WILLIAM SCOTT RA

As a gallery dedicated to Modern British art, it is an honour to present an exhibition of one of our leading artists. I still remember the first William Scott painting I came across when new to the art world – his clarity of vision made an immediate impression. It is therefore a great excitement to collaborate on a project which celebrates Scott’s key contributions to twentiethcentury art.

‘William Scott CBE RA (1913-1989): Themes and Variations’, is an exhibition of oils and works on paper spanning three decades from the 1950s to the 1980s. Working closely with the William Scott Estate and chosen directly from the family’s collection, the paintings and works on paper in this exhibition reveal an artist who never ceased to refine, question and reinvent. From early explorations of still life to bold abstractions, Scott forged a language that was rooted in the European tradition but was also open to the transatlantic dialogues that shaped the art of the twentieth century. This innovative approach to painting firmly places Scott among the defining figures of post-war art.

Our collaboration with William’s sons, Robert and James Scott, Robert’s wife Lisa, and James and Jessica Rawlin, reflects not only long friendships dating back to 1990s auction days, but also a deep admiration and study of Scott’s work. Over many years, the Jenna Burlingham Gallery is proud to have helped collectors, both in the UK and internationally, with their acquisitions of William Scott paintings, works on paper and prints.

We hope this exhibition, the first solo show in the UK since 2017 and including some pieces offered for sale for the very first time, will resonate not only with our longstanding collectors, but also with a new generation of admirers, ensuring the continuation of Scott’s legacy.

Jenna Burlingham, 2025

Themes and Variations

When the title of this exhibition, Themes and Variations, was first suggested, it seemed immediately appropriate. Both words were ones William used, incorporating them into the titles of works which show the development of his ideas.

The paintings and drawings exhibited here cover almost four decades of our father’s career as an artist, from the early 1950s through to the mid-1980s, and those concepts of Theme and Variation can be found throughout. Certain forms return, sometimes transformed, many years after they first appear; others, such as the pan and bowl, remain constant, evolving gradually over time. Our father was a very modest man from humble roots and those kitchen implements connect back to his childhood in Northern Ireland.

Seeing the photographs of William in his studio reproduced in this catalogue reminds me of how his ideas evolved over time, from the smallest drawing to the largest painting, either the beginning of a new work or the continuation of the last. At all times he consciously considered the space between objects and their relationship with the edge of the canvas or paper.

My wife Lisa and I first met Jenna Burlingham about thirty years ago when she worked at Phillips auctioneers with James Rawlin, whose idea this exhibition was. As with many things in life, it was a network of connections that brought us into contact.

When William was Head of Painting at Corsham Court, formerly the Bath School of Art, from 1946 to 1956, it was an innovative place, with Peter Lanyon, Terry Frost and Howard Hodgkin

William Scott with Luca in front of ‘Untitled’, 1967. Photograph: © James Scott

all teaching there. The Head of Lithography was Henry Cliffe, Harry to his friends. Harry had previously been a student at Corsham, as well as knowing William during the war when Harry was his boss! On the occasion of Harry marrying Valerie in 1950, our father gave them a painting, ‘Still Life with Bowl and Olives’, as a wedding gift.

It was William’s habit that if he made a painting he particularly liked, for various reasons he might paint a second version. Thus, our ‘Still Life with Bowl and Olives’, in this exhibition, was made to keep at home.

This painting, which still looks very modern, was made over seventy years ago, but it still brings back memories not only of William’s gift to a wartime friend but also a wonderful party at Phillips. That was almost three decades ago at the reception for the auction when Harry’s sons sold their own version of ‘Still Life with Bowl and Olives’ and my wife Lisa, myself, Jenna, James and their colleagues enjoyed ourselves immensely!

Such connections between artists appear again in the iconic photograph of William and Mark Rothko, taken at our Somerset home, Hallatrow, by my brother James and about which he writes elsewhere in this catalogue. Mark and William had become close friends since meeting in New York in 1953 and they continued corresponding for many years, discussing their work.

I hope that you too will enjoy the opportunity to discuss our father’s work.

