18 minute read

A Perspective on the Coronavirus Pandemic in Correctional Facilities: Recommendations for Mental Health Practitioners

from NJ Psychologist Winter 2021

by NJPA

By, Sharron Spriggs, Caitlin E. Krause, and Georgia M. Winters, PhD Department of Psychology and Counseling, Fairleigh Dickinson University

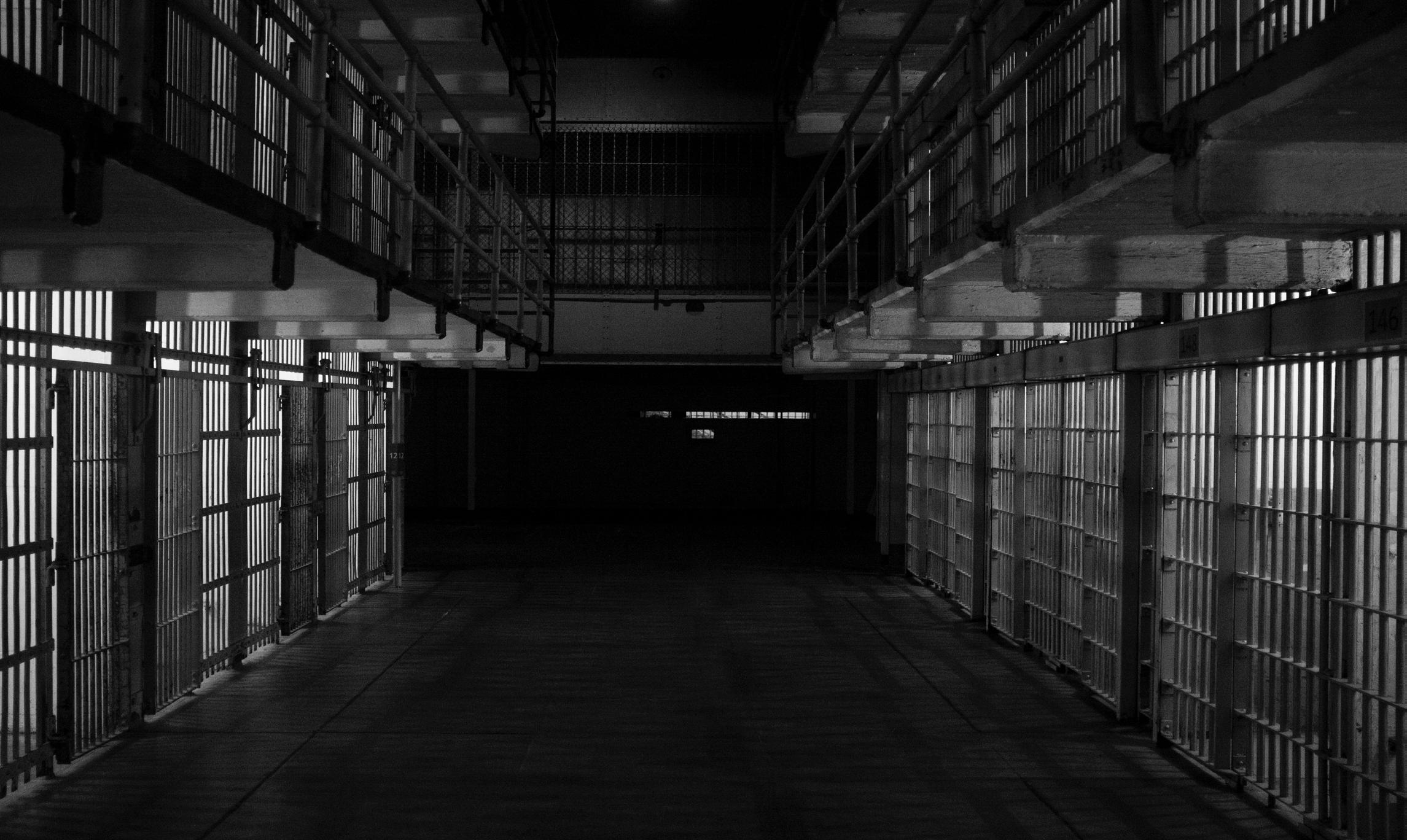

Since the start of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, it is estimated that over 14 million individuals have tested positive for COVID-19, and over 600,000 individuals have died across 213 countries and territories (Worldometer, 2020). As a result, COVID-19 has been deemed a “once-in-a-century pandemic” (Gates, 2020). Government officials around the world have implemented numerous regulations to slow the spread of COVID-19, such as stay-at-home orders, school closures, and social distancing mandates (Harvard Medical School, 2020; Wamsley, 2020). For correctional settings, the spread of the coronavirus presents unique challenges due to a constellation of factors, including: 1) the overcrowding of prisons and jails, 2) the lack of resources at correctional facilities to decrease community spread, and 3) many inmates have a myriad of pre-existing health conditions that leave them especially vulnerable (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020; Vance, 2020). Ultimately, these unique conditions have produced unprecedented challenges for health care providers, including psychologists, working in jails and prisons. Therefore, the present article aims to provide an overview of the impact of COVID-19 on correctional facilities, followed by recommendations for psychologists working in these settings.

Advertisement

The Impact of the Coronavirus on Correctional Populations

