THE AMAZON CREEK LITTERSHED

Fighting Plastic Pollution in Urban Waterways

Fall Studio 2022

Jennifer Ginn, Lainey Everly, Simon Allen, and Trevor Hattabaugh

Jennifer Ginn, Lainey Everly, Simon Allen, and Trevor Hattabaugh

Fall Studio 2022

Jennifer Ginn, Lainey Everly, Simon Allen, and Trevor Hattabaugh

Jennifer Ginn, Lainey Everly, Simon Allen, and Trevor Hattabaugh

This project focuses on the distribution of litter as a pollutant along urban waterways and it uses local design solutions to address litter and pre-littering behavior. We used point-in-time data collection, analysis of zoning, and proximity to key features such as commercial buildings to map litter accumulation with a focus on single use, plastic items. We studied the Amazon Creek in Eugene, Oregon to determine design solutions for addressing litter pollution along heavily modified urban waterways. We chose to focus specifically on plastic litter because of the prolonged and multi-level impacts that it will have on ecosystems and the human experience.

This studio work was conducted on Kalapuya Ilihi, the traditional indigenous homeland of the Kalapuya people. Following treaties between 1851 and 1855, Kalapuya people were dispossessed of their indigenous homeland by the United States government and forcibly removed to the Coast Reservation in Western Oregon. Today, descendants are citizens of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians of Oregon, and continue to make important contributions in their communities, at UO, and across the land we now refer to as Oregon. We express our respect for all federally recognized Tribal Nations of Oregon. This includes the Burns Paiute Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians of Oregon, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, the Coquille Indian Tribe, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, and the Klamath Tribes. We also express our respect for all other displaced Indigenous peoples who call Oregon home. We thank the Native Strategies Group for a portion of our statement.

SECTION ONE: Our Plastic Problem...................................

SECTION TWO: Addressing Plastic Pollution...................................

SECTION THREE: Local Design Solutions...................................

PAGE 4 PAGE 8 PAGE 12

Ignacio Lopez Buson

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. “Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made.” Science advances 3.7 (2017): e1700782–e1700782. Web.

Keep America Beautiful. (2021, May). Keep America Beautiful 2020 National Litter Study Summary Report.

Person by Icon Box, Info Poster by Kiran Shastry, Duck by bmijnlieff, Plastic bottle by Imam, Plastic bag by Felipe Perucho, Plastic straw by Lucas Helle, Fork by Nico Ilk, Plastic cup by Mike Barbetta, Candy wrapper by Maxim Samos, Salamander by Andrea Novoa, String by Carol Costa, Bridge Jenny by Vectors Point, Coke bottle by Tom Fricker, House by AFY Studio, Store by AomAm, Garbage truck by Dennis Chatham, Diffuse by Stephen Plaster, Skyline by Shiva Narrthine, Houses by kareemov1000, Bridge by LAUREN, Cigarette Butt by Stan Diers, QR Code by Mohammed Mb all from Noun Project