Robert Scott, 2025

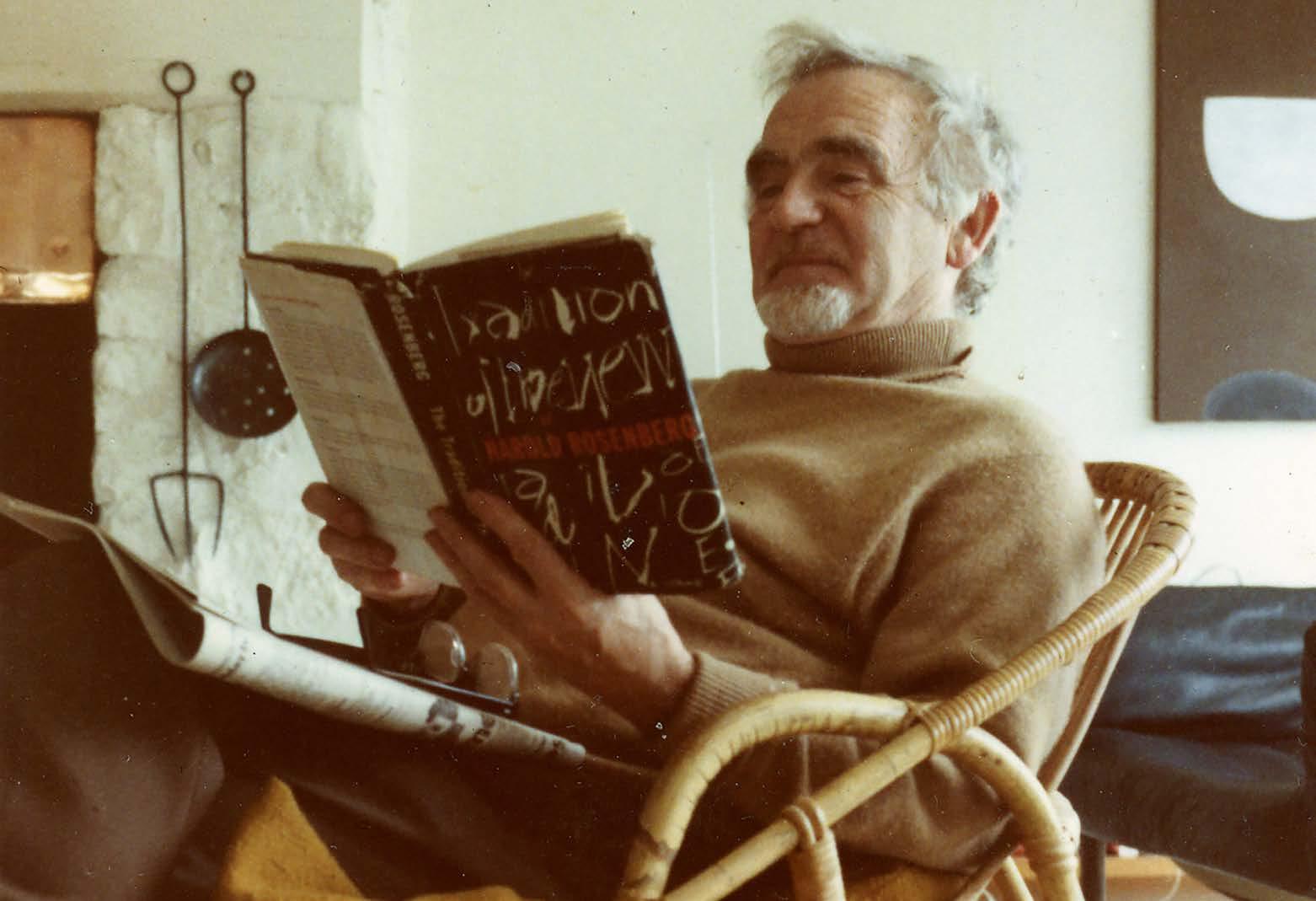

William Scott at Bennett’s Hill Farm. Photograph: © James Scott

On Photography

My father never had a camera when I was young. As far as I can remember, neither did my mother. But, as a child, my godfather gave me a simple box camera and this is where for myself, it all began. Suddenly the world became a different place. Now I had a tool enabling me to convert all that was around me into black-and-white images. I would leave the exposed rolls of film at Boots and a few days later pick them up. Between these moments, I would excitedly count the days until we could go in and collect the printed pictures. Packed in a wallet alongside the negatives, I would quickly rifle through the often blurred and indistinct images until I came to one that jumped out bringing back a face, a smile, a moment in time. Later these square black-and-white prints were neatly put into an album that survives to this day.

Friends and family, strangers and animals all became my subjects, but especially my father. I hung out in his studio, and snapped him and his friends at the pub. Then, when my father began to share this interest I helped him buy his first camera, a 35 mm Agfa Silette. I taught him the principles of exposure, f-stops and shutter speeds and focus. At his direction, I set up simple still lifes in the backyard with pots and pans on a plain white background. Then my father meticulously moved the objects around, adding a spoon or knife or fork until the arrangement pleased his eye. Ever more ambitious, WS upgraded from his Agfa Silette to a Leica III C and began to set up even more elaborate compositions.

I always felt that it was something about these early photos that started new directions in my father’s painting. While never copying directly from the pictures themselves, he now found a new freedom, abstracting even further through his use of colour, form, texture and composition. In his mind I believe these images of isolated kitchen objects were like missiles projected from another world; images that, launched anew, slowly released themselves, revealing their innate power and beauty.

After the still life arrangements, WS moved on to old stone walls. The North Somerset house, where we lived, surrounded by these walls, was the perfect background. My father had specific parts of them he liked to photograph, details which sometimes would uncannily reflect a Scott painting. In 1959, when Mark Rothko visited with his wife Mel and daughter Kate, WS posed with Rothko in front of one of these walls while I took the now much-reproduced photo of the two of them. They were great friends, and, he told my father in a letter, it was a photograph Rothko kept hanging in his house as a reminder of this happy family visit.

James Scott, August, 2025

William Scott and Mark Rothko at Hallatrow, 1959. Photograph: © James Scott

What matters to me in a picture is the ‘indefinable’1

A few years ago, I found myself in conversation with a young artist who had attended both the RCA and, like Scott, the Royal Academy Schools. They had recently turned their painting towards still life but had been having a great deal of difficulty ‘anchoring’ the objects they painted to the tabletop. I picked up a book of Scott’s paintings and found a few examples for them that seemed to follow the kind of imagery they were seeking and the stunned moments of appreciation and understanding of how another generation had tackled those same problems led me to thinking two things. The first was that clearly time had not diminished Scott’s ability to make images that did what he had hoped to achieve and could still speak to a contemporary audience. The second was that somehow those earlier voices had been allowed to drift a little out of the awareness of the artists of now. How different it had been…

In the third quarter of the twentieth century, British art had almost an embarrassment of riches. The elder generation who had worked between the world wars, such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, were still producing great work, their slightly younger contemporaries like Patrick Heron or Peter Lanyon were blossoming and those still at art school, Bridget Riley, David Hockney, Allen Jones et al, were about to step into the fray too.

William Scott was at the absolute centre of this. A student in the mid-1930s, service in the Second World War brought a slight interruption to his artistic career but in the late 1940s and onwards he built up a formidable reputation as one of the leading painters in Britain, a reputation that was celebrated both in Europe and the Americas. Collected internationally, he was one of the pre-eminent figures of the post-war art scene in London which was celebrated in that seminal document of its time, ‘Private View’, the lavishly produced and illustrated book put together by Bryan Robertson, John Russell and Lord Snowdon in 19652. He was honoured with a large career retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1972.

