84 minute read

Endocrinology Focus: Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism: A Reminder of the Often Forgotten Intricacies

Very little has changed with regard to the treatment of primary hypothyroidism since the introduction of levothyroxine sixty years ago. It is safe, effective and relatively cheap. For all these reasons, both condition and treatment often drop to the bottom of priority lists in terms of patient and medication review, which, much of the time, is reasonable and justified. However, when a drug acquires this ‘reputation’, there is a danger that important details become slowly diluted until in some instances they are forgotten about altogether. The fact is, there are some quite unique and critical points to levothyroxine treatment, which, if ignored, can result in suboptimal therapy and patient harm. Indeed research shows a third of patients are inadequately treated.1 Considering the burden of hypothyroidism with respect to associated comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, decreased quality of life and economic impact of same, a third of patients inadequately treated is significant. This article aims to highlight the salient points associated with hypothyroidism and levothyroxine therapy.

Background

The thyroid produces two major hormones; Thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) in approximately a 4:1 ratio with most T4 subsequently being converted to T3 in the blood. Release of these hormones is triggered by Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) from the pituitary gland, which itself is triggered by Thyrotropin Releasing Hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus. Initial diagnosis of hypothyroidism is usually on the basis of an elevated TSH level combined with a low free thyroxine level (FT4). Accurate prevalence figures for hypothyroidism in Ireland are difficult to come by and largely unknown. Partly due to the fact that there is likely a large proportion of undiagnosed cases given the general and vague symptoms associated with the condition, which in some case can be mild, or even absent or silent and not trigger much concern (fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, dry skin hyperlipidaemia). Globally it is generally accepted that up to 5% of the population are affected, with as many again undiagnosed. Worldwide, iodine deficiency is the most common cause of hypothyroidism (iodine being essential for thyroid hormone production in the thyroid gland). However, in areas of iodine sufficiency, 95% of cases are autoimmune in nature (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis). Secondary and tertiary disease (insufficient production of thyroid stimulating hormone/thyroid releasing hormone from the pituitary/hypothalamus) are less common.

The mainstay of treatment for hypothyroidism is thyroid hormone replacement with levothyroxine (synthetic T4) and treatment tends to be lifelong. Levothyroxine is the second most commonly prescribed medication in the US and is considered an ‘essential medicine for basic healthcare’ by the WHO.1 Synthetic T3 also exists in the form of liothyronine which has a much shorter halflife. However it is unlicensed in Ireland and although it may potentially play a role in specialist situations such as myxoedema coma (severe hypothyroidism and medical emergency) or as a trial in combination with levothyroxine when symptoms have not ceased,2 NICE guidance does not recommend a routine role for liothyronine.3

Initiation of therapy

For otherwise healthy patients under 50, levothyroxine is initiated at a dose of 50-100µg (taken on an empty stomach, half an hour before breakfast) and titrated until TSH falls to within desired range and symptomatic improvement is achieved. Most maintenance doses fall between 75-150µg/day with a maximum of 200µg. Due to the long half-life of levothyroxine (6-7 days), TSH should not be measured until 4-6 weeks after initiation, as it can take this long for levels to return to normal. Similarly, dose titration should be done in 4 week intervals and 50 µg increments. In patients over the age of 50 and/ or those with cardiac disease, an initial dose of 25-50µg/ day is recommended (or 50 µg on alternate days in the case of cardiac disease) with 25 µg titration increments every 4 weeks. Overtreatment with levothyroxine can induce or exacerbate cardiovascular disorders, including atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, atherosclerotic vascular disease, dyslipidaemia, and heart failure. In fact, low circulating thyroid hormone levels may be providing a protective effect for the heart, hence caution is advised when aiming to increase levels.

Factors affecting dose requirements

Levothyroxine is a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug, however dose control often doesn’t receive the same attention compared to other NTI-drugs such as digoxin and warfarin. An understanding of the factors affecting plasma concentrations of the drug and/or endogenous thyroid hormone are required in order to find and maintain the optimal dose for a patient and avoid therapeutic failure or adverse drugs reactions. Maintenance doses in excess of 150 µg are not commonly required, therefore other factors such as medication adherence, malabsorption, concomitant medications and comorbidities should be examined in patients not achieving adequate control in the 75-150 µg range. Several commonly taken medications, including over the counter products can impair the absorption of levothyroxine including iron and calcium supplements, aluminium hydroxide (found in many antacids), and some proton pump inhibitors. A gap of 4-5 hours should be observed between taking these medications and levothyroxine. Inadequate treatment of existing hypothyroidism during pregnancy can be detrimental given the importance of these hormones to the baby’s development. Levothyroxine is generally continued therefore, however thyroid hormone requirements increase during pregnancy due to increased oestrogen levels. This means levothyroxine doses will often have to be increased during pregnancy. TSH levels should be monitored closely during each trimester and doses titrated accordingly.

Written by Dr Shane Cullinan, Lecturer in Pharmacy Practice Royal College of Surgeons Ireland

When symptoms of hypothyroidism are not subsiding despite an increasing dose of levothyroxine and TSH levels returning to normal, consideration should be given to other potential causes such as hypoadrenalism and anaemia which often accompany hypothyroidism and result in similar symptoms.

Amiodarone

Amiodarone can be a particularly problematic drug when it comes to interpreting thyroid function and dosing of levothyroxine as it can induce both hypo- and hyperthyroidism. The molecular structure of the drug contains two atoms of iodine. A standard 200mg/day regime of amiodarone can result in 20-40 times the recommended daily dose of iodine. Given that iodine is a principle substrate for the synthesis of thyroid hormones, this in turn can lead to elevated levels of thyroid hormone. This is rare however as the body normally initialises a protective mechanism against this called the Wolff-Chaikoff effect whereby excessive iodine levels inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis. However, when the body fails to ‘escape’ from the WolffChaikoff effect, a phenomenon more commonly seen in patients with pre-existing autoimmune thyroiditis, this in turn leads to amiodarone induced thyroiditis

Conclusion

Although a simple and effective treatment for hypothyroidism, levothyroxine therapy is not without its complications and warrants attention, particularly at the beginning of therapy.

(AIH). Furthermore, amiodarone exhibits some intrinsic properties which compound this such as inhibition of conversion of T4 to T3 in peripheral tissues. Importantly, the half-life of amiodarone can be up to 100 days, meaning that it can have adverse effects on thyroid function even months after cessation which must be taken into account when monitoring a patient on levothyroxine and titrating doses.4

News

Subclinical debate

Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, defined as elevated TSH, normal FT4 and very mild or no symptoms, has long been a matter of debate. The benefits are not well proven, though thought to perhaps prevent progression to overt hypothyroidism, and these must be weighed against the potential risks including cardiovascular side effects. Indeed, some evidence suggests subclinical hypothyroidism, in the absence of overt symptoms, is actually associated with longevity in older patients. NICE guidance recommends treating with a TSH of 10 mlU/litre or higher on 2 separate occasions 3 months apart (with symptoms in those aged over 65).3 Given the lack of data, several sources recommend basing the decision on whether to treat or not on individual circumstances. 1. Chiovato L, Magri F, Carlé A.

Hypothyroidism in Context:

Where We've Been and

Where We're Going. Adv Ther. 2019 Sep;36(Suppl 2):47-58. doi: 10.1007/s12325-01901080-8. Epub 2019 Sep 4.

PMID: 31485975; PMCID:

PMC6822815.

2. Leese, G.P. Nice guideline on thyroid disease: where does it take us with liothyronine?.

Thyroid Res 13, 7 (2020). https:// doi.org/10.1186/s13044-02000081-y

3. NICE guideline (NG 145).

Thyroid disease: assessment and management. https://www. nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/ evidence/e-management-ofhypothyroidism-pdf-6967421681

4. Narayana SK, Woods DR,

Boos CJ. Management of amiodarone-related thyroid problems. Ther

Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jun;2(3):115-26. doi: 10.1177/2042018811398516.

