13 minute read

13 Trotting Horse

RELIEF WITH THE LAMENTATION

BALTHASAR PERMOSER Kammer near Otting, Chiemgau, 1651–1732, Dresden

Advertisement

Rome, circa 1680

Ivory Height: 17.4 cm, width: 11 cm, depth: 2.5 cm

Provenance: According to family tradition owned by Pedro de Sousa Holstein, 1st Duke of Palmela (1781–1850); Through inheritance Manuel de Souza e Holstein-Beck (1932–2011), 4th Duke of Póvoa; By descent until 2020.

Related Literature: Burk, Jens Ludwig. ‘Anmerkungen zu einigen Braunschweiger und Dresdner Werken des Kursächsischen Hofbildhauers Balthasar Permoser (1651–1732)’, in: Herzog Anton Ulrich zu Gast in Dresden, exh. cat., Dresden Residenzschloss, Dresden 2012, pp. 33–53.

Schmidt, Eike D. ‘Ein dokumentierter Kalvarienberg aus Elfenbein von Balthasar Permoser in Florenz’, in: Pantheon, 55 (1997), pp. 91–112.

Siegfried Asche, Balthasar Permoser. Leben und Werk, Berlin 1978.

Theuerkauff, Christian. ‘Zu Francis van Bossuit (1635–1692), beeldsnyder in yvoor’, in: Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, 37, Cologne 1975, pp. 119–82. The carved relief, partly modelled in the round, depicts the mourning of the death of Christ – the so-called ‘Lamentation’, after the body of Christ is taken down from the Cross and before it is laid in the tomb. Although not explicitly mentioned in the Bible, the Lamentation, as part of the burial ritual, fits well into the story of the Passion and has been represented in the visual arts since the Middle Ages. As the subject does not form part of the established canon, the figures comprising the group of mourners vary. In addition to the Virgin Mary and John, the Beloved Disciple, other women who witnessed the Crucifixion are sometimes also depicted (Mark 15:47; Luke 23:55). Occasionally the group of mourners is expanded to include Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathia who took Christ down from the Cross and later laid him in the tomb. The place is not defined. The group of mourners is variously shown directly beneath the Cross, next to an empty sarcophagus or in the burial chamber.

Mary, John and Mary Magdalene, mourning the death of Christ, are shown in this small relief. Mary, overcome by grief, gazes heavenwards, her arms folded across her chest. A sword, thrust into her breast, symbolises the pain she is suffering. Such a depiction is known as a ‘Mater dolorosa’ – Our Lady of Sorrows – and is based on the prophecy of Simeon: “ … a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also” (Luke 2:35).

The emotional pain of the mourners, effectively expressed through posture and gesture, is given special emphasis. Bold sweeping lines tie the figures in closely to one another and lend expression to the drama of the moment. The ladder used for the descent from the Cross on Calvary can be seen top left in the delicate bas-relief. There is also the suggestion of a sarcophagus. Grieving putti and the small faces of seraphim people the sky.

26

Fig. 1. Balthasar Permoser, The Entombment, 23 x 14 cm, circa 1677/1680, ivory, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, inv. no. 30/1949

Figures carved almost in the round that step out of the virtual plane of the relief and draw closer to the viewer are juxtaposed with the graphically delicate, partly translucent and wafer-thin working of the ivory. This is evidence of a virtuosity exhibited by only a few ivory carvers in the 17th century.

Stylistically, the relief can clearly be classified to the œuvre of Balthasar Permoser. The relief of the ‘Entombment’ in the Victoria & Albert Museum (fig. 1), firmly ascribed to Balthasar Permoser, is very similar to the ‘Lamentation’. Mary Magdalene is shown here in a modified way sitting on the ground; the Virgin Mary is being supported by two women while John is about to place the corpse in the sarcophagus. The treatment of the folds in the garments and the working of the hair are comparable. The mourning putti and seraphim in the heavens ressemble the chorus of putti in the ‘Lamentation’. The execution of the landscape in the background and that of individual motifs such as the plants on the ground and Mary Magdalene’s ointment vessel are even identical.

