6 minute read

The Next

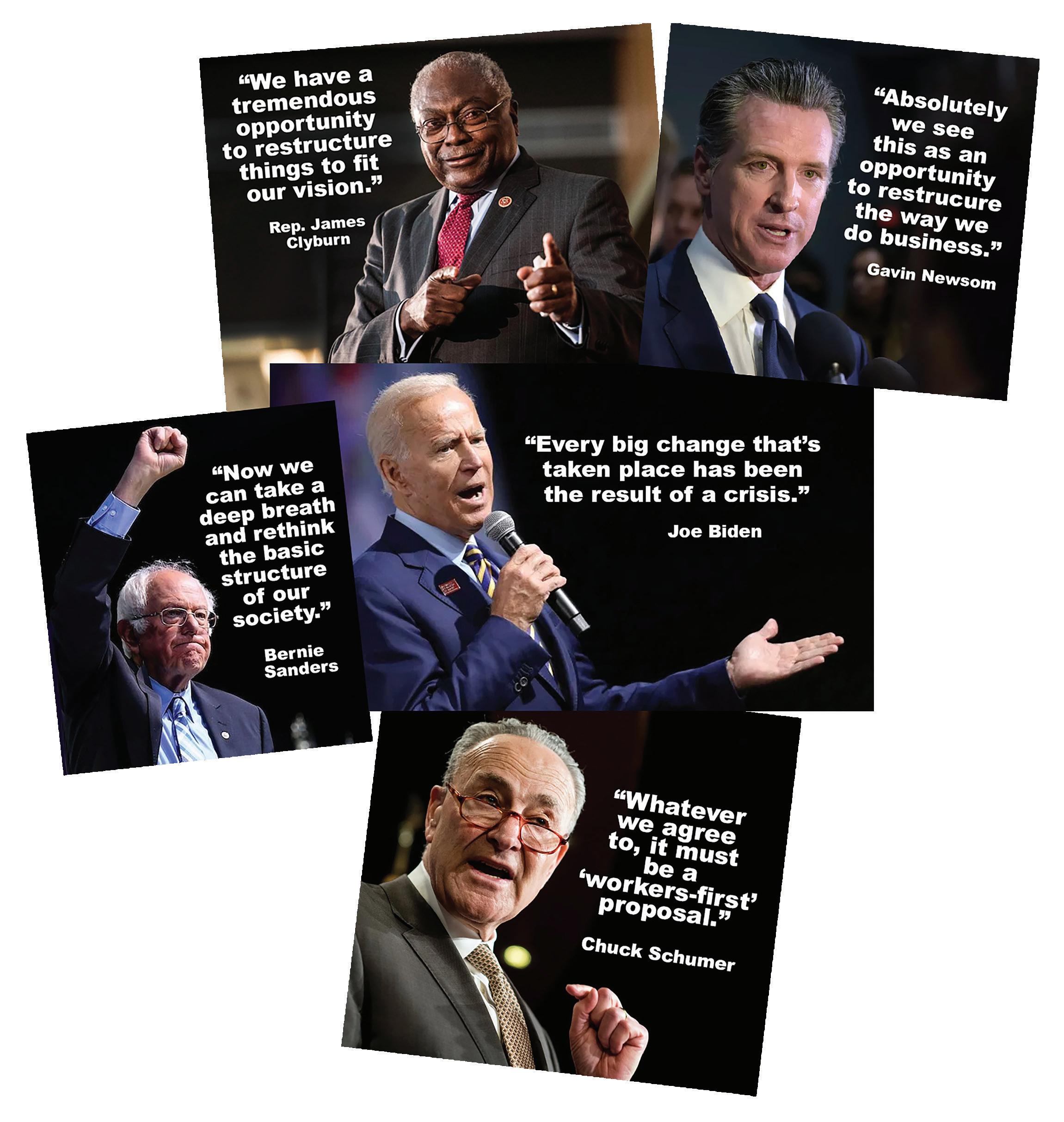

If public-sector unions thought Janus was devastating,wait'll they get a load of a follow-up lawsuit many believe has the potential to change the whole dynamic between workers and government unions.

By JAMES ABERNATHY

Advertisement

Litigation Counsel

The question of whether government employees could be forced to join — and financially support the political activities of — a labor union has been hotly contested almost from the moment cities and states first began permitting collective bargaining in the late 1950s.

Since then, the issue has been shaped by numerous court decisions, most recently Janus v. AFSCME in 2018, which the unions and their backers — all their denials notwithstanding — recognize was a body blow to the legalized protection racket they’ve been operating for decades. But the war isn’t over. In fact, a case currently working its way through the court system, Belgau v. Inslee, has the potential to be the next in a long line of important precedents.

It promises to change the entire dynamic between unions and government

workers by actually applying the language of Janus and the clear intentions of its authors.

First, though, let’s review how we got here.

In 1977 the United States Supreme Court issued a decision the justices believed would settle the matter: States and unions could force public employees to subsidize collective bargaining but not unions’ political speech.

For more than 40 years, this decision — Abood v. Detroit Board of Education — wreaked havoc in publicsector employment. Unions, however, were no strangers to political gamesmanship and immediately went to work devising ways to exploit publicsector workers by cashing in on the political power of the politicians they were able to buy or bully.