PMID: 23148177; PMCID:

PMC3474631.

Inaugural European Hormone Day

On 23 May 2022 it was European Hormone Day. On this occasion The European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) published “Milano Declaration 2022: Recognising the Key Role of Hormones in European Health” which summarises the key messages of the ESE White Paper published in May 2021, and calls on national and European policy makers to better address hormone health in current and future public health policies and research funding programmes. With the support of nine dedicated Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from different countries and political affiliations, and the overwhelming engagement of our own endocrine community – with more than 60 endocrine societies and organisations also giving their endorsements - the Milano Declaration and European Hormone Day created a strong impact in its inaugural year. Many national endocrine societies also translated the materials and animations, and they are available in the Toolkit for use on www. europeanhormoneday.org to help the endocrine community to explain the role of hormones and why they matter. With over 1200 tweets during the 12 hours of Monday 23 May achieving 4.33 million impressions, the activities around European Hormone Day at ECE and across Europe gained a lot of attention – the conversation continues still on Twitter! National media also picked up the story and ran it online and in print. A large focus of the online engagement was around the activities on the European Hormone Day booth at the ECE Congress which actively promoted the Milano Declaration as well as European Hormone Day through lapel pins and photos in selfie frames that people could use to express their support for this new European Health Day. The engagement from the endocrine community at our annual congress was huge – and we hope that we saw you there taking your photo! “We are still in the process of evaluating the overall impact of the campaign, but we are confident that we managed to make our voice heard and helped to secure better policies and more research funding for our community. Please send us your comments and feedback on the 2022 European Hormone Day so we can collectively have an even stronger voice in future European Hormone Days,” said the organisation.

DIABETES IN PREGNANCY The role of the multidisciplinary team in supporting women and babies

Diabetes and Pregnancy team, National Maternity Hospital

Written by David Fitzgerald, Mary Higgins, Ciara Coveney, Catherine Chambers and Recie Davern

Introduction

Diabetes is the most common significant medical condition to affect pregnant women, and it is important that women can avail of the best quality multidisciplinary team (MDT) care to support them prior to conception, during the pregnancy, labour and birth, and in the postnatal period as they adjust to new parenthood. This article has been written by some members of the National Maternity Hospital Diabetes and Pregnancy multidisciplinary team. Our ethos is simple: that women with diabetes are the experts by experience, and we are the experts by knowledge (and still learning) but that by working together we can share important decisions and provide respectful care. While the article focuses mostly on care provided to women with preexisting diabetes (including, Type 1 diabetes (T1DM), type 2 diabetes (T2DM), mature onset diabetes of the young (MODY) or cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD), amongst others) the principles can also be generally extrapolated to Gestational Diabetes (GDM), that is diabetes diagnosed in pregnancy, resolving after the birth but conferring an increased risk of diabetes in the future.

We have selected five specialities to write in this article, but it should be highlighted that other clinical staff may play important roles depending on the background and needs of the woman. The input of general practice, nephrology, medical social work, psychology, psychiatry, ophthalmology, lactation consultants, neurology, intensive care, anaesthesiology and numerous other clinical and non-clinical specialists have been invaluable. The woman herself, her partner and family remain in the centre of this care, with all input individualised to their circumstances and needs.

Midwifery

Midwives recognise pregnancy, labour, birth and the post-natal period as a healthy and profound experience in women’s lives. The ethos of midwifery care is to work in partnership with women. Midwives who care for women with diabetes in pregnancy are specialist trained in both midwifery and diabetes care. Specialist diabetes midwives utilise their midwifery and diabetes expertise to act as an advocate for a pregnant woman from the preconception period right through to six weeks postnatal. Specialist diabetes midwives undertake a comprehensive patient assessment including physical, psychological and social elements of care using evidencebased practice. They also coordinate assessment, planning, implementation, monitoring and re-evaluation of clinical assisted and specialised care pathways for women within multidisciplinary teams for thosewho are deemed to fall within a ‘high risk’ category. Assessment of care takes in to account multiple factors including assessing pre-existing conditions, current glycaemic targets and recommending/starting pharmacolgical therapy for women with diabetes in pregnancy. They support women to achieve optimum blood glucose levels for both maternal and fetal interest.

With the evolution of diabetes technology including continuous glucose monitoring and subcutaneous insulin pump therapy, specialist diabetes midwives have upskilled to be able to read complex glucose algorithms and recommend changes to therapeutic agents as a result. Education and health promotion for women and their families are a cornerstone practice in midwifery to improve both short and longterm outcomes for mother and their infants. This includes the advent of initiatives such as antenatal expression of colostrum to educate and prepare women for their breastfeeding journey. Specialist diabetes midwives provide most of the inpatient diabetes care for complex diabetes, supported by the wider MDT. All inpatients are seen by a member of the midwifery team to review glycaemic control and recommend changes to pharmacological treatments. Some specialist diabetes midwives also have a prescribing qualification and prescribe diabetes agents/ consumables to both inpatients and outpatients. They discuss the management of blood glucose levels and pharmacological agents in the intrapartum period to ensure each woman feels in control of their diabetes for the birth of their baby. Women are reviewed frequently in the postnatal period to assess for hypoglycaemia and the physiological changes that the postpartum period can bring. Typically, we see a reduction in insulin requirements in the immediate postpartum period, often requiring a similar dose of insulin to the that of the prepregnancy period. They link with each woman weekly in the six weeks postnatal period and see them with their MDT visit before referring them back to their general diabetes service.

Dietitian

The role of the CORU registered dietitian on this dynamic team is to assess, diagnose and treat dietary and nutritional problems in a woman-centred and evidencebased approach. The dietitian who specialises in diabetes works collaboratively with the multidisciplinary team to provide an individualised dietary care plan for the duration of the woman’s pregnancy and for the first six weeks postnatally. Nutrition at the time of conception and during pregnancy has an impact on the immediate and long-term health of both mother and infant. Optimal maternal nutrition will give the infant the best start in life. Using behavioural change skills and empathy the dietitian focuses on supporting women to make positive lifestyle changes while being mindful of social factors and the limitations to change. Women need clear and consistent guidance on the foods to avoid during pregnancy to reduce illness due to exposure to foodborne toxins and pathogens. The dietitian meets the woman within the first week of booking with the hospital and will review the women regularly during her pregnancy. A comprehensive nutritional assessment will include Mary Higgins, Obstetrician, Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Ciara Coveney, Advanced Midwife Practitioner, Diabetes

Catherine Chambers, Senior Dietitian

Recie Davern, Endocrinology Fellow

a detailed history along with a review of relevant comorbidities such as Cystic Fibrosis, coeliac disease, renal disease, mental health issues, anaemia, irritable bowel syndrome etc. The nutrients from foods eaten provide the body with protein, fat, carbohydrate, vitamins, and minerals. There are different requirements for different nutrients to support pregnancy and the growing infant. Carbohydrate is the nutrient that causes a rise in blood glucose levels. The cornerstone of the nutritional management of those managing diabetes during pregnancy is to educate women on how to spread their intake of carbohydrate throughout the day in a consistent way and to choose higher fibre/ lower carbohydrate foods that are slowly released within the body. The dietitian provides update sessions on carbohydrate counting – accurate carbohydrate counting enables the endocrinology team to better determine insulin doses. Education is now provided in oneto-one and joint sessions, phone consultations and video sessions.

Use of insulin pumps (CSII) and/ or continuous glucose monitors during pregnancy is growing; these technological supports are helpful in optimising glucose control. The dietitian supports women to interpret the data particularly in understanding the effect food choices have on glucose levels. The dietitian supports women who are admitted to hospital during their pregnancy and at the time of the delivery. Use of the specific menu created by the catering department for those with diabetes is explained. Breastfeeding is encouraged and specific dietary advice is provided to ensure nutritional needs are met at that time. Other nutritional issues that arise during pregnancy may be nausea and vomiting, constipation, weight gain concerns, anaemia, patterns of hypoglycaemia, mental health issues or culturally relevant food choices.

