2 minute read

Sweat soaked saris: Dance disclosures A daring book reveals the unacknowledged influence of Indian classical dance into America’s modern genre

from 2012-09 Sydney (1)

by Indian Link

of South Asian communities in the US, and their location within the US multicultural discourse.

BY CHITRA SUDARSHAn

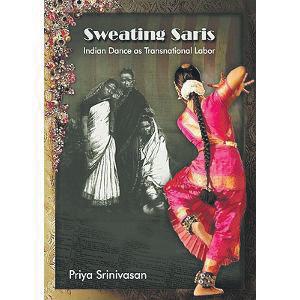

In her ground-breaking work, Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor (December 30, 2011) Priya Srinivasan examines dancers not just as aesthetic bodies, but as transnational migrant workers and wage earners who negotiate citizenship and gender issues.

Sweating Saris seeks to understand dance – and more specifically, Bharatanatyam – as gendered bodily labour, and through it, highlights racism and a certain cultural bias inherent in the idea of American citizenship. The author argues that by examining the Indian-American dancing woman as a labourer, one can see her negotiating the terms of US citizenship. The dancers’ sweat-soaked sari is the symbol of that unrecognized labour – and hence the title of the book. Srinivasan introduces and deals with several complex ideas in the book – including the idea of Bharatanatyam dancers as upholders of cultural nationalism

In the course of her inquiry, she examines and demonstrates the debt owed by Ruth St Denis to Indian dance which has never been recognised or acknowledged. Following the work of Edward Said’s Orientalism, the author places this squarely in the lap of US colonialism and imperialism of the early twentieth century. Srinivasan points out that Ruth St Denis’s ‘modernist’ project of American dance reproduced ‘nachwalis dance’ of India without acknowledging it; the contribution made to her career by Indian male performers was erased from public discourse; St Denis benefitted from Indian dancers and teachers without honouring them. The nachwalis labour was effectively effaced through the process of absorption of their dance practices without acknowledging their contribution.

Ruth St Denis never admitted the contribution of Indian bodies to her dancing, yet she is touted as this great innovator of ‘modern dance’ – the guru of the legendary Martha Graham. Invoking the French philosopher Foucault’s ideas, Priya Srinivasan describes Indian dancers as the subalterns: male and female Indian labour in the context of race-charged US citizenship debates.

The author argues that they highlight the racist overtones and underpinnings previously sidelined in North American Orientalist discourse. Modern dance attempted to establish itself as new and original, while denying its Oriental origins. This is part of the construction of the larger myth that US citizenship is a purely a white endeavour.

The author, while demonstrating this, nevertheless resists the temptation of going to the other extreme: of clinging to the idea that Bharatanatyam – and Indian classical dance – in its twentieth century form as somehow ‘authentically traditional’. She locates those ideas too in India’s independence movement and its drive to establish a national identity.

In Chapter 6, Srinivasan argues that while resisting the dominant American culture represented by White American nationalism in the early twentieth century, Indian dance too, presented its own problems of cultural nationalism. Nevertheless it offered and offers an alternative to the dominant mainstream US citizenship, and allows young Indian dancers to access possible alternatives to assimilation – however temporary.

Srinivasan merges ethnography, history, critical race theory, performance and post-colonial studies among other disciplines to investigate the embodied experience of Indian dance. She is the ‘unruly spectator’; the dance ethnographer who frames the whole field of Indian dance within the larger question of race, gender, class and politics. This book is not for everyone. It is written very much in academic language and apart from academics, few readers will be able to read the book from cover to cover and be able to glean the thrust of the author’s argument. That does not take away from it the fact that it is an important book that needed to be written; an argument that had to be made. Srinivasan makes it forcefully, clearly, honestly, fearlessly, and with a great degree of sophistication.

Priya Srinivasan is Associate Professor in Critical Dance Studies at the Department of Dance, University of California, Riverside. In 2008, she received the Gertrude Lippincott Award given by the Society of Dance History Scholars for the best English-language article published in dance studies.

The author argues that by examining the Indian-American dancing woman as a labourer, one can see her negotiating the terms of US citizenship