11 minute read

Articles Mapping out a career in glaciology Julian Dowdeswell

Mapping out a career in glaciology

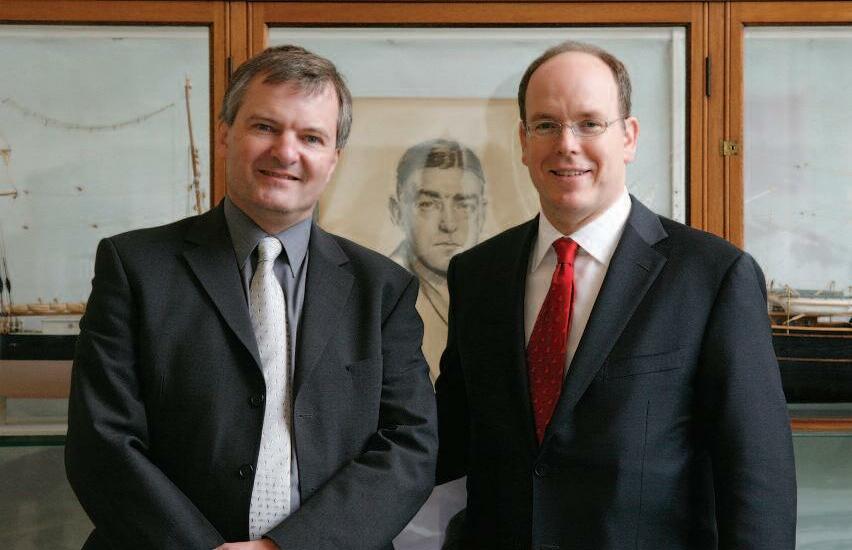

An interview with Professor Julian Dowdeswell, former Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, and Brian Buckley Fellow in Polar Science at Jesus College1

Advertisement

The past year has been one of surprises for Professor Dowdeswell. He learned that an Antarctic bay would be named in his honour and, on a personal level, he discovered the joy of grandparenthood and having more time with the family. Our Editor asked about his career so far, and his plans for further travel, research and teaching.

How and when did you become interested in glaciology?

As a child I loved maps, a passion that continued as an adult – as a young father, I’d pour over Ordnance Survey and road maps in the car waiting for my daughter to come out of ballet class. This interest in maps led me to Geography, and I was encouraged at school by excellent and enthusiastic teachers to apply to Cambridge. Coming up to Jesus 1977, I was taught by scientists from the Scott Polar Research Institute as part of the Geography degree, and I often sought out the quiet space of the Institute ’ s Polar Library. I became fascinated by the polar regions and as an undergraduate I put together a small expedition to study a part of the Vatnajökull ice cap in Iceland. One of the expedition patrons was Sir Alan Cottrell, who was Master of Jesus at the time. Another Fellow of the College, Dr Stan Evans, provided training in survey techniques and my Director of Studies, Dr Robin Donkin, applied his usual rigorous eye to my proposal. From the observations gathered on this expedition I wrote my first scientific paper, which was published in the Journal of Glaciology in 1982.

Tell me about your recently published research

In 2019, I was Chief Scientist on the Weddell Sea Expedition off the eastern Antarctic Peninsula, in the area where

Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance was crushed by ice just over 100 years earlier. We aimed to investigate the ice shelves (the seaward extension of inland ice sheets) around the Weddell Sea and, in particular, the Larsen C Ice Shelf from which a giant iceberg broke off in July 2017. We also hoped to locate and survey the wreck of Endurance. Although we didn ’t find the Endurance (it was located in early 2022), several articles have been published recently about our scientific work, including one about the rapidity of ice-sheet retreat in Science. 2 A further paper in Nature Geoscience used satellite imagery from the past few decades, and the latest ocean and atmosphere modelling predictions, to study the spatial and temporal patterns of ice-shelf change east of the Antarctic Peninsula. 3 We found that portions of the ice shelf were in their most advanced position since satellite records began in the early 1960s. That’ s counter to what happened in the late 1990s years or so, when ice shelves collapsed catastrophically into the sea. Changes in atmospheric circulation mean that more sea ice is being carried by the wind to the coast, which is acting to buttress the ice shelves so that they ’ re much less prone to collapse.

