10 minute read

Who's to Say?

Nowadays, we've come to accept the public has an interest in funding basic education. The more relevant questions, however, are what exactly do we mean by 'public interest,' and what type of education best serves it?

ollege Board, a not-for-profit organization that advocates for college enrollment and administers the SAT, appeared to validate what your parents always told you about the path to success when it wrote just a year ago that, “In 2018, the median earnings

Advertisement

By JAMI LUND Senior Policy Analyst C

of bachelor’s degree recipients with no advanced degree working full time were $24,900 higher than those of high school graduates.”

If the the logic of this was flawless and immutable for all college attendees, nobody eligible would miss the opportunity to attend. But among the bits of evidence the College Board assembled are some troubling facts. In 2018, for example, a quarter of those with a college degree earned less than $45,000 annually.

Among recent college graduates, 43 percent were “underemployed” in 2017 meaning the degree was not required for the position they held.

The median earnings of those with only a high school diploma were $40,500 in 2018, which is not far from the earnings of those with “arts and letters” degrees like psychology, education, sociology, English, biology, history and philosophy.

These are the results for those who actually obtain a degree. The National Center for Education Statistics reports that 38 percent of students who begin seeking a bachelor’s degree have not obtained it after six years. These have likely dropped out, although some may have transferred.

The tuition price for a four-year degree can range from $85,000 to $200,000 —if the student finishes within four years. More than half , however, don’t, which means additional terms and tuition to complete.

Public colleges’ tuition costs about a third of the tuition for private schools student, but the overall cost of public institutions is comparable with government funding the difference.

In 2017-18, state and local funding for public higher education averaged $7,850 per student per year. Some of these funds are appropriations directly for public colleges and some are for need-based student grants to cover tuition.

State and local governments provided $85.8 billion to public institutions of higher education in 2017-18. Federal grants and tax benefits provide billions more.

At public four-year institutions, 16 percent of revenue is from federal, state and local student grants, 41 percent of revenue is from state and local appropriations, and the remaining 43 percent from student tuition.

Additional public subsidy comes in the form of federal tax credits. Student tuition in most cases provides an additional tax credit, American Opportunity Credit (AOC) and the Lifetime Learning Credit (LLC).

The AOC is a one-time full tax credit of $2,500 for most tax filers who are paying tuition. It is even partially refundable if the taxpayer paid no taxes. The LLC is an ongoing $2,000 annual deduction for higher education expenses.

In 2016, students pursuing higher education received about

$91 billion in financial support from federal spending programs and tax expenditures.

Additional programs stimulated by federal provisions are student loan programs.

As of December 2018, outstanding student loans issued or guaranteed by the federal government totaled $1.4 trillion and a portion of these are eventually forgiven.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that of the loans disbursed from 2020 to 2029 undergraduate borrowers would have $40.3 billion forgiven and graduate borrowers would have $167.1 billion forgiven.

IS HIGHER EDUCATION A REQUIREMENT FOR LIFE?

