24 minute read

An overview of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

An overview on BPH (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia)

Definition:

BPH (benign prostatic hyperplasia) refers to the non-malignant growth or hyperplasia of prostate tissue. A benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) can cause bladder Outflow Obstruction (BOO) and is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)in men.

Epidemiology:

The prevalence of histological BPH increases with age, affecting approximately 42% of men between the ages of 51 and 60 years and 82% of men between the ages of 71 and 80 years.1 The global lifetime prevalence of BPH is around 25%.2

Aetiology & Pathophysiology:

Hyperplasia in the prostate is stimulated by androgens. The main androgen is dihydrotestosterone, which is converted from testosterone by the enzyme 5-alpha reductase. Lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from hyperplasia are mainly due to 2 components: a static component related to an increase in benign prostatic tissue mainly at the transitional zone, narrowing the urethral lumen and a dynamic component related to an increase in prostatic smooth muscle tone mediated by alpha-adrenergic receptors.3 The aetiology is multifactorial with advancing age, endogenous androgens and prostate volume increasing the risk of developing symptoms. Black men appear to have a higher risk and Asian men have a lower risk.4 Potential causal risk factors include Obesity, smoking, male pattern baldness, family history of BPH & metabolic syndrome. Progression from pathologic BPH to clinical BPH (i.e., the presence of symptoms) may require additional factors such as prostatitis, vascular effects, and changes in the glandular capsule.5

Making the Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) can often be suggested based on the history alone. In men above the age of 50, history and symptoms suggestive of BPH include possible voiding and storage symptoms. Voiding symptoms include hesitancy, intermittency, weak stream, straining, incomplete emptying & post void dribbling. Storage symptoms include urinary frequency, nocturia, and urgency. A small proportion of men present with the inability to pass urine and is associated with suprapubic pain and a palpable bladder, which is a complication of untreated BPH. This is a urological emergency and the bladder requires immediate drainage. Men presenting under the age of 50 with voiding LUTS are unlikely to have BPH.

Examination:

Examination for BPH begins with abdominal, digital rectal examination(DRE) and a focused neurological examination. The DRE should assess perianal sensation, anal tone, prostate size and for any prostatic irregularity. A prostate nodule on DRE should prompt PSA levels. Decreased anal sphincter tone or the lack of a bulbocavernosus muscle reflex may indicate an underlying neurological disorder.

Investigations:

All patients should have a urine dipstick and/or culture and sensitivity to rule out a UTI or haematuria. NICE guidelines recommend that all patients with LUTS suggestive of renal impairment should have a serum creatinine and eGFR. If renal impairment is present, an ultrasound scan should be requested to assess for hydronephrosis and post-void residual. Patients should be advised to record a frequency/volume chart voiding diary for a few days, which is a useful tool to objectify symptoms and detect polyuria.6 Assessment of the severity of the patient’s symptoms and the impact on their quality of life is done using the IPSS (International Prostate Symptom Score), a selfadministered questionnaire with 8 questions.7 (Image 1 on page 17) Investigations may include a urinary flow rate and post-void residual estimation. Post-void residuals greater than 200ml may indicate a less favourable response to treatment.

Urodynamic or Pressure flow studies provide the most complete means of determining the presence of outlet obstruction, but its use is optional.7 Written by Jasim Siddiqui, MBBS, Urology Registrar at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital & Mr Ronan Long, MB, BCh, BAO, MCh, MMed SCI, FRCS(Urol), Consultant Urologist at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Louth County Hospital and Mater Private Outreach Clinic Drogheda.

A transrectal or abdominal ultrasound & cystoscopy is considered in assessing Prostate size, shape & morphology, which play an important role in decision-making for the treatment and differential diagnosis of male LUTS/BPH.

Role of PSA in BPH

PSA has a useful role in the assessment of LUTS by acting as a surrogate marker in benign disease for an enlarged prostate. The weight of evidence suggests that men with a PSA >1.4ng/ml should be considered at increased risk of disease progression of BPH.8,9 A note of caution should remain that a PSA test cannot replace a DRE and should not be done in its absence.

The presence of BPH symptoms does not predispose to prostate carcinoma and therefore it is not essential in men with BPH unless an abnormal prostate is felt on DRE or the patient is specifically concerned about or has a family history of prostate carcinoma [10]. The NICE guidelines also recommend that a PSA test is offered only after full counselling. One must also exclude a UTI prior to a PSA test and not perform the test within a month of a proven UTI.

