Time Is A Construct

Time is a Construct 34 East 67th Street, Floor 3, New York, NY 10065 Sanjay@kapoors.com | info@kapoors.com kapoors.com | +1.212.888.2257

Published by: Kapoor Assets, Inc.

Printed in New York, New York

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in any part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of Kapoor Assets, Inc.

Photography by: Marcin Muchalski

Design and layout by: ADM Advertising

Text by: Danielle Deluty, Uttara Nanavati

Edited by: Danielle Deluty, Uttara Nanavati

Catalog production: Henry Houston

Cover illustration: Bharany Ramayana

Foreword

We’ve had the privilege of witnessing the art world regain its momentum over the past year. The enthusiastic response we received during Asia Week New York in Spring 2023 transcended expectations, and is a testimony to the endurance of art collectors and connoisseurs alike. This compendium is an ode to the spirit of art appreciation and collection that the Kapoor family endeavors to keep alive. I would like to extend my gratitude to my team at Kapoor Galleries who have been dedicated supporters in making this endeavor possible: Danielle Deluty & Uttara Nanavati. Lastly I would like to offer my gratitude to all of our friends, clients, partners, and those of you in between. I invite you all to engage with our catalog for 2024, a token of dedication to our four-decade old legacy and a promise to keep the continuum intact.

Sanjay Kapoor 2.29.2024

Introduction

Time is a Construct

Art serves as a compass for our collective consciousness, guiding humanity across the vast dimensions of time and space. More than visual expression, art embodies the very essence of culture, punctuating the canvas of existence with strokes of meaning.

This exhibition is an opportunity to pause and reflect on the dynamic but ever constant influence of artistic tradition and lineage across time. Examining Indian miniature painting is a focal point of this introspection. In the world of Indian miniatures, we witness a deliberate repetition of subject matter over centuries. Nuanced artistic evolution is evident across the myriad reinterpretations of familiar characters and other visual elements. The substantive repetition and thematic continuity reveal enduring symbolic resonance of religious tradition. Art doesn’t merely depict the passage of time; it assumes the role of a conductor, steering the passage of time itself. Across diverse cultures, every stroke of artistry and creativity contributes to a narrative unfolding across epochs. In immersive encounters with art the boundaries of time blur, leaving us suspended in the timelessness of human imagination and artistic expression.

Highlights of the exhibition include a fine render from the Bharany Ramayana series, a pair of carved and silvered horses, and a splendid folio from Gita Govinda. The gallery exhibition will also showcase many fine Indian miniature paintings and arms as well as a carefully curated selection of sculptures from India, Nepal, and Tibet. The New York exhibition will be open to the public from the 14th of March through the 22nd. We look forward to sharing this fine assembly of artworks with you!

This catalog is a celebration of the gallery’s forty-plus years of success as a family enterprise, and as such, is dedicated to the memory of Urmil Kapoor (1941-2018). Together with Ramesh Kapoor, she helped bring the field of Indian and Himalayan art to where it is today. After India’s partition in 1947, Ramesh left Pakistan along with his parents and migrated from Lahore to Jalandhar, India. There, the government allocated his father an empty store where he could establish his own business. After a thrift merchant offered him an entire private library, Ramesh’s father started a rental library, catering to Indian refugees whose displacement left them with ample time to read. This led to the acquisition of illustrated books and manuscripts, which helped propel the Kapoor family into the field of the fine art of Indian miniature painting. When Ramesh finished college in 1958 and joined his father in business, the two worked together to establish relationships with museums and universities, supplying these institutions with coveted masterworks. Ramesh and Urmil married in 1967, and witnessing an increasing European and American interest in Indian Art, they immigrated to the United States and established Kapoor Galleries Inc. in New York City in 1975. Since establishment, Kapoor Galleries Inc. has played an instrumental role in educating the public about the ancient and classical fine arts of India and the Himalayas while encouraging interest amongst both collectors and institutions. Ramesh Kapoor has guided some of the most significant public and private collections of the 20th century, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Diego Museum of Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Norton Simon Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Detroit Institute of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and Ball State Museum. We would also like to take this opportunity to extend our deepest gratitude to those who have lent their knowledge and support for this endeavor: Ramesh & Urmil Kapoor, Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, Dr. Daniel Ehnbom, Dr. Gursharan Sidhu, Dr. Gautama Vajracharya, Mitche Kunzman, Dr. Amin Jaffer, Jeff Watt, Dr. Amy Heller, Bob Del Bonta, Steve Kossak, Dr. Vidya and Jay Dehejia, Dr. Harsha Dehejia, Dr. John Guy, Pujan Gandhi, and Dr. Emma Stein.

Enjoy this catalog, and we look forward to welcoming you to Kapoor Galleries!

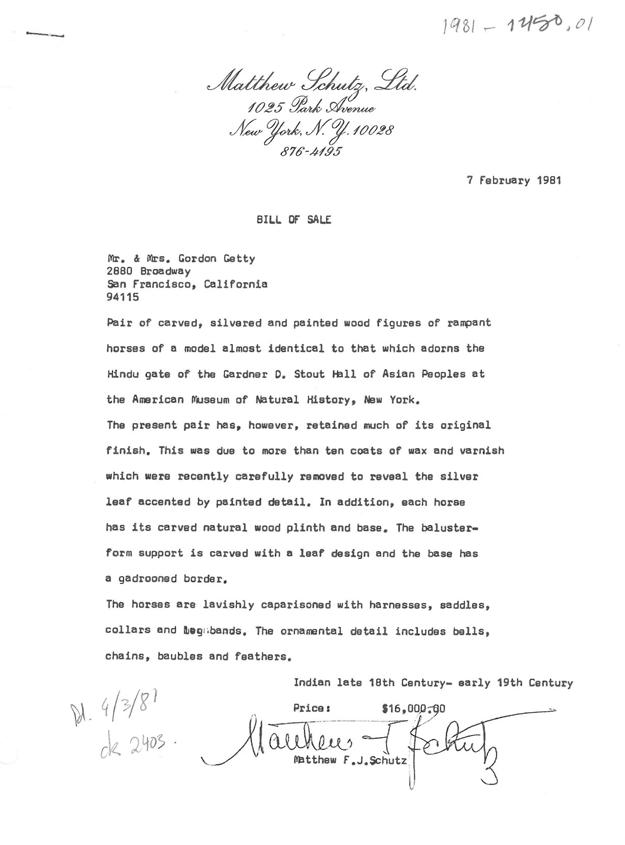

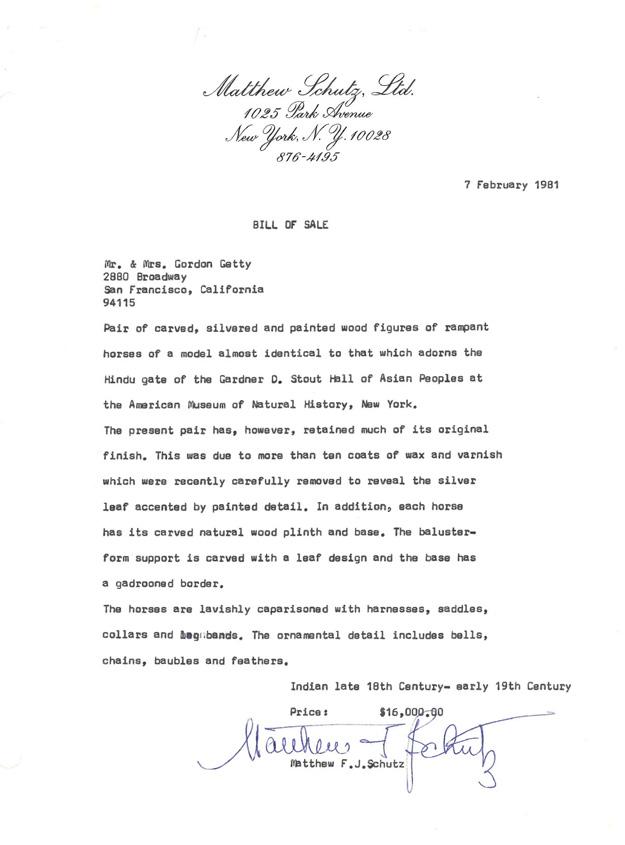

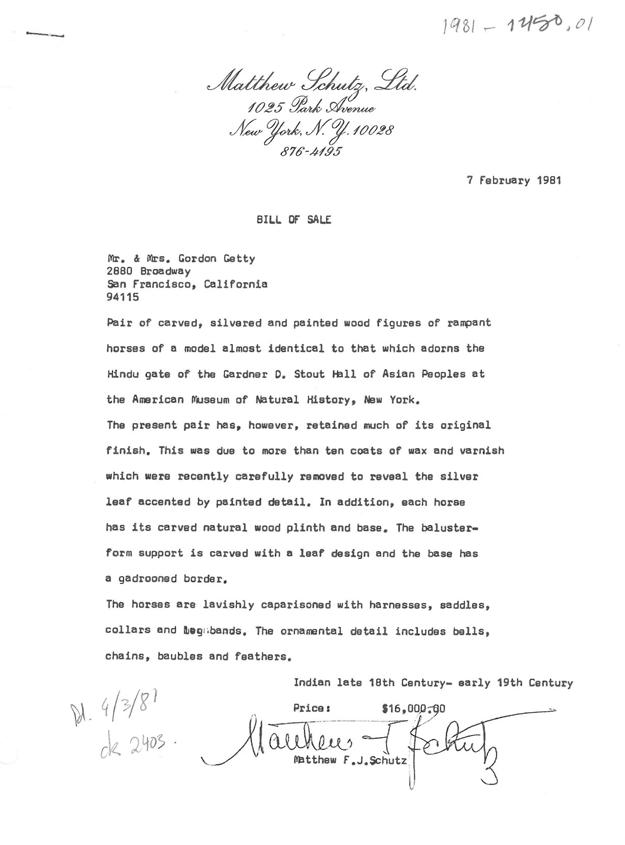

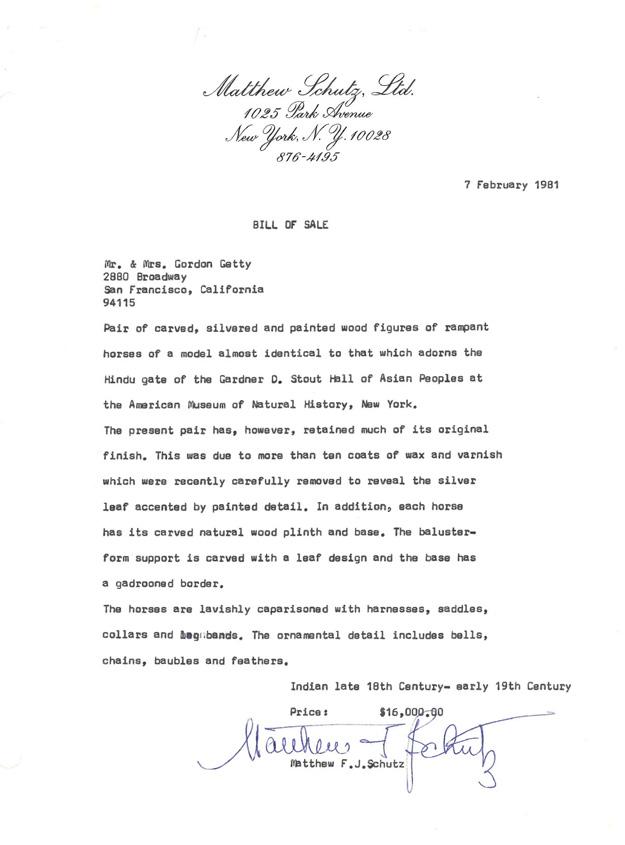

Pair of carved, silvered and painted wood figures of Rampant Horses

India, 19th century Wood, silver, paint 33 ½ in. (85.1 cm.) high.

Provenance:

Acquired from Matthew Schutz, New York, by Ann and Gordon Getty in 1981.

Caparisoned in intricate carvings of jewels and textiles, the present pair of silver horse sculptures are examples of the fine silver craftsmanship in India. The foliate motifs throughout the surface show the traces of low-relief and high-relief silver carving. The lines accentuating the details of the physique of the horses are incised in high-relief, whereas the embellishment through foliate motifs is incised in low-relief. One can also spot motifs like the acanthus leaf motif at the lower limbs of the horse; this speaks for the time period of British Raj in India. In order to meet the demands of their North American and European Clientele, Indian silversmiths created a beautiful fusion of Indian and European design sensibilities. The piece also depicts embellishments of arabesque motifs like flower vines and scrolls.

The winged horse takes the center stage in various Hindu mythic episodes. According to Vastu Shastra (the study of Indian spatial design and architecture) the very archetypal galloping horses symbolize strength, bravery and devotion and are said to charge spaces with positive energy.

A winged horse is the depiction of Devadatta (the horse of Kalki, Vishnu’s tenth incarnation). It is noteworthy that the depiction of Kalki varies in terms of the visual idiom. It is often in the form of a white winged horse or as a warrior on a white horse (both visual idioms are used interchangeably). Refer the following painting (ac.IS.113-1949) from the Victoria and Albert Museum which portrays Kalki with his winged horse.

1

Ganesha

Northeastern India, Pala period, 11th century Gray basalt

26 x 14 1/3 x 3 1/3 in. (66 x 36.3 x 8.4 cm.)

Provenance:

With Moreau-Gobard Gallery, Paris, by the early 1960s. Acquired from the above by Mr. & Mme Michael Rade. Thence by descent.

The elephant-headed god sits in the posture of royal ease holding an axe, a fruit, a radish, and a bowl of sweets. His corpulent belly hangs over the short striped dhoti covering his lower body. A serpent draped across his chest takes the place of the standard sacred cord or yajnopavita worn by Hindu deities while he is otherwise ornamented in jewels. An eight-petaled lotus floats above his enshrined body while his foot rests on another, met by the mouth of his vahana the rat.

This charming image of the widely adored remover of obstacles is carved into a niche with a decorative, stepped architectural element atop resembling an elaborate temple roof. Carved into a dark igneous rock native to the northeastern Indian kingdom of the Pala dynasty, the relief resembles many of those that graced the exteriors of temples therein.

2

Mahakala Shadbhuja

Tibet, 17th century

Bronze with polychrome 6 in. (15 cm.) high.

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item no. 35867.

Provenance:

Toronto Collection, with Spink & Son, London, circa 1995. Christie’s New York, 14 March 2017, lot 209.

Mahakala is the primary Buddhist Dharmapala and is respected in all schools of Tibetan Buddhism. In Sanskrit, Maha translates to “great” and Kala to “time/death.” All names and colors are said to melt into Mahakala, symbolizing his all-encompassing nature and lustrous black skin. He is seen as the absolute reality. Shadbhuja, the six-armed Mahakala, is a favorite amongst the Gelukpa order of Tibetan Buddhism. Shadbhuja is recognized as the fierce, powerful, and wrathful embodiment of the Bodhisattva of compassion Avalokitesvara.

In this elegantly cast piece, attention to fine detail is evident throughout the six-armed form. In the primary left hand is a skull cap (kapala) filled with minced remains of enemies to Dharma. In the primary right hand is a crescent shaped chopper (katrika) or curved knife, which fits to the shape of the skull cap so it can be utilized for making the “mincemeat.” The chopper is a representation of detachment from samsaric existence. Within the secondary right hand lies a damaru, an hourglass-shaped drum which arouses the mentally-clouded from their ignorant state, putting them back onto the path of Dharma. The sound which emanates from the damaru is supposed to be the same as that which manifested all of existence. A rosary of dried skulls adorns the uppermost right hand; this symbolizes the perpetual activity of Mahakala on a cosmic scale, as rings are inherently continuous. The secondary left hand holds a noose, whose function is to lasso those straying from the divine path of Dharma The skin of an elephant is held taut across the back of Mahakala in his upper left hand, symbolizing the ability to overcome delusion.

3

Uma (Parvati)

South India, Tamil Nadu

Chola Period, 11th-12th century Copper alloy

15 x 8 ½ in. (38.1 x 21.5 cm.) high.

Provenance:

The estate of Kelly Brook, acquired in India in the 1950s. Galleria Ethnologica, Forli, Italy, 2011.

Uma appears graceful yet powerful upon a tiered lotus throne. A crown surmounts her discreetly smiling face, modeled with wide eyes, a sharp nose and full lips. Her sacred thread or yajnopavita, guides the eye from her neck down her voluptuous torso and soft belly to her lap, where her beautifully detailed skirt covers her legs to her mid-calf, below which multi-banded anklets and beaded ornaments decorate her down to her feet. She sits in lalitasana, the ‘posture of royal ease,’ with one leg retracted and the other hanging relaxedly off of her throne.

Most images of Parvati in this seated posture belong to a larger group referred to as ‘Somaskanda,’ which describes the divine family constituted by Shiva, Parvati and Skanda. The present figure of Parvati, or ‘Uma’ in the native language of Tamil Nadu, was almost certainly part of a larger group of sculptures which served an essential role in a Shaivite temple centuries ago.

“According to Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy, only when he is in the company of his consort Uma does Shiva bestow grace upon an individual soul. A metal image of the god together with Uma and their son Skanda is thus the principal image of such individual grace, and every single temple, wealthy or otherwise possesses a Somaskanda image” (V. Dehejia, The Sensuous and the Sacred: Chola Bronzes of South India, New York, 2002, p.128.). The image is of such great importance that it may be used as a substitute for any godly image needed for Hindu worship. While the present sculpture, like most figures of its size, was commissioned for and essential for temple worship, the group of three portable bronze images were also processional. Such is indicated by the holes fit for poles seen here, which enable worshipers to carry the divine figures into the streets for all to experience darshan—to meet the gaze of the divine.

There are instances in which bronze Somaskanda images were cast as a whole as well as instances in which they have been cast separately, while intended to be experienced together. One instance of a separatelycast Somaskanda group, such as that from which the present originates, can be found at the Puran Vitankar Temple in Tirumangalakudi, dated circa-1100 by Dehejia (see ibid, p.128, fig. 1). The present figure of Uma, however, differs from this one stylistically.

The eleventh or twelfth century date for the present figure is supported by the crown style, which follows that of Parvati’s in a well known group depicting the marriage of Shiva and Parvati from the Tiruvenkadu temple, circa 1012, now in the Tanjore Art Gallery (see V. Dehejia, Art of the Imperial Cholas, New York, 1990, p. 72, fig. 55). The three tiers of the conical crown and the central ornamented petal, as well as the simple layered necklaces and arm bands framing her buoyant breasts with articulated nipples, however, more closely matches that of a Somaskanda image of Parvati at the Shiva Temple in Paundarikapuram attributed to the late twelfth century (see V. Dehejia, The Sensuous and the Sacred: Chola Bronzes of South India, New York, 2002, p. 43, fig. 22). Moreover, the absence of the three distinct lines above Uma’s abdomen (trivali tarangini), a later Chola convention, supports the early dating of this bronze.

4

A bronze figure of Bhu-Devi, consort of Vishnu

South India, 18th century Bronze

12 1/5 in. (31 cm.) high.

Provenance:

Private Italian collection, given to the owner’s father by Giuseppe Tucci in the 1940s.

One of the consorts of Vishnu is Bhu-devi, the EarthGoddess. When Vishnu incarnated on Earth as Varaha, the anthropomorphic boar, he rescued Bhu-Devi from the deep ocean where she was in the clutches of the demon Hirankshya. It is after this episode that Varaha is said to have married Bhu-Devi. According to the South-Indian cultural practices Vishnu, Lakshmi, and Sridevi are worshiped as a trinity. It can also be observed that the delineation of Lakshmi and Bhudevi is extremely similar except for Bhu-devi’s breast-band which enables identification of the same. Here, BhuDevi is standing in the Abhanga posture on a double lotus base, her right hand holds a lotus, adorned with jewelry, hair piled into conical Jatamukuta (crown), the serene expression on her face and her almond shaped eyes are typical of the iconic style of SouthIndian bronzes.

An earlier comparable of Bhu-Devi from the Victoria and Albert Museum (IM.137-1927) depicts similar iconographic attributes of Bhu-Devi.

5

A Figure of Jambhala

Indonesia, Java 9th century Bronze

4 ½ in. (11.4 cm.) high.

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item number 1319

Provenance:

Property from the Collection of Carter Burden; Sotheby’s New York, 27 March 1991, lot 111.

Jambhala, is the principal deity of wealth in Buddhism. The present bronze from Java portrays the most ubiquitous form of Jambhala, the one face and twoarm iconography Jambhala, emerges from Tantric Buddhism making him a widely worshiped deity for good fortune and wealth. Jambhala is considered to be one of the four heavenly kings of Buddhism. Here he can be seen seated in the Ardhaparyanka posture (where one leg is lifted, and the other is on the ground, indicating a joyous and passionate Buddha nature). A similar comparable of Jambhala from Indonesia can be found in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1987.142.301).

6

Matrika Lotus Mandala

Nepal 16th-17th century

Copper alloy

Diameter: 7 ⅛ in. (18.3 cm.)

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item no. 7628.

A bronze lotus springs from a stem decorated with foliate sprays at each of the stepped base’s four corners. Each of the eight movable petals is cast to convey several layers of the closed lotus bud. The goddesses within are identified by the implements they carry and their vahanas (mounts), corresponding to those of their male counterparts: Varahi atop a buffalo, Mahalakshmi atop a lion, Maheshvari atop Nandi, Vaishnavi atop Garuda, Indrani atop an elephant, Kumari atop a peacock, Brahmani atop a goose, and Chamunda atop a corpse. The present example bears a striking resemblance to the sixteenth-century Navadurga lotus mandala at the Newark Museum of Art (acc. 90.400).

7

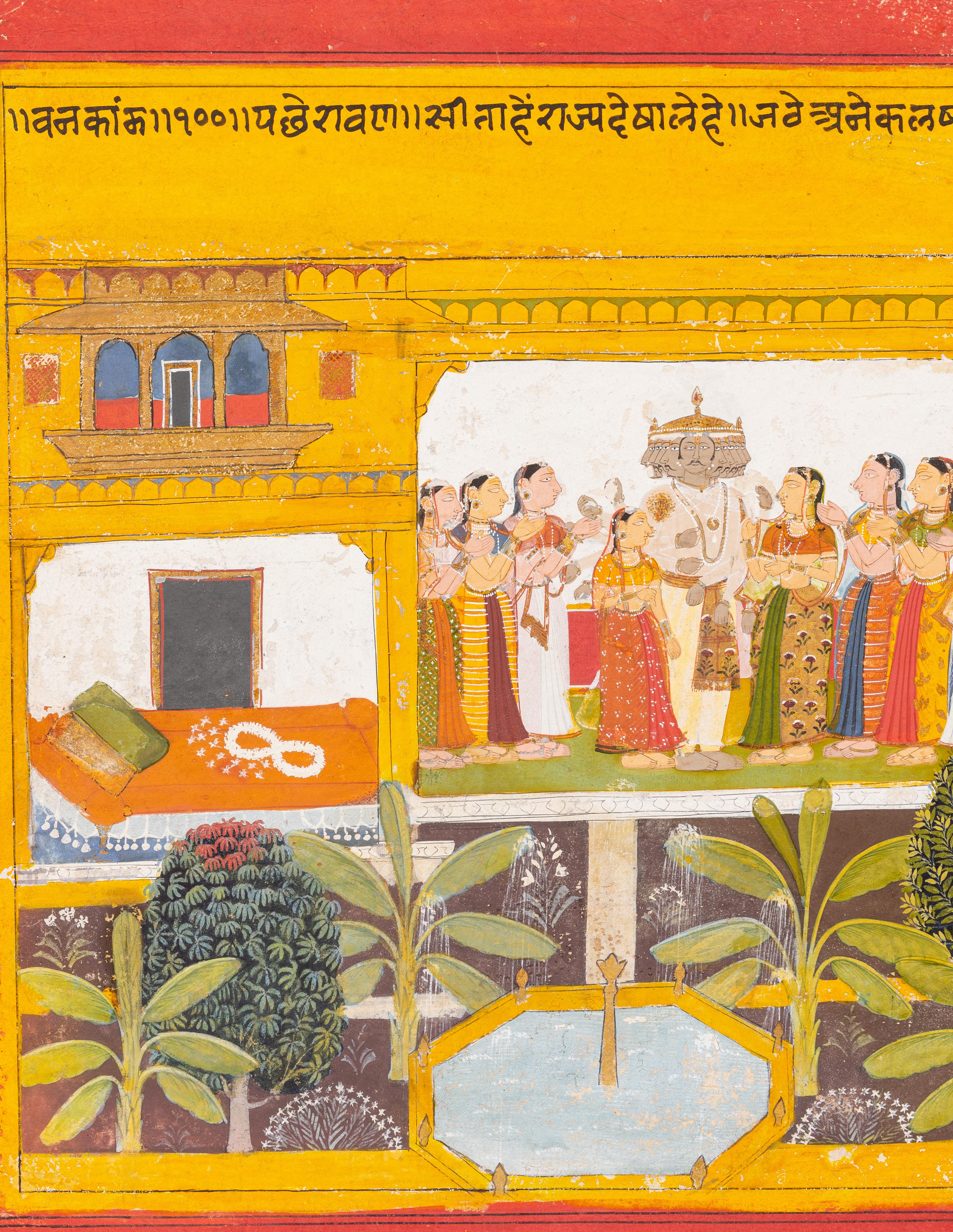

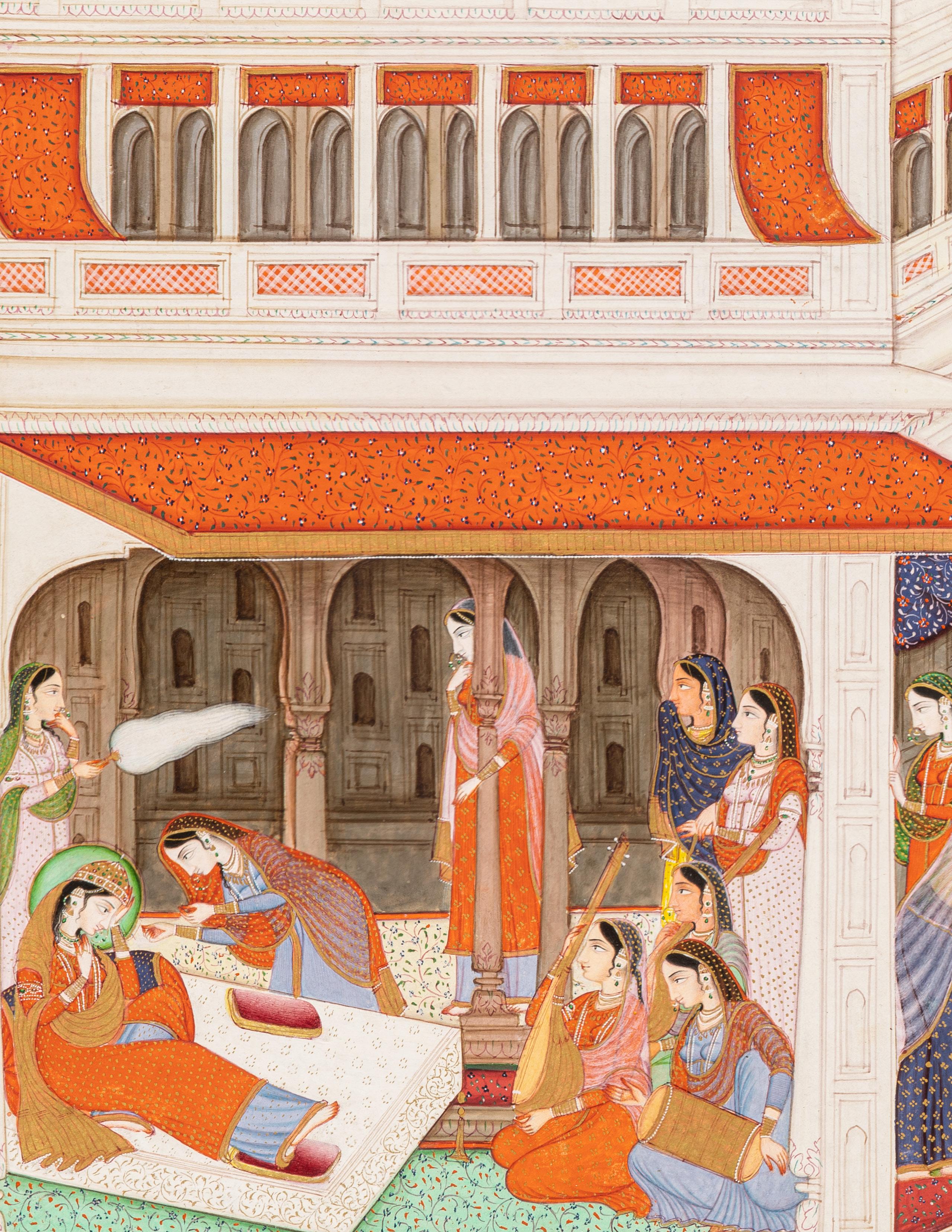

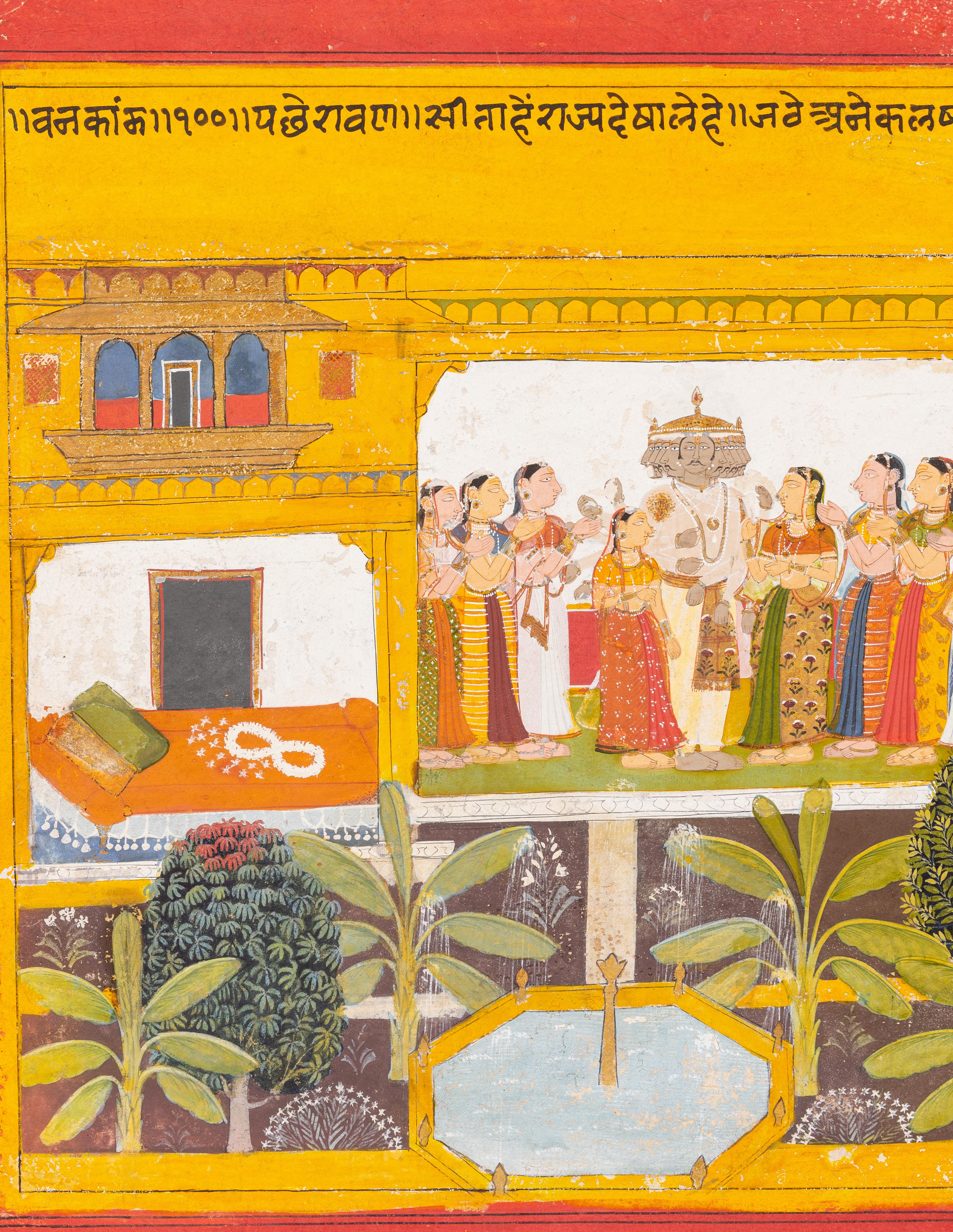

Krishna with Female Attendants

Bikaner, last quarter of the 17th century Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper Image: 8 ⅜ x 5 ⅜ in. (21.3 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 13 ¼ x 8 ⅝ in. (33.7 x 21.9 cm.)