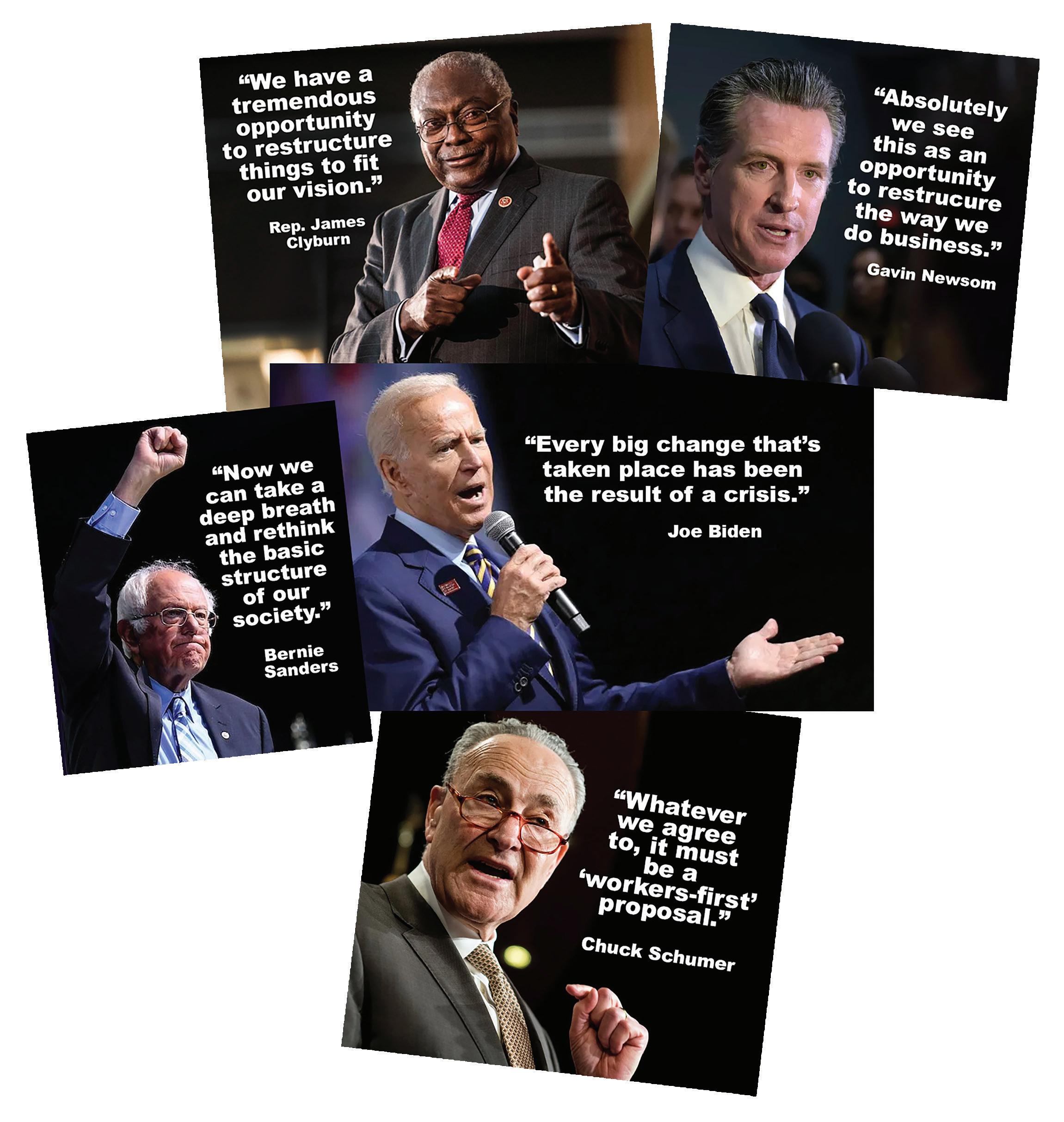

Rhetoric from the Left has recently suggested that the tremendous current investment in college education for the benefit of a portion of the citizenry is not enough, and that college education should be free for all.

Nearly every Democratic candidate for president embraced free two-year colleges, and a few campaigned on free public bachelor’s degrees and college debt elimination.

The irony of taxing the majority of Americans who are employed without a bachelor’s degree to subsidize others who will surpass them in income seems to be lost on the progressive Left.

Such a massive transfer of wealth from the low earners to high earners surely must have some justification unless it is merely pandering to middle-class voters.

It is true that a growing percentage of posted jobs require a degree, and this trend is not expected to change.

Currently 24 percent of the workforce has a bachelor’s degree, and another 15 percent has more than a bachelor’s degree, leaving two-thirds of the current workforce employed without a bachelor’s degree.

Some suggest the growing requirement of a degree is a proxy for a general decline in work ethic and skills.

When applicants for positions are plentiful, requiring a college degree at least weeds out those who have not been able to show the skill set needed to spend four years on an endeavor satisfying requirements set by others.

This idea, called “degree inflation”

by the Harvard Business School researchers, suggests employers need to know that candidates for middle-skills jobs have a grasp of technologies, and written and verbal communications.

Employers defaulted to using college degrees as a proxy for a candidate’s skills.

The report on degree inflation points out the practice hurts the average American’s ability to enter and stay in the workforce, causes employers to pay more without getting any material improvement in productivity and makes many middleskills jobs harder to fill.

Meanwhile, trades and skillsbased employment are key areas of employment growth that don’t require a degree, and yet are not receiving this level of public subsidy.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics faster-than-average growth in the construction industry in this decade, and the median annual wage of $45,820 in 2017 exceeds the $37,690 median wage for all industries.

So what is the public interest in taxing all for the exceptional earning potential of others?

THE POSSIBLE PUBLIC INTERESTS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

If there were justification for a large and potentially increasing investment in higher education, what would it be? The advocates for higher education make these claims. n “Breaking the cycle of poverty”

The public has an arguable interest in aiding those raised in poverty to reach a level of self-sufficiency. Many of the discussions about the benefits of higher education boil down to this point.

