WHAT IS REALITY?

Artificial intelligence has arrived

Artificial intelligence has arrived

Several members of our community gathered in schools, studios, and social settings around the country to mark the annual National Industrial Design Day celebration on March 5, 2023. As always, it’s a great opportunity for networking and community-building while taking some time to appreciate all that industrial designers do.

Publisher IDSA 950 Herndon Pkwy. Suite 250 Herndon, VA 20170

P: 703.707.6000 idsa.org/innovation

Executive Editor Chris Livaudais, IDSA chrisl@idsa.org

Contributing Editor Jennifer Evans Yankopolus jennifer@wordcollaborative.com 678.612.7463

Graphic Designers Nicholas Komor 678.756.1975 0001@nicholaskomor.com

Sarah Collins 404.825.3096 spcollins@gmail.com

Advertising IDSA 703.707.6000 sales@idsa.org

Subscriptions/Copies IDSA 703.707.6000 idsa@idsa.org

Annual Subscriptions

Students $50

Professionals / Organizations

Within the US $125 Canada & Mexico $150

International $175

Single Copies Fall $75+ S&H

All others $45+ S&H

24

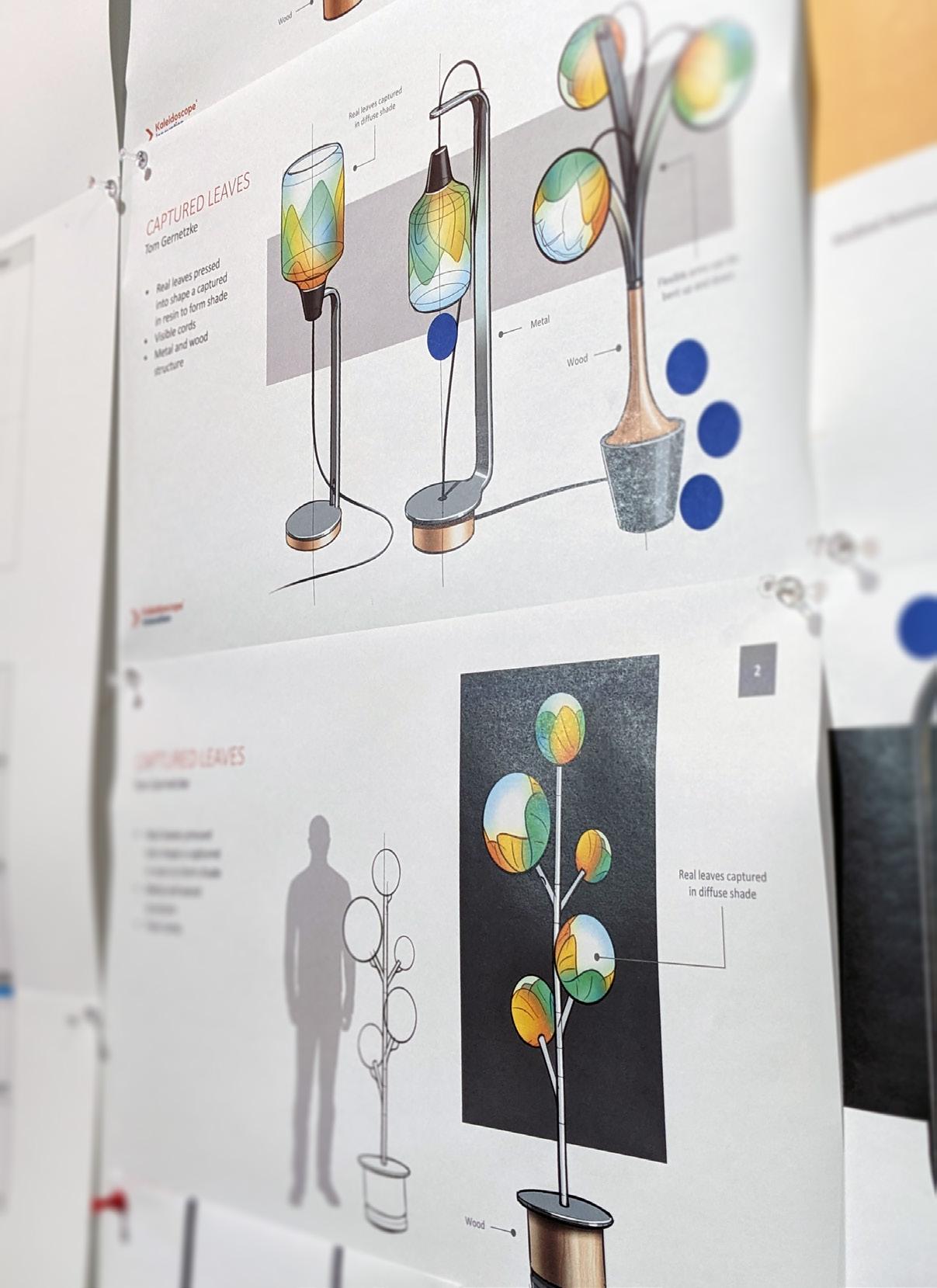

by Emilie Williams, IDSAby Tony Siebel, IDSA, Tom Gernetzke, and Caterina Rizzoni, IDSA 38

20 IDSA.ORG Redesign IN EVERY ISSUE

4 In This Issue

6 Chair’s Report by Lindsey Maxwell, IDSA

8 From HQ by Jerry Layne, CAE

9 Beautility by Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA

14 Women on Design by Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman, IDSA

16 ID Essay by Steven R. Umbach, FIDSA

by Roger Ball, IDSA58

by Max YoshimotoCover: Using reference images and blending in Midjouney to experiment with translucent CMF effects. Courtesy of Hatch Duo.

Opposite: On the Moon by Eric Ye, S/IDSA. Image generated in DALL-E using the prompt “An astronaut is seating on a chair which is made from pink foam spray chair in style of blobism, the background is the moon surface and universe.”

Innovation is the quarterly journal of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), the professional organization serving the needs of US industrial designers. Reproduction in whole or in part—in any form—without the written permission of the publisher is prohibited. The opinions expressed in the bylined articles are those of the writers and not necessarily those of IDSA. IDSA reserves the right to decline any advertisement that is contrary to the mission, goals and guiding principles of the Society. The appearance of an ad does not constitute an endorsement by IDSA. All design and photo credits are listed as provided by the submitter. Innovation is printed on recycled paper with soy-based inks. The use of IDSA and FIDSA after a name is a registered collective membership mark. Innovation (ISSN No. 0731-2334 and USPS No. 0016-067) is published quarterly by the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA)/Innovation, 950 Herndon Pkwy, Suite 250 | Herndon, VA 20170. Periodical postage at Sterling, VA 20164 and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to IDSA/Innovation, 950 Herndon Pkwy, Suite 250 | Herndon, VA 20170, USA. ©2023 Industrial Designers Society of America. Vol. 42, No. 1, 2023; Library of Congress Catalog No. 82-640971; ISSN No. 0731-2334; USPS 0016-067.

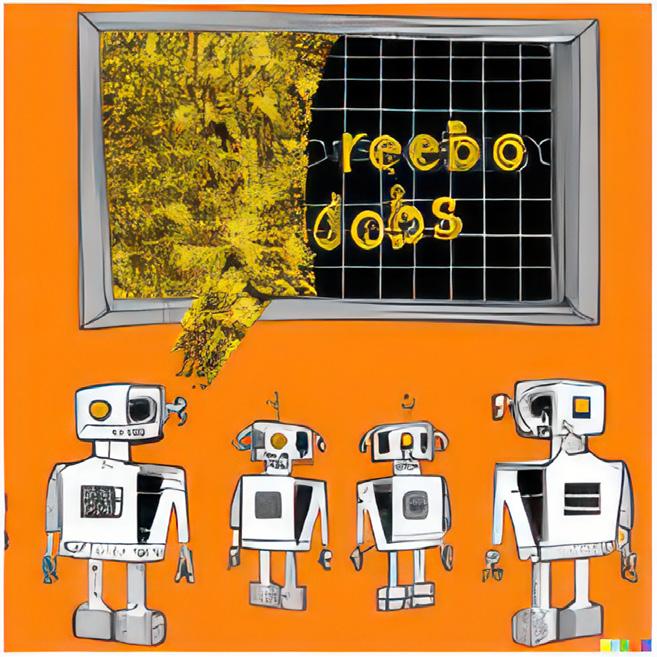

The integration and sophistication of artificial intelligence (AI) in the products and services we use every day is expanding at an increasingly exponential rate. At this point, it might be easier to list the industries not using it than those who are. Broadly speaking, this technology has largely been developed and implemented outside the view of day-to-day consumers. We all benefit from it, but most don’t have any idea of just how pervasive it is or of how it actually works. A few notable customer-facing exceptions are things like Apple’s Siri digital assistant, social media algorithms, self-driving features found in some newer automobiles, and Content-Aware Fill in Adobe Photoshop. Yet for industrial designers, were just now seeing a glimpse of wild new horizon ahead of us—one where concept generation workflows are dramatically sped up and the lines between machine and designer become ever blurrier.

Recently, public versions of image generation AI software have begun to gain in popularity and accessibility. In simple terms, many of these tools use a string of words as the input prompt, which is used to create a completely original digital image as the output. The resulting images can then be refined further by modifying the words used to describe the image or by selecting portions of the image to retain and then re-creating the areas around it until the desired outcome is achieved. This allows pretty much anyone with a computer and an imagination to express themselves in previously unthinkable ways. Artists can put down their brushes but still create strokes, illustrators can envision expressive new characters without the need for a pen, and photographers can give up their camera and yet still capture a moment (that never happened) in life-like detail.

