Orthodox Church in America Diocese of New York & New Jersey Fall / Winter 2023

Harmony Discord

Published with the blessing of His Eminence, The Most Reverend Michael, Archbishop of New York and the Diocese of New York & New Jersey

Editor-in-Chief

Presbyter Matthew Brown

Acting Editor-in-Chief

Nick Tabor

Assistant Editor

Amelia Antzoulatos

Assistant Editor

Samira Kawash

Copy Editor

Deacon David Maliniak

Art Direction & Design

Sophie Ries

Publication Office

33 Hewitt Avenue, Bronxville, NY 10708

Website www.jacobsmag.org

For digital subscriptions and to connect with us on social media, please visit our website.

Fall/Winter 2023: "Harmony and Discord"

Jacob's Well

Opportunities

Want to be a part of Jacob's Well? We are looking for experienced individuals to fill the following positions: Printing Manager and Director of Digital Publications. We are also always looking for writers and artists who want to contribute their work. If you are interested and possess the necessary skills, or if you would like more details about sponsoring an issue, contact us at priestmatthewbrown@gmail.com.

Materials published in Jacob's Well are solicited from its readers voluntarily, without remuneration or royalty payment. The publishers and the staff of Jacob's Well assume no responsibility for the content of articles submitted on this basis.

Material herein may be reprinted with acknowledgement.

Send comments, corrections, or suggestions for potential articles to priestmatthewbrown@gmail.com.

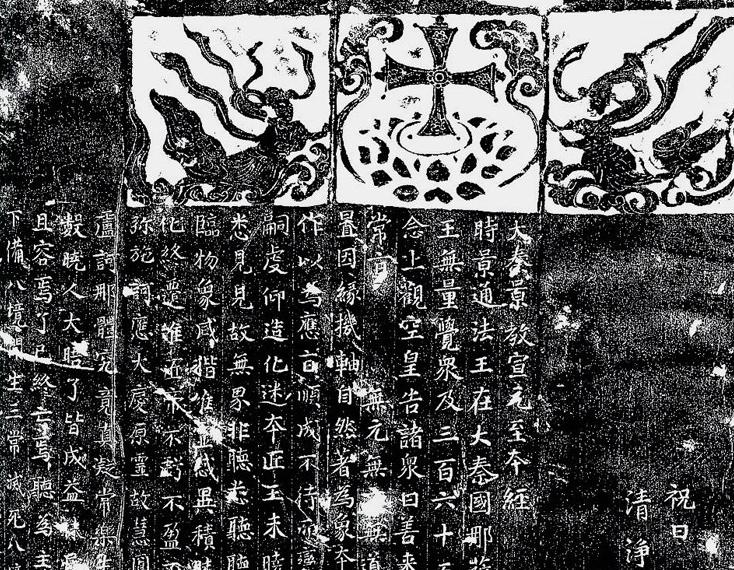

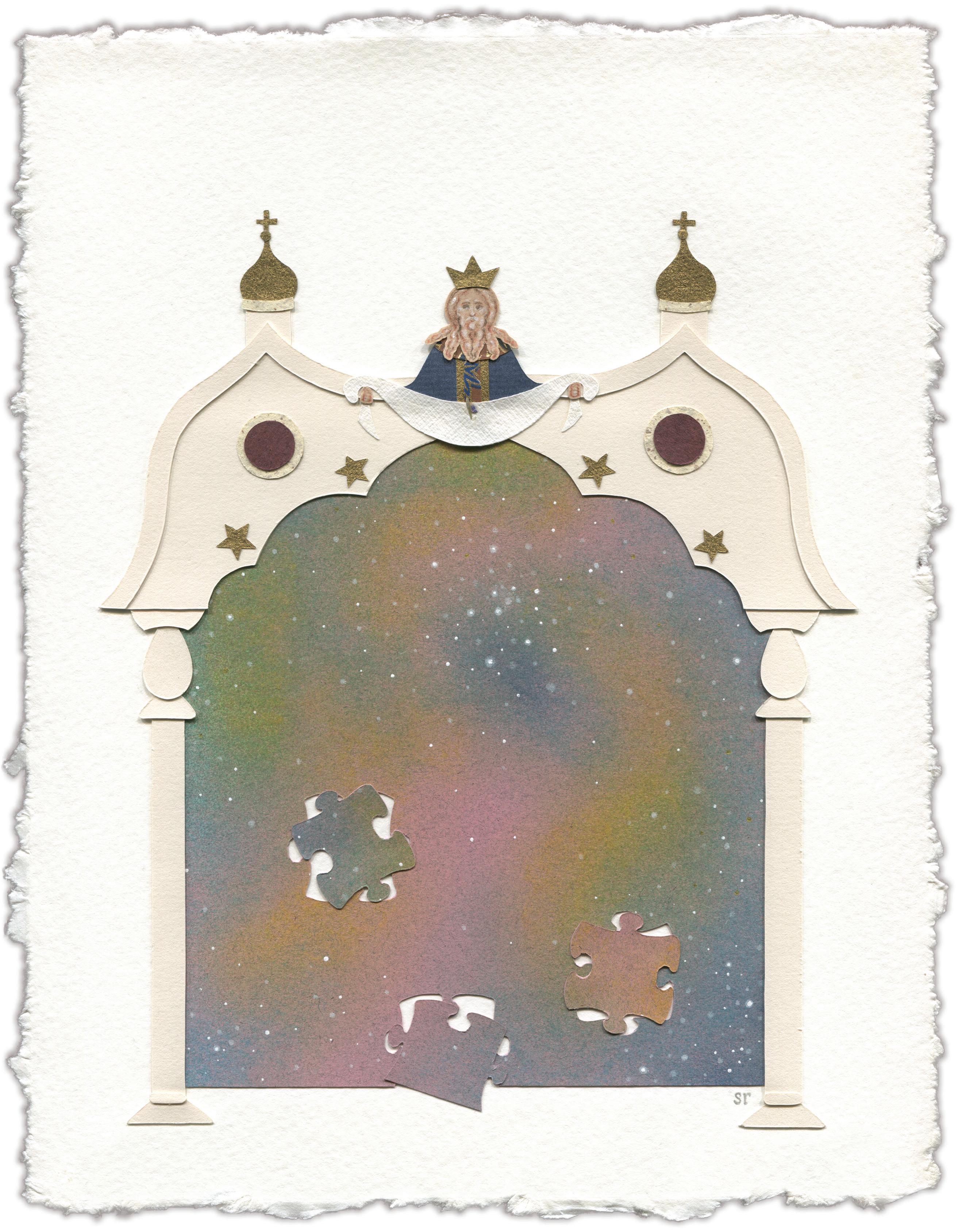

Front Cover

Harmony and Discord (2023)

Sophie Ries

Frontispiece

Attersee (1900)

Gustav Klimt

Back Cover

Plaque with Christ Blessing (ca. 1190–1200)

French, copper and enamel

Letter from the Editor by Nick

Tabor

Life in the Time of COVID by Archpriest

Eric Tosi

Making Faith Come Alive by Kristina

Baktis

Three Days in the Adirondacks

Interview with Presbyter Martin Kraus

Letter From the Catskills by Beatrice Olderog

A Unity of Vision by Doyin

Teriba

In Praise of Dissonance by Benedict

and Talia Sheehan

and Talia Sheehan

War as a Challenge for the Christian Vision by Sergei Chapnin and Presbyter Matthew

Religio as a Universal Human Quality by Jesse

Hake

Achieving Harmony Through Conflict by John

Livick-Moses

Christianity's Asian Future by David

Armstrong

Brown

Contents Daily Bread 40 44 48 52 55 56 57 58 | Family Life | Family Fissures by Amelia Antzoulatos | Theology & Culture | The Two Alexanders in My Life by Archpriest Michael Meerson | Church History | A Measure of Kinship by Presbyter Mikel Hill | Spirituality | Praying for Parking by Samira Kawash | Poetry | Coracle by Scott Cairns Sudden Storms by Sherry Shenoda Watermelon Seeds by Sherry Shenoda | Youth Pages | 2023 Diocesan Graduates Diocesan Life

6 10 12 15 16

4

Feature Essays 18 22 26 32 36

Letter

Editor

by NICK TABOR

The scriptures and our liturgical prayers are forever extolling the importance of unity and harmony. “For the union of all, let us pray to the Lord,” we hear in every litany. The Psalmist writes of “how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity,” and St. Paul urged the church in Rome to “live in harmony with one another.” Likewise, the Proverbs describe “a man who sows discord among brothers” as one of the seven things the Lord considers an “abomination.”

And yet, we all know from experience that conflict is a routine, not to say elemental, part of church life. Even in the best of circumstances, our fellow parishioners’ personalities sometimes grate on us. Parish councils inevitably clash over building projects and other questions of money. And if we’ve been around long enough, we’ve seen priests and bishops get caught up in scandals: perhaps embezzling funds, carrying on extramarital affairs, or even committing abuse or helping to cover it up.

Moreover, in this moment, it’s safe to say that we’re not living in the best of circumstances. The Orthodox world, both in the U.S. and worldwide, seems more divided than it’s been at any other time in recent history. In many American parishes, the COVID pandemic created massive new rifts within congregations, as we disagreed about which safety precautions were appropriate—from suspending services to mandating face masks. Though we’ve all gone back to church now, more or less, and discarded our N95s, those clashes haven’t necessarily been forgotten. No doubt many parishioners think about one another differently now than they did in 2019.

More important, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has been disastrous for ecclesial relations, as Patriarch Kirill and other leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church have rallied in support of Vladimir Putin’s administration. Setting geopolitical questions aside,

it’s been heartbreaking to see images of churches like the Transfiguration Cathedral in Odessa largely in ruins—to say nothing of the tens of thousands of people who have been killed and the millions more who have been driven from their homes. More than a few Orthodox voices have likened the invasion to the sin of Cain. Hundreds of priests in Ukraine, and laypeople around the world, have called for Kirill’s ouster.