Approach To Treatment:

The aim of treating BPH with LUTS is to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life, as well as to attempt to prevent progression of disease and the development of complications. These aims need to be balanced against the potential side-effects of treatment. Therefore, watchful waiting is an option recommended for many men. Watchful waiting is the recommended strategy for patients with BPH who have mild symptoms (International Prostate Symptom Score ≤7) and for those with moderate-to-severe symptoms (IPSS score ≥8) who are not bothered by their symptoms and are not experiencing complications of BPH. In patients

with mild symtoms, medical therapy is not likely to improve their quality of life.11 These Patients may also benefit from behavioural and lifestyle modifications including reducing fluids at night, limiting caffeinated and alcoholic beverages, avoiding, or modifying the timing of diuretics or medications that increase urinary retention, and use of techniques to help control bladder symptoms. Patients managed expectantly with watchful waiting are re-evaluated annually.

Conservative & Interventional Treatment:

In general, medical therapy is offered as first-line management for patients with moderate to severe symptoms of BPH who do not require surgery.7 An alpha-blocker is considered as initial therapy for most patients and a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor can be added for those patients at risk of progression.7 Patients are evaluated 4 to 12 weeks after starting medical therapy. Patients need to be assessed using the IPSS; further evaluation may include a post-void residual (PVR) and uroflowmetry. Modification in treatment is required where patients do not show improvement in symptoms and/or experience intolerable side effects.

Interventional therapy (e.g., Transurethral resection of prostate [TURP]) – For patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS and those who have developed acute urinary retention, or other complications of BPH. TURP is accepted as the criterion standard for relieving bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) secondary to BPH.11 In current clinical practice, most patients with BPH do not present with obvious surgical indications; instead, they often have milder lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and, therefore, are initially treated with medical therapy. Several minimally invasive treatments for BOO are also available.

Counselling & patient education play important role in determining intervention, which can include behavioural/lifestyle modifications, medical therapy, and/or surgical options.

Summary:

BPH is hyperplasia of both epithelial and stromal prostatic components. A key characteristic of BPH is increased stromal: epithelial ratio. Prostatic hyperplasia can eventually result in bladder outlet obstruction. Obstruction has both a static component due to increased volume of tissue, particularly in a transition zone, and a dynamic component due to increases in stromal smooth muscle tone. A large number of alpha-adrenergic receptors are present in the prostate capsule, stroma, and the bladder neck. The predominant alpha-1 receptor in prostatic stromal tissue is the alpha-1A receptor. Treatment of symptomatic BPH is mainly accomplished through relaxation of smooth muscle tone with alphablockers and the reduction of the size of the glandular component following inhibition of the formation of dihydrotestosterone by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Select surgical intervention (e.g., transurethral resection) alleviate symptoms of urinary obstruction by reduction of prostatic bulk.12

References:

Image 1: IPSS Score - Mild score: 0 to 7; Moderate score: 8 to 19; Severe score: 20 to 35

1. Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, et al.

The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984 Sep;132(3):474-9. 2. Lee SW, Chan EM, Lai YK. The global burden of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017 Aug 11;7(1):7984. 3. D'Ancona C, Haylen B, Oelke M, et al.

The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019

Feb;38(2):433-77. 4. Masumori N, Tsukamoto T, Kumamoto

Y, et al. Japanese men have smaller prostate volumes but comparable urinary flow rates relative to American men: results of community-based studies in 2 countries. J Urol. 1996

Apr;155(4):1324-7. 5. Isaacs JT, Coffey DS. Etiology and disease process of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 1989;15(S2):3350. 6. Nickel JC, Aaron L, Barkin J, et al.

Canadian Urological Association guideline on male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (MLUTS/BPH): 2018 update. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018

Oct;12(10):303-12. 7. Lerner LB, McVary KT, Barry MJ et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline. 2021 [internet publication]. 8. Bartsch G, Fitzpatrick JM, Schalken

JA et al. BJU Int 2004; 93 Suppl 1: 279. Roehrborn CG, McConnell J, Bonilla J et al. J Urol 2000; 163: 13-20. 10. Hewitson P, Austoker J. BJU Int 2005; 95 Suppl 3: 16-32 11. [Guideline] Parsons JK, Dahm

P, Köhler TS, Lerner LB, Wilt TJ.