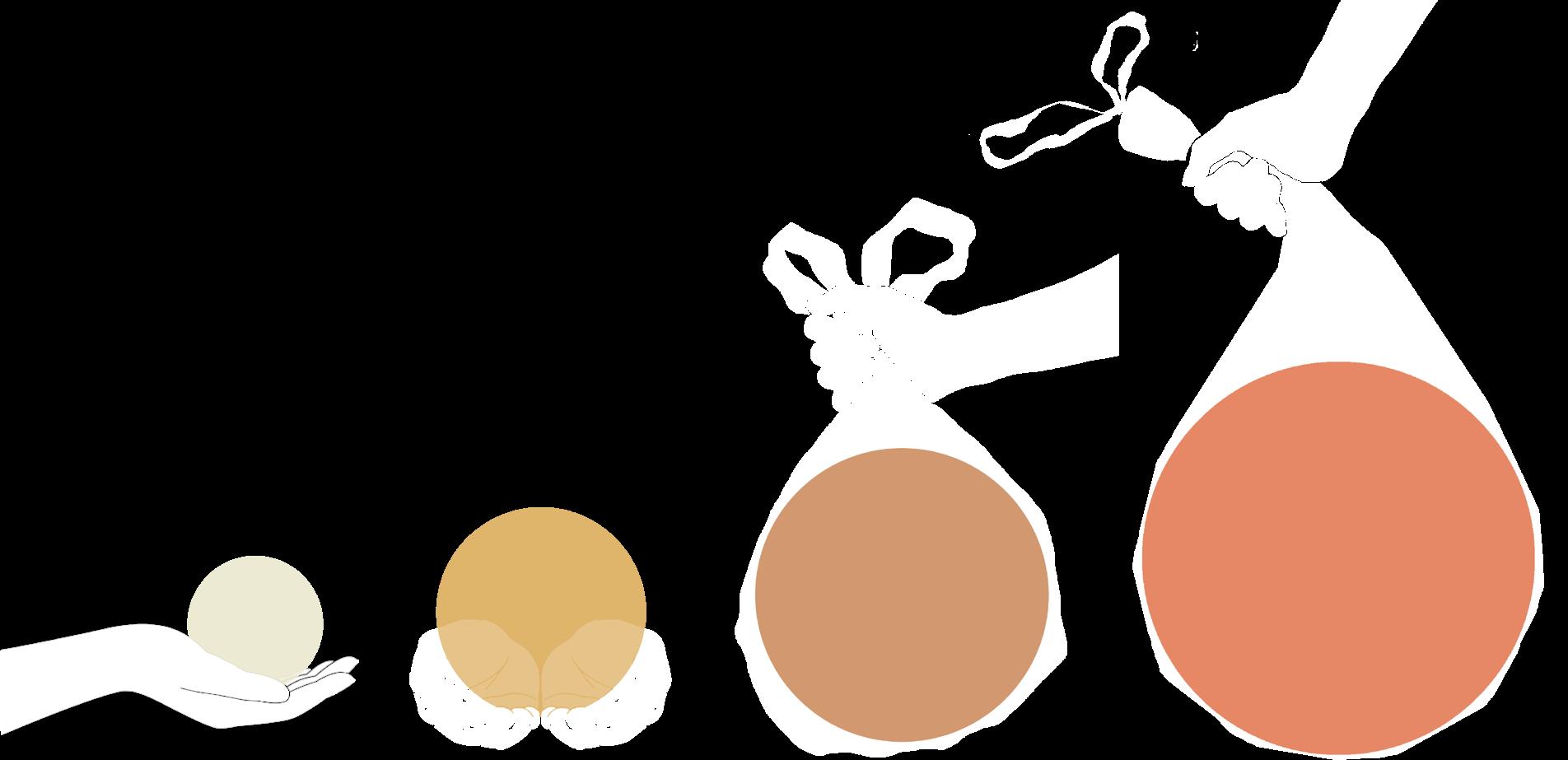

6.3 billion metric tons of plastic waste have been produced since the 1950s, 79% of which has been discarded and is accumulating in landfills or our environment (Geyer et al., 2017).