In moments like these, our prayers for the “union of all” can sound like nothing more than wishful thinking. We find ourselves confronting an impossible gap between the lofty rhetoric of our church texts and our lived experiences. We’re forced to reflect on what the calling to harmony demands of us in a world of such discord.

To begin with, the analogy to music is helpful here. Musical harmony is a kind of unity that depends on differentiation. It’s a moment of togetherness and individuality at the same time, where the voices neither merge nor clash. Applying this to the church, we might say that disagreements are part of a harmonious community life—they’re not antithetical to it.

In their essay in this issue, “In Praise of Dissonance,” the church musicians Benedict and Talia Sheehan go a step farther, arguing that even too much harmony can be destructive. “In any given piece of music, it is the interplay between consonance and dissonance, the dance between tension and resolution, that creates movement and gives music its sense of direction and meaning,” they write. Extending this to a social context, they argue that when there’s “too much similarity of perspective,” a community can “spiral out of control.”

This interplay is something we especially strive for in the Orthodox tradition. We have less centralized authority than the Roman Catholic Church but a far greater sense of unity than Protestants do. And we celebrate distinct ethnic cultures as an integral part of our spiritual lives, but we try—at least in our better moments—to do this without losing sight of the universal elements of our faith, the ones that transcend ethnicity.

It’s a difficult balance to strike. Some of us tend to oversimplify the Orthodox tradition, to imagine that it’s monophonic. But it has spanned

jacob's well 4

FROM

THE

many cultures over a period of 2,000 years, and it has seldom convened its leaders to issue definitive theological decrees. The bounds of what has been accepted as Orthodox over the centuries—in theology, liturgical practices, and other areas—are broader than we might imagine.

But of course, there are limits. There’s a reason we recite the Nicene Creed at every Divine Liturgy: It’s an expression of our core beliefs as a group, of the teachings that bind us together.

However, even in cases where one party is definitively in the wrong, the conflicts we experience often resolve into a greater harmony. In centuries past, the Church’s very dogma, including its core teachings on the nature of Christ and the process of salvation, were only arrived at after many rounds of intense, often bitter conflicts. The catalyst for each of the Ecumenical Councils—at least according to conventional wisdom—was that false doctrines were circulating, forcing Church leaders to clarify the official teachings.

Of course, only so much depends on us as individuals. What are we to do in the face of catastrophic conflicts like the one centering on Ukraine, where our prayers and personal humility can’t produce accord among our hierarchs—let alone cause the violence to cease?

Sergei Chapnin and Fr. Matthew Brown reflect on this question in another essay in these pages, “War As a Challenge for the Christian Vision.” In the case of the Ukraine war, they argue, almost any hardline position would be misguided. The just-war theory that originated with St. Augustine has no place in Orthodox tradition; “at best, war can be the least bad option in a fallen world.” At the same time, in their view, to suggest that God has condemned all violence would also be a departure from the mainstream of Orthodox teaching. Absolutist ethics like pacifism “overlook the personal dimensions of moral choices,” they argue, “and ignore the moral burdens placed upon each of us to discern what is good in each situation.”

Nevertheless, we wouldn’t want to suggest that all conflicts are beneficial. Within our parishes—and within our families, and among our friends—they can also be destructive and tragic. Generally, our spiritual tradition urges us to look inward, to consider how we might personally be at fault before we level criticisms at others. And when we find ourselves at odds with the people around us, we shouldn’t only ask whether we’re in the right; we should also ask whether the fight is worthy. St. Paul’s words to his disciple Timothy come to mind: “Have nothing to do with stupid, senseless controversies; you know that they breed quarrels.” He goes on to say that a Christian must be “kindly to everyone.”

In his essay for this issue, John Livick-Moses, a licensed clinical social worker, explains that when his patients are having troubles with their partners or family members, they often have better results when they set aside the instinct to criticize, or to defend themselves, and instead approach the other person with genuine curiosity. “I’ve seen many cases where someone’s true motives or concerns are hidden behind other issues in the midst of conflict,” Livick-Moses writes. “By asking questions and maintaining empathetic curiosity, we may realize that a more profound pain is present.”

More broadly, in the face of conflicts beyond our control, prayer is the most fundamental and obvious response—but it’s not enough. “Christians should think creatively about how they might help,” they write, citing the work of Dr. Paul Gavrilyuk and his team at Rebuild Ukraine, who deliver aid to suffering Ukrainians, as one possible model in the present conflict.

Finally, a little historical perspective might help. It can be easy to lapse into sentimentalism about Christian history, to imagine that our forebears worked out their differences more amicably. But since the days of the Church as chronicled in the Book of the Acts of the Apostles, bitter infighting has been as much a staple of ecclesial life as prayer and forgiveness. If we remember that the Body of Christ has survived worst scandals in the past, it might help us stave off despair about the present and future.

5 jacob's well

NICK TABOR is a freelance journalist and the Acting Editor-in-Chief of Jacob's Well. His first book, Africatown: America's Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created is forthcoming from St. Martin's Press. He is a parishioner at the Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection in Manhattan.

Life in theTime of COVID

HOW A CHALLENGE BECAME AN OPPORTUNITY

hen COVID hit, I don’t think anyone foresaw the effect it would have on us as individuals and as parish communities. It is certainly easy to look back now and judge whether we did things correctly, but the reality was that we had to live in the moment. As the new rector at St. Gregory the Theologian, I had to think very clearly and consider carefully how to proceed because it would determine not only how we survived this period, but also how to emerge with an intact parish. This dilemma likely impacted every parish as they faced this unique situation.

At the outset, I established two guiding principles for our path forward and discussed them with the parish and the parish council. First, we would not divide the parish over COVID. There were people on both sides of the issue and their positions covered just about every facet of it (as was also reflective of society as a whole). In whatever position you took, one could be categorized as uncaring or an extremist. This needle had to be threaded very carefully lest it explode in the parish community. Second, and in my mind, more importantly, we would

maintain a semblance of church life in the face of lockdowns and restrictions. You could only do so much, yet somehow you had to keep the church together and move forward. There was no “magic” or simple solution. But I knew we had to do something—anything—and I explained to the parish that we were not to see this as anything but an opportunity. This was our evangelistic moment, and it did, in fact, move us in unexpected ways.

My years of studying, implementing, and teaching evangelism suddenly came to the forefront because the circumstances invoked the same guiding principles seen in evangelism— keeping the church together and functioning as a church. I have always gone back to the church Fathers when confronted with a question, and over the years I have relied especially on St. Innocent’s “Instruction to Missionaries,” in which one can find a plethora of practical and eminently applicable principles.1 One of his principles is that “Methods of instruction may vary according to the state of mind, age, and faculties of him who is to be instructed…to these facts should be adapted the method and

1 For a .pdf, see St. Innocent of Alaska: Instructions to a Missionary (catacomb.xyz)

jacob's well 6

order of instruction in the saving truths.” In other words, know your people and what they can handle and teach and lead them accordingly. It is from this perspective that we stepped up to face the opportunity.

Hewing to the guiding principles I’d established—remaining united as a parish and maintaining some form of church life—seemed to call for the use of technology. Fr. Alexander Schmemann had written in a 1966 essay entitled The Task of Orthodoxy Theology in America Today, “Everywhere, and not only in the West, (Orthodoxy) is challenged by a secularistic,

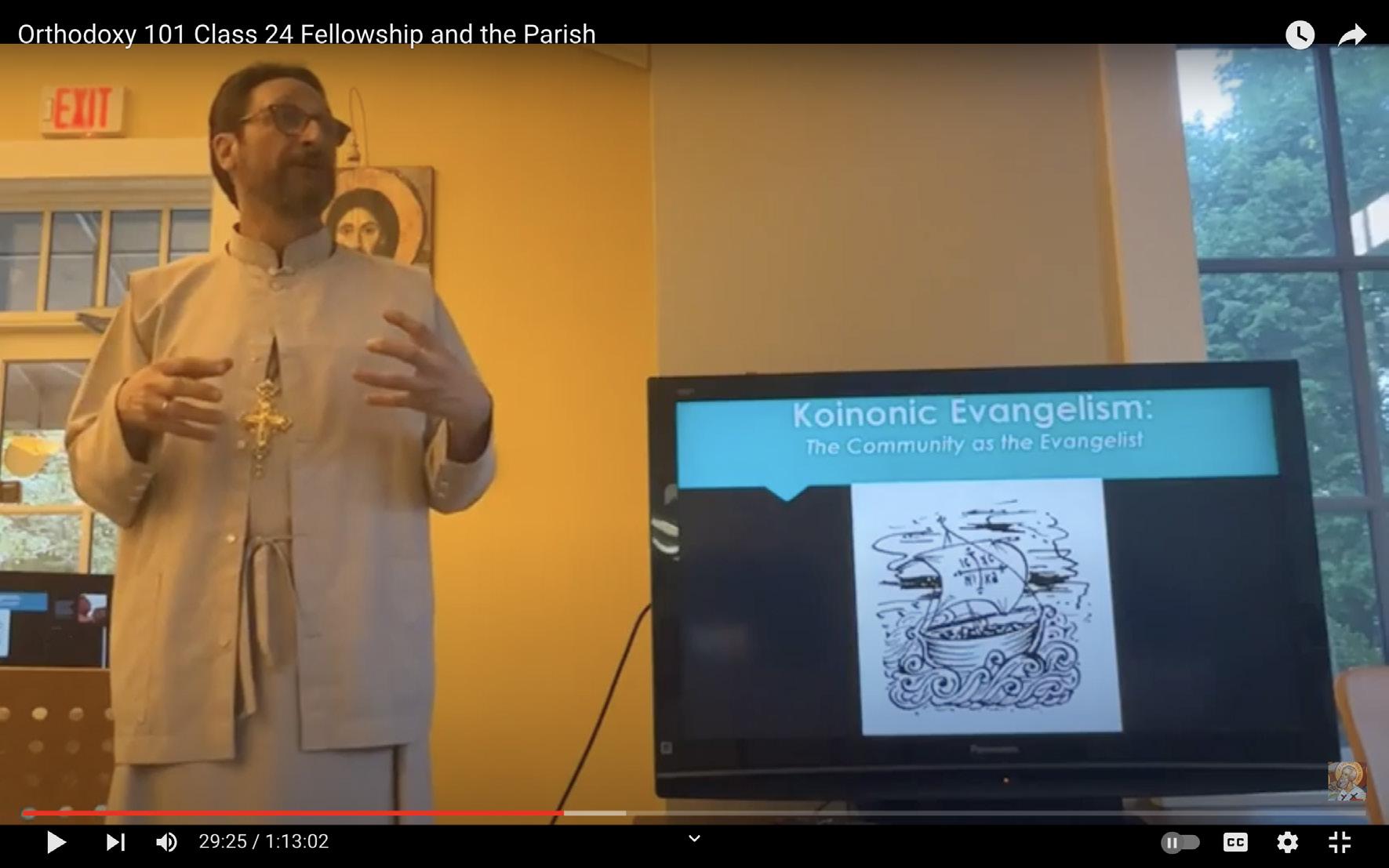

“Orthodoxy 101.” We did what we could in whatever way we could. As for our parishioners, we maintained our sense of community by calling each other frequently and speaking over Zoom. Other parishes were doing the same, so our approach was not unique, but we invested time and effort into this. We were even able to travel as a parish (via Zoom) to Alaska and other places of note in the Orthodox Church. We tried to keep it interesting but, more importantly, relevant and infused with the Church, and this made the difference. We were able to hold the church substantially together and keep the church services as alive as possible.

