Hello and welcome to the first issue of IATEFL Voices for 2025. A very happy new year to you all from the IATEFL Voices team. I hope that the start of this new year has been a peaceful one. As I write this, I am reflecting on 2024, which is fast coming to a close, a year which has seen an increase in conflict around the world. In our first feature, Mohamed Yousif Abdalla and Lubna Hassan Elatta reflect on the war in the Sudan and what it is like to teach in a war zone. While our news is full of reports from The Palestinian Territories and Ukraine, little is reported about the ongoing war in the Republic of the Sudan. Thank you to both Mohamed and Lubna, and to Linda Ruas of the Global Issues SIG who helped put the article together, for providing this insight into what must be very difficult and harrowing conditions.

In our other feature articles, Meri Maroutian looks at the global phenomenon of the trafficking of native speaker English language teachers and asks when it will stop. Gillian Flaherty looks beyond the culture brief and discusses how to write materials for markets you have not worked in or visited before. Bruno Sousa returns to Voices to consider whether we still need to prevent taboo topics from being discussed in the classroom.

Jaber Kamali and Montaser Jassouma present research on what they learned about how to increase learning opportunities through group conferencing. Mark Nwaefido examines communicative language teaching from a critical perspective and considers whether it meets the needs of a typical language classroom in Kazakhstan.

Jack Hsiao returns to the theme of culture in his article, where he talks about including aspects of Chinese culture in his English language classroom. Finally, we hear from Terence McLean about the Flip and TILT teaching method, including examples of how this can be incorporated into your classroom.

And that leads nicely to our latest For the Classroom section, which includes two lesson plans. Elmira Shirinsokhan looks at sustainability using past modals, and Syed Naeem considers how songs can be used as a teaching tool.

Our regular Green IATEFL column is back and there is a double helping this issue. IATEFL President Aleksandra Popovski and Sabina Skenderovic report back on the recent ELT for Sustainability Conference they attended in Bosnia and Herzegovina. And Adrian Underhill provides advice on going public on your school’s green credentials.

The British Council is also back and we hear from Chris Cavey about the recent publication AI activities and resources for English language teachers, which looks at how teachers might use artificial intelligence in their classrooms.

We hear for the first time from Georgia Papamichailidou, the Chair of IATEFL’s Digital Committee on her experience of being Chair and a Trustee since taking over back in April. One thing that Georgia talks about is the IATEFL Live! shows, which you should definitely check out. There are reports from the Nationaal Congres Engels in the Netherlands, the Kazakhstani Association of English Language Teachers international conference, trauma-informed teaching from TESOL Türkiye and the IATEFL Poland international conference and webinar series, all in the From the Associates section.

With the IATEFL Conference in Edinburgh just around the corner, 2025 does have the potential to be a positive year, full of inclusion, peace and opportunity. I certainly hope it is wherever you may be. With best wishes,

Derek Philip-Xu Editor, IATEFL Voices editor@iatefl.org

Cover image by Kate Bielinski on Unsplash

At the Brighton Conference, Georgia Papamichailidou took over as Chair of the Digital Committee. In this edition of From the Trustees, Georgia discusses her role to date and what’s coming up over the next few months.

Let’s set the

Back in 2017, I attended my very first IATEFL Conference in Glasgow. While taking a break in a quiet corner of the Clyde Auditorium and Scottish Event Campus, I reflected on the immense effort behind planning such an impressive event. Fast forward seven years, and here I am, writing this article while taking a break from planning the IATEFL Themes Conference. This time as an IATEFL Trustee and Chair of the Digital Committee.

As a newly elected Trustee, I’m filled with excitement, curiosity and a deep commitment to share the work my Digital Committee and I are doing to offer digital spaces for knowledge-sharing, collaboration and sustainability within our ELT community.

When I took over the reins from my mentor, Shaun Wilden, my first goal was to honour the digital legacy he had built within IATEFL and to expand that strong foundation. Since my appointment in April, here is what has been in the works.

Uplifting the IATEFL Live! shows The IATEFL Live! shows are monthly livestream episodes broadcast on YouTube, Facebook and LinkedIn, providing a dedicated space for educators and industry experts to come together and showcase their expertise. Through these shows, we aim to offer a platform to anyone with valuable insights. This year, I designed the Live! shows around our Special Interest Groups (SIGs), with each month featuring a new focus. This allows the SIGs to showcase their work and invite meaningful discussions. The interaction between the guests and the audience is truly inspiring and I love the IATEFL Live! shows for being accessible, enriching and open to all! Be

sure to stay tuned for updates and the IATEFL Live! calendar.

Expanding the IATEFL Themes Conference

For those who cannot attend our annual in-person Conference, the Themes Conference is our digital solution! This annual online event highlights the most talked-about sessions from the Conference, based on delegates’ feedback and our SIG coordinators’ selections, to reflect the core themes in ELT. Our aim is to bring this experience to every corner of our global community, ensuring that IATEFL remains accessible to all. This year, we’ve expanded the number of sessions, broadened the variety of the topics and increased the range of our speakers. As I am writing this article before this year’s IATEFL Themes Conference, I can’t yet share how it went but I’m confident it will be fantastic!

Building a team of moderators

For those familiar with the IATEFL Live! shows, the names Anca and Niki might ring a bell! The Digital Committee and its moderators are the backbone of our digital community. Each moderator brings a unique voice ensuring our digital events are well-run, welcoming and interactive. Over the past six months, I have connected and talked to various people from different time zones; people interested in volunteering their time to be part of our digital journey to provide our IATEFL members the opportunity to grow. So, if you would like to be involved, please feel free to reach out!

Our IATEFL Vice President, Chris Graham, and I share a passion: making our world and classrooms greener! By laying the foundations for Green IATEFL, we’re designing a resource set to help teachers promote environmental awareness in the classroom. As Chair of the Digital Committee, I’m thrilled to support this initiative. Watch this space! Planning the in-person IATEFL Live! show in Edinburgh

Let’s not forget that next year, we’ll be meeting at the IATEFL Conference in Edinburgh! During the IATEFL Live! show, our online audience will get to meet speakers, sponsors, delegates and all the brilliant individuals who make the IATEFL Conference what it is! I am designing shows that will be educational, informative and will give you a taste of the Conference.

With our efforts with the Digital Committee, IATEFL is not only responding to our members’ evolving needs but also shaping the future of learning and development. Looking ahead, I am focused on expanding these initiatives, setting high standards and deepening my commitment to accessibility, inclusivity and fostering a culture of sustainability. I can’t wait to see it all come together! See you all online!