Surgical Management of Lower

Urinary Tract Symptoms Attributed to

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: AUA

Guideline Amendment 2020. J Urol. 2020 Oct. 204 (4):799-804. 12. Patel AK, Chapple CR. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: treatment in primary care. BMJ. 2006 Sep 9;333(7567):535-9.

NEWS - EMA adopts first list of critical medicines

On 7 June 2022, EMA’s Medicines Shortages Steering Group (MSSG) adopted the list of critical medicines for the COVID-19 public health emergency. The medicines included in the list are authorised for COVID-19 and their supply and demand will be closely monitored to identify and manage potential or actual shortages. Given the current stage of the pandemic, the published list contains all the approved vaccines and therapeutics in the European Union (EU) to prevent or treat COVID-19. It will be updated to reflect changes in the pandemic situation which may give rise to an increased risk of shortages of particular medicines, or following the authorisation of new medicines. The list does not replace national guidance on vaccination and the clinical management of COVID-19.

Marketing authorisation holders (MAHs) of medicines included in the list are required to regularly update EMA with relevant information, including data on potential or actual shortages and available stocks, forecasts of supply and demand. In addition, Member States will provide regular reports on estimated demand for critical medicines at national level. This will enable the MSSG to recommend and coordinate appropriate EU-level actions to the European Commission and EU Member States in order to prevent or mitigate potential or actual shortages of critical medicines to safeguard public health.

The MSSG was recently established under Regulation (EU) 2022/123, which assigns a reinforced role to the Agency in crisis preparedness and management for medicines and medical devices to monitor shortages and ensure a robust response to major events or public health emergencies, and to coordinate urgent actions on the supply of medicines within the EU.

An Update on the Diagnosis and Management of COPD

Written by P.C. Ridge; S.M. Walsh Department of Respiratory Medicine, University Hospital Galway, Ireland | National University of Ireland, Galway Correspondence: Dr Padraic Ridge, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Galway University Hospitals, Galway, Ireland E mail: p.macaniomaire1@gmail.com

Dr Padraic Ridge

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common condition characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms with non-variable airways disease (obstruction) and/or alveolar damage (emphysema). It is caused by significant exposure to noxious gases or particles.1 In this article, we review the disease pathogenesis, epidemiology, approach to assessment, diagnosis and chronic disease management for a patient.

Pathogenesis

Cigarette smoke is the most common risk factor for COPD worldwide, accounting for approximately 80% of cases. Pipe tobacco and marijuana are other risk factors.1 Passive exposure to cigarette smoke can also lead to COPD by increasing the total burden of inhaled particles and gases that the lungs are exposed to. Other causes include burning of biomass fuels, air pollution and occupational exposures, including those experienced by sculptors and gardeners.2 Interestingly, not all individuals who smoke will develop COPD. Even in those who are heavy smokers, less than 50% will develop COPD during their lifetime.3 This variability is believed to be due to a complex interplay between the type and intensity of noxious exposures and individual factors such as genetics, age, gender, airway hyper-responsiveness, infections and overall lung development in childhood.1, 4, 5

Epidemiology

The prevalence of COPD is increasing worldwide and is expected to continue to rise due to ongoing exposure to COPD risk factors, particularly smoking, in developing countries and an aging population in developed countries.3, 6 The global burden of disease study reported COPD as the third leading cause of death worldwide.7 The estimated worldwide COPD mean prevalence is 13.1%, however data in many geographic areas is scarce.4, 6

Dr Sinead Walsh

Assessment of a patient with suspected COPD

The three main symptoms of COPD are dyspnoea, chronic cough, and sputum production. The first and most common symptom reported by patients is dyspnoea on exertion. Less commonly, patients describe symptoms of wheeze, fatigue and anorexia. The key findings on clinical examination of a patient with COPD are usually absent until significant impairment of lung function has occurred.8 Tachypnoea occurs with activity, with increasing respiratory rate in proportion to disease severity. Use of References accessory respiratory muscles and paradoxical indrawing of the available on request lower intercostal spaces (Hoover sign) indicates airway hyperinflation and a flattened diaphragm. Other findings on thoracic examination include a barrel chest, hyperresonance on percussion, diffusely decreased breath sounds, and prolonged expiration.