Meanwhile, outside of our community, many people were experiencing an acute spiritual hunger. No doubt many of them had felt it before the pandemic started, but it seems it was intensified by the isolation that the lockdowns brought on. These seekers wanted a foundational spiritual life—a deeper relationship with God and with a community. Often, they turned to the only venue that was available in those months: social media. As we all know, the internet can be a dangerous place, especially for spiritual

technological, and spiritually antagonistic culture which virtually swallows its younger generation.”2 Yet, St. Nikolai Velimirovich wrote, “Technology is deaf, mute, and unanswering. It is completely dependent on ethics, as ethics on faith.”3 Although both can be true at the same time, how we used technology would be the critical and deciding factor. Was it going to keep us together and move us forward or divide us and destroy our community?

We decided to use technology to live-stream the services on various platforms, even when celebrated only by me and a chanter. I also started a live-streamed instruction series entitled

2 Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann: The Task of Orthodox Theology in America Today

3 Ethics and Technology (orthodoxinfo.com)

7 jacob's well

"There was no “magic” or simple solution. But I knew we had to do something—anything—and I explained to the parish that we were not to see this as anything but an opportunity."

seekers, but it can also be a hub for meaningful connections. It was on the internet that the path of St. Gregory’s coincided with the path of these spiritual seekers. They managed to find us.

We have heard and read much about the new generation of “nones;” that is, people who profess no religious faith of any kind. Many books and articles have been written about them. Some of us have certainly encountered them in our own parish lives. But COVID seemed to allow these “nones” to examine their lives anew and rethink questions of faith. This was a gift to the Church because we had answers to many of their questions.

Meanwhile, perhaps in contradiction to the above statement, there was another phenomenon among a group of seekers which I had seen but not to the level that I have now experienced. Many of these “nones,” as they read extensively about the Orthodox faith, had very little, if any, Christian foundations from which to interpret Orthodoxy. They simply were not raised in, nor had they practiced, any semblance of Christian faith and so when they discovered Orthodoxy, they had many questions as to exactly what the Christian faith is. They were a tabula rasa or “clean slate” on Christianity. This presented a great opportunity because I did not have to undo any presumptions, but rather was able to build up their understanding of God from the very basic foundations. Better to do than undo.

However, these “nones” also were very alert. What they saw had to match what they had read or seen on the internet. They could spot hypocrisy quicker than anything else. What we did as a church community, whether in liturgics, teachings, social outreach, fellowship, whatever, had to match what we preached and taught. Otherwise, they would simply turn right around and leave…and perhaps rightly so. If we claimed to be Christians, then we had to act and believe as Christians.

This meant I had to start by explaining the Trinity, Who and what Jesus Christ is, and why He became incarnate, was crucified, and arose from the dead. Incidentally, this is just what St. Innocent encouraged in his “Instructions:” to start catechesis with Creation, the Fall, and humanity’s need for Christ. He counseled that everything else will follow from that. I spend much time with seekers on these topics before we discuss the Orthodox Church. If we do not know Christ, we cannot know His Church. I’ve found that the new seekers are looking for a Christ who is one of the Holy Trinity—not a good buddy, nor a magician who can make all their problems disappear. This inevitably leads to a deeper understanding of worship and why we Orthodox worship as we do. Finally, it helps them grasp another critical point: that no one can be a Christian alone.

jacob's well 8

As we have noted, the internet gives rise to its own communities. These are fascinating, because they can cover just about any shared interest you can think of (and many you could never have imagined). But in many ways, these communities are ethereal—even though they may feel real. Even when they comprise groups of Orthodox Christians, they can be sources of connection and encouragement, but they don’t form bodies of collective worship. As Metropolitan Kallistos Ware wrote, “As Christians we are here to affirm the supreme value of direct sharing, of immediate encounter—not machine to machine, but person to person, face to face.”

This was the challenge—particularly during COVID, when even our regular parish community could not meet in person. I ended up catechizing one family via Zoom and then chrismating them after the parish reopened. But that certainly was not ideal. Once the seekers were able to come into the church, participate in the worship, and integrate into the community, all the pieces of their informal and formal education came together.

But the critical decision we made early on, to make sure we kept together as a community, even remotely, was the key factor that led to these newcomers joining us. If they had seen infighting and division, it’s unlikely they would have stayed. But instead, as they came to the services, met one

another, and became a part of the community, this led them to desire a deeper relationship with Christ and the Church. They had to be part of the “face-to-face” encounter.

St. Nikolai of Zica, when advocating for the use of English in American Orthodox parishes, once wrote, “We must be super-conservative in preserving the Orthodox faith, and supermodern in propagating it.” I believe we did just that. However, I also try to keep in mind a passage from the Apostle’s first letter to the Corinthians: “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth” (1 Corinthians 3:6). It was not me alone, or the community alone, or even our efforts combined only with those of the seekers, who found the right place at the right time. Rather, it was God who brought them to a place that was ready to receive them, nurture them, and ultimately bring them into the Church.

9 jacob's well

V. REV. ERIC TOSI is assistant professor of pastoral theology at St. Vladimir’s Seminary, the chairman of the Commission on Missions and Evangelism for the Diocese of New York and New Jersey (OCA), and the former secretary of the OCA. He is the rector of St. Gregory the Theologian Church in Wappingers Falls, New York.

Still from an "Orthodoxy 101" video on the parish YouTube channel.

by KRISTINA BAKTIS

Ihave the privilege of leading the Children’s Ministry at Mother of God Orthodox Church in Princeton, NJ. My faith grew out of my participation in the services as a child. In turn, I want to provide the children of our parish with opportunities for their own faith to flourish.

Orthodox Christian worship is experiential in nature, accomplished through participation in the Divine Liturgy. Because the Orthodox Church affirms that a baptized person, even an infant, is a full member of the Body of Christ, children’s participation is essential to the formation of their faith. As Fr. Alexander Schmemann reminds us:

“Only when a particular teaching of the Church—or as we say, a dogma, an affirmation of some particular truth—becomes my faith and my experience, and therefore the main content of my life, does this faith come alive. If one reflects on faith and thinks about how it passes from one person to another, it becomes obvious that what really convinces, inspires and converts is personal experience. This is especially important in Christianity, because, in its essence, Christian faith is a personal encounter with Christ…”1

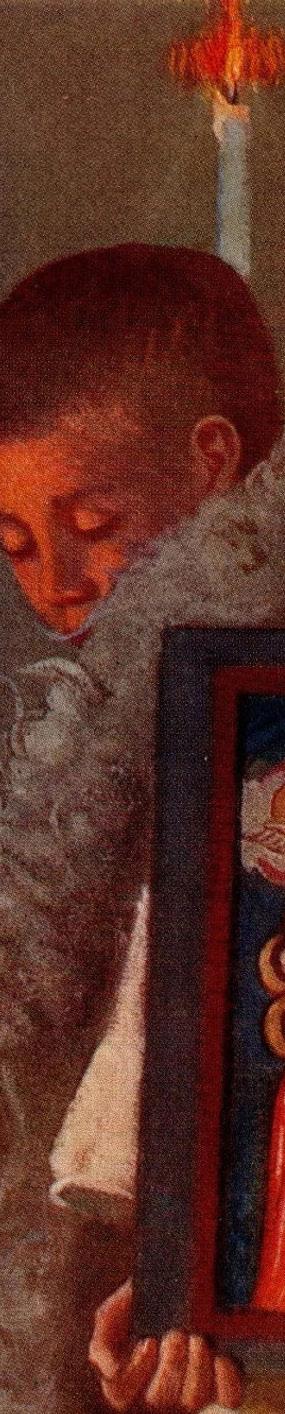

At Mother of God, we are creating opportunities to make “faith come alive” for the children of our parish. The children hold candles during the Little Entrance and Gospel reading, carry icons and candles during the Great Entrance, take the collection, and distribute antidoron. Having these “jobs” makes church meaningful while educating them about their faith. During a Divine Liturgy last year, I recall how a boy waiting for the Great Entrance examined the icon of Christ crucified that he was holding and asked me, “Why did they use nails? That would hurt. They could have used super glue.” This observation opened a discussion about Holy Friday and why anyone would want to hurt Jesus. We also discussed that

because Jesus knows how it feels to be physically and emotionally hurt, He understands our pain and wants to help us.

Throughout the year we combine participation with explanation to orient children and adults to the liturgical cycle of the Church.