According to the Marshall Project (2020), over 64,000 prisoners in the US have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and over 650 prisoners have died. In fact, correctional facilities represent 7 out of the 10 largest outbreaks across the US based on the percentage of the population infected (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). For example, 15.7% of COVID-19 cases in Illinois can be traced back to the Cook County Jail (Health Affairs, 2020). COVID-19 is disproportionately impacting incarcerated individuals compared to the general public, with the known infection rate for COVID-19 in the prison population being 2.5 times higher than that of the general population (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). In April 2020, there was an estimate of 696 positive coronavirus cases per 100,000 prisoners, compared to 250 positive cases per 100,000 people in the general population (Park et al., 2020). Moreover, data from June 2020 indicated that the number of positive cases in correctional facilities has continued to increase even as the number of positive cases decreases in the general population. While it is possible this could be attributed to increased testing among prison populations, especially amongst the hardest-hit states (e.g., Ohio, Michigan, Tennessee, and Texas), prisoners are nonetheless facing increased risk for infection (The Marshall Project, 2020). Of those states that do mass testing (e.g., Ohio), up to 85% of the prisoners tested positive for COVID-19 (Sawyer, 2020). As a result, media outlets and health advisors have deemed prisons as “clusters” of the coronavirus outbreak, a phrase that has also been attributed to nursing homes and food processing plants, two other highrisk settings (The New York Times, 2020).