Permoser created the London relief around 1677–80 in Rome where he went in 1676 after his apprenticeship in Salzburg and Vienna. He studied the ivory carvings there with great intensity and, presumably, had contact with the well-known and highly skilled Flemish ivory sculptor Francis van Bossuit (1635–92) who was also in Rome at that time. Permoser must have known Bossuit’s relief of the ‘Entombment’ (circa 1675)1 as he adopted certain motifs, such as the putto at the very front of the relief supporting Christ’s limp body.

Permoser’s work attracted the attention of the Electoral Prince Frederick Augustus, later Elector of Saxony and King Augustus II of Poland, when on his grand tour to Italy in 1687–91. In 1689 the Elector called Permoser to Dresden as sculptor to the court.

Through his decorative sculptural work for the Zwinger, carried out from 1690 onwards during the reign of King Augustus the Strong, Permoser was to leave his mark on the city of Dresden like no other.

While in Dresden Permoser also continued to work in ivory as evidenced by his famous small ivory figures created together with the Dresden court goldsmith Johann Melchior Dinglinger (1664–1731).

26

1 Francis van Bossuit, Entombment of Christ, c. 1675, ivory, 25.8 x 15.5 x 3.4 cm,

The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario, inv. no. AGOID.29181, link: https://ago.ca/collection/object/agoid.29174

27

RELIEF WITH THE RAPE OF EUROPA

DOMINIKUS STAINHART Weilheim, 1655–1712, Munich

Late 17th century

Ivory Height: 10.8 cm, width: 20 cm

Monogram in the lower, left-hand corner: ‘DS’

Related Literature: Kessler, Hans-Ulrich. ‘Die Elfenbeinreliefs aus der Werkstatt der Gebrüder Stainhart’, in: Elfenbein, Alabaster und Porzellan aus der Sammlung des fürstbischöflichen Ministers Ferdinand von Plettenberg und der Freiherren von Ketteler, Stadtmuseum Münster, Patrimonia 193, Kulturstiftung der Länder, 2001, pp. 48–73.

Theuerkauff, Christian. ‘Kunststücke von Helfenbein. Zum Werk der Gebrüder Stainhart’, in: Alte und Moderne Kunst, Vienna, 16 (1972), 124/5, part 1, pp. 22–29, part II, pp. 30–33.

Feuchtmayr, Karl. ‘Dominicus Stainhart’, in: Thieme, Ulrich/Becker, Felix (eds), Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, vol. 31, Leipzig 1937, pp. 450–451. Europa was a Phoenician princess with whom Zeus fell in love. While playing with her companions on the beach of Sidon the god changed his appearance into that of a white bull and approached the maiden, lay down and let himself be stroked. After Europa had climbed, quite unsuspectingly, onto the bull’s back he ran off with her into the water and swam away. He reached the island of Crete where he revealed his true identity. She bore him three sons: Sarpedon, Minos, the later king of Crete, and Rhadamanthus, the judge of the dead.

Stainhart chose the dramatic moment of the abduction: Zeus, in the form of the mighty bull, carries the beautiful young princess over the stormy seas. Stainhart shows Europa’s distraught, gesticulating companions at the front of the composition in an extremely convincing manner.

The relief is characterised by the composition of its pictorial narrative. The dynamic, animated figures in the foreground are virtually completely undercut and almost freestanding. By contrast, the execution of the middle ground, with the depiction of Europa and the bull, as well as the background, is almost flat. These compositional features are typical of the ivory carver Dominikus Stainhart who signed the relief, below right, with his monogram ‘DS’. The faces with straight noses, the hairstyles with plaits and ribbons, the draping of the garments and the furrows in the surface of the tree and water all point to the style of this sculptor from Upper Bavaria.

Dominikus Stainhart came from a family of carvers from Weilheim. From 1674 until 1682 he travelled around Italy with his brother, Franz (1651–1695). Evidence exists that he was in Rome from 1678 until 1680 where he worked for the princely families of Radziwill and Colonna.

27

Fig. 1. Dominikus Stainhart, attributed to, The Rape of the Sabine Women, ivory relief, circa 1700, height: 11.5 cm, width: 16.8 cm, Collection in the Monastery Saint Florian, Linz, inv. no. Pl65.