Scott’s painting career, which spanned almost six decades, saw his work develop in a variety of ways, but also stayed remarkably true to the basic tenets of his art. His subjects were largely still life and the figure,

Patrick Heron, William Scott, Peter Lanyon and Jack Smith at Tinner’s Arms, Zennor, Cornwall, 1958. Photograph: © James Scott

and within these he moved from representation to abstraction and back again. Yet one never mistakes a Scott for someone else’s work. Throughout this long life of painting and drawing, there is a constant search for the heart of his subject, what he referred to as ‘the things of life’3. Even at his most abstract, Scott remained devoted to the idea of how the forms he used related to each other, so be it a pan and a bowl, or a triangle and a curved line, there are always hints and reminders of the real world about us, the world which is revealed by looking.

This life-long quest to see and understand is one that artists comprehend but is a kind of mystery to everyone else. To animate a form, to use a colour to create space and distance in a painting: these are the alchemical components which all artists use. But only very few extract from their technique the additional magic that makes the difference, that creates the art. Scott was a master of transforming the everyday into something of wonder.

Writing in 1974 for an exhibition of Scott’s drawings in New York, the distinguished art historian and museum director Alan Bowness sought to pinpoint those elements which set Scott’s work apart from the rest of the field4. He identified a form of dualism in Scott’s work where things both are, and are not, as they seem. The drawings and works on paper typify this. The forms in these works often have a direct identity, such as a bowl or mug, but there is more to them than this. How they relate to other forms in the work is a pictorial choice but it frequently seems to suggest a relationship between the two, something that goes beyond the actual space on the support and hints at the implied movement and connections which animate Scott’s work.

In the artist’s earlier years, his drawings and paintings on paper were not often exhibited independently, being regarded by the artist as a more private form of expression than his paintings. Nor did he especially see them as directly preparatory for a particular painting, rather that they offered Scott a way to explore, to feel his way towards an end. Indeed, Scott would quote Leonardo’s dictum that ‘drawing was the art of correction’. Thus, whilst in his later years works on paper began to be a larger part of his exhibited output, there remain many that are almost entirely unknown. Frequently having connections to works we know

William Scott in his Studio, 1960s. Photograph © James Scott

well, the paintings displayed in public collections or in the galleries of the upper echelons of the art world, they still remain individual statements, fresh and bright, brought out now into the world long after their maker has departed.

Several such works are included in this exhibition. Carefully chosen from the Artist’s Estate Archive, many have either never previously been exhibited or have spent decades out of sight. Brought out and hung alongside some of Scott’s paintings that cover the same periods, we are now able to once more be surprised by an artist whose work many think they know well. As Bowness debated in his essay, whilst Scott could often produce paintings that were monochromatic in that they focussed on a single prime colour, his skill as a colourist elevated these works by adding yet another layer of impact.

In the works included in this exhibition, we can see some of those colours we have come to associate most with Scott; the rich cobalt blues, the pungent ochres and oranges which vibrate a little on the retina, the deep terracottas and chocolate browns that change constantly with the ambient light of the room in which they are hung. Other less familiar tones are here too, catching our eye; acid yellows, fuschia pinks, warming greys.

These combinations of colour and form enliven the spaces they inhabit, offering us simplicity and complexity side by side, our very own touch of the ‘indefinable’.

James Rawlin, 2025

1 William Scott, ‘Artist’s Statement’ in Nine Abstract Artists, Alec Tiranti Ltd, London 1954, p.37

2 Bryan Robertson, John Russell, Lord Snowdon, Private View: The Lively World of British Art, Thomas Nelson & Sons, London 1965

3 Op.cit., p.37

4 Alan Bowness, Foreword, published in Lou Klepac (ed.), William Scott: Drawings, David Anderson, New York 1975, unpaginated.