georgia@iatefl.org

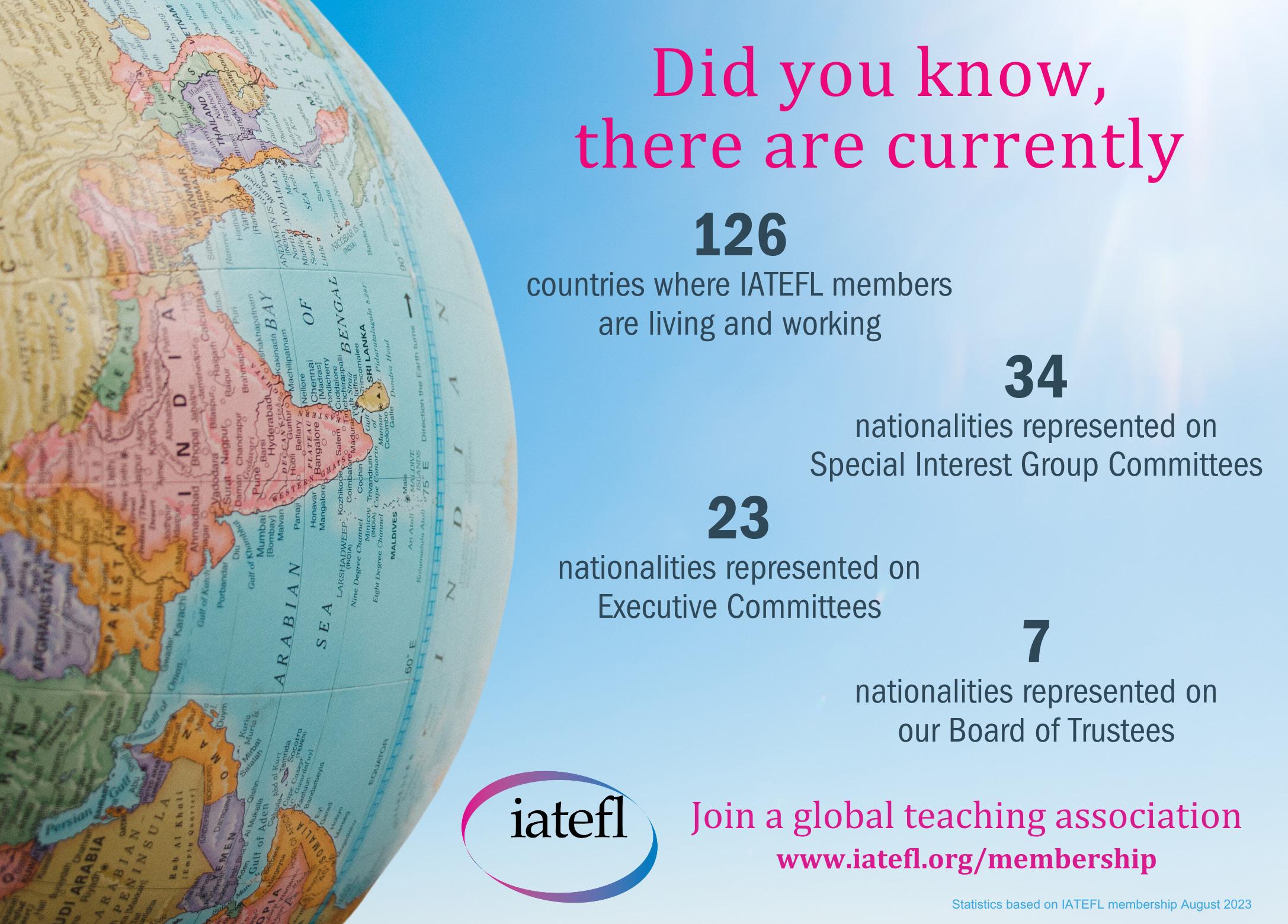

The International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language was founded in 1967.

Registered as a Charity: 1090853 Registered as a Company in England: 2531041

Disclaimer

Views expressed in the articles in Voices are not necessarily those of the Editor, of IATEFL or its staff or trustees.

Copyright Notice

Copyright for whole issue IATEFL 2024. IATEFL retains the right to reproduce part or all of this publication in other publications, including retail and online editions as well as on our websites.

Contributions to this publication remain the intellectual property of the authors. Any requests to reproduce a particular article should be sent to the relevant contributor and not IATEFL.

Articles which have first appeared in IATEFL publications must acknowledge the IATEFL publication as the original source of the article if reprinted elsewhere.

Aleksandra Popovski and Sabina Skenderovic report on the ELT for Sustainability Conference that was recently held in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The ELT for Sustainability Conference was held on 12 October in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the aim to bring together teachers from Bosnia and Herzegovina and the region to explore the critical intersection of ELT and SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). The conference was organised through a collaborative effort between Big Ben Centre from Tuzla and Symmetry Teacher Training from Skopje with the generous support of the British Council, Alfa d.d. and Alfa Naklada, exclusive distributors for Express Publishing, the US Embassy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, RELO Belgrade, SOL (Sharing One Language), and IATEFL as a strategic partner. The conference was opened by His Excellency, Julian Reilly, British Ambassador to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The conference programme focused on several key SDGs, with particular emphasis on quality education, environment protection, climate change action, and peace promotion. These topics were carefully chosen to demonstrate how language teaching can serve as a vehicle for raising awareness about crucial global issues. Sponsored by the event’s Platinum Sponsor, the British Council, Christopher Graham kicked off the day with a plenary on climate change and the actions that we as educators can and should take. His question – What exactly is sustainability and what role does the ELT community have in developing and maintaining it? – led to some interesting questions and discussions from the audience. Ivana Bokavshek, Alfa Naklada, focused on teaching green to grow green, i.e. how to make students more environmentally sensitive, but also how to adjust our teaching-self to educate new generations of students to grow and

Aleksandra Popovski is a teacher and teacher trainer with a strong passion for language education. Her interests include multimodality, incorporating visual arts into language teaching (graphic novels, street art, tattoos), exploring effective reading comprehension strategies, and creating original readers for her students. She is particularly interested in reading as a tool for exploring and discussing issues such as social (in)justice, diversity and inclusion with learners of English.

Sabina Skenderovic was born in Bosnia and Herzegovina. She has been teaching for over 15 years. She has an MA in the English Language and Literature. She has won prizes for innovative use of technology, a Superwoman of Solidarity Prize and was selected the person of the year in the field of education.

maintain their ecological responsibility. Daniel Xerri, University of Malta, shared his ideas and views on how to reflect on sustainable development through a glocal perspective and the potential of reflective thinking as a catalyst for change. George Kokolas, Express Publishing, introduced the conference participants to the world of positive education, a scientific, longimplemented educational framework in which teachers and students can flourish and find encouragement when they feel stuck or demotivated. Larisa KasumagićKafedžić, University of Sarajevo, explored the intersection of the SDGs and the need for learning approaches in language and culture education that empower, transform and humanise learning. The US English Language Fellow, Marissa Foti, shared some engaging activities with the audience to help them integrate SDGs into their classroom practice. All the speakers emphasised the growing importance of addressing global sustainability challenges within language education.

The conference ended on a positive note with a prize draw generously sponsored by SOL – Sharing One Language, Devon, UK. Two teachers from Bosnia and Herzegovina will attend SOL teacher training courses in Devon and Serbia, respectively.

More than 100 participants created a vibrant atmosphere for knowledge exchange and professional development. Teachers from various backgrounds shared their experiences and challenges in implementing sustainability-focused teaching practices,

contributing to a rich dialogue about the future of ELT. What made this conference particularly impactful was its timing, as educational institutions and organisations worldwide are increasingly recognising the importance of integrating sustainability into their teaching practices. IATEFL, with its Green IATEFL initiative, is one of the organisations that is fully aware of and recognises the urgent need for creating a space for discussing sustainability in language education, what opportunities and challenges lie ahead, and how we can approach and address them.

Looking ahead, the ELT for Sustainability Conference has laid foundations for future initiatives in sustainable language education in the region. While formal resolutions were not made (and that was not the purpose of the event), the conference established important connections between ELT professionals committed to incorporating sustainability principles into their teaching methods.

This professional development event, first of its kind in the region, highlighted how English language instruction can be enhanced to address current global challenges. The conference demonstrated that ELT professionals are increasingly ready to accept their role in promoting sustainable development through language education, and they are willing to become part of the movement for more sustainable practices in ELT and language education in general.

We hope that the ELT for Sustainability Conference will become a regular event in the region that would bring together English language teachers from around the world to share their experiences and expertise in sustainability in (English) language education.

We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.

Indigenous American proverb

aleksandra@iatefl.org

Adrian Underhill talks about how to achieve green credentials for your school in an edited version of an article that first appeared in Humanising Language Teaching (HLT) in December 2024

The school scene

The leadership of most schools want to act on climate change and wider issues of sustainability. They know their business has leverage and can make a difference, and that their staff and school community will support the school championing eco values.

Schools that do this visibly will command attention and allegiance, grow their community, draw in parents, sponsors, kids, local networks, influence teaching materials, and gradually influence syllabuses and exams, and eventually even ministries (!). Such schools gain fans not just customers, and act as compelling thought leaders for others.

