12 minute read

10 Two Wings of an Altarpiece with Scenes from the Life of the VirginMary

Fig. 1. Simone Bianco, Profile Portrait of a Woman, white marble, Galleria Estense, Modena, inv. no. 2045

Advertisement

Fig. 2. Palma il Vecchio (Serinalta/Bergamo c. 1480–1528 Venice) , Young Woman in Blue Dress with Fan, circa 1512–14, poplar wood, 63.5 x 51 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna The lower border of the relief stone, similarly worked in both cases, also speaks in favour of this. To date, however, it has not been possible to compile a chronology for the few works. This was attempted by Kryza-Gersch who, however, notes: “Although the chronology proposed so far does not seem unreasonable, a word of caution should be added. As already pointed out by Anne Markham Schulz, Simone must have been able to switch his style according to the nature of his commission.”5 It is certain that Bianco started his activities before 1512 and was still alive in 1553. He received many commissions and was highly skilled in making works to meet the wishes of collectors. That this relief was created around 1530, when the artist had reached the peak of his career, is highly plausible.

The relief discussed here is also very much in keeping with Simone Bianco’s style that oscillates between all antico, on the one hand, and contemporary, on the other. Interestingly, Bianco’s idealised portraits of women, unlike his busts of men, for example, do not depict heroines from Classical Antiquity. Neither are they contemporary portraits. The style of Bianco’s work could be described as hybrid – moving little by little towards individualised portraiture from the certainty of the pictorial tradition of Antiquity. Or else his busts are creations in the style of ‘beautiful Venetian women’ to whom Palma il Vecchio (fig. 2), Titian and Paris Bordone paid homage in their paintings, executed at the same time. Giorgione established a paradigm for this new genre of female portraiture in Venetian painting with his Laura in 1506. The identity of his model remains uncertain; the ideal of female beauty being celebrated, pars pro toto, in his depiction. Our unknown beauty with her classical profile also fits perfectly into this artistic category.

We are grateful to Dr. Anne Markham-Schulz who confirms the attribution to Simone Bianco on the basis of photographs. She has never seen the relief first-hand and knows it only from photographs. She thinks that Bianco was the first sculptor who kept a shop with reliefs for sale and that his young girls met with great success.

5 Kryza-Gersch, op.cit., 2013 p. 82

18

Ewer with Bacchanal and the Triumph of Sea Gods

EWER WITH BACCHANAL AND THE TRIUMPH OF SEA GODS

France (Limoges)

Third quarter 16th century

Signed I.C., inscribed with the inv. no. ‘G-R 772’ in red ink on the underside

Grisaille and camaieu enamels Height: 27 cm

Provenance: Collection of Baron Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, sold at auction at Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, 13 April 1950, after the restitution to the heirs of Goldschmidt-Rothschild in 1949; The Ernest Brummer Collection: Auction sale, 16–19 October 1979, Zurich, Galerie Koller & Spink & Son (sale no. 257, cat. pp. 396–399); Private American Collection.

Literature: The Ernest Brummer Sale, auction sale, 16–19 October 1979, Zurich, Galerie Koller & Spink & Son (sale no. 257, cat. pp. 396–399).

Kjellberg, Pierre. ‘Limoges, Fontainebleau’, Connaissance des arts, July 1979, no. 329.

Works of Art from the Estate of the Late Baron Max von Goldschmidt-Rothschild; Auction sale 13 and 14 April 1950, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, sale no. 137, cat. p. 7.

Related Literature: Wardropper, Alan. Limoges Enamels at the Frick Collection, New York 2015.

Weinhold, Ulrike. Maleremail aus Limoges im Grünen Gewölbe, exh. cat., Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 17 September 2008–18 January 2009, Munich/Berlin 2008.

Caroselli, Susan L. The Painted Enamels of Limoges: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, L.A. 1993. This finely chased copperplate ewer with grisaille painting is an outstanding work of Limousin enamel produced in the 16th century. The signature ‘IC’ is inscribed on the inner surface of the double-walled spout.

As there are certain stylistic differences between the individual elements it is now assumed that the monogram ‘IC’ is not the signature of one particular artist but maybe the mark of a workshop. It is also possible, that it refers to several enamellers with a similar or the same name who were active in the second half of the 16th century and later.1

The ovoid body of the delicately executed ewer comprises two parts, joined by a ring in between. The narrow neck on the upper half with its curved lip at the spout, is also chased. A conically shaped foot gives the object stability; the widely arched handle ensures the necessary functionality.

