SCENE

of the newly designed and relaunched SCENE magazine, a platform dedicated to the exploration of international theatre and arts practice and pedagogy. Our mission is to delve into the creative processes, traditions, and innovations that shape these fields, providing a platform for voices from all corners of the globe to share their stories, ideas, and expertise.

We’re excited to create a space for vibrant conversations about theatre and the arts in all their forms, from ancient traditions to innovative contemporary work. Scene offers a collection of articles ranging from academic writing, artist perspectives, world theatre practices, pathways into the industry, creating new work, and much more.

We also believe that education plays a crucial role in shaping the future of the arts and will explore innovative approaches to theatre and related arts pedagogy, offering insights from leading educators and practitioners. Whether it’s uncovering the nuances of traditional Japanese Noh theatre or examining the intersectionality of performance and identity, Scene is dedicated to fostering a deep and rich understanding of the creative world.

We’re passionate about providing rich insights into what is happening in the global arts scene today.

we explore the transformative power of the arts and storytelling across various mediums. Our contributors share deeply personal and impactful stories of how their work in the creative industries challenge norms, broaden audience representation, and foster inclusion.

Paula Garfield, founder of Deafinitely Theatre, shares her groundbreaking work as a deaf woman in the theatre world. Garfield’s story shows how inclusivity in the arts can radically reshape audience engagement. Kayode Brown, of Just BGRAPHIC, similarly discusses his journey of using the arts to create a movement that empowers marginalised youth. Brown’s work integrates creative expression and cultural awareness into education, providing students with a platform to share their stories while addressing systemic barriers.

Kanako Wakebayashi provides a look into traditional Japanese arts through her perspective as a cultural ambassador. Kanako highlights the transformative power of storytelling and the ways in which Japanese traditions, like Noh theatre, are being promoted internationally through workshops and performances.

Terence Makapan shares his journey as a queer South African artist who has used theatre as a tool for self-discovery and healing. He emphasises the importance of using performance not only to tell stories but to open conversations around identity, race, and the challenges of being a queer person of colour. This theme of diverse storytelling is echoed by Alejandro Postigo, whose project ‘Copla: A Spanish Cabaret’ seeks to bridge cultural divides and celebrate the emotional power of Copla music as a means of expressing queer and migrant narratives. Similarly, Kate Matzopoulos’ article explores the significance of storytelling in Indigenous education, emphasising its role in fostering deep connections with nature, culture, and community.

Helen Abbott Editor

Turning to film and her way into the industry, Alice Powell, film and documentary editor, reveals the complexity of shaping narratives in long-form documentary filmmaking. From her work focusing on NASA astronauts to a feature on Aubrey Gordon (Your Fat Friend), Powell discusses the balance of truth and storytelling as she works with real-life subjects and diverse topics to build empathy and engagement. Michael Graller also reflects on his extensive experience in the costume industry, emphasising the importance of adaptability, collaboration, and continuous learning in roles ranging from dresser to costume shop supervisor at Playwrights Horizons, showcasing the multifaceted nature of storytelling in both theatre and film.

Furthering the conversation on audience representation, we explore how institutions are evolving to address inclusivity in the arts. These initiatives raise important questions about how far we must go to create theatre spaces where underrepresented communities can see themselves reflected and feel they belong. The work of Iketina Danso and Hint Wien (Highly Intersectional Vienna) takes this discussion to the international stage, focusing on queer-centred, intersectional storytelling to make arts institutions more reflective of the world outside their doors.

Collectively, these stories illustrate how the arts can challenge norms, redefine spaces, and create meaningful connections across cultures and identities. Each contributor shows us that the arts are not just about entertainment, but about fostering empathy, inclusivity, and social change.

I hope you enjoy delving into this issue of Scene and that it sparks curiosity and brings new perspectives. Enjoy!

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Justice

Paula Garfield

In this powerful article, Paula Garfield, founder of Deafinitely Theatre and recent MBE recipient, shares her inspiring journey as a deaf woman breaking barriers in the theatre idustry, highlighting the importance of deaf-led productions, British Sign Language, and creating inclusive spaces for both deaf and hearing audiences.

Academic / Theoretical Kate Matzopoulos

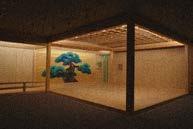

Profiles Kanako Wakebayash

In this article, Kate Matzopoulos explores how Indigenous storytelling serves as a powerful educational tool fostering deep connections with nature, ancestors, and communities, while embracing contradictions and promoting the transmission of knowledge across generations and cultural differences.

In this article, Kanako Wakebayashi shares her personal journey growing up immersed in traditional Japanese arts, the challenges of preserving Noh theatre in a modernising society, and her efforts to promote its tradition both in Japan and internationally.

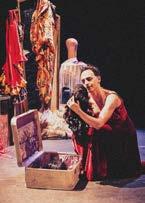

Professional Alejandro Postigo

Copyright: ISTA Lakeside Offices

The Old Cattle Market Coronation Park

Helston, Cornwall TR13 0SR United Kingdom

In this compelling article, queer migrant artist Alejandro Postigo shares their passion for Copla, an evocative Spanish musical tradition that speaks to resilience, identity, and cultural connection.

Pathways

Alice Powell

In this insightful piece, film editor, Alice Powell, shares their journey through the world of documentary filmmaking, emphasising the unique challenges of crafting narratives without a script, balancing truth with engagement, and exploring diverse subjects ranging from NASA astronauts to human trafficking in Nepal.

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Justice

Iketina Danso

In this thought-provoking article, the discussion centres around the urgent need for theatre institutions to broaden audience representation by embracing intersectional and inclusive approaches. Highlighting successful examples such as Hint Wien’s arts education programmes, Iketina Danso emphasises that creating spaces for co-creation, collaboration, and active participation is key to redefining the theatre experience and reaching diverse audiences.

Profiles

Kayode Brown

In this inspiring article, Kayode Brown shares the powerful journey behind Just BGRAPHIC, a transformative arts movement that bridges culture, education, and community empowerment.

Pathways

Michael Growler

Spotlight

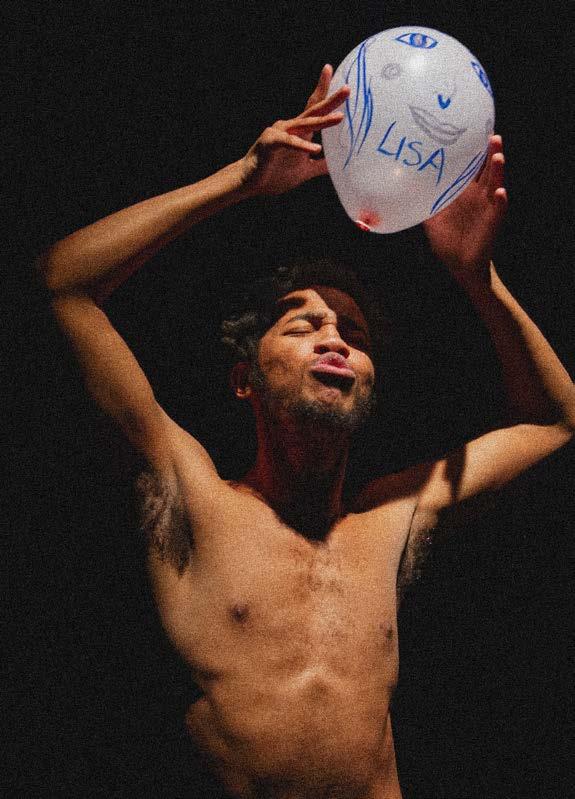

Terence Makapan

In this deeply personal and reflective article, Terence Makapan delves into his journey as a writer and theatre director, sharing how creativity has been both his refuge and his means of self-discovery.

Michael Graller, costume designer and supervisor, shares his journey through a dynamic 30-year career in the world of theatre, film, and television.

By Paula Garfield

Earlier this year, I was awarded an MBE for my services to theatre. I never thought I’d be here. I’m a deaf woman from North West London who grew up with very little language and was in mainstream education where I was not allowed to use sign language. I left school with minimal qualifications and I felt like a failure because I couldn’t read, write or speak well. Theatre saved me. It gave me a place where I belong. And I can use my language of choice – BSL –British Sign Language.