Green content for learners

Much progress has been made on classroom resources, lesson plans, teacher strategies and a green learner syllabus. There is lively discussion through media and publications. IATEFL has launched Green IATEFL and the September/October 2024 issue of Voices (issue 300) is packed with ideas for action and reflection. Yes teachers need to act, and they are. But what about the schools they work for? It is not enough to encourage greening the class, that should be a natural outcome of a wider greening across the school, organisation or association.

Green content for the behaviour of schools themselves?

Well, schools face a real problem here, which is where to start, how to selfmeasure, what can be improved and how, how to prioritise, how to benchmark against standards, how to compare with others,

Adrian Underhill is a consultant to schools, and offers one- or two-week face-to-face teachers’ courses at Oxford University, IH London and Bell Cambridge, as well as online. His video series is available at www. macmillanenglish.com/pronunciationskills/, his blog at https://adrianunderhill. com/, and demonstration videos at www. macmillanenglish.com/pronunciationskills/ and on YouTube.

and how to make credible and audited claims through their school’s media that will turn heads, win hearts and promote reputational advantage. It is not enough to sit down and make lists of actions like paper saving, doing digital, cycling to work, recycling, power reduction, etc. though these are part of it. Nor is it enough for schools to rely on worthy environmental self-claims which are haphazard, unreliable and subjective, limited by your time constraints and blind spots. Just as schools cannot make serious claims to pedagogic excellence without an evidence-based audit from an external inspection scheme, so too the claims of impact reduction have little credibility unless backed by a recognised external auditor.

Most language organisations deal with learners in their local communities. Some especially in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, the US, etc. are study abroad institutions. The latter have the additional carbon impact of international travel, and since impact reduction of air travel is as yet unresolved, you have to keep that question boldly open, while forging ahead systematically and visibly on tracking and reducing impact across all the categories where you can make a difference, picking the low-hanging fruit immediately, and working toward the more challenging impacts as you develop the skills, momentum and a framework. And how do you do this?

The simple answer is to use one of the growing number of ready-made online frameworks designed for small organisations who want to act sustainably

and to demonstrate that they are doing so. These frameworks tell you what to measure, how to score yourself, how to make your improvements visible, and how to show the outside world your credible, benchmarked and objective scores. Using a ready-made measuring system is simpler and more robust than trying to invent a system yourself.

In this article, I introduce you to three such ready-made, online, sustainability auditing systems, in the hope of inspiring you to examine them and commit to working with one of them, or with something similar. I also reference two further schemes.

Two of these three ready-made frameworks are specifically for ELT schools, and one is for any small- or medium-sized enterprise. The first two are free to use and if later you want to join, there is a cost. The third is designed for an international organisation of schools, and though only members have access to it, I describe it here so you see how it works, and if you are part of a chain or association of schools, you might consider developing your own membership auditing system. But make sure it is measurable, credible, audited, and above all made public so that you too exert thought leadership throughout the industry community.

1 Green Standard Schools for ELT schools

2 BCorp for any small enterprise including schools

3 Environmental Sustainability Review for members of the International House World Organisation.

Overview of the three impact audit schemes

Green Standard Schools (GSS) greenstandardschools.org/ GSS includes guidelines to help ELT schools become more environmentally

sustainable. There are tools to measure the environmental impact of your school. Evaluation involves self-assessing but is accredited by an external panel. There is an option to join the GSS Association. Green Standard Schools has three aims: Provide policies

The first is to provide a set of policies and practices that schools can adopt and adhere to. You work through a selfassessment form consisting of 50 yes/ no questions covering language school activities that have environmental impact, such as energy and water consumption, purchasing, recycling, accommodation, food, travel, teaching, training, social activities, etc. You provide evidence to verify your answers and submit this for a free audit of your current policies and practices.

Award accreditation

Assessors award points for the answers given and for the evidence provided. They also give feedback on questions answered, including suggestions on how schools can improve their performance. Schools gaining 130/200 points can become members of the GSS association Those that don’t make it first time, which is quite natural, learn from the tailored feedback how to measure more accurately and credibly, and resubmit when ready. Develop pedagogical resources

The third aim is to design and provide materials to encourage integration of environmental content in language teaching and learning. These materials consist of lesson plans, videos, reading and other study resources, all provided free on the GSS website, app. greenstandardschools.org/public-lessonplans See the August 2024 issue of HLT for a full description Green Standard Schools.

bcorporation.uk/b-corp-certification/ BCorp measures social and environmental impact, since they are connected. There is a comprehensive matrix of specific points to work on, and guidance on how to measure and how to self-award points for measures (already) taken. Points are intended here as an objective measure of impact reduction and can be used for comparison or to show progress. The BCorp route map is about assessing your impact, comparing and improving.

Social and environmental impact is measured across these five interconnected impact areas.

Governance

Example: What portion of your

management job descriptions include evaluation on their performance with regard to corporate, social and environmental targets?

Workers

Example: What say do full-time workers have in the school’s company impact?

Community

Example: What percentage of management is from underrepresented populations? (plus diversity, equity, inclusion)

Environment

Example: Does your company monitor and record its universal waste production?

Customers

Example: How can customers verify that your school is improving its impact?

When you sign in to your dashboard, you’ll see the impact assessment page, showing these five categories, the number of questions in each and your current score. Choose those questions you are ready to work with. The question guides you as to how to measure. Your responses yield your baseline score against which to improve and see your progress, and to compare yourself and others.

This reveals actions with zero cost attached, i.e. quick wins with immediate score improvement to be gained, actions that are doable but need budgeting, actions you’ll leave for the moment, and those which do not apply. So, you quite quickly see the big picture of your impact, a baseline score which you can use internally or in promotion and planning.

When ready, you can evaluate your performance compared to the thousands of other businesses that use the impact assessment platform to identify, track and improve week by week.

Environmental Sustainability Review

ihworld.com/about/environmentalsustainability/

This consists of twelve self-review criteria, six things to do more of, and six to do less of (see below). You complete a guided self-review and submit for assessment, followed by further exploration of actions taken. The resulting audit is time-dated, and schools would repeat every two years to show further action and commitment to continuous improvement.

The six things you need to do more of include: educating students, encouraging sustainable behaviour, increasing community involvement, setting a food supply policy, setting sustainability requirements for suppliers, and

managing your sustainability strategy. The six things you need to do less of include: travel-related and negative impacts, energy consumption, singleuse consumables, waste and re-cycle, water consumption, and environmental footprint of new premises.

Against each of these twelve criteria, you state what actions you are taking, at which of these four stages you are currently, and:

❚ how you intend to act;

❚ how you are currently acting;

❚ how you have committed to quantifiable actions and measures; and

❚ how you have in place a total school strategy for documenting measures and effectiveness.

Then, you complete the online self-evaluation and submit. Staff at International House World Organisation assess the responses and then follow up with stakeholders in your school, developing evidence through interview/ discussion, documents, photos, videos and so on. When all this is completed, a short video or blog highlighting points of excellence is made and used to champion the school’s achievements within the industry and as widely as possible. Demonstrating significant action on eight of the criteria gains you a badge to use on media and communications

UNESCO www.unesco.org/en/educationsustainable-development/greeningfuture/schools

❚ a Green School Quality Standard covering School governance, Teaching and learning, Facilities and operation, and Community engagement;

❚ shows what a climate-ready green learning environment should offer; ❚ a useful thinking and planning tool; ❚ particular focus is on the school community and engagement.

If you want an audited impact rating, you can refer to their list of accreditation schemes aligned with this standard, or find your own. Certainly, you could use this in conjunction with any of the three audit schemes above.

Eco-schools

www.eco-schools.org.uk/

This has an early years focus and is UK-based, with activities and checklists for getting everyone involved. It has very

useful starting ideas and action checklists. It includes a simple ‘Count Your Carbon’ calculator. It is designed for nurseries, schools and colleges. It helps calculate, understand, reduce and track your carbon emissions. There is no external audit.

Note that some items in these impact audits will overlap with legal compliance (maybe 15 per cent?), which may be worth prioritising as they are (becoming) legal requirements.