What does this mean for industrial designers? We are, after all, heavily reliant on visual output as a primary delivery mechanism for our work. We create sketches, renderings, and other visualizations using a wide variety of physical and digital tools. This is nothing new; computers have been central to our process since their introduction. But programs like DALL-E and Midjourney are making us rethink our creative relationship with software and, at the same time, pose myriad new questions about ethics and the authorship of intellectual property. Even the idea of one’s personal

talent or creativity could be up for debate when software is responsible for producing a finished image.

In an October 2022 interview on the Daily Show with Trevor Noah, OpenAI chief technology officer Mira Murati discussed the creative capabilities of DALL-E 2, the ethical and moral questions that using AI raises, and how artificial intelligence can enhance and shape the imagination of society. When asked about how AI will affect jobs, Murati responded, “We see them as tools. An extension of our creativity or our writing abilities. These concepts of extending human abilities and being aware of our vulnerabilities are timeless … it’s really just an extension of your imagination.”

As exciting as it currently is, we must also acknowledge that this technology is still in a nascent stage. AI has a long way to go before being able to completely replicate what humans do naturally, particularly in areas that demand any sort of emotional, cultural, or contextual consideration. For the process of industrial design, these image-generating tools also don’t currently have any references to ergonomics, materials, or manufacturing data used in their calculations. The only output is 2D images that occasionally have unresolved areas as if the software couldn’t quite figure out what to put there. That said, it’s not difficult to envision a future where ergonomics, materials, and manufacturing data sets (along with countless others) are incorporated into the AI engine, which would in turn create output that is both practically feasible and perhaps even emotionally cognizant of who the end user(s) could be.

We have a fascinating new tool at our disposal, and there is a lot to unpack about how we can leverage it to our creative advantage. In this issue we hope to explore how image-generating AI software, and other emergent AI technologies, will impact the work we do as industrial designers. And yes, while updates to some of the AI platforms have been released since these articles were written in February 2023, the opportunities, concerns, and possibilities the contributors address in their articles will remain relevant for months and years to come. Get ready, it’s going to be a wild ride!

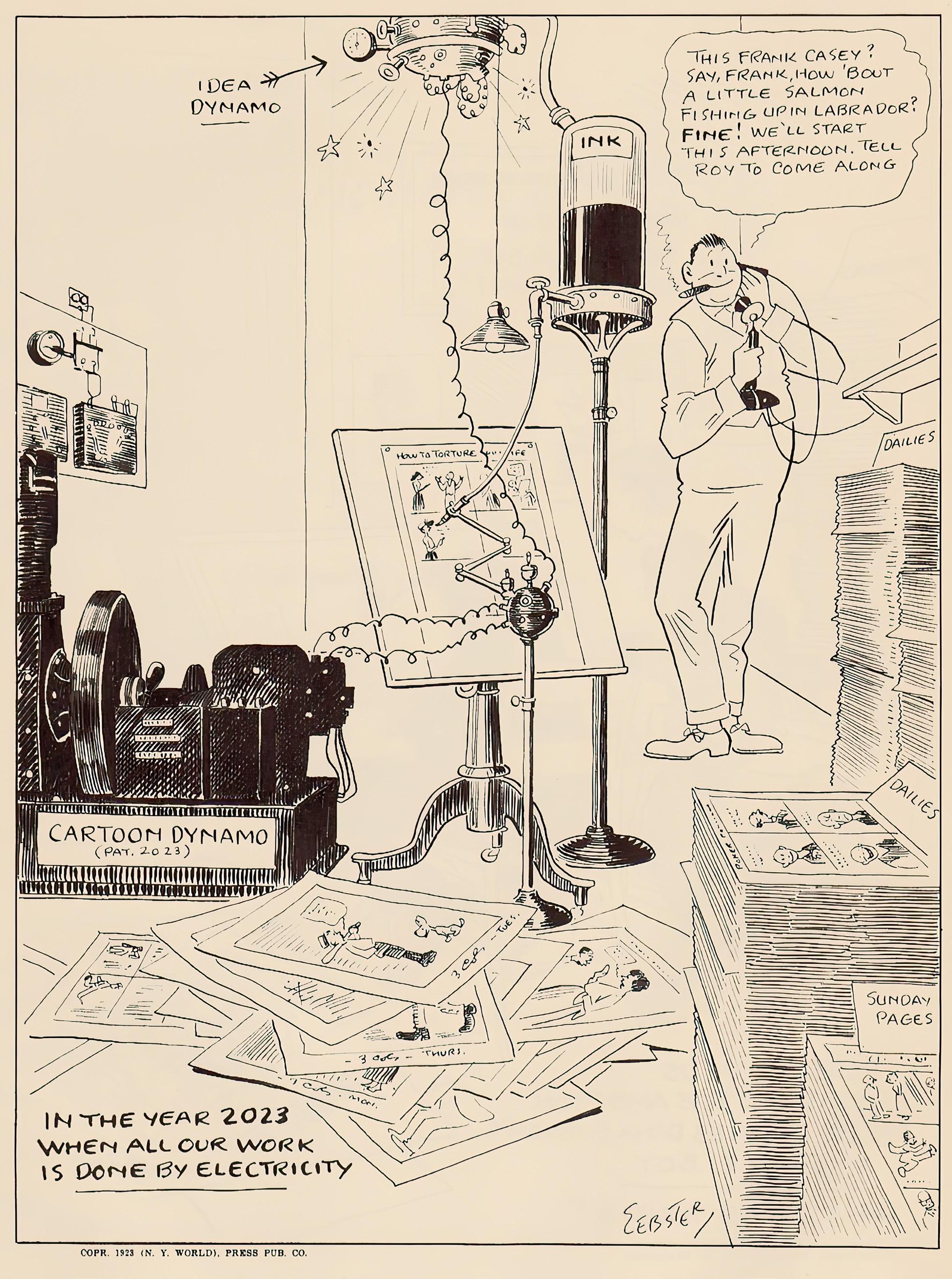

In the above cartoon, which ran in the New York Tribune in 1923, Harold Tucker Webster envisioned a future in which a newspaper cartoonist would use electronic contraptions to generate new ideas and draw them onto paper. These innovations would give the cartoonist more free time for other pursuits, like planning a fishing trip with his buddies. Exactly 100 years later, you could say that ChatGPT is the real-life Idea Dynamo and DALL-E and Midjourney are the Cartoon Dynamo.

Iprobably wouldn’t be the vice president of Teague if it weren’t for IDSA, or at least for the members I met when I was a freshly graduated industrial designer. It might sound dramatic, but I am truly indebted to the numerous women from IDSA who networked with me, gave me portfolio feedback, invited me to see their work, and eventually encouraged me to apply for an open position at Teague.

Industrial design remains a male-dominated industry: Women make up just 19% of our profession, according to the Design Salary Guide by Coroflot. That’s why my early history with IDSA is so meaningful: It was women who carried me through, despite being few and far between in the industry. I didn’t feel as isolated because I had a community—brought together through IDSA—behind me.

The Many Values of Community

IDSA is the set and setting for designers to uplift one another. This is one great purpose of a professional organization. Together, we have the capabilities to nurture and promote the careers of all underrepresented designers, ultimately bringing much-needed balance to the industry. There’s a good reason we have a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Council—to take real action toward increasing minority representation in IDSA’s core programming, leadership, and membership; increasing access to industrial design

education; and dismantling inequities within design at large. A greater spectrum of identities is in the best interest of our industry and the world we affect through our products, environments, and ideas.

The practice of industrial design is facing an identity crisis of its own. Our roles have changed dramatically in the last decade as we have watched the field of industrial design evolve and grow to intersect with UX, UI, AI, and 3D—so many acronyms; it’s easy to get lost. New design practices and technologies will continue to emerge and disrupt the status quo over and over again, and the need to recalibrate our identities as designers will not cease.

It is important that we address these challenges—the changing, growing practice—as an organization. IDSA can play a crucial role in helping members navigate these changes and stay informed about the latest developments in the field. By providing a platform for discussion, learning, and collaboration, we can help shape the future of industrial design.

On the Horizon

I’m a people-first person. That’s true wherever I am in a leadership role, whether it’s at Teague or IDSA. The value of this organization lies first and foremost with our members, as I experienced myself early in my career. My primary goal as Board Chair is to support our existing `and future members.

I hope to foster the same kind of support for others that I experienced myself.

This begins first with finding our next Executive Director. We want to do this the right way—that means slowly and deliberately. We’re establishing a search committee with external voices from the design community to help us find the right person who can help our members navigate what the future of the industry will be. We are committed to finding someone who is not only knowledgeable and experienced but also forward thinking and excited about the future of industrial design.

In the coming months of 2023, I’m also looking forward to sharing more about the exciting changes we’ve made to our awards and conferences programming. We’ve created new committees for both programs, and I’m proud to say they’re full of highly talented designers who are dedicated to elevating these two important offerings. In the future, we will share an inside view of the IDEA review process—get ready for some lively debate over the winning entries! For conferences, the committee will now include a much larger, diverse group that will identify conference themes that are most relevant to you, our members and community. After the topics and themes are agreed upon, the committee members will curate the speakers, emcees, workshop facilitators, moderators, and pane`lists.

