2 minute read

Indian bookscape: New sensibilities in literary translation

from 2012-02 Sydney (2)

by Indian Link

In Kerala, Gabriel Garcia Marquez is among the most popular novelists - thanks to his translated works in Malayalam. Translations of popular fictions, non-fictions and classics are very much in demand in India and adorn bookshelves in many urban homes like status tags.

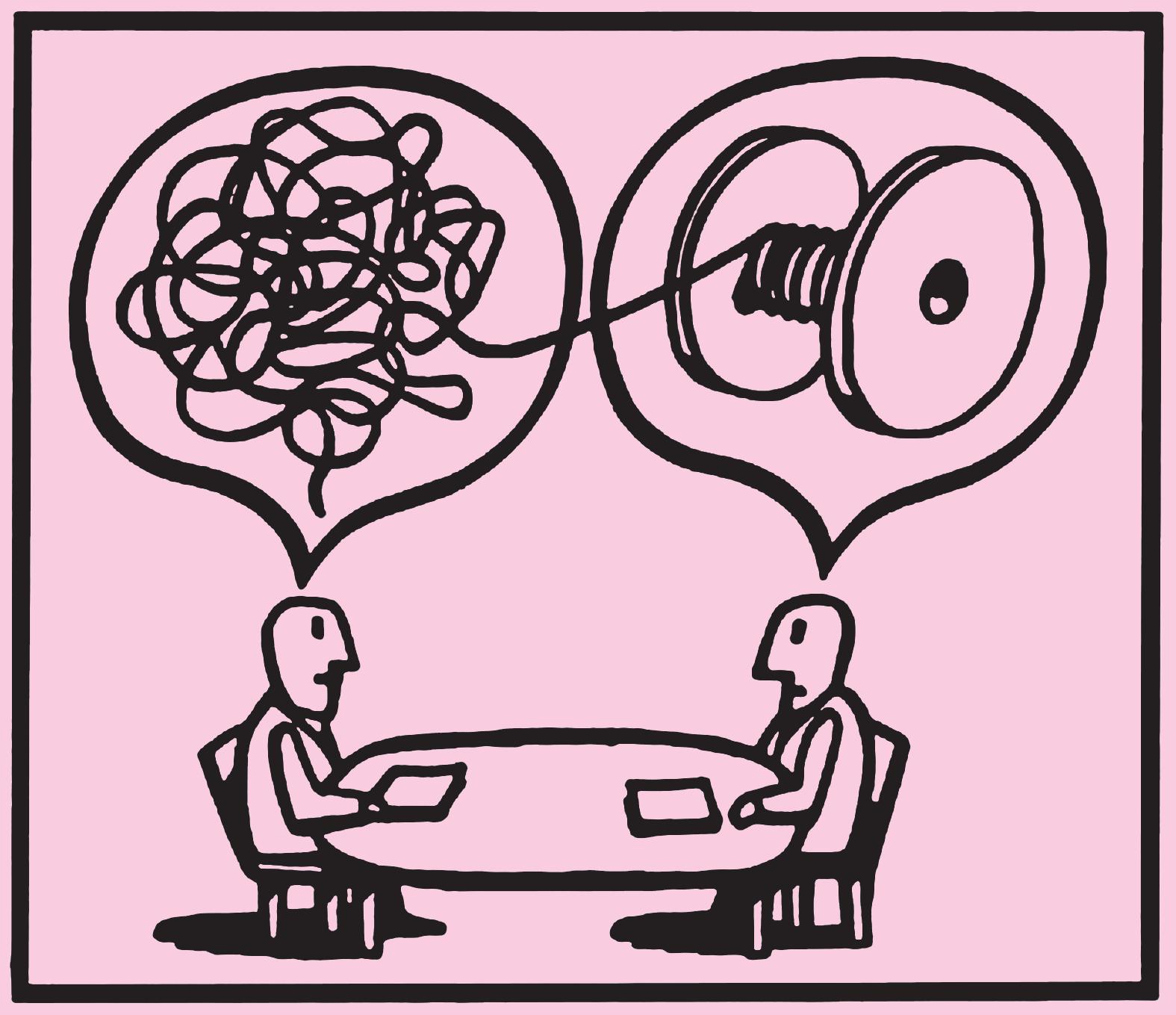

For the translator, it is no easy job, for he/she has to stick to the intent and spirit of the original while choosing the words.