Supporting women who are managing diabetes during pregnancy is very rewarding. The dietitian will coordinate and link with dietitians in the community and tertiary hospital diabetes centres both before and after pregnancy.

Endocrinologist

The Endocrinologist is a medical doctor who specialises in the management of all forms of diabetes both during and outside of pregnancy. Our role begins in the preconception planning stage of a woman’s pregnancy journey. Many women with pre-existing diabetes may be on agents that are not recommended in the first trimester of pregnancy. We routinely counsel women of reproductive age in our general diabetes clinics to attend a pre pregnancy clinic prior to any plans for conception. In these clinics we start women on the higher 5mg dose of folic acid, transition off any teratogenic agents, ensure the management of any diabetic complications are optimised and aim to tighten glycaemic control to reach the optimum HbA1c levels. During pregnancy, we will meet with women early in their antenatal course. At this visit we enquire about their history of diabetes. We will ascertain the length of diagnosis; the presence of any diabetic complications and we assess women’s hypoglycaemic awareness. In Dublin we can arrange for referral to the Mater Miscericordiae University Hospital ophthalmology team who specialise in retinal screening in pregnancy as more regular screening is required during pregnancy. We also screen for other conditions that can be more common in women with pre-existing diabetes such as thyroid dysfunction. Women receiving a wide range of anti-glycaemic therapies attend our clinic – continued subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), multi daily injections (MDIs) or oral agents. We have experience in using all these different therapies in pregnancy as well as continuous glucose monitors (CGM), though we do recommend the use of some finger prick blood glucose testing during pregnancy to help get the most accurate data. A lot of women find that the placental hormones during pregnancy can make their diabetes difficult to manage and the Endocrinologist, along with the remainder of the multi- disciplinary team (MDT), are here to help women with any challenges they encounter. The blood glucose targets in pregnancy are also different to those outside of pregnancy and can take time to become familiar with. We review women every few weeks initially, but we also invite women to submit their blood glucose readings weekly, via email or telephone, for the endocrinology team to review. This helps us to support women during their pregnancy and allows us to work together to solve any issues that may arise. At the time of birth, we can arrange a blood glucose management regime to suit whichever mode of delivery that the women and our obstetric colleague’s plan. We devise an insulin regime to manage blood glucose levels during the delivery to ensure stability to help reduce the chance of neonatal hypoglycaemia after birth. We will continue to support and work with women for the 6 weeks postpartum before arranging to transfer their diabetes care back to the practitioner who assisted with their diabetes prior to pregnancy.

Obstetrics

The obstetrician, a medical doctor specialising in pregnancy and postnatal care, may be the lead named clinician within the multidisciplinary team, but remains very much one of a specialised group. Women with pre-existing diabetes are usually booked for early antenatal care, often attending at five- or six-weeks pregnancy. The first role of the obstetrician is often to confirm the viability of the pregnancy. Early ultrasound can be affirming (a viable heartbeat), surprising (twins or triplets!) or devastating (miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy). Since the 2018 referendum we also acknowledge that some women with diabetes may not wish to continue their pregnancy or may be diagnosed with a fetal abnormality and therefore termination of pregnancy may be requested. Whether the news is good or not, compassionate kind care is vital.

One of the most common complications of early pregnancy is nausea, vomiting or hyperemesis. Ultrasound to out rule an obstetric cause (multiple or molar pregnancy), linking with dietetics and offering the options

Diabetes in pregnancy Midwifery Team - Left to Right - Ellie Ahern, Ciara Coveney, Eimear Rutter and Hannah Rooney

Pharmacy Team, Left to Right Linda Simpson, David Fitzgerald, Aine Toher, Louise Delany and Montse Corderroura

of medications are standard management, when available. Women with diabetes often attend regularly throughout pregnancy, and regular reviews assuring them that the baby is growing and appears to be developing normally is reassuring. The routine anatomy scan at 18-21 weeks’ gestation is often supplemented with a fetal heart scan (echocardiography) due to the increased risk of fetal cardiac abnormalities with maternal diabetes. Regular assessment of fetal growth is important; this is done by both measurement of the symphysiofundal height of the maternal abdomen, measuring the liquor volume around the baby and measuring fetal skeletal and abdominal growth by ultrasound. The decision of mode and timing of birth is individualised to the women, her baby and her circumstances. Generally, the advice is that the baby should be born before the woman’s estimated due date, but how soon before will vary. Women with diabetes can, and do, deliver vaginally, but it is recognised that there is a higher rate of caesarean birth. This may be due to an increased rate of induction, bigger babies, maternal request or complications in labour. One of the most feared complications is that of shoulder dystocia – that the baby’s head will be born but that the shoulders are caught behind the maternal pelvic bones. While every clinician working on the labour ward is trained for their role should there be a shoulder dystocia, prevention is better than treatment. However, this is complicated by the fact that over half of all shoulder dystocia emergencies occur in normally grown babies. Postnatally women are monitored for complications of birth, including postpartum bleeding, infection and deep venous thrombosis. The psychological process of transition to parenthood should not be underestimated, and in some women further help may be required if they develop postnatal depression or psychosis.

Pharmacist

Clinical pharmacists can play a vital role on the MDT, contributing to the management of obstetric patients with pre-existing diabetes through utilising their knowledge of pharmacotherapy and experience in medication management. This role often begins at the stage of pre-conception planning, where pharmacists collaborate with the clinicians providing obstetric care to provide detailed counselling to patients. The importance of planning a pregnancy is emphasised with patients being advised to use contraception until they have achieved good blood glucose control. At this stage, pharmacists can contribute to a review of blood glucose targets, glucose monitoring, insulin regimens, and other medications for treating diabetes or its complications. Women with diabetes may be advised to use metformin as an adjunct to insulin in the preconception period and to stop all other oral blood glucoselowering agents. Patients who are taking statins, angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-II receptor antagonists are advised to discontinue these medications due to the potential for embryo-toxicity or adverse pregnancy outcomes. Advise is given to take folic acid 5mg per day until 12 weeks’ gestation to reduce the risk of neural tube defects.

During pregnancy, good maternal glycaemic control is vital to reduce teratogenicity, but needs to be balanced against the risk of hypoglycaemic episodes which are associated with significant maternal and fetal risks and can occur more frequently due to impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia in pregnancy. Pharmacists can contribute medication expertise in making pharmacotherapeutic decisions on appropriate choice ofinsulins regimens and in providing education for patients so that they may self-manage their blood glucose levels. Pregnant women with insulin-treated diabetes will be advised to always have a fastacting form of glucose available such as glucose-containing drinks or dextrose tablets. Available evidence on the rapid-acting insulin analogues (aspart and lispro) and the long-acting isophane insulin, does not show adverse effects on pregnancy or the health of the baby, and as such they are the first line choices for insulin regimens during pregnancy. Consideration can be given to continuing treatment with longacting insulin analogues such as detemir or glargine for patients who have established good blood glucose control with these agents before pregnancy. During an inpatient admission, an essential role of the pharmacist as part of the MDT providing care for obstetric patients with pre-existing diabetes is to ensure that the patient fully understands their insulin regimen, or changes to it, has sufficient supply of insulin and most importantly that their regimen is prescribed on the drug chart and clinicians taking care of the patient are fully aware of their more complex needs. The process of medication history taking, and medicines reconciliation is of particular importance around the time labour where blood glucose levels and insulin doses must be tightly managed. Of note is the need to give additional doses of insulin according to an agreed protocol for women with insulin-treated diabetes at risk of preterm labour and who are being administered corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation. Pharmacists play a role in the postnatal period, advising patients to reduce their insulin dose immediately after birth and providing advice on the use of oral blood glucose-lowering therapy while breastfeeding.

