony challenging the reliability of the statement can be presented at trial (Crane v. Kentucky, 1986). 2. AS was the first New Jersey juvenile Miranda case law decision to be informed by an electronic recording of the full interrogation.

About the Authors

Matthew Barry Johnson, PhD is an associate professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice-CUNY. He recently authored ‘Wrongful Conviction in Sexual Assault: Stranger Rape, Acquaintance Rape, and Intra-familial Child Sexual Assault’ for Oxford University Press. Erica R. Young is a graduate student in Forensic Psychology at Kean University. Her interests are in interrogation policy and research regarding Miranda rights. Kimberly Echevarria is a senior undergraduate student majoring in forensic psychology and minoring in law at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY). Her research interests include juvenile interrogation, as well as factors involved in wrongful convictions (i.e. false confessions, eyewitness misidentification, official misconduct, etc).

References

Furnished Upon Request