Once you’ve looked at the five schemes listed here you will be better placed to discern between audit schemes, to see what help and guidance is available out there, what your own impact measurement

needs are, and which scheme can best walk you through the steps, help you make visible your school impact, measure improvements and make upbeat credible claims to the world.

The schemes differ in the detail they go into, the number of guiding steps they offer for measuring and for reducing impact, and the control you have over scoring points that will be meaningful to you, your staff and the community. That’s why I think it is important to look at several audit schemes prior to launching out.

This is a journey not only for school leaders but for an entire school staff and its community. When the organisation itself takes ongoing conspicuous and measurable action on its own behaviour, the entire staff can feel the encouragement of collective

commitment across the piece, and a worthwhile venture takes on a life of its own, offering some counterbalance to feelings of powerlessness. Be sure to engage staff from the first moments in an inclusive strategy rather than presenting a ready made plan. Ultimately, you will have a school with good transparent governance, an engaged staff, a higher purpose that brings people together in a unified endeavour, and something to show the world.

In a nutshell: engage school and community, make a verifiable difference, tell the world… and be part of the change.

adrian@aunderhill.co.uk

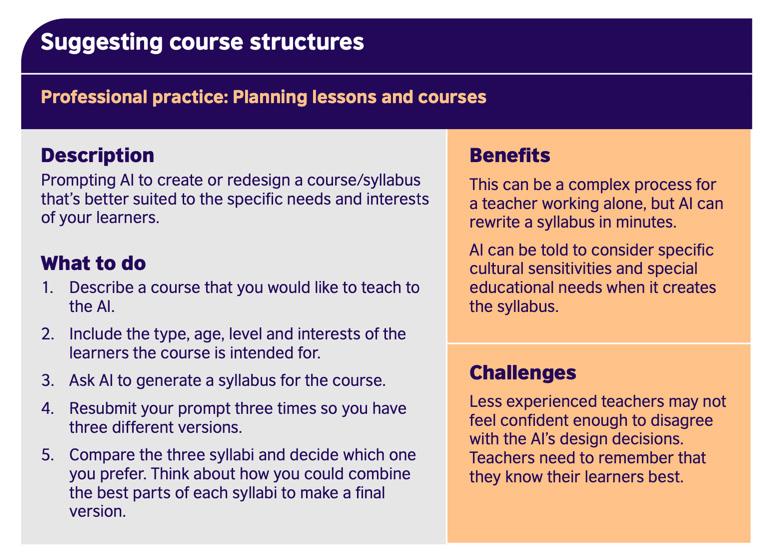

Chris Cavey is Broadcast and Media Lead, English and School Education at the British Council. Here he introduces AI activities and resources for English language teachers, a new publication helping teachers incorporate AI into their practice.

Among the many interesting findings in the British Council’s landmark 2023 report, Artificial intelligence and English language teaching: preparing for the future was evidence that English language teachers were enthusiastically embracing AI and using AI-powered tools for a range of tasks. Almost 80 per cent of teachers agreed that AI can help learners improve their skills and 65 per cent of teachers agreed that AI can plan effective lessons. Equally clear however, was the feeling that teachers have not received enough training, with only 20 per cent of teachers feeling sufficiently trained.

The report concluded that it would be useful to have a breakdown of language teacher activities and examine the ways that AI might be used to help teachers in each of those activities.

AI activities and resources

AI activities and resources for English language teachers is a response to this need. It identifies ten areas where teachers might use AI. These include:

❚ helping learners evaluate AI output;

❚ personalising and adapting materials;

❚ acting as a collaborator and mentor; and ❚ supporting teachers’ professional development.

For each of these ten areas, there is a choice of activities that teachers can try or adapt to their context. The activities are linked to the eleven professional practices of the British Council Teaching for Success CPD framework so that teachers can contextualise their AI use with their other CPD activity.

Each of the 43 activities includes stepby-step instructions to guide teachers but also includes sections on both benefits – a rationale for the use of AI in the context –

and challenges – a summary of potential risks for teachers to consider before using the activity (see, for example, Figure 1). These sections reinforce the importance of a considered approach to the use of AI tools by weighing up the advantages and mitigating against potential pitfalls.

Benefits

❚ AI’s capacity to generate lots of ideas, examples and text types in a fraction of a second can save teachers and learners time and help them focus.

❚ As a speaking partner, AI can be less stressful than speaking to another person – and will never get tired of interacting.

❚ AI enables teachers to personalise and localise content to match the culture and interests of their students.

Challenges

❚ Information generated by AI may not be factually accurate. Teachers should always check AI-generated text before sharing it with students.

❚ AI may have limited knowledge of some cultures and may produce material that is biased toward a particular culture, class or ideology. Again, teachers always need to check and select carefully.

❚ AI may not be culturally sensitive, for example in producing discussion questions on topics that may upset or cause offence.

❚ There may be a temptation for learners to over-rely on AI for producing language.

❚ Teachers must always be aware of which data should not be shared with AI – both in terms of any personal, identifying data and the use of copyright material.

To reinforce this idea that AI is not itself an expert teacher but a tool for teachers to use, AI Activities and Resources for English language teachers includes other sections to broaden teachers’ engagement with AI.

Guiding principles: There are five guiding principles that provide teachers with a checklist to refer to when considering their own use of AI.

Writing effective prompts: The right prompts are essential in getting the best outcomes from an AI tool. The more information you give about style, audience, length, format, context, etc., the better the results will be. A prompt template and a range of example prompts are provided to help teachers.

Further resources: A final section compiles a range of British Council reports, articles and resources from the TeachingEnglish website and elsewhere with further advice and guidance on risks and how to mitigate them.

The pace of development and the range of AI tools available can seem dizzying but English language teachers have proved to be among the most enthusiastic adopters of AI in education. AI Activities and Resources for English language teachers is another step from the British Council towards providing teachers with the knowledge and tools they need to ensure the best outcomes for their students.

TeachingEnglish@britishcouncil.org

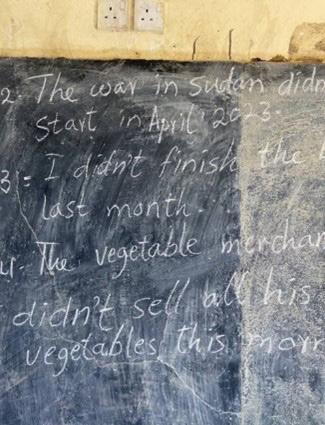

Mohamed Yousif Abdalla and Lubna Hassan Elatta wrote this article to show how teachers are teaching, in very challenging circumstances, during the war in the Sudan. It summarises the situation now, what teachers are doing, and how they are getting support. It has been put together with the help of Linda Ruas, joint coordinator of the Global Issues SIG, from WhatsApp messages and photos sent by Mohamed.

The bomb alert sounded. We knew the bombing would start again at any moment. My students immediately slid under the tables, a practised routine, which did not have much chance of protecting them from a direct hit. Suddenly, one of them started singing:Ten green bottles, sitting on the wall… The others joined in, one by one. It was all I could do to stop myself from crying. Another day, they started singing London’s burning, and soon changed this to ‘Khartoum’s burning’.

I have been teaching and training teachers for many years, and this is one of the most challenging, upsetting circumstances that I have ever found myself in. When the war started in April 2023 in Khartoum, many families were able to leave, by crowding onto buses, walking very long distances, risking being attacked on their way, queuing at the borders for many hours. I was not able to leave, as I needed to look after my parents who could not travel, and my area is one part of Khartoum where the fighting has been constant since the start of the war.

Mohamed Yousif Abdalla is Deputy Director of the Sudanese English Language Teaching Institute (SELTI) and has over 20 years’ experience of teaching in Sudan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. He is also a social and education activist and interpreter, and is on the board of the Sudan English Language Development Association (ELDA).

With a comprehensive skill set that encompasses language instruction, translation, leadership and community outreach through being President of the Sudan ELDA, Lubna Hassan Elatta continues to make a significant impact in the field of education, empowering individuals to reach their full potential and contributing to positive social change.