Conclusion

We have described some aspects of our role in providing care to women with diabetes as part of a multidisciplinary team. Another core principle of our care is communication. It is incredibly satisfying when a problem in providing care is solved by a clinician’s expertise or knowledge, no matter what their speciality. It is for this reason that all of us would say that we have learned so much about the value of multidisciplinary care from our colleagues. In addition, the expertise and knowledge of women and their families have taught us a great deal about shared decision making and the importance of keeping women and babies in the centre of the care that we provide. This article is dedicated to the women and babies we care for, with the immense privilege that it is to do so.

Can Weight Loss Improve the Cardiovascular Outcomes of Patients with Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea?

Written by by Ayyad Alruwaily1, Heshma Alruwaili1, John Garvey2 and Carel W. le Roux1,3,* 1Diabetes Complications Research Centre, Conway Institute, University College Dublin, D04 V1W8 Dublin, Ireland 2Department of Respiratory Medicine, St Vincent’s University Hospital, D04 T6F Dublin, Ireland 3Diabetes Research Group, School of Biomedical Sciences, Ulster University, BT52 1SA Coleraine, Ireland

Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repetitive upper airway collapse during sleep resulting in a temporary cessation of breathing (apnea), shallow breathing (hypopnea), or respiratory-related arousals. The apnea–hypopnea index measures the number of apnea and hypopnea events per hour of sleep. The apnea–hypopnea index is used to further classify obstructive sleep apnea as mild (5 ≤ apnea–hypopnea index < 15), moderate (15 ≤ apnea–hypopnea index < 30), or severe (apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 30).1 The pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea is commonly believed to be primarily due to anatomical anomalies of the upper airway. While a defect in the upper airway anatomy is common, it is not the only pathogenic process at work. Anatomical and non-anatomical elements have been included in a novel model of obstructive sleep apnea pathogenesis. These non-anatomical aspects include (1) impairments in the upper airway dilator muscle function during sleep, (2) respiratory control instability, and (3) low respiratory arousal threshold.2

Obstructive sleep apnea has a global prevalence of 13-33% in middle-aged men and 6-19% in middle-aged women.3 The rising prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the recent decades has been linked to increasing rates of obesity.4 Obstructive sleep apnea has been linked with many different cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, stroke, heart failure, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation.5,6 Adults with obstructive sleep apnea, in addition to increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, also have worse cardiovascular outcomes.7 We reviewed the associations between obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease and whether weight loss may improve the cardiovascular outcomes of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Increases the Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease

Among the mechanisms which explain the association between obstructive sleep apnea and myocardial infarction (MI), common risk factors include male sex, age, hypertension, obesity, and smoking.8 However, other direct effects of obstructive sleep apnea merit consideration. The combination of repetitive apnea–hypopnea, hypoxia, and arousal from sleep increases sympathetic activity, which is maintained during wakefulness, thus increasing myocardial oxygen demand.9 The mechanistic understanding which connects obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease is poorly understood due to the diverse and complicated elements of obstructive sleep apnea and the multiple other comorbid conditions (especially obesity) impacting cardiovascular health. When obstructive apnea or hypopnea occurs, the upper airway collapses throughout sleep, affecting a complete or partial interruption of airflow even with sustained respiratory struggle. The sympathetic tone is stimulated, and respiratory work increases as opposed to the closed upper airway, increasing negative intrathoracic pressure. Stimulation of the sympathetic tone across the parasympathetic system affects heart rate and blood pressure.10 Awakening from sleep terminates the asphyxia event, with re-establishing airflow and re-oxygenation but further increased sympathetic tone. Obstructive sleep apnea seems to be correlated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, metabolic dysregulation is observed in obstructive sleep apnea patients (with abnormalities in both fat and glucose metabolism. This contributes to atherosclerosis and endothelial damage with enhanced arterial stiffness. However, it remains unclear whether metabolic abnormalities and inflammation are exacerbated by obstructive sleep apnea, whether these are epiphenomena are due to obesity.10

Hypertension

Obstructive sleep apnea is common in middle-aged and older people, although hypertension is also prevalent among middle-aged and older people. This increases the chance of significant complications between hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. The level of the complications of hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea is significantly greater than expected. Hypertension is prevalent in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and contributes to vascular injury and cardiovascular events. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms contribute to the increased risk of hypertension in individuals with obstructive sleep apnea, including upregulation of neurohormonal pathways, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation.6 Although patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher incidence of hypertension,11 the inverse is also true because patients with hypertension are more likely to experience sleep-disordered breathing, especially those who have failed to respond to traditional treatment. Up to 84% of this subset of patients may have undetected obstructive sleep apnea.12 Animal experiments have provided direct proof that obstructive sleep apnea causes hypertension. When obstructive sleep apnea is induced, it results in acute transient rises in nighttime blood pressure and ultimately culminates in persistent daytime hypertension.11 When blood pressure is strictly regulated in rats, it also decreases sleep apneas.13 In humans, a causal link between obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension has not been established because variables such as age and obesity confound the association. However, epidemiological data suggest that hypertension was found in approximately 50% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea.7

Dyslipidemia

Obstructive sleep apnea is commonly associated with elevated plasma triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), and total cholesterol. Moreover, the reduction in highdensity lipoprotein (HDL) may, in part, be due to deleterious oxidative processes commonly found in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.14,15,16 The effect of treating obstructive sleep apnea in children with adenotonsillectomy is variable as regards the impact on lipid profiles17 because chronic intermittent hypoxia may affect both lipid biosynthesis and lipid peroxidation.18

Type 2 Diabetes

Inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes is characterized by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines or a rising number of white blood cells in the blood or tissue. Stimulation of the inflammatory process often indicates abnormalities such as tissue injury and organ dysfunction. Obesity might cause chronic low-grade inflammation and hat is involved in type 2 diabetes. In addition, adiposespecific cytokines (leptin adiponectin, leptin, and interleukin 6 (IL-6)) are secreted by visceral adipocytes and inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)). An elevated amount of fatty tissue draining into the chemokines, portal vein, and IL-6 production can induce liver and systemic insulin resistance.19,20 Although obesity is a serious risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus, coexistent severe obstructive sleep apnea may independently add to the risk. The relationship between intermittent hypoxia and insulin resistance21 has been assessed by evaluating the effect of hypoxia–reoxygenation cycles

on insulin target tissues. Rodent models suggest that chronic exposure to intermittent hypoxia induces insulin resistance.22

Atrial Fibrillation

Obstructive sleep apnea is a common risk factor for atrial fibrillation.23 Recurrent episodes of obstructive sleep apnea may lead to cardiac structural and electric remodeling. Repetitive episodes of obstructive sleep apnea in an animal model can cause atrial fibrosis and important changes in connexin-43 distribution and expression, thus leading to slow atrial conduction. This increases the vulnerability to arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation.24 Furthermore, untreated obstructive sleep apnea doubles the risk of recurrence of atrial fibrillation in patients after electrical cardioversion. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP attenuates the risk of atrial fibrillation.25 Obstructive sleep apnea shares many common risk factors with atrial fibrillation. The prevalence of both atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea is rising due to increases in obesity and cardiovascular disease. The close association between obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease, and atrial fibrillation and cardiovascular disease may obscure a directly causal relationship between atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. The interplay of the pathophysiology of these chronic diseases is complex and likely bidirectional. Obstructive sleep apnea may contribute to atrial fibrillation, and, in turn, atrial fibrillation promotes the development of obstructive sleep apnea. Nonetheless, these entities are associated with one another, independently of other cardiovascular diseases.26