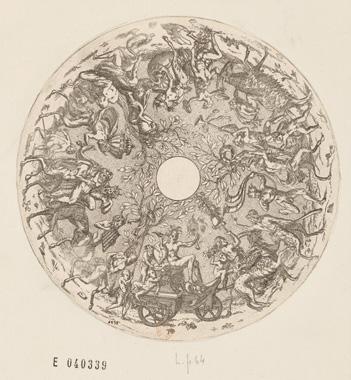

Thematically, an exuberant bacchanal dominates the ewer’s decoration. It was modelled on the engraving ‘The Triumph of Bacchus’ (c. 1546, fig. 1) by the French architect and draughtsman Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (before 1520–1585/86) that is one of a widespread series of designs for vessels. The composition, originally conceived as a decoration for a bowl or basin, has been transferred here to the main body of the ewer, albeit in a more compact style and with several modifications made by the enameller.

A boisterous celebration is depicted: Silenus, drunk and exhausted from all the revelry, is seated on a donkey and supported by two elderly satyrs; another is holding Silenus’ mantle, dynamically caught in motion, that is about to slip from his shoulder. Other satyrs are playing the syrinx and trumpet. A small child and a billy goat form a second group of mounted characters. Through the light colour of the skin the figures are decoratively set off against the dark enamel background that is brightened by bushes highlighted in white and gold.

The shoulder of the ewer is decorated with a number of frolicking aquatic creatures based on ‘The Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite’, another work by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau. 18

Fig. 1 Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, vol. VI, fol.30. ”Cortège de Silene et du jeune Bacchus, projet du fond de coupe“, circa 1546, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, MFILM E 040339. L.p. 64.

18

A group of mythical monsters is splashing around in a skillfully depicted foaming sea of white, wavy lines on a dark background. Winged stags, a bull ridden by a fabulous masked creature with wings, a female centaur, a woman with bats’ wings, a Triton, a Nereid and another mythical creature are dancing on the waves.

The neck of the ewer, the central bead and the foot of the object are decorated with large acanthus leaves and golden tendrils. The ornamentation on the underside of the handle comprises stylised golden cornflowers on a dark ground; the contrasting white enamelled upper surface bears a black linear decoration in the form of a twisted cord.

Enamel objects with decorative grisaille painting are typical of the ‘IC’ workshops. Figurative and decorative elements are applied in white on a dark ground with delicately differentiated areas of light and shade. Grisailles were left monochrome or, in this case, coloured by pigments applied on top, creating the illusion of a bas-relief.

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, whose engravings provided the basis for the ornamentation on the ewer, strongly influenced Limousin decoration in the 16th century with his graphic designs. Stylistically these belong to the Fontainebleau School, a French variation of Mannerism. Thanks to printmaking, these popular artistic models soon became widespread.

Our ewer belongs to a large group of very similar vessels from the workshop of the monogrammist ‘IC’ that are characterised by the same decorative principle.2 At the time they were made, enamel objects of this quality were considered absolute luxury items, intended less for everyday use and more as decoration in a nobleman’s palace or a wealthy burgher’s house. Several enamellists from Limoges even created portraits for the French royal household. Today, enamel objects bearing the signature ‘IC’ can be found in international museum collections including the Louvre, the Frick Collection and the Walters Art Museum.

1 Weinhold, op. cit., p. 114 2 Ibid., p. 11

Damascene Mirror

19

DAMASCENE MIRROR

Italy, probably Milan

Second half 16th century

Steel damascened with gold Height: 30.5, width: 20 cm

Provenance: Oscar Bondy Collection; Private American Collection. This mirror is an excellent example of a rarely preserved Italian furnishing made of steel, from the latter half of the 16th century. Damascened in gold, the front, back and both sides of the rectangular mirror frame are adorned with elaborate, GrecoRoman inspired foliage and geometric decorations characteristic of the decorative arts of the period. In the centre of the cornice crowning the mirror, a small figurine of a putto extravagantly flourishes a laurel wreath, a symbol of victory, success and achievement. The mirror decorations have many similarities with the damascened plates on the casket from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1).

The technique of damascening is believed to have originated in the Middle East and was named after the Syrian city of Damascus. While technically quite demanding and time consuming, the method facilitated a greater variety and complexity of designs, commendatory of both the object’s aesthetic splendour and the accomplished skills of its maker. Damascene surfaces are lavishly and often colourfully decorated, while also being very durable. The technique consisted of the inlaying or encrusting of precious metals onto iron or steel surfaces. In Europe, the most common process involved cross-hatching the iron surface using files to create puckered edges onto which the craftsmen could apply gold and silver leaf or wire that was then burnished flush with the surface.