In post-colonial India, regional languages are fighting with English as link tongues and translations often surpass originals in quality of retelling.

“My book has been translated beautifully... At times, I feel it is better than the original,” Claudine Le Toureur d’lson, the French author of Hira Mandi, says. “The English translation by Priyanka Jhijaria, released this year, has been able to bring out the essence of the story in a way that relates to the Indian and Pakistan’s social milieus”.

History says India forged its first cultural-literary links with the West in the 6th century BC when Vedic ideas were expounded by Greek thinkers Plato and Galen.

The whole paradox of translation is that a “translator gives new life to something that has been written, but at the same time has to stick to the intent and spirit of the original,” says writer and “bhasa” campaigner Namita Gokhale.

“It is more difficult to do a brilliant translation than write a good book. A translation has to retain the texture, idioms and metaphors of the source language rather than flattening into homogenised English,” Gokhale notes.

Diplomat-writer Navdeep Suri, who translated two of his grandfather Nanak Singh’s novels, Saintly Sinner (Pavitra Paapi) and A Life Incomplete (Adh Kidhiya Phool) says he chose “simpler books with easy grammar and syntax” from his grandfather’s collection.

“My Pubjabi does not relate to the characters in many of my grandfather Nanak Singh’s early books because I grew up in the city,” Suri said at a discussion, Let’s Talk Translation, hosted by publisher Harper Collins-India in the capital recently.

Suri had to give up translating Nanak Singh’s literary milestone Chitta Lahu because “he recognised that it was beyond him to translate the novel”.

“The characters were so earthy and rooted in rural Punjab of the 1930s,” Suri said.

Kerala-based poet and sporadic translator K. Satchidanandan agrees that the “Indian consciousness is a translating consciousness”, but he cites Kerala as an example where translation has worked.

“I come from a language (Malayalam) where we translate works by Marquez, Llosa and Saramago. It was once remarked that Gabriel Garcia Marquez was the most popular novelist in Kerala,”.

Satchinandan says he would “rather have more translations in Indian languages - intra-language translations - so that both languages are empowered.”

“It was necessary to achieve equity in translation to give equal representation to every linguistic group and literature,” Namita Gokhale echoes.

Writer and translator Ira Pande, who calls herself “an accidental translator”, says a translator has to share a profound relationship with the author.

“I felt that I had the right to translate my mother’s (Hindi novelist Shivani’s) literature - whom I knew so well - the way I wanted to. But with writer Shyam Manohar Joshi, I could not think of doing it the way I wanted to,” Pande notes.

Arunava Sinha, who has translated Bengali novelists Sankar’s and Buddhadev Basu’s novels, says he shares “a love-hate relationship with Sankar.”

“Sankar is grateful that I have carried him beyond Asansol (in West Bengal) - the last frontier of the Bengali-speaking people,” Sinha laughs.

The praxis of translation - and its future - in the postcolonial world revolves around three rationalisations: “normalisation of English, normalisation of markets and normalisation of the Anglo-notion of excellence”, Alok Rai, a professor of English at Delhi University, suggests.

Anything that does not work in English is not world class, Rai explains. “Either it has to be managed to work in English or it does not work. What is likely to emerge is a standardised homogeniety - an Anglo-notion of excellence”.

Books are translated only if there is a market, Rai notes.

Writer and translator Neelabh, who translated Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things in Hindi, observes that his “book worked because Roy had won the Booker Prize and publishers were keen to print it”.

Madhusree Chatterjee