Diagnosis and staging

Diagnosis of COPD is based on a triad of causative exposure, FIGURE 1: symptoms and spirometry. Spirometry is the most reproducible and objective measurement of airflow limitation.1 It measures the volume of air that a patient can forcibly exhale from the point of maximal inspiration (forced vital capacity, FVC) and the volume of air that is exhaled during the first second of this manoeuvre (forced expiratory volume in one second, FEV1). The ratio of the FEV1/FVC is calculated. Airflow obstruction is a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio less than 70%. At diagnosis patients should have the severity of their airflow limitation classified according to the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) guidelines. This classifies patients with a FEV1/ FVC ratio less than 70% into four categories (GOLD 1 – 4), based on their FEV1 value (FIGURE 1). Symptom burden should be assessed using the mMRC (Modified British Medical Research Council questionnaire) or the CAT (COPD Assessment test). An assessment of exacerbation risk should also occur. A COPD exacerbation is an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that results in additional therapy.9 Exacerbations can be classified as mild, moderate or severe. The best predictor of having frequent exacerbations (defined as two or more exacerbations in one year) is a history of previous exacerbations.10 Using these variable individuals may be classified as GOLD A – D1

Figure 2

(FIGURE 1). This classification system divides individuals into phenotypes of those who are relatively asymptomatic (A), symptomatic on a daily basis (B), have regular exacerbations but are asymptomatic in between episodes (C) and those who are symptomatic on a daily basis and suffer relatively frequent acute exacerbation of their symptoms requiring oral steroids (D). This phenotypic subdivision of individuals into those who are breathless or who exacerbate frequently allows more targeted therapy. Typically those who are breathless benefit from bronchodilator therapy and those who suffer frequent exacerbations benefit from anti-inflammatory treatment1 (FIGURE 2). In our practice we obtain a chest radiograph in all new suspected COPD patients. While it does not diagnose COPD, it can be useful at excluding alternative diagnoses and establishing the presence of comorbidities including pulmonary fibrosis, pleural disease, kyphoscoliosis and cardiomegaly. We obtain routine laboratory investigations, including FBC to check for eosinophilia. We screen for alpha one antitrypsin deficiency in concordance with WHO recommendations.11 For those with recurring exacerbations we check an immunoglobulin level to screen for hypogammaglobinaemia.

MANAGEMENT

1.Smoking Cessation

The cornerstone of treatment for COPD is smoking cessation and must be stressed with those who continue to smoke at every encounter.1 Individuals should be offered both non-pharmacological and pharmacological (nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline etc.) assistance to quit.1 Unfortunately, COPD is invariably a progressive disease as damaged lung is unrecoverable and lung function will continue to decline with age regardless of smoking status. However if individuals continue to smoke lung function will decline much more rapidly and ultimately result in a much higher symptom burden at a much earlier stage.12 Electronic cigarettes (e cigarettes/ vaping) have increased in popularity as an alternative to cigarettes. In addition to nicotine, they can contain other chemicals, the long-term health effects of which are largely unknown.1 However, they have been associated with vaping-associated lung injury, alveolar haemorrhage and death.1 E-cigarette use is increasing among Irish teenagers.13 There is a perception that e-cigarettes may be healthier than cigarettes in this age group. There is a lack of information about e-cigarettes from school education programmes on smoking.13

2.Bronchodilator therapy

Dyspnoea is multi-factorial in COPD. Contributing factors include: • Airway obstruction • Parenchymal destruction • Dynamic hyper-inflation leading to air trapping, small airways collapse and negative effect on compliance resulting in increased work of breathing and subjective shortness of breath (SOB)14 • Systemic effects of COPD including sarcopenia15 Bronchodilators address the airways obstruction, altering airway smooth muscle tone, leading to widening of the airways and improving dynamic hyperinflation. Available inhalers include short acting and long acting beta agonists (SABA/LABA) and muscarinic antagonists (SAMA/ LAMA). These therapies have been shown to improve dyspnoea, improve exercise performance and reduce the frequency of exacerbations. In asthma, LABA monotherapy (without an inhaled corticosteroid) is associated with an increased mortality. This is not the case with COPD where monotherapy is safe1 (FIGURE 2). Combination bronchodilator therapy of a LABA and a LAMA in a single inhaler demonstrate improved patient reported outcomes, compared to monotherapies alone,with improved quality of life demonstrated.1

FIGURE 3:

3.Anti-inflammatory

Exacerbations in COPD are predominantly due to viral infections and airway inflammation. Therefore anti-inflammatory therapies form a cornerstone in COPD therapy for those who are frequent exacerbators.