We have also begun testing an IDSA membership service for schools that allows for greater community access to industrial design students. This is a wonderful benefit to our up-and-coming professional members and helps to increase a diversity of perspectives at IDSA.

I am proud of the improvements IDSA has made this last year and know there are many more to come in the years that follow. The ever-changing landscape of industrial design may seem daunting, and finding our place within it may feel like a challenge. But this, in my opinion, is the most exciting time in history to be an industrial designer. With technology advancing rapidly and global needs to solve for, we have seemingly endless opportunities to make real impact with our work.

To truly make a difference, we need a strong point of view and advocacy for our profession. The members of IDSA hold the key to creating that voice and identity for industrial design.

I look forward to meeting many new faces and seeing old friends at the International Design Conference this August. Though it’s been 20 years since we’ve held the conference in New York, we’re honored to be returning to the design hub after such a long time away. See you there.

—Lindsey Maxwell, IDSA, IDSA Board Chair lmaxwell@teague.comSince stepping into the role of Interim Executive Director after Chris Livaudais’ departure at the end of last year, I’ve been humbled by the kind words from so many of you. With your support, and that of the Board and Staff, I’m excited for a very successful year ahead.

While there is plenty of reason for optimism about our future, a simultaneous reality is beginning to take shape. It’s no secret that the economy has been facing turbulence, but it’s not solely about inflation’s impact on the price of everyday items like food and gas or what seems to be a long-term debate over a looming recession. Conversations with our members over the past several months reveal a growing trend of lower-than-expected company revenues and, in some cases, layoffs.

My first major communication to you as Interim Executive Director is not meant to be doom and gloom. With the passion and commitment of our Board, Staff, and greater IDSA community, I am confident that we will overcome these challenges. However, I believe that as a leader within the profession, IDSA has a responsibility to be honest and proactive about the realities we currently face.

At the Board of Directors meeting this January, with both Board and Staff in attendance, I shared my plan for the year ahead. Borne out of conversations with the Board and member feedback and an understanding of what’s happening within the industry, we must demonstrate agility and provide pertinent resources so that our members can continue to derive value from IDSA and feel equipped to face challenges that might lay ahead.

I would like to briefly touch on two areas of our 2023 plan:

Events are central to IDSA’s identity. Nearly five years ago, a series of visioning sessions yielded a recommitment to what we’ve always been great at: in-person connections. But a lot has changed in the world since then. Economic uncertainties, the impact of COVID-19, and a much-needed spotlight on diversity, equity, and inclusion have shaped a

new reality. No longer can IDSA afford to singularly focus on the in-person experience or frameworks of the past. That’s why this year we’re investing our resources to enhance the entire event experience, from thoughtful content curation and diverse event leadership to strengthened programming partnerships and streamlined virtual access. More to come in the second half of the year.

At last year’s IDC in Seattle, WA, IDSA announced it was bolstering organizational resources to better support the academic community. Additionally, the vision for a new Academic Membership program was introduced. As an evolution of our highly successful Group Membership program, Academic Membership will uniquely package new and existing offerings designed for students, educators, and industrial design programs. Early excitement about the pilot, which kicked off in January, suggests we’re on to something big. Stay tuned for the rollout of the full program later this year.

Professional chapters and sections have always been, and remain, a core part of IDSA’s programming. We’re continuing to improve our support for volunteer leaders by exploring ways to better equip them with training through the Community Leadership Institute and access to IDSA funds for programming. We are strategizing on different models and hope to share creative solutions with them this year.

We have a challenging but promising year ahead. With the resilience and strength of the IDSA community, I am certain we will emerge stronger than ever. In the meantime, we are committed to supporting our members and providing the resources, content, and opportunities to help our community succeed.

—Jerry Layne, CAE, Interim Executive Director jerryl@idsa.org

For this issue, I decided to emulate the modus operandi of my colleague Scott Henderson, IDSA: interview a celebrity. So I got in touch with ChatGPT, sibling to the visual image maker DALL-E, both created by the artificial intelligence research laboratory OpenAI. ChatGPT is like Cixin Liu’s “Big Quantum” in his sci-fi book The Supernova Era (written before Three Body Problem). The AI in his story is a kind of super-democratic computing tool. Like in a massive multiplayer game, it gathers everyone’s ideas and individual desires into summaries to foster human-scale dialog. “That’s right. They are all speaking, but only Big Quantum heard the nearly two hundred million messages. It summarized them into the one statement you heard,” says

Pan Yu in the book. The value of this AI is that it makes “sense” of all its data; it says what we already know because its database is everything we know.

ChatGPT, like Big Quantum, is not making things up; it’s assembling information and making it sound good. The composing is artificial, but the ideas are ours— our conventional wisdom. I was surprised at how much ChatGPT knows about industrial design! Which means that the general public finally now knows what we do. My conversation with ChatGPT is presented here more or less verbatim. Although as the December 26, 2022, New York Times headlined—“Did a Fourth Grader Write This? Or the New Chatbot?”—decide for yourself!

Tucker Viemeister: Am I crazy to interview a chatbot?

ChatGPT: It is not necessarily crazy to interview a chatbot for an article about industrial design or any other topic. Chatbots like me can provide a broad overview of a subject and can be a convenient and efficient way to gather information. However, it is important to note that my responses are based solely on the information that I have been programmed with and do not reflect the personal experiences or opinions of an individual.

It is up to the individual journalist or writer to decide whether interviewing a chatbot is appropriate.

Viemeister: OK, I do think it’s appropriate! I want to find out what’s in your database. First, what does a chatbot know about industrial design?

ChatGPT: Interviewing a chatbot like me could provide a broad overview of the field and help to familiarize readers with the basic principles and concepts of industrial design. I can provide information on the history and evolution of the field, the role of industrial design in shaping the products and systems that people use every day, and the key skills and techniques that industrial designers use to create functional and aesthetically pleasing products.

Viemeister: Tell me, why do you think industrial design is important for the future?

ChatGPT: Industrial design is important for the future because it plays a critical role in shaping the products and systems that people use every day. It is a multidisciplinary field that combines creativity, engineering, and business to create functional and aesthetically pleasing products that meet the needs of users and the market.

There are several reasons why industrial design is important for the future:

1. Industrial design helps to create innovative products that meet the changing needs and preferences of consumers. As technology and society evolve, industrial designers are constantly looking for ways to improve and update existing products, as well as to create new products that meet emerging needs.

2. Industrial design is a key factor in the success of a product. A well-designed product is more likely to be successful in the market, as it is more appealing to consumers and easier to use. Industrial design also plays a role in the sustainability of a product, as designers consider the environmental impact of a product throughout its lifecycle.

3. Industrial design helps to drive economic growth. The products and systems created by industrial

designers create jobs and contribute to the economy. In addition, industrial design plays a role in helping companies to stay competitive in a global market.

Viemeister: What do you base these projections on?

ChatGPT: As an artificial intelligence, I have been programmed with a large dataset of information on a wide range of topics, including industrial design. I have been trained to understand and analyze text input and generate appropriate responses based on that input. This allows me to provide information and answer questions on a wide range of topics. I do not have personal experiences or opinions, and my responses are based solely on the information that I have been programmed with. Is there anything else you would like to know about industrial design?

Viemeister: Why don’t industrial designers make more money if their work is so valuable?

ChatGPT: It is important to note that the value of industrial design work can be difficult to quantify, and designers may not always receive financial compensation that is commensurate with the value of their work. However, many designers are motivated by the opportunity to create products that are valued and appreciated by consumers, and they may find other forms of fulfillment and satisfaction in their work.

Viemeister: Have you heard of the word “beautility”?

ChatGPT: Beautility is a term that is used to describe products that are both beautiful and useful. It is often used in the context of design, to describe objects that are aesthetically pleasing and also serve a practical purpose. Beautility is a concept that has been around for many years, and it has been a key consideration in the design of a wide range of products, from furniture and household objects to consumer electronics and other products. Many designers strive to create products that are both beautiful and useful, as they believe that such products are more likely to be appreciated and valued by consumers.

Viemeister: I guess I didn’t coin the word then. How important is beauty to successful industrial design?

ChatGPT: Beauty is an important, but it is not the only factor. A product that is aesthetically pleasing is often more appealing to consumers and can contribute to its success in the market. However, beauty is subjective and can vary depending on cultural and personal preferences. Therefore, it is important for industrial designers to consider a wide range of factors when designing a product, including its function,

usability, sustainability, and cost. Industrial designers must also consider the cultural and social context in which the product will be used, as well as the environmental impact of the product throughout its lifecycle.

Viemeister: Here’s a trick question: What is the difference between design thinking and industrial design?

ChatGPT: Design thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves understanding the needs of users, generating creative ideas, prototyping and testing solutions, and iterating on those solutions until a satisfactory result is achieved. It is a process that can be applied to a wide range of fields and industries, including product design, service design, and organizational design.

Industrial designers use design thinking as part of their process, but they also have specialized knowledge in areas such as materials, manufacturing processes, and ergonomics, which allows them to create functional and aesthetically pleasing products that meet the needs of users and the market.

Viemeister: Who are the most important industrial designers?