Factors that Increase Risk in Correctional Settings

As described above, with the emergence of COVID-19, issues were raised about prisons being incubators of infectious diseases, highlighting that “prison health is public health” (Kinner et al., 2020). The World Health Organization’s (WHO; 2020) guidelines on responding to COVID-19 in prisons recommended “urgently” addressing risk management, prevention, control, and treatment in such facilities. However, there was no consensus on how to implement such action, leaving correctional facilities vulnerable to outbreaks. Several factors may increase prisoners’ risk of contracting the coronavirus, including (1) overcrowding, (2) limited access to resources (e.g., hand soap and hand sanitizer), and (3) the vulnerable prison population. Overcrowding has been described as “one of the key contributors to poor prison conditions” (Penal Reform International, 2020), which is particularly relevant during the coronavirus pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2020a) recommends keeping six feet between individuals (i.e., social distancing) to prevent the spread of the coronavirus; however, correctional facilities may not be able to appropriately implement these recommendations. In the US, half of the states and federal prisons have met or exceeded their number of available beds, meaning that they are at capacity or over-capacity (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). In overcrowded prisons, beds may be spaced as close as three feet apart (Kajstura & Landon, 2020), and prisoners can be confined to their shared cells for up to 22 hours a day that could result in near constant exposure to the coronavirus (Eisler et al., 2020). Due to these practices, prisoners are estimated to live in closer-contact conditions than even those on cruise ships (Kajstura & Landon, 2020). The number of prisoners living in close contact with each other makes it difficult to clean surfaces and lavatories between usages, which is especially concerning considering that many individuals infected with COVID-19 are asymptomatic and may be unknowingly spreading the coronavirus to other prisoners (Edwards, 2020). The close living conditions also make it hard to fully separate symptomatic individuals from healthy individuals. Ultimately, overcrowding in prisons results in an inability to social distance, properly sanitize, and separate those that test positive for COVID-19 from those who are healthy. In the national race to procure materials to combat the coronavirus, prisons are often left without proper resources to protect the prisoners and staff. For example, prisons have struggled to get enough test kits for inmates, resulting in only those showing symptoms being tested (Eisler et al., 2020). However, as noted above, there may be asymptomatic individuals among the prisoners who can spread the coronavirus to other prisoners undetected. This is why some states have made an effort to test every inmate to detect the spread of the coronavirus (Aspinwall & Neff, 2020), although this process has not been widely implemented. In addition to the shortage of tests, prisons struggle to get personalprotective equipment, such as N-95 or surgical masks, for their staff and inmates (Eisler et al., 2020). Other preventative measures, such as hand washing and using hand sanitizer, are difficult to implement in prisons. Most prisons have banned prisoners from having hand sanitizer due to its alcohol content, though some have rescinded that ban due to the

pandemic (Tolan, 2020). Another concern is that prisons have finite resources for respiratory support, such as oxygen (Widra & Wagner, 2020). If the prison exhausts its supply of oxygen, they need to transfer the affected prisoner to the hospital, a procedure that could jeopardize the prisoner’s medical condition and potentially expose others to the coronavirus. Indeed, the lack of sanitization and healthcare equipment are unique factors that contribute to exceptional rise and spread of COVID-19 in prison settings. The population in prisons tend to be older, male, and people in poorer health, all factors that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19 (Montoya-Barthelemy et al., 2020; Nowotny et al., 2017; Williams, 2012). Due to various criminal legislation enforcing harsher punishments (e.g., the “three-strikes law” implements a mandatory life sentence for an individual who has been convicted of a felony three times; Caulkins, 2001), prisoners are receiving longer sentences, resulting in prisoners older than 55 comprising the majority of prison population (Williams, 2012). Indeed, the percentage of people in state prisons that are aged 55 or older has more than tripled from 2000 to 2016 (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). Given that research has shown that the coronavirus is more lethal for those over the age of 55, with the risk of death increasing with age, these elder prisoners represent a vulnerable group (CDC, 2020b). Research also indicates that men are more likely to have complications due to COVID-19 and die from it compared to women (Jin et al., 2020). The Federal Bureau of Prisons (2020) reports that 93.2% of incarcerated individuals are male, resulting in a majority of prisoners falling in the high-risk category. Furthermore, the CDC (2020a) warns that those with underlying health conditions, such as diabetes, heart problems, and asthma have a higher risk of severe complications if they contract COVID-19. Prisoners have worse health than those in the general population; specifically, there is a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, asthma, kidney problems, and stroke amongst incarcerated individuals (Nowotny et al., 2017). These health problems may stem from factors external to the prison, such as poverty and genetics, but also the prison environment, such as limited ability to exercise and nutritional deficits (Equal Justice Initiative, 2020). The vulnerable prison population, combined with overcrowding and inadequate resources, places prisons in high risk categories for the spread of COVID-19.