Sudan has been in a state of political instability for many years, and this affected its educational policies in a significant way. The Sudanese December 2018 revolution was the beginning of great political stability that could have advanced the country, especially education. Sadly, war broke out again in April 2023 and stopped all the progress.

Now, about 19 million children in Sudan are out of school. 10,400 schools have been closed completely in conflict-affected areas. All language teaching centres, educational institutes, universities, colleges and private and public schools have been affected and English language teachers suffer a lot.

Khartoum is far from safe. Many civilians have been killed, even inside their homes. My area is controlled by the rebels, and the army are trying to push them out. The rebels robbed our house, our vehicles, our money, our jewellery, banks, electronics – everything. They live by robbing, by threatening people at gun-point. If any civilian tries to defend their property, they are shot.

At first, we had no electricity. Food and water were very difficult to come by, and people risked their lives leaving their homes to search for some. There was little or no aid from international agencies as it was too dangerous for them to come to the city.

Everything stopped in the first two or three months. Then, little by little, over the past nine months, we have organised ourselves to help and support each other in the most terrible of circumstances. In times like these we have in Sudan a concept called ‘Takiyya’. It’s simply that people put all the money they have on the table, no matter how much it is. All the food is stored in one place. Then people form a committee to be responsible for managing all these resources. Food is cooked in one place and distributed fairly, based on the number of people in respective families. We have a group responsible for bringing water from the river by big tanks, directly to the houses. Another group goes shopping. There’s also a finance group, a medicine group, etc. We receive money from our relatives and friends who live and work abroad. These are the real backbone of the Takiyya.

In our schools, we don’t only teach academic subjects, but we also run group therapy sessions, as the children have been traumatised and experience nightmares due to the long period of the war. We hope this works. The children are really broken and scared all day. By attending our classes, especially English lessons, they have become less worried, at least during class.

English language classes re-started with three learners under the shade of a tree at my front gate. Now we have more than 200 students at different levels. I am now working with high school boys and

2023

Issue 290 2022

2022 2019 girls, and there are also ladies coming to the classes who are not students. They really like the idea of coming to class and learning English, as they have been locked at home doing nothing, and they call it ‘Time for a peaceful mind’. Recently, some of my students’ elder brothers and sisters have been coming to the classes too.

Some of our activities are related to the war. For example, we have been working on conditional grammar, but practising it by applying it to our hopes and plans, for example:

❚ When this war ends, I’ll live in a peaceful place.

❚ When this war ends, we’ll be happy with our family.

❚ When this war ends, I’ll live in a quiet place.

This helps with positive thinking.

One of the big challenges in teaching is not just convincing the parents to send their boys and girls to us at the school but how to overcome our own fears as teachers having to walk to the school (maybe only 7 minutes) – with the constant risks of being shot at or stopped and frisked by armed men.

One solution is for teachers to come together and support each other. The Sudan English Language Development Association (ELDA) is attempting to do this – again, in very difficult circumstances.

The situation changes daily; the Internet is very often cut off completely, teachers need to move anywhere they can find work to support their families, who are often suffering from trauma.

The British Council is helping with some online courses for teachers. Africa ELTA is helping, with the offer of webinars and free entrance to the Africa ELTA conference for Sudanese refugee teachers. We are very grateful to them and anyone else who can support us.

We do have some ongoing support in our Sudan ELDA WhatsApp group for members, with discussions about, for example, how to motivate learners and teachers, and presentations on understanding and helping learners with trauma, problem solving and requests for help. Finally, we are now putting together a simple online publication: Teaching in times of conflict, with articles from around the world, to support and help everyone.

lubnulia@gmail.com

Meri Maroutian outlines the ‘trafficking’ of native speaker English language teachers and asks when this practice will stop

Introduction

In the context provided in the article, the term ‘trafficking’ pertains to the systematic preference for English language teachers primarily from English-speaking or ‘inner circle’ countries – as defined by Kachru (2005) – being flown over to ‘outer circle’ countries to meet the market’s high demand of native speaker teachers. This practice underscores the belief that native speakers of English, particularly those from countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and sometimes Ireland and South Africa, are inherently superior

Meri Maroutian is the founding member of The Non Native Speaker. As an Armenian who has lived and studied mostly in Malaysia, America and Italy, Meri has become increasingly aware of the social injustices reserved for those who are forever perceived as ‘nonnative’ speakers of any given language.

teachers. Consequently, individuals from these countries are often favoured for teaching positions over candidates from other linguistic backgrounds or local teachers.

The English language teaching industry is growing exponentially as there is still a high demand for English teachers in both the

public and private sector worldwide, and it is showing no signs of slowing down. It is definitely a very competitive market, with teachers honing their niches and offering their expertise for business English classes, exam prep, young learners or English for advanced levels. This has opened a whole new job prospect for those teachers who want to work remotely or make ends meet with online classes, which allows them to be more flexible, teaching from anywhere in the world and at any hour.

In such a competitive and lucrative market, it is no wonder that so many are interested in creating a career for themselves or seeking new work opportunities that take them across land and seas. But what are the requirements for English language teachers nowadays? And who has the upper hand when it comes to getting picked for a job?

The allure of native speaker teachers: a deeper look

Rather than give a list of requirements for English language teachers in the current industry, we should take a step back and look at what is being advertised in the global market. Specifically, we should be paying more attention to teachers being advertised for the nationality that they hold, rather than their years of training and qualifications.

The high demand for native-speaking teachers who constitute a minority, is still being played as a competitive advantage for learners. Countless articles are being written with the sole purpose of recruiting native speakers for teaching jobs, promising a legitimate income source that can easily pay bills while providing free accommodation and a nomadic lifestyle. It all sounds extremely enticing and adventurous and with very little investment as no prior teaching experience is required apart from a level 5 TEFL certificate, in some cases.

The TEFL Academy is currently offering their online course at a discounted rate of €215 to complete in 168 hours, self-paced and with support from tutors. These courses are easily accessible to the public but are more advantageous for some than for others. No mention of nationality or place of birth up until this point, but when we look at the job search and availabilities posted on the same website, here’s what it can look like. This one is from Seoul ESL Consulting, Korea, dated 2023.

You must have citizenship and a valid passport from one of the following English-speaking countries: Australia, Britain, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, United States. You must have a bachelor’s level degree, or greater, from an accredited university or college-all majors and disciplines are accepted but two year college graduates are not allowed to obtain a work visa. (http://www.seoulesl.com/ teachinkorea/qualification.asp) They continue as follows:

Our schools and academies have solid curriculums and offer well-organized teaching materials as well. Due to these curriculums, teaching materials, and teacher training programs, even teachers with little or no experience will be able to adapt quickly to the life of an English teacher. We have placed

numerous native English teachers in schools all around Korea for the past ten years, and have developed a network of excellent schools through years of experience.

The ideology of the native speaker teacher model being superior is still being perpetuated through these job ads, and what is worse is that with respected organisations allowing this to happen and promoting it on their websites, it comes as no surprise that many people from the right anglophone countries are using these schemes to their advantage.

addressing

The message is clear, and these global organisations are not doing much to prevent stereotypical biases from coming in the way of professional teachers, with master’s degrees in education and certificates for teaching English to speakers of other languages, to find their place in the market.

This was also confirmed by English language teacher (ELT) professionals from Ireland, Canada, Vietnam, Guatemala, Australia, Poland, France, Scotland, Argentina and Italy, with whom I had the pleasure of recording a live series of interviews on the topic of native speakerism and its repercussions. The ‘Native Speakerism, Undone’ series was broadcasted live on LinkedIn and YouTube as a shy attempt to raise awareness of the prejudice non-native teachers face, and where both native and non-native speaker teachers alike unanimously confirmed and condoned native speakerism, as they too had witnessed it first-hand in their own cities, throughout their teaching careers.