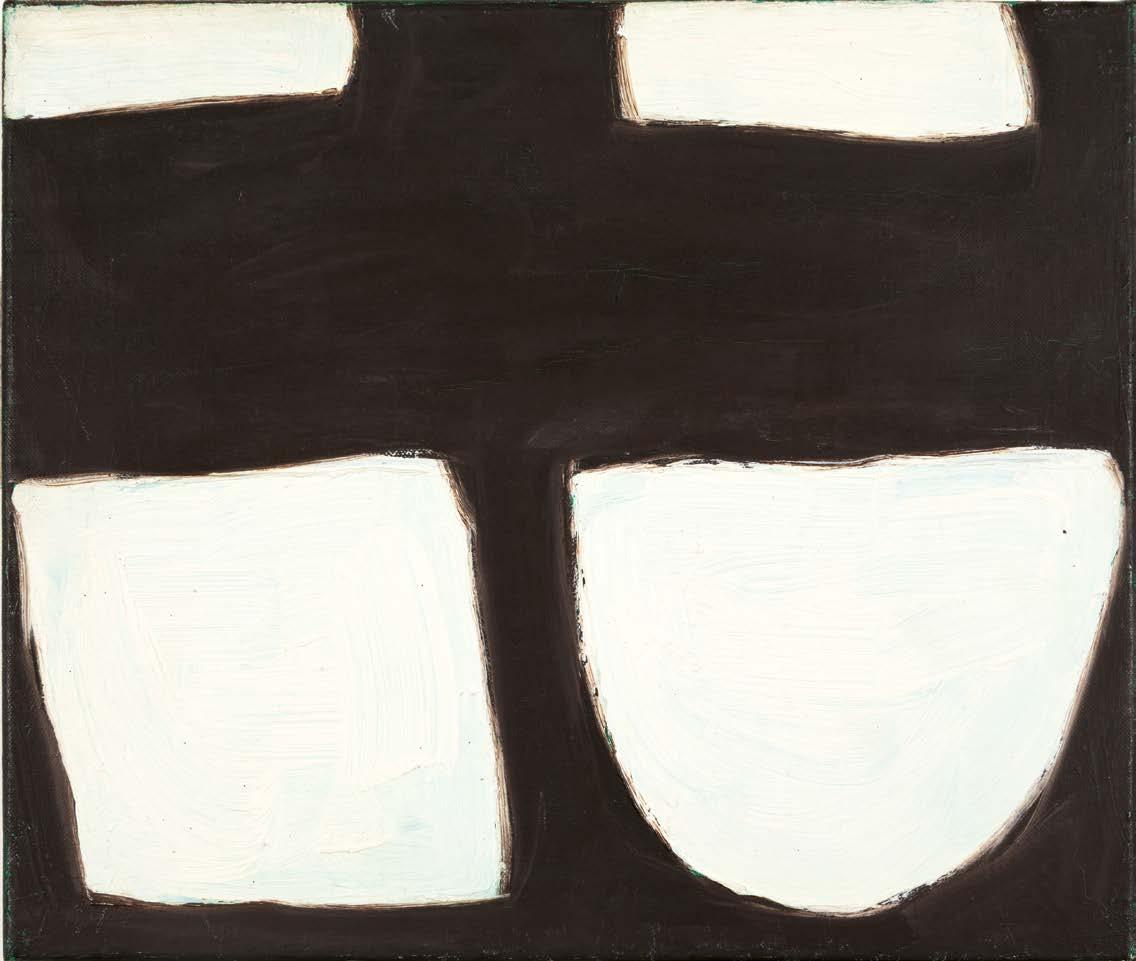

Still Life with Bowl and Olives, 1950 oil on canvas

55.5 × 64 cm / 21⅞ × 25¼ in

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1913-1951’, Volume 1, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.182, illustrated in colour

Untitled, 1957 signed and dated gouache

56 × 76 cm / 22 × 30 in

Exhibitions

Osaka, Kasahara Gallery, William Scott, 16 January – 7 February 1976, cat. no.12

Osaka, Kasahara Gallery, William Scott, 17 May – 29 May 1976, cat. no.2

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1952-1959’, Volume 2, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, p.123, illustrated in colour

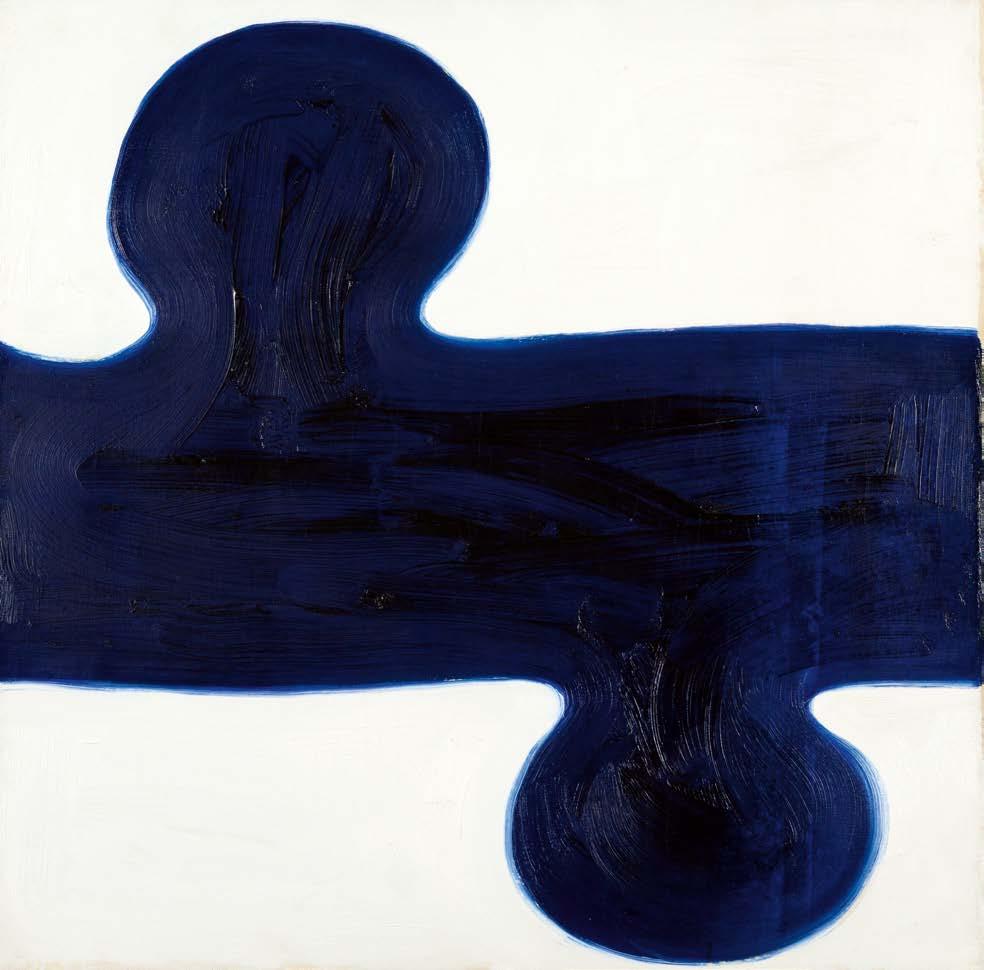

Blue and Black Painting, 1959

signed oil on canvas

101 × 126.2 cm / 39¾ × 49¾ in

Exhibitions

Zurich, Galerie Charles Lienhard, ‘William Scott’, 11 November - 12 December 1959, cat. no.14 (as ‘Painting’)