On Palm Sunday we connected the hymnology of the church with experience. Before the feast, the children had a lesson to discuss the feast day, the icon, and the troparia. We focused on the role that children played in Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem. Then they made banners that read, “Hosanna in the Highest!” The children took pride in their banners and their role in the service, occasionally waving to their parents and grandparents. The congregation experienced the hymn come alive as children with their banners and “palms of victory” led the way in the festive procession.

For Pascha, the children made banners that read, “Christ is Risen!” They also learned that sometimes it’s ok to be loud in church if you’re shouting “Christ is Risen! Indeed He is Risen!”

During Advent, children learned about the different themes of the fast and preparation for the Nativity. Every week the children would write their own prayer inspired by the weekly theme. Fr. Peter would read their prayers to the congregation while a child lit the candle on the Advent wreath. Their prayers were like petitions recited during the litanies. They included prayers for loved ones, plants, animals, and the planet, and to protect people from the dementors (the creatures in the Harry Potter series that drain humans of their hope and joy). The parish learned the themes of Advent and deepened their own faith and understanding.

In November we connected Thanksgiving to the life of the Church in a lesson called “Eucharist means Thanksgiving.” The children (and parents) learned how to make prosphora. The children discussed what they were thankful for. They wrote down the names of loved ones to pray for, living

jacob's well 10

1 The Celebration of Faith, vol. I: I Believe… Sermons, Volume I. Alexander Schmemann. Translated from the Russian by John A. Jillions. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1991.

and departed, and put them with their prosphora. On Sunday, the entire parish witnessed the vesting of the priest and deacon and the service of Proskomide. Many adults in our parish had never seen this service. The entire congregation was edified because we involved the children in worship.

Participation in the divine services allows us to become a witness to Christ in the world. Fellowship after the service also has a central role at Mother of God, and we have many ways to include children in our vibrant parish life. Our Matronal feast day is celebrated with a fall picnic and decorating pumpkins. In December, St. Nicholas fills the children’s shoes with treats, and they decorate the church's Christmas tree. At our Pascha BBQ, children participate in Easter egg hunts and games. Due in large measure to our active Children’s Ministry, parishioners feel comfortable inviting non-Orthodox friends and family to attend our services and participate in fellowship. Many families hold birthday parties and baby showers at the church, creating a feeling of continuity and wholeness between the spaces of family and faith. These events build community within our parish and witness of our faith to the larger community.

I return to Fr. Alexander’s words: “Only when a particular teaching of the Church—or as we say, a dogma, an affirmation of some particular truth— becomes my faith and my experience, and therefore the main content of my life, does this faith come alive.” After making prosphora, a girl declared, “When I grow up, I’m going to have all the church school kids over to my house and teach them how to make bread.” Making prosphora became her experience and her faith came alive. A living faith that she wants to share with others. May you be inspired to find ways to make “faith come alive” in your community.

11 jacob's well

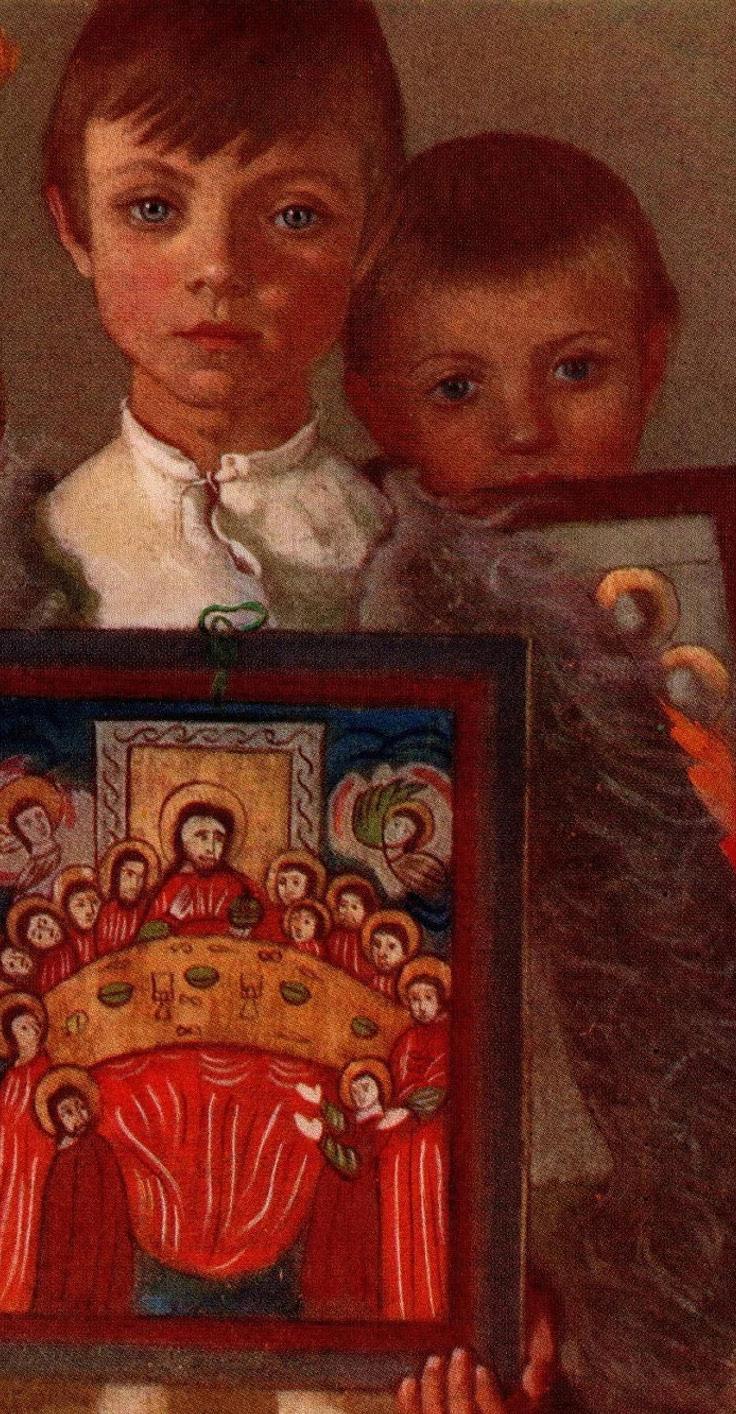

Group in a Romanian Procession (1909)

Marianne Stokes

KRISTINA BAKTIS is a licensed art therapist. She is a member of OCAMPR and a board member of the St. Phoebe Center for the Deaconess. She is a parishioner at Mother of God Joy of All Who Sorrow in Princeton, New Jersey.

Three Days in the Adirondacks

REV. MARTIN KRAUS ON A DIOCESAN CAMPING TRIP

Last fall, men from three parishes in our diocese took a camping trip in the Adirondacks, led by Fr. Martin Kraus. They hiked, made campfires, and conducted Divine Liturgy in the wilderness. It was the first instance of an event Fr. Martin hopes will become a yearly tradition. Fr. Martin joined us to describe the experience and to talk about his love for the outdoors.

To begin with, could you tell us a little about yourself and your parish?

Yeah. I graduated from St. Vladimir's Seminary in 2002. I was the priest at St. Vladimir Church, in Trenton, New Jersey, for five years, and then I came here to Holy Trinity, in East Meadow, in July of 2007. My wife's name is Dennise. We met in college at Drexel University, and we got married in ‘93. We have five children.

As for Holy Trinity, it’s the first Orthodox parish here on Long Island—it was established back in 1924. It's a beautiful community. We have a beautiful property where we hold a festival and other functions for the church.

jacob's well 12

We’re here to talk about the annual camping trip—or retreat?—that you launched last year. How did that come about?

I'm the youth chaplain for the diocese, so I’ve been involved with all the youth events and retreats, and with our summer camp, for about four years now. My wife and I started by helping with a horticulture week the first year. The next year, we were asked if we would be interested in coming for teen week. This year they added a second teen week—so it’s growing.

Last summer, at the end of teen week, Greg Fedorchak and his wife were there helping. Also, there was one of the counselors, Delbert Clement. They were just chatting at the end. We were just finishing up and getting ready to go, and said, ‘Hey, we would love for us guys to be able to do more together.’ They were joking with me, and they said, ‘Do you know a priest who likes to camp, or who might be able to run something like that?’ I said, ‘I think I might know somebody.’ We started talking about it more seriously. Dell was key to the trip, because when he was growing up, he had camped at this Cedar Lakes campsite in the Adirondacks.

Then we were in a mad rush to get ready because it was July when we talked about it, and we actually did the trip in late October. It took a lot of preparation. I was a little concerned about it being too big the first time around. And for first-time campers, I knew it was going to be cold—there would be freezing temperatures at night. We also wanted to make sure we would be able to have Divine Liturgy out there.

Interesting—we’ll come back to that later. But how many people came out for it?

We had 10 guys, between the ages of 16 and 69, I believe it was.

And what did the weekend consist of?

then we did a compline service. Then we had this very interesting experience. We were just hanging around the fire, eating dinner, and this huge, menacing dog showed up. It was sniffing us. Next a bunch of hunters came over. They were camping next to us, drinking beer. They started joking with us, and we got to know each other. We told them we were going to be hiking the next day, and we asked if they knew where to find good firewood. They said, ‘Don't worry about it, we'll take care of it for you.’

The next morning, when we woke up, it was beautiful. The sun was rising over the mountain—I think it was Wakely Mountain. All the grass was white and frosty from the dew and the fresh, cold air.

Later we went hiking up this trail. It was about a five-mile roundtrip. When we came back, we were coming around the trail, and we noticed all the guys over by our campsite. We were thinking, What are they doing? They were chopping wood for us. We didn’t even know these people! It was really special. One of the hunters and I talked for a while about our sons. It was nice to meet strangers and talk about life in general, and family, and just be friendly to each other. That's the camping experience I've always had, and it was nice to have that again, in the Adirondacks.

What was the hiking like?

Well, the first part was marshy and wet. After about two miles, you have some makeshift bridges you’ve got to cross to get over those streams. That last mile up was something else. For the most part, we had no signal at all for our phones—so we didn’t have internet out there, which was another blessing of the trip. But I was a little concerned, because Archbishop Michael wanted to get a message to everybody on the trip. I was thinking, I don't know how I'm going to get this message from him.