The local market of available and qualified teachers has no appeal for most language schools as they all seem to claim their customers want native speaker teachers imported from inner circle countries (US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and in some cases Ireland and South Africa). And so, the vicious circle repeats itself with no roadblocks for these misconceptions perpetuating among learners of English worldwide. What makes matters worse is that the stakeholders of the industry are unwilling to admit to having any fault in creating these fallacies. They have turned a deaf ear to the appeals of non-native

English-speaking teachers worldwide and their repeated calls for justice in the ELT industry.

Trafficking ‘native speaker’ teachers with the minimum requirements has become the norm. Within institutions in Italy, it’s easy to overhear chatter about a friend or distant relative of a native speaker, maybe visiting from overseas, who could just be the right fit for a new experience as a ‘teacher of English’. Jobs are handed out to backpackers and tourists who are not even actively looking to be teachers but who will not turn down paid classes that make ends meet, where they can have a friendly conversation and be treated with undeserved authority and respect, they might even start considering the career. Meanwhile, the blame is put on the public system, where local English teachers are metaphorically lynched for shortcomings in language instruction because of their bad accents and for not having experience living abroad – abroad meaning anglophone countries – again assuming all skills are inherently learnt from being born a native speaker or from proximity to native speakers.

When will we take ownership for what is happening? When will we stop trafficking native speaker teachers where clearly there are enough competent teachers, anywhere in the world, in the first place?

Kachru, B. (2005). Whose English is it? Asian Englishes: Beyond the Canon. Hong Kong University Press.

The Non Native Speaker. (2024, January 19). Native Speakerism, undone [Video]. YouTube. www.youtube.com/ watch?v=lW39zloFgKQ

The TEFL Academy: www. theteflacademy.com/eu/online-tefl-course/? gadsource=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwkuqvBhAQE iwA65XxQHCBDNPXYSI3eJplJojD9qXZeA a7yjiGS3hfnY1aHiVWTGWaChnNDhoCmv QQAvD_BwE

thenonnativespeaker.meri@gmail.com

Gillian Flaherty gives advice for materials writers on how to write for markets you have not lived in or visited

It’s fair to say that nothing can replace local experience and knowledge. However, at some point, most ELT authors write for countries they haven’t taught or lived in. My writing experience includes China, Thailand, Japan, South Korea, Pakistan, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America. Over the years, I have taught many students from these countries in private colleges, community programmes and university settings in Australia, but I have not lived and worked in all of these countries. So, there is a potential gap for ELT writers in terms of understanding enough about the target student to create materials that melt seamlessly into the local market.

Writers usually receive a culture brief, but this often doesn’t go beyond a list of dos and don’ts, including the muchdiscussed PARSNIPs (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, ‘isms’, pork). But is this enough input for the writer? And what if they are relatively inexperienced or haven’t written for a particular country before? I have been able to develop a deep knowledge of my target students and teachers over a long period of time, using a range of approaches. I think it is a useful exercise to examine what writers can do to develop their understanding beyond the culture brief, so the aim of this article is to educate ELT writers in how they can build the habits they need to make this a reality.

Find out about the education system

Ministry of Education websites are an extremely useful source of information. The news, media and press release sections are an effective way to find useful information quickly. This is particularly helpful if you want to read a little about the educational setting in general. But these pages are also useful when looking for specific information. For example, you might be able to find out how digital education is used in the classroom, whether there are initiatives to encourage girls to study STEM, or what kinds of interschool competitions exist. Ministry websites will also usually have the academic calendar, which can be useful as writing about the school experience is a popular

Gillian Flaherty has been in ELT for 30 years as a writer and teacher. She has written for a wide range of countries including China, Japan, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America. Gillian holds an MA in Linguistics and an MA in Applied Linguistics and TESOL.

theme. Other interesting and useful topics include school health programmes, global partnership programmes and of course, how the school system is organised. One of my favourite ways to gain insight into the school system is by investigating individual school websites. They are a treasure trove of the nitty gritty information that helps make materials highly relevant and relatable. You can learn about the shape of the school day, special days that are celebrated, and important events like high-stakes exams or sporting events. You can also read about school facilities, which is especially useful when considering what kinds of extra-curricular activities your target students may take part in. The school policies page can be illuminating as well, as it gives you a glimpse into some of the kinds of issues that are prevalent. I also take a look at the staff page when I want to get a handle on the subjects on offer.

Find local publishers or international publishers that have published in the country or region and examine their materials. This is a good way of understanding appropriate pedagogy and topics. Publishers’ websites will have a catalogue of their ELT list, from which you can often find detailed contents pages, spreads from books and even downloadable samples. These are a great resource when getting to know a new market. It’s helpful to see which exercise types are used as this tells you a lot about the likely teaching pedagogy. It’s important to emphasise that I’m not suggesting you stray from your writing brief. But it is useful to know, for example, that open, unstructured speaking activities are common in popular local coursebooks, as it may inform how you tackle speaking activities. Or it may inform the questions you ask if you need to seek clarity of aspects of the brief. Sometimes you can even learn from the covers of local ELT

titles, as they can illuminate what kinds of themes and topics are popular. Local publishers’ websites also provide useful information about the market. You can see how it is segmented, what kinds of skills books are available and, importantly, which exams are common.

Different regions favour different examinations; IELTS, TOEIC, TOEFL, Cambridge Certificates, etc. Having this knowledge can enhance your understanding of the educational landscape, learner motivations and English pathways. Common exam question types are often used in review pages and unit tests. Understanding the origins of these questions helps you create meaningful and effective material. There are many resources available that focus on specific exams, their question types, how to write them and how to answer them.

Many countries have English language news sites which are a great way to learn more about a place. Reading local news will help you increase cultural understanding, learn about recent history, and build awareness of topics and issues of importance. Examining local news and the local take on international news is a fascinating exercise that can blow apart the Global North perspective that many take for granted. If you have already been provided with specific topics for texts, or if you are looking for them, local news sites are a wonderful resource. They often have sections that are more topical, rather than news-oriented. You may be asked to write a text about an interesting technological development from a countryspecific perspective. Local news sites are likely to have feature articles about exactly this topic. Many cover topics such as technology, culture, sport and travel – all potentially useful topics for the ELT writer. Reading these kinds of articles will fast-track your understanding of the target culture, even if you don’t use any of the content directly.

It’s important to be open to the fact that an activity that works well in a mixed L1 classroom in the UK or a summer school in

Spain, might not work in a different context. A willingness to compromise is an essential part of ELT writing. If you can truly engage with feedback as soon as you start to receive it, it will make your job a lot easier. I recommend creating a project-specific checklist based on editorial comments. It will inform your writing and act as a useful self-editing tool, and greatly add to your understanding of ELT in each country. It may also be the basis of a useful resource for other projects.

In my experience, if a question is brewing, it is always a good idea to ask it. A decision you make today in how you interpret an element of the brief, will continue to pop up for the duration of the project. The people who have developed the brief are the experts and you should take advantage of their understanding of the teachers and students you are writing for.

Reframe feedback as collaboration

If you cannot picture yourself in front of the class the materials are for, you will

benefit from all the guidance and input you can get. In some of the countries I’ve written for, I’ve been assigned a monitor, usually a teacher or university professor, to comment on the first draft of the manuscript. Sometimes this happens before the manuscript goes to the editor, sometimes after, and sometimes they collaborate on the feedback. This process is invaluable. It’s a rigorous and thorough business and can feel tough at times, but is so very helpful. It is easy to become disheartened as a writer if you receive a huge amount of feedback that leads to a lot of rewriting. However, it is useful to reframe this as an opportunity to collaborate, and remember that it helps you develop your skills and adds to your understanding of the target audience. That may sound a little trite, but it is a helpful thing to remember throughout your writing career. There is almost always a gap between what the publishing team want, what is in the brief and what is understood by the writer. So, it should be no surprise that some degree of collaboration in the form of editing and rewriting is part of the process.

As a final note, perhaps ELT writers

should consider the development of awareness beyond the culture brief as part of their CPD responsibilities. Sandy Millin has developed an excellent resource, A competency framework for language learning materials writing, and I hope that this article complements some aspects of the framework – namely, Section 1: Background knowledge; Section 2: Creating materials, 2.1 Meeting learners’ needs and 2.2 Activity design. Hopefully, my article provides some effective ways to achieve these competencies and will also inspire ELT writers to come up with their own ideas.