Tirol, Europaisches Forum Alpach, and touring, ‘Das Junge England’, 19 AugustDecember 1960, cat. no.36, illustrated in black-and-white (as ‘Blue Painting’)

London, Hanover Gallery, ‘William Scott’, 17 May - 17 June 1961, cat. no.21, illustrated in black-and-white (as ‘Blue Painting’)

British Council, touring exhibition to Cyprus, Lebanon, Iran and Iraq, as ‘Contemporary British Art’, 1962(?), cat. no.13

Bern, Kunsthalle, ‘Victor Pasmore, William Scott’, 12 July - 18 August 1963, cat. no.25 (as ‘Blue Black Painting’)

Belfast, Ulster Museum, ‘William Scott’, 12 September - 5 October 1963, cat. no.28 (as ‘Blue Black Painting’)

New, York, Anita Rogers Gallery, ‘Mark Rothko and William Scott: Continuing the Dialogue’, 26 April -3 June 2023, unnumbered catalogue, illustrated in colour, p.56

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1952-1959’, Volume 2, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.406, illustrated in colour

Alexander Auer (foreword), ‘Das Junge England’, exh. cat., Europaisches Forum Alpach, Tirol, 1960, p.11, illustrated in black-and-white (as ‘Blue Painting’)

Alan Gouk, “Patrick Heron II”, ‘Artscribe’, no.35, June 1982, p.33, illustrated in black-and-white (upside down)

(Abstract Painting), 1959 oil on canvas

40.8 × 45.7 cm / 16 × 18 in

Exhibitions

London, Osborne Samuel, ‘William Scott and Friends, An Exhibition’, 12 June - 13 July 2013, unnumbered catalogue, illustrated in colour pp.24-5

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1952-1959’, Volume 2, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.394, illustrated in colour

5

Ochre Collage, circa 1960

oil and collage on thick paper

21.3 × 29.4 cm / 8⅜ × 11⅝ in

6

Blue and White Collage, 1959 signed

gouache and collage

21.6 × 31.2 cm / 8½ × 12¼ in

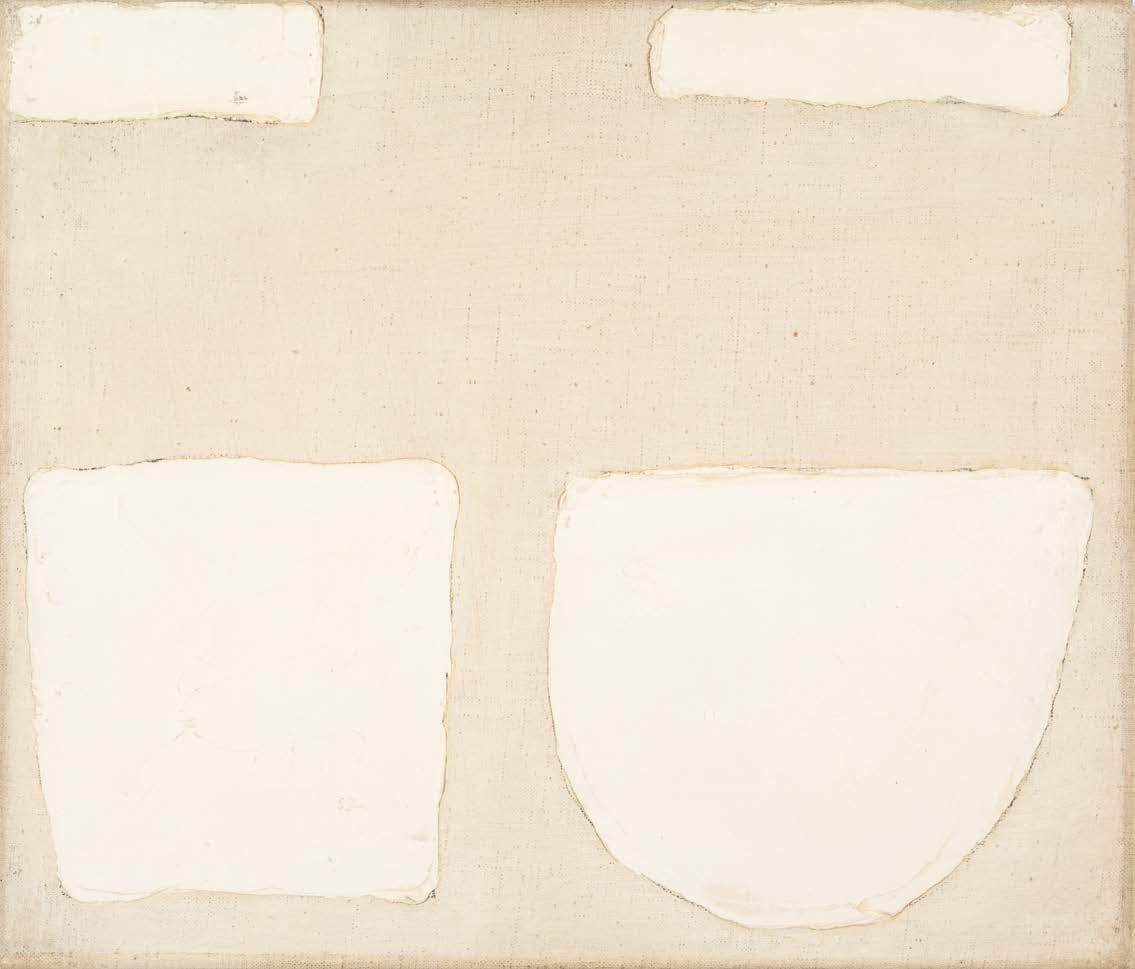

Whites, 1960

signed and dated verso oil on canvas

30.5 × 35.4 cm / 12 × 14 in

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1960-1968’, Volume 3, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.462, illustrated in colour