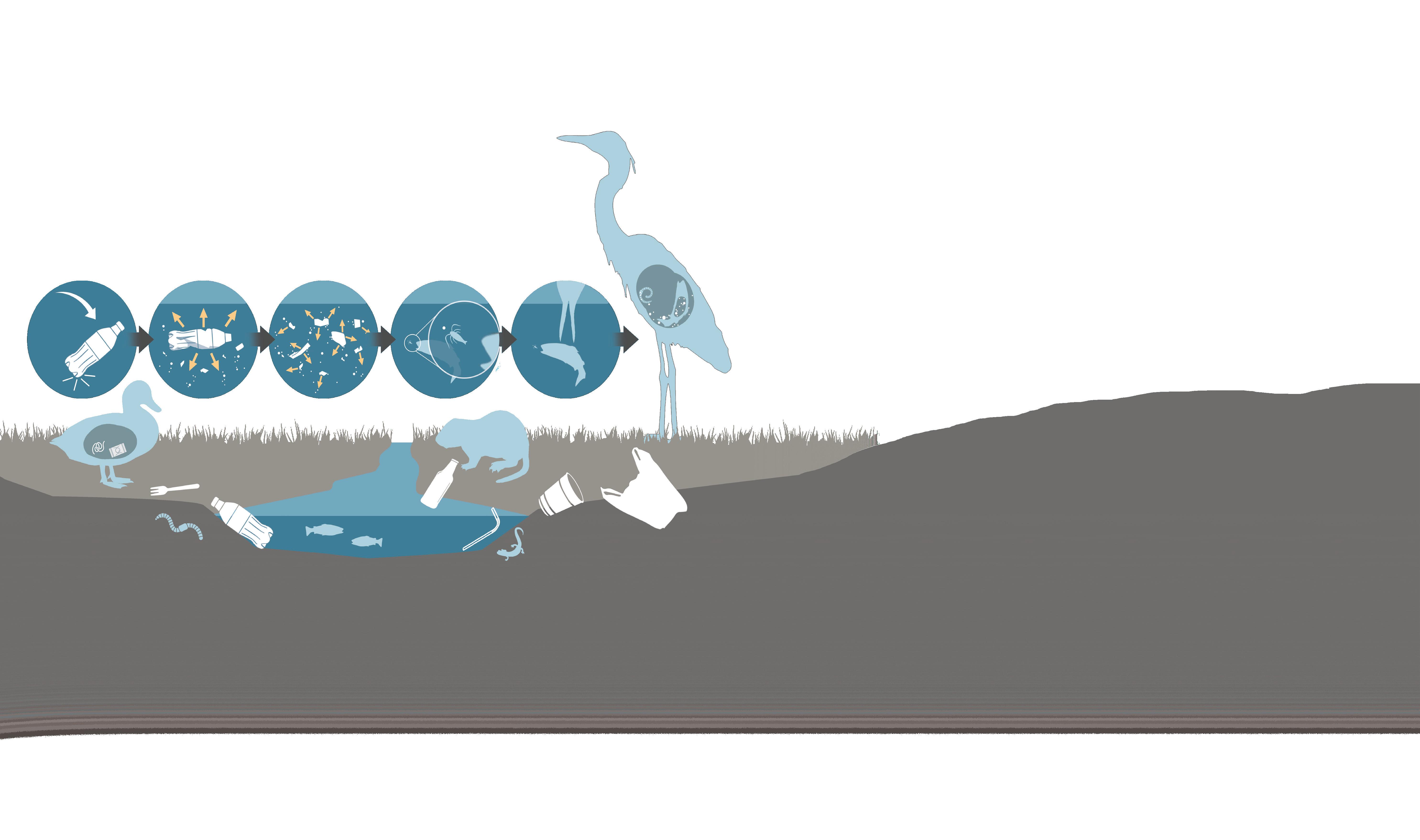

Plastics impact ecosystems through chemical leaching and as physical matter in the environment. It is ingested by animals, causing gut blockage, poor appetite and starvation, and internal lacerations or lesions. It can also obstruct wildlife through entanglement. Plastics are composed of several chemical components - many of which are still unknown to us. Almost all studied plastics leach toxins that have been proven harmful to human health. Plastics contain additives, such as plasticisers, stabilizers, and flame retardants which are made of harmful chemicals such as BPA, PVC, Antimony, and Phthalates. These impact an organisms’ abilities to reproduce, regulate hormones, fight infections, metabolize, and mitigate blood toxicity, and have been shown to encourage tumor formation and exacerbate asthma. When plastic litter breaks down into micro and nano particles, they can more readily infiltrate the food web, bioaccumulating in a wider variety of organisms, and the greater surface area of multiple, smaller particles leads to an increase of leached chemicals.

Litter is waste that is removed from local trash collection and recycling systems and is discarded in a socially inappropriate areas. Keep America Beautiful provided the first nationwide study on litter in 2020 and estimated there are about 26 billion pieces of litter along American waterways. Plastic-film packaging is the second biggest contributor to litter in the environment (after cigarettes).