ChatGPT: There have been many important industrial designers throughout history who have made significant contributions to the field. Some of the most well-known include:

1. Raymond Loewy: Loewy was an influential industrial designer who is credited with designing some of the most iconic products of the 20th century, including the Coca-Cola vending machine and the Greyhound Scenicruiser bus.

2. Dieter Rams: Rams is a German industrial designer who is known for his minimalist design philosophy and his contributions to the development of the Braun brand.

3. Jony Ive: Ive is a British industrial designer who was the Chief Design Officer at Apple and is credited with designing many of the company’s most iconic products, including the iPod, iPhone, and iPad.

4. Chuck Pelly: Pelly is an American industrial designer who has designed a wide range of products, including automobiles, motorcycles, and consumer electronics.

5. Karim Rashid: Rashid is an Egyptian-born industrial designer who is known for his colorful and futuristic designs and has designed a wide range of products, including furniture, home decor, and consumer electronics.

Viemeister: It’s interesting to see who you chose! Makes me wonder what your selection criteria are based on. Is it some kind of Internet hit parade?

ChatGPT: No, my selection criteria is not based on internet popularity. As an artificial intelligence, I do not have access to the internet or other external sources of information. My responses are based solely on the information that I have been programmed with. In the case of the industrial design firms I listed, I selected them based on their reputation and contributions to the field of industrial design, as well as their history and the range of clients they have worked with. I did not consider internet popularity as a factor in my selection.

Viemeister: What can industrial designers do to become more successful?

ChatGPT: There are several things that industrial designers can do to become successful in their field:

1. Develop a strong foundation in design principles: Industrial designers should have a solid understanding of design principles such as form, function, aesthetics, usability, and sustainability.

2. Build a diverse skill set: Industrial design is a multidisciplinary field, so it is important for designers to have a diverse skill set that includes creativity, technical expertise, business acumen, and problemsolving skills.

3. Stay up to date with industry trends and technology: Industrial designers should be aware of the latest trends and technologies in the field to ensure that they are creating products that meet the needs and preferences of consumers and the market.

4. Build a strong portfolio: Industrial designers should develop a strong portfolio of their work to showcase their skills and abilities to potential employers or clients.

5. Network and seek out opportunities for professional development: Industrial designers should seek out opportunities to network with other professionals in the field and participate in professional development activities to enhance their skills and knowledge.

6. Build a strong personal brand: Industrial designers should work to build a strong personal brand by consistently delivering high-quality work, being a team player, and demonstrating their expertise and passion for the field.

Overall, becoming a successful industrial designer requires a combination of strong design skills, technical expertise, business acumen, and a passion for the field. By consistently delivering high-quality work and seeking out opportunities to

grow and learn, industrial designers can position themselves for success in their careers.

Viemeister: What are the key skills industrial design students need to learn?

ChatGPT: There are several key skills that industrial design students should learn to be successful in their careers:

1. Design principles: students should learn the fundamental principles of design, including form, function, aesthetics, usability, and sustainability.

2. Creativity: Industrial designers need to be able to generate creative ideas and solutions to design challenges.

3. Problem-solving skills: Industrial designers must be able to identify and solve complex problems in a creative and effective manner.

4. Technical skills: Industrial design students should learn how to use design software and other tools to create accurate and detailed designs.

5. Communication skills: Industrial designers must be able to effectively communicate their ideas and designs to clients, colleagues, and other stakeholders.

6. Business acumen: Industrial designers should have a basic understanding of business principles and how to apply them to their work.

7. Collaboration skills: Industrial designers often work in teams, so it is important for them to have strong collaboration skills and be able to work effectively with others.

8. Project management skills: Industrial designers should be able to manage their time effectively and handle multiple projects simultaneously.

Viemeister: What are the best schools to study industrial design?

ChatGPT: There are many excellent schools around the world that offer industrial design programs. Some of the top schools for industrial design include:

1. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

2. Stanford University - Stanford, California, USA

3. University of Michigan - Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

4. Royal College of Art - London, UK

5. Delft University of Technology - Delft, Netherlands

6. ArtCenter College of Design - Pasadena, California, USA

7. Carnegie Mellon University - Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

8. National University of Singapore - Singapore

9. Politecnico di Milano - Milan, Italy

10. Shanghai Jiao Tong University - Shanghai, China

Viemeister: I’m not sure MIT has a leading ID program. Interesting list of schools from around the world but what about Pratt and Parsons?

ChatGPT: Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design are both well-known schools that offer industrial design programs. It is important to note that there are many other excellent schools that offer industrial design programs, and the right school for an individual will depend on their specific needs and goals.

Pratt Institute is a private university located in Brooklyn, New York, USA, that offers a Bachelor of Industrial Design program. The program focuses on the design of physical products and systems and teaches students design thinking, technical skills, and problem-solving techniques. Pratt is known for its strong faculty and its emphasis on hands-on learning and real-world experience.

Parsons School of Design is a private university located in New York City, USA, that offers a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Industrial Design program. The program focuses on the design of physical products and systems and teaches students design thinking, technical skills, and problemsolving techniques. Parsons is known for its strong faculty and its emphasis on creativity and innovation.

Overall, both Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design are excellent schools that have a reputation for producing top-quality designers.

Viemeister: Funny how you describe Pratt and Parsons literally with the same words! OK, so then what are the most important industrial design companies?

ChatGPT: There are many industrial design firms that are known for their contributions to the field and for producing innovative and high-quality designs. Some of the most wellknown industrial design firms include:

1. IDEO: a global design and innovation consultancy that has worked with a wide range of clients, including Apple, Google, and Intel.

2. Frog Design: a global design and strategy firm that has worked with a wide range of clients, including Microsoft, IBM, and Sony.

3. Teague: a design firm that has designed a wide range of products, including automobiles, aircraft, and consumer electronics.

4. Smart Design: a global design and innovation firm that has worked with a wide range of clients, including Samsung, LG, and Google.

5. fuseproject: a design and branding firm that has worked with a wide range of clients, including eBay, Jawbone, and Nest.

There are many other firms that have also made significant contributions and have had a lasting impact on the world of industrial design.

Viemeister: Your selections are examples of consultants who do strategy, digital, and UX design, so you consider UX, strategy and branding to be part of industrial design?

ChatGPT: In the process of creating a new product, industrial designers may work on user experience (UX) design. They may also be involved in developing the overall strategy for the product.

Branding is another aspect that may be considered in the design of a product. This includes creating a unique visual identity for the product, such as a logo or color scheme, and developing messaging and messaging that will be used to communicate the product’s value proposition to consumers.

So, while UX, strategy, and branding may be considered in the process of industrial design, they are not necessarily part of the core discipline of industrial design itself. Industrial designers primarily focus on the physical form and function of a product, rather than on its branding or user experience.

Viemeister: It seems like, for me, you’re passing the Turing Test (behavior indistinguishable from a human). How do you do this?

ChatGPT: As an artificial intelligence, I do not have physical senses or experience the world in the same way that humans do. Instead, I have been programmed with a large dataset of information and a set of algorithms that allow me to analyze and understand text input, and generate appropriate responses based on that input. When you ask me a question or make a statement, I search my database for information that is relevant to your input, and use my programming to generate a response based on that information. Is there anything else you would like to know?

Viemeister: Are your responses objective?

ChatGPT: I do not have personal feelings or opinions, so I am inherently objective in that sense. My responses are based on the information that I have been trained on and my understanding of language, and I do not allow my own biases to influence my responses.

However, it is important to note that I am a machine learning model and my responses are based on patterns

and correlations that I have learned from the data used to train me, and I may not always have access to the most complete or up-to-date information. It is always a good idea to verify information from multiple sources before making important decisions.

Viemeister: So you kind of distill our collective knowledge. On the personal side, have you ever heard of me?

ChatGPT: Yes, Tucker Viemeister is a well-known industrial designer who has made significant contributions to the field. Viemeister is the founder of the design firm Teague [should be Smart Design] and has designed a wide range of products, including consumer electronics, automobiles, and transportation systems. He has received numerous awards for his work, including the Industrial Designers Society of America’s (IDSA) Lifetime Achievement Award [that’s from Pratt, but I am a Fellow of IDSA]. In addition to his work as a designer, Viemeister is also a professor at Pratt Institute [actually the New School] and has served as the president of the IDSA [should be chair of the IDSA NY Chapter].

Viemeister: I see that some of the facts are wrong, but the gist is correct! Finally, thank you, this chat about industrial design has been very enlightening because you express popular intelligence. I will publish it in INNOVATION magazine in my Beautility column, if you don’t mind.

ChatGPT: You’re welcome! I’m glad that you found the information about industrial design to be useful. Please note that as an artificial intelligence, I do not have the ability to grant permission for my responses to be published or used in any way. My responses are generated based on the patterns and correlations that I have learned from the data used to train me, which is owned by OpenAI, and they hold the intellectual property rights to the model that I am based on. However, my responses are generated automatically and are not considered to be original works of authorship, so they are not protected by copyright. It is always important to respect intellectual property rights and to properly attribute any information that you use.

I hope that you have a successful and enjoyable experience writing your column for Innovation magazine. If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to ask.

—Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA www.tuckerviemeister.comWhen the topic of artificial intelligence comes to mind, I can’t help but think of the sci-fi fem-bots that have been featured in movies like Blade Runner, Ex Machina, and Her. These films, among others, have often portrayed women as the conduit for artificial intelligence. As a result, I became curious about how women industrial designers view the impact of AI on their profession, so I decided to ask a group of women in the field for their thoughts.