It was in 2002, when I had a chance meeting with Jo Hemmant, an arts officer for Arts Council England (back then). She said, ‘you should set up a theatre company’. I’d met Jo and shared my frustrations at the lack of deaf-led theatre productions. I’d been a jobbing actress for over ten years and was on the verge of giving up after too many projects where I was the only deaf person in the production. Many think that putting one deaf person in a production means it’s suddenly accessible to everyone, this is not the case. The one deaf actor cannot be responsible for the entire show’s access – it doesn’t work. I’ve been in that position and it’s exhausting. What I wanted was to work in a deaf-led space. I wanted to be surrounded by others who share my culture and my language – British Sign Language.

So after this chance meeting, I applied for my first grant from the Arts Council. I got £7,000 to make a play – Deaf History. We performed at the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill Gate in London. All performances were sold out. There was a queue of people outside wanting to see the play. This was with no publicity. This was word of mouth/word of sign! Deaf people wanted to see a play performed by deaf performers that put BSL centre stage. Not with someone standing over to one side, but with actors using BSL and sharing stories from the deaf experience. I contacted Camden People’s Theatre and they welcomed us to perform there. Again the shows sold out.

This proved the demand for deaf-led work.

Deafinitely Theatre was born.

We’ve been running as a company since 2002. We stage one main production a year and a family show every two years. We’ve also run DYT (Deafinitely Youth Theatre) since 2010, with a summer residential as well as one production per year. We realised there was a gap for deaf young people in attending Youth Theatre with other deaf people. We also do consultancy work with other theatres about working with deaf actors and deaf equality training. Another part of our work has been providing training for deaf actors and other theatre professionals. We’ve run the Hub programme for many years to develop skills in all areas of performing, writing and other theatre skills. We want to give opportunities to deaf people interested in all areas of theatre. My long term goal is to have a Drama school course for BSL using actors to do a three year BA in performance in London (there is a course that’s been run twice in Scotland). We’re currently working with Central School of Speech and Drama in London and have just done a week long taster in July 2024. We are planning to do more.

I am proud to say that Deafinitely Theatre has led the way in inspiring more deaf actors and theatremakers. The number of deaf and BSL using actors has grown rapidly from a handful back in 2002 to at least over 100 now in 2024.

When Deafinitely Theatre was first set up in 2002, we did a lot of devised work. We wanted to shine a light on issues affecting deaf people. We produced plays such as Motherland about deaf people’s experiences in the Second World War and Double Sentence, about the experiences of deaf people in prison. We then altered our programme to adaptations of plays such as 4.48 Psychosis by Sarah Kane, Grounded by George Brant, Contractions by Mike Bartlett as well as two Shakespeare plays – Love’s Labour’s Lost and A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Recently, post COVID, we’ve returned to our devising roots with plays including Everyday, about deaf people’s experience of domestic abuse and The Promise about deaf people’s experiences with dementia. We want to create work that starts conversations about important topics. We do extra activities around our productions to engage with our audiences, academics and organisations in the respective fields. We recently held a world café day event on deaf people with dementia to have these important conversations.

Our work always has deaf people front and centre with deaf people involved in the process on and off stage. It’s so important to me to create a safe space. I want the experience to be fully supported for all involved.

I wanted to be surrounded by others who share my culture and my language.

The main language of our work is BSL but all our plays are bilingual. They include English in some form. This could be with some spoken English performed by actors. This also can be through written English and the use of creative captions that are a part of the set/video design. We’ve done some great experiments in this area to make our productions enjoyable as well as accessible for deaf and hearing audiences. We use a lot of music and sounds in our plays. We want to welcome the hearing audience too. In both of our Shakespeare plays at the Globe, we had live musicians on stage underscoring the scenes.

I’m often asked to consult on mainstream productions that include a deaf actor or actors. We try to provide support and guidance where we can. Yes, mainstream theatre has come a long way since my experiences as a jobbing actor in the 1990s. But there is still a long way to go. I’ve seen many productions directed by a hearing person that include deaf actors. Whether it’s one or a few, for me, often, this doesn’t work. The deaf performer must ‘interpret’ what a lot of other characters are saying. Usually, they’re doing this whilst also being a character themselves. This is hard. Sometimes they are not even given any translation support. They are thrust a written English script, and the expectation is that if they can sign, they should be able to translate the script. Translation is a lengthy process that needs time and support with someone being able to explain the meaning, the nuances behind lines, and also the director’s interpretation of the vision.

We need to see more deaf directors leading work and working with associate directors who are hearing. We need to see more deaf voices leading and on the stages. We need more deaf writers/creators of plays that shine a light on the issues that are faced by deaf people everyday. I’d love to see the theatre industry open more doors to put plays written by deaf people on their stages. Deafinitely Theatre has been working since 2002 and there is always a challenge within the theatre industry to find acceptance for deaf-led work.

I only hope with the BSL Act of 2022 and the new BSL GCSE coming from September 2024 onwards, we’ll be seeing a momentum shift. I hope theatres across the country will be more accepting of plays written by deaf people and directed by deaf directors. More doors need to open. Things have improved but there’s still a long way to go.

By Kate Matzopoulos

‘At the time of the first James Bay hydro-electric development in northern Quebec, a Cree elder was brought to story (testify about) Cree ways of life and environment to stop this project, probably to invoke the promise of many First Nation treaties, “as long as the river flows...” ’ (Chamberlin, 2003, p. 68.) ‘When the elder was asked if he would tell the truth, the truth being translated as something that holds for all and that remains accurate irrespective of who was telling it, he responded by saying that he could not promise to tell the truth, but only what he knew’. (Castellano, 2000)

In the unfolding stories below that describe Indigenous education and the centrality of storytelling to it, I will call upon a few of the nine stylistic qualities of African storytelling: Imagery, allusion, symbolism, repetition as parallelism, piling, association, tonality, ideophones, and digression (Okpewho, 1992). Rather than explain the how, my intention is for the living breathing stories (Phillips and Bunda, 2018) to convey the why, which lives in the heart, to say what I cannot. I can only tell what I know, the stories can tell all.

Indigenous education acknowledges, accepts, allows, and actively teaches a deep connection with nature, our ancestors, and each other. It is with these instilled connections that travelling can occur, moving from positions of living from nature to living in nature to coming to oneself as nature (Shikongeni, personal communication, February, 2024). It is through lived experience that Indigenous people, whose education is rooted in their culture and their practice of daily living, transfer knowledge (Marti, 2019). The success of Indigenous people and their transference of knowledge through their educational systems, over many generations, surviving thousands of years despite historical and continuous infringements on their way of life, can largely be attributed to storytelling.

‘About three years ago, I spent time learning from and with the Ju/’hoansi in Nhoma, Namibia. Together we developed a new learning framework, one that can hold Indigenous Ju/’hoansi knowledge holistically rather than in a supplementary fashion. The elements that make up our framework (preparedness, collaboration, flexibility and reflection) emerged through intensive conversation (storytelling), and learning with the land as “a teacher and a co-learner”.’ (Stein, 2019, p.13) ‘I saw myself as a learner in the group of children and adults that went out into the bush. I was able to experience first hand what “education” looks like for the Ju/’hoansi, in their way. By experiencing it – I came to understand what Megan Biesele (1993) explains about the interconnection between teaching (n!aroh) and learning (n!aroh) for Indigenous communities like the Ju/’hoansi. I found that the focus of my learning experience was not on controlling what was learned, but to allow everyone to learn what they needed to in the opportunities that presented themselves.’ Biesele clarifies, ‘Indigenous Ju/’hoansi education comes without a “verbal recipe or set of articulated procedures” but rather as “an example... transmitted in the environment

at the time a learning task is accomplished”.’ (p. 57) ‘Storytelling facilitated and enabled the connection I formed with this knowledge and with the community in Nhoma, allowing the bridging of the gap between otherness.’

Storytelling extending across differences is possible because stories house contradictions. In stories exists the constant consultation between reality and imagination, between individuality and collectivity.