Factors were identified that increase litter accumulation. One factor was resting areas like benches and bus stops. Through research and observation, these typically had no trash cans, or if they did they were overflowing. Another factor was proximity to collective use land, meaning parks, schools, and commercial hubs, particularly businesses that supply single-use items. Clearings by the creek with an added factor of privacy also had higher severity of litter instances. Bridges, fences, and canal corridors all increased the frequency of litter as well.

4These illustrations are representational of littering behaviors and circumstances along the Amazon creek where key instances of littering were localized. Ties can be made between the presence of litter and proximity to specific municipal zones, spatial use and site, appearance, and the relationship between the local environment and the creek canal.

1. Seating with no close access to waste disposal

2. Trash deposited from upstream in close proximity to commercial zone, clearing next to creek, no nearby waste disposal

3. Dense commercial, urban zone, concrete canal and chain fencing , lack of visible ecological connectivity, highly trafficked open spaces

4. Chain fence spatial divide, bridge crossing, intersection, proximity to commercial zone

Litter pollution in the environment is a positive feedback loop, which means littering behavior is more likely to occur where littering has already happened. Beautifying the creek corridor, engaging communities through education and awareness building, increasing community stake in protecting the Amazon Creek, and providing increased access to waste infrastructure are primary ways that this master plan seeks to disrupt the local litter feedback loop. Solutions have to be responsive and proactive, meaning both the existing litter feedback loop and pre-littering behavior need to be addressed.