A light blue sky descends into a mossy green, where the background meets the horizon line of a marble terrace. Green and yellow honeycomb tiles atop the garden pavilion’s roof bring out the fluid streaks of golden clouds in the sky. Floral motifs fill the textiles and panels that decorate the pavilion as well as the large bed around which three elegant female attendants wait on a regal figure, hand and foot.

The identity of the adored male herein is revealed by his sky-blue skin and the obscured peacock feather on the proper-left side of his five-pointed diadem. Krishna’s crown style resembles that exactly of a Bikaner painter Ibrahim’s 1692 Rasikapriya illustration in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art (acc. 81.192.3). The present painting exhibits figures with cinched waists, the use of linear perspective, and a gold-speckled border—all typical features of paintings from Bikaner, a major center of painting of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries within Rajasthan. The inscription which appears under the lower right corner of the painted image refers to the divine Krishna in a loving Urdu epithet, “Mohan Lal.”

8

A Prince with a Falcon

Kishangarh, 18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 9 x 5 3/4 in. (22.9 x 14.6 cm.)

Provenance:

The Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, acquired from Lawners by February 1968 (no. 41).

The present portrait may have been a noble commission to demonstrate status, as the inclusion of a falcon in the composition makes reference to the archetypal prince’s skill in hunting. This enigmatic portrait and others like it were typical of Kishangarh, particularly around the lifetime of the artist Nihal Chand (c. 1710- 1782), whose training in the imperial Mughal workshops at Delhi helped him create a popular new style of portraiture that combined Mughal naturalism with the traditional romantic and poetic idealization previously beloved in Kishangarh. The signature Kishangarh style began to develop under the patronage of Raj Singh (r. 1706-1748), and reached full-fledged actualization under Sawant Singh (r. 1748-1764). As the present painting dates to the latter part of the eighteenth century, it stands as an example of this Mughal-infused style at its most evolved.

9

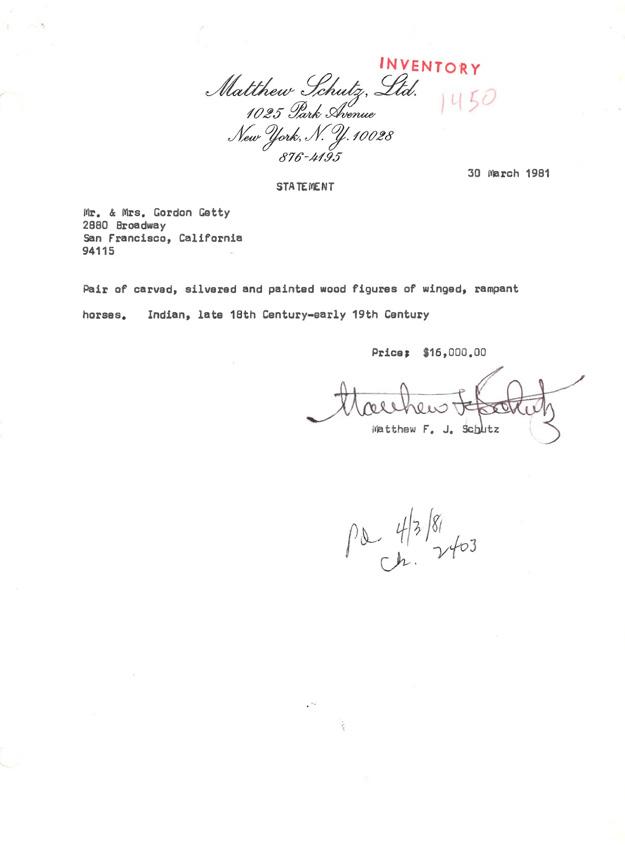

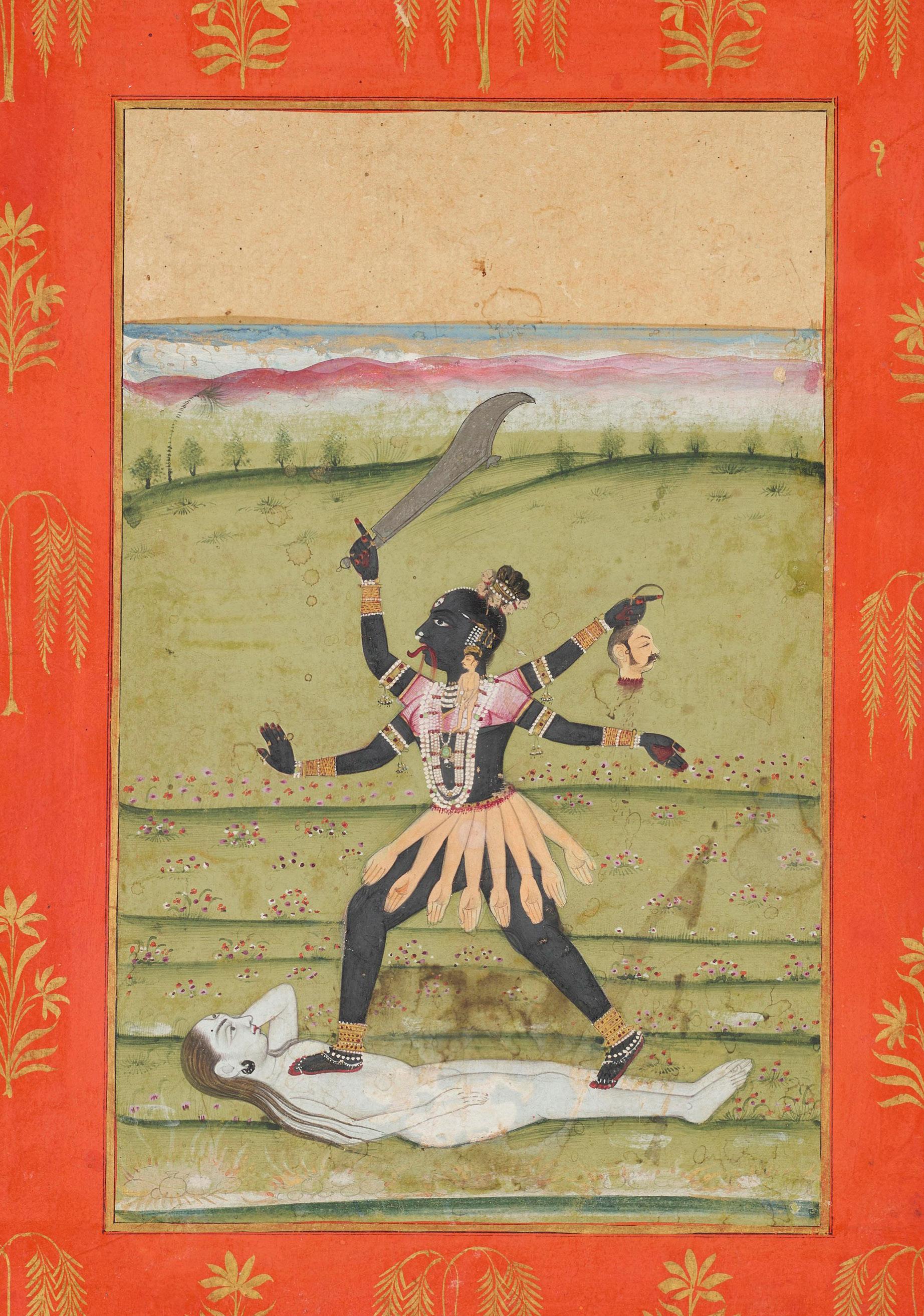

Illustration to the Devi Mahatmya:

Kali Withdraws from Vishnu

Jaipur, circa 1800

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 11 ⅜ x 7 ½ in. (28.9 x 19.1 cm.)

Folio: 11 3/4 x 7 3/4 in. (29.8 x 19.7 cm.)

Provenance:

Private French collection.

The present scene depicts the first episode of the Devi Mahatmya during the time of pralaya, the period between the cyclical destruction and creation of the universe when the primordial ocean is all that exists. Vishnu is depicted in deep sleep amongst the cosmic waters while Brahma prepares to create the next universal cycle. Brahma’s efforts, however, are interrupted by two demons who emerge to kill him. Alarmed, he attempts to awaken Vishnu to slay the demons, singing a hymn of praise. Brahma sings to the great goddess Mahamaya, the personification of Vishnu’s sleep, and asks her to release him from her spell. As Devi proceeds to retreat from Vishnu’s body she appears before Brahma. Vishnu then awakens and slays the demons, thereby acting as Devi’s instrument in restoring cosmic order.

Here, Devi appears in her form as the ten-headed Dasa Mahavidya Mahakali. This form of the goddess is relatively rare in the Indian painting tradition, as she is more commonly portrayed in her one-headed, four-armed image, trampling Shiva. However, the present form shares many iconographic attributes with the more common form. Clad in a garland of severed heads and skirt of dismembered arms, Kali holds items representing the powers of each of the gods in her ten hands: a severed head, trident, bow, mace, conch, sword, and chakra. Her outstretched tongues, bared teeth, long unruly hair, large nimbus and strong stance convey her fierceness. Below, Vishnu reclines, and Brahma emerges from Vishnu’s navel on a lotus, flanked by the demons Madhu and Kaitabha. Fine lines of water and lotuses comprise the cosmic ocean, while a horizon of foliage bisects the background with a pale blue-grey sky above. This partitioning of the background reinforces the hierarchical scale of the painting and thus emphasizes Kali’s great power.

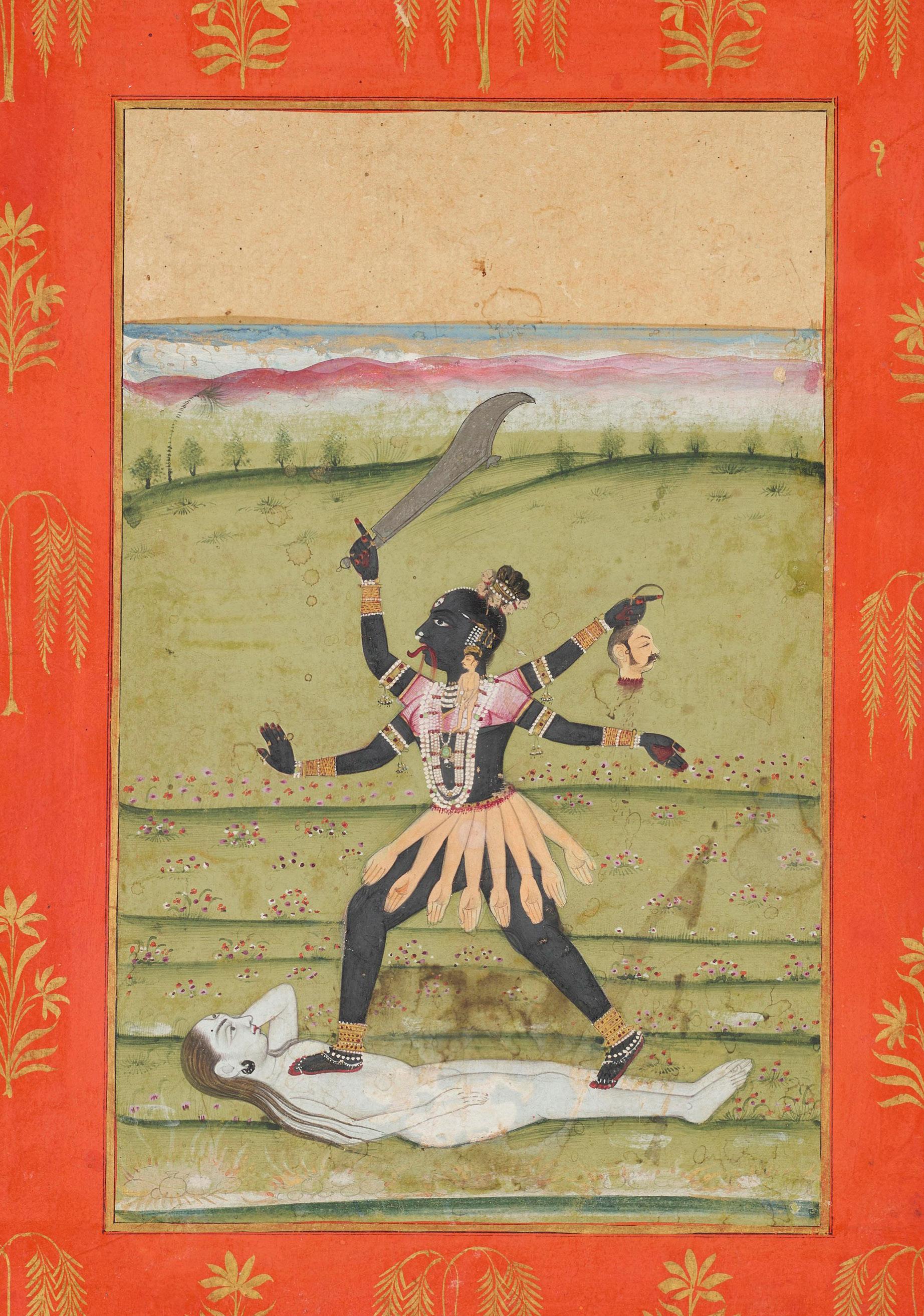

10

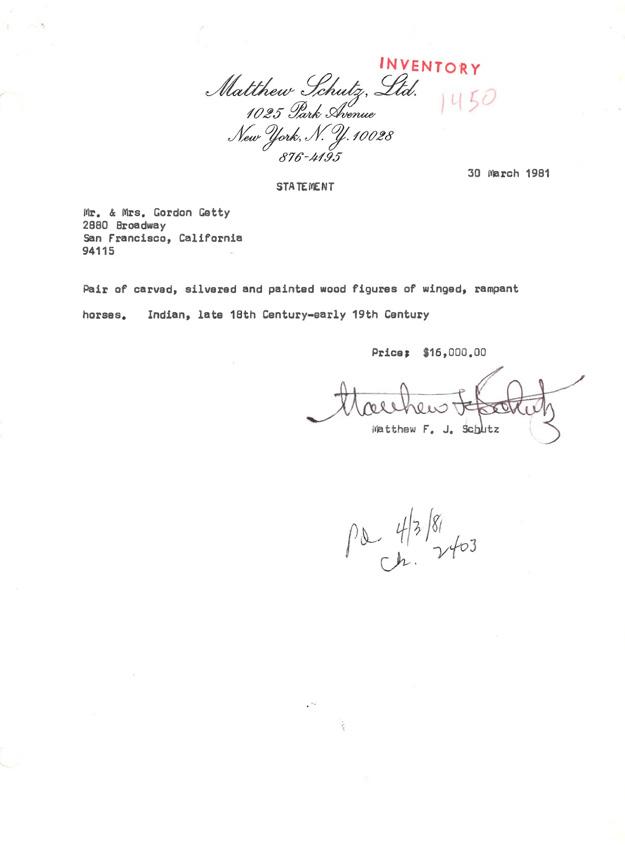

Kali Trampling Shiva

Rajasthan, Jaipur, 18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 ⅛ x 4 ½ in. (18.1 x 11.4 cm.)

Folio: 9 7/8 x 7 ¼ in. (25.1 x 18.4 cm.)

Provenance:

Nik Douglas, British Virgin Islands, 17 December 1982. The James and Marilynn Alsdorf Collection, Chicago.

According to Hindu mythology, there was once a powerful demon named Raktabija who received a boon allowing him to replicate himself whenever a drop of his blood touched the earth. When the demon engaged in battle with the gods, Kali spread her tongue over the battlefield to prevent any of the demon’s blood from hitting the ground, thus facilitating his defeat. Kali, however, became drunk with bloodlust and after her victory, the goddess went on a rampage. She proceeded to kill anyone who crossed her path, adorning herself with the dismembered parts of her victims. Afraid that Kali would not stop until she destroyed all the cosmos, Shiva laid down on the battlefield in her path. Upon seeing her consort beneath her foot, she suddenly realized her mistake and halted her spree.

This painting illustrates the moment Shiva pacifies Kali, appearing in her form as Dakshinakali, the benevolent mother. Dakshinakali is typically depicted with her right foot on Shiva’s chest, while her more fearsome form as Vamakali is usually shown with her left foot on his chest. She holds a severed head and scimitar in two of her four hands and wears a skirt of dismembered arms from her rampage. Kali’s typical garland of severed heads is replaced here with a string of severed heads around her chignon, and her large, outstretched tongue drips with the blood of her victims. A pale, prostrated Shiva lays below, gazing up at Kali. By presenting Kali as literally trampling Shiva, this archetypal image demonstrates the extent to which Shiva’s transcendental power is only possible through interaction with Kali.

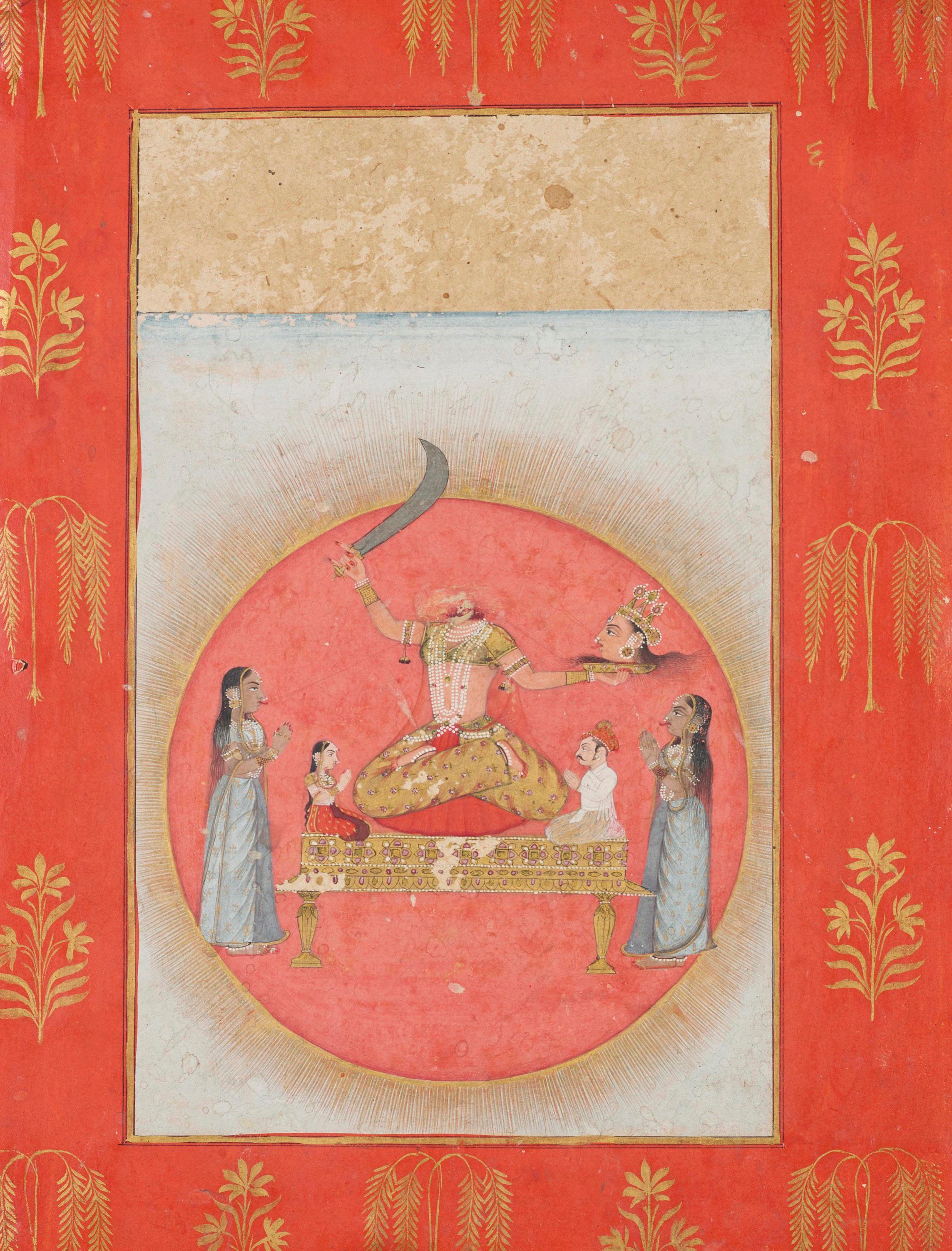

11

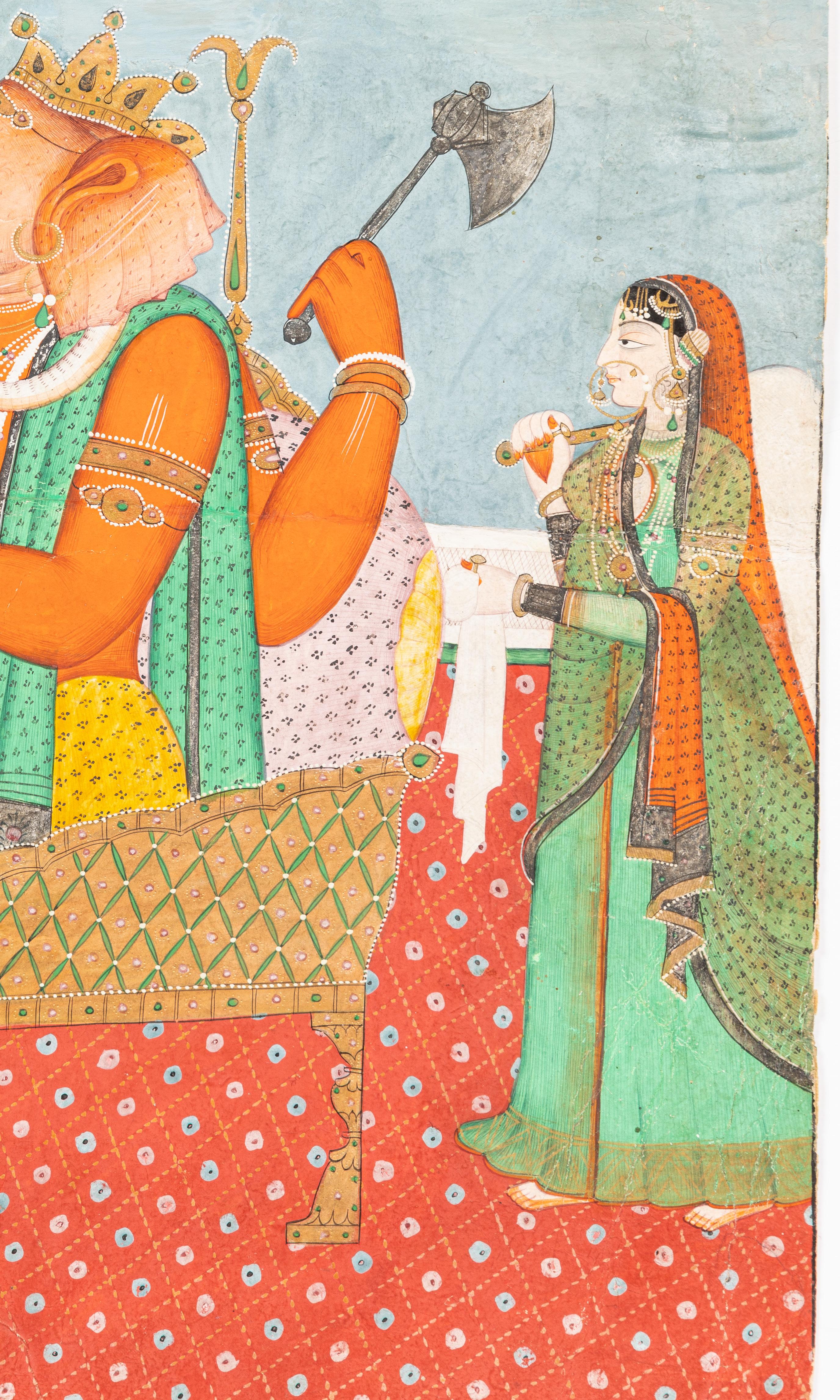

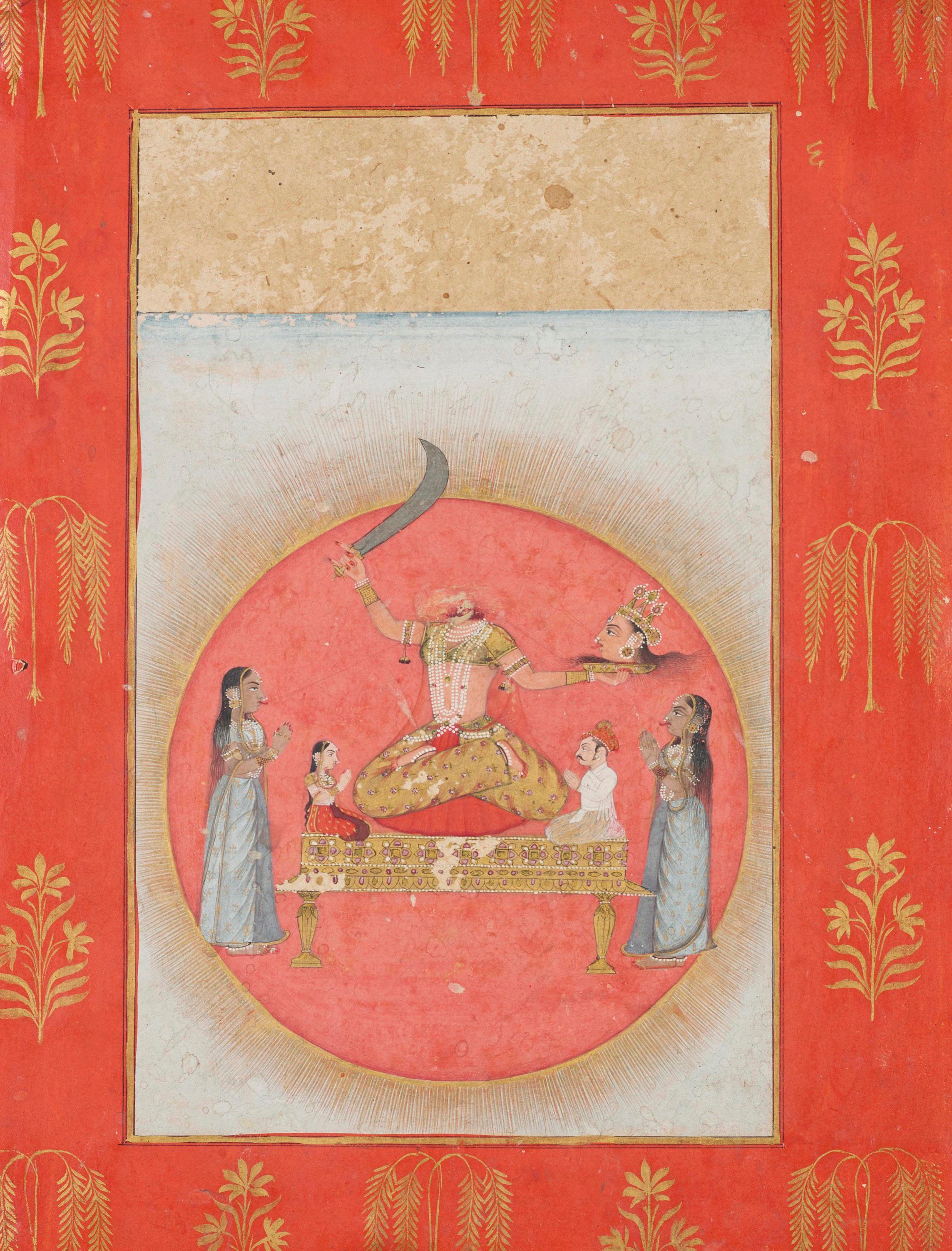

Chinnamasta

Rajasthan, Jaipur, 17th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 ⅛ x 4 ½ in. (18.1 x 11.4 cm.)

Folio: 8 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. (22.5 x 17.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Nik Douglas, British Virgin Islands, 17 December 1982. The James and Marilynn Alsdorf Collection, Chicago.

In the Hindu tradition, Chinnamasta (or ‘Severed Head’) is one of the ten mahavidyas (incarnations of the great goddess Devi). According to the Pranatosinitantra, Parvati was bathing in the wilderness with two yoginis, Dakini and Varnini, when they became famished. Parvati resolved to decapitate herself so that they may be nourished by her blood, thus embodying Chinnamasta.

Here, the goddess appears seated on a throne, worshiped by a ruler and his wife kneeling beside her, holding a scimitar in her right hand and her own head on a platter in her left. A crown sits just above her third eye, while thin wisps of hair hang loose and her tongue lolls. The goddess is adorned with pearl and emerald jewelry, and her skin is rendered a characteristic orange-red complexion. Thin streams of blood can be seen flowing from her neck to the mouths of the yoginis that flank her. Chinnamasta’s iconography encompasses elements of both terror and heroism by way of severing her own head and then offering her blood for nourishment, ultimately symbolizing the transformations of death and life.

12

Lalita Maha Tripura Sundari

Mandi, Style of Sajnu, circa 1810

Opaque watercolor heightened with silver and gold on paper

Image: 9 ⅛ x 5 7/8 in. (23.2 x 14.9 cm.)

Folio: 11 3/4 x 8 ¼ in. (29.8 x 21 cm.)

Provenance:

Royal Mandi collection. Acquired by the present owner on the UK art market.

The majesty of this supreme shakti is perfectly captured by this finely decorated Pahari composition. Her beauty, as her name indicates, transcends the vast Tripura (three demon citadels) within which she is believed to have defeated many demons. For she is the transcendent form of the supreme Devi Parvati and rules over the Trimurti (divine triad) of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Thus, she is also known as ‘Raja Rajeshwari,’ meaning the ‘Queen of all Kings and Rulers.’

The mahavidhya’s power is not only captured by her elaborate enthronement and godly ornamentation, but also by the ethereal gaze the artist rendered so well; her wide and bright third eye clearly visible in this rendering of the deity in profile. Her identity is revealed by her red skin and her four arms, two of which hold an elephant goad and a lasso.

Her identity is corroborated by a small painted image, pasted within the border atop the painting folio depicting the Parvati yantra: a six-pointed star within an eight-petaled lotus surrounded by a square with gates in the four cardinal directions. It is typical to find such an associated yantra as the worship of shaktis always incorporates these diagrammatic mystic charms. Such worship consists in throwing kumkuma (vermilion powder) over the yantra while speaking aloud the many epithets of Lalita Maha Tripura Sundari.

The present subject is rare among published paintings, however, one example can be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum, though it is currently identified as Kali (acc. CIRC.660-1969). The present painting, however, differs quite distinctly in style as it can be attributed to the style of Sajnu, the master artist who is credited with bringing the sophistication of Kangra and Guler paintings of the time to Mandi. Her profile, in particular, resembles many subjects executed by Sajnu (see Archer, W.G., Indian Painting from the Punjab Hills, Sotheby Parke Bernet, London, 1973, Mandi no. 43).

Here, Lalita appears enthroned atop the terrace of a marble palace; a pietre-dure arch between two marble pillars frames the goddess. The black margin with floral petal and leaf scrolls in white and gold meets a redspeckled yellow border. This follows, as Sajnu is known for the use of spandrels to frame his compositions and an exquisite use of florals.

13

Miniature of a Hunting Party

Mewar, 19th century

Gouache, ink and gilt on paper

13.29 x 10.03 in. (34 x 25.5 cm.)

The painting, showcasing a collective feast preparation scene in Mewar, reflects a fascinating blend of Mughal and Rajput stylistic features. The Mughal influence is evident in the clothing and rendering of human figures, demonstrating a harmonious integration of two distinct artistic traditions. Notably, the verso of the artwork contains text, presumably in Mewari, partly translating to “they’re cooking pulav” — a rice preparation. This linguistic element adds an intriguing layer, providing cultural context to the scene.