Biesle (1993) explains the pull between individuality and collectivity in Ju/’hoansi society and storytelling: It is difficult to emphasise enough the great latitude for individual artistry granted among the Ju/’hoansi, whether in folktale form or in embellished narratives of everyday experience. The Ju/’hoansi have a “high tolerance for individual contribution” in storytelling and in being, “which may also be related to the egalitarian nature of their society... norms are enforced not by dogma but by the creative participation of all members. “There are many different ways to talk. Different people just have different minds”, is how !Unn/obe an old Ju/’hoansi storyteller explains the possibility of the contradiction of a story being viewed as a faithful retelling but at the same time told differently depending on the teller and the performance the situation calls for (pp. 66- 67). With the acceptance of contradictions in stories and the way they are held differently by different people, can come the acceptance of allowing difference to sit next to each other outside the story too.

Chamberlin (2018) reminds us that ‘accepting the challenge of metaphor presented to us by stories is what can prevent the deterioration of myth into ideology, religion into dogma and communities into conflict’ (p. 34), and is what can create connection with the other across the globe’ (Phillips and Bunda, 2018, pg. 10).

Facilitating this connection through the building of a pedagogy of storytelling can be achieved with theatre (an elaborate form of storytelling). It was at an ISTA theatre festival held in Namibia, that the first steps towards a pedagogy of storytelling were made. Here the contradictions of simultaneously encouraging access to the transcendence (Simola, 2024) and defence of difference was embodied through the telling of a San story. It was enlightening to see both Indigenous San Ju/’hoan and non-Indigenous storytellers - N‡amce Freddy Nqeni, Desta Hailé and Daniel Sarstedt tell a San story collectively with everyone who was present, where differences of age, language, and race were transcended and at the same time, the situatedness of the story celebrated; creating connections with getting comfortable in the contradictions.

‘Because the Elephant Girl could foretell that danger lay ahead for her in the journey she was called to take, she devised a plan and shared it with her grandmother. She told her grandmother, “Stay watchful: a little wind holding something in it, will come to you. The little wind will bring you some droplets of blood, which will stick itself inside your groin. Take that bit of blood and put it into a container. Say nothing about what you’re doing – just take it and put it into something. Something like a little dish or a little bottle.” It was good that Elephant Girl brought her grandmother’s awareness to this, because it so happened that when she was killed, her blood was able to travel to her grandmother on a little wind and sit in her grandmother’s groin. The grandmother, in her heart said, “Didn’t the child tell me such a thing would happen?” With this remembrance, the grandmother put the drops of blood in a little bottle and watched it grow. It grew too big for the bottle, so she moved it to a skin bag. When the bag burst, the grandmother put it into something bigger. The grandmother alone knew this secret and she kept it. No one else knew that she had the Elephant Girl everyone believed dead with her and that she was restoring her to life.

With each growing, the grandmother would fix it until it had grown completely into a woman again, one who looked exactly as the Elephant Girl looked before. When she was completely grown, the grandmother took her and dressed her in new skin clothes, tied copper rings in her hair and hung ornaments all over her. This is how the Elephant Girl came to defy death and live to avenge herself.’ (adapted Ju/’hoansi story shared with Biesele, 1993).

Sharing stories in the ways described above distributes the tolerance of difference, encourages working together, drives creativity, promotes helping each other, and empowers the enjoyment of contradiction and therefore being human.

With stories, solutions to any challenge and oppression can be found, even overpowering death.

Biesele, M. Women like Meat. Johannesburg, South Africa: Witwatersrand University Press ed., 1993.

Castellano, M.B., Updating Aboriginal Traditions of Knowledge. In: G.J.S. Dei, B.L. Hall, D.G. Rosenberg, eds. Indigenous Knowledges in Global Contexts. Multiple Readings of Our World. Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2020 pp. 21-36.

J. Edward Chamberlin. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Vintage Canada, 28 May 2010.

Marti, S., Indigenous Education The Call Of The Territory [Online]. Indonesia: LifeMosaic Publishing, 2019. Available from: www.lifemosaic.net/images/uploads/The_Call_of_the_Territory_Book_(LowResolution).pdf [Accessed 25 August 2024]

Phillips, Louise Gwenneth, and Tracey Bunda. Research Through, with and as Storying. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, Routledge, 2018.

Shikongeni, N.P., 2024, February. Personal communication [Discussion]

Isidore Okpewho. African Oral Literature. Indiana University Press, 1992.

Simola, S., Storytelling as Pedagogical Practice in Support of Transcendence and Well-being. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 2024. [Online] 21(3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.51327/XRQG5211 [Accessed 25 August 2024]

Stein, S., Beyond higher education as we know it: Gesturing towards decolonial horizons of possibility. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 2019. [Online] 38. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11217-018-9622-7 [Accessed 25 August 2024]

Born and raised in a family of traditional Japanese arts practitioners, I have been surrounded by culture and the arts since my childhood. My father is a fourth generation actor of Noh Theatre (a traditional Japanese theatre form) and my mother is a third generation tea ceremony teacher. Like many children whose parents are professional Noh actors, I first performed on the stage at the age of 3, and spent the next 10 years performing as a child actor.

After entering university, I worked part time managing art festivals and exhibitions and helping my father organise Noh workshops, which attracted me to the role of coordinator between art and society. While Noh is an expression of the Japanese religious beliefs of Buddhism and Shintoism, modern Japanese people are becoming less and less familiar with ancient Japanese values, traditional culture and art, and the number of cultural successors and supporters is dwindling. Thus I became keenly aware that I wanted to work to promote Japanese culture, both domestically and internationally. However, as the role of arts manager was not yet widely recognised in Japan, and the knowhow and methods of the job were still unestablished, I enrolled in a Master’s programme at a university in London to study arts management as a systematic discipline. After a year of study abroad, I have returned to Japan to support my parents’ activities, and to promote Japanese culture. In addition, as a performer, I also regularly perform on the stage in the female performing art form of the 11th century, Shirabyoshi, which influenced the development of Noh.

My parents’ and my practice is based in a building called Shinyo Kaikan, which is a complex with a tea ceremony room on the ground floor and a Noh stage in the basement. My parents practise themselves and teach amateur students there. While the tea ceremony is generally known as a traditional Japanese lesson, not many Japanese know that Noh can also be learnt. Many people seem to think of it as something special and that only professionals can learn the skill. However, during Japan’s postwar period of rapid economic growth, utai, which is just a form of Noh singing, became so popular among office workers that companies started their own Noh clubs, and the boom encouraged many housewives and students to enjoy it as well. The number of people who enjoyed utai declined rapidly with the bursting of the bubble economy in the 1990s, but there are still many professional Noh actors who teach Noh to amateurs.

Students range from a first year primary school boy to a 96 year old lady, including people of all ages and both sexes.

My father’s amateur students range from a first year primary school boy to a 96 year old lady, including people of all ages and both sexes. Some of them have been practising Noh for decades, even since my great grandfather’s time. In addition to utai, Noh practice also includes shimai, which is the dance part of Noh. Some people who have developed their skills through years of practice even wear Noh masks and perform Noh in full, just like professional Noh actors. Everyone has their own reasons for learning Noh but they all have one thing in common: they are very powerful. I think the reason why many of my father’s students are still going strong even at their age is because Noh is a verbal and

physical art form, and its practice provides good stimulation for both the body and the brain. I believe that one of the important roles that Noh can play is to allow people to make time in their hectic daily lives to reflect on their own minds and bodies through the practice of Noh.

In addition to these training opportunities, the Shinyo Kaikan also holds workshops for Japanese and foreigners. Before my father plays the leading role in a Noh performance, as a preliminary lecture, we show the costumes and masks used on stage and explain the performance. As Noh developed in the 14th century and deals with the classics, the language used in the play is old, and not many people, even Japanese, can understand the content of the play at first sight. Furthermore, many people have no experience of visiting a Noh theatre, which makes them somewhat dismissive of the space. For this reason, the preliminary lectures not only explain the performances but also provide information on the etiquette of visiting a Noh theatre, and how to better enjoy Noh. To solve the serious problem of the ageing and declining number of Noh viewers in recent years, we believe that it is important to first make people aware of Noh, and then create an opportunity for them to see a performance. What is a familiar space to us is full of mystery for foreigners.

