A warm welcome to the November/December issue of IATEFL Voices, the last one of the year and the first one to be completely digital. Following on from our milestone sustainability issue in September/ October, as part of IATEFL’s commitment to more sustainable business practices, IATEFL Voices will be completely digital for both individual and institutional members from now on. This is an excellent opportunity for Voices, and one which sees the introduction of two new columns: Green IATEFL and From the British Council.

Christopher Graham reflects on his first few months as IATEFL Vice President in the From the Trustees column, recounting the challenges and steep learning curve of a new VP but also giving thought to the coming months. Chris has also written the first Green IATEFL article, following on from its introduction in the last issue of Voices. Here, he continues the theme of sustainability, asking various IATEFL members and Trustees what sustainability means for them.

We then move on to the second of our new columns, From the British Council, which for this issue has been provided by Alison Devine, the British Council’s Head of English Connects. Alison summarises some of the professional development opportunities available for teachers and teacher educators and is well worth exploring.

In the first of our feature articles, Peter Westerhuis and Sena Elibal-İçuz explore the use of artificial intelligence in academic writing, considering how AI can best be deployed to appropriately support teachers and students of academic English.

In two related features, Roslyn Young and Laurence Howells present and discuss the Silent Way tradition. Roslyn provides an overview of her work in helping people learn and teach languages. Laurence presents an interview he conducted recently with Roslyn where they discuss a class conversation, what it is and how it can be successfully implemented in the classroom.

Laura Hadwin looks at informal feedback in her feature article, considering how such feedback can be effectively designed and implemented to provide a positive teaching and learning experience.

Vanessa Rodrigues Bocchi Barbosa picks up on classroom positivity through her discussion of classroom management, providing various examples that promote Positive Discipline. Romina Sabia returns to Voices to look at artificial intelligence, her journey using AI tools as well as how AI can promote personalised learning.

Both Seda Yaman and Ahisha Haneef explore learner empowerment, Ahisha through the use of a project-based approach and Seda through considering strategies that can help build learner confidence. Empowerment is the theme discussed by several SIGs in the From the SIGs section, with BESIG, LTSIG and ESOLSIG outlining what empowerment means to them and how they engender it throughout their SIG events and activities.

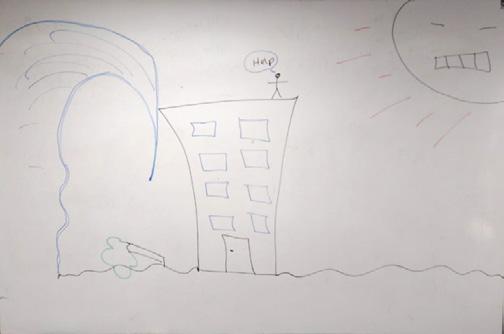

There are two lesson plans for you to sink your teeth into in the For the Classroom section. In the first one, Mohamed Ramadan provides a lesson about productivity and in the second, Ignacio González presents one on natural disasters in the context of global warming.

Finally, Associates Representative Jean Theuma outlines strategies that teacher associations can adopt to effectively and efficiently promote their events.

With the Annual Conference only around four months away now, November sees the announcement of all the speaker proposals. If you have submitted a proposal, very best of luck. And I hope you all have a lovely and relaxing time over the coming holiday season. See you in the New Year!

With best wishes

Derek Philip-Xu Editor, IATEFL Voices

At the IATEFL Conference in April, Christopher Graham was elected as the Association’s Vice President. Here, he talks about his first few months as VP as well as what is in store over the coming months of his tenure.

I’m writing this in the middle of August in sweltering heat in France. Very different weather from the great British rain in Brighton almost exactly four months ago to the day, when I became Vice President. This is to reflect a little bit on what has happened in the last four months and also to describe some of the things that I hope will happen over my tenure as Vice President, and from the Edinburgh Conference next year, President. These last four months have been a very steep learning curve for me. IATEFL is a complex organisation and there are lots of things that go on behind the scenes that regular members don’t know about – they don’t need to, but I do. I’m grateful for the immense patience from colleagues in Head Office, other Trustees and Committee Members in helping me navigate it, all in my fumbling way.