Heart Failure

Sleep apnea is predictable in patients with heart failure, with a prevalence of between 50% and 70%.27 Mainly, central sleep apnea accounts for two-thirds of the sleep apnea cases in this population, while obstructive sleep apnea is less frequent. Central sleep apnea is a frequent concomitant finding in patients with severely impaired cardiac function.27 Another study aimed to assess the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing and its associated risk factors in French patients with heart failure showed that 30% of syndromes were classified as central and 70% as obstructive.28 Coexisting sleep apnea in patients with heart failure has been associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes, including mortality.29 Several pathophysiological processes resulting from apneic events may explain this association. These involve stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system30 and increased preload and afterload resulting from perturbation of intrathoracic pressure while struggling to inspire against blocked airways.31 Worsening hypertension, increased risk of arrhythmias including sudden cardiac death,32 and myocardial infarctions33 are other mechanisms by which sleep apnea may worsen outcomes in patients with heart failure.34

The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular events remains unclear. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Loke, Yoon K., et al. suggested that obstructive sleep apnea may be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular, stroke, and overall mortality. Due to imprecision and inconsistencies in the data, the strength of potential association between obstructive sleep apnea and ischemic heart disease remains unclear.35 A cohort study evaluating the relationship between obstructive sleep apnea-related variables and the risk of CV events revealed that several obstructive sleep apnea-related factors other than the apnea–hypopnea index were important predictors of a composite CV outcome.36 Hence, the need for a randomized controlled trial is crucial.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Reduces Risk Factors for Myocardial Infarction, Atrial Fibrillation, and Heart Failure

Randomized controlled trials demonstrated that CPAP lowers blood pressure by 2–3 mm Hg.37 Among patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension, CPAP treatment for 12 weeks decreased the 24 h mean and diastolic blood pressure and increased the nocturnal blood pressure.38 CPAP also improved dyslipidemia (decrease in total cholesterol and LDL and increase in HDL). This may contribute to a potential reduction in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.39 In patients with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea, compliant CPAP usage may improve insulin secretion and insulin resistance. The latter was associated with an improvement in leptin even after short-term CPAP therapy.40,41 Both epidemiological studies and cohort studies suggest that CPAP reduces atrial fibrillation recurrence risk after cardioversion and ablation.42,43 In 426 individuals undergoing pulmonary vein isolation, 62 patients with verified obstructive sleep apnea who used CPAP had a higher rate of atrial fibrillation-free survival than those who did not use CPAP (72% vs. 37%). The atrial fibrillationfree survival rate among CPAP users was comparable to that of individuals without obstructive sleep apnea. However, randomized controlled trials are still awaited.44 Not surprisingly, given the association between obstructive sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation, there is also an association between obstructive sleep apnea and stroke.45,46 CPAP may attenuate this risk,46 but this has not been studied prospectively.

CPAP Does Not Reduce Myocardial Infarction

The potential associations of CPAP to reduce composite cardiovascular events, all-cause, and cardiovascular death in patients with concomitant cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnea rely on data from observational studies.47 There is currently no level 1 evidence to suggest that CPAP can prevent future cardiovascular events in patients, including obstructive sleep apnea and coronary artery disease.48 A randomized controlled trial that studied the impact of CPAP on cardiovascular outcomes showed no reduction in long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the intention-to-treat population.49 A clinical trial comparing usual care with usual care plus CPAP therapy

found that the addition of CPAP did not prevent cardiovascular events in patients with moderateto-severe obstructive sleep apnea and preexisting cardiovascular disease.50 However, no significant beneficial effects of CPAP were shown in patients with obstructive sleep apnea in the trials evaluating CPAP therapy on major adverse cardiovascular events.49,50,51 CPAP did not reduce the rate of complex cardiovascular events at a median follow-up of 3.7 years in the SAVE (Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints) trial that randomized 2717 participants with cerebrovascular disease with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea or.50 Furthermore, no effect of CPAP therapy on major adverse cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea with or without cardiovascular morbidities was shown in several metaanalyses of randomized trials.52,53,54 However, the study populations of the included studies are diverse, from the general population to patients with severe coronary artery disease (such as myocardial infarction), thus precluding definitive conclusions.

Obesity

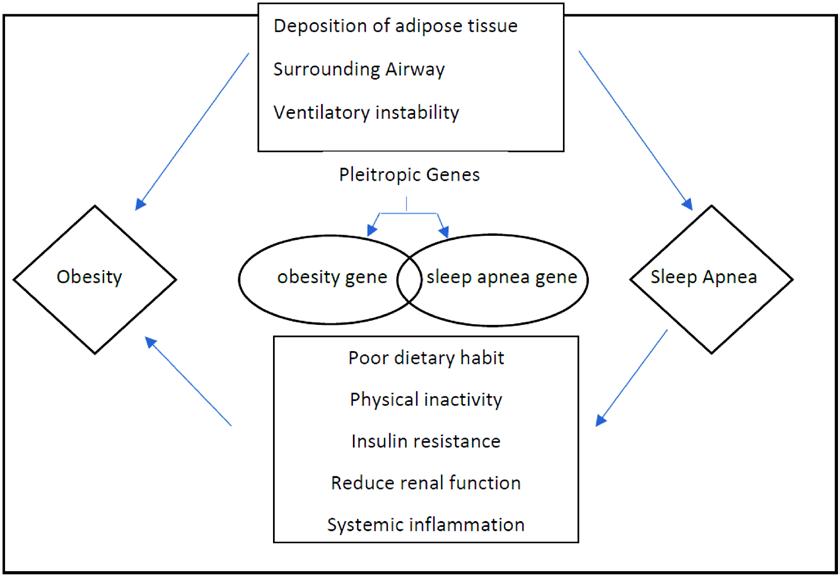

Obesity is a chronic multifactorial disease. Obesity is caused by inherited biological and ecological factors, diet, physical activity, and exercise choices. It is a medical problem that raises the threat of other diseases and health problems, such as high blood pressure, certain cancers, diabetes, and heart disease.55 Various risk factors, involving obesity, age, sex, heritable and race/ethnicity factors, are wellknown in the pathogenesis of sleep apnea. However, obesity has usually been known to be one of the most significant sleep apnea risk factors.56 Some crosssectional experiments have always found a connection between the obstructed sleep apnea risk and body mass index. The registered prevalence of sleep apnea ranges from 40% to 90% in individuals with a body mass index > 40 kg/ m2 (severe obesity).57,58 Significant sleep apnea appears in over 70% of sleep apnea patients with obesity and 40% of people with obesity.59 Obesity is the only major obstructive sleep apnea risk factor that is variable. Weight decrease in the short term of one to two years steer to better metabolic control in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.60 A prospective study of Wisconsin citizens indicated that a 10% weight loss anticipated a 26% reduction in the sleep apnea severity apnea–hypopnea index [58]. Moreover, another cohort research observed decreased apnea occurrence after weight loss.61 Even though the mechanisms by which weight loss decrease obstructive sleep apnea symptoms are not entirely understood, factors such as decreased visceral fat deposition play an important role.62 Airway structures and altered neurophysiologic control of respiration during weight loss are likely also important.63 Moreover, obesity may control the chemoreflex function through neurohormonal mediators such as leptin, which reduces when sleep apnea patients lose weight.60 Therefore, these potential methods likely work in concert to act as a vicious cycle in the body weight gain pathogenesis and obstructive sleep apnea (Figure 1 on page 63). Obesity complications such as hypertension, diabetes, insulin resistance, and obstructive sleep apnea increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases.64 Obesity may also independently contribute to atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.47,65,66,67 To prevent or reverse obesity complications, more than 10% weight loss may be required,68 and the previously suggested 5% to 10% weight loss may not be sufficient.69,70 In the case of obesity, evaluation before the intervention should include a comprehensive weight history, a complete individual and family medical history, blood studies, a physical examination looking for signs of the complications of obesity, and a behavioral history.71 This approach may identify primary causes for weight gain, such as an endocrine disorder, medications linked with weight gain, an underlying eating disorder, or differences in the condition that have led to decreased activity and an energy imbalance. Body mass index and waist circumference should also be included in this initial evaluation. Blood tests should consist of a measurement of thyroid function, insulin sensitivity, liver function, and lipid profile.71 Once a diagnosis of obesity has been made, the management of obesity should be stratified.