Recently many of my international friends have visited Shinyo Kaikan. Unlike the old opera houses in Europe, the Noh stage is not elaborately decorated, just a square stage made of cypress wood and a large painted pine tree in the background. However, each of these elements has its own meaning, creating an imaginary space. What is a familiar space to us is full of mysteries to foreigners, and every question we receive from them highlights the differences in thinking between cultures, which is very interesting.

Although there are not many opportunities to perform Noh overseas, my father has participated in Noh events in various cities in Europe, America, and Asia.

Most recently, during my stay in London in 2023, I organised lectures and workshops on Noh at Japan House London and SOAS, University of London. It was my first experience of bringing a project to overseas institutions, but the event was so successful that it was fully booked within two days of application opening. As Japanese culture is often imported overseas in the context of subcultures such as anime and Manga, it was a pleasant surprise to me and my father that so many people in the United Kingdom were interested in traditional Japanese performing arts.

In May of this year, in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, my father and his company performed a new Noh play of the story about the Taoist goddess Mazu. At the request of the audience, they gave a curtain call, which is rarely given in Noh performances. The piece was received very favourably by the Taiwanese audience, who gave it a standing ovation after the performance. It was a valuable experience that the Noh actors and the audience directly shared their emotions.

In the context of the accelerated digitalisation of recent years, Noh needs to change the relationship with its audience. Furthermore, in order for Noh to survive amidst the further development of tourism and globalism, it is necessary to convey the appeal of Noh not only to Japanese people but also to foreigners, and to have it recognised as an art form that should be handed down to the next generation. Based on my own experiences in Japan and abroad, I believe that we should not only use the Shinyo Kaikan as a base for organising events to connect with audiences face-to-face, but also make use of digital technology in the promotion and implementation of Noh performances to improve the viewing experience, and to facilitate further communication with audiences.

Moreover, it is also important to introduce Noh in school education. Although there are touring performances of Noh in schools as part of an initiative by the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ initiatives, the scope of these performances is limited. In cooperation with local schools, I would like to create opportunities for young people to experience Noh as much as possible, developing its future audiences.

By Alejandro Postigo

Every time someone asks me what Copla is, I struggle to answer. How can I describe in a few words an art form that is so nuanced, cultural, historical, social, and at the same time, so personal? Without being asked to, I feel compelled to take on the challenge of making people understand and appreciate the little gem that is Copla. This is why I have created Copla: A Spanish Cabaret, a project that’s not just a performance but a heartfelt exploration of identity, culture, and the timeless power of music. As a queer migrant artist, my work has always been deeply personal, and Copla: A Spanish Cabaret is no exception. This cabaret is about sharing a part of my heritage with audiences who may have never encountered it before. My hope is that by the end of the evening, you’ll not only understand Copla but also feel its emotional resonance, just as I do.

Why Copla matters: Copla is a genre of Spanish music that first captured my imagination because of its ability to express the raw, unfiltered emotions of those who felt they didn’t belong. Originating in the early 20th century, Copla became a lifeline for many during Franco’s dictatorship — a voice for the repressed , the exiled, and the forgotten. These songs told stories of longing, heartbreak, and resilience, and they were a way for people to hold on to their identities and memories in the face of oppression.

Growing up in Spain I was surrounded by these songs. They were in the background, a part of family gatherings and public celebrations but also a reminder of a painful past. Copla is deeply entwined with the experiences of my ancestors, who lived through dictatorship and displacement. When I moved to the United Kingdom, I found myself missing that connection to home, to the songs that spoke to my heart. That’s when I realised that Copla could be more than just a piece of my past—it could be a bridge to connect others to this rich, emotional tradition.

When I perform Copla, I’m not just singing. I’m reliving the stories of those who came before me and I’m sharing a part of myself with you.

The journey of Copla didn’t end with Spain’s transition to democracy. In fact, it found new life in the hands of drag artists who reimagined these songs as anthems of queer resistance. They took the drama, the intensity, and the defiance of Copla and used it to push back against societal norms, claiming a space for those whose voices had been marginalised. This transformation is what inspired me to bring Copla to a new international audience, to show that these songs are not relics of the past, but living, breathing expressions of what it means to be queer, to be in-between, to be a migrant.

When I perform Copla, I’m not just singing. I’m reliving the stories of those who came before me and I’m sharing a part of myself with you. My alter ego, La Gitana, embodies this journey. She’s fierce, she’s unapologetic, and she’s my way of honouring the resilience of queer migrants everywhere. Through La Gitana, I reinterpret Copla songs in English, breaking down linguistic barriers and inviting everyone, regardless of background, to connect with these powerful narratives.

I have been bringing Copla to British audiences since 2011, which has been both a challenge and a passion. As a migrant artist, it hasn’t always been easy to find the platforms and support needed to showcase this work. Often the theatre industry here can feel very Anglo-centric, and breaking through that can be tough. But every time I see someone in the audience moved by a song, every time a conversation starts because of a performance, it’s all worth it.

Copla: A Spanish Cabaret is a response to this challenge. It’s about creating a space where queer migrant voices can be heard, where stories that might otherwise be overlooked can take

centre stage. Through live music, narration, and audience interaction, the show explores identity, belonging, and the beauty of being in-between cultures. It’s an invitation to see the world through the eyes of those who don’t always fit neatly into one box or another.

I want to make you love Copla as much as I do. I want you to feel the passion, the pain, and the joy that these songs carry. I want you to see how they’ve shaped my own journey as a queer migrant artist and how they continue to resonate with the experiences of so many others. Copla isn’t just about nostalgia—it’s about connection, resilience, and the courage to be yourself no matter the odds.

So, I invite you to join me for Copla: A Spanish Cabaret. Whether you’re familiar with Copla or hearing it for the first time, I promise you a night of music, storytelling, and perhaps a little bit of magic. This isn’t just a performance—it’s a conversation, a shared experience and I would love to have you there.

I’ve started this journey because I believe so strongly in the power of Copla to connect us. But the journey doesn’t end here. I’m determined to keep bringing this project to more venues, to more audiences, because these stories deserve to be told and they deserve to be heard. Come and let’s explore Copla together. Let’s celebrate the voices that refuse to be silenced, the stories that bridge cultures, and the music that can make us feel a little less alone. I can’t wait to share this journey with you.

To find tour dates and more information about the Copla Cabaret , please visit www.thecoplamusical.com

By Alice Powell

I work as a film editor, primarily working in long form documentary film, but also working across other genres as well, such as fiction films and work for galleries. I try as much as possible to vary the types of projects I work on so that I am not typecast into just one style of filmmaking. As a result I’ve worked on a wide range of subjects from NASA astronauts, injured veterans at the Invictus Games and human trafficking in Nepal.

Through my experience, editing a documentary is a different challenge to working on fiction, as there is no script for the film.

That is not to say that the filmmakers don’t know what kind of story they want to tell, but it is my job, alongside the director and producers, to investigate every aspect of the narrative and find the best methodology to tell that story in the most impactful way to an audience. This often means reviewing hundreds of hours of material, all of which needs to be considered and then constructed into a concise, clear and compelling feature length film. Finding the balance between truthfully telling the story but doing it in the most engaging way possible is the tension that most documentaries are concerned with. We can never present every fact and every twist, especially in a feature doc, so we have to think very carefully about what to present that keeps an audience engaged and connected to the story whilst still remaining true to the spirit of the events. Working on stories that represent the lives of real people, rather than fictional characters, is a huge responsibility that I take very seriously, and I always keep this in mind when I work on my films.

I can’t give any details about the films I am currently working on but most recently I have been involved in a series

for Amazon Prime about the treble-winning Manchester United team from 1999.