Psychological Implications of the Coronavirus

The American Psychological Association (APA; 2020c) named the coronavirus pandemic a psychological crisis, given the associated social isolation, changes in daily activities, job loss, financial stress, and grief. These mental health concerns can be prevalent for both inmates and correctional psychologists alike. Even before the pandemic, research has consistently shown that prisoners have higher rates of psychiatric disorders in comparison to the general public. In fact, in some states there are more people with severe mental illness in prisons than psychiatric hospitals. Suicide and self-harm are also more common in prisoners than in the general community when compared to persons of similar age and gender (Torrey et al., 2010). The risk of suicide in inmates is approximately 50% more likely for males and 60% more likely for females when compared to the general population. Environmental factors, including overcrowding, close quarters, and periods of isolation (i.e., solitary confinement) further exacerbate these poor mental health outcomes. Then, with the added stress of this mysterious immunocompromising virus that requires isolation (i.e., via social distancing), it is expected that prisoners are suffering from immense stress, depression, fear, and other psychiatric issues (Montoya-Barthelemy et al., 2020; The New York Times, 2020). Psychologists and other mental health workers play a vital role in correctional settings by providing services to treat minor and severe mental illnesses. State and federal government designated psychologists as essential workers (i.e., the only employees allowed to work inperson during the governor’s stay-at-home orders), with the stipulation that psychologists do not have to provide their in-person services and should instead provide services through telehealth (i.e., therapy via zoom or doxy.me; APA, 2020b). During the pandemic, insurance providers, at exceptional rates, covered telehealth for community psychologists and these services have been widely implemented (APA, 2020b). However, this

poses issues for providing psychological treatment to prison populations, as many facilities do not have adequate electronic systems needed for telehealth. Furthermore, even if the facility has adequate electronic systems, prisoners might not have access to personal electronic devices or there may not be enough personal devices available. As such, during the pandemic, when prisoners were in need of mental health treatment more than ever, it is expected these psychological services were limited, if not nonexistent. The expected high rates of mental distress in correction settings, combined with restrictions on available services, poses unique challenges for mental health professionals in jails and prisons. As correctional psychologists continue to utilize telehealth and transition back to in-person therapy upon return to the facilities, it is important to have guidance on ways in which practitioners can best provide services during the coronavirus pandemic.

Recommendations for Mental Health Practitioners in Correctional Settings

Based on the above information, it is clear that mental health practitioners in jails and prisons serve an important role during the pandemic. The following suggestions have been made to increase the wellbeing of both incarcerated prisoners and those who have been, or will be, released because of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as staff working with correctional population.

1) Psychoeducation

Prisoners and correctional staff alike would benefit from opportunities for education about COVID-19 (i.e., the infection rates in the facility; how to prevent spread) and ways of coping (e.g., involvement in enjoyed activities, relaxation techniques), with the aim of reducing anxiety and improving morale (Larsson et al., 2003). These educational services should be provided to inmates and staff on a regular basis and as any changes occur in the facility and could be administered via written (e.g., pamphlets; handouts) and/or verbal (e.g., community meetings) formats. Ideally, these educational services would provide individuals the opportunity to voice their concerns and ask questions to ensure the respect for human dignity. The use of open forums, that comprise both inmates and correctional staff, could be considered in order to promote an integrated and collaborative response. Mental health practitioners can assist in this endeavor by helping create and disseminate pertinent information, as well as facilitate group discussions on the subject.

2) Assessment for Suicide and Psychiatric Issues

As noted previously, there were concerning rates of suicide in incarcerated settings before the pandemic and thus, screening for suicidality and psychological distress is especially pertinent during this time. Ideally, suicide risk assessments should have been conducted on all inmates upon entering the correctional facility or, if there were limited resources, on those individuals who would likely pose a higher risk (Winters, Greene-Colozzi, & Jeglic, 2017). These assessments typically cover relevant risk (e.g., history of suicidal behavior, medical illness, familial history of suicide, life stressors, hopelessness, psychiatric issues) and protective (e.g., quality social supports, religiosity, reasons for living) factors. During the pandemic, it would be beneficial to utilize targeted suicide risk assessments based on those who fell in the moderate or higher risk categories based on these initial assessments. This updated assessment would include the evaluation of notable changes in clinical presentation or recent suicidal ideation, intent, or presence of a plan, as well as other factors relevant to suicidal risk for that individual. This could be facilitated through the use of a thorough clinical interview based on evidence-based factors, and/ or more standardized screening measures, such as