Dating back to the 16th century, a period marked by a balanced exchange between Mughal and Rajput painting elements, this artistic fusion was commonplace. Akbar’s atelier exemplifies this exchange, where Rajput elements found a place alongside Mughal influences, as described by Hajek in Indian Paintings of the Mughal School. The power dynamics of this cultural exchange reveal a reciprocal relationship that shaped the artistic landscape.

As the 17th century unfolded, Rajput art gradually yielded ground to the assimilation of Mughal influences. The present painting, attributed to Mewar, exemplifies this evolution, showcasing a strong adaptation of Mughal stylistic rendering and material culture. Noteworthy elements include Surahi-like elongated pots and the depiction of a man wearing a transparent Jama (overlapping coat) with a Patka (sash), distinctive of Mughal attire.

Drawing parallels with Plate 24 in Hajek’s Indian Miniatures of the Mughal School – which portrays a Mughal military camp scene – the present artwork likely captures a royal hunting feast. The similarity in the delineation of the encampment suggests a shared artistic language. The background, adorned with foliage and terrain typical of Rajasthani miniatures, further enriches the visual narrative. It is in this melding of Rajput and Mughal sensibilities that the painting derives its harmonious charm.

14

15

Yoshida Hiroshi

Maharu no asagiri daigo (Morning Mist at Taj Mahal no.5), 1932

Woodblock print, signed in ink Yoshida, in pencil in Roman script Hiroshi Yoshida, sealed, on left margin sealed Jizuri (self-printed)

15 3/4 x 21 3/4 in. (40 x 55.2 cm.)

16

Yoshida Hiroshi

Taji Maharu no yoru, dai roku (Night in Taj Mahal, no 6), 1932 Woodblock print, signed in ink Yoshida, in pencil in Roman script Hiroshi Yoshida, sealed, on left margin sealed Jizuri (self-printed)

15 3/4 x 21 3/4 in. (40 x 55.2 cm.)

Renowned for his mastery in the Shin-Hanga (new print) style, the 20th-century artist Hiroshi Yoshida left an enduring legacy as a woodblock printmaker, as exemplified in the following Jizuri print (marked on the left margin). The term “Jizuri,” meaning selfprinted, serves as a pivotal indicator that Yoshida personally supervised the entire printing process.

Yoshida’s prints radiate a meditative allure with their gentle contours. He skillfully crafted woodblock representations of both man-made and natural landmarks worldwide, seamlessly blending traditional Japanese techniques with Western artistic sensibilities—a hallmark of the Shin-Hanga Style. Presently; the present two Jizuri woodblock prints showcase the Taj Mahal in both daylight and nighttime settings.

In the gentle dawn light, the marble Taj Mahal’s dome illuminates, casting a serene reflection on the Yamuna’s placid waters, capturing the essence of this monumental landmark and its surroundings. The symmetrical composition, coupled with the interplay of light and shadow, renders the entire scene dynamic yet tranquil.

Similarly, a nocturnal portrayal of the Taj Mahal in the subsequent print employs a subdued color palette, highlighting Yoshida’s adeptness in navigating the nuanced shifts in printing techniques.

A compelling comparison to this pair is found in a set of Mount Fuji prints (JP3496) housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, offering a fitting parallel to the artistic prowess displayed in the present collection.

Yoshida Hiroshi

Caravan from Afghanistan, 1932

Woodblock print, signed in ink Yoshida, in pencil in Roman script Hiroshi Yoshida, sealed, on left margin sealed Jizuri (self-printed)

11 ⅛ x 15 3/4 in. (28.3 x 40 cm.)

Yoshida Hiroshi

Caravan from Afghanistan: moonlit night

Woodblock print, signed in ink Yoshida, in pencil in Roman script Hiroshi Yoshida, sealed, on left margin sealed Jizuri (self-printed)

11 ⅛ x 15 7/8 in. (28.3 x 40.3 cm.)

The featured prints capture the essence of Yoshida’s extensive travels, offering a glimpse into a scene from Afghanistan. The artwork portrays a caravan traversing through the desert, with a tonality characterized by a subdued and earthy palette. The interplay of shadows cast by both human figures and animals imparts a distinct character to the print, while the expansive arid landscape, adorned with distant mountains and a pale blue sky, beckons the viewer into the vastness of the desert.

In a complementary counterpart to the daytime depiction of the caravan, the moonlit rendition of the same scene conjures the serene nocturnal atmosphere surrounding the caravan. A deep blackish-blue blanket envelops the desert backdrop, rendering the background and landscape nearly invisible. Yoshida’s masterful use of a striking color palette in both the day and night scenes exemplifies his artistic prowess, showcasing his ability to create multiple renditions of the same scene with compelling nuance and skill.

17 18

A large stucco hand of Buddha

Gandhara, 3rd century 15 in. (38 cm.) high.

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item number 1324.

Provenance:

Japanese Collection, acquired in 1990s.

Christie’s New York, Indian and Southeast Asian Art, 16 September, 2008, lot 325.

Finely casted, the present sculpture of Buddha’s right hand with all five fingers extended in Abhaya Mudra (gesture of fearlessness) with fine detailed creases in his palm and fingers consisting of red pigment remains overall. A symbol of reverence, the hand here stands for Buddha himself. It also brings to attention the paramount significance of Mudras in Buddhist art and in the Buddhist religion at large. Mudras are a set of hand gestures symbolizing Buddha’s various roles and states of mind. Mudras have often, if not always, been pedagogical tools used to refashion Buddhist religious doctrine into comprehensible symbolic narratives.

Buddhism reached Gandhara in the third century B.C. The present sculpture from the same timeperiod makes it a coveted object from the origins of Gandharan Buddhism.

19

Bhim Singh with Attendants

Attributed to Baghta, father of Chokha Mewar (formerly attributed to Deogarh/Devgarh), 19th century Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 6 ⅝ x 9 ½ in.

Provenance:

Private American collection.

Rubin-Ladd Foundation, no. I-1415.3.

This painting, attributed to the Rajput school of painting and created by the artist Baghta, reflects the distinctive style of the Mewar school. Baghta commenced his artistic journey in Udaipur in 1761, evident from signatures on works portraying hunts and darbars. In response to the volatile political climate in Udaipur, he relocated to Devgarh in 1769, maintaining an active career until 1814.

The artwork captures Maharana Bhimsen enjoying a hookah in the company of female attendants, showcasing the influence of Mughal paintings on Rajasthani court art. Noteworthy is Baghta’s meticulous detailing of jewelry and textiles, exemplifying the finesse of the Mewar school, renowned for its miniature paintings in India.

Baghta’s penchant for minimalist backgrounds directs attention to the painting’s focal point. The halo surrounding Maharana Bhimsen adds to his regal aura, emphasizing his noble lineage. The use of bold colors, strong profiles, and a subdued background collectively conveys the opulence inherent in Rajput courtly life.

20

A Nayika Writing a Note

Kangra, circa 1810-1830

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 ¼ x 6 in. (21 x 15.2 cm.)

Folio: 9 3/4 x 7 3/4 in. (24.8 x 19.7 cm.)

Within the frame of an arched window, a nayika (heroine) sits on a carpeted terrace dressed in a flowing green sari and orange veil with gold trim. She wears large ear and nose rings, strands of pearls and numerous jewels and ornaments. Her female companion awaiting the finished note to deliver to her beloved. Below, writing implements on a covered gold and jeweled plinth appear along with a knife, scissors, a small gold cup and a bowl.

The central female represents the consummate Kangra heroine, with a demurely lowered gaze and an archetypal profile, sharply defined features and jetblack hair. Her fine nose, small red lips and shapely chin are enhanced by her subtle smile. Whether the figure is a courtesan or princess, this is an idealized rendering of a nayika, her features displaying the classic look of a perfect Pahari heroine found in countless miniatures since the development of the Kangra style. The present painting is a wonderful example of the pan-Pahari style of Kangra originated at Guler as a response to the increasing influence of naturalistic Mughal painting.

21

Maiden with a Mirror

Kangra, circa 1810

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 4 7/8 x 3 ⅝ in. (12.4 x 9.2 cm.)

Folio: 6 x 4 7/8 in. (15.2 x 12.4 cm.)

Provenance:

The Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968 (no. 39).

The wide and focused eye of the young maiden directs the viewer’s gaze directly to the figure’s hand with which she applies kajal in a mirror held by an affectionate child. She has already adorned herself with a tikka (hair ornament), nath (nose ring), earrings, necklaces, armbands, and rings. The vermillion on each of her fingertips matches that of the three layers of her diaphanous garments, decorated with green edges matching the window valence above. She appears to be preparing herself for an important event for which the child below has already been groomed. The child’s lavender dress matches the magenta and yellow textile that hangs over the base of the window, creating a pleasingly cohesive color palette.

The charming portrait is unmistakably Pahari, epitomizing a bold and colorful tradition that embraces naturalistic Mughal techniques. This type of architectural framing (a view through a window) is typical among paintings from Kangra, in particular, as is the deep blue border with a gold foliate motif and a secondary support of speckled pink paper.

22

Illustration to Kirata-Arjuniya Episode, From a Mahabharata Series

Kangra, circa 1820

Opaque Watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 13 3/4 x 18 ½ in. (34.93 x 47 cm.)

Folio: 15 ½ x 19 7/8 in. (39.4 x 50.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired from the Doris Weiner Gallery by repute. Private Virginia collection, thence by descent.

A Sanskrit epic, written by Bhairavi in the 6th century, the Kirata-Arjuniya episode revolves around the encounter of Pandava Prince Arjun with Lord Shiva (in disguise of a Kirata, a mountain dwelling hunter).

During the Pandavas’ exile, Arjuna encountered a demon in the form of a boar. After Arjuna killed the boar in self-defense, a dispute arose with Shiva, disguised as a hunter, claiming he had shot first. Despite Arjuna’s use of divine weapons, he couldn’t defeat the hunter. Recognizing the hunter as Shiva, Arjuna sought forgiveness. Shiva revealed his identity, and blessed Arjuna with powerful weapons, including the Pashupatastra, strengthening him for the Kurukshetra War.

This artwork beautifully encapsulates the quintessence of the Kangra style by incorporating a distinctive bold border adorned with foliate motifs that gracefully traverse the composition. The airbrushed portrayal of trees and the opulent landscape, coupled with the application of linear perspective for depth, depicts the typical Kangra paintings of its era. Notably, the majority of figures are depicted inside or quarter profile. The meticulous detailing of weaponry, jewels, and clothing in the depictions of Arjuna as a warrior prince and Shiva as the Kirata hunter underscores the exquisite artistry inherent in Kangra miniatures.

Refer to a similar painting (M.70.38.1) from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art which comprises the same subject matter.

23

The Boar

Opaque pigments on paper

Image: 8 3/4 x 7 in. (22.2 x 17.8 cm.)

Folio: 10 x 8 ½ in. (25.5 x 21.6 cm.)

Published:

J. Bautze, Indian Miniature Paintings c.1590–c.1850, exhibition catalogue, Amsterdam, 1987, no.23, p.61.

Exhibited:

“Indian Miniature Paintings” c.1590–c.1850, Amsterdam, 1 October–30 November 1987, no.23.

Provenance:

Christie’s Amsterdam, 12 October 1993, lot 34.

Christie’s London, 12 June 2018, lot 28.

Inscribed in Sanskrit:

Loss of property, mental anguish, Death of sons, terrible fear, Death, sorrow, suffering: A boar indicates all this.

(translation by Dr. Harsha Dehejia)

The present image depicts a lone boar, standing at the river’s edge. Its finely rendered hair and almost human eyes belie a robust figure with dangerously pointed tusks. The rust colored sky creates an ominous air—a sense of danger. According to the Sakunavali, the boar, categorized as ‘neshta,’ is an ill omen.

The rendering of the landscape, with the river’s zigzagging indentation of the foreground, and the differentiated colored background in rust and blue, are conventions of the Sangram Singh period. Compare the treatment of the water’s edge to a folio from the Sat Sai, produced in the same workshop (see A. Topsfield, Court Painting at Udaipur Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar, Zurich, 2002, p. 144, fig. 116).

24

Illustration from the Ramayana

Nepal, 18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 8 x 11 3/4 in. (20.3 x 29.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Doris Wiener Gallery, inventory no. P1548 (label on frame).

The present painting, though lacking inscriptions, seems to illustrate a portion of the Ramayana, as the three figures on the right side of the composition resemble the exiled triad at the center of the Indian epic: Krishna’s avatar Rama, his betrothed, Sita, and his brother Lakshmana. The seven sages depicted, however, may very well be the saptarishi or celestial brothers born from Brahma.

While the subject-matter is difficult to elaborate upon, the present is discernibly Nepalese, particularly in palette. The prominent bright reds and blues and heightening with gold closely resemble the pigments used in a well known dispersed eighteenth-century Nepalese Bhagavata Purana series executed in a large format of which two folios reside in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc. 2019.64). The crown and ornamentation style, however, very closely resemble the style of those in a circa-1700 painting from Bilaspur depicting only Sita, Rama, and Lakshmana on a red ground in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (acc. M.87.278.10). Thus, the influence of Indian miniature painting is also evident in this unusual Nepalese illumination of a Hindu epic.

25

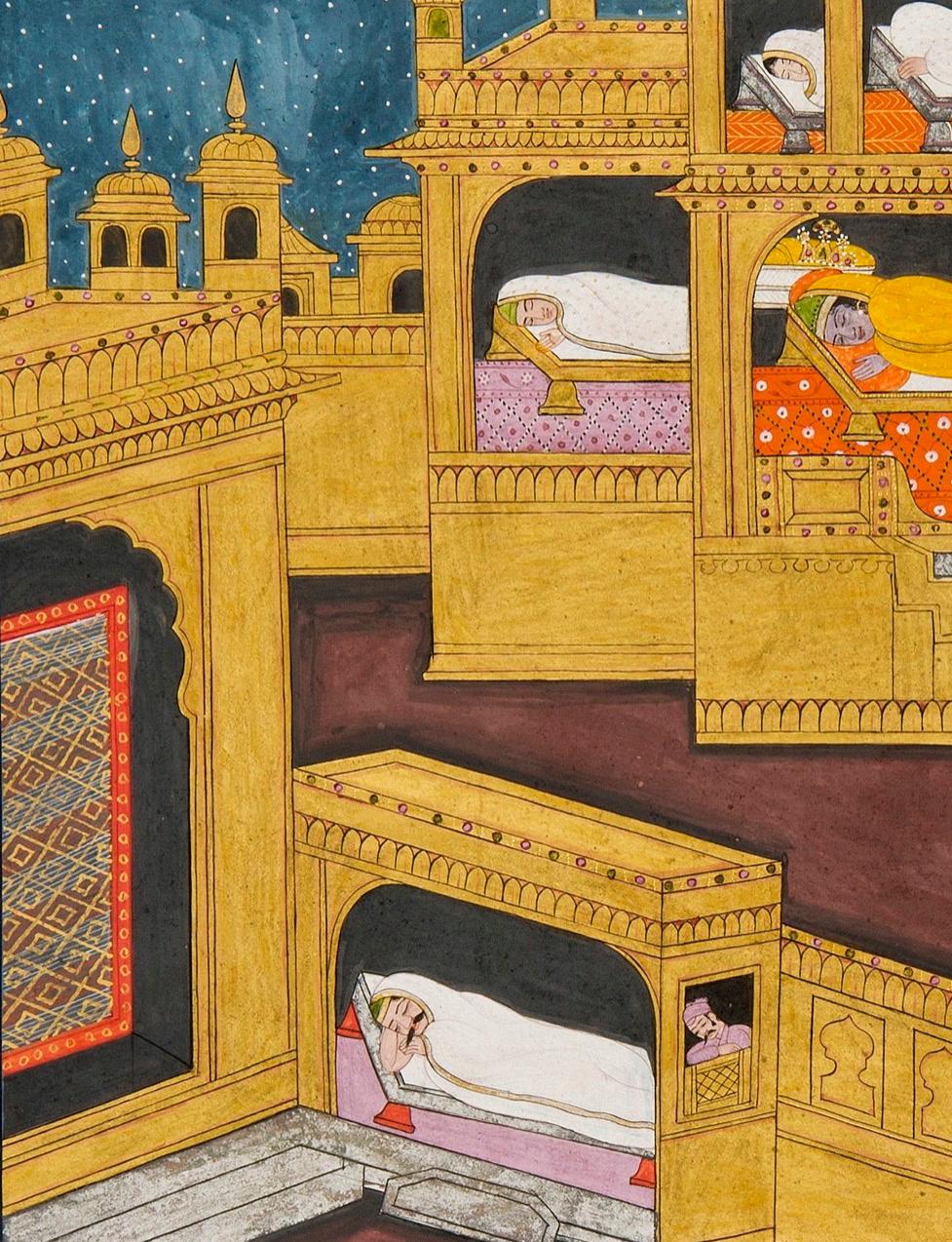

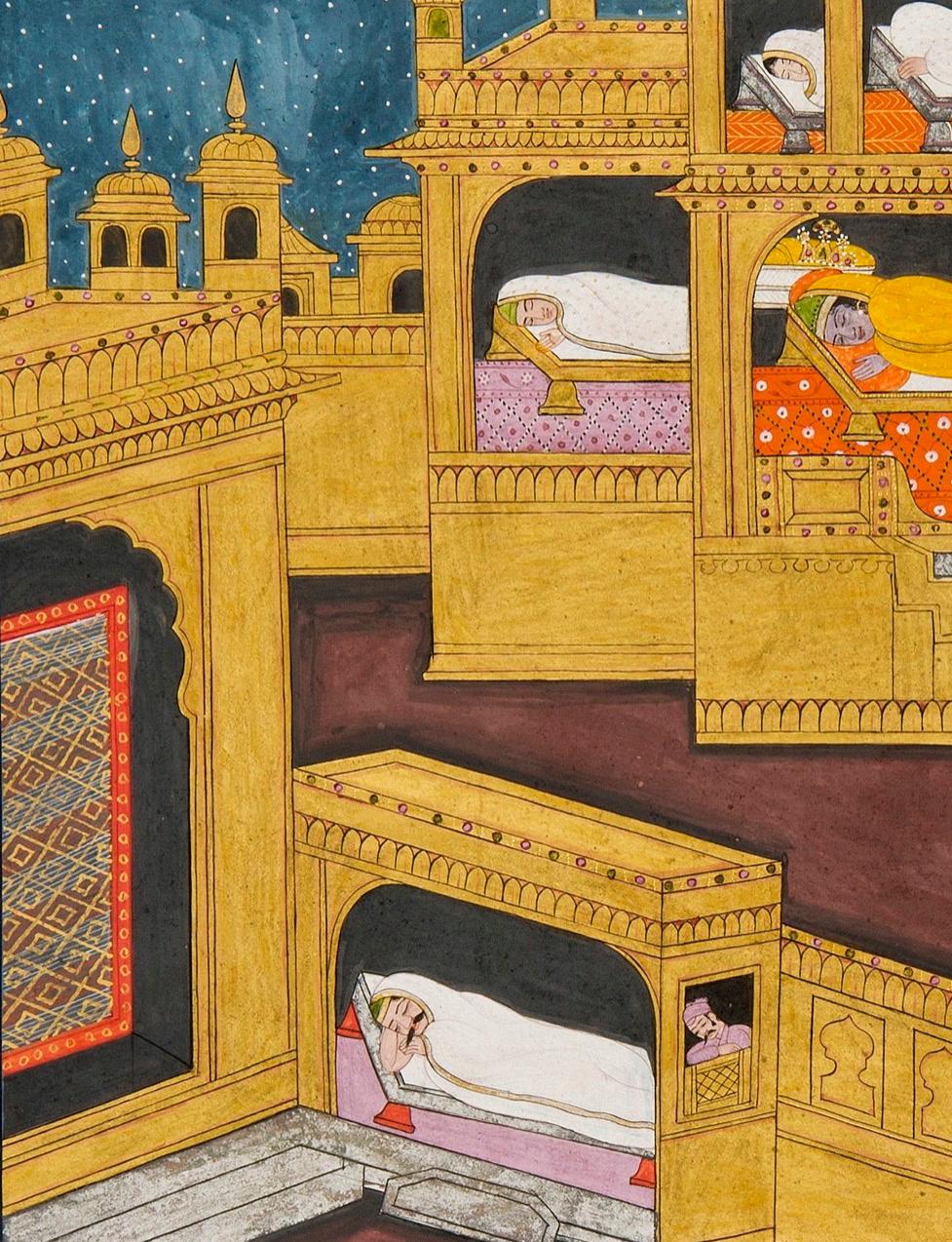

Two Illustrations from the Ramayana: Sita in Ravana’s Palace

Mewar, early 18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 8 3/4 x 15 in. (22.2 x 38.1 cm.)

Provenance:

Purchased in the U.S. in 1972 and descended in the Steig family.

In the present two contiguous illustrations (numbered ‘99’ and ‘100’) of the Aranyakakanda book of the great Ramayana, the demon King Ravana appears in his palace surrounded by his wives and the daughters of gods and other divine creatures he has previously captured. Before him stands Sita, the wife of Rama, who he has imprisoned. His fortress at Lanka is guarded by his animal-headed minions.

Both folios are representative of a playful style associated with the Rajput principality of Mewar. The red and yellow borders, the prominence of primary colors in the overall compositions, the execution of foliage with pointed leaves splaying out in a circular fashion from a central point; and the sharp profiles of each figure, closely match that of a folio from a dispersed manuscript depicting Rama and Lakshmana searching the forest for Sita dated to circa 1680-1690 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (acc. 1974.148).