We got there on a Friday evening. The most important thing is getting food in you when everybody gets there. I cooked a big pot of vegetable soup for everybody that evening, and

When we were heading up this mountain, the last mile was like going up a staircase. I think it was 1,500 feet up. There were a couple of clearings where we were able to look out and see the view, which is spectacular. I think the elevation there is about 3,700 feet. As you get up to the pinnacle,

13 jacob's well

there’s a 70-foot fire tower, which is one of the highest points in the area. We started getting a phone signal. As we were reaching the peak, a voice message came in from Archbishop Michael.

Wow, perfect timing.

But even more so, because one of the things he talked about was Elijah going to the top of the mountain to speak with God. It was in the small, still voice that he was able to speak to God. It was just a perfect parallel of Vladyka Michael blessing us on our trip. He didn’t know we were on our way to the top of the mountain right then, to see this amazing view.

What a serendipitous moment.

Yeah, it was really special. We spent a little bit of time up on the top, going up the tower. Once you get over the tree lines, you get a beautiful breeze coming over the top, and you have a 360-degree, panoramic view, with nothing but trees and lakes and mountains. No sign of civilization at all. It was just breathtaking.

That makes me want to get out into the woods.

Yeah, I just got back from camping with my own family in the Poconos. We love camping. I had always wanted to do a trip in my own parish, with some of the young men, to help them understand the importance of solitude and being in nature. It's like going back to our home, Adam and Eve in paradise. We can go out into the woods and get recharged and remember how important it is to take care of God's creation—to be stewards. It's something you must experience to really know.

Tell us more about conducting Divine Liturgy on Sunday.

I hauled out this altar table and oblation table and put together a makeshift altar sanctuary. We had the blessing of Vladyka Michael to do it. I got up at the crack of dawn, as the sun was rising. I dressed up the church with her adornments and put the gold covers. It was a very cold morning—it must have been in the thirties. I did the proskomedia as

other people were getting up. It was wonderful to all be together and go through this process of preparing to participate in the Divine Liturgy, as the sun was rising over the mountain peaks. We got a fire going. It was a nice way to finish up the weekend, for sure. After Divine Liturgy, we had our breakfast, and then we packed up and left.

But one of the first things I think of, when I think about camping trips, is the late-night fire, where there are maybe a few guys left, hanging by the fire, and just shooting the breeze. One night, I think

the youngest member and one of our older guys stayed up late. Those are the times when you really build your relationships with people. It creates that connection in a way nothing else really can.

Are you planning to do the trip again next year?

Yeah, in fact, word got out, and I know some people in upstate New York and other parishes, they want to be involved with it. We're hoping to do it in early or mid-September this year, so it won’t be as cold for some of the newcomers.

I think we'll probably have to limit attendance just to keep it controllable. We were hoping for about a dozen people the first time around, and this year we might expand it to 15 or 20.

—Interview by Nick Tabor

jacob's well 14

"We can go out into the woods and get recharged and remember how important it is to take care of God's creation—to be stewards. It's something you must experience to really know."

Letter from the Catskills

A TEEN PARISHIONER ON THE LENTEN RETREAT

by BEATRICE OLDEROG

ALenten retreat provides an opportunity for us to step away from our busy lives and focus on our spiritual growth. It allows us to disconnect from the distractions of daily life and engage in activities that foster a deeper connection with God.

I recently attended a Lenten retreat for teenagers that our diocese offers every year in the Catskills. The weather was much colder than we anticipated, and I didn’t bring enough warm clothes. But the snow-covered hills were so picturesque, it made up for the discomfort. In the end, the chilly temperatures and the heavy snow made the event even more memorable.

While many people may believe that spiritual growth must happen in some serious manner, I believe that fun experiences can also help us in our spiritual lives. This was made possible by this retreat. It consisted of morning and evening services, where we were able to listen to great sermons from a priest. During the day there were activities like candle making and team-building exercises, as well as time to simply relax and talk to others. One of the highlights was a presentation by Archbishop Michael, where he told us his life story and spoke about the history of our diocese. But aside from the formal program, I also enjoyed the chance to step outside my ordinary routine and spend some time in the wilderness. It gave me space for contemplation and personal reflection and helped me reconnect with God.

Besides teenagers from our diocese, there were also people there from Pennsylvania. There was a warm feeling among the whole group, and I

had several lively discussions with both counselors and campers about a variety of different topics. I had a very enjoyable conversation with a counselor about our experiences with different denominations. These discussions provided me with more spiritual insight and made the overall stay much more enjoyable.

In conclusion, I was able to make many connections which will hopefully last me a very long time. The time spent away from my phone provided me with ample room for contemplation. Most notably, I was able to simply spend time in nature while still having an opportunity to dedicate time to God. All in all, I would strongly advise anybody to take part in the retreat.

The Lenten Retreat for the current school year will be at Frost Valley YMCA Camp in Claryville, New York, between April 12 and 14, 2024. Middle School and High School students in grades 8-12 are encouraged to save the dates and attend. Registration will open in January. Announcements will be posted at www.nynjoca.org.

BEATRICE OLDEROG is a sophomore at Acton Academy Verona High School and a parishioner at Saint Mary Magdalene Orthodox Church in New York City.

BEATRICE OLDEROG is a sophomore at Acton Academy Verona High School and a parishioner at Saint Mary Magdalene Orthodox Church in New York City.

15 jacob's well

A Unity of Vision

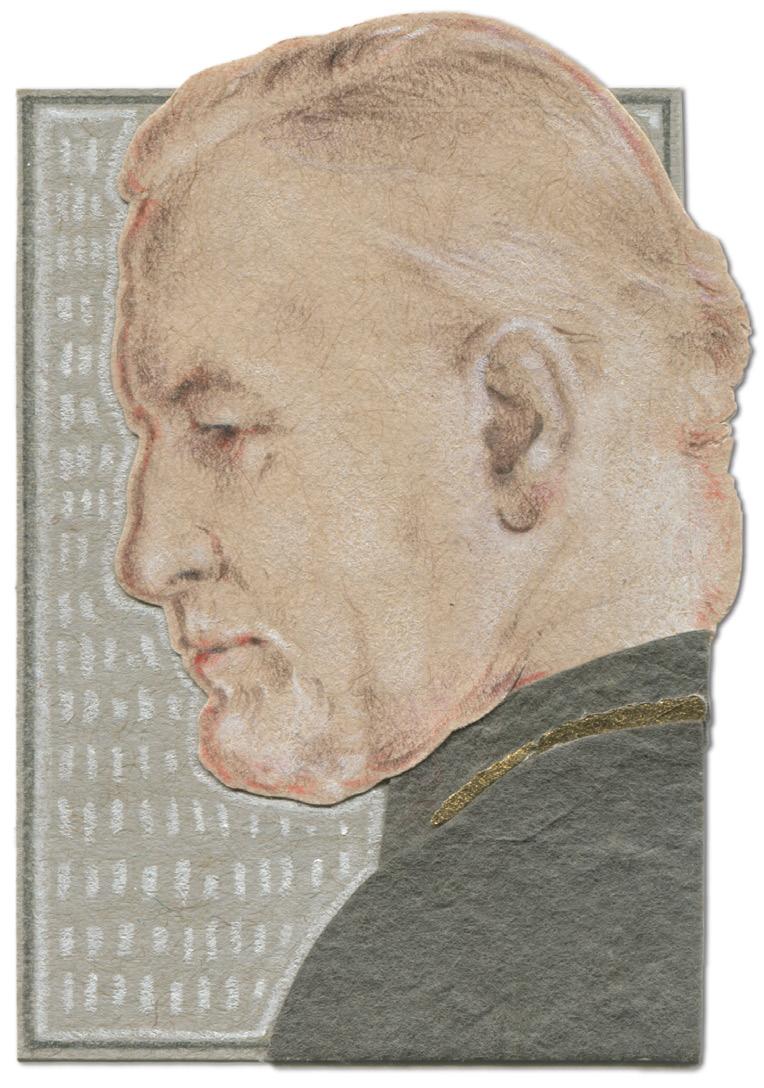

A TRIBUTE TO DR. ALBERT RABOTEAU

argued persuasively that those Christian slaves were part of the suffering church. In other words, he said, they mystically took to heart St. Paul’s words about completing the sufferings of Christ.

Inspired to scour the internet to learn more about him, I found that he was a professor of religion at Princeton University. As it happened, I was then applying to a doctoral program in modern architecture at Princeton. Some months later, I was accepted at the school, and I moved to the Princeton area in the fall of 2008.

by DOYIN TERIBA

H"ave you heard about Albert Raboteau?” a friend asked me after Divine Liturgy. We were in the sanctuary at Holy Trinity, the Greek Orthodox cathedral on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. I was still wearing my cassock, basking in the afterglow of the service. Although the room was almost empty, it still felt full—as if the invisible members of the whole church were still there, even as the other parishioners had left for coffee hour.

I told my friend the name was unfamiliar.

“Here, take this,” he said, handing me a copy of Sorrowful Joy: A Spiritual Journey of an African American Man in Late Twentieth Century America, Dr. Albert Raboteau’s spiritual autobiography. It narrates how Dr. Raboteau, who was born into a Catholic family on the Mississippi Gulf Coast and became a pathbreaking scholar in the field of African American religion, came to embrace the Orthodox Church midway through his life.

Over the next few days, I devoured the book. I was spellbound by his telling of the stories of enslaved people in this country who became Christians during their bondage. It was as if I could hear the slaves’ voices. Dr. Raboteau—or Panteleimon, as he was known in the church—

After getting acquainted, Panteleimon soon became a third father to me—after my biological father (in Nigeria) and Fr. Daniel Skvir, the priest at Holy Transfiguration Chapel in Princeton, where I became a parishioner. Over the next several years, during my most difficult times at Princeton, Panteleimon was a stalwart for me. He comforted me when my mother passed away, while I was writing my dissertation. “My mother passed away too, before I completed mine,” I remember him saying. “I went to her funeral and then returned to finish it.” Those words gave me the strength to continue. In other moments of distress, he would sit with me at the Frist Campus Center, Princeton’s student union building, and listen to my concerns. When I spoke of wanting a “big, juicy” academic position after I finished my degree, he’d remind me to focus instead on the joy of learning, and to find topics I loved.

