2 minute read

Tales of a forgotten past

from 2009-09 Sydney (2)

by Indian Link

literally from the city and the country’s conscience.

It was after reading an article in Time magazine about how ‘a number of religious and historic buildings, especially in New Delhi, were falling into ruin due to lack of care and restoration’, that Elliston decided to travel to India to picture them.

Walking through the Storm Gallery in Surry Hills earlier this month, the hues and colours of India came flooding back.

Taking one down the nostalgic lane, were Sydney-based photographer Peter Elliston’s photographs of New Delhi, or perhaps one should one say, an ‘old’ Delhi.

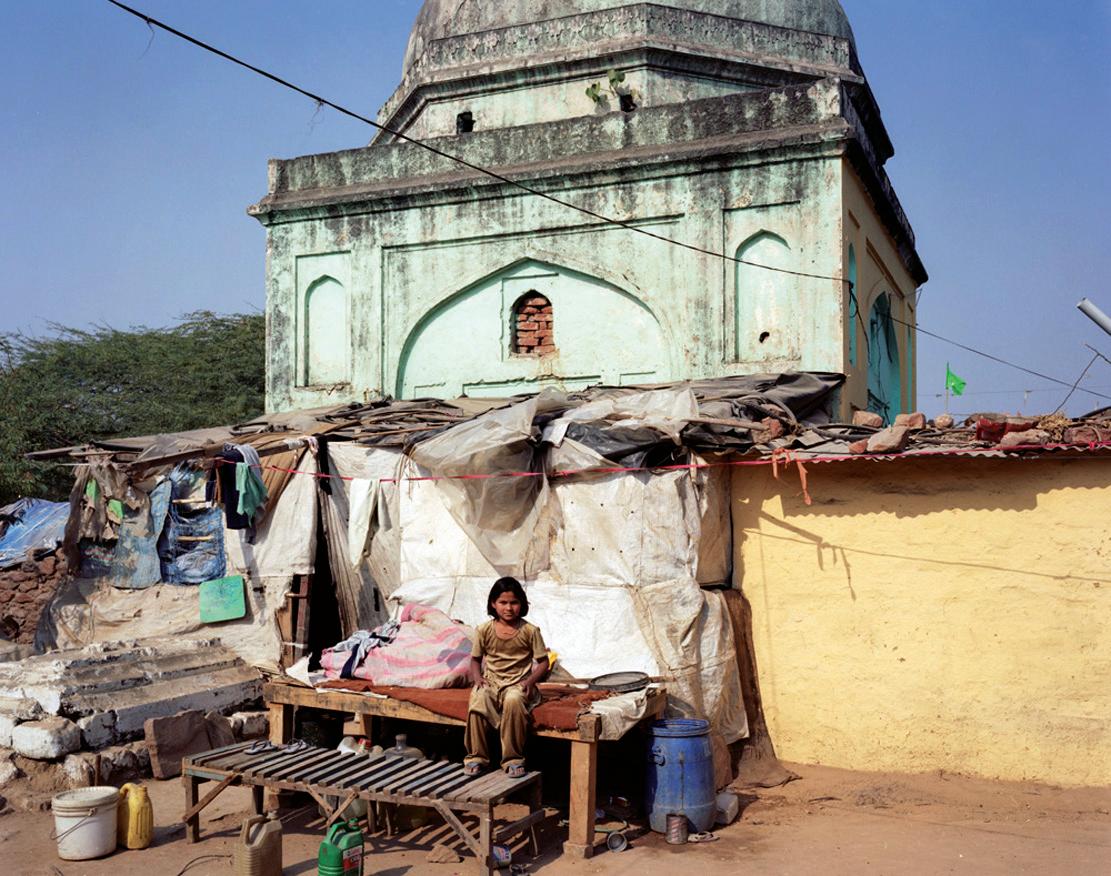

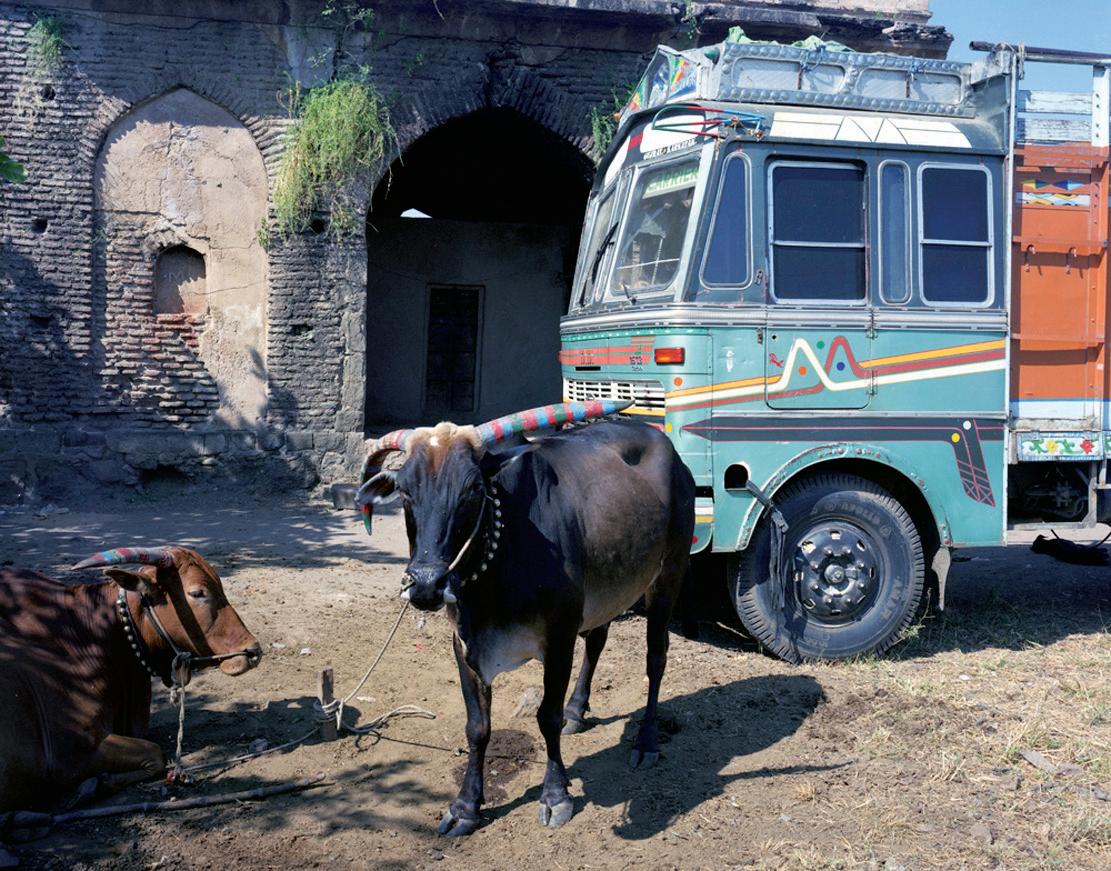

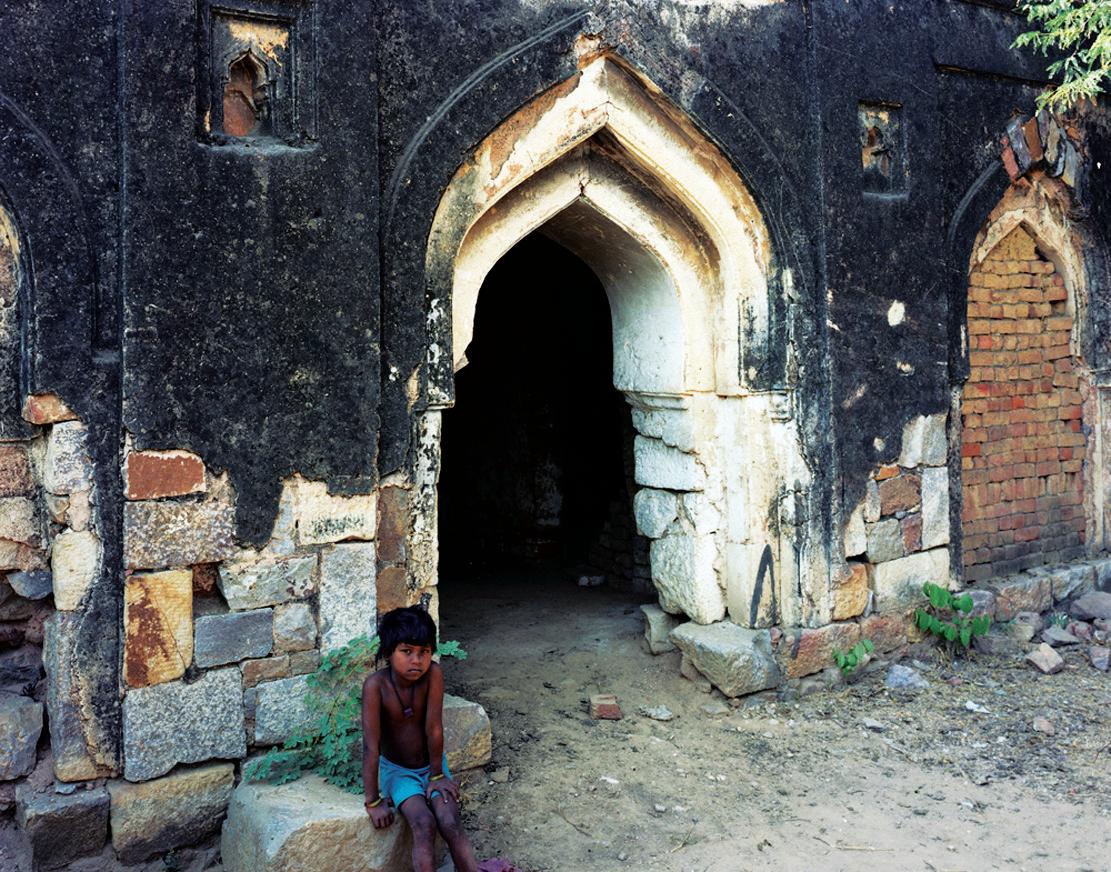

Even as the ‘emerging’ superpower grows rapidly in the eyes of the world, Elliston’s lenses capture an India, forgotten and tucked away in its alleys, amidst its countless people. Aptly titled Broken Monuments, the exhibition displayed some of the oldest monuments in the capital, crumbling at their core because of sheer neglect.

Unlike the famed Taj Mahal, many of these monuments including the Jantar Mantar observatory and the Qutub Minar, have been left to fend for themselves even as they face the prospect of disappearing