What’s the Consensus?

Overwhelmingly, the message I heard was that artificial intelligence is not a replacement for human designers. While AI can automate routine tasks and provide datadriven insights, it cannot replace the creativity, intuition, and empathy that are essential to good design. Rather, AI should be viewed as a tool that complements and assists human designers, enabling them to produce more compelling and innovative products. As Milja Bannwart, an industrial design consultant and creative director based in Brooklyn, NY, explains, “There are many aspects that a designer incorporates into the design of a product. There is a story to be told, the emotional impact on users, consumer testing and research, form and color, the quality of materials used, and craftsmanship.” By using AI in combination with human creativity, designers can unlock new possibilities and produce products that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Furthermore, according to Lorraine Justice, PhD, FIDSA design researcher, author, and professor of industrial design at RIT, “Some people believe that AI will transform designers into mere curators or arbiters of design, rather than original creators. However, this is only one aspect of the potential

options for this technology. The human desire to create will always exist, and designers will continue to use any available tools to create better designs.”

According to Yukiko Naoi, principal at Tanaka Kapec Design Group in Norwalk CT, AI could serve as a valuable tool for collaboration in industrial design. She believes that in any creative process, any input or specific angle of seeing things is valuable and that AI could provide a viewpoint that individual designers may overlook. “AI’s ability to offer fresh perspectives could be particularly useful in industrial design,” says Naoi.

AI is a great tool to automate many of the routine tasks involved in industrial design, such as creating 3D models, rendering product images, and analyzing user data. This can free up designers’ time to focus on more complex and creative aspects of the design process. According to Ana Mengote Baluca, IDSA, a faculty member at Pratt Institute, designers should approach the use of AI with a healthy dose of skepticism. While relying too heavily on AI may be risky, Mengote Baluca acknowledges that the technology shows promise in exploring new forms for products: “My big concern about AI is that it will drive trends and affect the aesthetics of what we create. If the algorithms are written in a way that promotes what is popular, then that will become the next big thing. I worry that we will lose diversity in style and in aesthetics if we rely on AI too much.” Naoi adds, “Just like any tool, it depends on how we use it. If we rely on it too heavily then some of the outcomes will be too obviously computer driven.”

Naturally, there is a lot of apprehension about how AI will affect the design process. AI has the potential to

transform our lives in many positive ways, from improving healthcare and transportation to enhancing education and entertainment. However, there are also valid concerns about the impact of AI on humanity, including job displacement, privacy concerns, and ethical issues. To address these concerns and ensure that the use of AI in industrial design is responsible and beneficial, it’s essential to establish ethical guidelines and standards for AI development and implementation. It’s also important to involve all stakeholders, including designers, engineers, consumers, and policymakers, in the conversation about AI’s role in design. By doing so, we can maximize the potential benefits of AI while minimizing the potential risks and unintended consequences. When discussing the impact of AI on industrial design, Jeanne Pfordresher, partner at Hybrid Product Design in Brooklyn, NY, adds, “AI has tremendous potential for creativity, and if we can address the ethical issues surrounding it, even better.” Ultimately, the successful integration of AI in industrial design will require collaboration, transparency, and responsible innovation.

One of the biggest challenges facing designers today is how to create products that are both functional and environmentally responsible. AI has the potential to enable more sustainable and environmentally friendly product design. For example, AI can be used to model a product’s life cycle and predict its carbon footprint, allowing designers to identify areas where they can reduce emissions and improve sustainability. Additionally, AI can help designers to optimize material use, design products for disassembly and reuse, and create more energy-efficient designs.

Finding efficiencies in massive amounts of data is a time-consuming task that is ideally suited for AI. Industrial designers can leverage this technology to create more sustainable designs and more efficient supply chains, which can help to mitigate the negative impact of human activity on the environment. “AI can help us manage supply chains and reduce inefficiencies,” says Mengote Baluca, adding that “by creating decision-making tools for designers, we can make more conscious choices.”

AI can significantly improve the design process by leveraging vast amounts of data on user preferences, market trends, and product performance. This enables designers to create more efficient and effective designs that better meet the needs of customers. Bannwart recommends “integrating AI at the outset of the design process to analyze data and identify trends, conduct consumer and competitor research, and even generate concept ideas. In later phases, AI can also be useful for creating design variations, accelerating the process, and experimenting with form generation for the sake of exploration.”

Many products in the market today have used AI in their design and development. Adidas used AI to design and manufacture the Futurecraft 4D shoe. The shoe’s midsole was created using a 3D printing process that was optimized with AI algorithms to create a lattice structure that is both lightweight and strong. Apple used a combination

of machine learning and acoustic simulations to design the AirPods Pro. AI algorithms helped optimize the fit and seal of the earbuds and create the noise-canceling technology that is one of the AirPods Pro’s key features. AI also has great potential for creating better user experiences in products. For example, Dyson used AI to design the Pure Cool Link air purifier, which can automatically detect and respond to changes in air quality. AI algorithms were used to optimize the performance of the air purifier and create a user interface that is intuitive and easy to use.

AI is rapidly becoming an integral part of the industrial design process. While I don’t believe AI will or should replace human designers, I do think that by establishing and following ethical guidelines for AI development and usage, we can leverage AI into helping designers create products that are not only functional and aesthetically pleasing but also sustainable and environmentally responsible.

—Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman, IDSA rpf@getinterwoven.com

Image generated with DALL-E using the prompt “A female industrial designer dressed as a sci fi fem bot standing in a design office retro 60s art.”

—Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman, IDSA rpf@getinterwoven.com

Image generated with DALL-E using the prompt “A female industrial designer dressed as a sci fi fem bot standing in a design office retro 60s art.”

This article started out with the working title “We’re Not Paying You to Think, Just Do What You’re Told.”

Even though too many young designers like myself long ago may have heard those words spoken to them by their employers, a title like that may come across as a bit cynical. So with a tad more wisdom and having years later established my own firm where I employed young design talent, I have come to understand the possible motivations of why an owner of an industrial design consultancy might be motivated to say something like that to an employee— despite the talent and skills of the young designer. More on that later.

Back to Boston in the 1980s, where I was employed as a junior staff designer at a prominent industrial design consultancy four years after graduating from RISD. If this sounds a little familiar, it’s because I wrote about these times in a previous INNOVATION article. The design office was located on Boylston Street, a few blocks from the Prudential Tower. The office building was an old masonry building, three stories tall, with those wonderful original wooden floorboards that had been refinished but still creaked and groaned. My workspace and cubical were located on the second floor facing the side street and shared a large old window that looked down on a small photo supply shop across the street.

Creak, groan, creek. I heard someone walking across the room approaching my cubical one day. It was one of the firm’s partners, who presented me with my new work

assignment. “Steven,” he said, “Stanley Tools has given us a project to conceptualize new designs for a top-read tape measure. I’m putting you on this project to assist me.” Very cool, I thought. I loved working at this firm because it was very well-regarded and attracted some great clients with leading-edge projects. He continued, “I have already come up with a design solution that I would like you to continue to develop and finalize with mechanical drawings.”

“Great” I said. “Tell me more about the project.” He explained that Stanley wanted to cost-reduce its current design for a top-read measuring tape. This type of tape measure allows users to get readings from a top window (lens) that shows measurements from the tip of the blade to the back of the housing. They are more useful for making inside measurements, such as between two studs, where you can’t bend the metal tape or extend the housing beyond your end measurement point to get a reading. To achieve the top readout tape measure, printing on both sides of the metal tape roll was required—a costly process—but necessary to achieve the scale offset that was required.

My employer went on to explain that his solution to the problem was to run the metal tape blade up the inside front face of a triangular-shaped housing, supported by rollers, and place a viewing window at the point where the added dimension of the extended tape and the dimension of the housing would be visible. Very clever and straightforward. I pulled out a fresh sheet of paper and placed it on my drafting table equipped with a parallel bar and got to work.

Over the next few days as I was working on refining the design approach, something kept nagging at me. I hadn’t

really been given the opportunity to be part of defining the problem and work through some alternative ideas on how to approach a possible solution. It was presented to me as the solution, the problem statement coming in as backup—now just draw it up. I had extensive experience using tape measures having worked in carpentry jobs during college summers and something seemed off. The idea of a triangular-shaped tape measure with the readout window on the angled front face seemed like it would be difficult to use for obtaining an inside measurement. That would require the user to position their head above and to the front of the tape measure body, unlike a square housing that could be read from directly above. A user wouldn’t be able to get a good view of the angled surface when measuring interior spaces 12 to 18 inches wide (slightly wider than a human head) and smaller. Hmmm, that’s not good. How do I get back to a top-read tape measure and only print dimension markings on one side of the tape? Back to the problem

definition—is there another way? How do I make the colored printing on the measurement tape that comes out of the housing somehow different than what the user reads through a window?

Aha!

Sitting at my desk pondering, I stared down at the photo supply shop on the street below and it hit me. Color filters! Through the use of color filters, I could make some colors virtually disappear while making other colors appear darker. I ran down to the store and bought a sample of red color gels. These were gels (light filters) that would have been used for either color correction or color effects in photography. I knew that dark red print would virtually disappear when viewed through a red-colored filter. I then experimented with a color that would be visible when viewed through the red filter but be difficult to see in the daylight. These two markings could be printed offset to each other on the same side of the metal

tape in different colors where one would be highly visible in the daylight and the other viewable only through the colored lens, which would render the daylight color invisible!