26

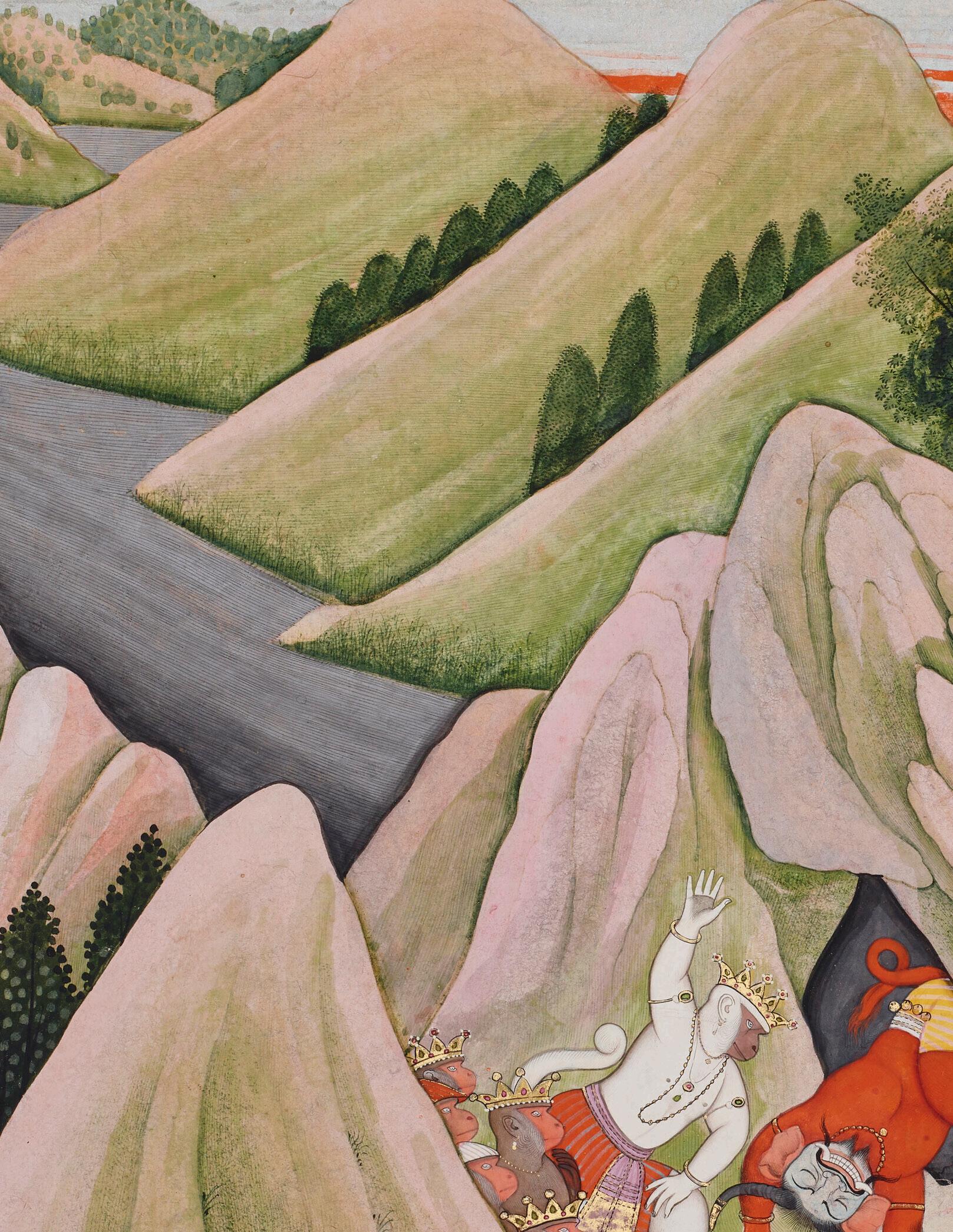

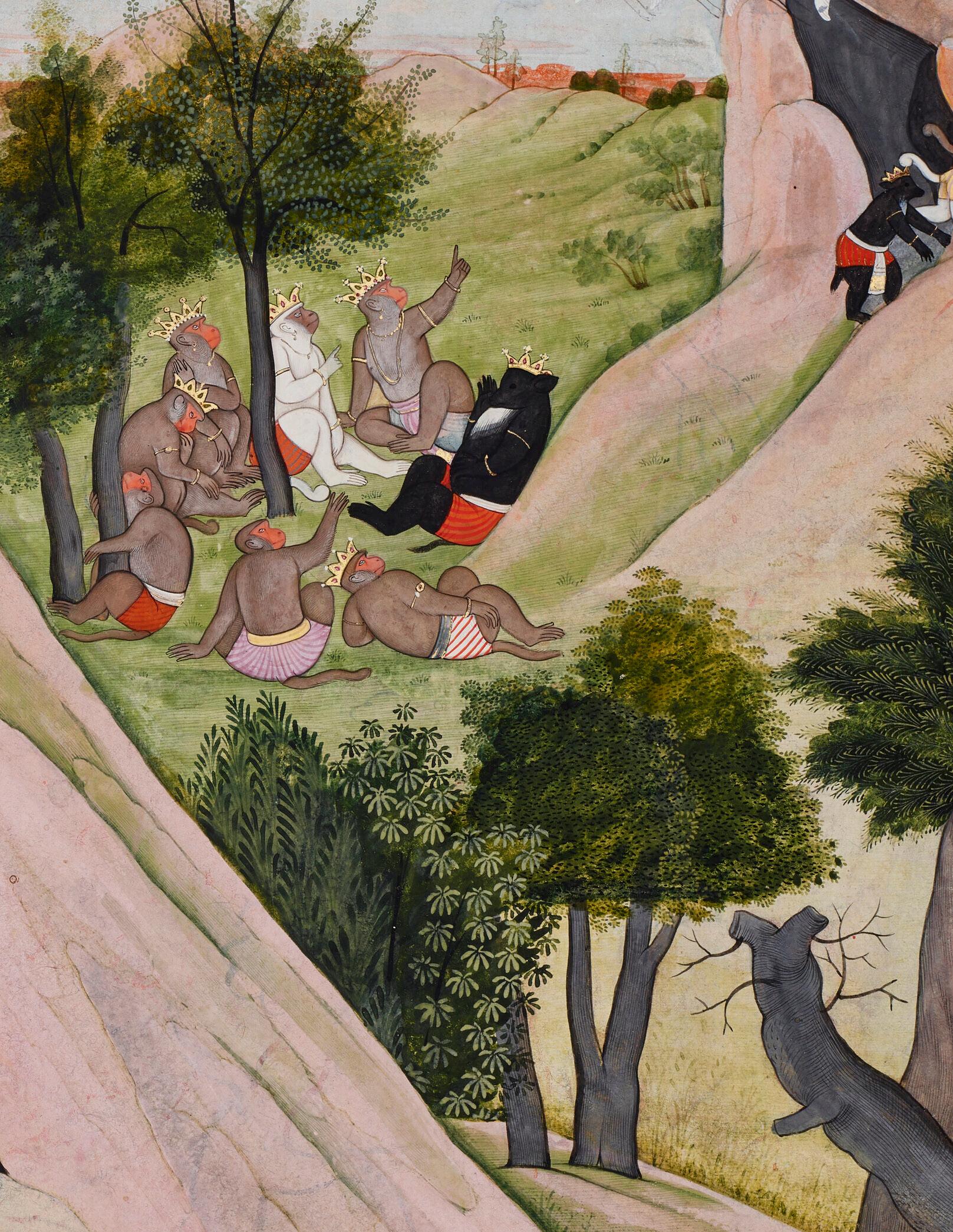

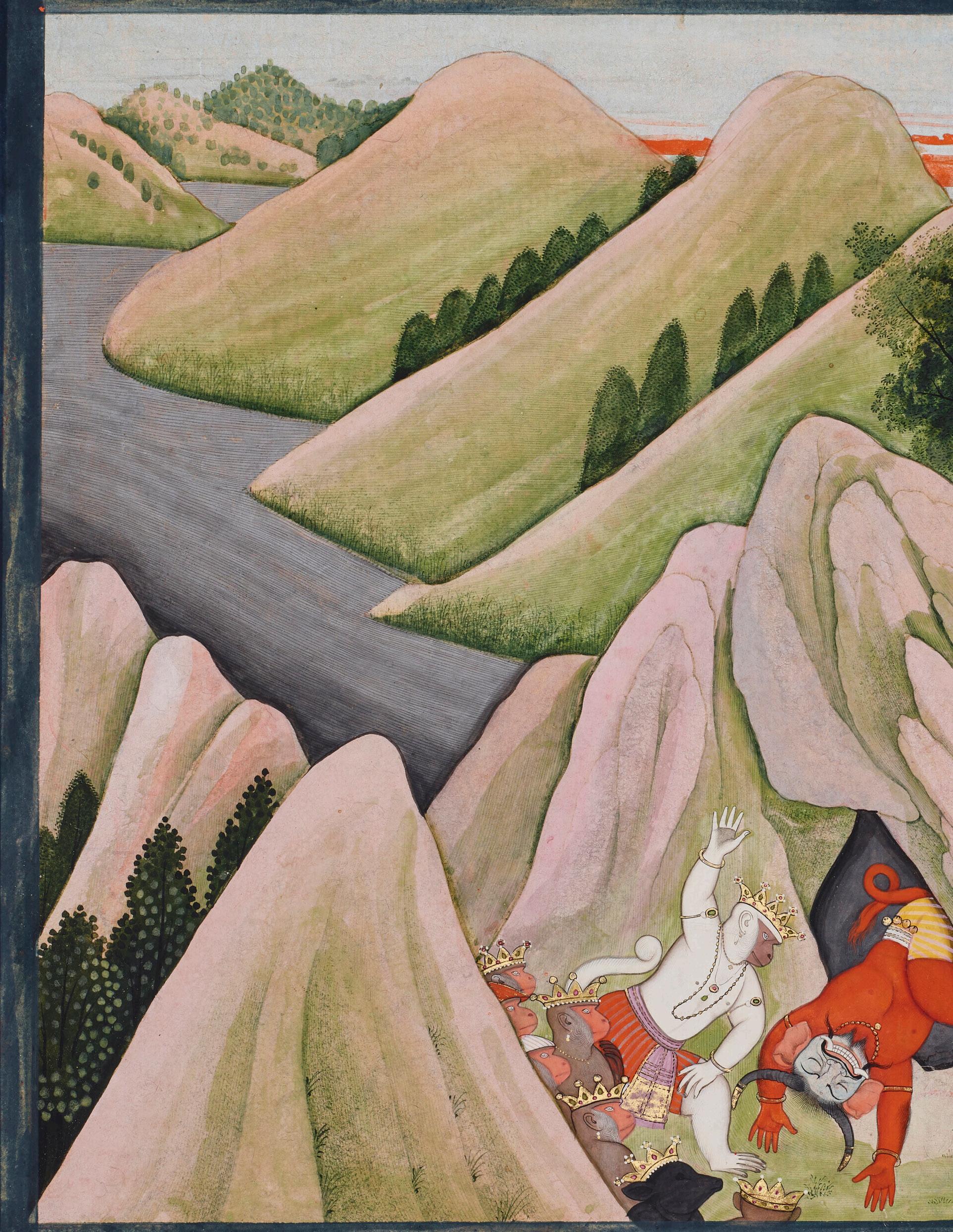

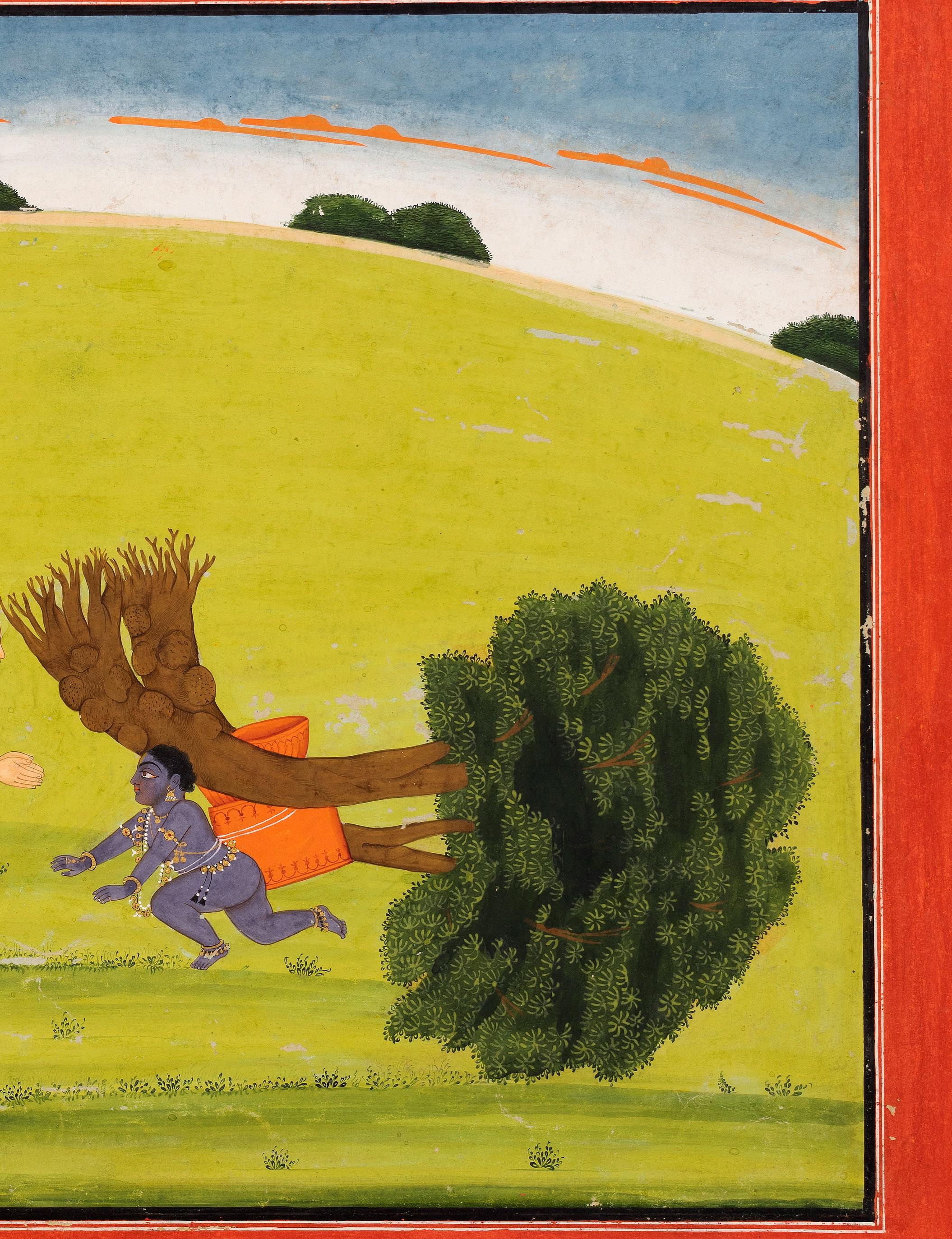

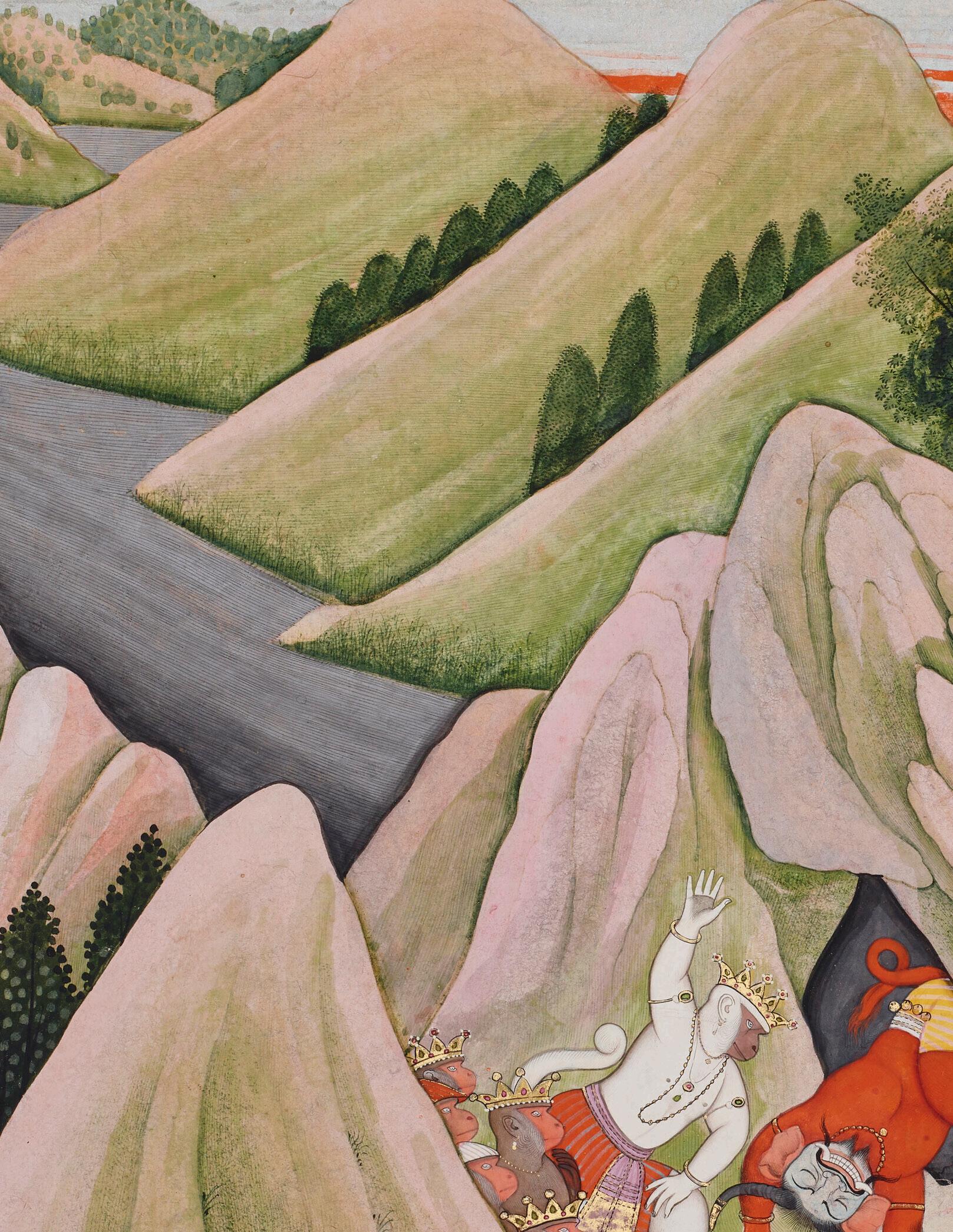

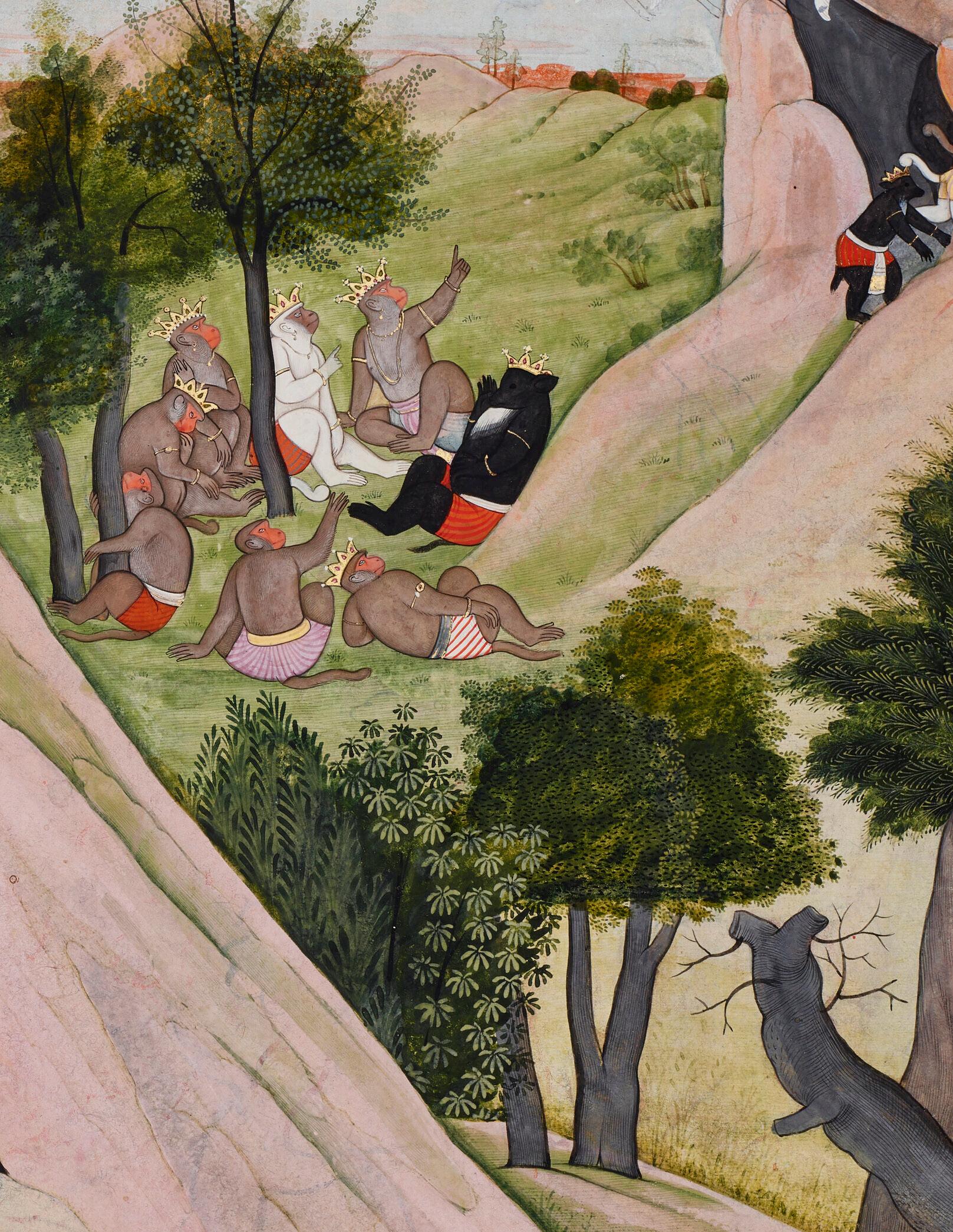

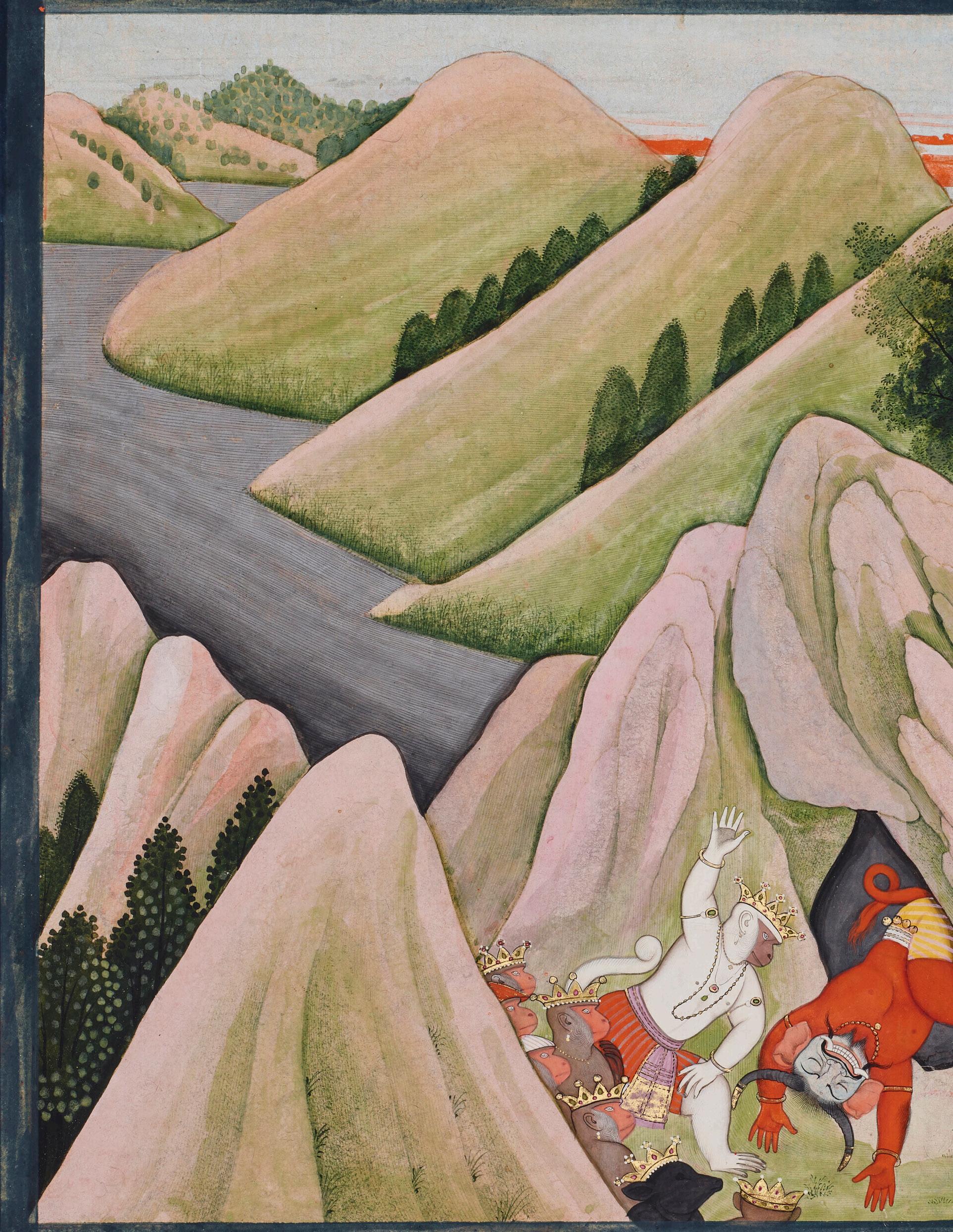

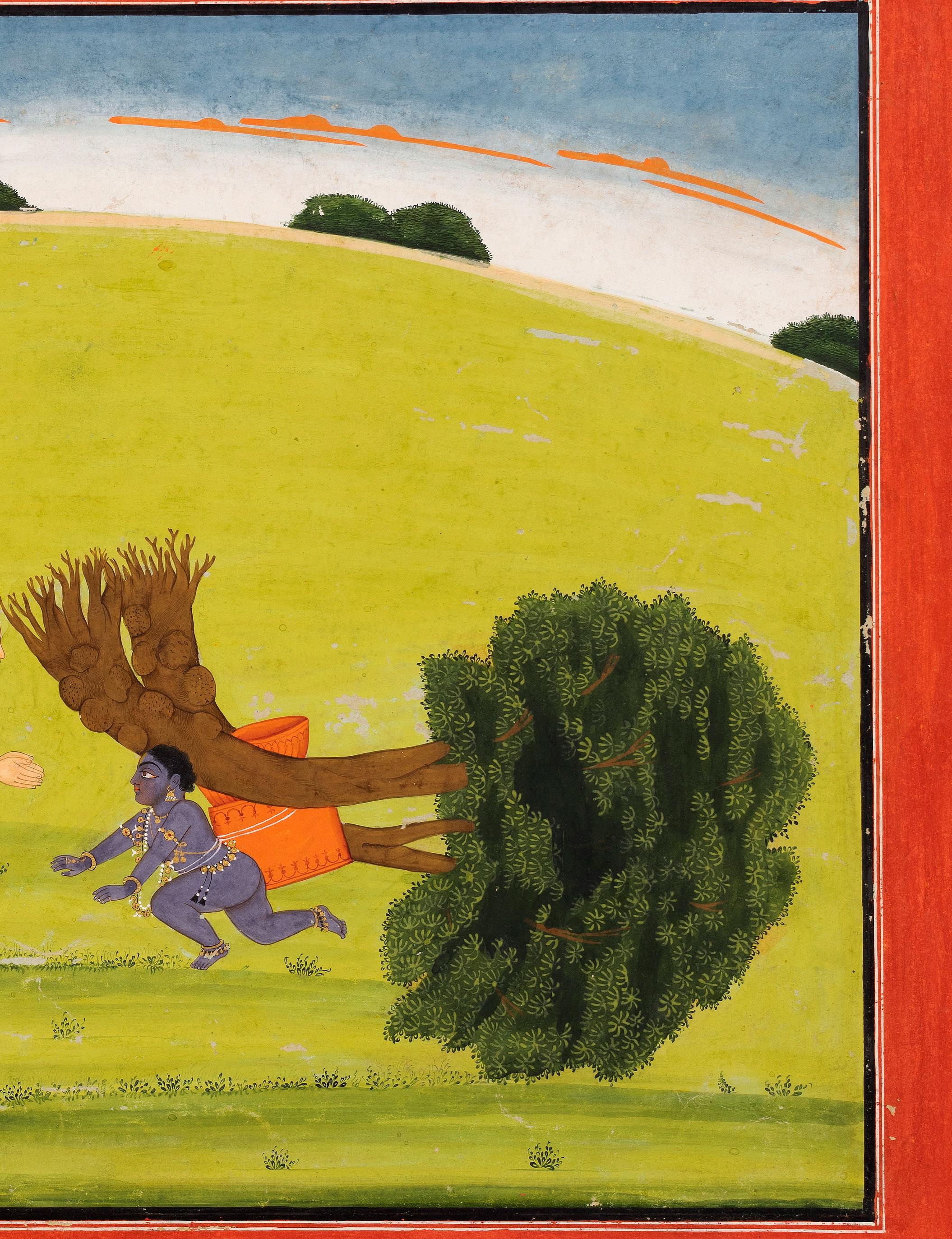

Illustration from the Bharany Ramayana Series: The Monkey Army Intruding Upon a Demon’s Cave

First generation after Nainsukh and Manaku

India, Punjab Hills, Kangra or Guler, 1775-1780 Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 ⅝ x 11 ⅝ in. (19.4 x 29.5 cm.)

Folio: 9 7/8 x 14 in. (25.1 x 35.6 cm.)

Provenance:

Collection of Dr Alma Latifi, CIE, OBE (1879-1959).

Sotheby’s New York, 5 December 1992, lot 163.

This folio originates from the Bharany Ramayana series, named after collector and dealer C.L. Bharany. The painting is attributed to the first-generation Kangra masters following Nainsukh and Manaku, earning it the moniker ‘second Guler Ramayana.’ Its lineage, tied to both artistry and collectors, elevates its status as a highly sought-after collectible.

The scene depicted, portrays a battle between monkey army troops and a demon within a cave. Sugriva, the benevolent monkey king of Kishkindha, witnessed Sita’s abduction and, exiled at the time, saw her throwing jewels into a cave, hoping to create a trail for Rama. The painting captures Sugriva confronting a demon in that cave, intending to inform Rama and Lakshmana of the incident.

The intricate scenery, marked by airbrushed trees and flying birds, conveys a sense of passing time. The foregrounding and backgrounding of flora and fauna enhance the overall artistic richness. The iconographic and stylistic representation of the Ramayana aligns with the ‘Tehri Garhwal’ Gita Govinda and the ‘Modi’ Bhagavad Purana. According to W.G. Archer, the series was commissioned by Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra’s mother for his wedding.

Other illustrations from the Bharany series are housed in esteemed institutions like the San Diego Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rietberg Museum, Philadelphia Museum, and Minneapolis Museum.

27

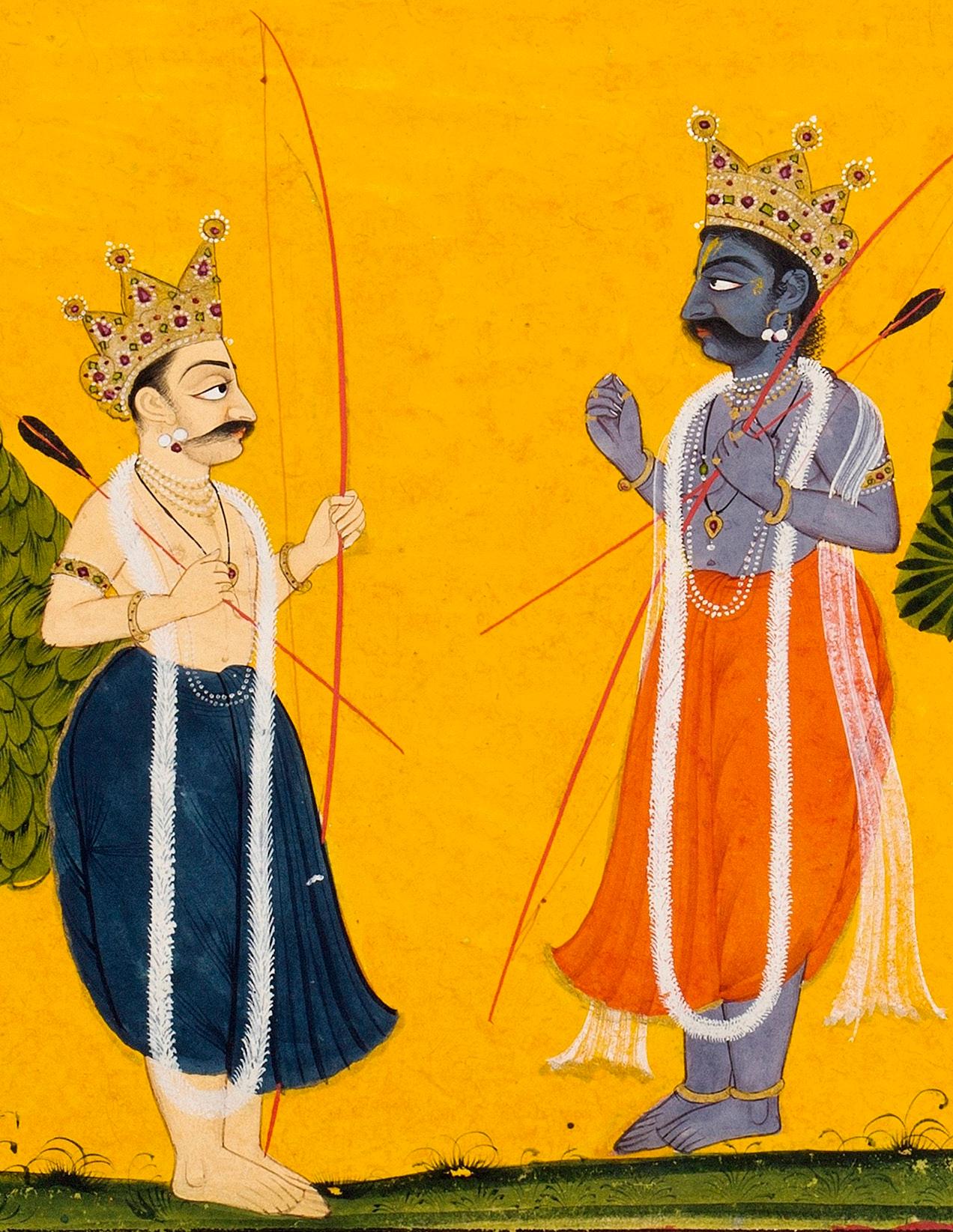

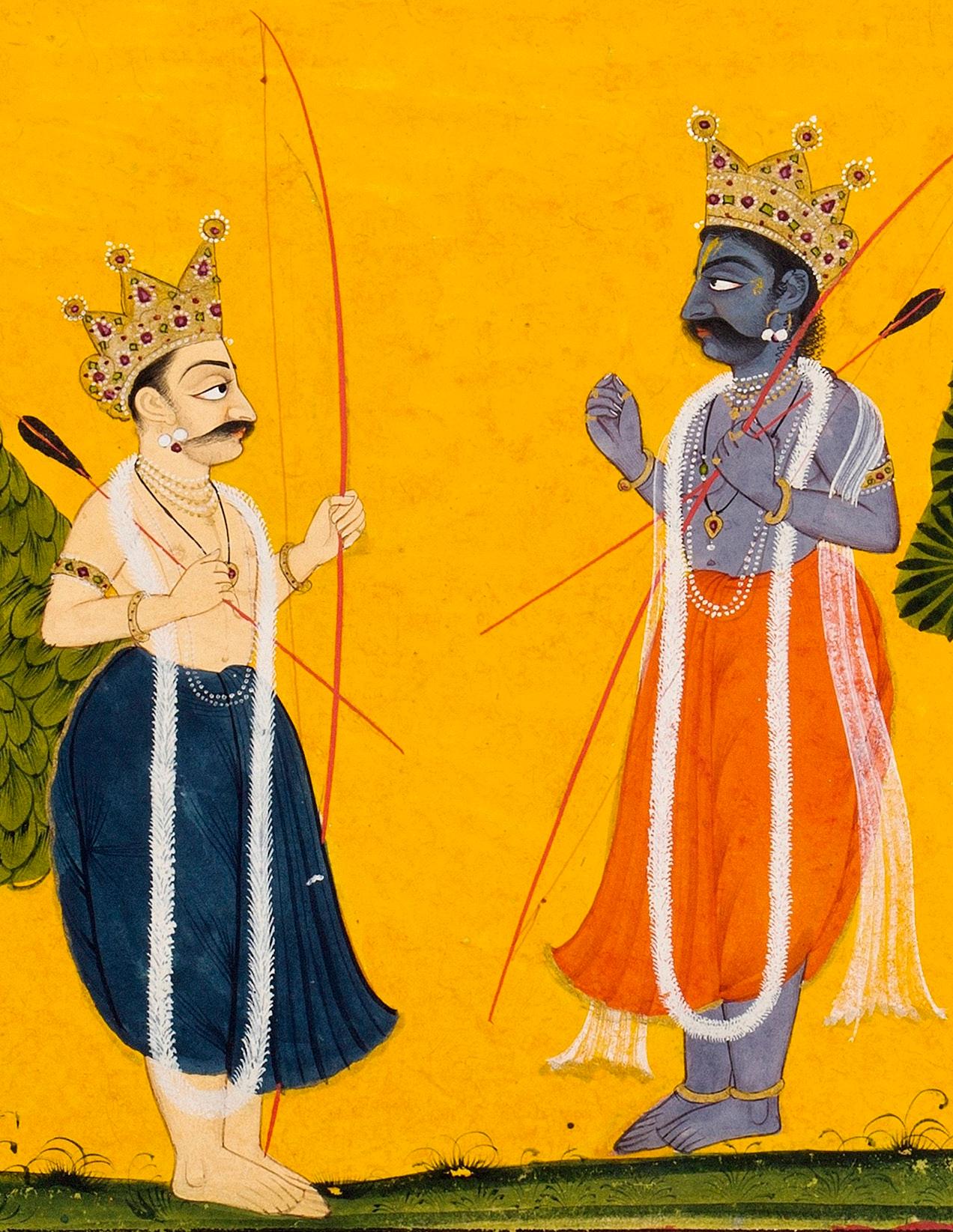

Illustration to the Ramayana: Rama and Lakshmana

Attributed to Pandit Seu

Basohli, circa 1730

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 ¼ x 12 ¼ in. (20.1 x 31.1 cm.)

Folio: 8 ½ x 12 ½ in. (21.6 x 31.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Collection of R. Hale, California, acquired by the family in the 1960s.

The present painting is attributed to the famous, yet elusive artist, Pandit Seu. The honorific title ‘Pandit’ probably denotes that the family was originally of the Brahamanical order. While it is speculated that he lived from 1680-1740, it is rare to find any dated or signed works by his hand, resulting in a small number of paintings attributed to him.

Pandit Seu was working at a time when the fundamentalist Mughal ruler Aurangzeb had disbanded his ateliers, forcing Mughal artists to search for patronage in Rajput kingdoms and simultaneously disburse their style into other regions. As this was happening, Pandit Seu traveled outside of Guler to the plains and made contact with Mughal artists who taught him their painting techniques. He brought these back to Guler and Basohli and is credited with aiding in the shift to a more formal style within the greater Pahari region.

In the present portrait of the Ramayana’s protagonists, this Mughal influence is apparent. The figures appear as strong individuals, assuming a space that belongs entirely to them rather than in an overlapping fashion typical of earlier Rajput painting. The face of each figure is unique, with Rama’s low eyes and his voluminous hair fully distinguished from Lakshmana’s clean hairline and downturned nose. Their flowing garments are highlighted by the stark, monochromatic yellow background characteristic of the Pahari tradition. This painting serves as a benchmark for the beginning of an exploration into depth and naturalism in the Pahari region.