the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2008) and the Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (Jacobs, 2007). Not only should there be screening for suicide specifically, but there should be increased attention to the development of psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and fear, in incarcerated individuals (Montoya-Barthelemy et al., 2020; The New York Times, 2020). It is recommended that mental health providers screen potentially higherrisk prisoners for mental health symptoms and make appropriate referrals (e.g., psychiatric or psychological treatment) as needed. For example, these targeted assessments could be done based on inmates who have documented psychiatric issues or individuals who have displayed recent changes in their clinical presentation (e.g., social isolation, self-harming behavior, panic attacks). Another potentially vulnerable population at this time Includes the pre-trial defendants being housed in correctional facilities. Most courts closed during the height of the pandemic, with many continuing to remain closed or with limited services (United States Courts, 2020), which means that court dates have been pushed back. This understandably could lead to hopelessness, frustration, and other negative emotions for these pre-trial defendants; therefore, increased attention should be paid to these individuals to ensure they are properly assessed and treated, if needed. Lastly, given that psychological staff is likely limited at this time (either working remotely or reduced contact services), it may be beneficial to provide education for front-line staff (e.g., correctional officers) on signs of suicidality and psychological distress, as well as the proper mental health referral channels. A combined effort to recognize and further assess suicidality and psychological distress is highly recommended during the pandemic.

3) Treatment

In addition to providing psychoeducational information to inmates as described above, some prisoners may also benefit from a more targeted treatment regarding COVID-19 concerns. For example, clinicians could organize and implement mental health groups dedicated to discussing and addressing mental health issues as they relate to the coronavirus pandemic. These groups would likely be beneficial, as supportive-expressive therapy has been shown to help those experiencing collective trauma (Gishoma et al., 2014). These groups should also target coping strategies that can be utilized in reducing psychological distress (Morgan et al., 2006). Given that resources ARE likely limited, especially during the pandemic, the identification and selection of services to higher risk groups will be important. That is, higher-risk inmates (e.g., those with serious and persistent mental illness or suicidality) should be provided opportunities for individual and/or group therapy, as these needs require a higher level of care.

4) Early Release

It should be noted that in order to combat the spread of COVID-19, the federal and state governments have attempted to release offenders early or send them to home confinement (Simpson & Butler, 2020). However, there are concerns that those who are released are spreading COVID-19 to the community and, most applicable to mental health professionals, that the prisoners might not be prepared to reintegrate into the community (Westervelt, 2020). To address reintegration, prisoners should be offered pre-release services, such as psychoeducation or therapy, regarding what to expect upon release, how to cope with the barriers and challenges of release, and what services are available in the community. Likewise, prisoners who will be released during this time should be given information regarding the current rates of positive cases in their districts and legislative rules in that area. Providing additional attention and care to those who are being release early can help ensure smoother transitions back to the community.

5) Psychologist Competence

The APA, consistent with ethical guidelines, provided recommendations during the COVID-19 crisis to ensure that psychologists are remaining competent. These recommendations included: competence in telemedicine (i.e., education on rules and regulations regarding HIPAA compliance) before beginning to see patients remotely; boundary setting (i.e., maintaining professionalism in the online setting); and confidentiality (i.e., recommending sessions be conducted in private settings, sending information via secure systems). The APA’s website provides numerous resources related to maintaining ethical and effective practices during the pandemic that all psychologists should become familiar with (APA, 2020a)