Inhaled Corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in combination with LABA therapy are useful for dampening airway inflammation, thereby reducing exacerbation frequency. They also have a positive effect on lung function and dyspnoea.1 There is an ever growing body of evidence that eosinophilia is a useful biomarker for predicting a positive response to ICS therapy.16 While ICS therapy has been shown to reduce exacerbations and improve symptoms, they have been associated with a slight increase in pneumonia, especially in those with eosinophils <0.3u/L and more severe disease. We therefore consider ICS therapy in those with two or more exacerbations per year, eosinophils ≥0.3u/L or a history of asthma/atopy.1, 11, 17

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic. It has antimicrobial effects but also has an anti inflammatory effect in the airway and interferes with biofilm formation. It can be added on to therapy in former smokers who continue to exacerbate despite maximal inhaled therapy. It is recommended to be continued for one year but in practice individuals remain on it for much longer due to its’ exacerbation lowering effects.1 Prior to initiating therapy, sputum samples should be checked, and non-tuberculous mycobacterial colonisation should be excluded as this is a contra-indication to therapy. As it can cause QT prolongation, an ECG should be performed prior to initiating therapy and one month post initiating therapy. Patients should be counselled to monitor for signs of ototoxicity, palpitations and diarrhoea.18 Data is limited in those who are active smokers.19

Roflumilast

Roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor and works by reducing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). It reduces inflammation in the airway but has no immediate bronchodilator effect. It may be a reasonable add-on therapy in selected patients with a chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD with severe airflow obstruction and a history of exacerbations. In some individuals, roflumilast may be intolerable as it can be associated with severe, nausea, headaches, diarrhoea and weight loss.20 We avoid starting this treatment in those with a low body mass index. Roflumilast is not approved for reimbursement under the community drug schemes in Ireland.

4.Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to be of tremendous benefit in patients with COPD. It improves dyspnoea and quality of life. In those discharged from hospital, pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the re-admission rate by approximately 50%.21 - 23 It is recommended for GOLD B-D patients and for those discharged from hospital with an exacerbation of COPD (ideally within 4 weeks of discharge)1 Pulmonary rehabilitation consists of an 8-12 week course consisting of a supervised incremental physiotherapy program where patients build up their muscle

strength. Patients also receive education regarding their condition, lifestyle advise, dietetic input (if required) and are taught breathing exercises and the benefit of pacing.24 Interestingly while pulmonary rehabilitation improves dyspnoea it has no direct effect on lung function. COPD is a systemic disease resulting in inefficient sarcopenic muscles. Pulmonary rehab works by increasing aerobic fitness, reducing lactic acidosis production and thus breathlessness.15

5.Long Term Oxygen Therapy (LTOT), Ambulatory Oxygen Therapy (AOT) and Non-invasive Ventilation (NIV)

LTOT is indicated in the following scenarios:25

1. PaO2 ≤7.3kPa (3 weeks apart) 2. PaO2 ≥7.3kPa to ≤8kPa with pulmonary hypertension, pedal oedema or raised haematocrit

3. Palliative reasons

Ambulatory oxygen is indicated in those who:26

1. Are on LTOT and are active outside the house (to help them get the required 15 hours per day) 2. Significantly desaturate on exertion and can walk further with the use of AOT

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is indicated in those who:25, 27