Weight Loss as a Treatment to Reduce Cardiovascular Events

Currently, no randomized control trials have shown that intentional weight loss reduces the cardiovascular death risk.73,74,75 Non-randomized long-term follow-up data from a prospective cohort Swedish Obese Subjects study showed that bariatric surgery resulted in reduced cardiovascular mortality and occurrence of first-time (fatal and nonfatal) cardiovascular events.76 The Look AHEAD clinical trial was designed to assess the long-term effects of nutritional therapy and exercise therapy delivered over ten years in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes. The primary outcome was time to the incidence of a major cardiovascular disease event. The study revealed that weight loss produced improvements in HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, HDL triglycerides, and cholesterol at years 1 and 4 (all p ≤ 0.02),77 but no changes in cardiovascular events over ten years.77 However, the subgroup of patients who lost more than 10% of their weight did have a reduction in mortality.78 Another two-year follow-up cohort study also demonstrated that 5–10% weight loss improves risk factors but not cardiovascular events.79

Weight Loss as a Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Although weight loss can facilitate obstructive sleep apnea treatment, it can rarely cure it and still requires a combination with continuous positive airway pressure.80 A systematic review and metaanalysis conducted to assess the effect of lifestyle therapy on the oxygen desaturation index, apnea–hypopnea index, and excessive daytime sleepiness among adults revealed significant reductions in all these components after weight loss. However, most patients still had diagnosable obstructive sleep apnea.81 The SCALE sleep apnea study compared the effects of 3.0 mg liraglutide to placebo on obstructive sleep apnea severity and body weight loss in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. This study showed that 3.0 mg liraglutide produced greater reductions in ischemic heart disease, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and HbA1c in patients with obesity with moderate/severe obstructive sleep apnea, but most patients still had diagnosable obstructive sleep apnea at the end of the study.82 A prospective multicenter study investigated the effects of a laparoscopic Roux–en–Y gastric bypass. One year after surgery, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea decreased, but more than half of those with obstructive sleep apnea at baseline still had it after surgery. Obstructive sleep apnea was cured in 45% and improved in another 33% of the patients, but moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea persisted in 20% of

Table 1. Summary of weight loss as a treatment for cardiovascular events risk reduction, obstructive sleep apnea and to reduce cardiovascular events in patients Table 1. Summary of weight loss as a treatment for cardiovascular events risk reduction, obstructive sleep apneawith obstructive sleep apnea. and to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Weight loss as a treatment to reduce cardiovascular events

Nonrandomized long-term follow-up data from the prospective cohort Swedish Obese Subjects study showed that bariatric surgery resulted in reduced cardiovascular mortality and occurrence of first-time (fatal and nonfatal) cardiovascular events. The Look AHEAD clinical trial showed no changes in cardiovascular events over ten years.

Weight loss as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea

Systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that lifestyle interventions cause significant reductions in the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI), oxygen desaturation index (ODI), and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) among adults, but all patients still had diagnosable obstructive sleep apnea. The SCALE sleep apnea study showed that 3.0 mg liraglutide produced greater reductions in the apnea–hypopnea index.

Weight loss as a treatment to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea

Weight loss intervention is an effective strategy to improve cardiovascular risk in patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea [66], but whether this will reduce cardiovascular events remains to be determined.

the patients after the operation.83 A recent prospective cohort study showed that patients with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea may lose less weight with bariatric surgery than those with milder disease.84 A systematic review included 19 surgical (n = 525), and 20 nonsurgical (n = 825) studies assessing the body mass index and the apnea–hypopnea index before and after intervention.85 The results showed that bariatric surgery and nonsurgical weight loss both had beneficial effects on obstructive sleep apnea through body mass index and apnea–hypopnea index reduction. However, bariatric surgery may result in a significantly greater improvement in the body mass index and the apnea–hypopnea index than nonsurgical alternatives.85 The exact relationship between bariatric surgery and nonsurgical weight loss interventions in OSA resolution remains a challenge due to the need in randomized controlled trials.85

Weight Loss as a Treatment to Reduce Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Cardiovascular events are the primary cause of mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity [86]. CPAP combined with weight loss may improve obstructive sleep apnea pathophysiology and the apnea–hypopnea index and reduce cardiovascular risk.87,88 A randomized 24-week trial on 181 patients with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and obesity comparing the effects of CPAP, weight loss, or combined CPAP and weight loss was conducted. Combining CPAP and weight loss did not reduce CRP levels more than either intervention alone. Weight loss provided an incremental reduction in serum triglycerides and the insulin resistance level when combined with CPAP. Weight loss and CPAP did incrementally reduce blood pressure compared with either intervention alone [89]. Another randomized control trial of 42 patients with obesity, severe obstructive sleep apnea (apnea–hypopnea index > 30 events/h) and treated with CPAP for a minimum of 6 months before the study allocated patients to an intensive weight loss program or standard lifestyle recommendations over 12 months. The effect of weight loss was assessed on obstructive sleep apnea severity and metabolic variables. The intensive weight loss program effectively reduces weight and obstructive sleep apnea severity while also improving lipid profiles, glycemic control, and inflammatory markers [90]. The authors concluded that weight loss intervention is an effective strategy to improve cardiovascular risk in patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea,66 but whether this will reduce cardiovascular events remains determined.

Table 1 (bottom of page 64) summarizes the available data assessing the effect of weight loss as a treatment for cardiovascular events risk reduction, obstructive sleep apnea, and to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. This potential relationship is plausible because of prevailing pathophysiological mechanisms, but definitive evidence is still lacking. There is evidence that treatment with CPAP decreases blood pressure, but the impact of weight loss in patients with resistant hypertension is more profound than in those with acute obstructive sleep apnea. Current data supporting the impact of CPAP on cardiovascular events come from nonrandomized studies, and higher-quality evidence is needed to change clinical practice. We also require using the concept of individualized medicine for this matter and focusing on genetic variations and why a few patients with OSA develop cardiovascular effects while others do not. Such research will assist in reporting on the clinical trials that are required to be performed. Weight loss in patients with obstructive sleep apnea produced improvements in HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides, but thus far, no changes in cardiovascular events have been shown. This will require cooperation among specialists in cardiology and sleep apnea.

Conclusions

Despite the association between cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnea, randomized trials have failed to demonstrate that obstructive sleep apnea treatment improves the outcomes of cardiovascular events, even in patients with established cardiovascular disease.50 The combination of weight loss with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) appears to be more helpful than either treatment in isolation. Large well-controlled trials in patients with obstructive sleep apnea to evaluate the impact of different weight reduction programs on cardiovascular disease are still required.

References available on request

News

Improving Outcomes in Childhood Obesity

New research from RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences has analysed the impact of Ireland’s only obesity service for children and adolescents. Care Group and published in Frontiers in Nutrition, found that the W82GO Child and Adolescent Obesity Service at CHI Temple Street improves obesity-related outcomes for children and adolescents.

The W82GO Service is the only dedicated centre for paediatric and adolescent obesity management in the Republic of Ireland. It delivers tailored obesity interventions, including dietetic, psychological, medical, physiotherapy and medical social work support, as recommended by scientific guidelines. As part of the W82GO Service, patients are referred by a paediatrician and then assessed by a physiotherapist, dietician and psychologist to develop personalised obesity treatment plans with the family, based on the child’s age and clinical need. In this study, the researchers looked at outcomes for almost 700 children and adolescents from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds who had engaged with the service over 12 years. By comparing growth chart data from the baseline and final visit, they demonstrated an overall reduction in sex- and age-adjusted BMI across the cohort, indicating that engagement with the W82GO Service is linked to improvements in health. The findings showed that younger children especially benefited from the treatment. RCSI School of Physiotherapy and senior author on the paper, commented on the findings, “Childhood obesity is a chronic disease that requires multidisciplinary and specialist intervention, however, access to treatment is limited globally. We must evaluate the impact of evidence-based interventions in real-world settings in order to increase the translation of research into practice and enhance child health outcomes.