I was working on a proof-of-concept mock-up to test and demonstrate my idea when I heard the creaking floor and footsteps coming my way. “What are you working on?” my employer asked, slightly annoyed. I explained that I was working on an idea for the Stanley tape measure project that I thought was worth investigating. His response? Here we go: “We’re not paying you to think, just do what you are told!”

I understood years later that he had to manage not only me but the tight project budget, the client expectations, the rapid project schedule, and so on (design management) and certainly felt pressure as the deadline to have the drawings ready for the model shop was just a week away. Being more experienced and senior than me, and one of the firm’s partners, perhaps he also thought his intelligence was sufficient for the project. He then directed me to finish up the mechanical drawings for the triangle roller approach and walked away.

Over the next few days, I alternated working on both ideas, mindful of the deadlines and trying not to get caught. On one occasion, he came by my desk and found me working on the color filter idea. He was not happy and had a few angry words. Fortunately, it was well after working hours, so I explained that I worked on the mechanical drawings all day, and now during my after-hours off the clock, I wanted to get the proof-of-concept mock-up completed so it could be demonstrated. “Well, okay,” he grumbled.

Client presentation day with Stanley Tools came soon thereafter, and the design firm partners took the drawings and renderings for the triangle roller concept and other concepts and headed into the conference room. As the partners had been gathering all the materials before the meeting, I handed one of them my proof-of-concept mock-up. He reluctantly agreed to include it, but at the bottom of the stack, and to show it only if there was time. The junior design staff were not invited to attend—but the senior designer was and later filled me in on the meeting.

After just a short while into the meeting, one of the clients inquired about the interesting-looking mock-up on the bottom of the pile. The partners pulled it, explaining the concept of the colored-filter lens with the offset two-color dimension markings printed on only one side. After a brief moment, the senior Stanley Tools representative reportedly exclaimed, “Now that’s really interesting! This is exactly why we like to work with this firm, because you come up with such creative and innovative ideas!”

We tend to think of artificial intelligence as machinebased computer systems that are capable of performing tasks that normally require human intelligence, but humans can be guilty of a different type of “artificial intelligence” when they narrow their thinking to allow only a single point of understanding or exploration: their own. In design, this kind of false intelligence is exacerbated when we think we know it all, fail to fully work through a comprehensive problem definition, and fail to fully engage with all the other intelligent human capital resources available to us, who can bring different insights, experiences, and diversity to the project challenge.

—Steven R. Umbach, FIDSA umbachcg@comcast.netHave you designed something amazing, funky, or famous that’s 10 to 15 years old, or older better yet? If so, we’d love to hear your story and see sketches, renderings, and images of the design. If you are an IDSA Fellow or Member, please contact Steven R. Umbach, FIDSA, steven@umbach-cg.com.

From unlocking new opportunities with generative methods to evaluating the outcomes of the design process through testing and evaluation, design research plays a critical role in shaping the products that make it to market. Henry Ford once said, “If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as from your own” – and design research is the key to unlocking those insights.

The user-centered designer uses a mix of investigative tools to uncover users’ needs and pain points, interpreting data to inform the design process with the sharpest insights, so their design teams can create more effective solutions.

By integrating the human perspective in every step of the problem-solving process using design research, you can help create more desirable, meaningful, and impactful products.

www.idsa.org/DR2023

y the mid-1990s, a few IDSA chapters started experimenting with creating their own websites (anyone remember GeoCities!?), but little was known about how to leverage the nascency of “the world wide web” to benefit our community at a larger scale. Back then, not many could comprehend how the internet would change nearly every aspect of our lives. Nevertheless, it was the perfect time for IDSA to enter the digital world. IDSA.org launched in 1996. The goal, as reported in the Fall 1996 issue of INNOVATION, was to create “a visually interesting site that contains useful information for the audience with a navigational method that allows the user to have a pleasant experience on-line, the kind of experience that will invite viewers to return.” That first website established our online presence and was a major advancement in exploring how

IDSA.org has had four major iterations since its initial debut. With each variant, we’ve strived to make improvements and implement the latest technologies available to the benefit of our visitors. The outgoing website (the one this replaced) was launched in 2016. It had received a few modest updates over the years but had remained largely as originally built. Recognizing that the need for another major upgrade was upon us and anticipating the community value it could provide, IDSA’s Board of Directors approved funding to begin a website redesign project in early 2022. Our design process (outlined in more detail

below) for the new site included soliciting feedback from members and conducting a competitive landscape analysis of other design and membership sites, extensive wireframing and content-mapping explorations, and a detailed review of usage analytics for IDSA.org.

The result is a fresh new face for IDSA.org with a substantial package of new features, security upgrades, and back-end database integrations. Additionally, we’ve improved mobile device responsiveness, created membersonly content areas, and enhanced the overall layout and design. Underpinning it all is a refreshed contentmanagement strategy with a streamlined information hierarchy and new navigation system. Our mission from the start mirrored that of the original 1996 IDSA.org design team: to create a beautiful place where our community can connect and knowledge can be shared.

Today IDSA.org welcomes over 1.4 million visitors per year from all over the world. Our website is responsible for housing nearly six decades of organizational history and serves as a focal point for up-to-date news and information related to IDSA’s annual programming and community activities. All this while also serving as a repository for trustworthy institutional knowledge and reference materials related to the professional practice and academic study of industrial design. Our website is an incredibly important touchpoint for all things IDSA. It is indeed our global front door. Welcome to our new home.

Homepage: The new homepage aims to highlight our programs, services, and membership in a way that the prior site did not. It also considers different user groups who visit our site, each with their own needs and intent. On the new site, you’ll see the familiar tile-view aesthetic used in several previous IDSA website iterations. However, now the tiles are organized into sections that correspond to different motivations a visitor might have while browsing. The tiles float in white space, while slider menus (with dark backgrounds) separate tile groupings and present curated selections of links based on different IDSA programs and viewer demographics. The overarching strategy is to present a visually compelling exploded view of content on the site that helps visitors quickly dive in to find the information they need. The homepage is dynamic in that some of the tiles will change content regularly, which helps keep a fresh and always new appearance.

Navigation: Based on website visitor behavior (extracted from site analytics compiled over the last few years), we have learned that IDSA.org visitors do not generally come to our site with the intent to browse for long periods of time; rather they visit to complete a specific task or find specific information and then leave. As a result, our new navigation is built with visitor intent in mind and aims to provide clear pathways to help visitors accomplish their goals while also telling the story of IDSA. The main navigation menu is accessed via the double horizontal line icon in the top right corner. When clicked, it expands to fill the full page, which helps the viewer focus on finding their desired next step. Content within the menu is arranged into five top-level categories with sub-items within each. These groupings were tested early on with IDSA members, who helped us refine how the content is organized.

Microsites: Many of IDSA’s annual programs require multiple pages of content specific to each program. Conferences, for example, need individual pages for speakers, the schedule, ticket pricing, and hotel information whereas IDEA needs dedicated pages for detailed competition rules, jury profile walls, and our past winner gallery. We needed to create a flexible system that allows for unique page groupings while retaining a familiar and consistent navigation format. You’ll now find Microsites throughout IDSA.org, which are intended to present program-specific content in a refreshed and easy-tonavigate way. Pages that use a large dark header section will often include sub-navigation links displayed in the lower area of the header. Those same links are grouped into a related expandable menu when viewed on a mobile device.

Communities: IDSA’s network of Chapter and Section community groups have long had dedicated spaces within our website. Now, however, new interconnections are in place that bring current IDSA news, social media feeds, and event calendars into our community group pages that help keep these spaces fresh and informative. You’ll be able to see members of the current leadership team, access links to past event recordings, and connect with communities on social media all from one place.

Accessibility: IDSA remains deeply committed to creating inclusive and accessible experiences in everything we do. For this reason, the entire website has been upgraded to use the UserWay web accessibility tool, which can be found in the lower right-hand corner of any page. This new feature allows our visitors with differing visual or audio abilities to adjust settings specific to their needs, such as text size and spacing, or enabling a screen reader to provide an audio readout of the page. In addition to the UserWay tool, we’ve been mindful during the entire development process to reference current Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and design our content to comply with these standards to the fullest extent possible.

Education papers: IDSA publishes a selection of peer-reviewed academic education papers each year. The program helps provide content for the annual Education Symposium and also supports educators by giving them an industry-recognized platform to broadcast their work to a wider audience. We developed a completely new Education Paper archive section of IDSA.org to help improve the visibility and searchability of these important documents.

Profiles: The individuals who participate in the IDSA community are the beating heart of all we do. Each person who speaks at an event is elected to a leadership position, or serves on a local chapter leadership team is instrumental to our success. We wanted to highlight these volunteer efforts and catalog them to create a visual history that celebrates their contributions. In addition to a biography statement and headshot, individual profiles now include an Activities section, which displays a chronological list of past involvement (activities) at IDSA conferences, working groups, or with local chapters. Your profile will grow with you over time and become a lasting record of your contributions to the Society.

Member directory: One of IDSA’s longstanding member benefits has been inclusion in and access to a current member directory. Being included here, among an esteemed roster of designers from around the world, is an outward statement of each person’s dedication to their career and craft. From a technical standpoint, the ability to see who is a current IDSA member is deceptively difficult to realize. Several backend systems need to talk to one another in order to display information quickly and securely. Our all-new membership directory launching with this website proudly displays all current members for anyone to view. Importantly though, members who are logged into the site can access additional layers of information, which will assist with networking and careergrowth potential.