•

Litter

•

• Education/outreach

•

•

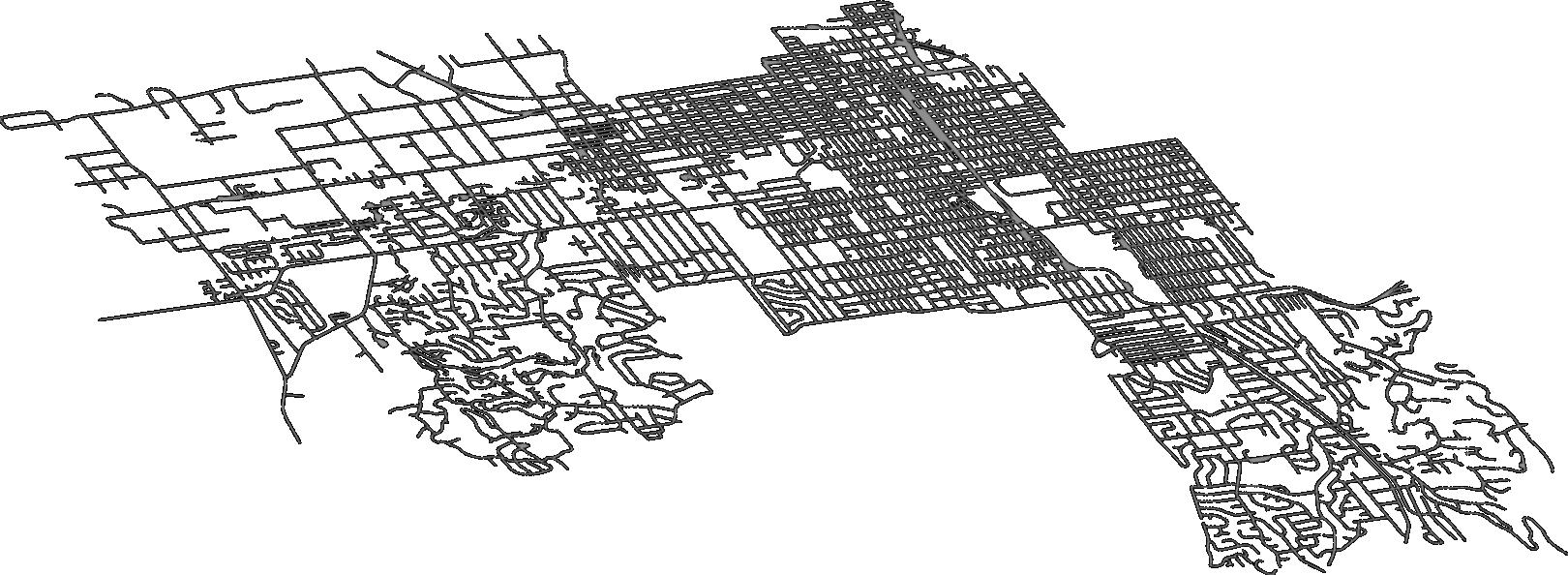

From analysis of spatial litter data, specific locations were selected for this master plan. Actions undertaken within each layer of this master plan are explored in more detail on page 10. Twelve neighborhoods that intersect with the Amazon Creek form the foundation of policy implementation. The elements of this master plan address the litter feedback loop through education, community engagement, infrastructure improvement, and policy.

Participating Neighborhoods

West Eugene Community Organization

Churchill Area Neighbors

Far West Neighborhood Association Jefferson Westside Neighbors

Downtown Neighborhood Association 6 University of Oregon Campus

South University Neighborhood Association School Grounds

10 11

adjacent to the creek 8 9 12

Friendly Area Neighbors Amazon Neighbors Association Southeast Neighbors

Litter and plastic consumption are deceptively complex issues impacting our shared experience. Educating the public about litter and the waste system, supporting community stewardship, reinforcing waste infrastructure, and creating responsive local policies form a comprehensive plan to address the mental and physical origins and outcomes of litter pollution. Goals will be achieved by implementing 12 specific actions along the Amazon Creek in order to reduce and ultimately eliminate plastic pollution. Observational data informed these goals which work to disrupt existing litter feedback loops. These goals and their colors correspond to the colored areas on the master plan map.

Goal: to educate people about the impacts of plastic as a pollutant within the environment

Goal: to enhance individuals sense of community and stewardship

Infrastructure Goal: to create permanent fixtures that collect waste and deter littering

The 12 proposed actions meet multiple goals, because plastic litter is a multi-faceted issue requiring comprehensive solutions. Some aspects of each goal will take longer than others to achieve, and this timeline represents the timing of implementation, data collection, and revision strategies for each goal. Litter is a complex problem impacting our shared landscape, but the source is ultimately individuals. Solutions to litter pollution have to address both access to infrastructure and community psychology.

The timeline for implementing these 12 actions begins in the first year, starting with policy and waste infrastructure. Data collection on waste collection frequency will begin in the first year, and will be used to inform infrastructure optimization over the subsequent years. Community engagement and education programs can see their beginnings in the first year and ideally these programs can develop dynamically over the course of five years. The actions of this timeline can be refined and redirected as the city of Eugene sees what works to reduce litter along the Amazon Creek, what needs will change over the next five years, and what still needs to be addressed.