28

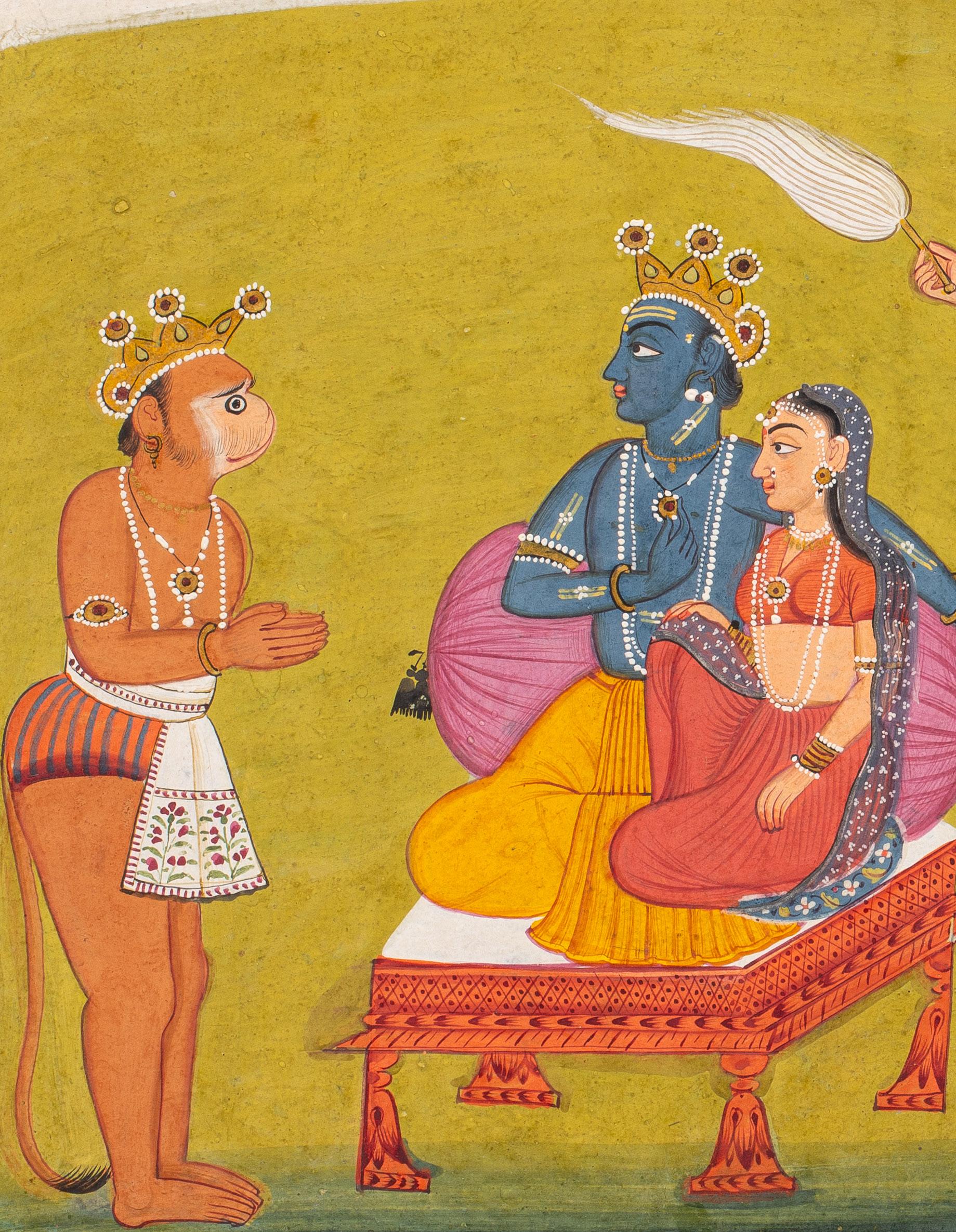

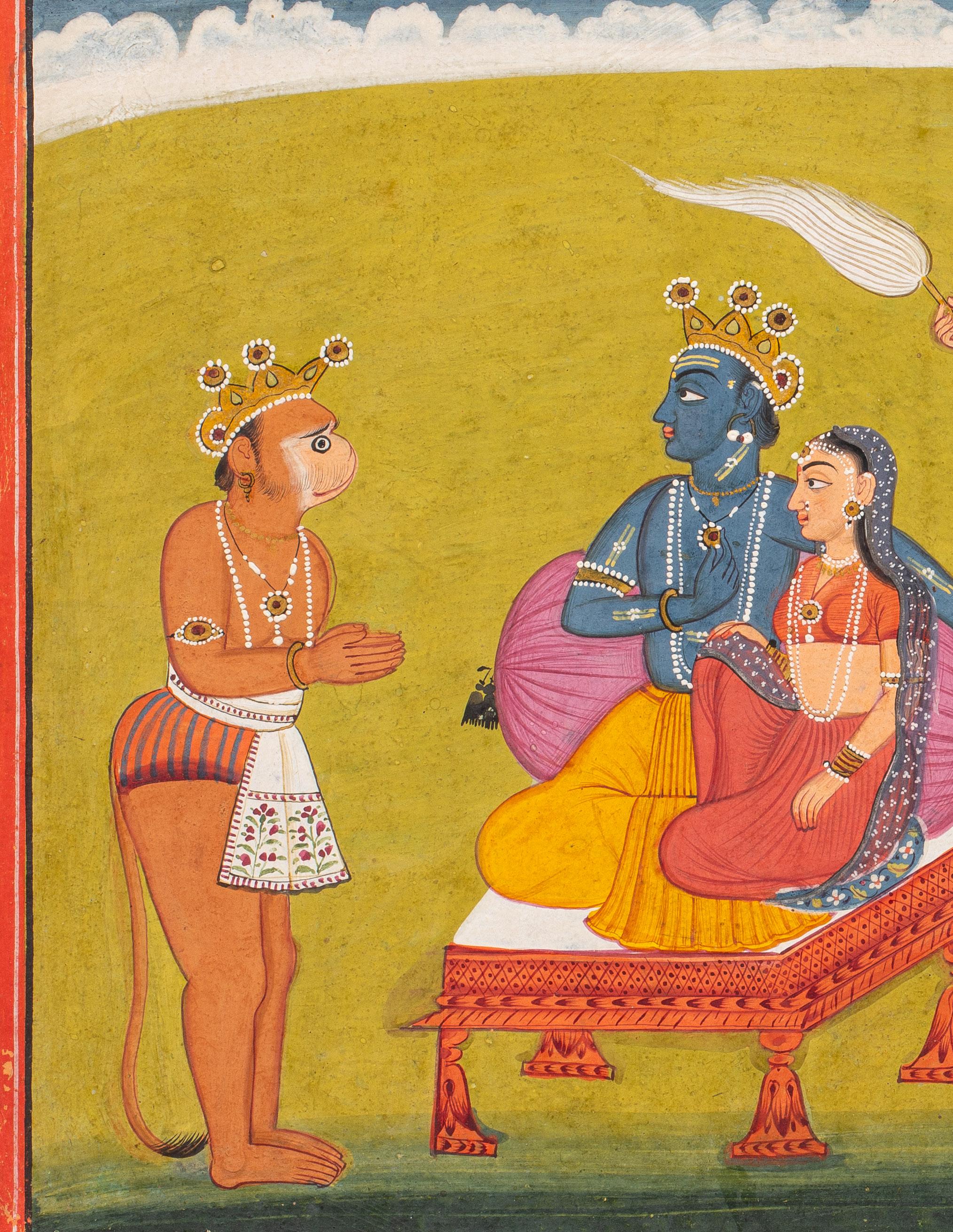

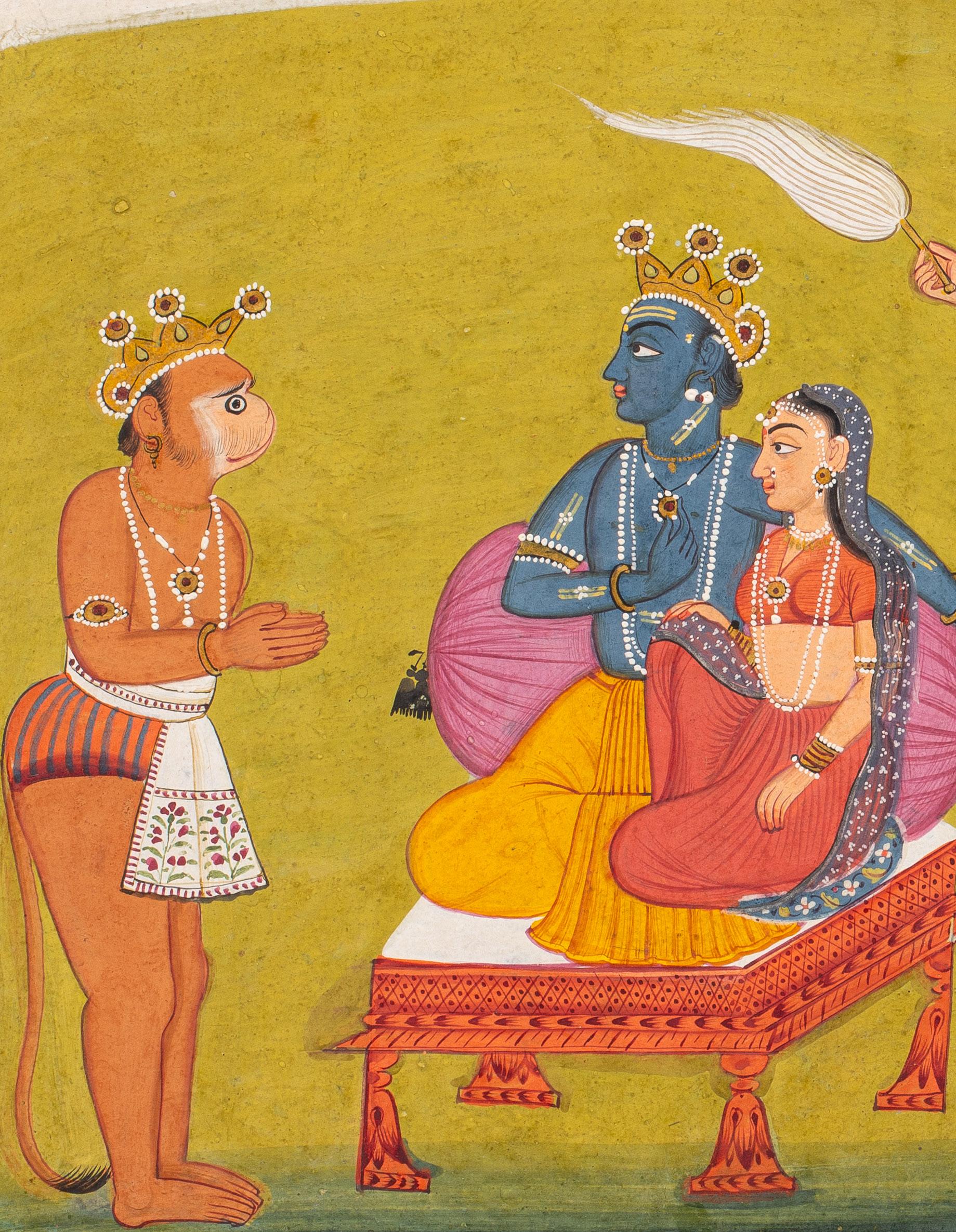

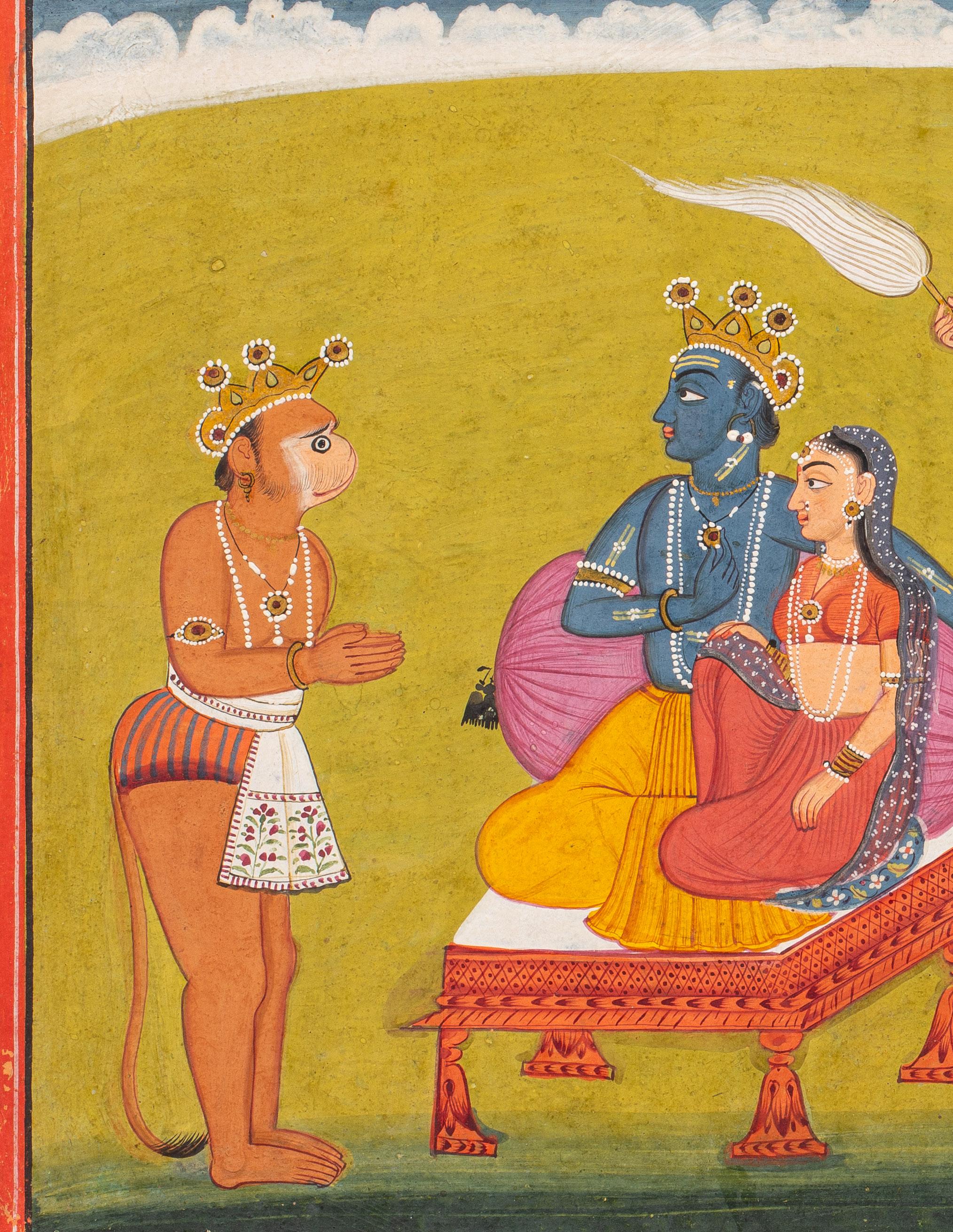

Illustration to the Ramayana:

Rama and Sita Enthroned

Basohli, circa 1730

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 ⅜ x 6 ⅜ in (23.8 x 16.2 cm)

Folio: 10 ½ in. x 7 ½ in ( 26.7 x 19.1 cm)

This painting depicts a pivotal episode from the Ramayana epic, portraying Rama’s triumphant return to his throne after vanquishing the demon king Ravana in Lanka. Positioned at the center, Rama and Sita are flanked by Hanuman on the left and Rama’s three brothers on the right. Lakshmana, holding a flying whisk (Chauri), stands prominently beside Rama, while Bharata and Shatrughna adopt similar reverential poses.

Characteristic of Pahari miniatures, the pointed crowns, fish-shaped eyes, receding foreheads, and robust facial features align with the Basohli idiom. The meticulous detailing of textiles in the artwork exemplifies the finesse typical of Pahari miniatures influenced from Mughal miniatures. As highlighted by M.S. Randhawa in Basohli Painting, the central thematic inspiration for Basohli painting is rooted in Vaishnavism (the worship of Vishnu). The devotional verses of sixteenthcentury saints and mystics found visual expression in seventeenth and eighteenth-century paintings.

A notable element in Basohli paintings is the portrayal of Rama in blue attire with a saffron dhoti, symbolizing his identity as the incarnation of Vishnu. The background captures an iconic Basohli feature – a landscape rendition with a distinctive blue strip representing the sky. Additionally, the deep red borders are a distinct, recurring characteristic in Basohli art.

For a comparable artwork with the same subject matter, refer to an earlier piece from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (SL.23.2019.1.1).

29

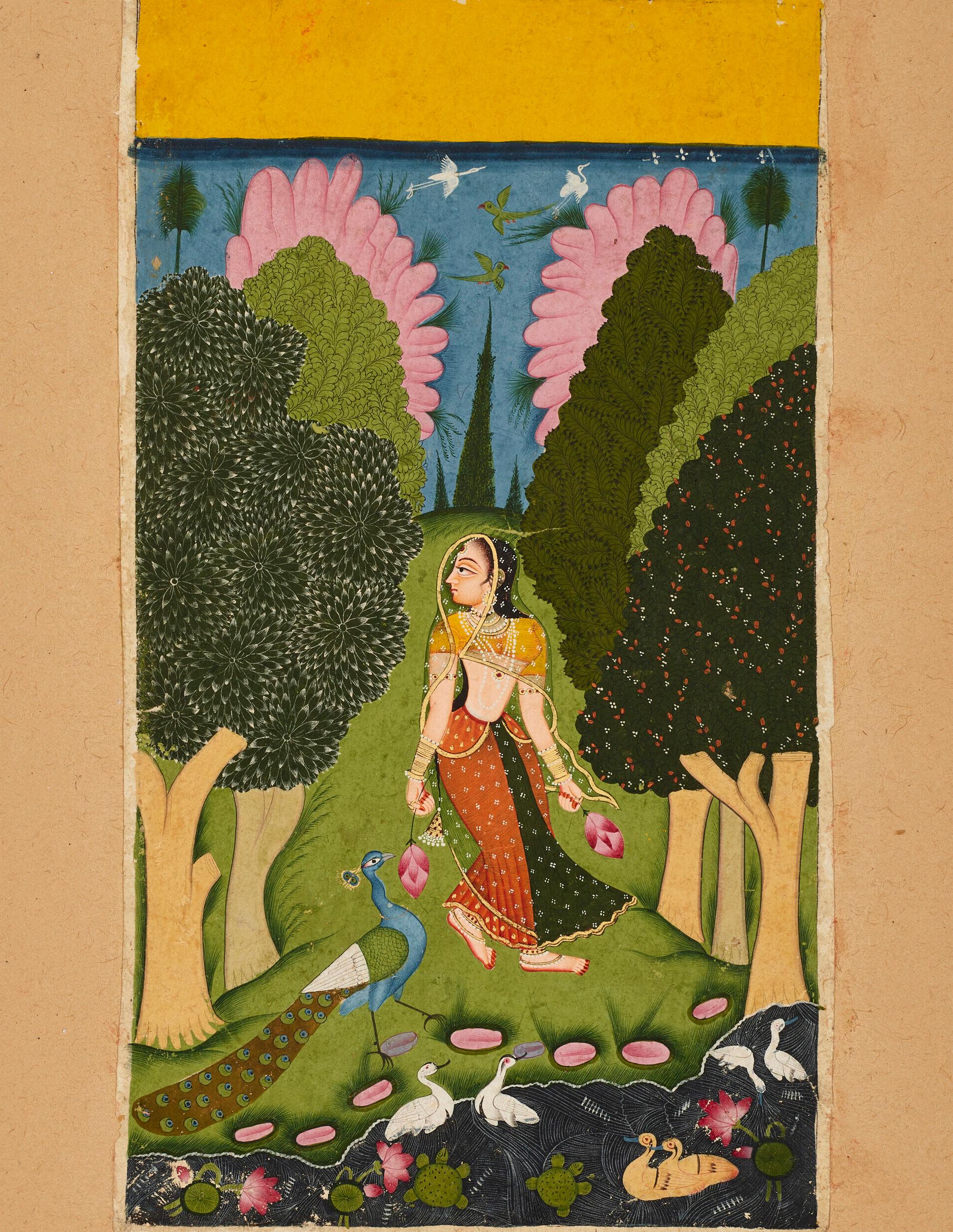

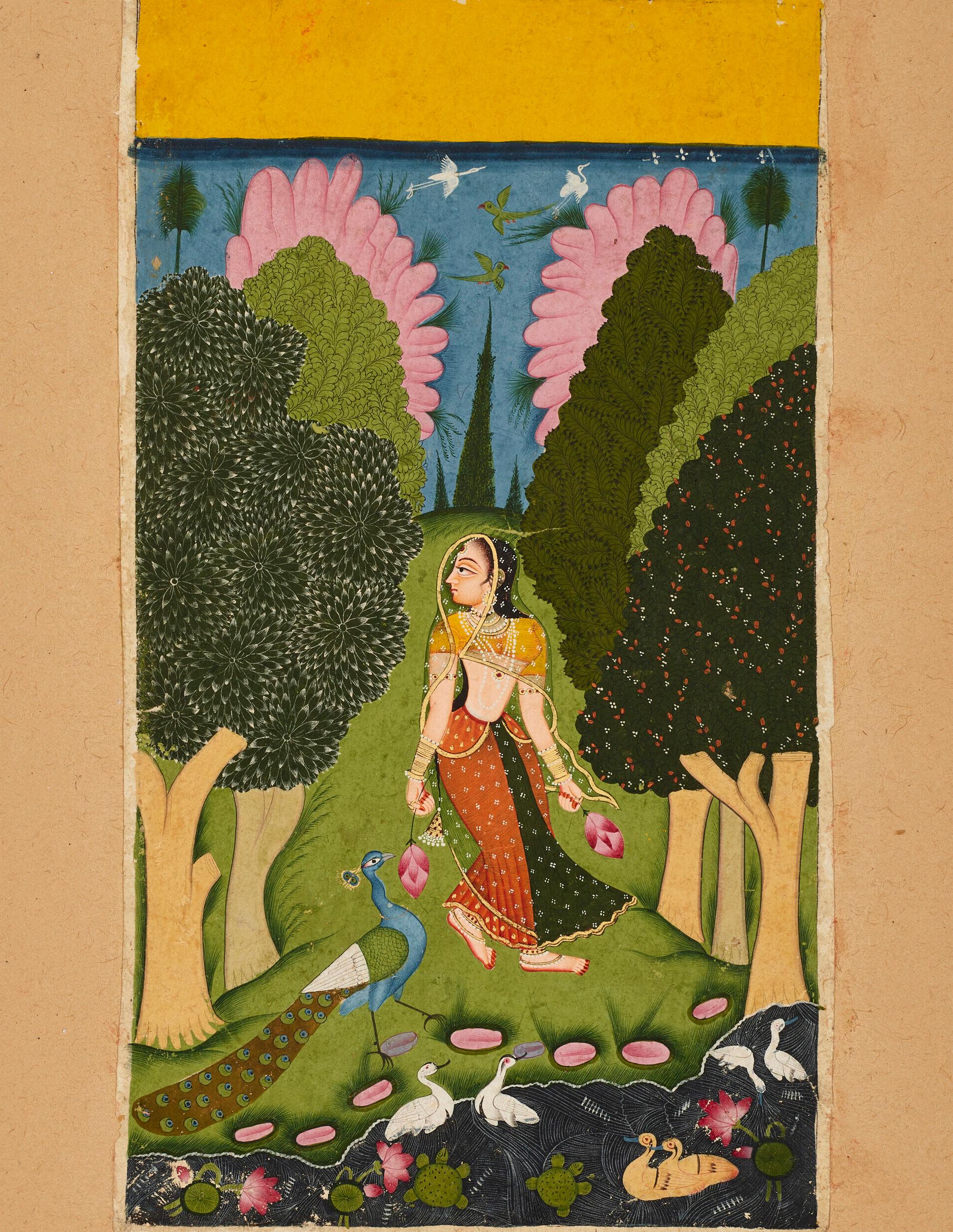

Leaf from a Gita Govinda series: Radha Vents her Frustrations

First generation after Nainsukh

Kangra, circa 1775 - 1780

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 7 x 10 ⅝ in. (17 x 27 cm)

Provenance:

The Collection of Françoise et Claude Bourelier. Artcurial, 4 November 2014, lot 228.

Sheltered within the verdant foliage of a grove of vakula and tamala trees, Radha appears garbed in a semitransparent orhani composed of mute colors. The ghaghra skirt around her waist cascades into gentle folds and a brief bodice exposes her bare midriff. Paramount attention to detail can be seen in the diaphanous materials of her layered garments as well as her intricate jewelry. Copious but not gaudy, she is adorned with gold, emeralds, and pearls. Equal attention is paid to the rendering of her confidant, who stands beside her on the Yamuna river bank as they discuss her beloved, Krishna.

Radha’s face, as well as that of her companion, is of “porcelain delicacy,” rounded but in such a manner as to not be “fleshy.” Her features are pronounced and sharp, her lips small (an attractive quality of the time), eyebrows gently arched, eyes gazing soft yet discerningly. “Radha’s body is young and lissome; the limbs tender, the breasts full, hands and feet delicate.” (Goswamy & Fischer, pg 315). Her stance is relaxed and natural, a reflection of her sweet countenance.

The setting is established with meticulous care. The small rises of the terrain and undulating ground all give a feeling of vast space and openness, but in such a way that attention is not drawn to wander from the foreground in which Radha and her companion are engaged in discussion. The delicacy and naturalism apparent in the rendering of nature imbues the scene with a fullness that conveys the hand of a master artist.

This folio comes from a Gita Govinda series that describes the courtship of Krishna and Radha as told by the poet Jayadeva. Through Krishna and Radha,

Jayadeva evokes the fullness of love, filled with passion and longing as well as pride and jealousy. Serving as an allegory for the soul's longing to unite with the divine, Krishna and Radha’s love story is at its heart “the tempestuous process of emotional – and spiritual struggle – for grace." D. Mason, Intimate Worlds, Philadelphia, 2001, p. 192.

For other paintings from this series see Joseph M. Dye III, The Arts of India, Virginia, 2001, no. 151, p. 350; D. Mason, Intimate Worlds, Philadelphia, 2001, no. 82 & 83, pp. 192-194; W. G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, vol. II, 1972, nos. 33(i) – 33(vii); B. N. Goswamy and E. Fischer, Pahari Masters, Zurich, 1992, nos. 130 – 137, pp. 320 – 331.

30

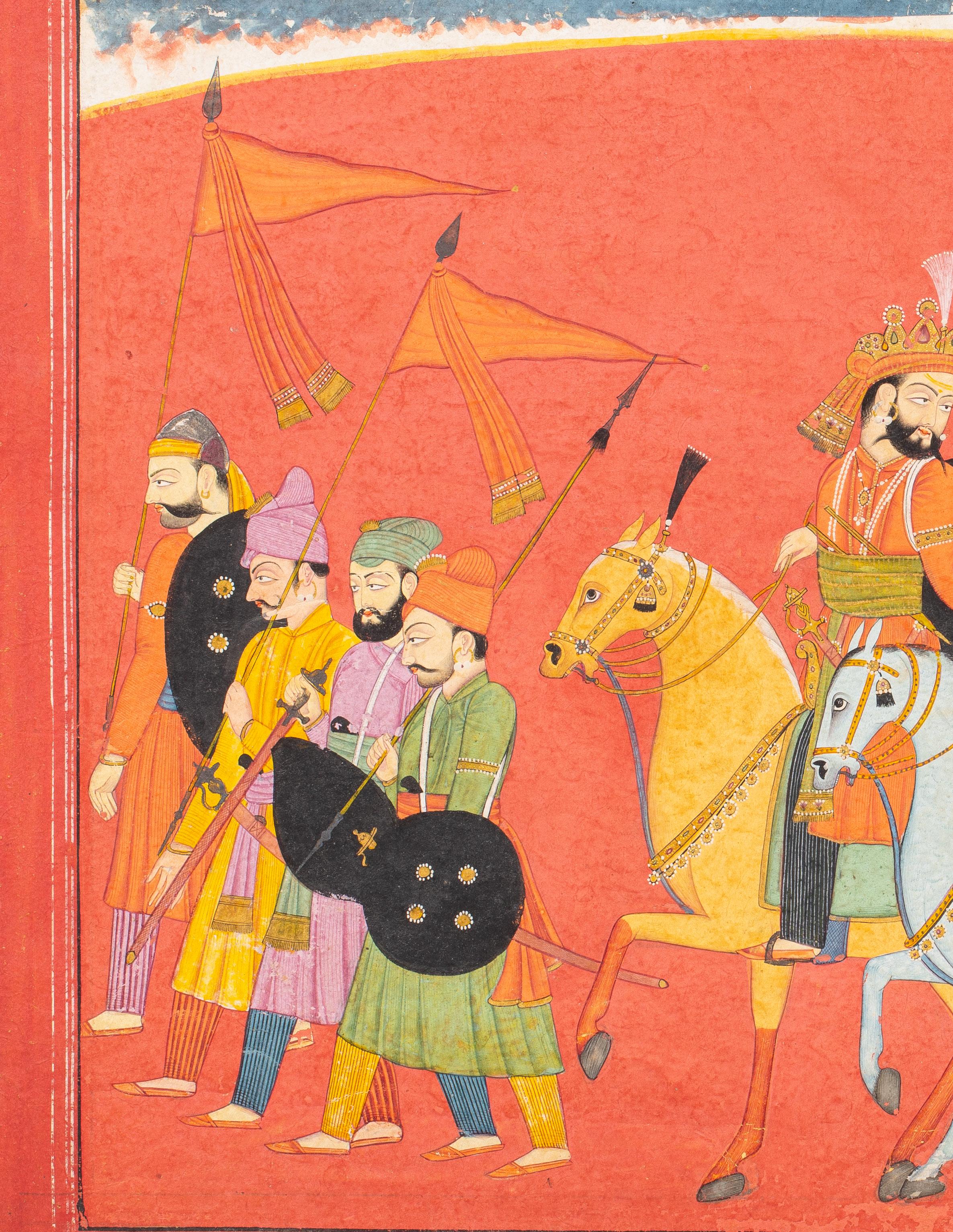

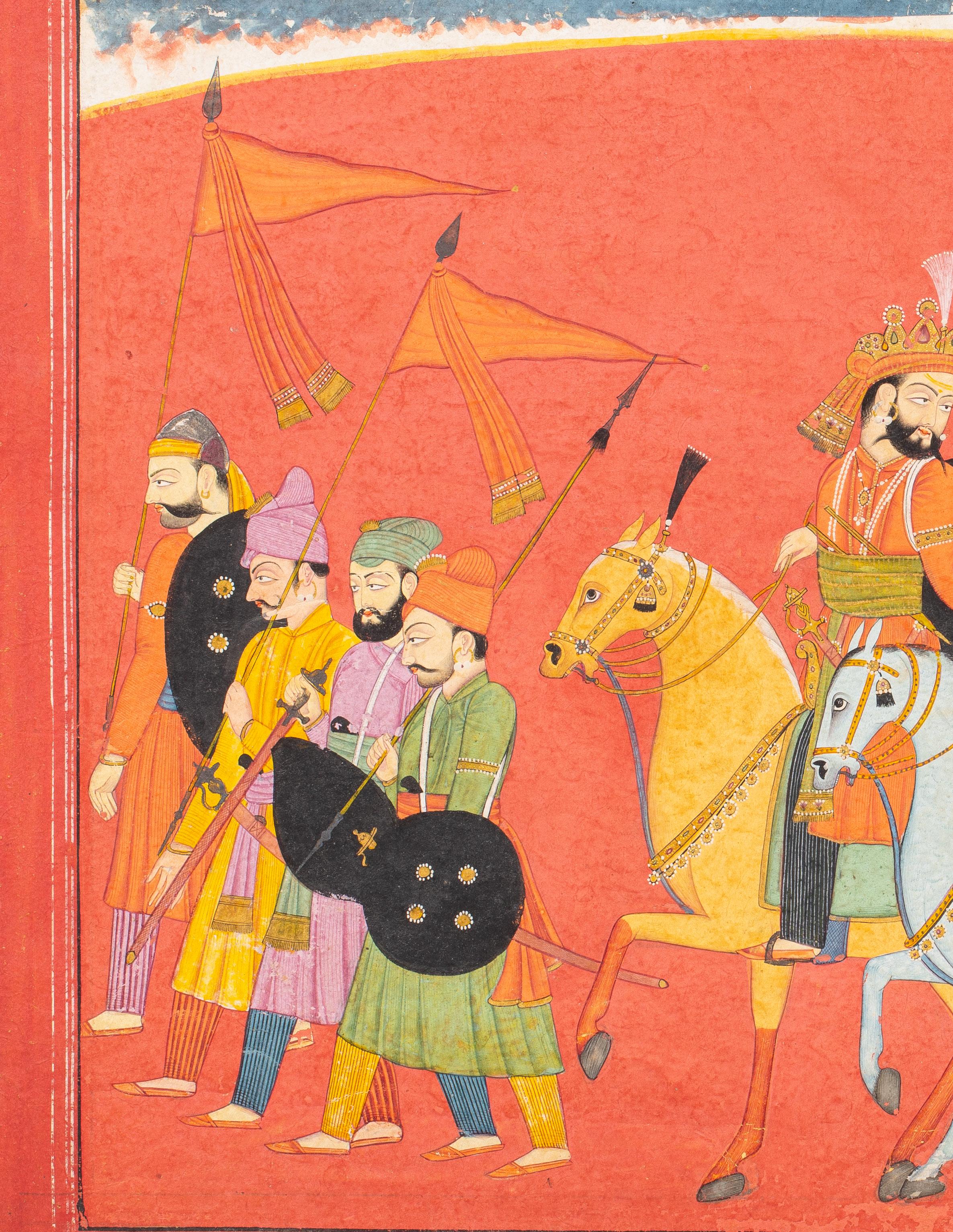

Illustration from the Bhagavata Purana:

Shishupal and his Retinue

Punjabi Hills, Garhwal, circa 1775

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

11 ⅜ x 8 ½ in. (28.8925 x 21.59 cm.)

Published:

Veronica Ions, Indian Mythology, London and New York: Hamlyn (1967), p. 70.

Mukandi Lal, Garhwal Painting, India: Government Ministry of Information (1968), pp. 88 – 89.

Provenance:

Arthur L. Funk Collection acquired January 2nd, 1970.

This scene from the Bhagavata Purana depicts princess Rukmini’s eldest brother Rukma welcoming Shishupal’s retinue and leading them to Kundinapura. Shishupala and his companion are astride gray mares whereas Rukma is astride an almond-coloured horse.