30.8 × 35.7 cm / 12⅛ × 14 in

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1960-1968’, Volume 3, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.543, illustrated in colour

Untitled, 1963 oil on canvas

56 × 76 cm / 22 × 30 in

Orange and Grey, circa 1962

gouache

Untitled (White Painting), 1961 oil on canvas

87 × 112.2 cm / 34¼ × 44⅛ in

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1960-1968’, Volume 3, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.484, illustrated in colour

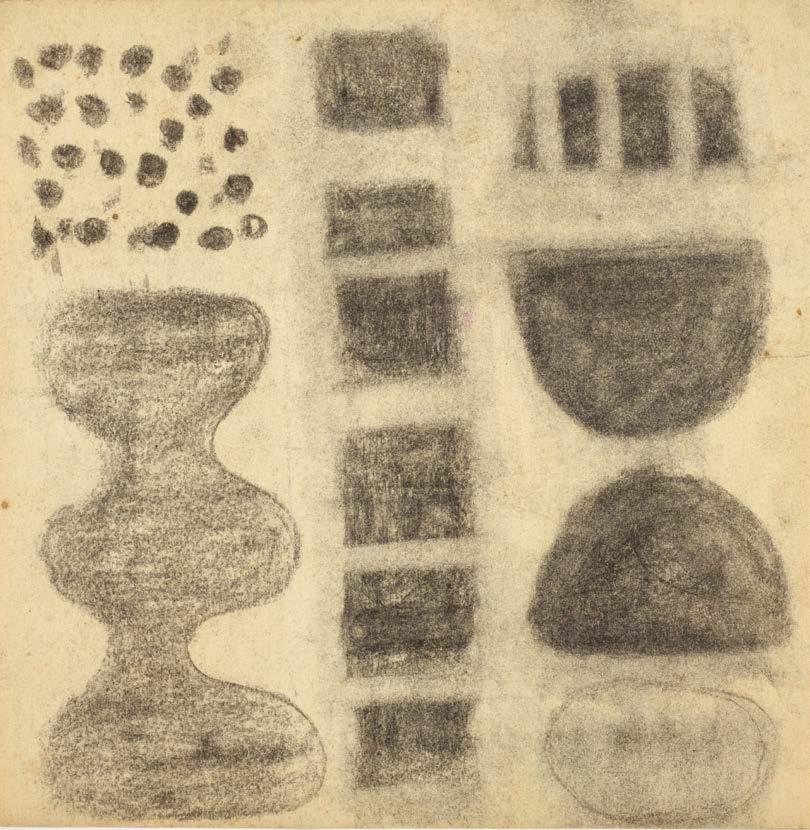

Berlin Blues Study, circa 1965

22.5 × 22.5 cm / 8⅞ × 8⅞ in

Gouache Blue and Black, circa 1962/63

28.3 × 39.6 cm / 11⅛ × 15⅝in

charcoal

12

gouache

1965

50.4 × 51 cm / 19⅞ × 20⅛ in

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1960-1968’, Volume 3, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.594, illustrated in colour

Untitled,

oil on canvas

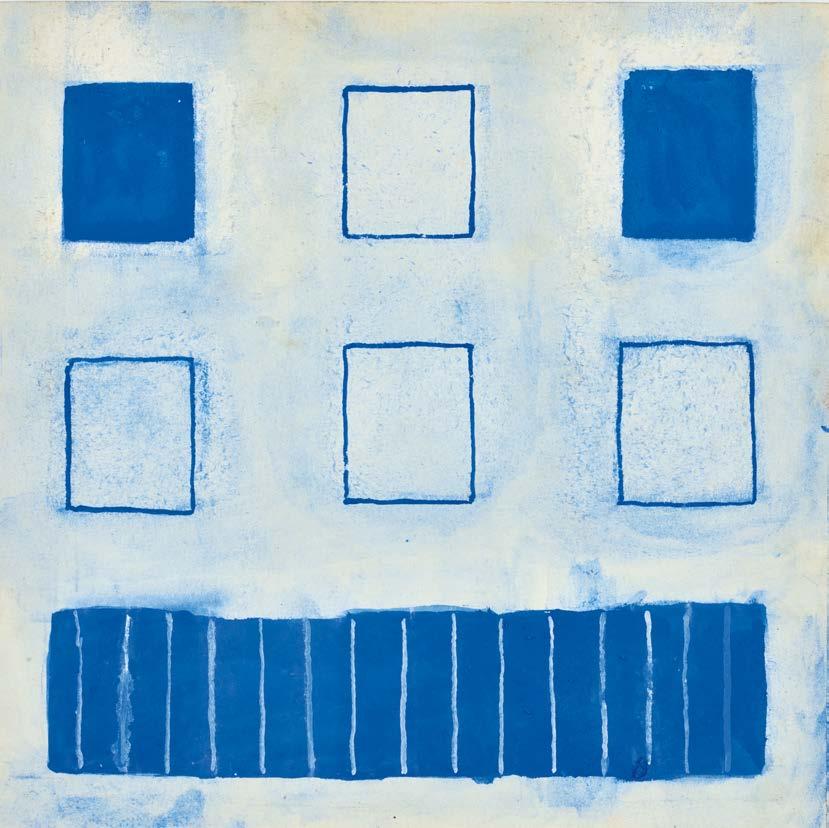

Blue and White, circa 1965

gouache

28 × 30.3 cm / 11 × 11⅞ in

Red with Wrath, circa 1965

gouache and collage

25 × 30 cm / 9⅞ × 11¾ in

15

16

Divided Blues, circa 1965

gouache

28 × 28 cm / 11 × 11 in

17

Darker Blues, circa 1965

gouache

28 × 30.2 cm / 11 × 11⅞ in

Original Gouache for Odeon Suite II, 1966 gouache

55.5 × 76.3 cm / 21⅞ × 30 in

The Odeon Suite consists of six lithographs, published by Editions Alecto, London and printed in Zurich by Mathieu AG

