A RT

40TH-ANNIVERSARY VAE GALA

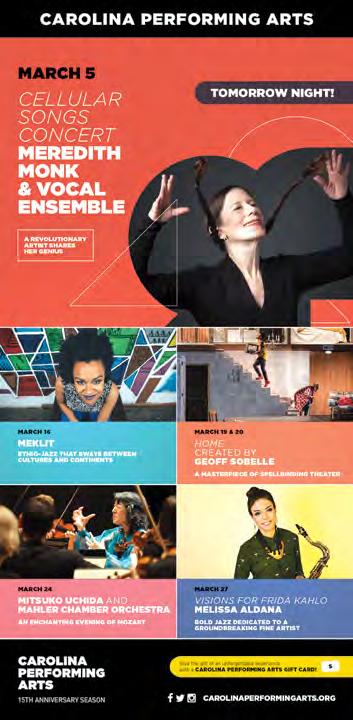

Saturday, Mar. 7, 6:30–11 p.m. | $65–$150 | Dorton Arena, Raleigh

A performer from Imagine Circus in front of Nate Sheaffer’s neon art piece at VAE Raleigh’s 2019 gala PHOTO BY DAN HACKER/COURTESY OF VAE RALEIGH

er than trying to be everything to everyone. We began to focus on socially engaged art, which we see as contributing to positive change in the community. That’s where we are now.

Jumpstarting Art After helping a generation of artists express themselves, VAE Raleigh turns 40 with a sharpened focus on social justice BY EMILY CATANEO arts@indyweek.com

I

n 1980, Raleigh artists Margot Richter, Bob Rankin, Barbara Burnham, and Marriott Little noticed a problem: There were no local resources for nascent creators to get their feet in the door of the art world. So they started a small group to help aspiring painters and sculptors begin their careers. Four decades later, that idea has grown into a venerable cultural-arts nonprofit on West Martin Street. VAE Raleigh, which is celebrating its 40th birthday with a fundraising gala at Dorton Arena on March 7, has been many things to many people: an exhibition space for first-time artists, a place to learn professional skills, and a powerful ally of socially engaged art. It’s been the force behind SparkCon, Raleigh’s annual pan-arts festival; the host of a queer homecoming and many other kinds of gatherings; and an exhibitor of everything from poetry to painting, neon signs to giant spray-foam ducks. The INDY sat down with executive director Brandon Cordrey to discuss the phases of VAE’s history, its efforts to combat the entrenched discrimination of the art world, and more. 36

March 4, 2020

INDYweek.com

INDY: What were those original artists trying to achieve? How have you fulfilled that mission? BRANDON CORDREY: In 1980, there were four private galleries and great museums [in Raleigh] but no other space for artists to get their start. Artsplosure, the cultural-events production studio, was also founded in 1980, but N.C. State’s Art United didn’t exist, and neither did the United Arts Council, the funding wing of the county. Even the culture of hanging art in coffeeshops wasn’t as prominent as it is now. So those artists created an accessible space, flexible enough for new artists to fail and get better until they got the experience needed to rise to the gallery level. For a significant period, VAE was about accessibility for new artists. Then they hired Sarah Powers as director and began to focus on professional skills. Then came Google, and all that information became accessible on the internet. So around 2015, we began to do more work around socially engaged art. We looked around, and the art community had expanded so much around us. That allowed us the opportunity to curate ourselves, to focus on one particular part of art, rath-

How have issues around equity in the arts evolved since 1980? How has VAE fought for equity in the arts? The cultural arts have a strong foundation in racial oppression and segregation. The arts community has begun to look that in its face and figure out ways to rectify it, but we don’t see a lot of diversity at the very highest levels of arts organizations. We’re still trying to achieve that real equity. Five years ago, our board was 86 percent white. Now it’s 44 percent white, which is much more reflective of the artists we’re working with and the community we serve. We’ve also tried to change our physical space. We try to write text on the wall that’s readable and solicits feedback; we believe that your interaction with this work and with us is the only way that the work is fully itself. We often play music so it’s not a quiet white box and paint the gallery so it’s actually not a white box. And we have gallery guides who will ask questions. Like for our current exhibit, The Full Light of Day, which showcases the work of artists with disabilities, we ask, how many people with disabilities do you know? If you’ve used words like “retarded” or “wheelchair-bound,” how do you think the artists in this exhibition would feel about that? How do you feel about that? There’s no wrong answer. Our space is also fully physically accessible. If someone who’s blind or low-vision comes into a quiet gallery—why would they want to do that? We recently had an audio-described and tactile tour, where we had the Wake Federation for the Blind come through, feel things, and have conversations about the art. One notable aspect of VAE is how interdisciplinary you all seem to be. If creating social change is your end goal, then you’re much less likely to focus on your own particular medium, and you’re more likely to focus on what will ultimately get you to your goal. With our current project, there’s a lot of visual art in the space, but there’s also redacted literary work, and there’s an artist who came in to do a performance piece that expanded on their visual art piece, which is all found objects.