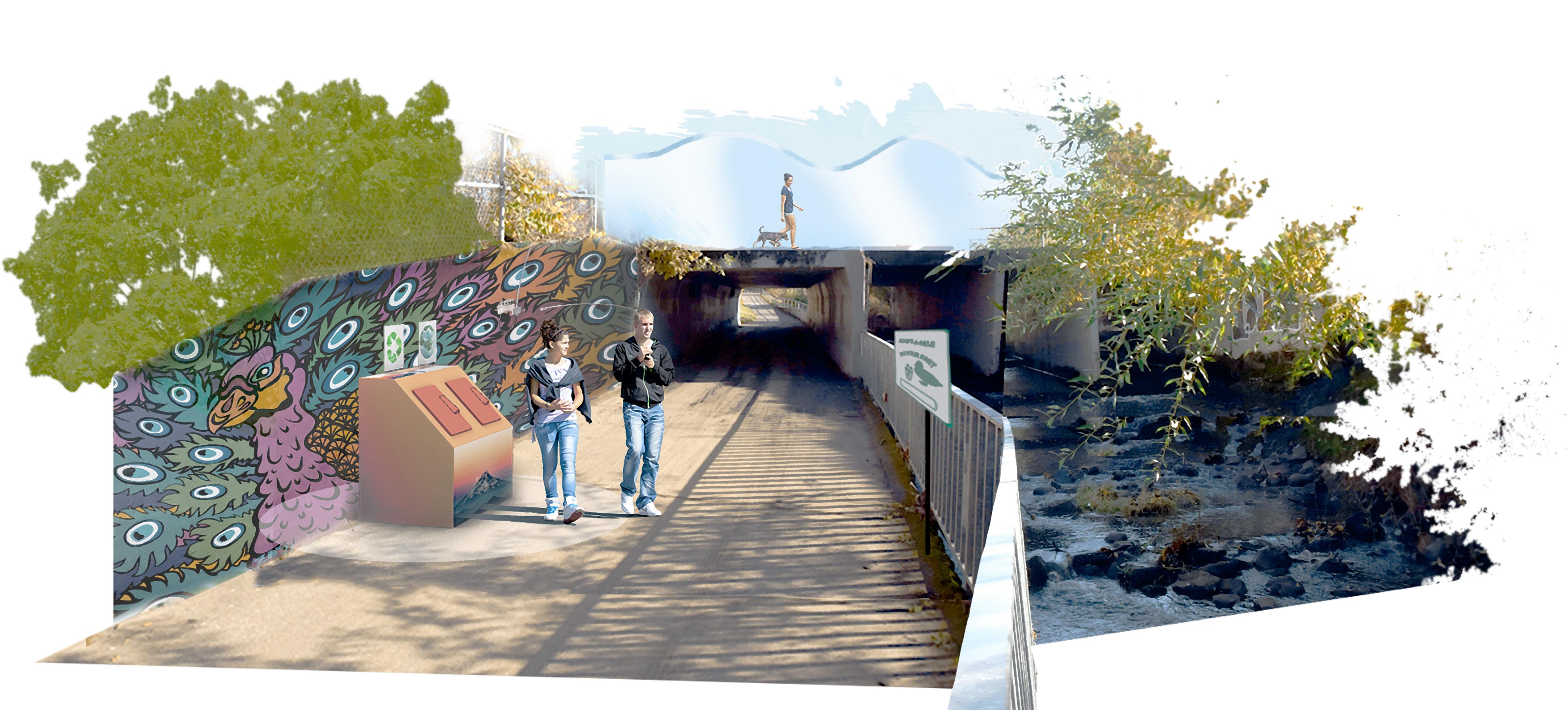

This render shows proposed infrastructure remediations for bridges that intersect the Amazon Creek. The glass partition allows people to see the creek below but deters opportunistic littering over the edge. The mural wall beautifies the bridge intersection and builds community ownership of the creek.