“Our research shows that the W82GO Service is an important intervention for managing severe obesity in children and young people. In particular, we found that the intervention was especially impactful for younger service users, and those who engaged in the service for more than 12 months.”

Dr Grace O’Malley, Lecturer in the RCSI School of Physiotherapy

First National Survey on HIV-Related Stigma

Researchers at NUI Galway are aiming to use a national survey into HIV-related stigma in healthcare settings to tackle the issue and improve health outcomes for people with the disease.

The first Joint National Survey on HIV-related stigma in healthcare settings will mean Ireland will be the first country in Europe that will have this kind of national-level data.

The study was launched by researchers at the Health Promotion Research Centre in NUI Galway. It can be accessed at www.nuigalway.ie/ hiv-stigma-survey.

It is the first of its kind in Europe as the researchers aim to learn both from people living with HIV and also those who provide healthcare for them.

The survey aims to measure stigma in healthcare settings, and is part of a wider study to develop guidelines to reduce HIV-related stigma and improve healthcare outcomes for people living with HIV.

Dr Elena Vaughan, NUI Galway researcher and principal investigator on the Addressing HIV-stigma in Healthcare settings study, said, “This research will help us to get a sense of what the needs and priorities are - both of people working in healthcare and people living with HIV - so that a collaborative approach may be taken to address stigma in healthcare settings.

“Experiences of stigma in healthcare settings can put people off engaging with healthcare services. This can have negative impacts on a person’s health. There is also evidence to suggest that stigma inhibits people from accessing testing and treatment, and so is a driver of the epidemic more broadly.”

Approximately 7,000 people are living with HIV in Ireland. Massive strides in the treatment of HIV mean that it is now easily managed with medication. People living with HIV are living long healthy lives and cannot pass on the virus when they are on effective treatment. However, stigma remains a serious problem for many people living with HIV, and this can affect their health and well-being

Reducing HIV-related stigma is widely acknowledged as a key part of addressing the HIV epidemic.

In 2019, Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Galway were signed up to the Fast Track Cities Initiative – a global collaboration between UNAIDS, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC), and 300 cities and municipalities worldwide. The objective is to work towards reaching zero new HIV infections, zero AIDS-related deaths, and zero HIV-related stigma and discrimination by 2030. Stigma reduction is also a stated aim of the Sustainable Development Goals, to which Ireland has also committed.

Dr Vaughan added, “Stigma in healthcare settings is among the key indicators recommended by UNAIDS to measure and evaluate the HIV response in individual countries. In addition to providing important information to help us reduce stigma in healthcare settings, the data generated from this project will be useful to programme and policy-makers in tracking progress in meeting commitments both to the SDGs and the Fast Track Cities Initiative. Ireland will be the first country in Europe that will have this kind of national-level data.”

The survey is being launched just ahead of Irish AIDS Day on June 15, 2022 and will be live for the month of June.

The project is supported by HIV Ireland and funded by the Irish Research Council.

Dr Elena Vaughan, Health Promotion Research Centre, NUI Galway, Credit - Aengus McMahon

The European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) has established a Special Interest Group (SIG) to gain more knowledge about the current and future use of prefilled medicines syringes (PFS) in hospitals. EAHP’s SIG focused on the Use of Prefilled Syringes in Intensive Care Units and Operating Theatres (financially supported by BD) has prepared two surveys targeting on the one hand professional associations and on the other hand health professionals and managers. A PFS is a presentation of one or more active medicines, at the required concentration and volume, in the final syringe and ready for parenteral administration to the patient. PFS are intended to reduce error and minimise the time taken to prepare parenteral medicine by staff in clinical areas. PFS are manufactured/prepared by the pharmaceutical industry or hospital pharmacies. Several additional benefits and some disadvantages have been reported for PFS. The SIG is preparing a comprehensive literature review on PFS.

Usage of PFS in hospitals in North America has been considerably larger than in Europe for many years. Recently the use of PFS in some European countries has increased.

The surveys have been designed to collect the views and opinions of a range of health professionals, managers, and professional associations on the current and future use of PFS. Participation is completely voluntary. It should take approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete the survey. Feedback can be shared until the 31st of August 2022. The survey for professional associations is available in English. The survey for individual health professionals and managers can be completed in eight different languages (English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Serbian, Spanish and Turkish). EAHP’s SIG thanks the survey participants in advance for their participation.

64

Cystic Fibrosis Current Trends in Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an inherited chronic disease, primarily affecting the lungs and digestive system of over 1,300 children and adults in Ireland and 70,000 people worldwide.1 Between 2008 and 2016, an average of 38 individuals in Ireland were diagnosed with CF each year, with 22 diagnosed in 2016.5 Ireland has the highest incidence per head of population of CF in the world, with three times the rate of the United States and the rest of the European Union.1 We spoke with Theresa Lowry Lehnen, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Associate Lecturer Institute of Technology Carlow to learn more about this lifelong condition. The symptoms and severity of cystic fibrosis vary from person to person. The majority of people have both respiratory and digestive problems. There is no cure for cystic fibrosis, however, life expectancy has increased steadily over the past 20 years, and today cystic fibrosis is no longer exclusive to childhood. At the beginning of each year, the CF Registry of Ireland (the ‘registry’) conducts a survey of hospitals known to provide care to people with CF in the Republic of Ireland. The registry has gathered information on people with CF since 2002. The annual hospital census carried out by the registry in 2016 showed that 1,339 people were living with cystic fibrosis (PWCF) in Ireland. Most patients attended one hospital for CF care (n=1,107, 82.7%), whereas 17.3% (232) shared care at two or more hospitals. 2016 was also Interview with Theresa LowryLehnen (PhD), CNS, GPN, RNP and National PRO Irish General Practice Nurses Educational Association

the first time that the median age for PWCF reached 20 years (half of the population over 20 years and half under) while 8.9% of the PWCF population in Ireland was recorded as over 40 year’s old. There were 1,266 individuals (565 children and 701 adults) with CF on the registry on the last day of 2016, representing 94.5% of people living with CF in Ireland in that year. Theresa told us, “About 2,000 CFTR gene mutations have been identified to date. Genetic testing provides important information to assist the diagnosis and treatment of cystic fibrosis. F508del is the most commonly detected CFTR mutation in Irish people living with CF.

“In 2016, 91.6% of the CF population had at least one copy, 15.2% at least one copy of G551D, and 5.8% at least one copy of R117H. All other CFTR mutations affect less than 5% of the CF population. Fifty-five percent of patients (55.6%) living with CF in Ireland in 2016 had two copies of the F508del mutation (F508del homozygous). This compares with 46.1% in the United States and 50.3% in the United Kingdom in 2015. Thirtysix percent (36.0%) of people had just one copy of the F508del mutation (F508del heterozygous). The F508del homozygous mutation is the most common CFTR gene mutation in people under 40 years. In those over 40, F508del heterozygous mutations are most common.”5

Cystic fibrosis affects multiple organ systems including the lungs, pancreas, upper airways, liver, intestine, and reproductive organs to varying degrees. Early diagnosis provides opportunities for earlier medical intervention.

Providing infants with the best possible care results in better nutritional and lung function outcomes later in life, says Theresa. “Optimised treatment prolongs the lives of people with cystic fibrosis, improving their quality of life,” she says. “Improved diagnosis and symptomatic treatments have increased the survival rates of people with the condition, from a life span of only a few months in the 1950s to a global median age of 40 years today. The predicted median age of survival for a person in Ireland with CF is early to mid-30’s.”