Panteleimon had great love for others, despite the harm that had been inflicted on him. I heard him speak at least twice, in public presentations, about how he never met his own father, who was murdered by a white man months before he was born. Panteleimon was forthright about his personal struggles. I admired his commitment to repentance and his willingness to always return to God. It explained his patience and gentleness with me.

As he explains in Sorrowful Joy, he was a devoted Roman Catholic for much of his life. He attended college at Loyola University, a Jesuit school in Los Angeles. The Jesuits' stated mission is to “find God in all things,” and the lessons he learned from his professors clearly stayed with him for the rest of his life. They spoke of a “unity of vision,” he wrote, wherein all human knowledge and experience fit into a pattern of meaning that we rarely glimpse. “At the core, tying everything

jacob's well 16

together, we learned, was a simple and yet profound belief: the insatiable desire of the human spirit for knowledge is an expression of our profound yearning for the infinite reality of God.” It was at Loyola that he was inspired to become a teacher.

Over the next several decades, he became a towering figure in the academic world. His 1978 book, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South, remains the definitive study of the spiritual lives of America’s enslaved people. Its impact has been incalculable; it has inspired works in history, sociology, and literature, as well as in Panteleimon’s own field of religious studies.

His conversion to Orthodoxy took place in the 1990s, following a painful divorce. Sorrowful Joy describes profound experiences he had in churches, at a monastery, and at an exhibit of Orthodox iconography at the Princeton Art Museum, all while he was still an inquirer. He was most moved by the hymns he encountered in services. “They had the same sadly joyful tone which I associated with down home and with slave spirituals,” he wrote. After his chrismation at SS. Peter and Paul in Manville, NJ, he played a central role in establishing Mother of God, Joy of All Who Sorrow Orthodox Church in Princeton.

The sense of unity between his scholarship and his faith is remarkable. In Slave Religion, for instance, there are passages that resonate deeply with Eastern Christian theology—which is even more striking because he had not yet joined the Orthodox Church when he wrote it. He argues, for instance, that when enslaved people sang hymns like “Go Down Moses”—which describes the Hebrews’ exodus from Egypt, with the refrain “let my people go”—it was a form of liturgical, sacramental worship. A “sense of sacred time operated,” he wrote, echoing the scholar Lawrence Levine, “in which the present was extended backwards so that characters, scenes, and events from the Old and New Testaments became dramatically alive and present.”

It’s not hard to see a connection with the Orthodox services—for instance, those of Holy Thursday and Friday, in which we mystically partake in the Last Supper and the crucifixion of Christ. “During the Liturgy,” the theologian Paul Evdokimov wrote in 1959, “through its divine power, we are projected to the point where eternity cuts across time, and at this point we become true contemporaries with the events which we commemorate.”

The integrity between his professional life and his faith was also reflected in other ways. Like his patron saint, the third-century martyr, Panteleimon was a healer. He infused his academic discipline with Christian virtues, such as the recognition of the dignity of every human being—grounded in the understanding that each person bears the image of Christ. He exemplified what it means to be a scholar: He knew that if he could pose the right question, it would usually lead to collaborations with others who had expertise that he lacked. He had a knack for bringing scholars together and creating a collegial atmosphere, not unlike the Body of Christ.

Panteleimon was also a master teacher—a teacher’s teacher. He told me once that teaching a seminar was like breaking open the “bread” of the texts that he and the students read. I would venture to guess that from his perspective, the professor and the priest were one. Each invites people to share the joys of being in the kingdom through God’s creation, which is offered to God in thanksgiving. The professor knows that everything is sacred, and that to “break” open a text is to be reminded of that more permanent world where all things will be glorified and transfigured by the One Who Is.

When Panteleimon retired in 2013, Princeton University convened a conference in his honor, and scholars came from around the world. One former student called him “Saint Al,” recalling his gentle and caring mentorship and sweet demeanor. Another, who now teaches at Princeton, recalled receiving a “happy birthday” phone call each year from Panteleimon, who shared the same birthday. As a member of the Princeton Georgian Choir, I had the honor of serenading him with Georgian polyphonic songs during a reception.

He fell asleep in the Lord at the age of 78 in the fall of 2021, after suffering for several years from Lewy body dementia. He was laid to rest at the church in Princeton that he helped establish.

Thank you, Panteleimon, for being my third father. Thank you, Panteleimon, for showing me what a true Christian scholar should be. Thank you, Panteleimon, and pray for us.

17 jacob's well

ADEDOYIN TERIBA is an assistant professor of art history at Dartmouth University. He is a tonsured reader at Holy Resurrection Orthodox Church in Claremont, New Hampshire.

In Praise of Dissonance

REFLECTIONS ON STABILITY, HARMONY, AND TRADITION

by BENEDICT & TALIA SHEEHAN

On November 7, 1940, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge failed spectacularly. That morning, only four months after it had opened, the structure started shaking in the hard wind. Drivers felt their cars sliding around and heard the structure cracking; they barely had enough time to clamber out and sprint to safety. Within minutes, the bridge had collapsed into the Puget Sound.

On the morning of June 10, 2000, the London Millennium Footbridge was opened to the public, and just a few hours later, it started doing the same thing. The builders were forced to close the bridge that same day, and it needed two years’ worth of redesigning and rebuilding before it was safe for regular traffic. What was going on in both cases was a phenomenon known to physicists and engineers as harmonic resonance. Small vibrations within the structures, caused by wind or by ordinary traffic, effectively started echoing themselves— quite literally harmonizing with themselves—doubling in amplitude with each vibration and creating an exponentially increasing wave of resonance that the materials and construction techniques of the bridges were eventually unable to withstand. Essentially, the two bridges fell victim to their own internal alignment.

jacob's well 18

Engineers need to account for harmonic resonance in their structural designs. And the way they account for it is somewhat counter-intuitive. They prevent harmonic resonance by strategically introducing interference—essentially, by creating dissonance within the structure—so that small vibrations don’t infinitely echo themselves. For the two of us, as lifelong musicians, there is a fascinating parallel with what we’ve experienced in our own work.

In music, and especially in vocal technique, harmonic resonance is generally regarded as a good thing. It naturally amplifies sound while at the same time decreasing the amount of energy needed to produce that sound. However, in suspension bridges—or in microphone feedback, tsunamis, or earthquakes—harmonic resonance turns out to be a bad thing, sometimes catastrophically bad. In any dynamic structure that is constantly subjected to subtle changes in its environment—whether it’s a bridge, a building, an ocean, or a network of continental plates—interference is crucial. Dissonance saves the day. Without it, the structure will vibrate with those environmental changes and will amplify its reaction to those vibrations until it shakes itself to pieces.

So yes, harmony is good, but exclusively harmony turns out to be destructive. Every experienced musician instinctively understands this. Music without dissonance isn’t stable, either in its internal structure or in terms of its ability to connect with people and maintain a devoted audience for itself. In musical terms, dissonance may be broadly defined as a set of one or more pitches in which either the fundamental tones or their accompanying overtones interfere with one another in some way. Consonances—or tones that “harmonize” with one another (in popular terminology)—are, by contrast, sets of one or more pitches that align with one another and thereby create harmonic resonance. (And in case you’re wondering, yes, the traditional

consonances, such as unisons, octaves, and perfect fifths, do create more resonance than intervals that are considered dissonant.)

In any given piece of music, it is the interplay between consonance and dissonance, the dance between tension and resolution, that creates movement and gives music its sense of direction and meaning. Without dissonance, music simply doesn’t move—and, by extension, doesn’t really move its listeners. Though exclusively consonant music may appear, at least in theory, to have a kind of monolithic stability on the small scale, it risks its stability on the large scale by coming across as rather obtuse and meaningless, and thus becoming music that no one cares to listen to or remember in the long term. Musical stability, therefore, is a product of tension, a product of oscillation between the static and the dynamic, between the harmonious and the dissonant.

Even in the material world, stability is not fixed and unmoving. In our universe, it is achieved not by restricting movement but by allowing for it. Movement is the fundamental characteristic of existence. All molecules move or vibrate at the atomic and subatomic levels. All organisms maintain homeostasis by moving through intakeoutput and rest-effort cycles. All stable planetary orbital positions are examples of objects in constant, dizzying, high-speed motion. Like a bird balancing on a wire, stability is attained through continuous small-scale movement. Yes, excessive movement is destabilizing. But too little movement is just as destabilizing.

Human communities and institutions, especially religious ones, operate in much the same way. When there’s too much ideological alignment within an institution or community, too much inherent consensus, too much similarity of perspective, ideas and behaviors tend to amplify themselves in a cycle that looks a lot like harmonic resonance. Without a little calculated interference, a little strategic dissonance, that cycle can quickly

19 jacob's well

spiral out of control. It’s no accident that so many cults end up self-destructing in a blazing inferno or in a shoot-out with the FBI, or that so many governments that attempt to realize a vision of perfect alignment within the body politic end up committing atrocities. The best safeguard against catastrophic harmonic resonance within human society is for there to be deliberate and routine interaction with ideas, perspectives, and experiences that differ from one’s own. Essentially, human society needs dissonance to maintain stability.

Within Orthodoxy, as well as in many Catholic circles, today we see a deep commitment to the idea of tradition. An enormous amount of the rhetoric surrounding Orthodoxy, and especially modern conversion to Orthodoxy, involves words like ancient, original, historic, pure, apostolic, or unaltered, and our concept of tradition tends to be heavily colored by such associations. Many Orthodox believers today seem to have constructed an image of tradition as, essentially, a perfect harmony without dissonance. Thus, when they encounter dissonance of some kind within the church— whether in the form of opposing perspectives, beliefs, or modes of behavior, or simply in the form of doubt, questioning, or criticism—they tend to assume that the dissonance needs to be eliminated, that the opposition must be silenced, and that alignment needs to be reasserted at all costs, lest the harmony of the tradition be damaged. However, anyone who has undertaken even a cursory study of church history will probably suspect that such a picture of a changeless, unbroken harmony doesn’t quite match up with the facts on the ground. With a little more serious study, one begins to suspect that any notion of perfect harmony whatsoever is difficult to maintain without some serious editing of the historical record.