1. Demonstrate symptomatic hypercapnia (headache, confusion, lethargy) 2. Are post hospitalisation if

PaCO2 is persistently raised28 3. Require LTOT but develop hypercapnia from same

6.Other interventions

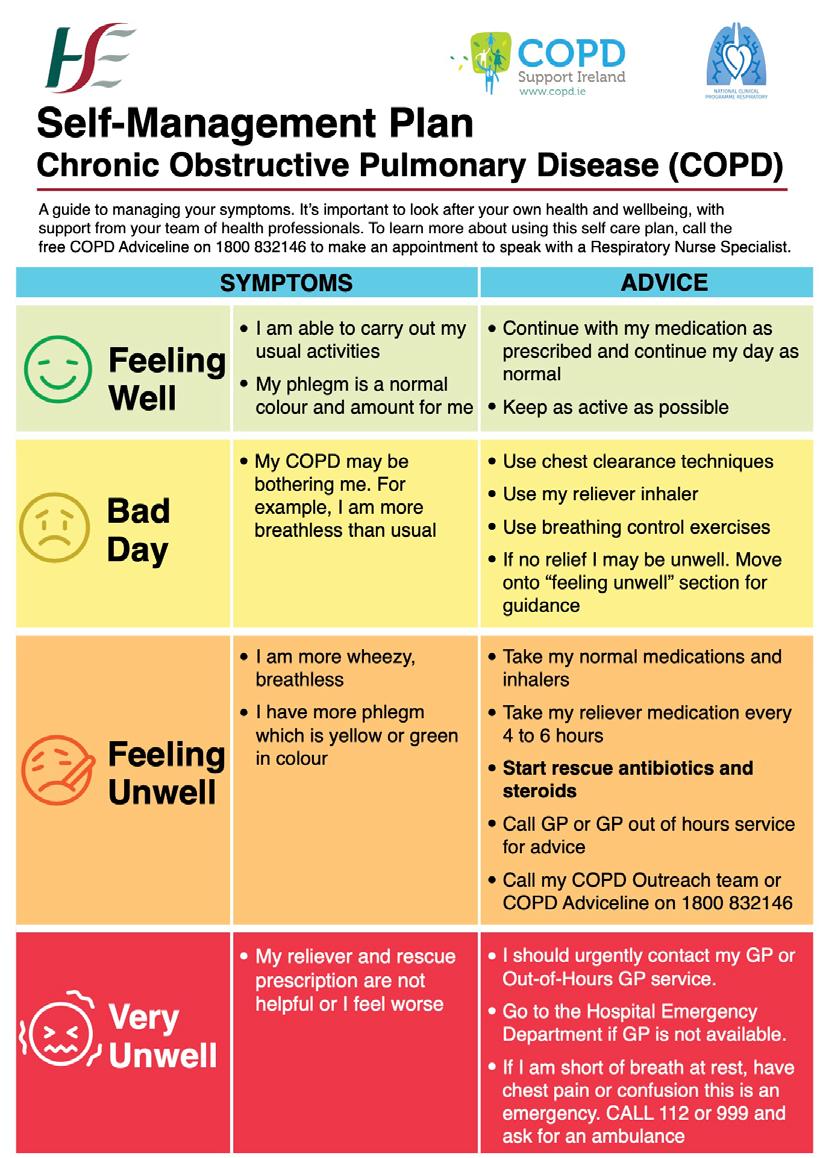

Vaccination against Influenza virus, Pneumococcus and SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) are recommended by GOLD.1 Vaccination reduces serious illness, exacerbations and mortality in COPD patients. COPD is associated with a number of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, skeletal muscle dysfunction, osteoporosis, gastro-oesophageal reflux, sinus disease, anxiety, depression and lung cancer.1 These comorbidities influence mortality and hospitalisations in a patient with COPD. Therefore, they should be sought for and treated appropriately.1 In very severe COPD, palliative care input should be sought to aid with refractory dyspnoea.1 COPD Support Ireland is Ireland’s national support and advocacy body for people affected by COPD. By providing patients with knowledge of their condition, how to take their inhalers, how to control the sensation of breathlessness, it enables patients to live well with COPD. There are local COPD support groups throughout Ireland, providing regular exercise classes. Every patient should have a selfmanagement plan for their COPD (FIGURE 3).

7.Surgery and bronchoscopic interventions

In those with predominantly upper lobe emphysematous disease or bullous disease there are surgical options to help with dyspnoea. This can be done surgically through bullectomy or lung volume reduction surgery. Here the dead space or area of wasted ventilation is removed. This allows the healthier, compressed lung to re-expand and contribute more to ventilation.29 The same effect can achieved bronchoscopically by blocking off the ineffectual lung endoscopically, leading to its’ collapse allowing the more effective lung to re-expand.1 Those with very severe COPD who are deemed fit should be referred for lung transplantation assessment.1

Conclusion

COPD is a prevalent disease with a high disease burden. Management focuses predominantly on early diagnosis, improving symptoms of shortness of breath and reducing exacerbations for which we have a growing armament of treatment options.