Cystic fibrosis is caused by a gene mutation leading to dysfunction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, a chloride channel of exocrine glands. The defect leads to diminished chloride secretion which, in turn, leads to increased sodium absorption through epithelial sodium channels and removal of water from secretions, which become abnormally viscous. “The effects cause obstruction, inflammation, infection in the lungs and upper airways, tissue reorganisation and loss of function. The severity of the disease in the individual depends on variable organ sensitivity and on the genetically determined residual function of the CFTR protein. 99% of affected male patients are infertile because of obstructive azoospermia, and 87% of patients have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Disease severity particularly the degree of pulmonary involvement, also depends on other diseasemodifying genes and a number of factors including socioeconomic background,” says Theresa.2, 3

Diagnosis

Most cases of cystic fibrosis are diagnosed through screening tests, which are carried out early in life. However, some babies, children and even young adults are diagnosed later following unexplained illness.

Symptoms

Theresa explains, “People with cystic fibrosis present with a variety of symptoms, including, very salty-tasting skin, persistent coughing with phlegm, frequent lung infections, wheezing or shortness of breath, poor growth/ weight gain despite a good appetite and frequent greasy, bulky stools or difficulty in bowel movements.1

“Symptoms usually appear in the first year of life, although occasionally they can develop later. The thick, viscous mucus in the body affects a number of organs, particularly the lungs and digestive system. Typical respiratory symptoms include cough and wheeze. Recurring chest and lung infections are caused by the continual buildup of mucus in the lungs, which provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria.7 Organisms detected in the airways of individuals with CF in Ireland in 2016 included Staphylococcus aureus (54.7%) and Haemophilus influenza (29.0%) found most frequently in children. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was detected in at least one respiratory sample of 60.3% of adults.5 Two strains of bacteria that commonly infect people with cystic fibrosis are Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia complex. They multiply in the thick mucus inside the lungs and may cause serious health problems and repeated chest infections. As more and more people with cystic fibrosis become infected with these bacteria, the bacteria become resistant to antibiotic treatment, which is why crossinfection is such a problem. Lung infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus can become chronic, and cause an irreversible reduction in lung function.5, 7

“Chronic disease of the lungs and paranasal sinuses varies among patients with cystic fibrosis and can be difficult to distinguish from frequent recurrent bouts of bronchitis and/or pneumonia, especially in young children. Children with cough, sputum production, or wheezing of more than three months’ duration, persistently abnormal radiological findings, persistently positive bacterial cultures of respiratory secretions, or clubbing of the fingers should undergo diagnostic testing for cystic fibrosis even if their neonatal screening test was negative. The same applies for children with bilateral chronic rhinosinusitis with frequent exacerbations, with or without nasal polyps.2

“Cystic fibrosis causes mucus to block the ducts in the pancreas leading to malnutrition, steatorrhoea and diabetes. People with cystic fibrosis who develop diabetes may find it difficult to gain weight or may lose weight and see a decline in their lung function. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes is usually controlled by regular injections of insulin. Diabetes rarely occurs in children with cystic fibrosis.6

“Pancreatic insufficiency (PI) is manifested by voluminous, fatty, shiny, malodorous, pulp like stools, abdominal symptoms, dystrophy, and deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins (e.g., hemolytic anemia due to vitamin E deficiency) and trace elements (e.g., zinc dermatosis). The diagnosis can be established by a low fecal elastase measurement. Patients with primary pancreatic insufficiency are at increased risk of chronic and/or recurrent pancreatitis.”4

In addition, Theresa reveals that people with cystic fibrosis are also prone to sinusitis and hay fever. She continues, “Older children with cystic fibrosis can develop a form of arthritis in joints such as the knee which improve with time and treatment. Older children and adults are prone to osteoporosis due to, repeated infection, poor growth or weight, lack of physical activity and lack of vitamins and minerals due to digestive problems. People with cystic fibrosis are more at risk of developing osteoporosis if they are taking steroids to help with lung infections. Osteoporosis as a result of cystic fibrosis may cause joint pain and cause bones to fracture more easily. Bisphosphonates are taken to help maintain bone density.6

“One in ten babies with cystic fibrosis is born with meconium ileus and an operation to remove the blockage will probably be required.6 In nearly all men with cystic fibrosis, the spermatic tubes do not develop correctly, making them infertile. Women with cystic fibrosis may find their menstrual cycle becomes absent or irregular if they are underweight. There is also an increased thickness of cervical mucus, which may reduce fertility. However, most women with cystic fibrosis can conceive without any difficulty.6 If the bile ducts in the liver become blocked by mucus as the disease progresses, this can be serious and in some cases a liver transplant may be necessary.”6

Treatment

There is no cure for cystic fibrosis. The aim of treatment is to clear and control infections in the lungs and digestive system, and reduce long-term damage caused by infection and organ complications.

Talking about current treatments, Theresa says, “Inhaled bronchodilator drugs are treatments used to relax the muscles surrounding the airways and help the person breathe more easily. Antibiotics are prescribed to treat infections in the lungs. All young children diagnosed with cystic fibrosis are started on a course of oral antibiotics to protect them from certain bacteria, which will be continued until they are three years of age. The number of days spent on IV antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbation for all people with CF in Ireland in 2016 came to a total of 14,084. The mean duration of pulmonary exacerbation treatment was 16.4 days and median duration was 14 days.5 Steroids are used to help reduce the swelling of the airways, which can help with breathing and DNase an enzyme, which is usually inhaled, is used to help thin and break down the viscous mucus in the lungs, so it is easier to expectorate.6

“Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) is required by almost all individuals with CF, due to pancreatic insufficiency. When the exocrine pancreas no longer functions adequately, the production of pancreatic enzymes is reduced, leading to fat malabsorption. The consequences of this include steatorrhoea, malnutrition, and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies. Ninety-one percent of patients with CF in Ireland received PERT in 2016. Supplementary feeding can be required due to continued weight loss. Nearly 38% of individuals with CF required supplemental feeding in 2016. Approaches to supplemental feedings included oral supplementation, gastrostomy tube/button feeding, nasogastric tube feeding and total parenteral nutrition.5

“Pancreatic enzymes are taken before and during every meal and fat-containing snack or drink helping the digestive system break down food so that it can be digested and absorbed. The number of enzyme capsules taken needs to be adjusted depending on the amount of fat in the meal, snack or drink. The enzymes should be taken with the meal and the timing may vary depending on the age of the person with cystic fibrosis. It is essential that people with cystic fibrosis receive advice about enzymes from a specialist cystic fibrosis dietitian. Fat-soluble vitamin supplements (A, D, E and K) are taken to help replace lost vitamins and to prevent deficiencies. Because people with cystic fibrosis lose fat in their stools, they also lose the fat-soluble vitamins. Nutritional supplements can help compensate for poor digestion and provide additional energy and nutrients.”5, 6

People who have diabetes as a result of their cystic fibrosis, need to take insulin and manage their diet to control blood glucose levels.

Bisphosphonates are taken to treat osteoporosis, which can occur as a result of cystic fibrosis to help maintain bone density and reduce the risk of fractures. “It is important that people with cystic fibrosis are up to date with all the required vaccinations and should have the flu vaccine annually, as they are more susceptible to complications as a result of infection,” she adds.6

Daily physiotherapy is usually required and, if the person with cystic fibrosis has a chest infection the amount of airway clearance will need to be increased. Physiotherapy is tailored to the individual’s needs. While physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis mainly focuses on airway clearance, the role of physiotherapy in cystic fibrosis has expanded to include daily exercise, inhalation therapy, posture awareness and in some cases for the management of incontinence.6

“A specialist CF physiotherapist will assess a person with cystic fibrosis and recommend the most appropriate techniques to use. Techniques may change as the person gets older or as their disease progresses. Some airway clearance techniques are done without the need for equipment and focus on specific breathing exercises, such as the active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) and autogenic drainage. Other techniques use devices to help with the clearance of mucus. These devices use positive pressure to hold open the airways while some create vibrations. Techniques include positive expiratory pressure (PEP), oscillating positive expiratory pressure and high frequency chest wall oscillation (HFCWO).6

“In severe cases of cystic fibrosis, when the lungs stop working properly and all medical