Through compelled union dues, public workers were forced to fund their own intimidation and exploitation.

For the four decades following Abood, public employees’ rights were extremely limited and very few ever even learned of them. Moreover, workers who learned of their rights faced complicated, union-dominated procedures when they attempted to exercise them.

Simply put, since Abood, unions have perfected systemic intimidation, and courts let them get away with it — unfortunately holding all of the aforementioned practices constitutional.

It wasn’t until the 2010s that the Supreme Court finally signaled a willingness to seriously push back against what the justices eventually came to call the “abuses” heaped upon public employees by union executives more interested in filling their pockets than protecting employees’ First Amendment rights and public employers who shrank in the face of union intimidation and political power.

In 2012, the Supreme Court issued Knox v. SEIU, Local 1000, in which it held unconstitutional the union practice of imposing special political assessments against nonmember employees who had already objected to union membership and the payment of full union dues. The court stated boldly that:

“Because a public-sector union takes many positions during collective bargaining that have powerful political and civic consequences, the compulsory fees constituted a form of compelled speech and association that imposes a significant impingement on First Amendment rights. Our cases to date have tolerated this impingement, and we do not revisit today whether the Court’s former cases have given adequate recognition to the critical First Amendment rights at stake.”

The ruling also referred to the court’s previous acceptance of compelled union fees as “an anomaly” in First Amendment jurisprudence. Encouragingly, the court also questioned opt-out schemes, calling them “a remarkable boon for unions,” even though normally courts “do not presume acquiescence in the loss of fundamental rights.”

These statements signaled to many the justices might be willing to revisit Abood and the question of whether compelled union fees were indeed constitutional.

Two years later, the Supreme Court issued Harris v. Quinn, in which it declined to extend Abood’s tolerance of compelled union fees to partial-public employees such as home healthcare providers who are, in reality, employed by the client receiving the assistance and only subsidized by Medicaid.

The Harris ruling again referred to Abood as “an anomaly,” and called Abood’s reasoning “questionable on several grounds.” The court concluded Abood could not be extended to partial-public employees because it is a “bedrock principle that, except perhaps in the rarest of circumstances, no person in this country may be compelled to subsidize speech by a third party that he or she does not wish to support.”

The days of compelled union fees were coming to an end, and unions could read the writing on the wall. Finally, in 2018, the Supreme Court delivered the kill shot to compelled union fees in Janus v. AFSCME.

The landmark ruling concluded that, “Abood was wrongly decided and is now overruled.”

“Abood’s proponents,” it read, “have abandoned its reasoning, the precedent has proved unworkable, (and) it conflicts with other First Amendment decisions.”

The ruling further affirmed what had been obvious to most for decades — that Abood has led to “practical problems and abuse.”

Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito noted that, “(N)either an agency fee nor any other payment to the union may be deducted from a nonmember’s wages, nor may any other attempt be made to collect such payment, unless the employee affirmatively consents to pay.”

Contrary to the unions’ subsequent arguments, however, Janus did much more than simply prohibit compelled union fees. It also required affirmative consent to the payment of union dues before union dues could be exacted from employees.

“(B)y agreeing to pay (dues), nonmembers are waiving their First Amendment rights, and such a waiver cannot be presumed,” Alito wrote. “Rather, to be effective, the waiver must be freely given and shown by clear and compelling evidence.”

At a minimum, the wording should put an end to “opt-out schemes” that resulted in the payment of so-called “agency fees” to the union without the workers’ consent.

But applied correctly, Janus should go much farther.

By affirming that the payment of union dues requires an informed and affirmative waiver of First Amendment rights, the ruling obligates unions and employers to obtain clear and compelling evidence that employees know of — and have voluntarily waived — their right to pay nothing to their union.

Unsurprisingly, unions emphatically deny that interpretation of the ruling, while simultaneously scheming to circumvent it.

For example, even before the ruling was issued, unions created new membership cards that included irrevocability provisions that trap employees into paying union dues for a year at a time and limit employees’ ability to object to union membership and dues payments to only a narrow 10-day to two-week annual escape period.

Unions have for decades used compelled fees as leverage to bully employees into become full, dues-paying union members rather than paying reduced agency fees by depriving nonmembers of the ability to vote on the employment contract the union

would negotiate and would be forced on union members and nonmembers alike. (Amazingly, courts permitted this union practice.)

Moreover, employers and unions continue to enforce maintenance of membership agreements, which also trap employees into paying union dues for long periods of time even after they learn of their rights for the first time and opt out.

Old habits die hard, and the unions — having spent 40 years pushing the envelope under Abood — clearly in

Signs of Freedom

tend to do the same under Janus.

That’s where Belgau v. Inslee comes in.

The case involves seven Washington state employees who are challenging deduction of union dues from their wages by a state employer over their objections.

These employees, represented by Freedom Foundation attorneys, signed union membership and dues deduction authorization cards in the months leading up to Janus. Union leaders did not, however, notify these employees of their rights and offered them nothing in exchange for agreeing to the irrevocability provisions in the cards.

Obviously, these cards do not constitute clear and compelling evidence the employees knowingly, voluntarily and intelligently waived their First Amendment right to pay nothing to a union. (The case is currently pending in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. It has been fully briefed and argued, and a decision is expected soon.)