“I am always looking for new projects in photography and the neglected monuments of New Delhi seemed interesting. I didn’t want to just photograph regular tourist monuments, which would offer nothing new for me or my audience. But I sought monuments that have been garnered for domestic purposes and perhaps lived in,” Peter Elliston told Indian Link.

“This seemed like an interesting and original project. Also, in my photography I have been interested in monuments from around the world such as at Petra in Jordan and I wanted to show them in the context of the surrounding landscape,” he added.

The pictures include a sufi tomb near Aurangabad, a girl at a masjid in Mehrauli, a not-in-use swimming pool, the Kudyliutti tomb, and the Rangin Gate among other things.

Goats, cows and children are the only visitors at these broken monuments. Elliston, whose work is held in collections around the world including Paris and London and locally in the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, NSW State Library and many public and private collections, has travelled all over the world photographing people, places and monuments and has published four books of his own. His work has been published widely and exhibited in many solo and group shows in Australia and overseas and is well known for his portrait series documenting people swimming at Wylie’s Baths, Coogee.

When asked if the choice of these subjects were a conscious reflection of the real India, the renowned artist observed, “I didn’t seek to make a statement about India today, except perhaps to refer to the fact that monuments are disappearing and that India has such a rich history. Whether or not children and goats appear in a photograph was somewhat random. If a photo was more interesting with a person in it, then he or she would be included. For some photos of course I had little choice about whether people were included.”

His 5x4’’ camera brings out the distinct, bright and potent colours of his subjects, the monuments and the backdrops in his pictures. According to him, a photographer does not go unnoticed with such equipment and especially in places like New Delhi, where people and noise are a constantand he has attempted to capture the quiet moments in his photographs. Elliston points out that lovers of all things India will not be disappointed with this collection of quietly perceptive images, “as they are full of a subtle honouring of things gone past, and serve to remind us of everything underappreciated – our history, our culture, our heritage, our relationship to the past.”

Interestingly, it was Elliston’s amused taxi driver who unwittingly contributed to the name of the exhibition when he said he was interested in neglected sights rather than the splendour of the likes of the Taj Mahal. “Ah! What you want to see is ‘broken’ monuments,” the driver told Elliston.

One hopes that these monuments, signifying the country’s rich heritage, culture and the bygone era, are restored to their past glory for the sake of the future generations. Else, we may have to rely only on prints or on our memories to remember them.