References available on request

Figure 3

Informing Genetic Disease Research

A new study by RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences examining population genetics across Europe has analysed the diverse ancestries of people living in the UK. This knowledge has the potential to inform future health research on genetic factors leading to disease.

The study, led by researchers at the RCSI School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences and the SFI FutureNeuro Research Centre, has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The RCSI and FutureNeuro researchers used the UK Biobank, a database of genetic and health information of over 500,000 participants from the UK, to examine population genetics and ancestry across Europe. The study analysed the genetic ancestry data of individuals in the UK Biobank who reported having a European birthplace outside of the UK – about 1% of the dataset. Researchers catalogued where individuals shared segments of their genome with other individuals, meaning they had a common ancestor within the past 3,000 years.

With this information, the researchers could group individuals with more segments in common than on average into three branches, corresponding to southern, central-eastern, and northwestern Europe.

By studying the patterns of the genome sharing, the researchers were able to infer historical patterns such as population size and how genetically isolated specific European regions are, relative to each other. In general, people from southern Europe were found to have less in common genetically with each other than in other areas, due to the larger population sizes and therefore usually greater number of ancestors in the region.

An exception to this was Malta which, being an island, was found to have a smaller pool of ancestors. This is the first large sample analysis of Maltese population genetics. Identifying European regions such as Malta with specific histories of genetic isolation could potentially aid the discovery of genetic factors contributing to disease.

In addition to building and expanding upon previous knowledge in Europe, the results present the UK Biobank as a source of diverse ancestries beyond the UK. This has the potential to complement and inform researchers interested in specific communities or regions across Europe and the world.

Professor Gianpiero Cavalleri, Professor of Human Genetics at RCSI, Deputy Director of FutureNeuro and senior author on the paper, commented: “This research has shown the diversity of European ancestries sampled by the UK Biobank and has enabled us show the “big picture” of the genetic landscape of Europe, including new insights into communities such as within Malta. This work suggests similar gains of knowledge could be found within non-European ancestry groups using the UK Biobank, groups that are typically excluded from genetic analyses.”

Two new replacement orthopaedic operating theatres on the Merlin Park site, which cost ¤10.57m to design, build and equip, were used for the first time last month.

Prior to the opening of the new theatres, there was only one orthopaedic theatre on the Merlin Park site. This was the only facility available in Galway University Hospitals (GUH) to provide elective orthopaedic procedures. The two new replacement theatres are required to restore full elective orthopaedic procedures in Merlin Park University Hospital and address orthopaedic waiting lists. Construction of the 620m2 theatre building began in March 2021 following a public procurement tendering for a main contractor. The build consists of two operating theatres, two anaesthesia rooms, a recovery area and other ancillary accommodation to support the theatre suites. The theatre building is connected to the main hospital block by a link corridor which is the access point for patients and staff. The hospital has been providing 10 theatre sessions per week; this will increase to 20 sessions per week when two fully functional theatres are in place which will enable approximately 4,000 procedures per annum to be carried out. Demand for orthopaedic services is increasing year on year as is the complexity and sub specialisation within orthopaedic surgery. GUH is currently recruiting staff to increase the number of theatre sessions to 20 per week and will also be seeking funding to staff the old theatre in 2023 to assist in providing further capacity. Mr Aiden Devitt, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon said, “The new operating theatres are a major

Mary Keane, Clinical Nurse Manager 2 and Mr John Galbraith, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon

enhancement for the hospital and for orthopaedic services in the west and I am extremely proud of everyone involved in bringing this long-awaited project to completion. We now have a state of the art theatre suite which will double our capacity for surgical procedures and will reduce waiting times for patients. Our orthopaedic patients will be treated in a modern, spacious and technologically advanced facility and I am delighted to be commencing procedures in the new theatres this week.” Ms Chris Kane, Hospital Manager said, “This is a significant investment in healthcare infrastructure for the people living along the western seaboard who come to Galway for their surgery. The theatres have been built and equipped to a very high specification to enable us to deliver the best possible care to our patients. “We look forward to resuming a full elective orthopaedic surgery service in Merlin Park University Hospital.