What if conflict isn’t necessarily a problem?

What if, instead of thinking of tradition as unadulterated harmony and consonance, we thought of it rather as something in a state of constant motion—continuously oscillating between stasis and dynamism, between maintenance and innovation, between harmony and dissonance? And what if, instead of regarding dissonance within

tradition as a threat to stability, we saw it as an essential saving grace, guarding tradition against the danger of catastrophic harmonic resonance?

In our work as musicians, as well as in our life experience more generally, we have found that if we care about something and want it to be stable and continuous over the long term, we need both to support it and challenge it. We have found again and again that we’re only able to create stability by allowing interference, and even by sometimes deliberately introducing dissonance to mix things up a little bit. Yes, we are aiming for harmony and alignment most of the time. But if we allow ourselves to fall into moving only in a predictable, consonant, regular way, we find again and again that our movement tends to amplify itself and cause destructive resonance.

If we want bridges to safely carry us over long expanses of empty space, they need to have dissonance built into their structures. If we want music to retain our attention and interest, to move us and inspire us, we need to value dissonance as much as harmony. We need to not let ourselves fall into the trap of thinking that only harmony creates stability. Likewise, if we want our traditions to be maintained, to continue over the long term, to offer us a home, to connect us to God and to one another, those traditions need to allow for, and even welcome, dissonance.

BENEDICT SHEEHAN , a two-time Grammy nominee, is the Artistic Director and Founder of Artefact Ensemble and the Saint Tikhon Choir. His music has been commissioned and performed by many of the world’s leading vocal ensembles, including Skylark, Conspirare, the Houston Chamber Choir, Cappella Romana, and the BBC Singers. He is an artist in residence at St. Tikhon’s Monastery.

TALIA SHEEHAN is the co-founder and Program Director of Artefact Institute. She has appeared with noted ensembles Cappella Romana, the Saint Tikhon Choir, and PaTRAM Institute Singers. She teaches voice, music theory, and liturgical music, and directs three children’s choirs and a women’s choir at St. Tikhon’s Monastery.

jacob's well 20

21 jacob's well

War as a Challenge for the Christian Vision

CHRISTIAN HARMONY AND DISCORD IN TIME OF WAR

by SERGEI CHAPNIN AND PRESBYTER MATTHEW BROWN

How should we as Orthodox Christians respond to violence? More specifically, to what extent, if any, should we support and justify violence? Is this ever necessary or even permissible?

Since the outbreak of war in Ukraine 18 months ago, many of us in the Church have found these questions inescapable. They’ve produced everwidening rifts in the global Orthodox world. All told, the emergent responses could be grouped into three major camps. They are:

1. We should just pray for peace,

2. This war is justified, and

3. God has condemned any use of violence.

Is one of these positions the “right” Orthodox position? Is that even the right way to frame this moral problem? We will examine each one of these positions and see whether any of them can be supported by our tradition.

1. We should just pray for peace

It’s not uncommon to hear the statement, “The Church should not be involved in politics.” Since the start of the war in Ukraine, it’s been amplified among some circles of hierarchs and clergy. Something like this is said: “We do not need to understand the political reasons for this war. Our task as Orthodox Christians is to pray for peace.” To this end, prayers for peace were composed in several local Orthodox Churches shortly after the Russian invasion began. Both the Russian Orthodox Church and the Orthodox Church in America prescribed these prayers to be recited each at the end of each liturgy, as well as in special petitions in the Litany of Supplication.

However, in the case of the Russian Orthodox Church, it’s safe to say that these prayers, to put it amicably, have been part of a public relations effort on behalf of the Kremlin. They’re clearly not politically neutral; instead, they exploit the

jacob's well 22

Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

natural desire for peacemaking that many Christians share. They’re like an ideological parasite on a theological host.

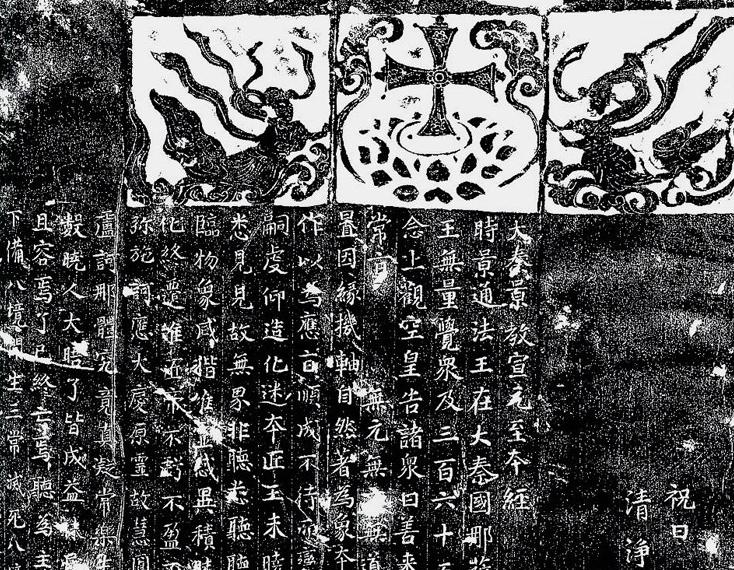

Take, for example, what is now commonly being called the “prayer of Patriarch Kirill” which neatly aligns with the current ideology coming out of the Kremlin:

“From the one baptismal font at the time of the holy Prince Vladimir, we your children have received grace— establish a spirit of brotherly love and peace in our hearts forever! To the foreign nations who would seek to fight and to attack Holy Rus', forbid and overthrow their designs.” 1

The first takeaway, then, is that we should beware of those who would use prayer and peacemaking as cover for ideology. Prayer, when co-opted for an ideological purpose, can be used to halt any judgment of moral culpability, as well as for the starting, escalation, and prolonging of a war. It can stifle us from making moral judgments about the parties responsible for driving the conflict, and no party foreign or domestic is free from such responsibility. Prayer must accompany and strengthen the church’s prophetic voice to call all the worldly powers involved into this conflict to account.

The truth is that this prayer and much of the rhetoric associated with it ignore the reality of Ukrainian cities and towns being decimated by Russian missiles, thousands of civilians being killed, and tens of thousands of Ukrainian children being kidnapped to Russia, not to mention hundreds of thousands of young Russian men dead or injured. Can this behavior of the Russian government—and the Russian Orthodox Church that supports the war—be called brotherly love? Is this what genuine desire for peace looks like?

This brings us to another question. Suppose the admonitions to “only pray for peace” are sincere. In that case, what are we to make of them?

On one level, prayer alone is not sufficient. We are also called to moral action as Christians. Think of Christ’s parable of Lazarus and the rich man, found in the Gospel of Luke. The rich man encounters Lazarus, a beggar, lying at his gate. He ignores him, not even

offering him scraps. If he had prayed for Lazarus, this still wouldn’t have been enough. It wouldn’t have conformed to Christ’s instructions about how to treat “the least of these.”

In the same way, praying for peace cannot be a substitute for right action, but rather a constant companion on the road of working for peace. This doesn’t mean the Church needs to involve itself in political negotiations (although it has sometimes played a valuable role in that arena). But it does mean Christians should creatively consider how they might help. The work of Dr. Paul Gavrilyuk and his team at Rebuild Ukraine, who deliver aid to suffering Ukrainians, is one possible model.

The more difficult question is what we mean by “peace.” Should we be praying simply for violence to stop? Or does a Christian vision of peace demand more than this?

If we examine the Paschal hymns, we see that Christ’s action on the cross, His harrowing of hades, and His resurrection are all cast in the poetic language of conflict. Christianity is not a faith that avoids conflict; rather, it redirects it towards the true enemy: sin, the Devil, and death. These are the “principalities and powers of darkness” that St. Paul speaks of. The appropriateness of violence is another subject, but as to whether conflict is ever justified, the answer is a resounding yes. Real, lasting peace is not a mere ceasefire, but a just resolution.

In many wars—and the conflict in Ukraine is no exception—it’s easy to imagine a version of “peace” that simply amounts to the stronger party indefinitely suppressing the weaker one. From a Christian moral standpoint, this is not enough. This is the third lesson we can draw regarding the “pray for peace” position: there is no true peace without justice.

2. This war is justified

In any given conflict, it’s common for Christians to adopt some version of the just-war theory. For many, this position isn’t the result of rigorous theological engagement; it’s simply the idea that any violence

1 “Circular Letter of Metropolitan Dionysius of Voskresensk on Prayer for the Restoration of Peace,” Moscow Patriarchate, March 3, 2022, http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/5905833.html.

23 jacob's well

committed by their own side is justified in the eyes of God—that their hands are clean. This position has been widely adopted on both sides of the RussiaUkraine war.

The just-war theory in a primitive form was first articulated by St. Augustine of Hippo in the fifth century and later refined by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. In his essay, “Against Faustus the Manichean,” Augustine asks the question, “What is sinful about war?” He answers in this way:

“The real evils in war are love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable enmity, wild resistance, and the lust of power, and such like; and it is generally to punish these things, when force is required to inflict the punishment, that, in obedience to God or some lawful authority, good men undertake wars, when they find themselves in such a position as regards the conduct of human affairs, that right conduct requires them to act, or to make others act in this way.”2

One might see this position reflected in the prayer of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine:

“By Your might strengthen our godly people, bless their deeds, increase their glory with victory over the enemy, strengthen our state with Your almighty right hand, preserve the army, send Your angel to strengthen the defenders of our people, give us all that we ask for salvation; reconcile enmity and establish peace.”3

This prayer is not merely asking for an unspecified peace; rather, it is asking for a peace achieved through victory—as victory is seen as a necessary and justified step toward lasting peace.