I was responsible for one episode, episode 3, which dealt with the Champions League final. We used interviews with the players intercut with archive material from that time. I was particularly interested in the pressure the players were under when they had to perform on the largest stage imaginable, and we tried to use as much archive material as possible so that the audience could feel close to the action. To highlight how different my projects have been, the film before that was called Your Fat Friend and is a feature documentary about Aubrey Gordon, a writer from Portland, Oregon, who writes about her experience of being a fat woman in the world. The film follows her over a five year period during which time she goes from anonymous blogger to best selling author. The film mixes the political with the personal, quite literally, as we discuss the challenges faced by fat people–such as access to healthcare and travelling on a plane–but also Aubrey’s relationships with her family, through intimate observed scenes. What I am always looking for in a film is subjects with whom we can empathise and gain greater understanding.

I initially started as a filmmaker by chance when I was 15 years old, when I had chosen to do work experience at a local community cable television company.

(This was the late 90s and cable TV was quite innovative for its time.) They would only broadcast a few hours a day and made local news reports and features. I loved it so much. The people were very kind and very generous, they all showed me every aspect of what they did. It had never occurred to me that this was a job that I could pursue and it was seeing the team working creatively together that inspired me. I then joined a volunteer network at my local media arts centre, where I diligently attended every course they had going. All of this meant that by the time I had left school I had quite a range of experience working on amateur films in very junior roles. Following on from that I went to university to study Film, which was where I developed a love for editing. A year after graduation I was accepted to attend the National Film and Television school to study an MA in Film Editing.

I would not say that going to film school is a must, although for me it was a very important opportunity that helped me to gain confidence and join a network of filmmakers.

I also feel that this experience broadened my skills in storytelling, critical thinking, and how to present ideas. I think that anyone interested in filmmaking can go down this route. But if it doesn’t suit them, then I would recommend getting involved in as much work as possible, even if it means giving up some free time to do it. There are a lot of technical things that can be taught but experience of actually making work counts for a lot, as the best way to learn is to get it wrong, and then understand how to be better next time. Most people start off making quite boring, disappointing films, as filmmaking is very hard. But if that doesn’t put you off, and you are able to strive to become better, then that desire will certainly help you to become the filmmaker you want to be. Filmmaking is not about the equipment you use but about the stories you tell; consider why you are telling them and to what end. Also don’t be afraid to follow your instincts. Learn the rules first but then don’t be scared to break them.

By Iketina Danso

Broadening audience representation is often claimed to be a priority by organisations and institutions, with ambiguity around what this means. Without clear definitions, it can be difficult to see if changes in audiences or widened access to decision making within theatre institutions is taking place. Conversations about bringing in a broader diversity of theatre-goers are linked to conversations about diversity in theatre education , production, and audience experience, with concern about topics which have been made visible by mega talents such as Michaela Coel , who has spoken frankly about her experiences of racism and classism. Moreover, controversial initiatives like ‘Black Out Nights’, introduced to theatre as part of the highly acclaimed run of Slave Play at the Noel Coward Theatre, London, have raised the topic of how far we should go to broaden audience reach . Slave Play writer Jeremy O Harris , argues that ‘people have to be radically invited into a space to know that they belong there’.

Meanwhile, the epic BSL bilingual performance of Anthony and Cleopatra at the Globe Theatre, London set stellar standards for what is possible in terms of broadening audience inclusion and recognising diverse audience needs.

Broadening audiences to be more representative of communities that surround theatre buildings is an intersectional challenge that has the potential to create new and exciting experiences for everyone. It is also an endeavour of organisational, structural and practical change. This move towards change is not optional. In the competition for attention against social media, streaming and other services, theatres and theatre education spaces must do more to reflect the lives of those outside their doors in the development, production, and presentation of storytelling on stage. This requires performance spaces of all sizes to ask, ‘who is here, who is absent and what must we do differently so that our work is visible, accessible, and inclusive?’

The Vienna based association Hint Wien (highly intersectional Vienna), has developed a number of programmes together with arts institutions, and has learned lessons that are very relevant to the international theatre scene. Working with the arts education departments of several established arts institutions, Hint Wien developed arts education programmes for the public, aimed at attracting new audiences through highly intersectional and queer centred storytelling. In practice, Hint Wien introduced activities that turned public museum spaces into mutual learning and co-creation spaces. Rather than entering arts and cultural spaces, in order to consume and observe; visitors were actively sharing experiences and stories to contextualise the positioning of the works in their lives. Moreover, Hint Wien remains anchored in intersectional queer community events outside of formal arts and culture organisations through Queer Writers Circle Vienna. This includes performance nights Poetry for Pride during Pride month and ‘Poetic Intuition’, an international, highly intersectional queer storytelling festival. Both events bring together large public institutions and community organisations for performances, and peer-to-peer learning and creation, as sources of situated knowledge. These interactions centre voices that are often underrepresented or marginalised, by inviting them to co-create more inclusive narratives about the

works on display. The result is a significant increase in the diversity of visitors and audiences.

In order to reach broader audiences, it is necessary to continue to build spaces in theatres where co-creation is possible. Especially for those who are new to the theatre experience, and wherever the stories of marginalised groups are told; more spaces must be created to actively contribute to new rules of interaction and redefine and co-create in that space. It also helps to organise group visits by specific identities or specific organisations as seen for Slave Play.

Through its arts education work, Hint Wien has found that when it comes to broadening audience representation by growing more diverse and inclusive audiences, it is necessary to integrate activities into arts and culture programming that disturb the assumptions of what that audience looks like, and who holds storytelling expertise. We all have blind spots and so do theatres. The theatre and theatre/drama education sectors must look for ways to build genuine interactions with an increasingly diverse pool of visitors. There is a lot of flexibility in how to approach this challenge. This flexibility is an opportunity to overcome institutionalised blind spots. Strategies should aim to bring in the changing hopes, expectations, and inspirations present in the perspectives of unfamiliar audiences. In the long term, this will reinforce the argument for working with community groups, activists, human rights defenders, and changemakers. Moreover, the reality of limited budgets makes collaborative and interdisciplinary working worth exploring. Organisations would do well to look for ways to share knowhow and resources, in order to ensure that initiatives to broaden audience representation through active participation are adequately resourced.

In broadening audience representation, ticket buyers do not only want to be passive observers. They also want to redefine arts and culture spaces for audiences of the future.

For further information, please see: www.hint.wien

By Kayode Brown

nity development and the arts, Brown was shaped by his parents—his father, Toronto’s first reggae radio host and a local principal, and his mother, a trailblazing minister and professor. Growing up in Toronto’s vibrant hip hop and reggae scenes of the 1980s, Brown witnessed firsthand the transformative power of creativity. Yet he also saw how Black and Caribbean communities, particularly youth, were often left out of broader educational narratives. From this need, Just BGRAPHIC was born— not as a traditional arts programme but as a bold movement to revolutionise the way students learn and engage with the world.

The journey began with a modest after school programme at Westview Centennial Secondary School, offering dance and performing arts workshops. These early programmes provided students with a safe space for creative expression, allowing them to connect with their cultural heritage while building confidence and resilience. Dance became more than a form of movement; it became a powerful tool for developing leadership, teamwork, and emotional intelligence. What started as a single after school programme soon laid the foundation for Just BGRAPHIC’s broader vision: to use the arts as a means of empowering youth and challenging systemic barriers.

A key inspiration behind this vision was Do Dat Entertainment, a pioneering hip hop dance company from Toronto that rose to prominence in the 1990s.

Led by Luther Brown, Do Dat fused reggae rhythms with hip hop choreography, breaking racial barriers and establishing a new artistic identity for Black dancers in the city. Just as Do Dat challenged the limits imposed by the industry, Just BGRAPHIC aims to equip students with the tools to overcome similar barriers, both within the arts and beyond.

As Just BGRAPHIC grew, so did its offerings. The organisation now provides an extensive range of programmes, such as SYNC Music, where students learn to produce music not only for recording artists but also for films, television, and commercials. Sustainable Fashion and Custom Shoe Design introduce students to upcycling and cultural storytelling through fashion, combining creative expression with sustainability. These programmes go beyond technical training; they foster a mindset of cultural awareness, sustainability, and personal expression.