Measuring ice shelves is important because the presence of these floating extensions of the inland ice sheet help to buttress the ice sheet against collapse. If ice shelves collapse, ice flows more rapidly to the coast of Antarctica, more mass is lost as icebergs, and an increment is added to global sea level. Conversely, ice-shelf growth slows the flux of ice to the sea, putting a break on the ice-sheet contribution to global sea level. Thus, the fate of ice shelves is highly relevant to humankind more generally through its effect on sea-level change.

How does your research make you think about the environment and sustainability?

One of the exciting things about glaciology over the past 40 years is that it’ s gone from being seen as a somewhat quirky, although intellectually challenging, subject to becoming absolutely mainstream in terms of measuring environmental change. This shift in attitude started in the mid-1990s, around the time that the first

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report was published and shone a spotlight on the importance of the icy world as a driver of global climate change. At that time, I was approached by several NGOs to become an environmental advocate, but I chose to remain a scientist and to contribute by providing quantitative evidence on the changing cryosphere. This includes past and present rates of ice-sheet retreat and their influence on global sea level. It is becoming clear that the cryosphere is one of the most sensitive parts of the global climate system. Greenhouse gases are clearly the dominant reason for the global warming that we ’ ve seen in the past few decades; temperatures have risen by more than a degree Celsius relative to the 1960-90 mean.

I think most people are now more aware of climate change. I’ m active on both a personal and institutional level in trying to project the causes and implications of environmental change to humankind. The Polar Museum we have at the Scott Polar Research Institute, with its 50,000 or so visitors each year, provides wonderful opportunities to spread the message to wider audiences.

How is Jesus College doing for sustainability?

It's great to see Jesus College making progress with sustainability initiatives. The infrastructure of the buildings here makes it a complex and difficult job, but the installation of ground-source heating is excellent, both for the environment and for the College economy, too. Long term, it’ll be a win-win situation.

How do you feel about having an Antarctic bay named in your honour?

As part of my role as Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, I’ ve been a member of the Place Names Committee of the British Antarctic Territory, which names significant features within the Territory. At my last place names meeting after almost 20 years as Director of the Institute, the Chair announced that a bay on the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula would be named after me – it has a series of glaciers and a floating ice shelf feeding into it. I was grinning like a Cheshire Cat for the rest of the day. A place name has a certain permanence to it when you see it on a map. My father was just about to go into a care home at the age of 102, and it was a wonderful surprise when I told him. He was delighted.

What do you feel have been your greatest career highlights so far?

I love going to new places and trying to understand what is happening environmentally. It was particularly exciting to be one of the first people to go into the Russian High Arctic archipelagos after the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. It was an incredibly complicated mission and a very significant geophysics project, using Russian helicopters and radio-echo sounding equipment to measure the thickness of the ice. I arrived in Russia with several tens of thousands of US dollars in a money belt, as the banking system there had collapsed. Hiring helicopters was a strictly cash transaction. That research – because of the difficulties that remain in working in the Russian High Arctic – is still the definitive study of its kind.

I’ m also proud of the work I’ ve carried out around the eastern and north-eastern fjords of Greenland. The ice conditions make these areas very difficult to get to, even with modern ice-breaking research ships. I’ ve been there on a number of ships over a 15-year period, and we ’ ve managed to get into most of the fjords to read the geological records held in the seafloor sediments. I think that East Greenland is also the most beautiful place I’ ve ever visited. Its scale is stunning;

Sunset, eastern shore, Kangerdlussuaq Fjord, East Greenland. Credit: Julian Dowdeswell

you can be in one of the huge fjords there, 300km from the outer coast of Greenland, right up against the edge of the glaciers. The water is 1,500m deep, and the mountains are about 2,000m high. It’ s the biggest fjord system in the world.

Another aspect of my career that has been particularly rewarding has been to develop the field of glaciology in the UK. I established a new research centre for glaciology in Aberystwyth in 1994 with four supporting academic posts. I then went on to found the Bristol Glaciology Centre within the University of Bristol. Both centres continue to thrive, and the number of research posts have grown, which is wonderful. I was delighted recently to be made an Honorary Fellow of Aberystwyth University in recognition of my work in founding the Centre for Glaciology. It is also great to think of the doctoral and masters students that I have supervised, and also learned a lot from, in Aberystwyth, Bristol and Cambridge.