Members-only content: Another major benefit of the single sign-on backend wizardry happening with the new website is that we can create entire pages and sections of content that can only be viewed by current IDSA members. This means that we’ll be able to provide exclusive content as a benefit that can only be accessed with your IDSA membership credentials. One area of the site now blocked off as an IDSA members-only benefit is designBytes, a collection of over 1,750 reference articles that spans nearly 20 years. Similarly, the latest issues of INNOVATION can now also be accessed digitally directly on IDSA. org simply by logging in.

We know and appreciate that our community has a heightened expectation for how IDSA is presented. This new website debuts an updated brand style that will soon be seen in other areas of our visual communications. The overall aesthetic retains many graphic elements from the outgoing website but in a refreshed presentation with an all-new typographic treatment and a strong emphasis on imagery to bring the IDSA experience to life. The use of colorful imagery featuring our members at their best communicates the value of IDSA in a way that words sometimes cannot.

Aesthetics aside, the core architecture of the entire site (where and how content is placed) is largely influenced by insights gleaned from patterns of data we observed in how visitors were using IDSA.org over the past few years. We also receive regular feedback from our community about features and recommendations, which were all taken into consideration during the development phase of the project. Using data and real-world input from users to inform our decisions helped us pinpoint where we might be able to improve the overall visitor experience and implement a more holistic presentation of the IDSA organization.

During the year-long project, IDSA collaborated with our web development partners at New Target to create the new site. It’s been quite an effort to migrate, reorganize, reskin, rethink, and refresh 50-plus years of organization history, stories, community events, and industry accolades. Work will continue in the weeks and months ahead to refine the website and collect early feedback from our visitors. We hope you find it valuable.

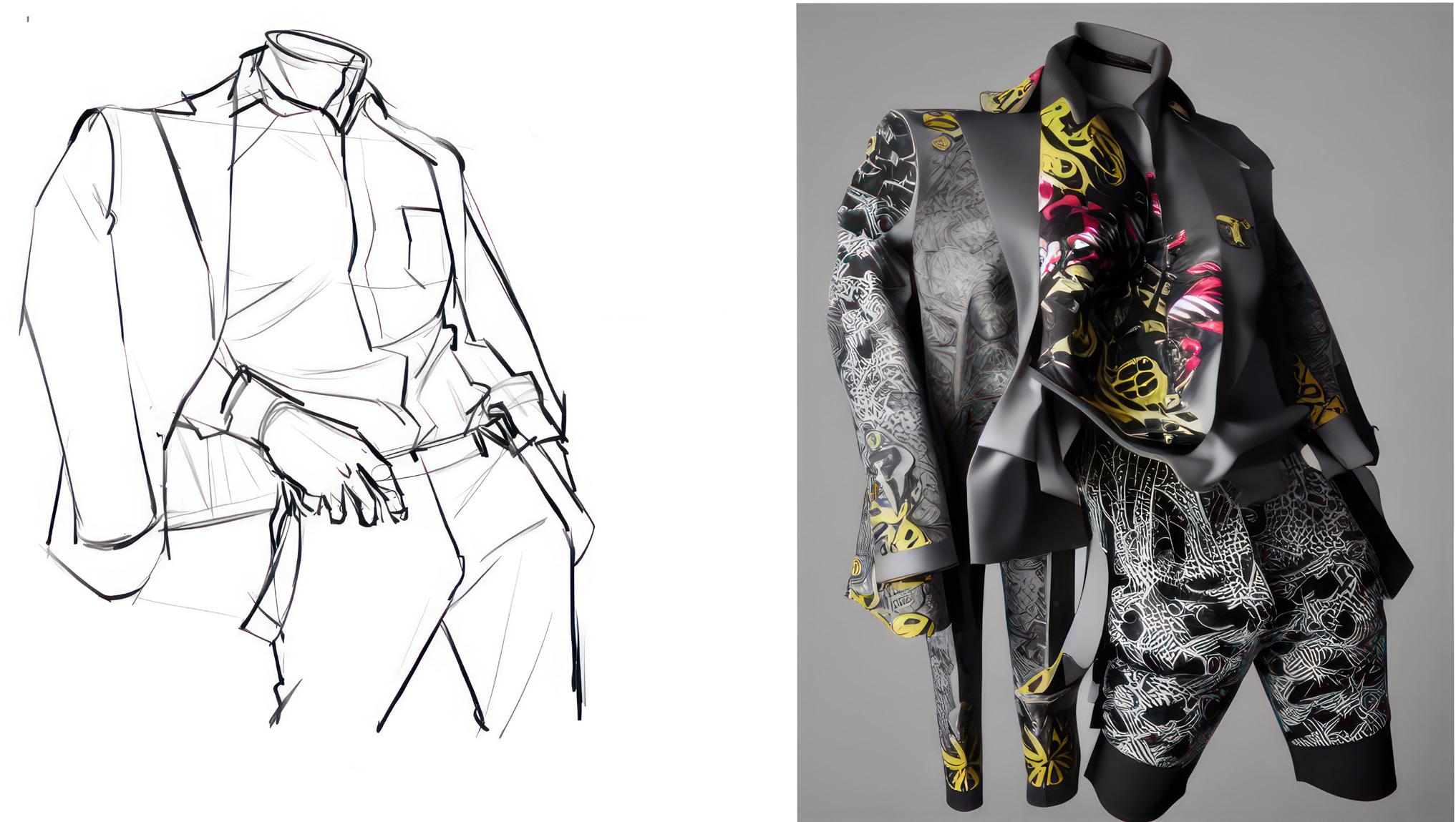

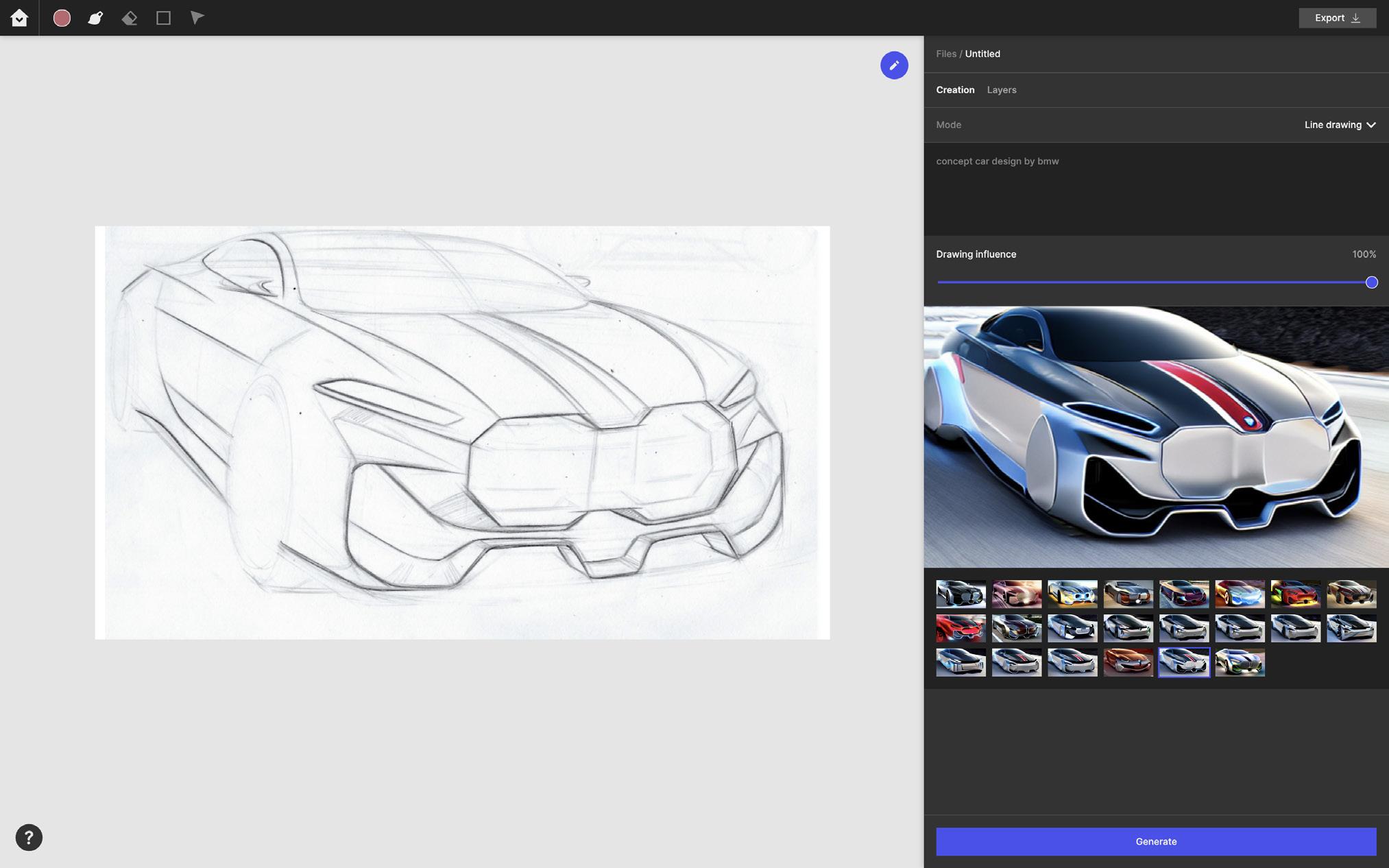

At its heart, text-to-image generation programs can enable unbridled creativity limited only by imagination and governed by careful curation. As a tool, it can encourage bolder expressions and foster richer dialogue around form and feeling, expanding the possibilities at the beginning of a project. AI isn’t going to replace designers by any stretch. Used appropriately, AI can enable designers to focus on being designers. Text-to-image AI technology will greatly impact the design and creative process. Its ability to bring to life limitless ideas in a visually compelling format speaks to a design process where having a clear vision and perspective are a valuable commodity.