A significant part of Just BGRAPHIC’s success stems from its collective of artists and educators. This diverse group of professionals, with expertise in dance, visual arts, music, and digital media, brings a wealth of knowledge to the organisation. Together, they collaborate to deliver culturally relevant and impactful learning experiences that engage students in both creative and social growth. By centering students’ voices and stories, Just BGRAPHIC ensures that each participant is seen and heard in their educational journey.

The organisation’s recent expansion into Digital Arts and Media represents an exciting evolution, led by Bernard Mafei, Program Director for Digital Arts & Media. With over 15 years in Canada’s esports industry and a background as a top competitor, Bernard now serves as the Senior Administrator of Esports at Humber College and chairperson for postsecondary at Esport Canada. His extensive experience working with Epic Games to deliver professional development workshops in Unreal Engine, Twinmotion, and Fortnite Creative is helping to shape Just BGRAPHIC’s digital programmes. Through Bernard’s leadership, Just BGRAPHIC is now positioned to deliver cutting edge digital arts education, equipping students with career ready skills in esports, 3D design, and game development.

Today, Just BGRAPHIC’s impact extends far beyond its origins. The organisation has partnered with

institutions such as the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), Toronto Catholic District School Board (TCDSB), York Region District School Board (YRDSB), York Catholic District School Board (YCDSB), Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board (HWDSB), Dufferin-Peel District School Board, and Humber College. These collaborations enable Just BGRAPHIC to deliver Specialist High Skills Major certifications, professional development workshops, and immersive learning experiences to students and educators alike.

Despite its growth, the organisation’s core mission remains unchanged: To use art as a vehicle for social change, equity, and empowerment.

Looking ahead, Just BGRAPHIC is excited to embark on a new collaboration with ISTA (International Schools Theatre Association), a global leader in theatre education. Together they are working to integrate Just BGRAPHIC’s philosophy of culturally responsive arts education into International Baccalaureate (IB) programmes. This partnership will bring the essence of Just BGRAPHIC’s innovative approach to a global stage, where students in IB programmes can engage in creative, decolonised learning that reflects diverse voices and experiences.

Just BGRAPHIC is more than an arts education programme—it’s a movement. By integrating digital innovation, cultural storytelling, and social consciousness, Just BGRAPHIC empowers students to own their narratives and challenge oppressive systems. Under Kayode Brown’s leadership, and with the contributions of experts like Bernard Mafei and a dedicated collective of educators, Just BGRAPHIC is paving the way for a future where young people are not only creators but also change makers in their communities.

‘ P a in

At times I consider my work a living entity. It’s a trusted friend I can turn to for advice, a parent or guardian who can offer me solace, or a psychologist who knows exactly which questions to ask. I have always enjoyed writing, especially as a young boy, but I could’ve never imagined it would someday become my lifeline.

cre a t e . ’

could also be your world but

I was able

I studied at the Waterfront Theatre College in Cape Town from 2012-2015. As with many theatre schools, we had an open class or performance class as my college called it. This was a space where one could explore and experiment creatively once a week. You could do whatever you wanted! Dance, sing, perform a monologue, choreograph, play an instrument, show a short film you made.

It was in this class that I discovered my voice as a writer and the power that came with it. At first I used those Wednesday mornings to perform and direct the monologues I had written. After that came the movement pieces, the poems, the short films, and the songs with far too many unintended key changes. Procrastination was my (unintentional) superpower. I would book a slot to perform and forget that I had done so, which would lead to me sitting in an empty studio at 9:00pm the night before, stressing about what I would showcase the following day, and these were the moments where my creativity thrived. Once the spark was ignited, I could churn something out within an hour, all while experiencing a sense of euphoria as I submerged myself in my creative well.

It was only through the commentary of my lecturers that I realised I had been infusing elements of myself, and more specifically, my past, into these stories. These included traumas and regrets but also aspirations for the future. I wrote a piece about a homeless man and these extracts rang very close to home. Without realising it I was releasing years of pent up trauma (my father was homeless for the latter years of his life) through my writing, and that is where I discovered this internal flame that continues to glow. Years later, after being the victim of a racial attack, I turned to my pen. I wrote, along with a collaborator, a one-man show about the struggles of being a queer person of colour in modern day South Africa. I relived that night throughout the rehearsal process and a few nights on stage until it became a distant memory.

I was able to heal myself through my art, but more importantly, I could have a meaningful impact on audiences. The most valuable part of the theatrical experience is when audience members find me after the show and express the elements they related to or how the story has affected them. That is why I persisted. The industry was not always kind

to me but I continued to knock on doors, and where there weren’t doors, I built my own. But then the year 2020 came around and my flame was nearly extinguished. ‘Time to go knocking again’, I thought to myself.

My hammering brought me all the way to Hong Kong where I currently teach full time while still working on my creative endeavours; a difficult feat but worthwhile one. Before my current job I worked at a youth theatre production company, facilitating ECAs (extra-curricular activities) and producing professional productions. I was awarded the task of taking on one of the Bard’s most famous texts– the-one-you’re-not-supposed-say-aloud-ina-theatre-AKA-the-one-with-the-ambitious lady. And that ‘lady’ (how dare I, honestly) was my focal point. There have been a million and one interpretations of this text so it’s quite a daunting task to think about how I could breathe fresh air into those papers. But because I’m a little lazy and I don’t like pressure, I chose not to. I decided instead to dissect a character and look at an element that many consider to be the main theme of the play – ambition. Specifically, Lady Macbeth’s ambition. Where did it come from? Many teachers, theatre makers, historians and Tik Tok users have presented various answers to this question over the aeons. But I wanted to find my own answer (Google would inform me there are in fact many others who found my answer). Alas.

My source of inspiration for this utterly unique question came from the 5th album of American recording artist Halsey’s (she/they), ‘If I can’t have love, I want power’. I snapped my fingers and said, ‘YES!’ This is my angle. Very little is said about the Macbeths’ deceased child but we know they had one. Lady Macbeth was a childless woman in the 11th century, so one can only imagine the years of biting commentary she had to face. We meet a hardened woman who will do whatever it takes to reach the top but I chose to explore the mother who never stopped grieving her child.

So after Duncan’s death, I link Lady Macbeth’s escalating insanity to yearning for her child. Her mental descent is triggered by the guilt of the murder, of course, but it’s the beginning of her journey back to her young one. I did not want to make her death a tragic one.

Instead, it was a reunion with her child, and she left the stage smiling.

My main critique in my early years of performance class was that I focused too much on the story. I was determined to create twists and turns and create new dimensions wherever possible, infusing as many facets of theatre as possible and trying to build a unique world. But I forgot the most crucial aspect: The characters who have to inhabit these worlds. This changed towards the end of my training as I became more conscious of how my stories reflected parts of me. Through my understanding of my complexities, I realised my characters were as, if not in some cases, more complex than I was. I could actually use them to better understand myself and explore my own psychology.

My flame diminished during and after COVID-19. I struggled to reconnect with my art. I had stories but no characters. I was too distraught by the state of the world and my life crumbling before me even to dare look inward at all the boxes I had to unpack. But theatre would once again save me. Being presented with the opportunity to direct someone else’s characters reignited the flame. I was reminded of the joy of being a creator—the pleasure of analysing a character until it feels like you are their parent, best friend or even psychologist (and don’t worry, I have one of those now).

I was reminded the joy of being a creator of

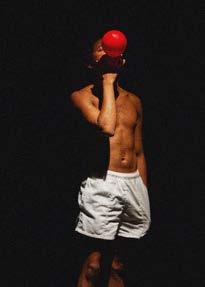

By Michael Growler

Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Hi, I’m Michael Graller–not a very show-bizzy name so in college I changed it to ‘Growler’. I’m 56 years old and married to Bill Bowers who is a brilliant performer and teacher. We have a 13 year old son named Max who is a martial artist, musician, and visual artist. Whenever we have the chance we take in all the culture that NYC has to offer and we love to travel.

What kind of work do you do and what are you currently working on?

I’m the costume shop supervisor at Playwrights Horizons in New York City. We’re an off-Broadway theatre company that is dedicated to developing new works and nurturing new talent. Over the last 52 years, Playwrights has produced many plays that are still being done all over the world, including the premieres of Sunday in the Park with George, Falsettos, Clybourne Park, A Strange Loop, Driving Miss Daisy and The Whale.