Murals reflecting community identity by local artists

Waste bin at bridge intersection

Adopt-a-mile program

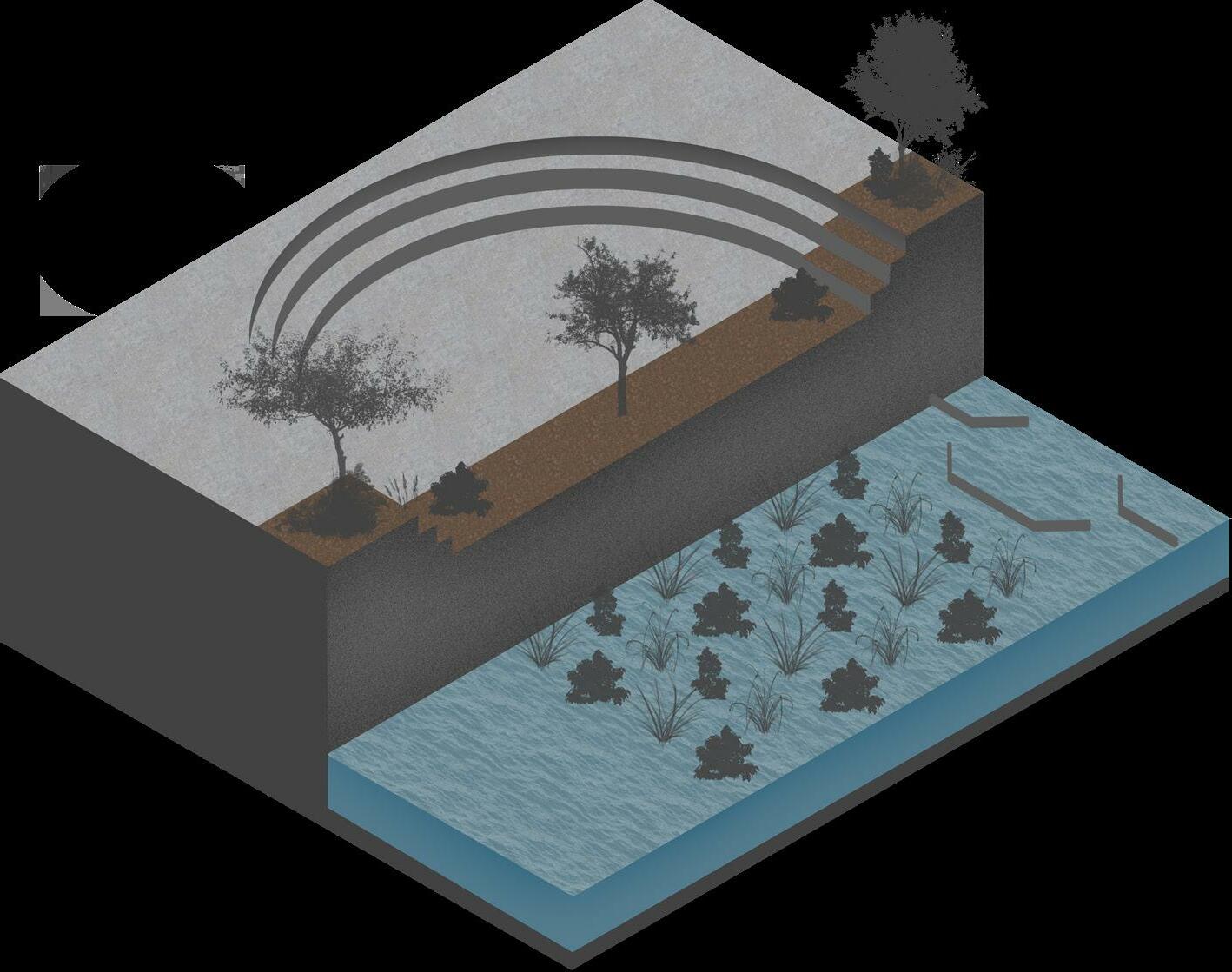

This render illustrates an amphitheater that would be constructed adjacent to heavily-trafficked walkways close to commercial and collective-use zones, with preference given to areas in proximity to a school. These will be implemented along the waterway in a variety of ways depending on whether the water system is channelized or not. It serves to beautify and restore the space through toxin- remediating plantings, and also includes a plastic catchment system. The amphitheater would serve as an educational sphere to engage individuals with the creek, especially portions that are channelized and funneled through urban spaces with little public access.

Waste containers will be installed within a quarter mile of every bridge

“This trash can needs service”Specialized waste bin Amazon Creek Section adopted by the Amazon Neighborhood

Litter is everywhere - especially in urban settings. This pollution has a profound, if statistically underrepresented, impact on human experience and the ecosystem, and has significant, long-term effects on the presence of toxins in the environment. Given that 70% of the global population is expected to be living in urban communities by 2050, we need local strategies to efficiently choose areas for litter intervention.

Addressing this issue requires a varied design approach and our research shows that solutions should take into account local conditions affecting the distribution and accumulation of litter. This requires further studies involving site-specific data collection and analysis to identify local patterns and issues as they relate to plastic litter pollution. Additional data should be acquired through assessment of zoning, existing waste infrastructure, and the physical relationships between water bodies and their surroundings. With the implementation of these methods and investigations as outlined in this study of the Amazon Creek, plastic litter pollution can be addressed in any urban setting through informed design solutions.