Reference

Millin, S. (2023). A competency framework for language learning materials writing, Version 1.0 https://sandymillin.wordpress. com/2023/12/12/a-competency-frameworkfor-language-learning-materials-writingversion-1-0/

gillian@eltwriting.com

Bruno Sousa looks into taboo issues in the classroom and considers whether or not they should be addressed in the classroom

Introduction

Being a teacher of English for almost fifteen years, I have come across countless concepts taken at face value: from Multiple Intelligences to native-speakerism. A few of these concepts seem to be unchallenged truths that (many) EFL practitioners simply abide by without further analysis. Not only do I believe these should not be unchallenged truths, but I also think some of these concepts may be harmful at the end of the day. In this article, I will go over the concept stating that teachers of EFL should not address taboo issues in the classroom and provide a few reasons why, in my opinion, this ought not to be the case.

What is PARSNIP?

The acronym PARSNIP has been a staple in the EFL industry for a few decades.

Summing up issues that should not be addressed in the classroom, PARSNIP stands for politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, -isms, and pork. These add to topics we should not address in the classroom for different reasons. Insofar as it may seem like a way of being sensitive in the classroom, I do not believe this is the case. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, is it not? We shelter learners from having to tackle issues of relevance to their lives and create an environment of relaxation and comfort where they can forget all that is going on with their lives and society that surrounds them. But what type of change do we foster by doing so?

Teaching learners to talk about exotic places to travel is the norm, but how useful is that to their lives? Coming from a country in the Global South, using most of a lesson’s time to talk about the lyrics from a certain foreign band or technology can become numbing to our learners. Why are they learning a foreign language? Why are we, teachers, teaching that foreign language?

Language learning is ‘locally situated, personal, socio-historical, and political’ (Jeyaraj & Harland, 2016, p. 589). Many EFL teachers, institutions and materials appear to forget the ‘locally situated’ aspect of language learning. There has been plenty of research on evasion of language courses and why a great percentage of language learners fail to reach advanced levels. All issues seem to be tackled in these surveys, except how learners can integrate English into their real lives, and not only watching yet another episode of a given sitcom or relocating to a new country. In the past few years, we have faced issues such as a global pandemic, racial

Issue 290 2022

2022 2019rights movements, identity politics, misinformation and innumerable others. Yet, it seems that using emphatic language to talk about architecture is the goal when teaching a foreign language. The status quo and colonialism are likely to thrive from these ideals (Grilli, 2020). Why is talking about last week’s political scandal a no-go zone when this is exactly what may be of relevance to our students? Why do we keep saying that education can change the world if we do not foster this change?

The so-called neutrality used to teach English nowadays has shown to be another manner of keeping the status quo and colonialism safe and sound (Pennycook, 2007). Teachers from countries which play a subordinate role in the world’s economy and politics seem to have accepted such a fact. Thus, reflecting upon the use of taboo issues in the classroom should be a common practice for all teachers.

‘Language that is meaningful to the learners supports the learning process. Learning activities are consequently selected according to how well they engage the learner in meaningful and authentic language use’ (Richards & Rodgers, 1986, p. 161).

Even if we should forget political issues related to the use of taboo topics in the classroom, the truth is that some of these issues are the ones which really appeal to learners and, because of that, they will be, inevitably, more cognitively engaged in our lessons.

It is often said that when we do tackle taboo issues in the classroom, this may lead to conflict. In my opinion, this should be both true and welcomed in the classroom. Our job as teachers is to help learners cope with different contexts from their real lives. If learners do engage in conflict, we must be ready to teach – and practice – the use of intonation, the choice of vocabulary, and even self-regulation. This is what we (are supposed to) do, and not simply make English lessons a detached entity from the world where learners talk only about what is pleasant. This is not the real world. Throwing yet another pair/trio task at students does not make it a lifelike task, does it? Content, not only linguistic, also makes up what student-centredness really is. There has been an over-reliance on the communicative aspect of language to the detriment of what learners may really want to express, not only communicate. Talking about your favourite albums with advanced vocabulary, using the right intonation in

certain transactions, or even writing an opinion essay for the university are likely to be far from the only goals our learners really have.

It could be said that skills are transferable, and learners will be able to decide if and when to use language when handling controversial topics. However, as a reflection from the real world, our lessons must provide learners with the opportunity to reflect on their use and power of language and how important it is to use language as a tool of social change.

Even though it may seem like I believe anything goes in the classroom, nothing could be further from the truth. There are issues that should not be addressed in the classroom, but these should not come from prescribed guidelines. How can we know what to address in our lessons? Knowing our learners is key. As with everything, we must know our students well enough in order to understand whether a certain issue can or cannot be dealt with in the classroom. Better yet, understand how we should go about a certain issue in the classroom.

Our usual needs analysis questionnaires, on the other hand, are not close to enough. Of course, these are needed and should be used from the get-go. Other than that, observation and getting to know our learners to comprehend where they are coming from (both literally and metaphorically) is an ongoing job. I do understand we will never be able to know all there is to know about our learners. Yet, I do also understand that we can do a good job knowing them well enough not to bring up issues that may trigger or even cause them some trauma during our lessons. Moreover, we must deepen our understanding of the context in which we (teachers and learners) are set: social, personal, geographical and economic. This is part of the job that seems to be forgotten by a few of us.

If a lesson or material deals with the use of emphatic language to discuss architecture, why can’t we also handle homelessness, rent prices, gentrification and property speculation? Is it because there is a general belief that teachers shouldn’t mention these issues? I do refuse to accept this as an educator. A sentence such as Not only have rent prices skyrocketed, but new flats have been shrinking in size! is way more likely than Not only are gothic churches beautiful, but they are also so detailed! in real life (provided that you are not an architect or architecture connoisseur).

As a Brazilian educator, I have obviously been highly influenced by the teachings from Paulo Freire. One can understand,

then, how hard it is for me to simply ignore what goes on around me because it might be, for some, controversial. Neutrality (as in not addressing controversial issues, but not related to giving our personal opinions) in the classroom is another tool of keeping things as they are since it contributes to the maintenance of injustice (Freire, 1996).

It may be argued that teachers of a foreign language have little power over education as a whole. I surely do not think this is the case. Language is not only a powerful tool, but probably the most powerful of all. From the Bible to speeches and declarations of war, language permeates everything that happens around the world. Knowing a language of prestige (in this case, the language of prestige, English) is probably one of the greatest opportunities our learners have in order to change the world somehow. We must strike a balance between teaching the language, its skills and systems, and finding the relevance to our students’ lives. However, the relevance cannot be limited only to trips, favourite movies, or exotic features of a distant culture.

This is a difficult task. Tackling controversial and even polemical issues may bring a sentiment of unease over learners and teachers. We have been raised and even trained to feel this way. On the other hand, our role as educators should go beyond helping our learners reach different CEFR bands or knowing how to communicate in ways that will not foster social and personal development. If we want our learners to achieve these, we cannot just turn a blind eye to issues of relevance, can we?

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogia da autonomia Paz e Terra.

Grilli, M. (2020). Por uma educação linguística Translíngue e Decolonial: questões para o ensino de alemão. Revista Iniciação e Formação Docente, 7(4). seer. uftm.edu.br/revistaeletronica/index.php/ revistagepadle/article/view/5200

Jeyaraj, J. J. & Harland, T. (2016). Teaching with critical pedagogy in ELT: the problems of indoctrination and risk. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 24(4), 587–598. doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016 .1196722

Pennycook, A. (2007). The myth of English as an international language. In S. Makoni & A. Pennycook (Eds.), Disinventing and reconstituting languages (pp. 90–115). Multilingual Matters. Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. (1986). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2nd ed.). CUP.

bgsousa87@hotmail.com

Jaber Kamali and Montaser Jassouma present their research on the concept of the classroom as an ecosystem, applying a framework as a way to increase learning opportunities through group conferencing

Introduction

Ecology is originally the study of the environment or specific ecosystems and it has long been investigated in social sciences such as language education. Earlier, the introduction of ecology into education was marked by Bronfenbrenner (1979), as he conceptualised a classroom as an ecosystem with distinct layers. Bronfenbrenner (1979) argued that within the context, there exists a series of ecosystems, each nested within the next. According to his model, these can be categorised into different hierarchical layers. In this study, we adapted a three-layered ecological framework, namely microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem, to discuss the considerations for group conferencing as a way to increase learning opportunities for language learners in our language school, Ibn Haldun University School of Languages, Istanbul, Turkey.