A display cabinet that Dominikus decorated with ivory reliefs can still be seen in the Palazzo Colonna. It comprises a large, arched relief with a sculpted depiction of Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ and twenty-seven, small-format reliefs showing scenes from the Old and the New Testament. The overall composition for the display cabinet was designed by the architect Carlo Fontana who presumably specified the reliefs to be selected.1

In 1682 both brothers returned home to Weilheim and in 1690 Dominikus moved to Munich where he is mentioned by name as being on the committee of the Guild of Sculptors in Munich in 1705.2 This not only suggests that he was a member but also testifies to his standing as a sculptor. In early 1683 Dominikus sought a position at the Bavarian Court in Munich but without success. Nevertheless he sold a series of six reliefs depicting tales from the Book of Moses to the Elector of Bavaria, Max Emanuel.3 Around 1792 he delivered two pieces of ivory4 to the ducal ‘Kunstkammer’ in Munich and after his death his wife received payment for further four reliefs. The Bayerisches Nationalmuseum houses other works by Stainhart including one relief signed ‘D. Stainhart’ and three reliefs monogrammed ‘DS’: Diana and her Nymphs Surprised by Satyrs, Venus and the Dead Adonis, Apollo Slaying Coronis, and Apollo and Daphne – all originally from the ‘Stroganoff Collection, Leningrad’.5

Apart from these reliefs in Munich and the one presented here, no other works are known which are signed or have a monogram. The attribution of the majority of works to Stainhart is based on stylistic criteria. The four reliefs from the Stroganoff Collection and the Rape of the Sabine Women in the Monastery Saint Florian in Linz (fig. 1) are stylistically the closest ones to our relief.

Further works by Dominikus Stainhart can be found in numerous collections such as that in the Residenz in Munich, in the Liebieghaus Frankfurt, in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, the Wallace Collection, London, in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna and in Klosterneuburg.

27

1 Theuerkauff, op.cit., pp. 22f. and ill. 3 2 Feuchtmayr, op. cit., p. 450 3 These are now in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich 4 ‘2 helffenpainene stuck’, Feuchtmayr, op. cit., p. 450 5 Acquired in 1931 by the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich; Diana and her

Nymphs Surprised by Satyrs, monogrammed ‘DS’, c. 1690–1700, inv. no. 31/273; Venus and the Dead Adonis, monogrammed ‘DS’, inv. no. 31/272; Apollo Slaying Coronis, monogrammed ‘DS‘, inv. no. 31/271; Apollo and Daphne signed ‘D.Stainhart’ 31/270

28

FREDERIK V, KING OF DENMARK JOHANN CHRISTOPH LUDWIG LÜCKE Dresden, 1705–1780, Danzig

Copenhagen, circa 1752–1754

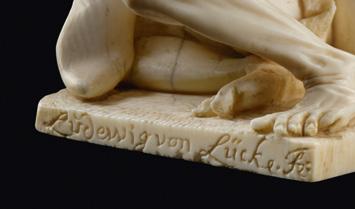

Signed ‘Lŭdewig von Lücke.Fe:’ on the right-hand side of the base; the hand guard of the sword bears an interlaced monogram ‘F5’

Provenance: Collection of Henry Makins, London, 1930s, thereafter by descent; sold at Christie’s London, 2 July 1997, lot 159 (erroneously as Friedrich Christian Kurfürst of Saxony); Collection Emminger, Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Related Literature: Hein, Jørge. Ivories and Narwhal Tusks at Rosenborg Castle, Catalogue of Carved and Turned Ivories and Narwhal Tusks in the Royal Danish Collection 1600–1875, Copenhagen 2018.

Kappel, Jutta. Elfenbeinkunst im Grünen Gewölbe zu Dresden. Geschichte einer Sammlung. Wissenschaftlicher Bestandskatalog – Statuetten, Figurengruppen, Reliefs, Gefäße, Varia, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden 2017.