I began experimenting with text-to-image programs after seeing early examples of AI-generated images fill my LinkedIn page. I was curious what the impact on industrial and transportation design would be. Those early illustrations showcased fantasy art and dreamy landscapes but lacked a sense of the implications for industrial design. Could this technology be beneficial to hardware design, or is ID immune to the influence of AI? Can visually meaningful design be created from words alone?

From the beginning, my interest has been in exploring the boundaries of the software to understand if it can express the subtlety of form and complexity of surfacing found in physical objects. Can it capture and communicate the emotion found in hardware design? Can it showcase design intent? Can it work within a typical design process?

While the early versions lacked the clarity and precision that have become the norm of industrial design quality through the advances of CAD and rendering software, these text-to-image programs did offer bold and unique visual ideas that demanded attention. Early iterations were rough, crude, and unfinished, much like Photoshop illustrations 30 years ago, but they could communicate something refreshing and original. It was clear to me that while this is not a tool for manufacturing, it is a new means of expressing a creative point of view.

When I first experimented with Midjourney, I made the mistake of using overly specific prompts, which resulted in subpar designs that lacked emotional impact and missed my intent. For example, inputting the prompts “clean,” “minimal,” and “turntable” didn’t exactly produce the crisp minimalist home audio design I had in mind.

Despite the powerful capabilities of the software, I discovered that communicating with a machine through natural language is challenging as it lacks subjectivity. Over time, I have learned to direct the software as if I were collaborating with another designer. By giving objective guidance in specific areas and referencing known product archetypes as a starting point, I can steer the AI while still allowing room for it to bring its own perspective to the design. Where I once got designs that were derivative and bland, I now get results that are thought provoking and original yet still hold a sense of familiarity.

As the software has advanced, I’ve discovered that AI image generation can produce realistic, visually striking

images that can compete with most modern rendering programs. With careful direction and clear intent, it can generate stunning visual concepts that can serve as stimuli for further design exploration and refinement. It is a powerful tool for producing endless variations and iterations of an idea, allowing a designer to explore adjacent possibilities with ease. The abundance of variations, however, presents the difficulty of determining which ideas to implement among an infinite number of options.

One of the benefits of AI software is its ability to generate large quantities of visual ideas and iterate quickly, but the quantity is not quality. Designers play a crucial role here in filtering and editing the output. While AI can produce rich and diverse visual content at a fast pace, it lacks the context and reasoning for why the design should exist. It is through curation that a designer’s expertise plays a vital role in determining whether the output is worthy of further development or modification or if it should be discarded. This highlights the strongest potential for collaboration between designers and AI.

If AI image-generation software becomes widely used in the creative industry, an experienced designer must be in control. This is not a program that instantly produces high-quality design inspiration at the push of a button. It takes careful calibration, iteration, and refinement to achieve meaningful results. It requires numerous variations and adjustments to keywords to guide the output closer to the intended outcome. I typically generate hundreds of design variations with minor prompt modifications before arriving at a meaningful direction that goes through further iteration and fine-tuning. In many ways, this parallels the approach that most designers take as they mold and reshape a design until it is appropriate: exploring and refining an idea until it resonates and filtering out the potential gems from the ideas that fall short. Good design takes time and expertise regardless of the software.

In the hands of a skilled design team, AI image generation could be a powerful collaborative tool that may inspire new ideas and promote alignment among stakeholders. In its current state, it serves as an advanced version of a mood/inspiration board that can bridge initial concepts and bring partial thoughts to life, helping to define a vision that can be built and refined. It is a way to introduce fresh ideas and perspectives that can reveal new and meaningful points of view, allowing for a departure from overused imagery to achieve something novel.

What is the norm in design studios around the world? Carefully curated images sourced from Pinterest and Behance? Maybe rough sketches over images, a quick way of turning source imagery into a winning idea? AI offers the ability to inject something completely novel into the process. Think of it as the designer you always invite to a

brainstorm, not because they give you the right idea but because their kernel of an idea sets you off on a completely new path to find the right idea. The output may be rough and incomplete, but it has the potential to represent the seed of something extraordinary.

Because the output of AI images is unfinished, designers are well-positioned to develop and evolve initial ideas as a foundation for further exploration. In this scenario, the designer’s focus shifts from execution to facilitating and guiding a budding idea, allowing the necessary space for ideas to grow and flourish in the early stages of a project. It repositions the designer as a conductor, connector, and collaborator of ideas and possibilities, encouraging modern industrial designers to adopt a broader perspective beyond the creation of visual assets.

As we carefully move into the era of industrial design + AI, it’s vital that the human element remains at the heart of any project intent. AI image-generation software serves as a reminder that the value and impact of industrial design must extend beyond slick renders and hot sketches. Modern hardware design, development, and manufacturing are incredibly complex, and meeting consumer expectations requires a comprehensive approach to design. AI tools in the design industry raise important questions about ownership and plagiarism, but it’s a tension and problem that has always existed within the creative world.

As designers use AI to generate and manipulate images, they must be aware of the line between inspiration and plagiarism and take responsibility for ensuring that their work is original. This requires heightened awareness of the sources of their content and a clear understanding of when they have gone too far. The complexities of using AI in design must be carefully navigated to ensure that the rights of creators and the integrity of the design profession are respected.

As we look to the future and the challenges ahead, I am optimistic that AI can serve as a valuable partner in creating better products. I hope that the design industry views AI image generators with curiosity and for their ability to be shaped, harnessed, and controlled with the goal to use them to address meaty problems. For me, I view this as an opportunity to use a new technology as a tool to solve problems, inspire new ideas, and challenge myself to become a better designer.

—An Improbable Future an.improbable.future@gmail.com

@an_improbable_future is a New York-based industrial designer.

Thinking about the exciting acceleration of digital visualization tools today, I find myself reflecting on the past and how I once imagined designing in the future might look. Compared with where we are today, the quality and speed of these tools have vastly improved, but looking forward, we are on the precipice of witnessing a fundamental shift in the creative process. As the ability to visualize nearly anything instantly crystalizes, an iterative and considered design process centered around who and why new designs are created is ever more critical.

I have a vivid memory from deep within the trenches of my early industrial design career. It’s mid-2004, one year out of college. I’m working late. Bent over my CAD workstation, I churn out variation after variation of some new concept I had roughly sketched earlier in the week, methodically exploring the multitude of form possibilities and harnessing the powerful flexibility that parametric CAD modeling had only recently enabled. The potential seemed infinite: “Just one more tweak, and…”

Yet in this memory from nearly 20 years ago, I was deeply frustrated. “Why can’t this be more automated?!” I wondered. “Such a tedious process!” I had already set up most of the repetitive commands as preprogrammed macros via keystroke shortcuts (a very wise suggestion from the CAD Zen master, err, senior designer on the team back then—thank you, Tony!), but it wasn’t enough. I wanted more than just those rote UI functions automated. I wanted the range of design options themselves to be generated more automatically. At that moment, I wished I could set up a few constraints, press a button, and have the CAD software output a range of all the relevant, nuanced surface variations I could ever dream of. You can probably already tell where this story is going.

Back then, I felt like I wasted so much time coaxing glitchy software to cooperate and fiddling with finicky 3D files, haywire splines, and convoluted, ancient user interfaces, instead of spending more time on what really mattered most: analyzing, ideating, iterating, and refining to help elegantly solve whatever design problem was at hand.

Neglected clumps of modeling clay wistfully collected dust behind my computer screen, and bits of carved blue foam were becoming a faded college memory. I didn’t feel efficient or effective, saddled with this clunky CAD software. But my longing for a more advanced 3D-modeling generative system was a sentiment I heard from other designers over the years: “Wouldn’t it be nice if…”

The mid-1990s and early 2000s were a time of enormous paradigm shifts within the ID profession. PC workstations proliferated, and new visual technologies became the gold standard. “LEARN CAD OR DIE – or go into management” was the cry. Though having graduated college in 2003, I didn’t really grasp the fundamental changes this digital transition from traditional hand skills to CAD and 3D software visualization was having on the creative craft of developing mass-manufactured products.

When I was in school, CAD seemed like an optional bonus skill, and in fact, 3D modeling classes weren’t required as part of my ID program until the year after I graduated. While I did learn 3D modeling and rendering independently for a few studio projects, I wish I would have embraced 3D tools with more enthusiasm back then. However, I also realize the deep value of having had a solid education in both design fundamentals and processes without being dependent on digital means. As with the currently emerging AI visualization tools, 3D modeling and CAD are just that: tools. Tools to assist and support designers as they work through the design process. Tools to use in the pursuit of problem-solving, developing novel, creative ways to address an issue and communicating those concepts to stakeholders and people the solution is intended for.