But what have I discovered? I’ve discovered that you can get things done. Assuming that thing is not a completely ridiculous idea, there is a great deal of support for new initiatives from Head Office, other volunteers and from members. In my case, this has been around the creation of Green IATEFL. Those of you who know me are aware that I’ve been working on the intersection between ELT and environmental sustainability for about four years or so now, and I’m delighted that working with colleagues at IATEFL we are shaping what I think will be a really interesting approach to this. IATEFL has for a while now been working on its own green policies, and Green IATEFL will work to develop and nurture sustainability across the ELT community, with all stakeholders whether they be members or non-members. IATEFL Voices 300 was the sustainability issue, and you will have heard plenty in there about green issues.

But believe me, there’s a lot more to come and you’ll be hearing from me, both directly and through the SIGs and Associates, encouraging you to get involved.

In my day job, I work with teachers in challenging contexts, in conflict and post-conflict settings, and have immense admiration for the way people manage to work in such traumatic circumstances. I hope in my time at IATEFL, we are able to increase our offering for teachers, not just in conflict zones, but also in areas of very low resources and other challenging circumstances. We do of course already work in these contexts in various ways, but I hope we can always keep these teaching settings in our minds as we plan events. To keep me grounded, I have a recollection of a very committed young Iraqi teacher with tears in his eyes talking about his challenges. If you grab me at conference, I’ll tell you his story.

I’m a very committed non-geek, but even I am aware that artificial intelligence (AI) is providing us with great opportunities to do some really exciting things within and beyond our classrooms. But my green antennae have started to ping. Hearing Vicky Saumell’s talk at Brighton in the summer has made them ping even more. So, I’m delighted that IATEFL is engaging with AI, and that we are all talking about it. It’s right that we should, but I hope we

manage to view it through the lenses of sustainability, academic rigour and intellectual property rights as well as its benefits.

Becoming VP was a thrilling moment for me. But it’s becoming a Trustee that has really made me focus. The clue is in the name – trust. Being part of maintaining the integrity of the Association is something that, in common with the other Trustees, I take very seriously. I think I said in my election campaign that it’s important for us to remember that IATEFL doesn’t have any money. It’s your money, and it’s money from sponsors, exhibitors and donors. It’s my money too, thinking about it. Joint responsibility for that money is something I feel very privileged to have been granted.

My final thought is that in my campaign to become VP, one of my undertakings was that if I won, I would be accessible. And that is something I remain committed to. So please never hesitate to get in touch with me. No question is too trivial. And if I don’t know the answer, I’ll let you know, and I’ll ask someone who will know. Equally, if it’s not something that we can do, I won’t hesitate to tell you and explain why. IATEFL is governed by UK charity law, and we have to follow this to the letter.

chris@iatefl.org

Copyright Notice

The International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language was founded in 1967.

Registered as a Charity: 1090853 Registered as a Company in England: 2531041

Disclaimer

Views expressed in the articles in Voices are not necessarily those of the Editor, of IATEFL or its staff or trustees.

Copyright for whole issue IATEFL 2024. IATEFL retains the right to reproduce part or all of this publication in other publications, including retail and online editions as well as on our websites.

Contributions to this publication remain the intellectual property of the authors. Any requests to reproduce a particular article should be sent to the relevant contributor and not IATEFL.

Articles which have first appeared in IATEFL publications must acknowledge the IATEFL publication as the original source of the article if reprinted elsewhere.

all talk

but what is it exactly?

Following on from his articles in IATEFL Voices 300, the sustainability issue, Christopher Graham returns to the recently launched Green IATEFL initiative. In what will be a regular feature for Voices, he navigates the question of what sustainability actually is.

As part of the Green IATEFL initiative, the purpose of this article is to consider the tricky question of what sustainability is and might mean for us.

I’m an ELT person and it’s difficult for me to write something without some kind of activity in it. Sorry. There are three questions below for you to answer before you read any further. You could do this alone, or with colleagues.

I asked the same questions of a number of people within IATEFL including Head Office staff, Trustees, Brighton plenary speakers and from the IATEFL Live team. Hopefully, this will get us all thinking.

1 How would you define sustainability in general and in ELT?

2 What can IATEFL and the wider ELT community do to play its role in fighting the climate crisis?

3 What are the main barriers we face in this?

Here are extracts from the answers from our colleagues, and a few comments from me.

How would you define sustainability in general and in ELT?

Jon Burton (Chief Executive, IATEFL)

It depends on if you are referring to sustainability in terms of the environment, or in terms of things like its ongoing viability and the threat to it from technology – particularly artificial intelligence (AI).

This is interesting because Jon tackles the issue head-on by separating environmental sustainability and the

broader viability of ELT. The two, of course, are interconnected because as we find ourselves increasingly having to meet environmental challenges head-on, this may impact the viability of some of the things that we do in ELT at present.