Kundinapura is the capital of the Vidarbha kingdom ruled by King Bhishmaka, the father of prince Rukma and princess Rukmini.

Shishupala, the son of King Damaghosha and Srutashubha (the sister of Vasudeva and Kunti), was the king of the Chedi kingdom.

The red border conveys the fact that the painting is a part of a larger set of similar Bhagavata Purana paintings.

31

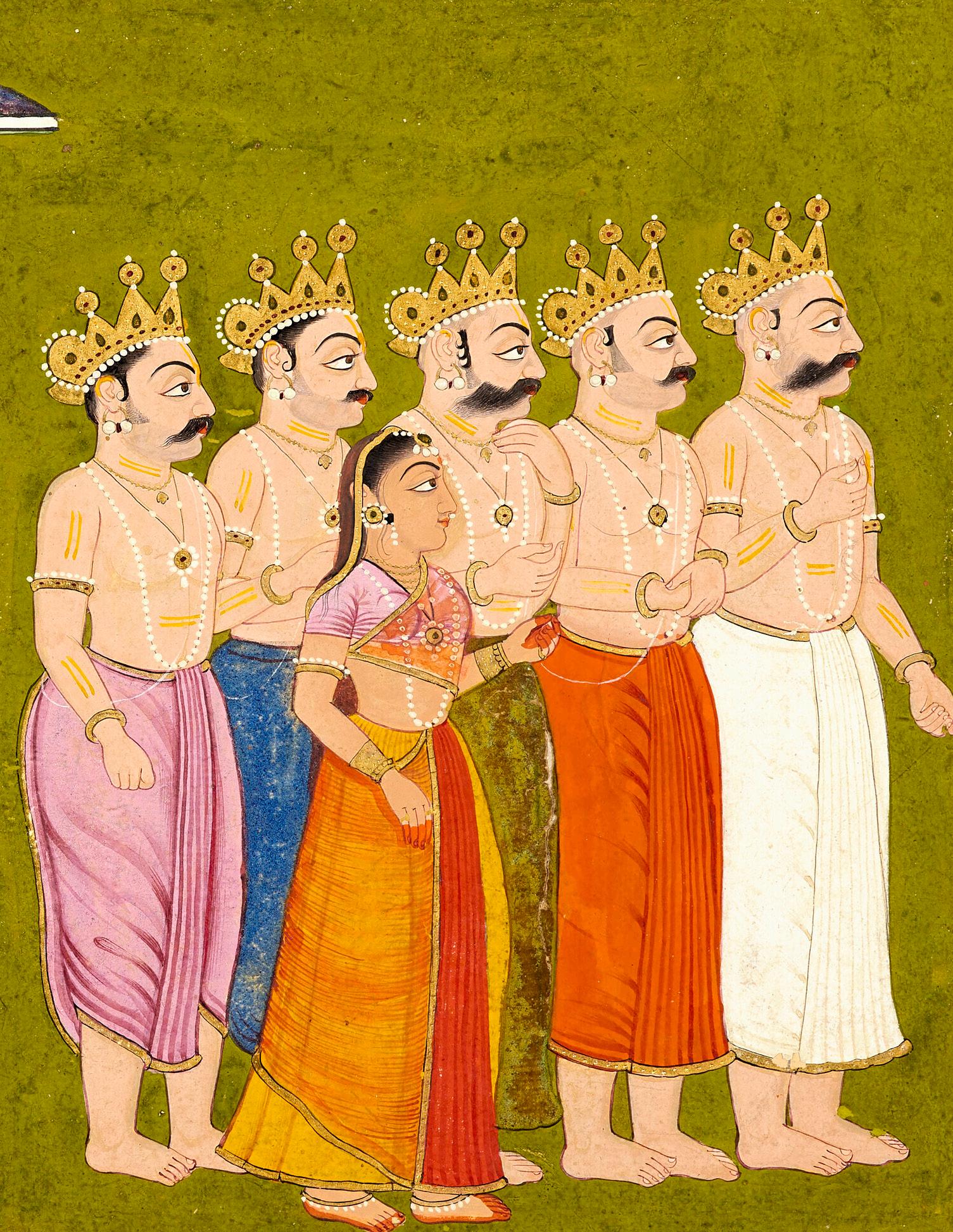

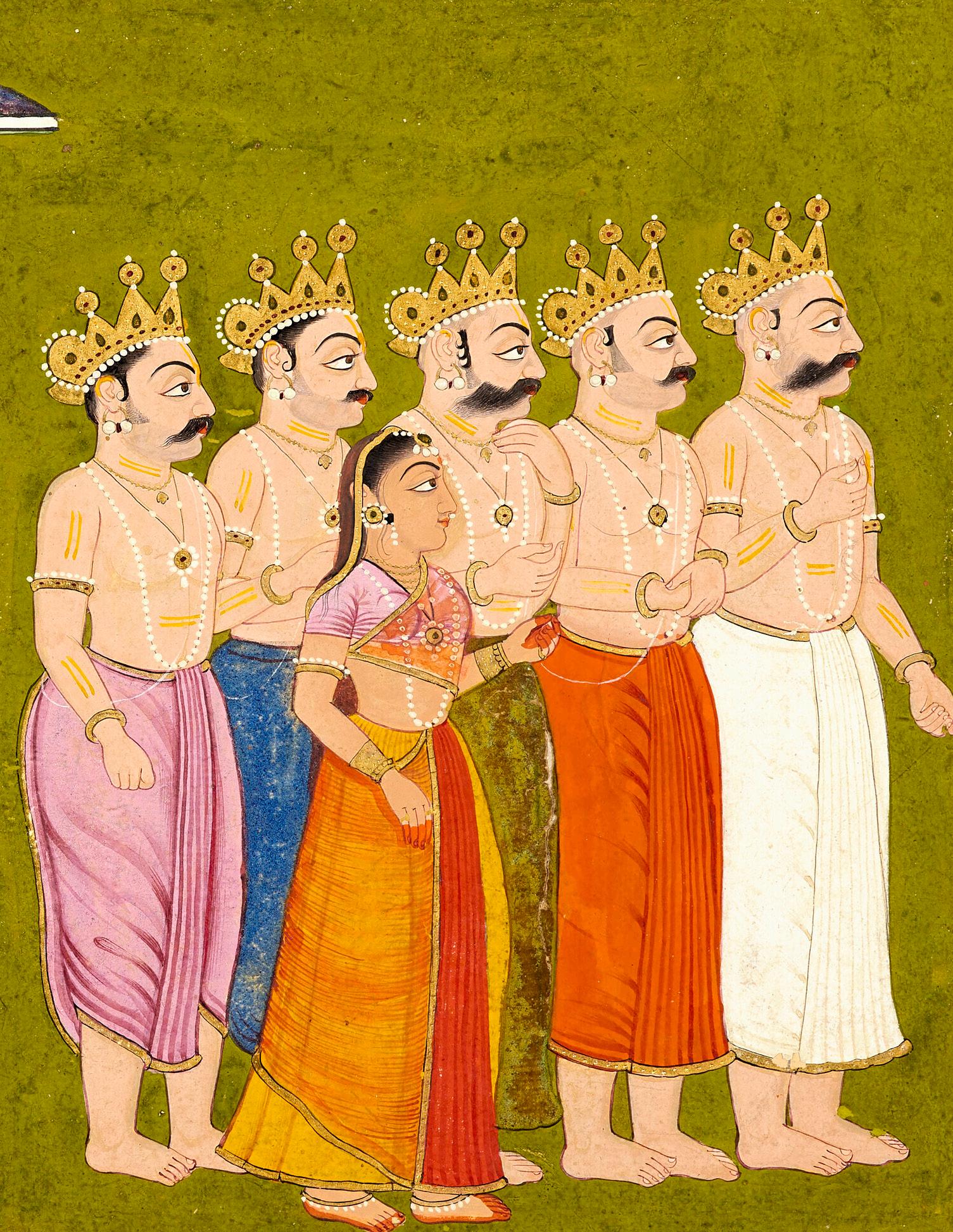

Illustration from Bhagavata Purana:

Draupadi and Her Five Husbands Leave After Visiting a Prince Attributed to Manaku

India, Punjab Hills, Basholi, circa 1740

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 6 ¼ x 10 ½ in. (15.9 x 26.6 cm.)

Folio: 7 3/4 x 12 ¼ in. (19.6 x 31.1 cm.)

Published:

B.N. Goswamy, Manaku of Guler: The Life and Work of another great Indian Painter from the small Hill State, New Delhi, 2017, pp. 447

Exhibited:

Doris Wiener Gallery, New York, “Indian Miniature Painting,” 16 November - 31 December 1974, no. 19.

Carlton Rochell Asian Art, New York, “Classical Indian Paintings,” 13-20 March, 2015, no. 24.

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 20 March 2012, Lot 215.

Set in an artistically devised rectangular frame, this painting alludes to the strong visual narration abilities of the renowned artist of Guler, Manaku – the elder brother of Nainsukh. This visual illustration of the Panchodash Adhyay (fifteenth verse) of the first Skandha (section) from the Maha Bhagavat Purana epic narrates the episode of the Pandavas handing over the kingdom to King Parikshit. King Parikshit was the son of Prince Abhimanyu (the grandson of the great Pandava prince Arjuna) and his wife Princess Uttara.

It is said that once Krishna left his worldly body, the Pandavas could not come to terms with social evils and sins that engulfed the world just before the current age of Kali-yug. They renounced their princely lives and left for heavenly abode in the mountains. It was the eldest brother Yudhishtira’s devout choice and all the other brothers along with Draupadi followed his penchant.

The orientation of the gaze of all the characters in the same (right) direction underscores the pivotal moment of pause that occurred when the Pandava princes renounced the kingdom and the Grihastha (household) life in totality. The royal blue and moss green backgrounds likely stand as larger metaphors of worldly and spiritual realms, highlighting Manaku’s masterful use of empty space to evoke certain moods. Draupadi as the sole feminine figure in the frame pulls in the viewer with the slender and petite delineation of her form contrasting the very stout and bare-chested figures of her husbands. This vertical division of space also enlivens the painting by creating a sense of the passage of time. A captivating red border around the painting can be seen as a common trait associated with all paintings from the present Bhagavat Purana series. Dr. Goswamy has incorporated this painting in his seminal work, Manaku of Guler: The Life and Work of another great Indian Painter from a small Hill State which is a repertoire extolling the life and work of this greatly abled artist from the early 18th century.

32

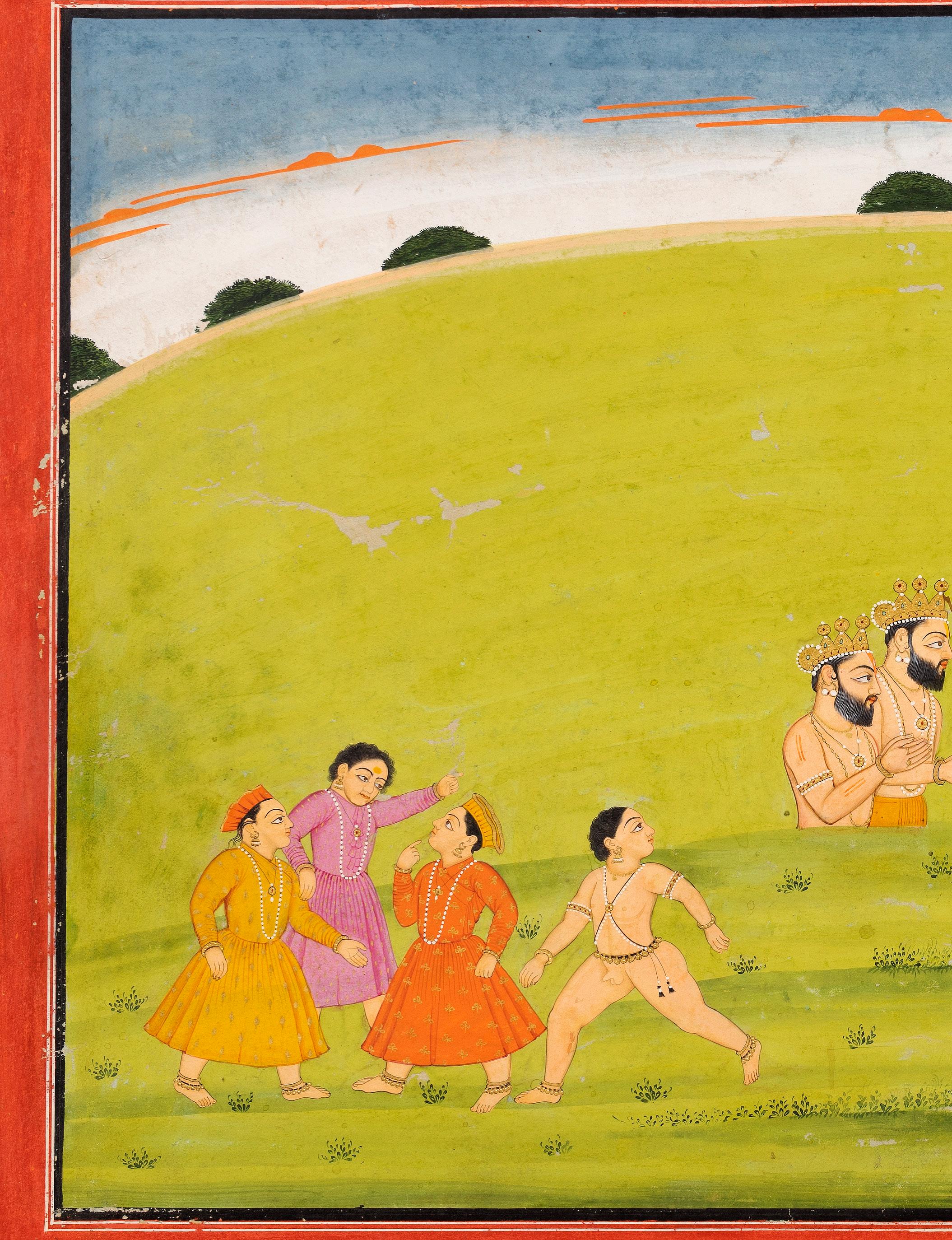

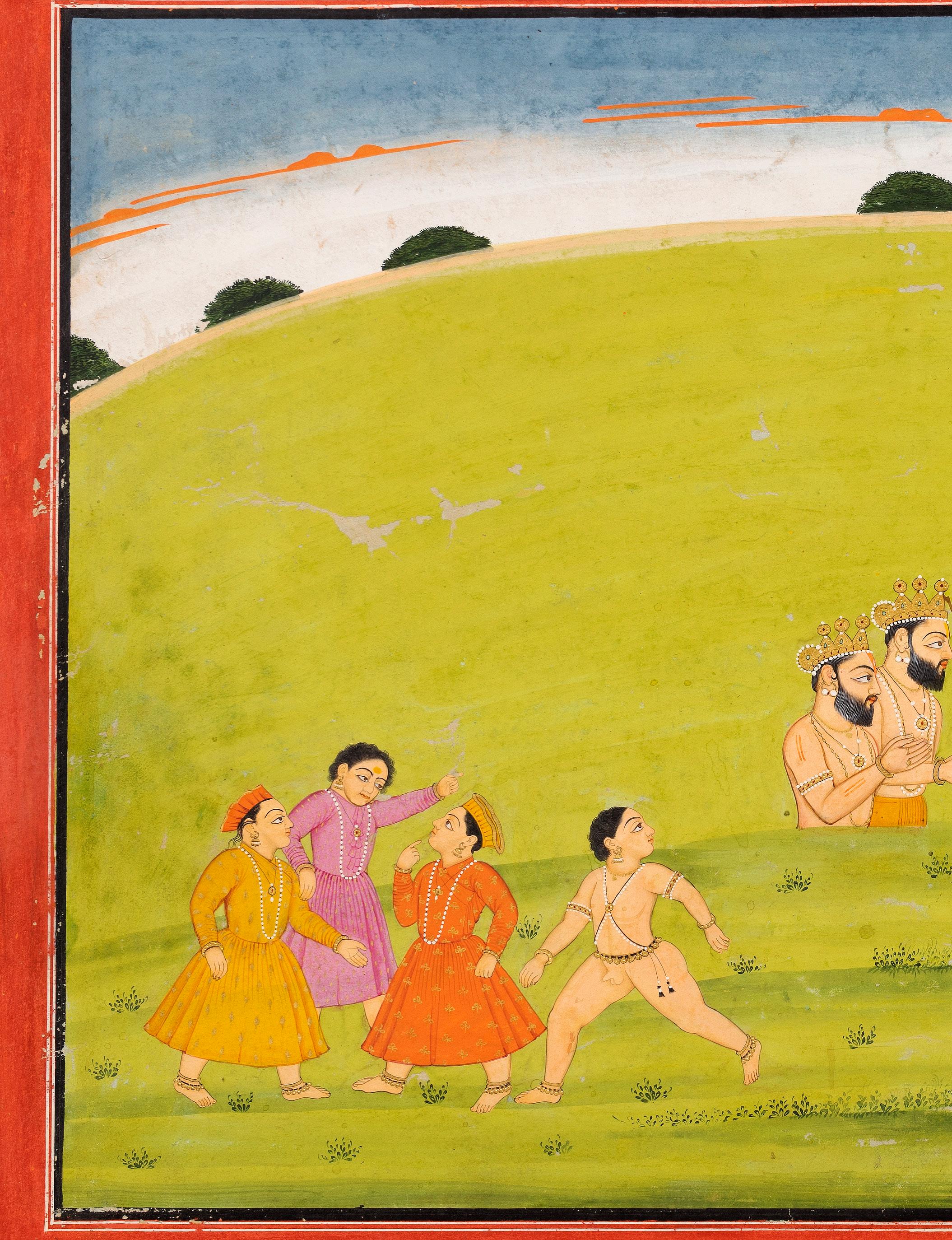

Illustration to the ‘Large’ Guler-Basohli Bhagavata Purana: The Liberation of Nalakuvara and Manigrivaa

Attributed to Manaku

Guler-Basohli, circa 1760-1765

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 ⅛ x 13 ¼ in. (23.3 x 33.5 cm.)

Folio: 11 ¼ x 16 in. (28.9 x 41 cm.)

Provenance:

The collection of Brendan Garry (d. 16 September 2011).

The collection of Siva Swaminathan (d. 26 March 2014).

This painting depicts a scene from the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana, which captures young Krishna’s penchant for mischief. After being caught repeatedly trying to steal butter by his foster mother, Yasodha, she tied him to a wooden mortar to keep him from trouble. Many years prior to this, two yakshas, Nalakuvara and Manigriva (sons of Kubera), were cursed for their pride and bound in the form of two arjuna trees. Through his omniscience, Krishna knew the arjuna trees contained the souls of these yakshas—carrying the mortar on his back and wedging it between the trees, the young hero used his great strength to uproot them, thus freeing the two brothers from their bondage. The yakshas are shown crowned in the center of the painting, offering praise to Krishna to express their gratitude.

The present illustration comes from a series dated to 1760–1765, commonly known as the ‘Large’ GulerBasohli Bhagavata Purana, or the ‘Fifth’ Guler-Basohli Bhagavata Purana. This series is known for its use of broad landscapes with few figures, exemplary of a transitional Basohli style. Each painting in the series has an identifying inscription on the reverse in gurmukhi and nagari scripts—the present painting is labeled ‘Leaf 35’ in gurmukhi, and inscribed ‘Bhagavata Purana, 10th Chapter, 10th book’ in Sanskrit. The leaves have since been dispersed throughout the world, some of which can now be found in the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Archer Collection (see W.G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, London, 1973; Visions of Courtly India, London and New York, 1976, no. 8, p. 15; and W.G. Archer and Edwin Binney 3rd, Rajput Miniatures from the Collection of Edwin Binney 3rd, Portland 1968, nos. 55a and 55b, pp. 74–75 for other paintings).

This painting was likely executed by the master Manaku, older brother of Nainsukh, even if he was not responsible for completing the entire series. Manaku has been named as the illustrating artist for a Gita Govinda series completed in the 1730s, as well as the ‘Small’ Guler Bhagavata Purana completed between 1740 and 1750. Similarities between works in both of these earlier series to the 1760s Bhagavata Purana indicate that Manaku had a part in completing multiple pieces from the later series.

Compare the yakshas in the present work to The Sage Kardama Renounces the World, from the ‘Small’ Guler Bhagavata Purana in the collection of the Lahore Museum (see B. N. Goswamy, Manaku of Guler, New Delhi, 2017, p.405, no. B35). The same careful rendering of facial hair and ornate jewelry support the claim that Manaku was the author of both. In addition, realistic detail is ascribed to the trees across Manaku’s known oeuvre, replicated in the arjuna trees shown here.

While some scholars argue that this later Bhagavata Purana was illustrated by Fattu, son of Manaku, it is clear that the series was drawn by a number of different hands. Since these series were typically completed in chronological order, following the progression of the text, the present example would have been executed earlier than many others within the series, bolstering the plausibility that this painting was indeed drawn by the hand of Manaku.

33

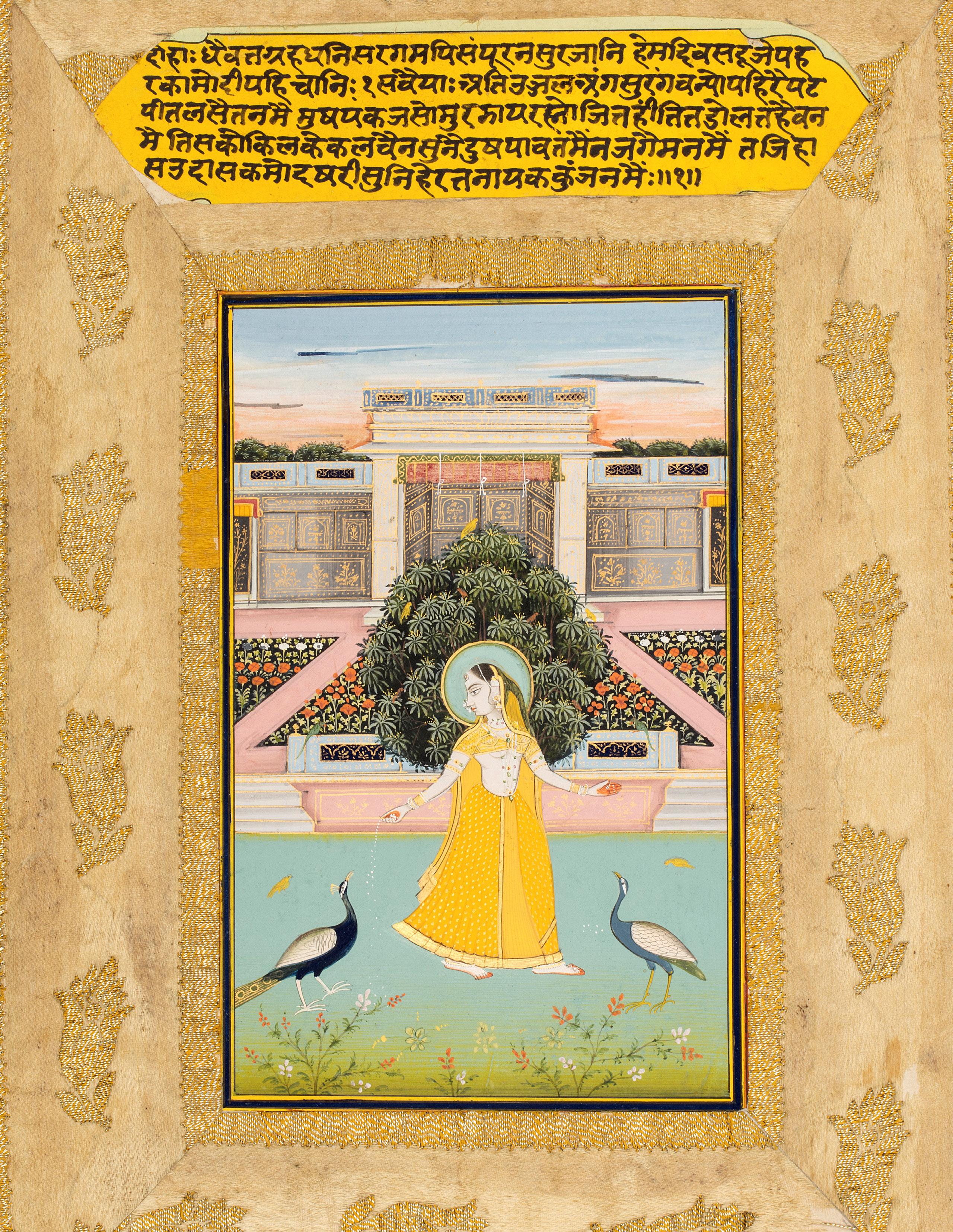

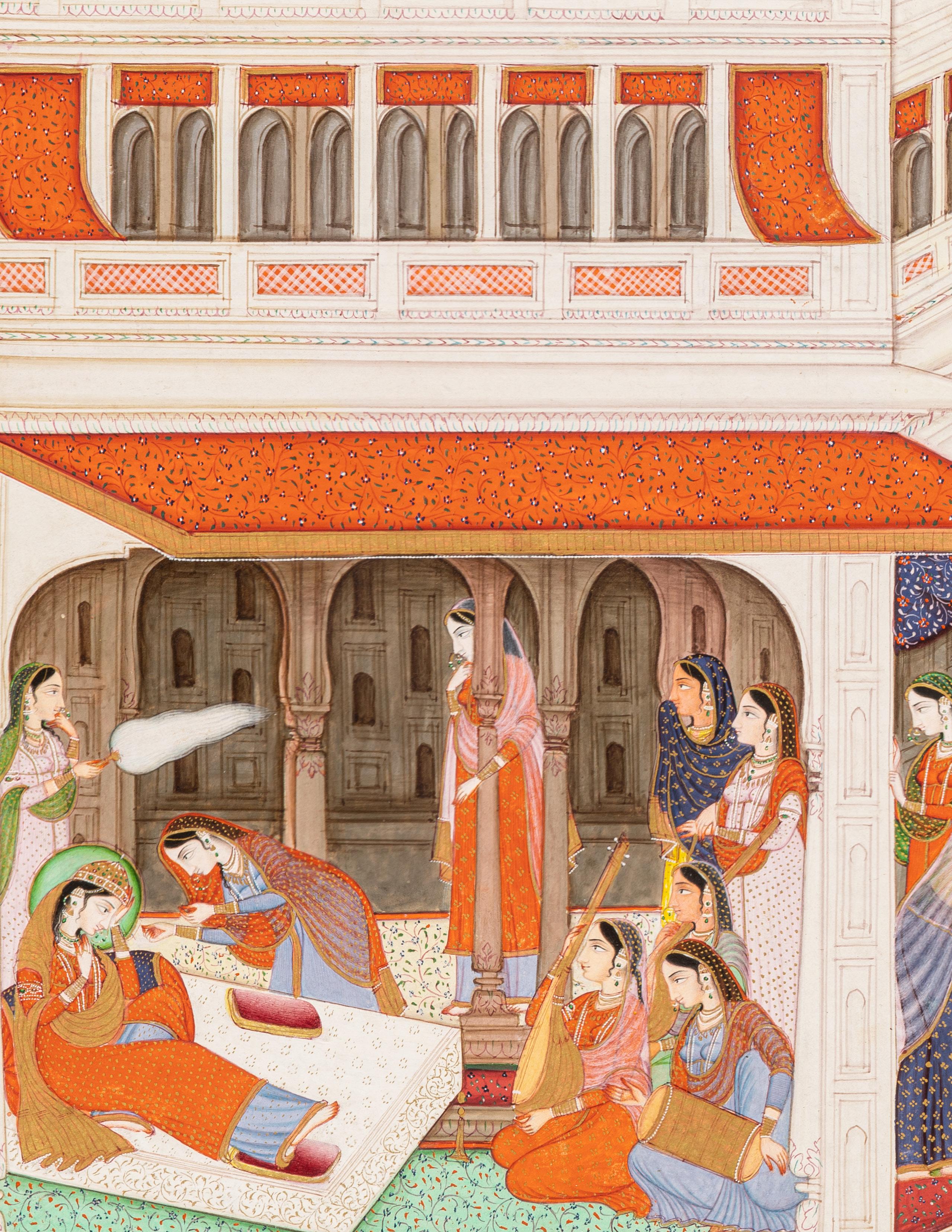

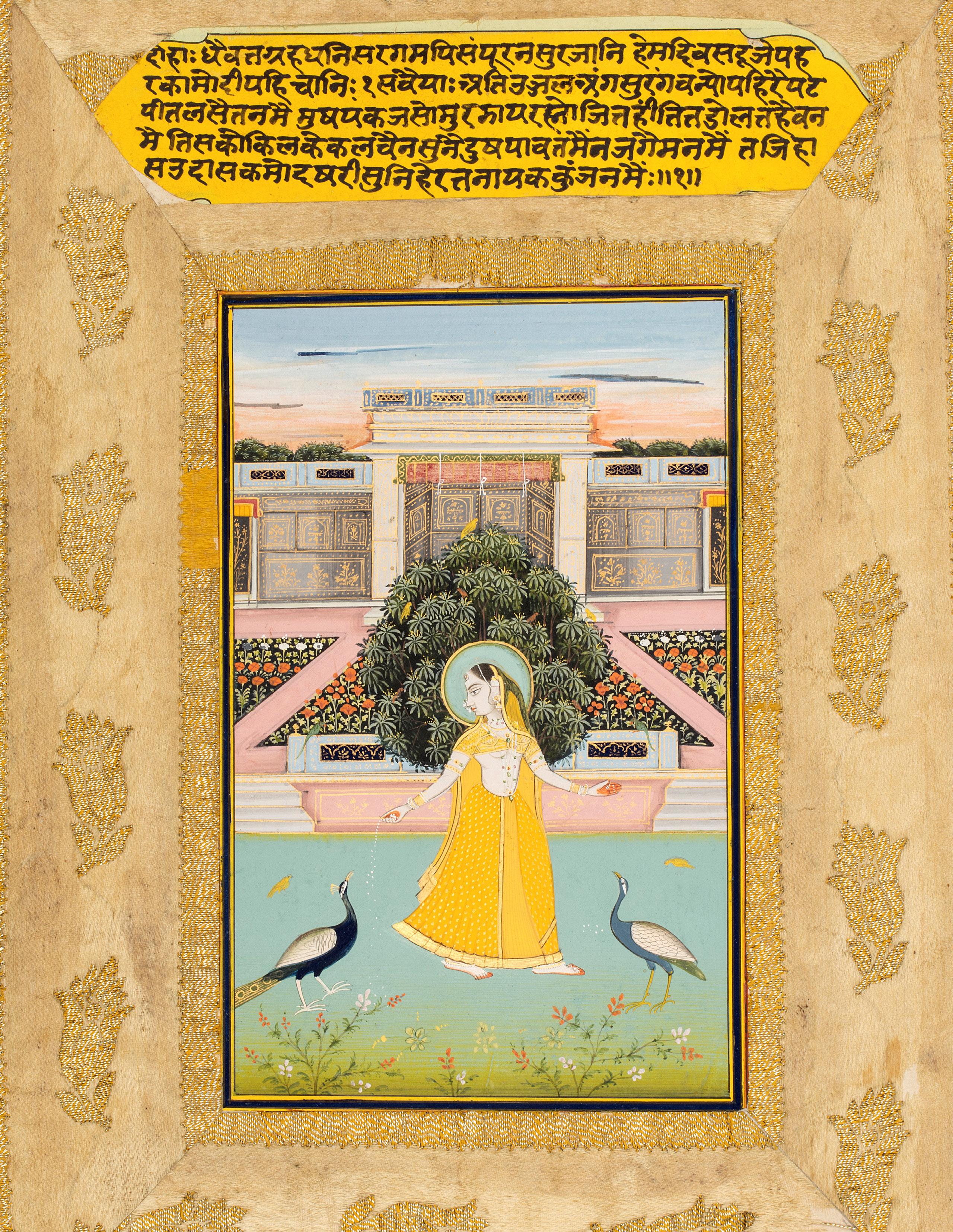

Illustration to the Ashta Nayika: Abhisandhita

Kangra, late 19th century Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 ¼ x 11 7/8 in. (21 x 30.2 cm.)

