6 minute read

The history of Ind V Aus

from 2019-03/04 Brisbane

by Indian Link

Sydney-based historian Kersi Meher-Homji on the highlights, as well as the less documented moments, of a 70-year relationship

BY RITAM MITRA

As India and Australia conclude yet another bilateral series – just a mere two months after the end of India’s historic tour Down Under – it’s easy to forget that the countries have not always been such familiar foes.

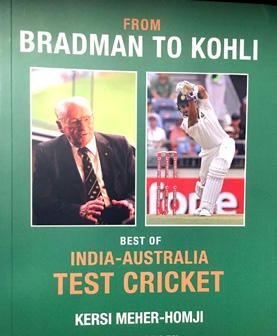

From Bradman to Kohli, the latest book penned by renowned cricket historian Kersi Meher-Homji, explores the vagaries of the relationship between perhaps the two most dominant forces in world cricket over the last 20 years, recounting in detail the most memorable (and some forgotten) moments in what has recently become, but has by no means always been, cricket’s premier rivalry.

India and Australia did not play their first Test match against each other until 1947, with India’s 1932 emergence as a Test nation halted throughout World War II. It was an enormous mismatch; India, in every respect a juvenile in world cricket, was roundly thrashed by an innings and 226 runs in Brisbane as Bradman’s Australians, who would later that year be anointed as the Invincibles in a legendary tour of England, ran rampant. Much like Warne’s unremarkable figures of 1-150 in his debut Test against India in 1992, so too was India’s introduction to Australia less than promising.

From Bradman to Kohli is perhaps the most complete record of the Test matches played between the two nations since that 1947-48 tour, a contest which has since 1996 been known as, and has been played for, the Border-Gavaskar Trophy. Most cricket fans today - age permitting - will remember the more recent contests chronicled in the book, particularly those played in the digital information age. But it is those less documented moments recounted by Meher-Homji, which unfolded before the advent of not only television, but well before transistor radios, which particularly capture the imagination and evoke nostalgic intrigue.

The majority of cricket followers are familiar with one of cricket’s most debated rules, officially known in the MCC laws as “Non-striker leaving the crease early”, but in every other context, referred to as the ‘Mankad rule’, after Indian bowler Vinoo Mankad infamously ran out Australia’s Bill Brown in this manner at the SCG during India’s debut tour of Australia. What is not as widely recalled about that incident was it was the fourth time on the tour that Brown had either been warned or actually run out by Mankad in this manner. In a previous tour game at the SCG, Mankad had warned and subsequently run Brown out at the non- striker’s end, while in the next tour match against Queensland, Mankad had once again warned Brown when he strayed too far from the crease.

Mankading is still seen as an unsportsmanlike act today, despite being encoded in the laws of the game. Yet as Meher-Homji notes, at the time, many, including Bradman, suggested that Brown should have learned from his earlier mistakes. Meher-Homji quotes Bradman’s comments in his 1950 autobiography

Farewell to Cricket: “Mankad was an ideal type, and he was so scrupulously fair that he first of all warned Brown before taking any action. There was absolutely no feeling in the matter as far as we were concerned, for we considered it quite a legitimate part of the game”.

Often lost too, to the annals of history, are the intricacies of touring life that are no longer part of today’s game, whether for better or for worse. In 1935-36 and 1945, for instance, Australia sent a number of “unofficial” Australian representative sides to India, including a mixture of retired ex-players well into their 40s as well as emerging talents. Forgotten too, given the current trends of entering Test series with barely a warm-up match in sight, is that in the pre-Packer days, touring teams would play all states before their first Test, as did India in its maiden tour of 1947-48. On the other side of the coin, it’s only in the second half of India’s relationship with Australia that Australian players stopped dreading tours of the subcontinent. Until the 1970s, touring India meant the very real risk of gastroenteritis, sub-standard accommodation and inhospitable conditions. In fact, some Australian players even came close to dying from their afflictions – just ask Gordon Rorke, who fell so ill in 1959-60, he never played another Test, but would have felt lucky just to survive.