Over the past 20 years, my primary focus alongside my research has been my role as Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI), which was my undergraduate. SPRI is the oldest polar research institute in the world, and is a unique combination of polar research, teaching, the care of our wonderful historic collections of artefacts, documents and photographs, and public engagement through our Polar Museum. I’ m proud of the outreach and public engagement work of the museum, which is also projected through my own books. Together with Evelyn (a fellow polar scientist and also my wife), we have written children ’ s books on Captain Scott and Sir Earnest Shackleton that are used widely in schools today at Key Stage One. I’ll continue to write more because it’ s so important to showcase the environmental significance of the Arctic and Antarctic; I’ m working on a book called Arctic Islands at the moment.

What role do you play now at the Scott Polar Institute?

I retired as Director of the Institute in Easter 2021 after almost 20 years, and I’ll continue to support its combination of research, heritage and outreach post-retirement. I’ m still very involved in fundraising. We carried out a total refurbishment of our museum spaces about ten years ago, in time for the

centenary of the death of Captain Scott and his companions on their return from the South Pole in 1912. The museum now welcomes about 50,000 visitors a year including almost 20,000 school children. A series of large grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund and generous gifts from individuals (including Jesus alumnus Brian Buckley, 1962) supported the refurbishment of the Polar Museum and also enabled the purchase of a number of highly significant polar heritage items including, for example, all 1,700 glass-plate negatives taken by the renowned photographer Herbert Ponting of Scott’ s last expedition.

Importantly, earlier this year we received a major donation from Viking Cruises to fund in perpetuity a new Professorship of Polar Marine Geoscience in the Institute.

What’s next for you? Do you plan to visit Dowdeswell Bay?

The bay is quite a long way south, on the west of the Antarctic Peninsula below the Antarctic Circle, so I’ m not sure I’ll ever get there; however, plans are emerging for a possible visit in 2024! I do intend to travel to the polar regions again though. From a scientific point of view, I’d like to do more research in Antarctica and continue gathering data on the ice sheets. A number of tourist ships are now also being used as platforms for polar science, and I’ll take part in some of those exercises using a variety of geological equipment, backed up by satellite data sets. I chair the Research Advisory Group for Viking Expeditions and helped to design the laboratories on their two new ice-strengthened ships.

I plan to continue my work on public engagement with science. I also hope to complete my second book on the Arctic within the next year or so. Myself and my co-author, Professor Michael Hambrey, have been able to use almost exclusively our own photographs in this book and our earlier volume The Continent of Antarctica (2018). This is because, between us, we ’ ve had the great privilege of having visited many parts of the polar world. It was important to make sure that the Antarctic book was printed on high quality paper to do justice to the photographs.

I’ll also continue to teach an annual week-long course on Arctic marine geoscience at the University on Svalbard (UNIS) in the high Arctic. I’ ve taught the course almost every year for the past 25 years and will return this September, helping to train young scientists there as part of an international Masters Programme.

I’d like to stay fit and enjoy being a grandparent, too. Evelyn and I enjoy spending time at our cottage in Cornwall with the family when we ’ re not working. As you can tell, retirement from the Directorship of the Scott Polar Research Institute is a long way from giving up my polar interests! n

1 Julian has represented the UK on the councils of both the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and is also a past Chair of the UK

National Committee on Antarctic Research. He has received a number of awards for his scientific work including: the Polar Medal (1994) from HM The Queen for “ outstanding contributions to glacier geophysics ” ; the Founder ’ s Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society (2008); and the Lyell Medal from the Geological Society of London (2018). 2 Dowdeswell J.A., Batchelor C.L., Montelli S., Ottesen D., Christie F.D.W., Dowdeswell E.K. and

Evans J., 2020. Delicate seafloor landforms reveal past Antarctic ice-shelf retreat of kilometres per year.

Science, v. 368, p. 1020-1024. 3 Christi F.D.W., Benham T.J., Batchelor C.L., Rack W., Montelli A. and Dowdeswell J.A., 2022.

Antarctic ice-shelf advance driven by anomalous atmospheric and sea-ice circulation. Nature

Geoscience, v. 15, p. 356-362.