During the late Renaissance period the technique became particularly associated with Milanese metalworking, known for producing elaborate armour for the noblemen of Europe, as well as high quality iron and steel furniture and decorations. The northern Italian city of Milan was one of the most populous and wealthy western cities of the time. Its continuous prosperity and growth in the 16th century occurred in spite of periodic plague epidemics, as well as frequent battles during the so-called Italian wars. Vastly subsidised by Sicily, Naples and Spain throughout these turbulent times, the city maintained and even increased its importance in a political and economic sense, becoming a synonym for high skilled manufacturing and the production of luxurious goods in any material and supplying highly praised products to every European court.

Fig. 1. Casket, Italian, probably Milan, circa 1545–47, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no. 56.139a,b

19

20

Crucifixion Group with Christ and Mary Magdalene

CRUCIFIXION GROUP WITH CHRIST AND MARY MAGDALENE

Southern Germany

Late 16th/early 17th century

Boxwood Heights: Christ: 26 cm, Maria Magdalene: 14.3 cm

Added nipple inserts on figure of Christ and buttons on Mary Magdalene’s garment

Related Literature: Giambologna. Triumph des Körpers, exh. cat., Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, 27 June–17 September 2006, Milan 2006, pp. 162–65.

Silberhirsch und Wunderprunk in der Kunstkammer Würth, exh. cat., Kunsthalle Würth, Schwäbisch Hall, 18 May 2015–10 January 2016, Passau 2015, pp. 168–169. The motif of the sinner Mary Magdalene kneeling before the Cross was very popular, especially in southern Germany. This is due to one magnificent example of such a group of figures. The famous Flemish-Italian Baroque artist Giambologna created several crucifixes that were to influence sculpture from the 1570s onwards. One is to be found today in the Jesuit church of Saint Michael’s in Munich. He executed the crucifix in 1594 in Florence. Giambologna’s German master pupil, Hans Reichle (Schongau 1565/70–1642 Brixen) added the figure of Mary Magdalene in 1595. Her posture is dramatically moving and her imploring gaze looks up at Jesus’ face (fig. 1). She symbolises the faithful sinner seeking redemption.

A present from Ferdinando de‘ Medici to William V, Duke of Bavaria, the crucifix was sent from Florence to Munich. It was intended to decorate William’s projected tomb in the Jesuit church that was built from 1583 onwards. The project, however, was never completed. Only the crucifix with the mourning figure of Mary Magdalene was installed in Saint Michael’s as a figurative group. Not only the Jesuits marvelled at this masterpiece there which soon became well-known beyond Munich. Numerous artists visited the church to look at the work that was praised for ‘the beauty of its craftsmanship and masterly execution’.1 Another small Crucifixion group with Mary Magdalene, circa 1620, Southern Germany (Augsburg or Munich) is in the Sammlung Würth. (fig. 2)

Jean de Boulogne who came from Flanders travelled from Doway to Italy where he called himself Giovanni da Bologna. While in the service of the Medicis he created the Rape of the Sabine Women – a group of figures now on the Piazza della Signoria in Florence. The group also became a model for later sculptors just like his depiction of Christ that reflects the characteristic Classical ideal of the human body. His small bronze crucifixes, made together with his workshop under Antonio Susini, became widely sought-after among art collectors.

20

1 Cf. exh. cat., Vienna 2006, op. cit., p. 164 and note 26

Fig. 1. Crucifixion group in the Jesuit church of Saint Michael’s, Munich; Christ (1594) by Giovanni da Bologna (1529–1608); figure of Mary Magdalene (1595) by Hans Reichle (1565/70–1642), detail The sculptor of our crucifixion group certainly came from the southern German region. His work bears a characteristic individual style. One particular feature is the fine execution of detailing such as that on Mary Magdalene’s garment and her hair, as well as the tears on her face. The figure of Christ has notable ornamentation on the loin cloth and in the treatment of the hair and beard. Even the hair under his arms is carved; the nipples, however, have been inserted separately. To date it has not been possible to identify the sculptor.

Fig. 2. Crucifixion group with Mary Magdalene, circa 1620, Southern Germany (Augsburg or Munich), boxwood figures, walnut veneer pedestal, ebonised, 74 x 32 x 14 cm, Collection Würth, inv. no. 9357

20

Christ Crucified Georg Petel

(ATTRIBUTED TO)