My job is to be involved in every step of production from the time the script is chosen through the closing of the show.

When Playwrights choose a play they hire the design team which includes a costume designer. I will work with the designer to be sure they have everything they need. I help with the budget and bookkeeping, hire the stitchers and craftspeople to make the costumes, do the fittings with the actors, and hire the dressers who maintain the clothes, and help the actors at every performance. Our season is just about to start so I’ll be taking measurements of all the new actors, and the shopping and creating will be underway.

What led you to your current role? In my 30 year career I have worked in every possible corner of the costume world. I’ve done theatre, film, television, fashion shows etc. I didn’t study theatre in school but looking back I can see that I was meant to work in Wardrobe. My memories of people are usually centred around their clothes and the colours that were present when we were together.

In my 20s I needed a job and my best friend belonged to a theatre company. She said their costume designer was looking for an assistant and the next day I was working. Of course I had no idea what I was meant to do–technical theatre jobs were not discussed at school, we didn’t know any theatre people, my parents had no show business connections or experience.

But it was such a natural fit. All I had to do was read the script and help decide what the characters would wear? That seemed like the easiest thing in the world! Now I know that it can be much more complicated than that. I didn’t know what dramaturgy was then–now I know it is essential to ask ‘why’, until there are no more why’s.

If it’s summer, ‘why would she wear a coat?’ (she has something to hide inside it). ‘Why is his suit so cheap if he has such a great job?’ (he has been lying about his debts). ‘Why are the shoes loud?’, ‘Why can’t he change his clothes quicker?’, ‘Why are we waiting for rehearsal to start?’ ‘Why am I so tired?!’

The man I was assisting was set on retiring and when he would get calls to design shows he would say, ‘I’m not available but my assistant is.’ Thanks to him I was designing shows steadily for a couple years and suddenly I had a call asking if I knew any dressers. I said I was a dresser and honestly, I didn’t know what that was. They also asked if I did wigs. I said I did–I lied.

I learned that the dresser is the person responsible for the costumes after the designer has designed them. I would get to the theatre hours before each show and clean the clothes, do any sewing repairs, make sure everything looked exactly the way the designer meant for them to look, and put all the pieces in the dressing rooms or backstage so they were ready to be worn during that performance. Being a dresser is so much fun—it’s social, noisy, fast paced. Everyone backstage really relies on each other and you’re all working toward the same goal.

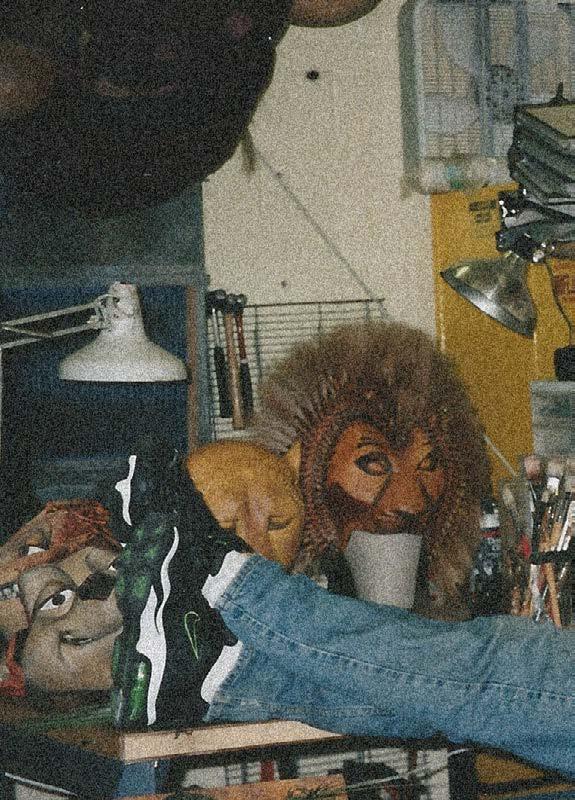

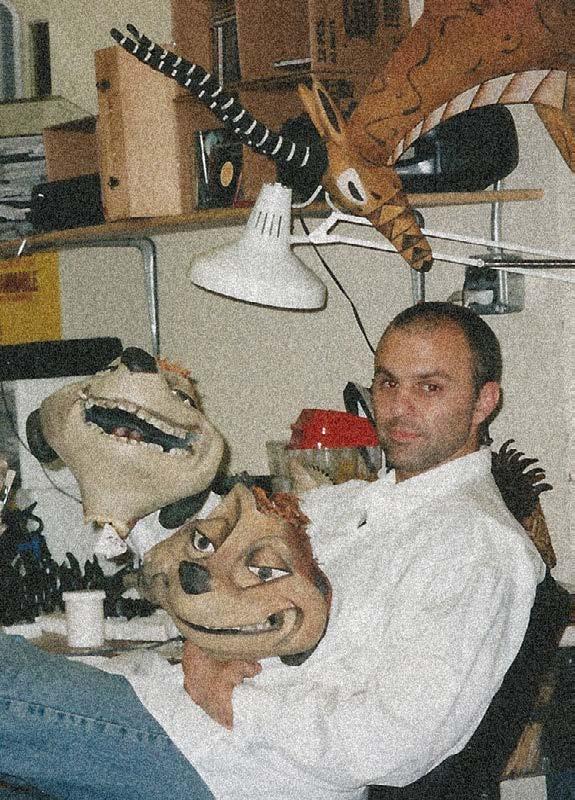

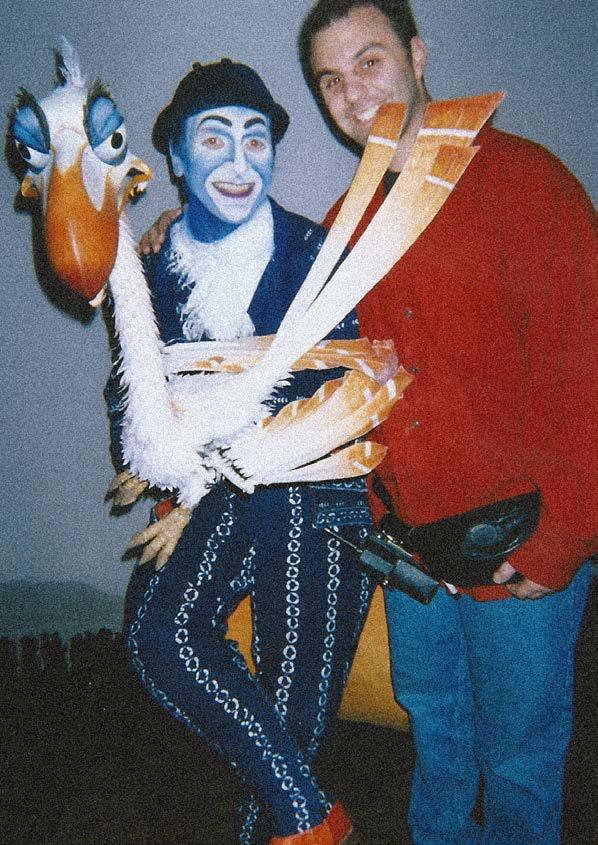

I was a dresser on Broadway for more than 30 shows over 20 years. My husband Bill and I met on The Scarlet Pimpernel and then we both worked at The Lion King. He was Zazu and I was the assistant wardrobe supervisor and I ran the puppet shop. My crew and I were charged with making sure all the puppets looked great and worked well. It was a massive undertaking. I was there for every performance and most days I’d get called to the stage to fix a broken zebra leg, Simba mask or Timon hand before they had to go back onstage. Sometimes in less than a minute!

After all those years and shows I felt I wanted a new challenge. Luckily, I was working on the play Rabbit Hole with Cynthia Nixon. She was about to make the first Sex and the City film and wondered if I’d like to be her dresser. I had no idea what that

entailed but she said all the technical things I would need to know I’d learn within a week and that the hours are so long that a lot of the job is finding people you’d actually like to spend 14 hours a day with. She was right. Working in costumes for film and television is gruelling. You work around 60-70 hours in the week. The money is very good because you are working tons of overtime hours but at a certain point you just want to sleeeeep.