The public already invests in public assistance, but could save those costs by investing in higher education. n “High-demand jobs” supply

needed high-skill, public interest professionals

The anecdotal example of this interest is the need for nurses. Data and want advertisements demonstrate that some services are limited or exceptionally costly because of shortages.

The public has an interest in encouraging a ready supply of some services. Defining which services are of “public” interest and which

are of individual or corporate interest is obviously tricky but attempting to do so would help prioritize strategies for serving the public. n “Middle-class access” means

good jobs for political constituents’ children

This is an often unstated interest hidden in statistics about imported professionals. The implication is that merely having professionals is not enough, even if these have their education subsidized elsewhere. The state has an interest in making sure the next generation of Washingtonians can compete for these jobs with equivalent public subsidy. n “Higher education infrastruc

ture,” creates the capacity to provide higher education services

The public has an interest in owning, operating and controlling institutions of higher education to be certain the infrastructure is available to supply the previously mentioned public goods.

In addition to controlling the means to produce graduates, the means to supply public-interest research services is likewise in the public interest.

However, one could easily argue that, as with other industries, a narrower interest in capacity and availability could be met by stimulating the growth and spread of private sector providers.

POSSIBLE SPECIAL INTERESTS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

The public institutions of higher education have an interest in the growth of their funding, programs, wages and scope.

While public interest is mentioned prominently in their mission statement, the more pressing demand of college administrators is to make payroll, demonstrate progress to trustees and to grow the operation.

Likewise, a cottage industry has grown up around higher education, meaning student loan enterprises, testing organizations and research enterprises also share an interest in the spending on higher education for reasons unrelated to the public interest.

Studies have shown that expanding the availability of public funds, whether by student grants or loans or direct appropriation, has increased the cost of higher education faster than the rate of inflation.

The economic principles of “free” money being easier to spend would suggest this outcome. A higher education institution, whether public or private, cares more about enrollment and tuition than a trillion dollars in federally backed student debt or even student completion rates.

This is because the bills get paid a year at a time.

Another possible special interest is the businesses that benefit from public subsidy of the training of their workforce or their sector of the economy.

Many employers would love subsidy of the training of employees, and much of the policy seeking targeted subsidies of high-demand jobs are pushed by employers who would otherwise bear the training costs.

Even if workforce training is a public interest, the options for encouraging economic activity are perhaps better addressed in tax policy or economic development policy.

Finally, the students and their families have an interest in their own financial success. To use the government to subsidize the tools of a student’s extraordinary earning potential is not automatically a public interest. When someone starts an auto repair shop, we don’t expect government to buy their building and tools for them.

Instead, the public charges them for permits, impact fees and several layers of taxes that others don’t pay. So why would giving tens of thousands of dollars to provide a middle-class family’s son a law degree be different?

When considering politicians’ rhetoric, testimony in Congress, articles in publications and even young protesters’ signs calling for student debt forgiveness, consider whether the interest prompting the voice is truly a public interest or a private interest.

Using government’s power to fund a narrow financial interest is the very definition of crony capitalism.

EVALUATING HIGHER EDUCATION

Thinking about the public interest allows one to leave aside the institutions’ interest in budgets, compensation, program additions and employees. The “cost” of meeting the public interest is important, but is not necessarily tied to institutional accounting.

If we have correctly identified the public interest, then achieving this interest efficiently could be considered.

For example, the optimal program for meeting the public interest would be offering large scholarships for nursing training to poor students, completing on time and getting placed in the profession.

Unfortunately, our methods of public subsidy for higher education do not demonstrate these priorities. It is true that most grant and tuition subsidies are needs based, although often with a surprisingly high-income threshold considered “need.”

These programs don’t usually concern themselves with whether students complete their programs or whether the programs students select produce earnings greater than lower levels of education.

Efficiency, relative costs and measures of success also become easier to identify once the “point” of the expenditure is established. For example, keeping track of job placement and wage improvement would be essential to truly know if “breaking the cycle of poverty” was working.

Stimulating interest in “high demand jobs” in shortfall areas can be measured but does not seem to be. Policy solutions could include varying tuition or student grants by degree area in the same manner we encourage select industries with varying tax rates.

Even the objectives of “middle class access” and “higher education infrastructure” are not necessarily related to spending on public institutions.

If the evidence suggests geographical limitations are a problem leading to a deficiency in access and infrastructure, it might still be a more efficient path to the public interest to incentivize private institutions as we do with incentives for business siting in economic development policy.

At any rate, framing public investment in higher education in terms of the public interest would help leaders to develop policy related to accountability, high-demand or performance contracts for higher education.