Folio: 10 ½ x 14 ⅛ in. (26.7 x 35.9 cm.)

Abhisandhita Nayika, the dejected lover, is she who is estranged by a quarrel. Overcome with pride, this heroine rejects her beloved and disregards his devotion despite his apologies. Unable to soften her anger, he departs. Her indifference is but a facade, though, and in his absence she burns with remorse. The result is vipralambha mana, love in separation on account of pride, representing the intrusion of the ego between the soul and Brahman. Hindi poet Keshav Das describes mana as the feeling of pride incited by love. The distraught nayika sits in the bottom left corner, her face full of sorrow. Her sakhi consoles her while musicians attempt to comfort her with soothing music. Her beloved appears with his back turned at the opposite side of the painting, solemnly leaving the palace. Much of the composition features complex architectural elements, including a lush courtyard housing detailed foliage of various shades of green. Such verdant greenery and precise architectural detail are characteristic of nineteenth-century Kangra painting, as is the pastel palette and soft, clean lines.

Depictions of love in all its forms were popular subjects in Kangra painting. These artists incorporated many fine aspects of Mughal painting, producing a style characterized by brilliant colors, rhythmic line drawings, and extreme attention to detail. The current example leaves the viewer not only with a sense of the impeccable artistry of the Kangra painters but also with an overwhelming feeling of romance and all the trials that come with it. For another depiction of this subject from late nineteenth century Kangra, see the Abhisandhita Nayika in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (acc. IS.40-1949).

34

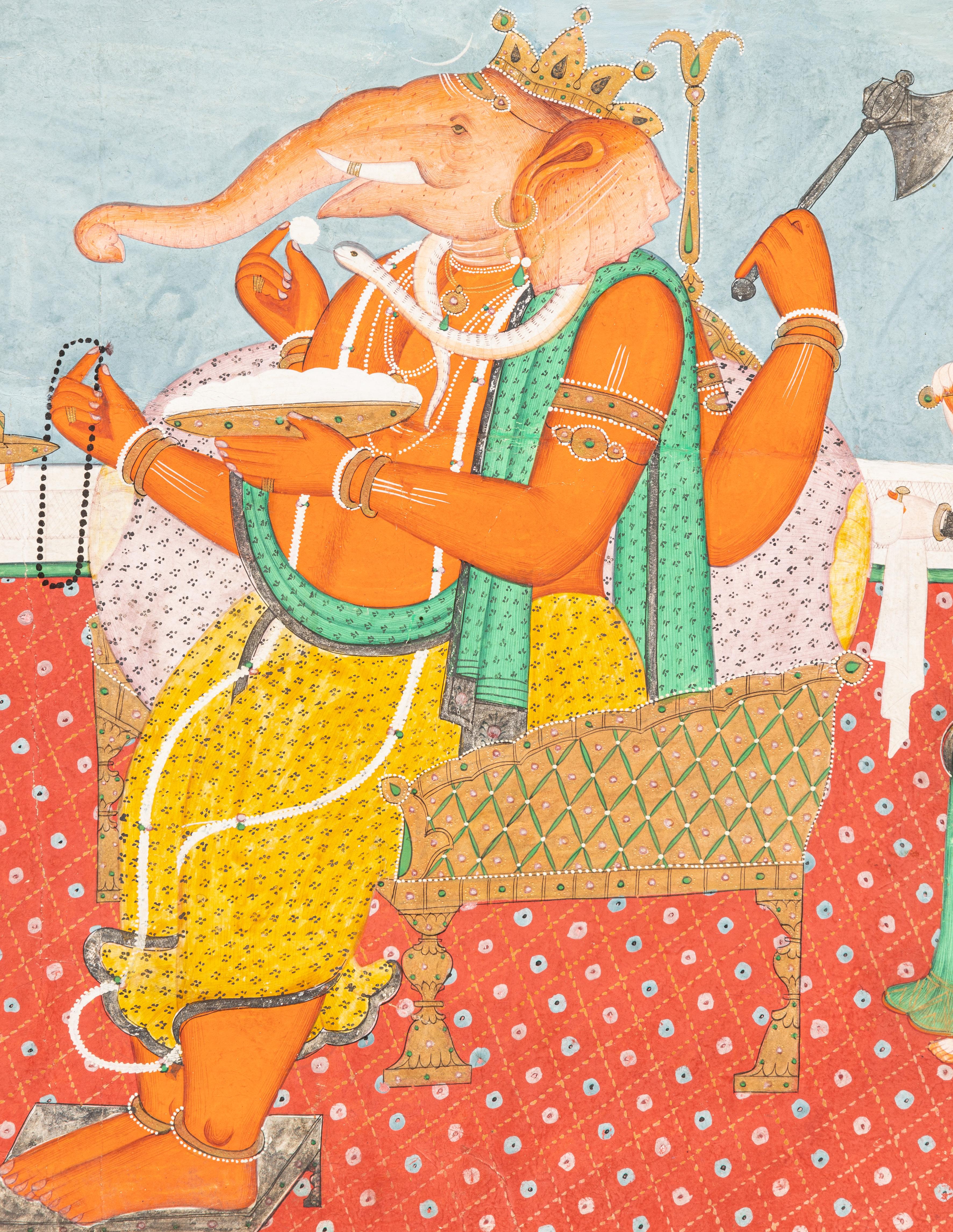

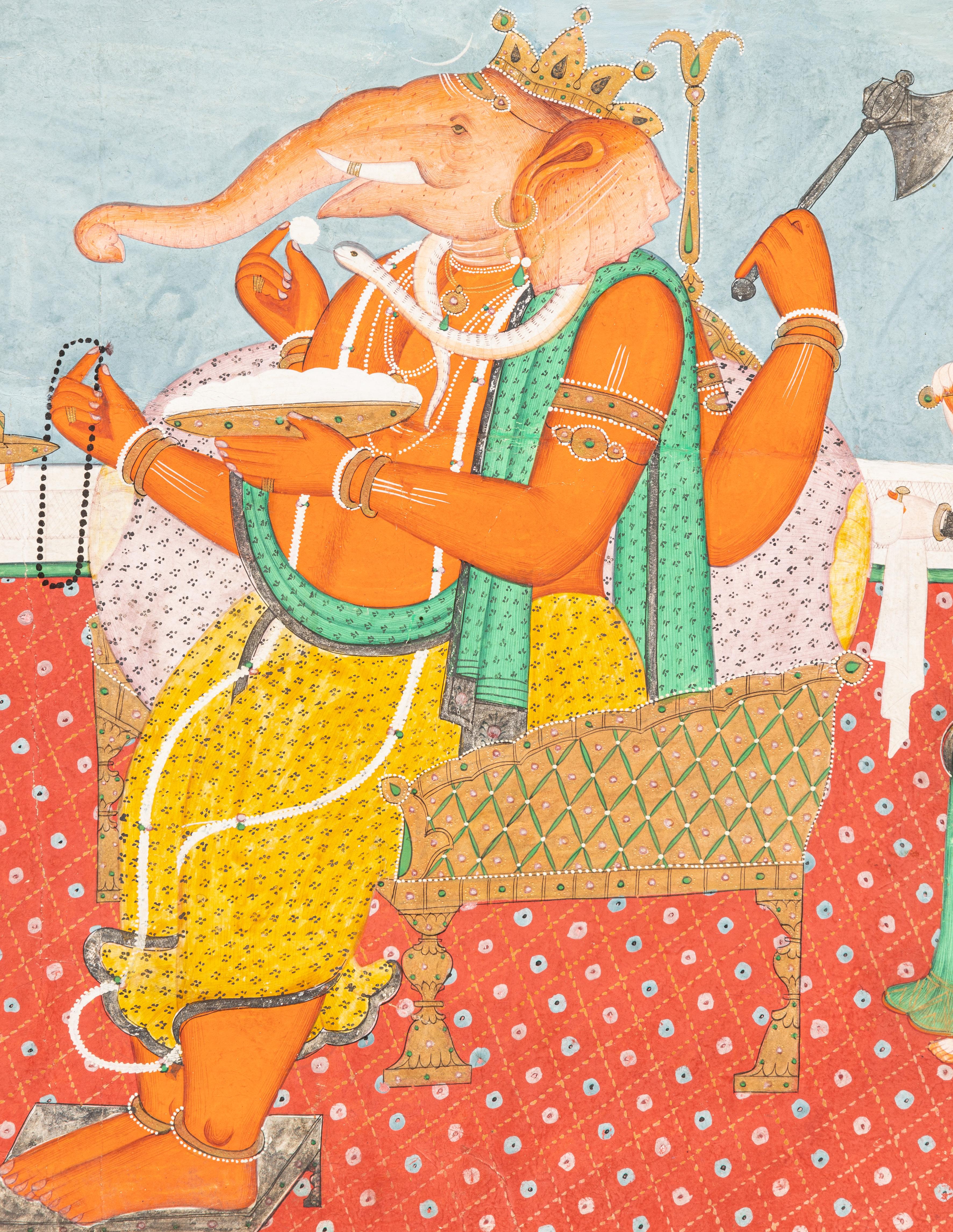

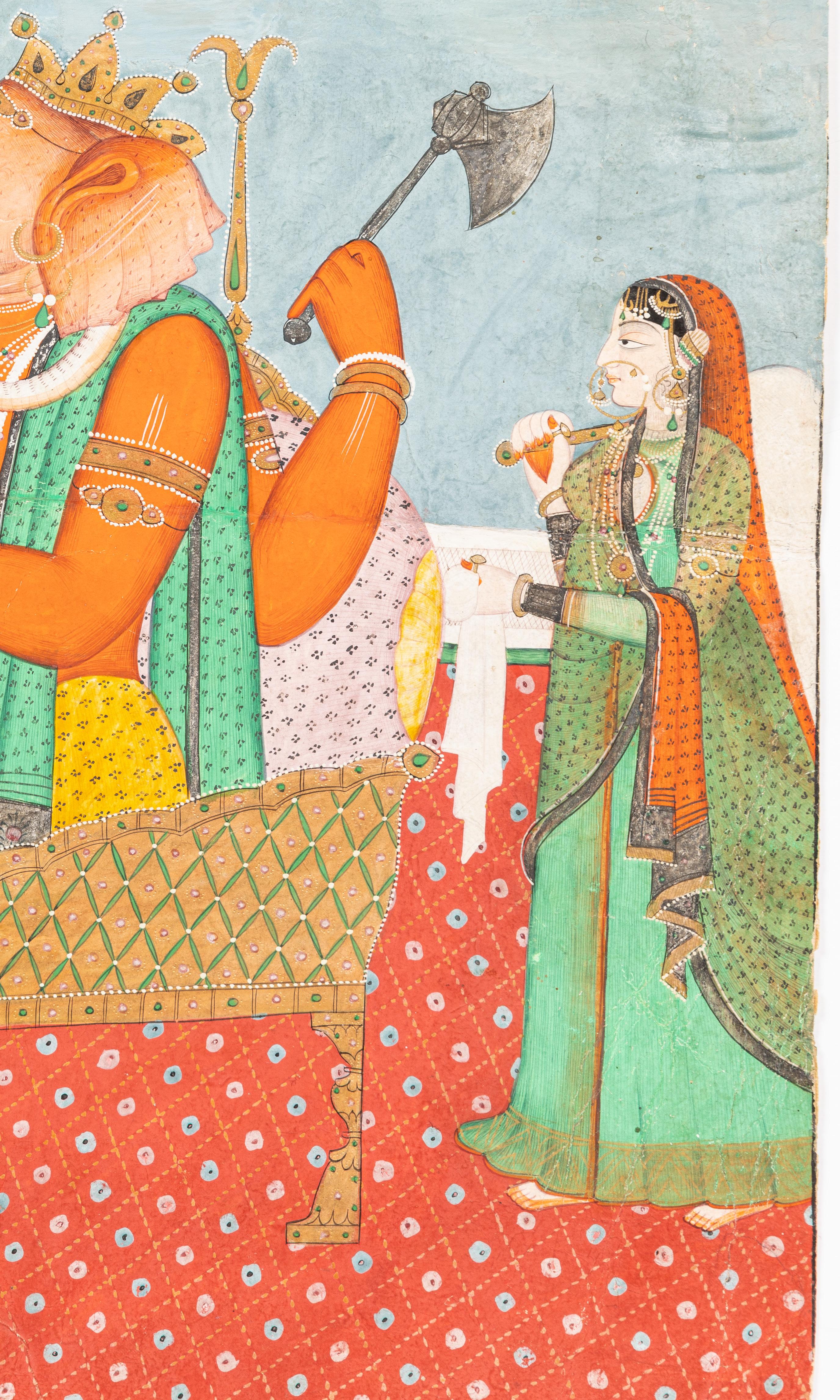

Ganesha Enthroned

Kangra, first half of the 19th century Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 10 3/4 x 11 in. (27.2 x 28 cm.)

The bestower of good fortune, remover of obstacles, and god of new beginnings sits here enthroned, consuming sweets. He appears at ease, his gaze as relaxed as his posture, encouraging his snake to take part in the snack. The tilaka and crescent moon which grace the divine elephant-headed god’s temple are marks of his divinity and transcendent knowledge. He is attended to by two lavishly dressed women in full jewelry sets and layered textiles in hues that create continuity in the palette and connect the attendants to their object of veneration. Playful patterns and bright colors give great vibrancy to this miniature painting of the widely adored god, Ganesha.

35

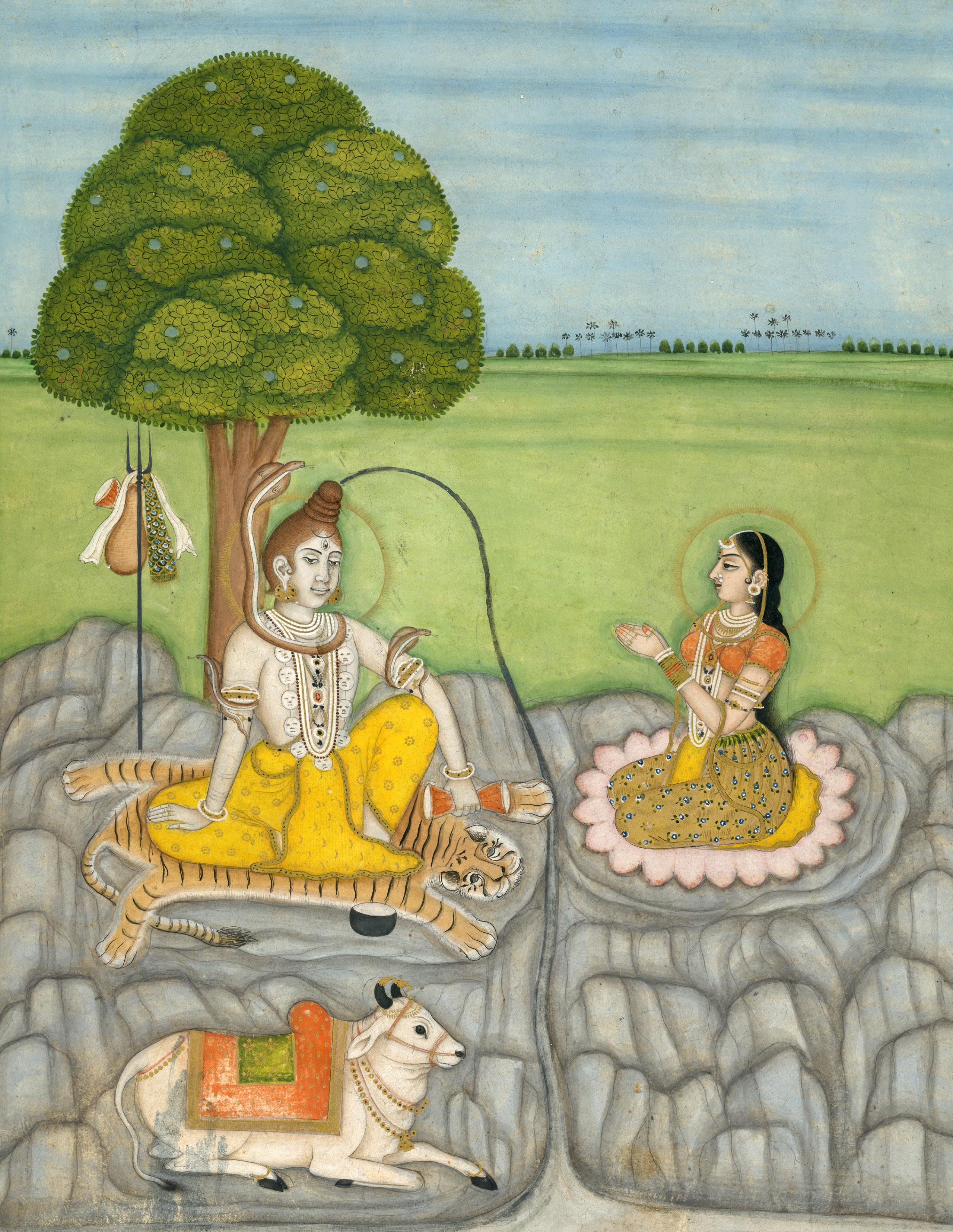

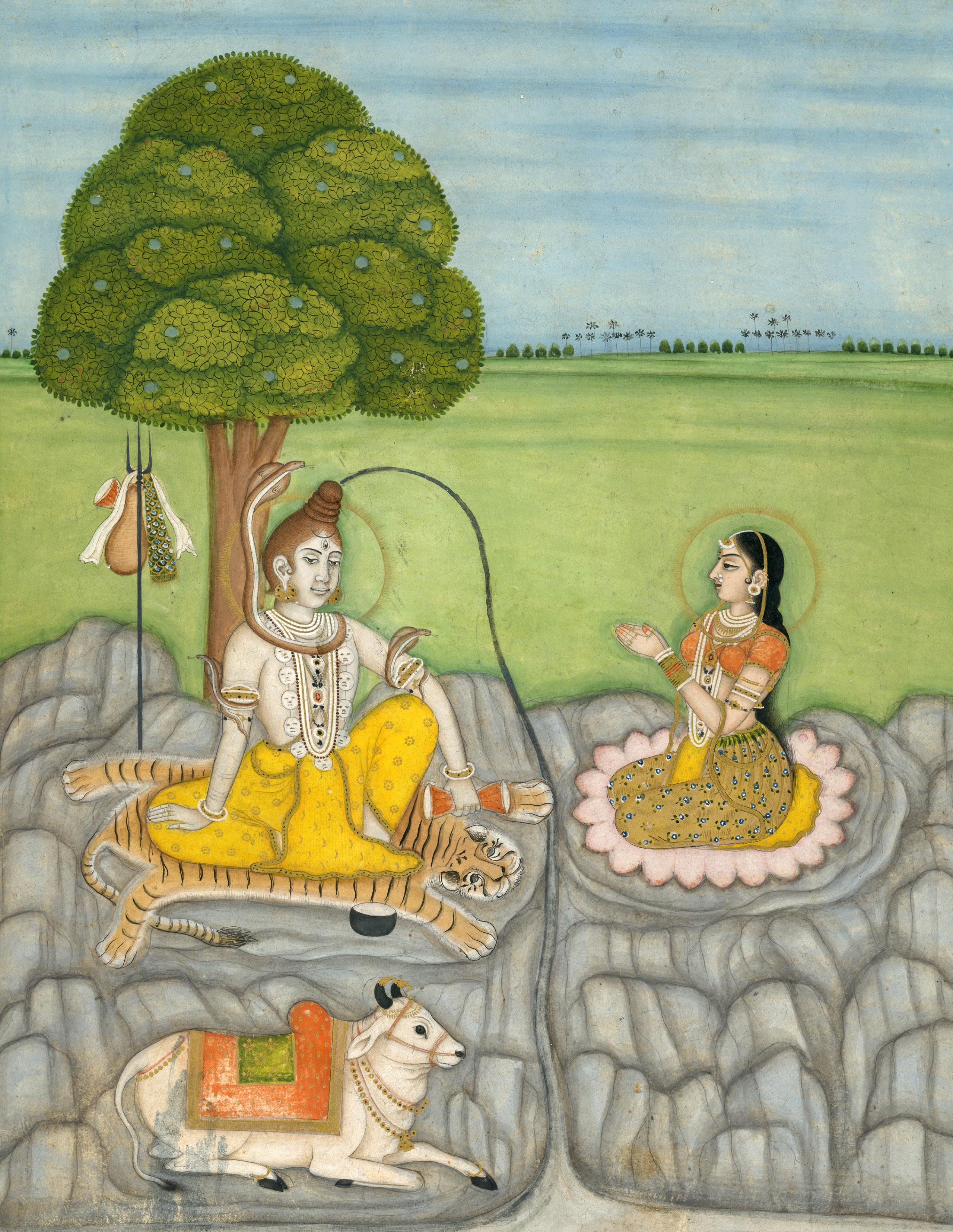

Shiva and Parvati

Murshidabad, circa 1780

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 10 x 8 in. (25.7 x 20.3 cm.)

Folio: 11 x 9 in. (28.2 x 22.9 cm.)

The present painting depicts Lord Shiva and Parvati seated under a tree atop Mount Kailash. An even line of trees and palms dot the horizon, dividing a clear blue sky and a vast expanse of green. Shiva, seated on a tiger pelt, is adorned with serpents which curl around his neck and arms. On his forehead is his third eye, topped by a crescent moon. From his piled hair flows the river of Ganges which splits the mountain in two. He is equipped with two damaru —a divine instrument which produces the sounds that create and regulate the universe—one in his proper left hand, and another hanging from his trident, along with pennants that billow in the breeze. Beside him is Parvati, seated upon a lotus flower. She holds her hands open in respect as she gazes upon her lover. Both she and Shiva have glowing nimbuses marking their divinity. Below the couple rests Shiva’s faithful vahana, Nandi, the sacred bull.

36

Folio from an Usha-Aniruddha Series:

Chitralekha Visits Aniruddha in Dwarka Garhwal, circa 1840

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper 9 x 12 in. (22.9 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Private European Collection.

The present painting comes from an Usha-Aniruddha romance series in which Usha, daughter of Vana, King of the Daityas, has a dream of a wonderfully handsome prince with whom she instantly falls in love. Usha, calling upon her friend, the magical Chitraleka, speaks thus, “Listen carefully my friend. My husband is very attractive, his eyes are beautiful like a lotus, his gait is gracious like that of an elephant. If you do not produce him before me I will die” (H. Dehejia, and V. Sharma, Pahari Paintings of an Ancient Romance: the Love Story of Usha-Aniruddha, New Delhi, 2011, p.28). Chitralekha aids her in drawing portraits of all the princes until Usha recognized Aniruddha among them–the grandson of Krishna!

Here we see Chitralekha in the holy city of Dwarka, built by the divine architect Vishwakarma. The majestic palace is made of pure gold, its columns and arches adorned with glittering jewels that sparkle like the stars in the sky. Chitralekha, leaning against a golden arch, gazes upon the sleeping figure of Aniruddha, his princely crown beside him. When Chitralekha awakens the prince, he explains that he too has had a dream of a beautiful romance. Thus, he agrees to accompany Chitaleka to Usha.

Sleeping in a chamber just to the left of Aniruddha is Krishna, who has a nearly identical countenance to his grandson–the only distinguishing feature being his crown, which unlike Aniruddha’s, bears his signature peacock feathers. The male figure beside him is likely a messenger, there to alert Krisha that Aniruddha has disappeared. When Krishna finds his grandson gone, he wages war on Usha’s kingdom, and a great battle ensues.

See a similar folio from a Kangra Usha-Aniruddha series, currently in the Victoria and Albert Museum (acc. IS.11-1968). In this folio, Chitaralekha reveals her portraits to Usha and then magically flies through the sky on her way to find Aniruddha. The Garwhal and Kangra traditions are both known for their exquisite romantic charm. The present folio, however, is executed in a palette that would surely steal the eye away from a comparable pastel-colored Kangra illustration of the same subject.

37

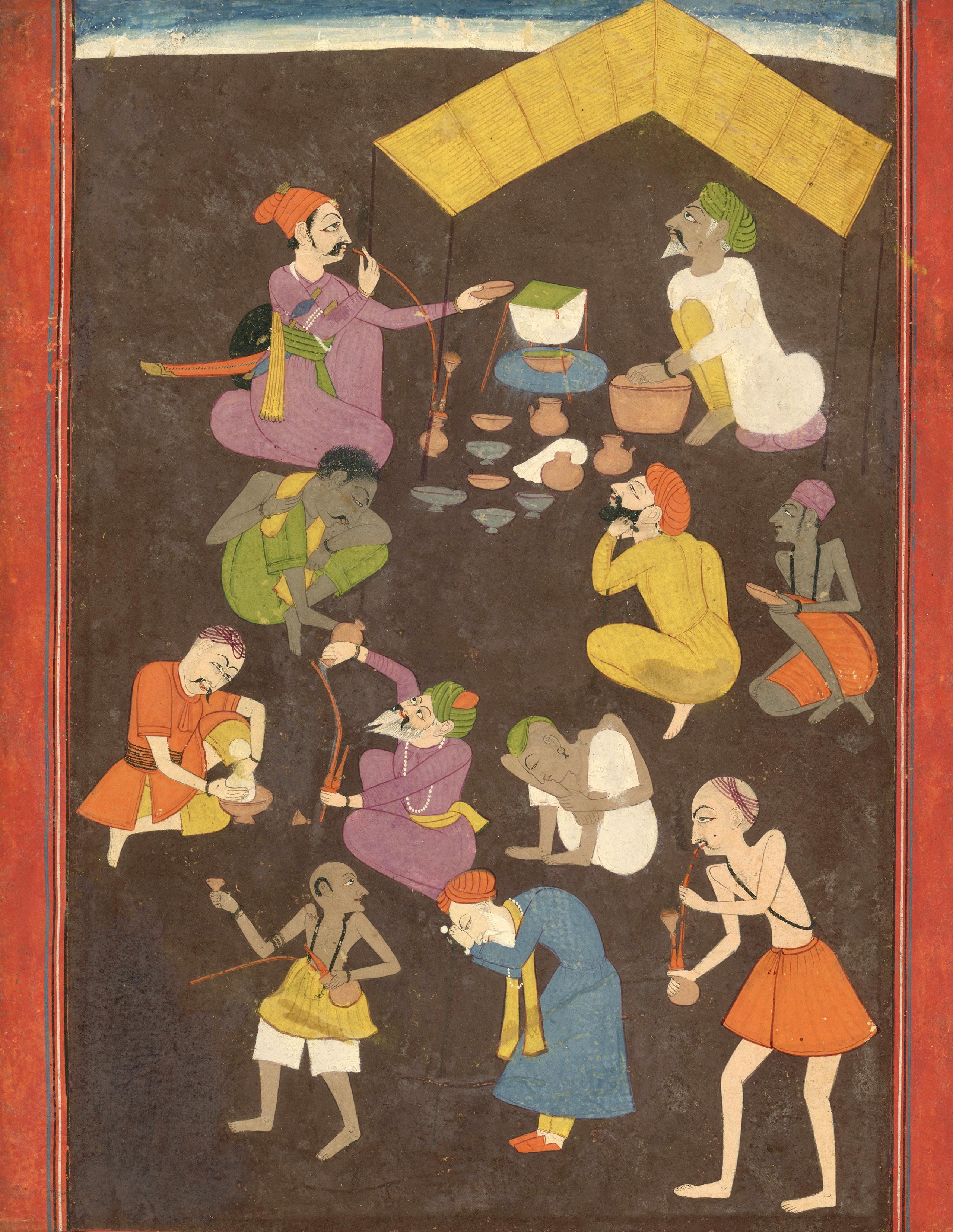

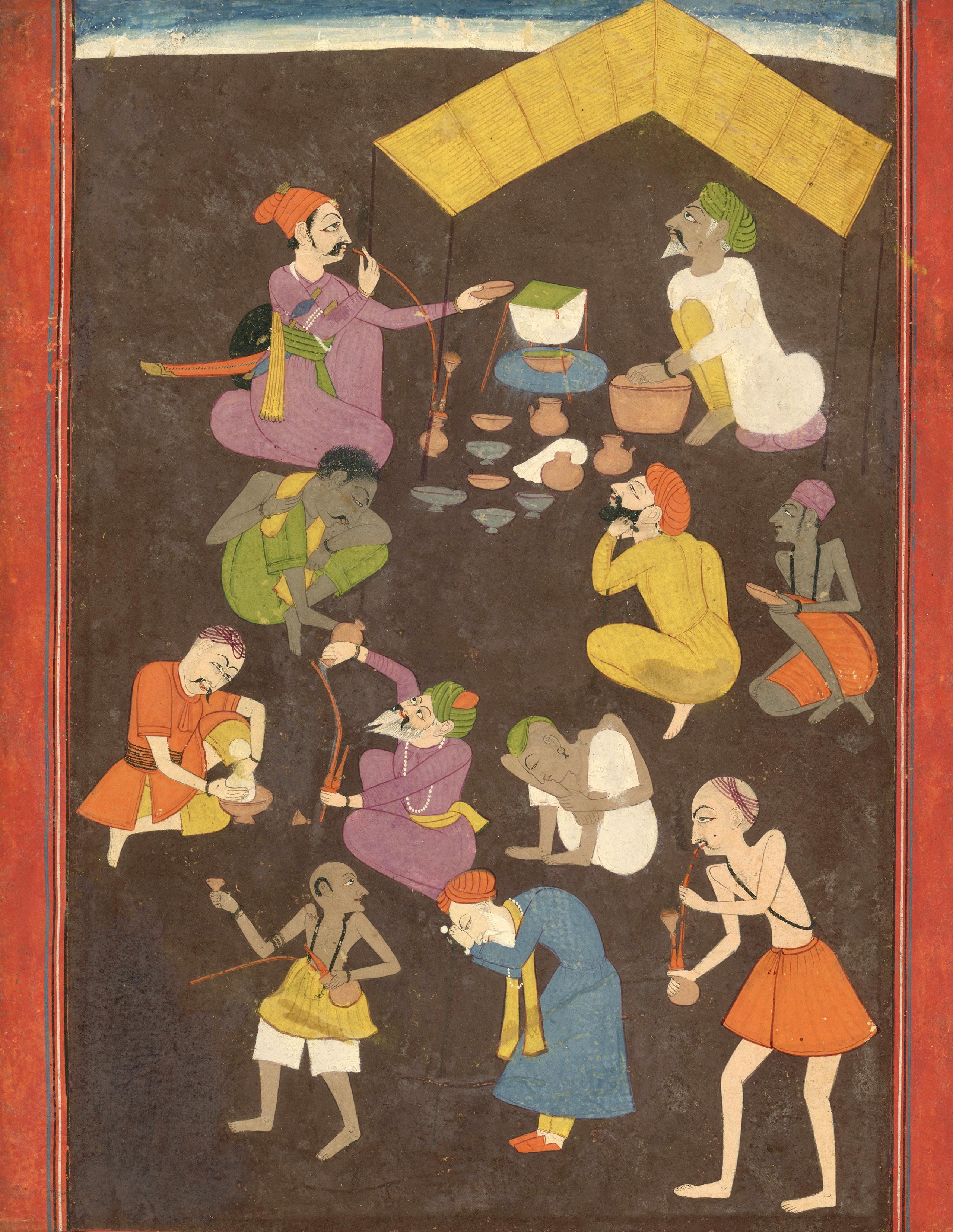

Inebriated Ascetics

Rajasthan, circa 1750-60

Opaque watercolor on paper

Image: 8 ⅝ x 5 3/4 in. (21.9 x 14.6 cm.)

Folio: 9 7/8 x 6 7/8 in. (25.1 x 17.5 cm.)

Caricatures of inebriated ascetics showing the effects of opium and bhang were a popular theme in Indian painting from the 17th through the 19th centuries. These substances were used by holy men to aid them in achieving a state of spiritual ecstasy, especially in the festivals and rituals associated with Shiva. Although such illustrations were also produced by Mughal and Pahari schools, the Rajput representations tend towards ridicule, a feature that can also be seen in Rajasthani caricatures of firangis (foreigners).

