6 minute read

This world of mine

Hawakal Publishers, New Delhi, Calcutta, 2021, ISBN:978-81952401-5-9, Paperback, INR 350 A Review by Swati Pal Don’t be deceived by the seemingly simple words in this selection of poems by GJV Prasad. This world of mine is his latest collection of poems, some old, some published earlier and some new, put together in a slim volume by Hawakal Publishers. Each word will cut into your consciousness and before you know it, you will find yourself pensive, thoughtful, laughing and crying- all at the same time. Perhaps that’s what GJV’s world and ours makes us do; it is after all a shared world but with the difference that not all of us can make poetry out of it as GJV has done.

It is difficult to put a label upon GJV as a writer. Is he a feminist? A number of his poems look at the myriad challenges faced by women whether they be those in myths or those outside; indeed he makes one think that there is perhaps no difference between myth and reality as the questions remain the same for all. The three Sati poems as also Draupadi and Hey Ram speak for and appear to be insights by women of all times. They are incisive about the rituals we practice, the almost celebratory and even commercial nature of these rites that make a mockery of how in reality we treat women. The words and the images evoked in these poems are often dark, compelling and disturbing. The almost tongue in cheek and yet equally unsettling poem Edible Women where women are referred to as delectable consumer items are an uncomfortable reminder of the way in which women are spoken of and represented in media in particular but even in common parlance. We realize that society has internalized such references so that they cease to shock us when we encounter them. But when GJV says, I mean to say I can snack/On you any time/And time and again, you are jolted out of your comfort zone. This, despite the almost droll ending: My jangiri my halwa/My burfi my desi ghee/Besan laddoo.

Advertisement

Whether we label him a feminist or not, these poems, as others, reflect on GJV’s deep concern with perception, in particular with the way that women are perceived. Take a poem like WhatsAppery which is a close to the bone comment on whatsapp groups where debates and discussions are often indicative of the chauvinism that seems to be so endemic in society. Statements like You will say so, you are a woman/ we have seen how women exploit the laws or again, The fact is that women/Have filed false dowry cases/Have accused men of rape/If a relationship doesn’t end in marriage/ The laws are so skewed/We men walk around in fear may seem laconically written but are obviously meant to make us revisit the way we perceive and refer to men and women, often filled with self righteous indignation. GJV gently makes fun of this misplaced indignation.

How does GJV see India? Is he a nationalist? What is his political vision? Is he a humanist?

Several poems from the opening Desperately seeking India to the two 15th August poems , Partitions, Godhra- Gujarat, Gujarat 2005, 31st October 1984 and Election Strategies: Shining India give the reader some idea about what fascinates, maddens, saddens and infuriates the poet about India and Indian politics. His x ray vision pierces through superficial trappings to deconstruct political happenings and events. While each of these poems narrates a different aspect of the political machinations that drive the country one way or the other, the lines that best express the plight of the nation are in the poem 15th August 1974 where the poet says we fought for light/ we got it/ we didn’t know/ what to make of it and the next stanza is almost a lament, an elegy, in darkness/there was hope/ in light/ there is despair. Indeed, it is 75 years since the country attained Independence from colonial rule and while much has changed, so much remains to be done that ‘despair’ quickens the pulse. It is really interesting how GJV can use a line from a comic book series The phantom never dies/ Old jungle saying to capture the essence of the spectre of death through violence that rears its ugly head in collective memory. Indeed GJV can use the most mundane and commonplace of phrases and fashion them in such a way that a whole new meaning unravels. That is one of the many linguistic tricks that you are treated to in his poetry.

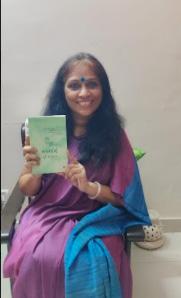

Dr Swati Pal

One label that GJV wears on his sleeve is of course clear; that of an academic and a JNUite. How Brown Was My Campus, JNU, First Class In Room 016 and Two writers at JNU are the poems that make his love, concern and his nostalgia for JNU very clear. It is a known fact that GJV is the stuff that legendary academics are made of; loved and admired by generations of students at JNU for many of whom, JNU and GJV are almost synonyms. Old timers from JNU will certainly find that these poems mirror their own fondness and fears for an institution they see as pivotal to the formation of their identities. And another label that can easily be attributed to GJV is that of the family man or rather as one for whom the family and its individual members play a big role. A picture emerges in the eyes of the reader of various members of the poet’s family, his father, his brother and his nephew.

However,the fact is that GJV and his poetry defy labels, though the subconscious mind tends to attach one or the other, as this reviewer attempted. So, perhaps the best way to find out what his poetry means would be to read him. That is a pun.

Can one read another? That too, through poetry?

Perhaps GJV says it all:

Why does poetry make so much sense to me

When I never knew what the poets mean

Why does poetry give me so much energy

When it takes so much effort to read

Prof. GJV Prasad

Swati Pal, Professor and Principal, Janki Devi Memorial College(DU) has been an educator since the last twenty seven years. She also translates and writes poetry.