One of the aspects of education in which ecology can play a role is group conferencing. The term ‘group conferencing’ has received various interpretations in academic literature. Originating from criminology, Family Group Conferencing applies to situations where the community directly impacted by a crime – including the victim, offender, family, friends and key supporters of both parties – collaboratively determine the resolution of a criminal incident. In an educational context, there are also different definitions that involve a more straightforward scenario, such as an instructor meeting with two or more students to offer feedback and engage in discussions about a writing project draft. However, we extended the concept into a type of ritual for our school on Monday mornings, in which our learners attend a 30 to 50-minute session to learn some study skills and share their experiences and challenges about language learning.

Jaber Kamali, PhD, is a lecturer at Ibn Haldun University in Istanbul, Turkey. He is serving as an Ibn Haldun University Teacher Training Centre Coordinator where he leads and manages different second language teacher training courses including the Trinity CertTESOL and DipTESOL.

Montaser Jassouma is an experienced ESL/EAP instructor and teacher trainer with over 12 years of expertise. Holding an MA in TESOL, a DELTA Diploma, and certifications in education and training, he specialises in learner-centred, techintegrated teaching. Currently, he is a lecturer at Qatar University.

The idea of group conferencing emerged after observing our students for a few years as teachers, before we got into managerial positions, and we realised that those students:

❚ mostly came from the eastern part or less improved areas of Turkey, where online learning resources/tools were limited;

❚ were programmed to nail certain national exams that may have conflicted with what we teach and test;

❚ were not equipped with the right study habits and time management skills;

❚ needed support outside of learning, e.g. emotional support and guidance; and

❚ were usually afraid/not open to communication with management in general. Such sessions bring us together and soften this type of relationship.

Such things may or may not be covered directly by the teacher in class due to many variables; therefore, we came up with this idea to maximise their learning journey at our school.

The topics of these sessions came from various sources. The first source was our observation and monitoring of the students during the semesters. The second was the teachers’ opinions gathered from sources such as the end-of-the-term questionnaire, one-to-one conferencing, and informal chats. The third source was

students’ opinions from questionnaires and interviews. Some of the topics we ran were ‘loneliness in academia’, ‘time management and prioritising’, ‘public speaking and presentation skills’, ‘how to improve speaking skills with some strategies and apps’, and ‘how to build vocabulary’.

After a year of running such events, there were some learned lessons that we thought might help other teachers, Directors of Studies or managers to run these sessions. We will discuss them in relation to the three levels of educational ecology in turn.

The microsystem in educational ecology refers to the immediate and direct interactions within a specific environment, such as a classroom, school, or self, where students and teachers engage in daily interactions. What we learn in this layer of educational ecology is that students prefer topics that have a clear connection with their immediate life and needs. For example, from the topics presented, public speaking, speaking skills strategies and apps, and time management skills, which have a close connection with students’ academic life, were the most popular sessions. Therefore, we concluded that choosing topics should take a bottom-up approach, i.e. asking students to suggest topics, and then prioritising these based on the elicited and perceived needs of the students.

We also discovered that different types of student knowledge should be taken into consideration. For example, lowerlevel students need more linguistic help, so translanguaging can be a practical solution here. This can be done by providing subtitles for multimedia used in the session or in some instances using L1.

The mesosystem involves the connections and relationships between various microsystems, highlighting the interplay between different settings within the educational system, like the collaboration between peers, teachers, etc. to support a student’s learning experience. In this layer, institutional considerations are discussed. Raising teachers’ awareness of the importance of these sessions

Issue 290 2022 2022

2019 seems to be necessary to encourage them to take a more active part in these events, and help students benefit from their experience and expertise in language learning. For example, one of the participating teachers stated:

… Teachers should be aware that their contribution may have a great impact on students’ academic/nonacademic lives. Unfortunately, some teachers perceive this as a burden; they are unaware that doing such things (reflecting on their journey when they were learners, sharing their experiences and personal encounters) will make their job more meaningful and rewarding.

The teachers’ participation becomes more important knowing that they are mostly non-native teachers who have themselves experienced language learning and are familiar with its ups and downs. The support students can get from their teachers in these events is immense and it can act as an extracurricular benefit.

The macrosystem encompasses the broader cultural, societal and institutional influences that shape the overall

educational environment. These include policies, ideologies and social norms that impact education on a larger scale. The biggest advantage of group conferencing on learning lies in the sociocultural aspect, which brings all the students into a community in which they can freely ask questions and find people with common goals and difficulties, helping them to feel more comfortable. These sessions provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment, placing an emphasis on creating a safe space for individuals to share their challenges. Group conferencing encourages peer connections, allowing students to share experiences, learn from one another and build a sense of community. The sessions promote empathy and understanding, reflecting Rogers’ belief in the importance of these qualities for personal growth. The role of the facilitator in guiding discussions and providing support mirrors the facilitator’s role in Rogers’ group therapy. Overall, these sessions contribute to academic development and holistic growth, fostering a community where students can collectively thrive academically and personally.

In summary, our exploration of the educational ecology of group conferencing at our school revealed valuable lessons across three layers: microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem. Notably, we emphasise students’ involvement in selecting relevant topics, considering diverse knowledge levels, securing institutional support, and recognising the sociocultural benefits of communitybuilding. These insights highlight the importance of such sessions in the educational curriculum of language schools to build a sense of community in them.

Reference

Bronfenbrenner‚ U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

jaber.kamali@ihu.edu.tr

Introduction

Among the numerous approaches and methods in second and foreign language teaching, only a number stand out as able to meet the modern learner’s needs. Looking critically at an overview of instructional methods for more effective language classrooms with a focus on productive and receptive skills, learners need teaching based on research-based strategies while the instructor observes differentiated instruction and assessment to meet the needs of diverse learners. The aim of this article is to focus on the most effective language teaching method in the context of English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching, based on the typical language classroom situation seen in Kazakhstan and the challenges therein, consequently, proposing communicative language teaching (CLT) as the trendsetting approach to meet these challenges.

The Kazakhstani context

Kazakhstan is blessed with a multilingual environment which is championed by Russian language. This suggests that in a typical English language learning classroom there would be a diversity of learners. Furthermore, English being introduced through the trilingual policy in 2010 opened a new door for EFL. One could argue that it was practical to have English as part of the language policy along with Kazakh and Russian because it is the medium of instruction in many universities across the globe, coupled with the fact that most academic resources and research papers are in English.

Generally, an EFL environment is one in which the learning situation comprises learners learning English for the purpose of using it with other English speakers in the real world. The Kazakhstani scenario presents a unique scenario because building language teaching classrooms for its English learners, a foreign yet practical approach was needed, which was the adoption of the grammar translation method – ‘a method of foreign or second language teaching . . . makes use of translation and grammar study as the main teaching and learning activities’ (Richards & Schmidt, 2002, p. 231). The Kazakhstani English teaching classrooms used this method because it worked. But

Mark Nwaefido is an experienced and well-qualified English Language and Literature Teacher at the International School of Almaty, Kazakhstan. He has an MA in TESOL from Eton University, Delaware, USA; a Professional Certificate in Leadership and Management in Education from the University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia; a Doctorate in Education and a Diploma in TESL from the Canadian College of Educators. He also works with Webster University as an Adjunct Assistant Professor.