6) Psychologist Self-Care

It is important that psychologists practice self-care to avoid burn-out and other issues experienced by essential workers during the COVID-19 crisis, especially those in high risk areas such as

correctional facilities (Clay, 2020). Health care workers report growing concerns about personal safety and lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), transmitting the virus to family and friends, and higher burnout rates (Sasangohar, et al., 2020). It has been noted that mental health professionals may develop anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during these stressful times (Nurse & Ormsby, 2003). As such, the APA has stressed that it is more important now than ever to engage in self-care (Clay, 2020). APA has provided suggestions such as creating a standard daily routine, maintaining health (e.g., healthy eating, exercise, adequate sleep), facilitating socially distanced activities with friends or family, and engaging in mindfulness or relaxation techniques. Psychologists should all work towards identifying and implementing an individualized self-care routine during the pandemic to maintain professional competence and enhance their psychological well-being.

7) Facility Safety Precautions

For treatment providers and evaluators seeing inmates in person, proper safety precautions should be utilized. Treatment rooms should develop safety precautions for groups and individual therapy, such as spaced seating, protective face covering, and other recommended precautions (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2020). Typically, incarcerated individuals are not allowed access to technology; however, during the pandemic, many mental health services were moved from in-person to telecommunication. Given that the use of personal technology devices is prohibited at most correctional facilities, there is an added barrier to inmates receiving psychiatric treatment. Thus, it is recommended that psychologists work with their facilities to increase the availability of these types of services to inmates, such as offering video sessions on communal computers in private locations. As psychologists begin to return to work in-person, there can be the continued use of this type of telecommunication for mental health services to protect against spreading should an inmate exhibit symptoms but still require psychological treatment. Similarly, for pre-trial defendants who need to be evaluated for various reasons (e.g., sentencing mitigation, competency to stand trial, criminal responsibility), they should be provided needed electronic services (e.g., video conferencing) or safe meeting spaces (e.g., socially distanced interviewing rooms with protective gear). While largely beyond the scope of this article and the responsibilities of mental health providers, it should be noted that increased attention must be paid to implement proper safety precautions facility-wide. For example, there should be efforts towards checking temperature and inquiring about relevant symptoms before anyone (staff, inmates, and visitors) enters the facility. Additional safety precautions within the facility could include mandatory mask wearing, increased sanitation services (especially in common areas, such as restrooms or cafeterias), and environmental changes (e.g., installing plexiglass in meeting rooms). There could also be efforts to arrange single-celled rooms and separate living pods, and isolative environments for those who are sick or were knowingly exposed. Regarding visitations (for both professional and personal reasons), there should be established safe meeting rooms, as well as increased access to alternate forms of communication (e.g., video conferencing, telephone).

Conclusion

Currently, in the face of the global pandemic, the correctional settings in the US are facing unprecedented challenges. These settings are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 due to overcrowding, lack of resources, and an already existing vulnerable population. As such, attention must be paid to the mental health of inmates in the context of the pandemic, a responsibility that largely falls on mental health practitioners in correctional settings who provide necessary psychological screening and treatment. Mental health workers in correction facilities can make an important impact through providing prisoner and staff education, increasing assessment and treatment efforts for psychological distress and suicidality, maintaining competence and self-care, and adhering to safety precautions in facilities.

References Furnished Upon Request About the Authors

Sharron Spriggs is a third year doctoral student at Fairleigh Dickinson University studying clinical psychology. Sharron’s interests include public safety assessment. Her dissertation is on investigating the influence of viewing police brutality videos on social media and perceptions of police officers. Caitlin E. Krause is currently a graduate student in Fairleigh Dickinson University’s Forensic Psychology MA program. Her research interests include paraphilic disorders, sexual trauma, and online sexual behavior. Georgia M. Winters, PhD, is an assistant professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University’s School of Psychology and Counseling. Her research focuses on sexual grooming, paraphilias, and sexual violence prevention.