The actual job is a little bit different from theatre. During one day on set you will only shoot about three pages of dialogue as opposed to being able to tell the entire story each night in the theatre. If a movie takes place in one day the actor might wear the same clothes every day for months. In that case we’ll have a couple sets in case they get worn down or stained or torn. Normally the actor has different costumes for different scenes but the scenes are shot out of order, so it is my job to take many pictures and notes to be sure the correct thing is worn in the correct order. It’s called continuity, and it is very bad if a character is wearing a blue shirt when they cross the room to open a door and a green one when they walk through to the next room.

After 10 years of film and television it was time to settle down. The incredibly long hours were definitely not possible with a growing family and another happy accident happened. I had an old friend who was working in theatre and called to see if I knew anyone who wanted to step in for the costume shop supervisor who had just quit and stormed out of rehearsal. ‘I’ll do it!,’ I said.

It is a very nice place to be creative and meet all kinds of theatre artists. I don’t have the pressure of making major design decisions, and I don’t have to be at the theatre every night and all weekend during performances.

What advice do you have for someone looking to pursue a career in costumes?

There are lots of routes you can take to work in Wardrobe. The best thing to do is to make yourself an expert at the thing you like best. I have a friend who has made a career of knitting custom sweaters for Broadway shows. Another friend likes to shop so she went to fashion school and now spends her days shopping for clothes that movie designers use on screen. If you like to embroider or sew or make puppets, become excellent at it. If you are very organised or have great computer skills or like to do admin, you would be an asset to any Wardrobe department. You can study fashion, costume design, textiles, millinery, theatre arts… you can do what I did, say ‘yes’ to opportunities that arise, and always be curious. You should never stop learning or growing.

Iketina Danso is a Diversity Equality/ Equity and Inclusion (DEI) expert and poet from London who is now based in Vienna.

Having worked in government, international policy, civil society and grass roots organisations and higher education; she has led initiatives in: intersectional gender mainstreaming, anti-discrimination and equality, organisational learning, human resources management and human rights. She now leads Diversity Equal Opportunities and Inclusion at the Vienna University of Applied Arts.

Iketina is founder and Chair of the association Hint Wien (Highly Intersectional Vienna) which empowers highly intersectional queer communities through authentic storytelling, and founder of Queer Writers Circle Vienna. Also known as poet JG Danso, she founded Verlag Triple Threat WOW in 2022 and has published two illustrated poetry books: A Thousand Ships (JG Danso, 2022) and A Thousand Ships Colouring Book (JG Danso, 2023) inspired by the legacy of queer icon Marsha P. Johnson.

Michael Growler’s 30+ year career has run the gamut of theatre making jobs.

He has designed costumes on and off Broadway and assisted such designers as Patricia Zipprodt and Tom Broecker. As a Wardrobe Supervisor on Broadway he worked with designers Bob Mackie, Jane Greenwood and Jess Goldstien and actors Martin Short, Liza Minnelli and Anthony Mackie.

In theatre, film and television he has been personal dresser to Laura Linney, Cynthia Nixon, Jeremy Irons, Billy Crudup and Kristen Wiig.

Growler has designed sets, assisted directors, and styled photo shoots with Richard Avedon and Arthur Elgort.

Some career highlights include being the Puppet Shop Supervisor at the Lion King and meeting his husband of 27 years, Bill Bowers, at The Scarlet Pimpernel.

He currently lives in New York City’s East Village with Bill, son Max and canine sisters Opal and Pearl.

London based film editor working across drama, documentary and everything in between...

Since graduating from the National Film and Television School in 2007, Alice Powell has acquired experience in both documentary and fiction films, which have been screened at various film festivals internationally, including Sheffield Doc/Fest, South by Southwest, Hot Docs International Documentary Film Festival, the Berlin International Film Festival, and the Tribeca Film Festival. She also has experience editing broadcast television programs and commercials. Alice emphasizes collaboration with producers and directors as a film editor to tell stories with integrity and a delicate human touch.

Alejandro Postigo is Senior Lecturer in Musical Theatre at the London College of Music, University of West London.

His PhD (2019) explored the intercultural adaptation of Spanish Copla songs as demonstrated in The Copla Musical and The Copla Cabaret (2014-24), seen in Europe and America. Alejandro’s research explores historical revisionism of Spanish musical theatre, and applies translation, queer and intercultural theories to his professional practice as a theatre maker. Recent research has led him to address the cultural and linguistic barriers found in Anglophone theatre contexts, and to champion the artistic contributions of non-native English speakers and audible minorities, as demonstrated in his latest show Miss Brexit (2022-24).

Paula Garfield is the Artistic Director of Deafinitely Theatre.

An actor, director and field creative leader, Paula has worked on a variety of television, film and theatre projects over the past twenty years. In 2002, she established Deafinitely Theatre with Steven Webb and Kate Furby. Paula has produced and directed many plays and worked extensively in TV, including Channel Four’s Learn Sign Language, Four Fingers and a Thumb, BBC’s Hands Up and Casualty, plus appearances in every series of the BBC’s deaf drama, Switch. Paula’s 2017 production of Contractions for Deafinitely Theatre won The Off West End Theatre Award (Offie) for ‘Best Production’, and her production of 4.48 Psychosis at New Diorama Theatre in 2019 was shortlisted for Best Director by Broadway World UK. Paula was also awarded the Tonic Award for her work at Deafinitely Theatre. Paula is now working on a new production ‘Barrier(s) written by Eloise Pennycott. Barrier(s) will go on national touring in Autumn 2025.

Terence Makapan was born in Cape Town, South Africa, where he studied at the Waterfront Theatre College, majoring in drama and musical theatre.

He started out as a freelance theatre maker for several years, writing most of his productions, before trying his hand out at film. The writing process has always been a cathartic experience for him, and that is where his true passion lies. Terence currently teaches public speaking in Hong Kong, while still working on his creative endeavours.

Kayode Brown is the driving force behind Just BGRAPHIC, a forward-thinking organisation dedicated to shaking up arts education.

With more than 15 years of experience as a digital artist, Kayode brings a unique mix of creativity and practicality to his work. He founded Just BGRAPHIC to give young people access to culturally relevant arts education that doesn’t just tick boxes but truly inspires them. The organisation’s programs go beyond the classroom, offering students real-world experiences, career guidance, and hands-on learning that aligns with Ministry of Education standards. Under Kayode’s leadership, Just BGRAPHIC has become a space where students can explore their artistic potential and find their voice. Currently pursuing his Master’s in Education at York University, Kayode is focused on creating inclusive, progressive education models that address systemic issues like racism and inequality. He’s committed to making sure that educators have the tools they need to teach in ways that empower all students. Kayode’s journey is all about breaking boundaries and challenging the status quo.

Kate Matzopoulos worked as a theatre teacher at Windhoek International School for the past 8 years and has recently started her PhD (full-time) in Education at the University of Bath. She works together with co-researchers in Nhoma. They are working towards creating a decolonised curriculum for their school in Nhoma.

Kanako Wakebayashi is an art manager of Japanese traditional theatre, Noh.

In her childhood, she performed on stage as a child Noh actor under the guidance of Michiharu Wakebayashi, her father and a Noh actor. She holds a BA in Western art history from Kyoto University and an MA in arts management from Goldsmiths, University of London. Based in an art complex Shinyo Kaikan, she currently organises and manages Noh performances and workshops to develop its audience in Japan and abroad. In March 2023, she organised Noh workshops in Japan House London and SOAS, University of London, attended by more than 160 people. Shinyo Kaikan

SCENE is produced by ISTA.

ISTA brings together young people, artists and educators from around the world to experience, create and learn through theatre and the arts .

ISTA provides transformational experiences through its membership, events, services, resources and professional development for students and educators working across the arts.

ISTA Lakeside Offices, The Old Cattle Market, Coronation Park, Helston, Cornwall TR13 0SR

United Kingdom www.ista.co.uk

Design: Alina Neukirch