Becher, Beate. ‘Lücke Ludwig’ in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 15 (1987), pp. 448–49 (online version) https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd132605872.html

Theuerkauff, Christian, ‘Johann Christoph Ludwig Lücke, Ober-Modell-Meister und Inventions-Meister in Meissen, Ober-Direktor zu Wien’ in: Alte und Moderne Kunst, issue 183, Vienna 1982, pp. 21–32.

Theuerkauff, Christian, ‘Einige Bildnisse, Allegorien und Kuriositäten von Johann Christoph Ludwig Lücke (um 1703–1780)’ in: Alte und Moderne Kunst, issue 174–75, Vienna 1981, pp. 27–38.

Lier, Hermann Arthur,‘Lücke Ludwig’ in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (1906), (online version) https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd132605872.html This allegory of a ruler depicts Frederik V (born 1723 in Copenhagen) who bore the title ‘King of Denmark and Norway, Duke of Schleswig and Holstein and Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst’ from 1746 until his death in 1766. Its similarity to contemporary portraits leaves no doubt as to its attribution. A further clue can be found in the monogram ligature on the sword’s handguard. Frederik V reputedly wore the Order of the Dannebrog on his chest. However, on this statuette, it is not the Order of the Dannebrog that is shown but the Order of the White Eagle that was worn during the same period by the Electors of Saxony.

It is very probable that Lücke wanted to offer his services to the Court of Copenhagen through the presentation of this figure. Having inadvertently carved the order – the all-so-important ruler’s symbol – incorrectly, this work was presumably rejected and did not remain in Copenhagen.

The monarch is stepping over a figure crouching on the ground, his gaze directed into the distance. He is dressed in full regalia. Between the folds of his ermine-lined cloak, the star-shaped order is visible. He is carrying a sword at his side that bears the monogram ‘F5’, for Frederik V, on the handguard. The Danish kings always used the first letter of their name with the respective numeral as their monogram.

It seems as if the monarch does not even notice the uglylooking, unclothed old woman lying at his feet. This figure, the antithesis of the good-looking, strong ruler is, in fact, an allegory of envy. The old woman has torn her own heart out of her chest and is holding it in her hand as she takes her last breath.

28

Signature on the base

Monogram ‘F5’, for Frederik V, on the hand guard of the sword

Frederik V 1746–1766, 1/48 Thaler, 1762, Oldenburg

28

The group of figures is signed ‘Lŭdewig von Lücke.Fe:’ on the base. Johann Christoph Ludwig Lücke, a sculptor and carver of small figures, was born around 1703, probably in Dresden. He worked as an apprentice under Balthasar Permoser or the ivory carver Carl August Lücke the Elder, who was probably his father or uncle. Afterwards, as a journeyman, Lücke went to France, Holland and England. In 1728 he was called to work as a modeller at the Meissen porcelain manufactory and, from 1729 onwards, worked independently as an ivory carver in Dresden. At this time at the latest he was in contact with Balthasar Permoser. In the following years Lücke repeatedly applied for the position of court sculptor in Dresden without success. Nevertheless, he successfully sold his works, including ‘Die Zeit hebt die gesunkene Kunst’ (Time raises foundered art; 1736)1 and an ivory crucifix (1737). In a description of the ‘Grünes Gewölbe’ (Green Vault) from 1739 it was ‘praised to the highest degree’.2 Today, it is one of the major exhibits in the Dresden ivory collection.

Evidence exists that Lücke subsequently worked in various different places, including Schwerin, Saint Petersburg and Hamburg. He worked once again as a porcelain modeller in Vienna and Fürstenberg. The search for commissions and a permanent position led to a certain restlessness.

Thanks to the assistance of Count Waldemar Schmettau,3 Lücke left Hamburg for Copenhagen in 1752. For an annual salary of 600 thalers and the title ‘Ober Kunst Cämmerier’ (court master of the arts) he was to produce porcelain that was to be ‘at least as good as that of Meissen’.4 However, the samples of his work were not sufficiently appreciated and once again nothing came of a permanent appointment.

1 Signed I.C.L. Lücke, dated 1736, SKD, Grünes Gewölbe,

Dresden, inv. no. II 337, Kappel 2017, p. 335f 2 Kappel, op. cit., p. 358 3 Theuerkauff, op. cit., p. 28 4 Ibid.