More than anything though, MeherHomji’s book is a reminder of the rich and storied history of India-Australia Test cricket, and how far both countries have come since they first faced off some 70 years ago. Although it is India’s identity in particular that has changed most markedly, it is not too far a stretch to say that the valiant efforts of the likes of Hazare, Tiger Pataudi, Bedi and Gavaskar, played no small role in paving the way to India’s historic triumph in Australia this summer.

US-based Indian-origin writer Sohaila Abdulali talks about personal experience, her research and her professional experience at a rape crisis centre

BY APARNA ANANTHUNI

We need to talk about rape. Or rather, what rape is, and what it is not. This is what struck me most, listening to Sohaila Abdulali speak at Melbourne’s Wheeler Centre about her new book, What We Talk About When We Talk About Rape – what she called her “manifesto for living”. Abdulali was confident, humorous, and strident as she spoke about rape, as a survivor, as someone who has gone on to have a “great life”, and as someone who also decided she still had more to say, some thirty years later.

I walked away from her with the most unexpected feeling: lightness.

Because what we normally do is circle rape, warily. We treat it like a rare, poisonous flower. We treat it like a spectre. We treat it like shame so intense it should kill you. We treat it like Lord Voldemort: He Who Must Not Be Named.

Abdulali, instead, got right up in rape’s face, and said ‘I know you, I know what you are.’

So, ladies and gentleman – well, mostly gentleman, let’s be honest – let me tell you a few things about rape…

Rape is not sex, but we have to talk about sex when we talk about rape

Why do those who have been raped so often feel shame at being raped, something that can’t really be said of any other crime?

“I think it’s partly…the confusion of rape and sex,” Abdulali said. “As people and society we have a lot of shame about sex.” As a sexual act, then, rape makes us “ashamed and weirded out and uncomfortable.”

So, sex education is absolutely key. “If we’re teaching sex education or sex ethics to boys and girls in such a way that they come to regard sex as something men can take, and men can enjoy, and women, it’s really for them to just put up with …then we’re really encouraging rape.”

Rape is a choice, not a character trait

There’s a short, clear answer to the question of ‘what causes rape’ and Abdulali gave it unapologetically: “Men!”

And it’s completely, undeniably true – it’s almost always men who are the perpetrators of rape.

But no, it’s not a ‘certain type’ of man, as so many of us would like to believe.

Because the terrifying, sobering fact is that men who rape aren’t the ogres from fairytales, or the monsters under the bed. They are as human as you or I. They make a choice. As Abdulali quipped in response to those who worry about the demonisation of ‘poor innocent men’ through movements like #MeToo: “I don’t know where these innocent men are!”

“Who are these men? They’re regular guys, they’re regular husbands and fathers,” she said. “I wish I could say, ‘these men are different’. I think it’s a potential in everyone, a choice everyone could make. And many don’t.”

Rape is like any other crime and yet it’s not Rape is complicated. “It’s a crime like any other crime, and yet it’s not; it’s unique - every crime is unique,” Abdulali mused. “Rape is not more unique than other unique crimes.” The difference is that rape is forcibly entangled with so many other things: “It’s so tied up in our minds with honour and shame and blah and sex and being spoilt,” Abdulali said. It’s also, as she pointed out, “the one crime that we judge according to how the victim reacts.”

Rape shouldn’t be put in a separate box to other traumatic physical crimes. “By bringing it into the realm of terrible traumas like other terrible traumas you’re not diminishing it or say it’s less; you’re just saying, it’s as manageable or not as other things.”

To stop rape, you need to dismantle patriarchy

Rape is entrenched in behaviours and attitudes: it’s not outside society, it’s right in the thick of it.

“What are we talking about, with rape?” Abdulali asked. “We’re talking about an entire culture of a way that men treat women, and then we all treat each other.”

Rape will continue as long as we are, as she so nicely put it, “mesmerised by patriarchy.”