The present painting illustrates a chandu-khana, which roughly translates to ‘opium den.’ At the top of the scene two men beneath a tent are preparing bhang, a drink made with marijuana, with a couple of onlookers eager to fill their bowls. Below them a group of men revel in their intoxicated states, some crouching with their eyes closed, others smoking opium from their nargilas. A number of them are depicted shirtless, exaggerating their scrawny and bony appearances. The ascetics are arranged in rough rows against a plain brown background (almost as if a series of figure studies), a compositional model that appears in other paintings of this theme. The resulting lack of perspective informs the Rajput origins of the painting.

For another 18th-century depiction of this subject from Rajasthan, see the San Diego Museum of Art (acc. 1990.722). Note the similar style of composition as well as the individualized rendering of each figure.

38

Nobleman on a Terrace

Attributed to Pandit Seu and his family workshop

Guler, late 18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 ⅛ x 5 ⅜ in. (18.2 x 13.6 cm.)

Folio: 11 ½ x 7 7/8 in. (29.1 x 20.1 cm.)

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 20 March 2019, lot 713.

A nobleman in a vivid green jama with an elaborate floral and jeweled belt, necklaces of rubies, emeralds and pearls that match his embellished turban surmounted by a feathered sarpech, appears dignified atop a white marble terrace. He relaxes before an elaborate drawstring bolster atop lavish textiles as he holds the end of a hookah, before which a heated vessel sits emitting wisps of smoke. The elegant composition is worthy of close comparison to a figure in the same posture, garb and environment as the present nobleman, attributed to the master painter Nainsukh: a drawing of Mir Mannu in the Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh (acc. no. B-60), illustrated by B.N. Goswamy in Nainsukh of Guler, Zurich, 1997, pp. 102103, no. 27.

Since Akbar’s time, the Mughal Empire exerted suzerainty over the small principalities within the rich landscape of the Punjab Hills. The present painting is a result of that influence, as it was very likely painted from an imperial Mughal model. The painting is, nevertheless, of the highest quality and thus attributed to the famed atelier of Pandit Seu of Guler—an artist who credited with aiding in the shift to a more formal style with the transmission of Mughal techniques learned directly from disbanded artists from Aurungzeb’s former atelier.

39

A small bronze figure of Vajrasattva

Tibet, 14th century

3 1⁄2 in. (9 cm.) high.

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item no. 61643.

Provenance:

Cees van der Plog, 1995, by repute.

Bonhams Hong Kong, 2 Oct 2018, lot 132.

Vajrasattva or ‘The Vajra Being’ is a direct embodiment of the adamantine dharma of Tibetan Buddhism. He holds a vajra or dorje in his proper-right hand, symbolizing his mastery of Tantric Buddhist method, and a bell or drilbu in his left to indicate his primordial wisdom. Vajrasattva is the ultimate teacher and has immense purification power.

While this bronze sculpture of Vajrasattva is petite in size, it is aesthetically powerful: with a soft face, lifted chest, and lifelike hands and feet. By the twelfth century, Tibetan artists mastered bronze casting technology as sophisticated as that of the Pala Empire, and by the fourteenth, Pala artists were no longer active in Tibet (von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Vol. II: Tibet & China, Hong Kong. 1990, p. 1092).

This present sculpture demonstrates how the late-Pala style of northeastern India was absorbed into a centralTibetan style that defined the ‘Monastic period’. The simple three-petal diadem with flared ties at the ears securing the flat band at the back of the head is typical of this sculptural milieu.

40

A buff sandstone torso of Vishnu

Central India, 12th century Sandstone

40 in. (101.6 cm.) high.

Provenance:

R.W. Leybourne Callaghan, alias Callaghan of India, Managing Director for Roche India and Honorary Consul for Ireland in Bombay, by 1984. Christie’s New York, 20 September 2006, lot 61.

This stele torso figure of Vishnu is adorning a Kirit Mukut (crown) . The upper left arm with the Chakra (discus) and the upper right arm with a foliate gada (mace) is reminiscent of the four-armed iconography of Vishnu. The iconographic attributes of discus and mace resonate to the role of Vishnu being the preserver of cosmic order in Hindu mythology; thus complementing the role of Brahma being the creator (responsible for the creation of the universe) and Shiva the destroyer (the reason for evolution).

Three deities at the top are flanked by the apasara (celestial beings) at both ends. The open-work in the center with the foliate patterns bedecks the nimbus of the deity. It is said that Vishnu descended on earth in the form of ten avatars (incarnations) to restore cosmic order. Four of these avatars of Vishnu can be seen on either side of the stele figure. It is suggestive that the sculpture would have once consisted of other avatars depicted on the two sides similarly.

The subject matter of the given piece is very similar to one of the steles at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York which is attributed to Punjab in Northern India.

41

A gray schist figure of a seated Bodhisattva

Gandhara, 2nd/3rd century

Blue gray schist

25 in. (63.5 cm.) high.

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item number 1322

Provenance:

Sotheby’s New York, 20 March 1997, lot 47.

Sotheby’s New York 20 March 2013, lot 267.

The Buddha is seated in dhyanasana with a serene face and the marks of nobility encircled in a halo, with his hands clutching his necklace. The robe drapes over one shoulder, undulating in high relief across the torso, gathering in a fold over the legs and falling over a cushioned seat.

This image of the Buddha clad in robes of draping folds and seated with his hands gently resting in his lap epitomizes the classical style of sculpture coming from the ancient region of Gandhara. Spanning from the 1st through the 5th centuries C.E., the ancient region of Gandharan comprised the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent and held a vital political and cultural position along the Silk Routes.

The long and dynamic history of the region included epic conquerors, including Darius (550-486 B.C.E.), Alexander the Great (356- 323 B.C.E.) and Menander (342/41 -290 B.C.E.), all of who expanded the Hellenic worldview across the territory. In 60 C.E., when the Kushans conquered the region, their political and economic prowess combined with the refined philosophies of the local Indic Buddhist religion marked an apex of political, religious and cultural syncretism for nearly four centuries largely influencing distant regions in both Central Asia and China.

The Greco-Roman style, characterized by a symmetry of form, blended seamlessly with the spiritual philosophies of the Mahayana Buddhists. The ideals of human beauty and proportion within the Classical world were easily assimilated to the religious aims of the Mahayana Buddhists, whose ultimate nirvana lay in their practices of selfless service to humanity. At the heart of these teachings was the example of the Buddha, who achieved enlightenment and dedicated his life thereafter to teaching others the path to attain nirvana.

The seated Buddha is the most iconic image of the Gandharan artistic canon, integrating the proportions of the Classical style with the internal meditative equilibrium achieved by Shakyamuni Buddha. The waves of hair rising into a prominent top-knot, the almond-shaped eyes and rounded face framed in a halo, the fall of the drapery over the body and legs, the restful posture of meditation, all seen in this fine example, are hallmarks of Gandharan style.

42

Thangka depicting Saddha Milarepa

Tibet, 18th/19th century

Mineral pigments

Framed: 27 ⅛ x 39 ½ in.(69 x 100.5 cm.)

Published:

Himalayan Art Resources, item number 1318.

Provenance:

Property from the José M. Neistein Collection.

Religious Art in Tibet is usually classified into three major broad categories: murals in temples and monasteries, manuscripts and cloth paintings –Thangkas. A Lama (most likely Milarepa) seated in a contemplative posture is revered and offerings are made to him by attendants, kings and saintly beings. Buddhist Arhats (elders) and Lamas (teachers) are typically dressed in monastic robes, emphasizing their renunciation of worldly attachments and commitment to the Buddhist path.

The muted red nimbus surrounding Milarepa symbolizes his spiritual enlightenment.The kingly figure at his feet makes offerings to him. The three wrathful deities at the right hand side are the representations of wrathful deities who serve as protectors and destroyers of ignorance. Wrathful deities are important iconographic features of the Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. The sense of scale in rendering the figures depicts the hierarchical and monastic order. Saddha practitioners portray Saddha (faith and conviction) in the triple gem – the enlightened (the Enlightened One), the Dharma (his teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). The Thangka here is very likely an embodiment of the same essence.

The Thangka as a thorough representation of religious stratum outlines the multifold pathways leading to salvation and enlightenment. The Lamas and Arhats, the wrathful deities and other sentient beings showcase a monastic order of the religion.

As pointed out by Dr. Pal in Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries religious modes of artistic expression like the Thangkas conform to veracity and consistency and therefore stylistic changes and adventurism do not transpire as easily; which is why Thangkas remain definitive bearers of Buddhist doctrine and philosophy.

43

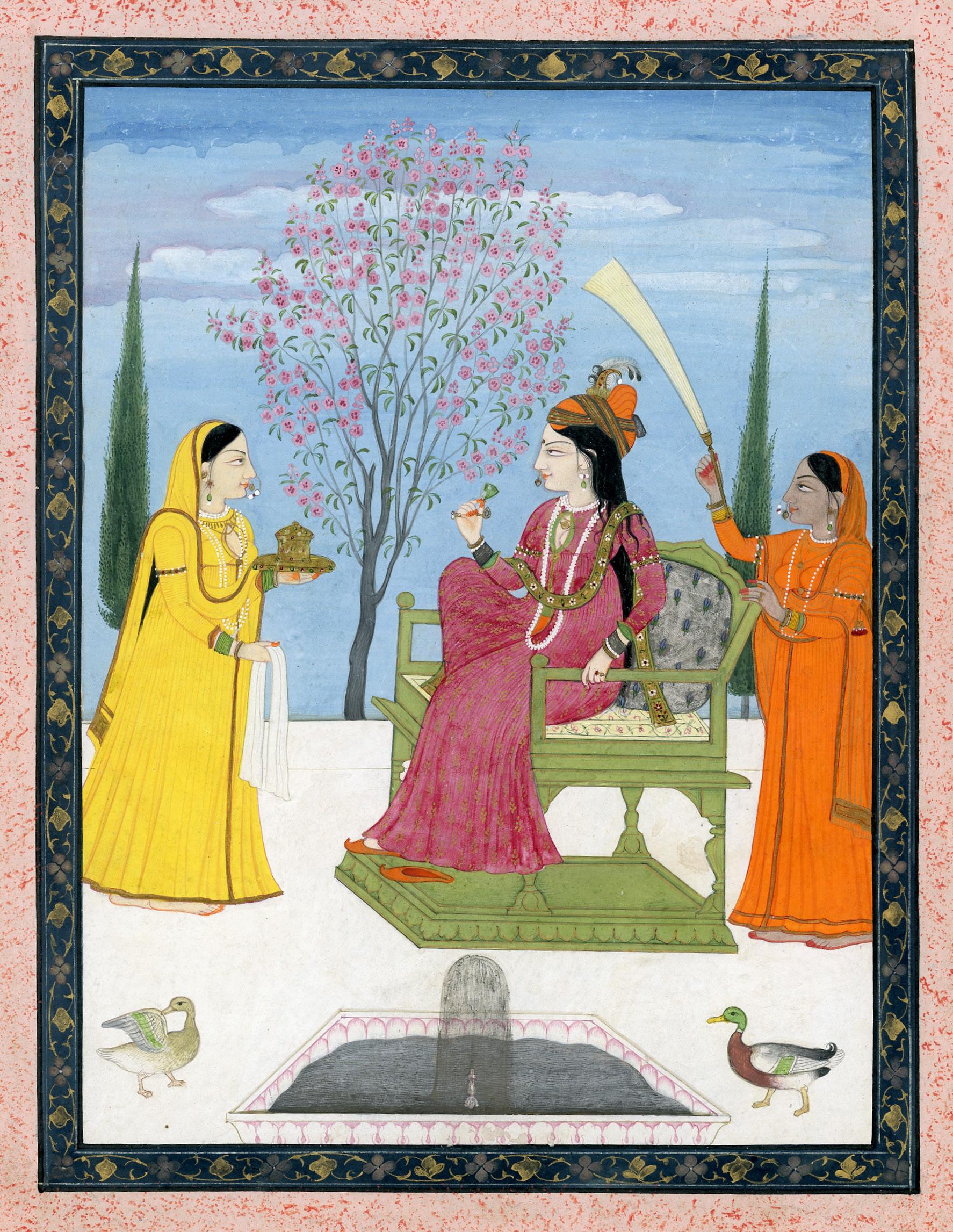

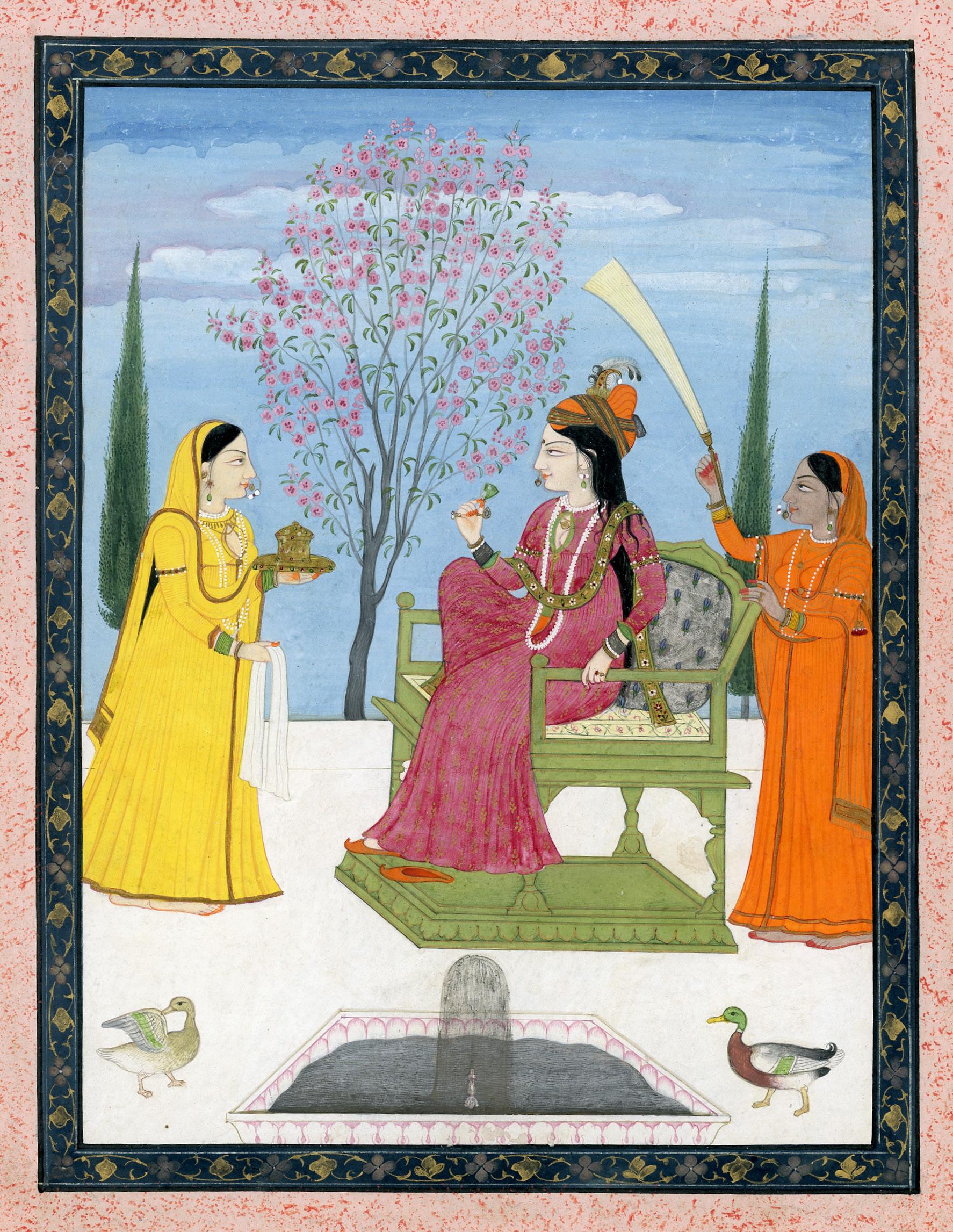

Maharaja Abhai Singh Receiving Thakur Bhandari Girdhar Das

Jodhpur, circa 1725-1735

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

12 ¼ x 9 3/4 in. (31.1 x 24.8 cm.)

Published:

Rosemary Crill, Marwar Painting: A History of the Jodhpur Style, Mumbai, 2000, p. 75, fig. 46.

Provenance:

The collection of Robert O. Muller.

Christie’s New York, 14 September 2010, lot 203.

Maharaja Abhai Singh (b. 1702), who ruled Jodhpur from 1724 to 1749, sits here larger than life on a silver throne, holding a small ceremonial whisk and an upright sheathed sword. Two courtiers stand behind him, one waving a morchal (a peacock-feathered whisk) as a symbol of his royal authority. He is receiving his thakur (vassal) Bhandari Girghar Das, a Rathore nobleman from a Marwari thikana or fiefdom who kneels respectfully at his feet.

Abhai Singh sits looking blatantly up past the petitioning vassal. He is dressed in a long, brilliant orange pleated jama with a gold floral designed patka and strands of pearls and precious gems which weigh down his shoulders. His head is topped with a silk Rathore-style pagri that sports ornate jewels and pearls, surmounted by a fine sarpech, his bare feet resting on a small plinth.

The group is depicted like a frieze or still-life against the marble wall of a white pavilion with two swimming ducks and a fountain positioned below. He is depicted here in his full majesty and authority–still a relatively young man, probably in his late twenties.

The rule of Abhai Singh marked an important period of development in court painting resulting in some of the finest paintings in Marwar.

44

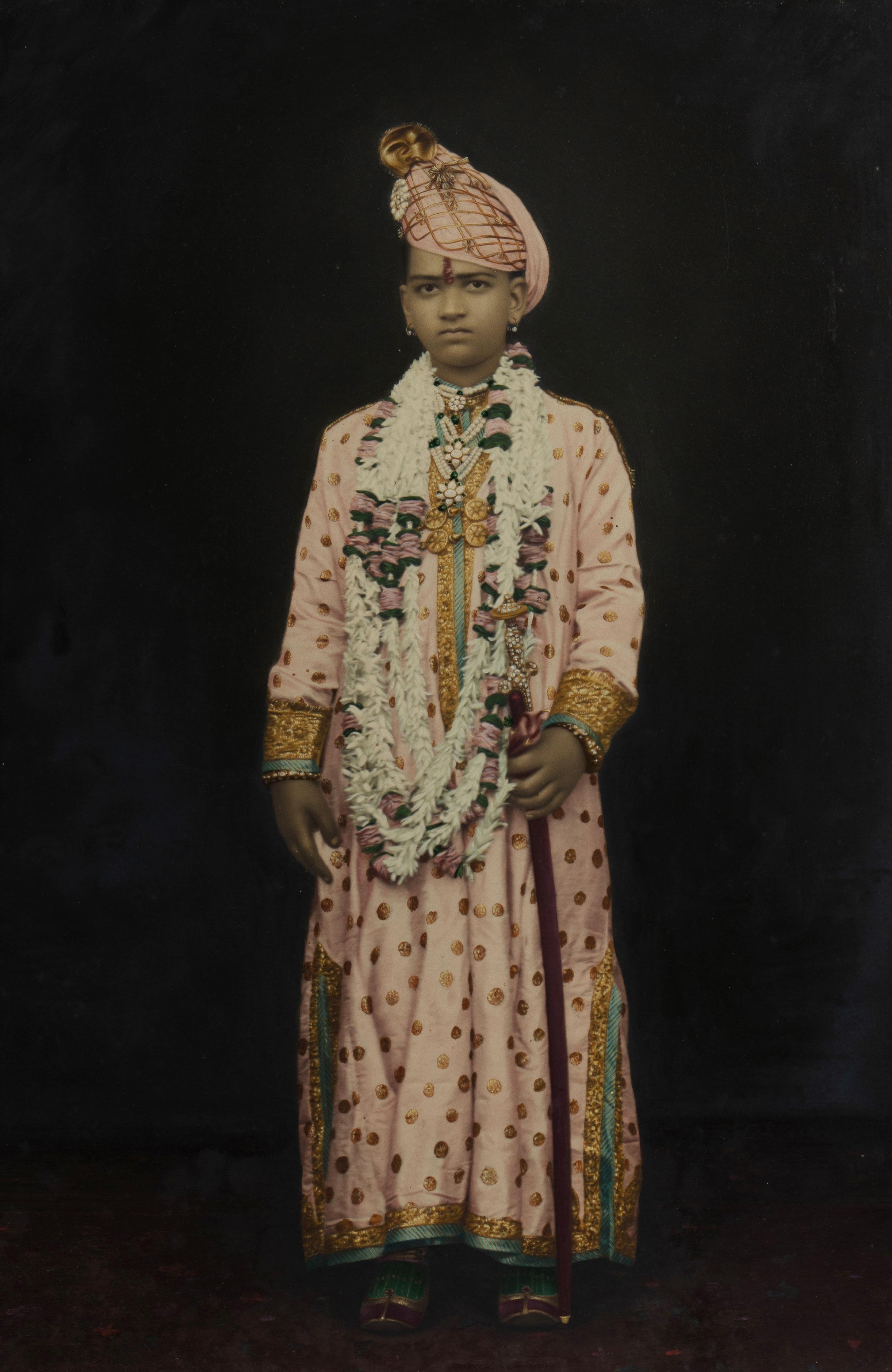

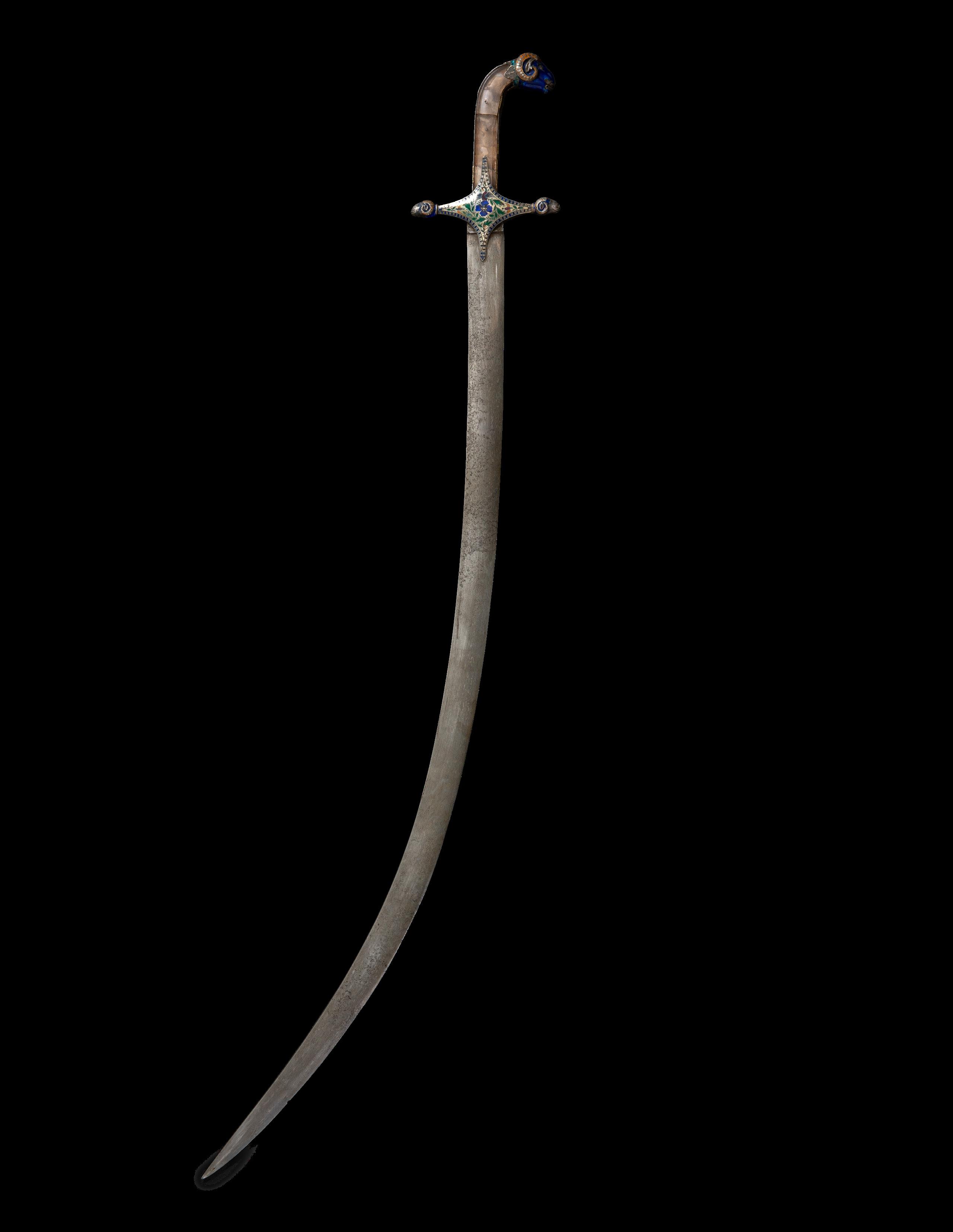

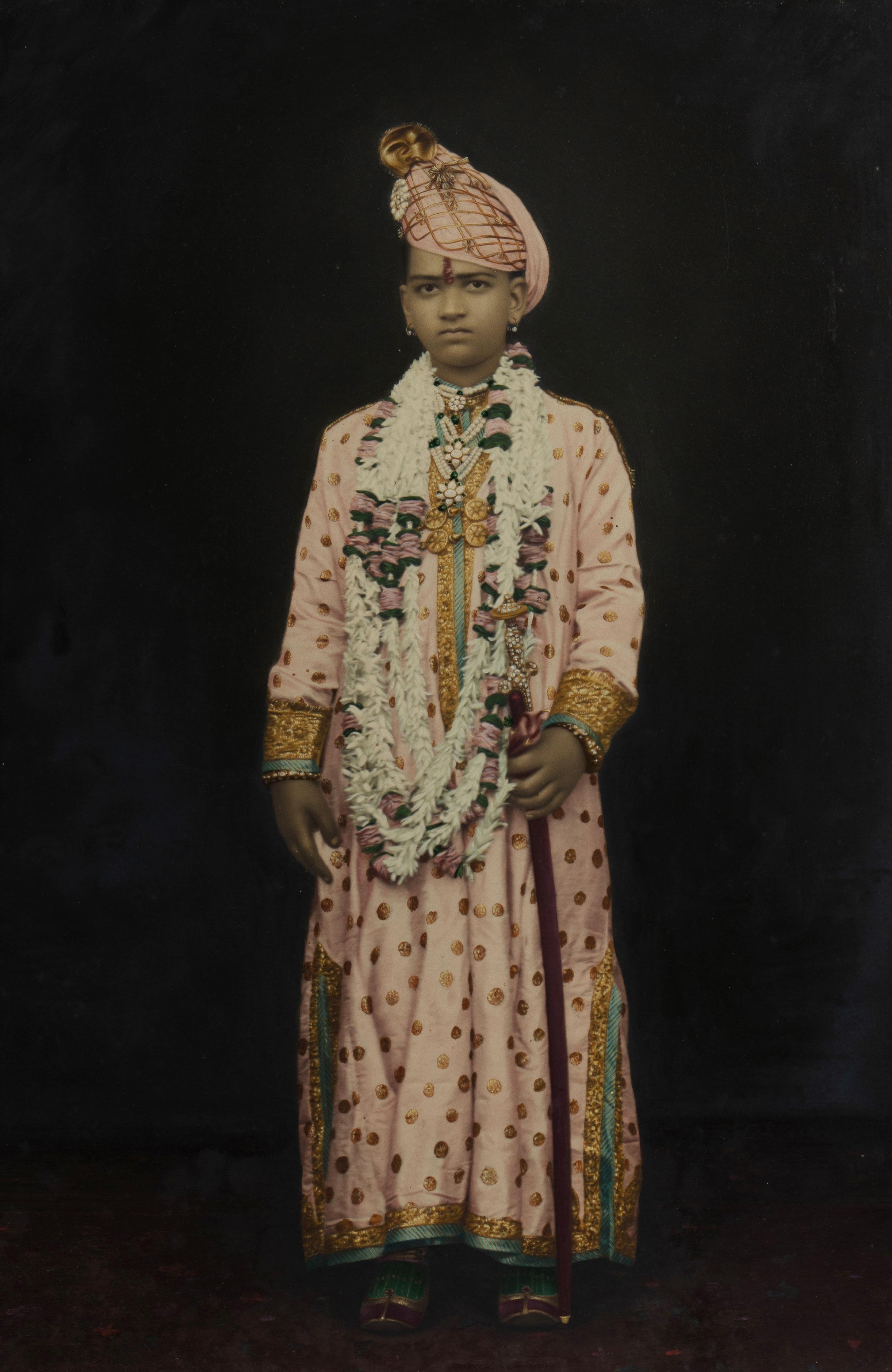

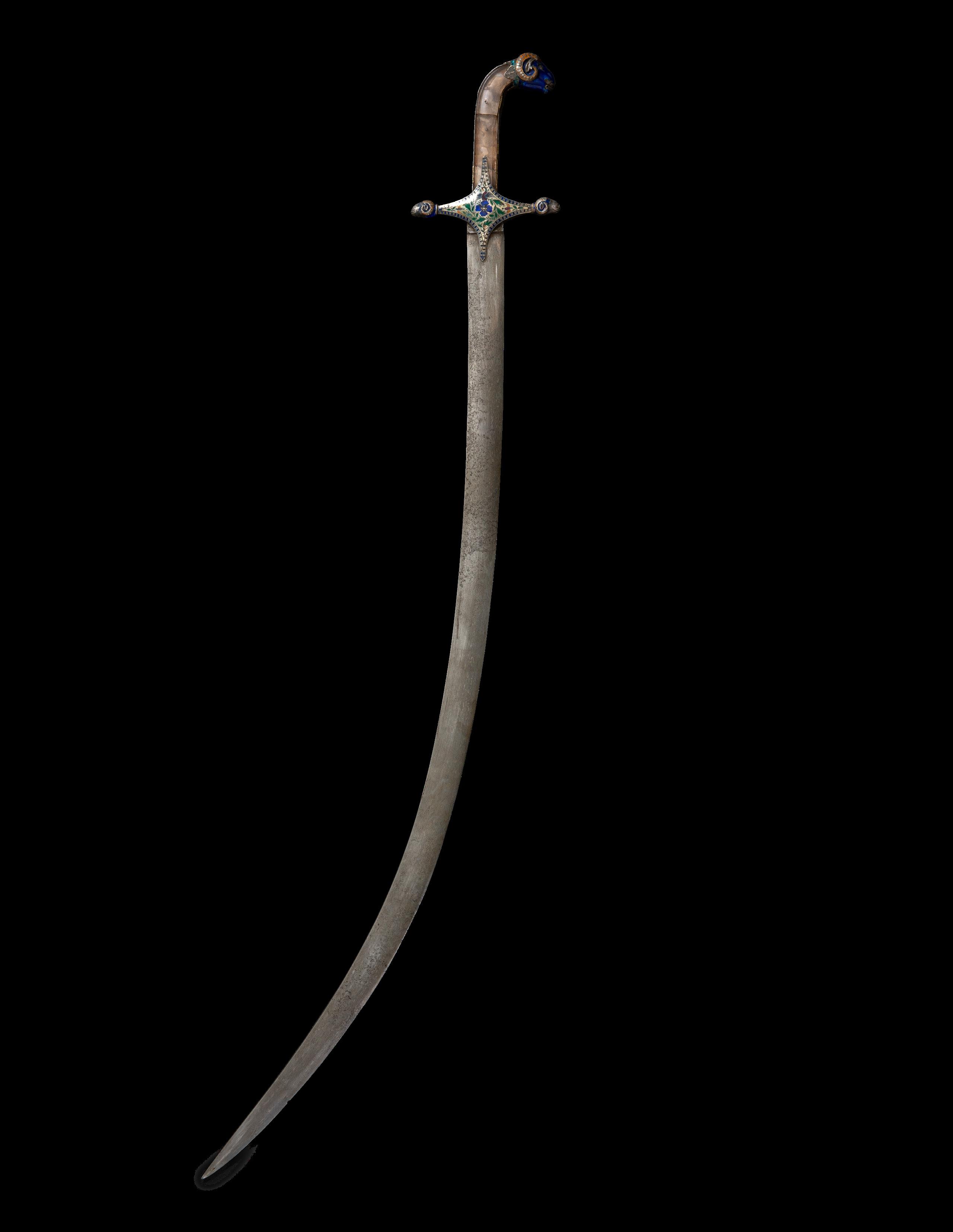

Shah Jahan at a Jharokha Window