Still Life, Beans, 1976 signed and dated verso oil on canvas

63.3 × 75.6 cm / 24⅞ × 29¾ in

Exhibitions

Dublin, Dawson Gallery, ‘William Scott Twelve Recent Paintings’, 9 - 23 July 1977, cat. no.2

Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1969-1989’, Volume 4, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.801, illustrated in colour

Blue, Black and White, 1972 signed and dated gouache

57.5 × 78.5 cm / 22⅝ × 30⅞ in

Exhibitions

Perth, Australia, Lister Art Gallery, ‘William Scott 15 Gouaches’, 1973

Still Life Yellow Base, circa 1975 signed and dated gouache and crayon

56 × 76 cm / 22 × 30 in

Exhibitions

New York, Gimpel & Weitzenhoffer, William Scott, 26 April – 28 May 1983

Strong Note Orange, 1972 signed and dated verso oil on canvas

128.1 × 102.1 cm / 50⅜ × 40¼ in

Exhibitions

New York, Martha Jackson Gallery, ‘William Scott’, 3 January - 10 February 1973

Toronto, Gallery Moos, ‘An Exhibition of New Paintings by William Scott’, 13 October - 1 November 1973, cat. no.9

Lincoln, DeCordova Museum, ‘The British are Coming’, 1975

London, Gimpel Fils, ‘William Scott. Every Picture Tells a Story’, 26 February - 30 March 1985, cat. no.17

New York, McCaffrey Fine Art, ‘William Scott’, 27 February - 7 April 2010

London, McCaffrey Fine Art at Frieze Masters, ‘William Scott’, 11 - 14 October 2012

Hepworth Wakefield, and touring, ‘William Scott’, 25 May - 29 September 2013

London, Beaux Arts Gallery, ‘Four Giants of British Modernism: Terry Frost, William Scott, Peter Lanyon, Patrick Heron’, 19 September - 19 October 2019

Literature

Norbert Lynton, ‘William Scott’, Thames and Hudson, London, 2004, p.365, illustrated in colour

David Anfam, ‘William Scott’, McCaffrey Fine Art, New York, 2010, cat. no.33, illustrated in colour

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings 1969-1989’, Volume 4, London, Thames and Hudson, 2013, cat. no.729, illustrated in colour

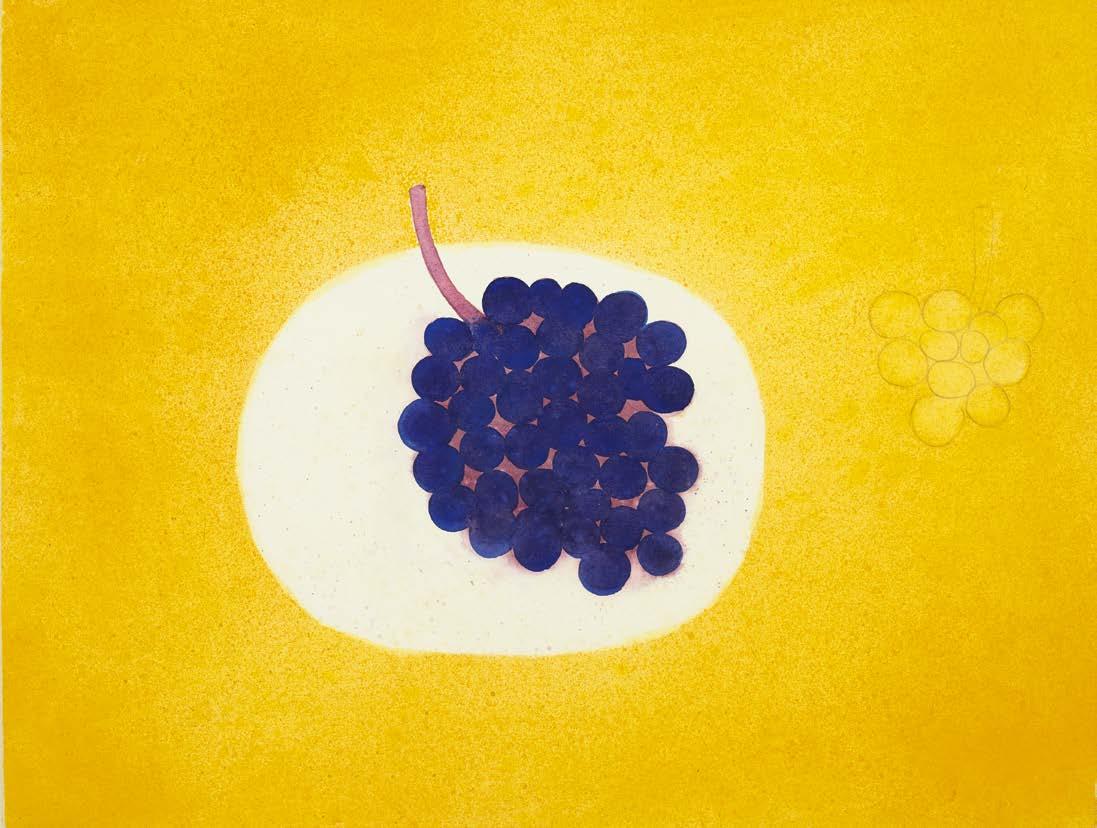

Original Gouache for Grapes, 1979

gouache and pencil

50 × 65 cm / 19¾ × 25⅝ in

The lithograph after this work was published in 1979 by Christies’ Contemporary Art and printed by Curwen Press