But we should ask, what exactly is the standing of the “just-war theory” in the Orthodox tradition?

A lucid answer can be found in For the Life of the World: Toward a Social Ethos of the Orthodox Church, a document issued by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2020. It says:

2 Aurelius Augustinus, Contra Faustum Manichaeum, XXII.74

“The Orthodox Church has also never developed any kind of ‘Just-War Theory’ that seeks in advance, and under a set of abstract principles, to justify and morally endorse a state’s use of violence when a set of general criteria are met. Indeed, it could never refer to war as ‘holy’ or ‘just’. Instead, the Church has merely recognized the inescapably tragic reality that sin sometimes requires a heart-breaking choice between allowing violence to continue or employing force to bring that violence to an end, even though it never ceases to pray for peace, and even though it knows that the use of coercive force is always a morally imperfect response to any situation. … Christian conscience must always reign supreme over the imperatives of national interests.”4

The just-war position can easily become a fiction to justify actions that are unjust. It can also lead Christians to believe that in cases where violence is necessary, their own hands are clean and their souls free of any culpability. No such pristine position exists. Self-righteousness and the proliferation of violence are real dangers of this position, as is blindness to one’s own moral failures committed during a time of war for which an individual or entire people must repent of, and make recompense for.

3. God has condemned any violence

Finally, there are those who believe Christian peace precludes any kind of violence. This position is perennial in the Orthodox tradition. Christian theologians from the pre-Imperial age of the Church can easily be cited in support of this position. Take Tertullian’s brief but capacious formula, written in the second or third century:

“For albeit soldiers had come unto John and had received the formula of their rule; albeit, likewise, a centurion had believed; still the Lord afterward, in disarming Peter, unbelted every soldier.”5

This opposition to state-sponsored violence, however, is not restricted to the pre-Imperial age. It can also be seen in St. Ambrose’s standoff with Emperor Theodosius in 390. That conflict began when Emperor Theodosius

3 “Prayer when the Motherland is in danger,” Ukrainian Orthodox Church, January 29, 2022, https://www.pomisna.info/uk/vsi-novyny/ osoblyvi-molytvy-za-ukrayinu/.

4 “For the Life of the World: Toward a Social Ethos of the Orthodox Church,” Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, March 27, 2020, https://www.goarch.org/social-ethos.

5 Tertullian, On Idolatry, 19.

jacob's well 24

ordered the murder of 7,000 citizens of Thessalonica at the city's hippodrome. When the emperor went to the liturgy in the cathedral, St. Ambrose did not let him even into the narthex of the church. St. Ambrose excommunicated the emperor for eight months, and the emperor accepted this penance. He entered the church and received communion only on Christmas in the year 391.

However, despite these precedents, pacifism has not been the prevailing position in the Orthodox tradition. Christian pacifism is a kind of maximalism, and it’s hard to make this position work in an absolute way while being faithful to our tradition. An inflexible and absolutist ethic is rarely found among the writings of the saints. It is more common among rigorists and schismatics, such as the Novatians, a sect that existed from late antiquity until the eighth century, who believed that any fellow Christians who betrayed the faith under threat of persecution should not be readmitted into the church.

What distinguishes this approach from the rest of tradition, given that we regularly venerate martyrs and passion-bearers who willingly sacrificed their own lives? The difference is that most Church fathers and martyrs have not called for an absolutist standard of pacifism, one that is binding upon all Christians for all times—though it ought be stated that even if our tradition has not unequivocally adopted a pacifist ethic, it has certainly adopted an ethic of peace and strong skepticism towards war.

Moreover, we must be careful about espousing pacifism from our comfortable position in the West, far removed from the devastation in Ukraine, insulated from the difficult personal choices that people have to confront in the face of violence against those dearest to them. To condemn all violence when we’re not in the position of having to accept martyrdom is not necessarily virtuous. These moral questions have a personal dimension that shouldn’t be ignored.

How, then, should we respond?

First, we should recognize that an easy and tidy response is not readily at hand—and that to think otherwise is dangerous. Second, we can safely say that mere prayer is not enough. If our prayers never touch the rest of

our lives and shape our actions, what kind of prayer is that anyway? Third, we should be cautious about declaring any war just. Declarations like these can easily lead to defending atrocities. Wars are complex, and in some cases, military actions that are justifiable can be used as a smoke screen for defending actions that are reprehensible. However, we also need to accept that sometimes ethically imperfect options are the only ones we have. In those cases, we still must repent and make amends for our choices—even if those choices were in large part handed to us by the circumstances.

Finally, we should recognize that absolutist ethics such as pacifism tend to oversimplify complex problems. They overlook the personal dimensions of moral choices, and ignore the moral burdens placed upon each of us to discern what is good in each situation. In some areas, the question of what is right does not come down to a single rule that applies in every situation. Further, such absolutist ethics are an easy temptation for those who don’t have to contend with its costs.

All this is to say that there’s no perfect answer. Unfortunately, to give some kind of step-by-step instruction on how to be the most Orthodox regarding the war in Ukraine would be misguided. At this point perhaps the best we can do is identify moral and intellectual pitfalls. This is more of a negative ethic like negative, or apophatic, theology. The ethical life of a Christian is always this way: it requires us, individually and together, to discern in an ongoing way what seems to be the most Christ-like path in the context of a fallen world. And the best way to do that might just be identifying all the wrong ways instead of the one right way.

SERGEI CHAPNIN is the director of communications at the Orthodox Christian Studies Center of Fordham University and chief editor of TheGifts(Дары), an almanac on contemporary Christian culture. He is a parishioner at the Church of Our Lady of Kazan in Sea Cliff, New York.

REV. MATTHEW BROWN is the editor-in-chief of Jacob’s Well. He is a PhD candidate at Fordham University and the rector of St. Mary Magdalene Orthodox Church in New York City.

25 jacob's well

Religiō as a Universal Human Quality

ON THE HARMONY OF FAITH TRADITIONS

by JESSE HAKE

Modern Christians slip easily into thinking that our faith is in competition with other religions. However, for most of Christian and pre-Christian history, it was widely understood that everyone shared a basic religious impulse and that this was a crucial human virtue, a capacity required for the exercise of our humanity across all aspects of human society. In the first millennium or more of the Christian faith, the various “religions” did not primarily vie with one another—as we tend to do—over claims to dogmatic truth or in earning the right to meet whatever “religious needs” they might have alongside more basic secular or public needs.

Premoderns generally agreed that all humans were religious beings who each needed to cultivate equally the virtue or skill of religiō (as it was called in Latin) within every zone of endeavor, leading to a fully connected and harmonious human life. Given these common goals, different wisdom and folklore traditions could share various aspects of life and learn from each other. Christians, with their universal claims that Jesus Christ is the revelation of the Godhead and of all truth, were best poised to gain insights into the meaning of Christ’s incarnation from the metaphysical and moral insights of other traditions. This is not to say that all traditions are in agreement, or that they are all equivalent paths to God, but it does provide a basis for Christians to seek the flourishing of every

city and to bring all truth, insight, and beauty into conversation and relationship with the revelation of God in Christ’s incarnation.

What was in competition for ancient faiths was not the various ideas or concepts (competing “beliefs” as we tend to think today) so much as the practices, habits, and material culture including the canons of sacred texts themselves and the stories surrounding the ancient teachers.1 All of these sacred practices from varying schools and sects, however, would have been understood as aiming to cultivate the same human virtue of religiō (along with other virtues such as wisdom).2 As with everything else in our modern world, religions have been commodified. They are largely reduced to sets of goods and services offered on the free market and regulated as neutrally as possible by the sovereign secular state. Christians must now lobby beside other faiths on behalf of our “religious rights” and consider what options will best care for any “religious needs” that we might have. Many or most religions have been reduced to just one more means of personal self-care.

Most of the modern categories of “world religions” were developed by scholars from European colonial powers who were influenced by ideas endemic to Christendom as well as by issues related to the end of Christendom and the rise of modernity, the secular nation state, and the autonomous individual. All religions came to be identified over against the realm of the secular,

1 Origen Against Plato by Mark J. Edwards (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2002).

2 Many scholars have told these stories from a variety of perspectives about how the concept of “religions” or “the religious” was invented in the modern era. See The Invention of World Religions by Tomoko Masuzawa, The Meaning and End of Religion by Wilfred Cantwell Smith (with the most explicitly Christian framework of all those listed here), Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept by Brent Nongbri, Imagine No Religion: How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient Realities by Carlin A. Barton and Daniel Boyarin (focused more narrowly on the ancient and Hellenistic past), and 50 Great Myths About Religions by John Morreall and Tamara Sonn.

jacob's well 26

27 jacob's well

Photo: Ron Lach © Pexels.com

and many religions were invented as categories imposed rather artificially from the outside. Hinduism is one of the more obvious examples. When India was occupied by Great Britain, the wide range of philosophies and local folk religions that existed in the subcontinent did not consider themselves to be part of one faith community, but Hinduism was given as a catch-all name by the British colonial scholars. Ironically, despite these European origins, in more recent years, Hinduism has become a focal point for some modern forms of Indian nationalism. Similar trends have deeply reshaped our thinking about all world faiths including Christianity itself.

Before these modern developments, what was notable about the pre-modern understanding of religiō was that various philosophical schools and traditions of cultic practice could all aim at the cultivation of this same human virtue. Certainly, the teachers and sacred texts were in

is the best way to understand the subjugation of all cosmic principalities under Christ that Paul speaks about in several other letters as well. Finally, Paul’s injunction in Philippians 4:8 brings all of us into this task of recognizing and ordering the goodness and truth of Christ that is dispersed throughout creation and across all of history: “Whatever things are true, whatever things are noble, whatever things are just, whatever things are pure, whatever things are lovely, whatever things are of good report, if there is any virtue and if there is anything praiseworthy—meditate on these things.”

real competition—but the fact that they shared recognized common goals made it reasonable to also see that one school or cult could learn and benefit from others in various ways.