28 × 38 cm / 11 × 15 in

24

Poem for a Jug, circa 1980 pencil and pastel

28 × 38 cm / 11 × 15 in

25 Pan and Bowl, 1980 pastel, charcoal and pencil

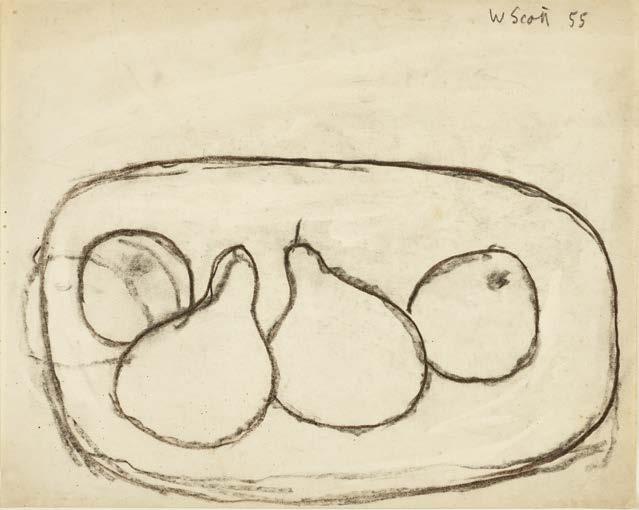

Untitled (Pears), 1955 signed and dated pencil

20.2 × 25.4 cm / 8 × 10 in Literature

Sarah Whitfield, ‘William Scott

Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings

1952-1959’, Volume 2, Thames and Hudson, London, 2013, illustrated p.131 27

Four Pears on a Plate, 1975 signed and dated charcoal and pencil

29.5 × 39 cm / 11⅝ × 15⅜ in 28

Grapes and Lemons, 1985 signed and dated gouache, pastel and charcoal

35.3 × 57 cm / 13⅞ × 22½ in

29

Pan and Spoon, circa 1980/82 pencil and gouache

27.5 × 28 cm / 10⅞ × 11 in

30

Bowl and Basket, circa 1976 pencil

27.5 × 39 cm / 10⅞ × 15⅜ in

Biography

1913 Born in Greenock, Scotland

1924 Moved to father’s hometown: Enniskillen, Northern Ireland where Scott began art lessons with Kathleen Bridle

1928–31 Studied at Belfast School of Art

1931–35 Attended the Royal Academy Schools, London and transferred from Sculpture to Painting in 1934

1937 Married sculptor Mary Lucas

1938 Settled in Pont-Aven, Brittany, co-founded an art school there with Geoffery Nelson Exhibited in the British Section of the Paris Salon d’Automne

1941–56 Taught at Bath Academy of Art, Corsham Court

1942 First solo show at Leger Gallery, London

1942–46 Served with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and then as a lithographic draughtsman with the Royal Engineers

1948 Solo show at Leicester Galleries, London and again in 1951

Met Patrick Heron in St Ives, Cornwall who became a lifelong friend

1951 Exhibited in ‘Sixty Paintings for ’51,’ organised by the Arts Council for the Festival of Britain

1953 First of several solo shows at The Hanover Gallery, London

Visited America and made friends with New York artists including Mark Rothko

1954 First of several solo shows at Martha Jackson Gallery, New York

1958 Represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale alongside Kenneth Armitage and Stanley William Hayter

1959 Rothko and his family stayed with the Scotts in Somerset during their tour of Europe

1960s Retrospectives in Zurich, Hannover, Berne and Belfast and included in major shows in London, Tokyo, Paris, Brussels, Copenhagen, Oslo and Rotterdam

1961 Awarded the Acquisition Prize at the São Paulo Biennale

1966 Appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

1972 Major retrospective at Tate Gallery, London curated by Alan Bowness

1977 Elected Associate of the Royal Academy; later elected Royal Academician in 1984

1985–86 Won the Korn/Ferry Prize at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition two years running

1986 Major retrospective at the Ulster Museum, Belfast, touring to the Guiness Hop Store, Dublin, and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

1989 Died in Somerset, England and buried in Enniskillen

1990 Memorial exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

1998 Major retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

2013 Centenary retrospective held at Tate St Ives, touring to The Hepworth, Wakefield and Ulster Museum, Belfast

Public Collections*

United Kingdom

British Museum, London

Imperial War Museum, London

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Royal Academy of Arts, London

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

National Museums Northern Ireland, Belfast

Tate, London

V&A, London

Europe

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Genoa

U.S.A.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

MoMA, New York, NY

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

*For a full list of exhibitions and public collections visit williamscott.org

Jenna Burlingham Gallery was established in Kingsclere on the Hampshire/Berkshire border fifteen years ago. It has since become a destination for buyers and sellers of Modern British and Contemporary paintings, prints, sculpture and ceramics.

In 2021 we moved to Rope Yard, a former rope merchant’s home and workshops, where we exhibit our extensive inventory in furnished interiors. This inventory ranges from entry level to museum quality works and our team is always on hand to give straightforward guidance to private and corporate collectors, galleries and institutions, art advisers and interior decorators.

All our works can be seen on the website or in the gallery, with on site viewings by arrangement throughout the UK with our weekly van service.

We also regularly exhibit at the London art fairs including the Decorative Fair in Battersea, the London Art Fair in Islington and the British Art Fair in Chelsea.

Jenna Burlingham Gallery

In association with the William Scott Estate and J&J Rawlin

Works © William Scott Estate 2025

Archive photographs courtesy of William Scott Estate

Published by Jenna Burlingham Gallery 2025

Catalogue © Jenna Burlingham Gallery

Gallery interior photography by Boz Gagovski © William Scott Estate 2025

Design by Graham Rees Design

Inside front and back cover photographs by William Scott, Studio Still Life Arrangement