Andy Hockley (Trustee, Special Interest Group Representative)

Sustainability to me is making sure that you think about how something will be maintained and continued over time. In ELT, to give an example, creating a selfaccess centre for students at your school is only likely to be a successful project if you have thought through the costs and staffing that you will need in order to maintain it and keep it open. In the sense of sustainability as it refers to climate change, there are two strands in ELT: a the business of schools committing to act in an as environmentally responsible way that they can, for example in a carbon neutral way; and b the use of the ‘theme’ of global warming and all that this encompasses, in the lessons themselves.

So, Andy offers an excellent example of a sustainable project for an institution, and he also goes on to make that key distinction between the negative environmental impact of what we do as a community and the role we have in climate change education.

Vicky Saumell (Conference plenary speaker)

For example, using materials for longer cycles, switching to digital whenever possible.

Definitely something everyone involved in materials production needs to think about, and something that would impact the business models of some stakeholders.

What can IATEFL and the wider ELT community do to play its role in fighting the climate crisis?

Sarah Ward (IATEFL Head Office Sustainability Champion)

It is important for the climate crisis to be on the agenda, encouraging discussions and awareness where possible. And it should be done in a way that allows individuals to feel empowered to make small changes to their own practices, doing what they can with what they have in their own contexts.

The importance of context – one size does not fit all. Sarah continues:

The biggest areas of concern are the Annual Conference, and the face-to-face events organised by the SIGs. Both of

these come with a lot of inevitable air travel. We encourage delegates to use other public transport where possible, to make the most of their time in the UK to avoid multiple flights per year. We have also almost eliminated other air travel for face-to-face meetings, encouraging more committees to either meet online or during the Conference, when they would be travelling anyway.

The importance of recognising our biggest negative impacts and engaging with them, rather than hiding them ‘under the carpet’. IATEFL is aiming to become a force for good in this area.

Jon Burton

Jon suggests we can:

Share best practice with other teacher associations and event organisers, and learn from other bodies. Promote best practice amongst other relevant stakeholders: teachers, institutions, publishers, online service providers, etc.

Maria Araxi Sachpazian (Trustee, IATEFL Secretary)

Train teachers to do things differently. It’s easy to tell people to go paperless but this seems scary. We need to provide training and make sure that these solutions are applicable in all teaching environments. Institutions and other employers have a responsibility to build sustainability into their CPD programmes.

Gerhard Erasmus (Trustee, Membership Committee Chair)

We have to move beyond lesson plans and catchy ideas. We need to start asking questions like: Are we actually environmental sustainability compliant in terms not only of paper use, but recycling, renewable energy and within our communities? Are our suppliers compliant? Again, the institutional responsibility aspect.

What are the main barriers we face in this?

Sarah Ward

For IATEFL Head Office, one of the major barriers we face is financial. Often the least sustainable option is the most cost-effective one and we have to strike a careful balance between the two.

This is one of the most complex aspects of becoming sustainable. In the short term it can cost more money.

Jon Burton

Jon reinforces this and adds the angle of eco-anxiety:

Fear and a sense of hopelessness. Not all sustainability actions are financially viable.

Gerhard Erasmus

It will take something drastic, and people are unwilling to make drastic changes until it is too late, says the doomsday prophet. Depressingly, I have to agree with him. But we must keep on pushing.

Jean Theuma (Trustee, Associate Representative)

IATEFL values equality, fairness and has made it clear that it has a neutral stance of issues of a political nature; yet many areas of sustainability overlap into politics. Due to the economic, environmental and social dimensions of sustainability, it may be difficult to separate sustainability from political, religious and cultural approaches. This is a reminder that sustainability is politically charged and has economic

impacts, and that this has consequences for teachers, publishers, authors and other stakeholders. Difficult conversations have happened and will continue to do so.

Anca de Vries (IATEFL Live!)

To actually empower teachers to make changes, we need inspirational leaders to make people look past traditional rules and regulations and to change the way things are done.

And that, dear reader, is a role some of you need to take on in your institution, teacher association or wider community.

Vicky Saumell

And the change of mindset necessary to bring about these changes, in contrast with the ‘how things have always been done’ rhetoric is also an issue.

Alison Devine is the British Council’s Head of English Connects. Here, she summarises some of the professional development opportunities available for teachers and teacher educators

Are you aware of TeachingEnglish – the British Council’s global online community for English teachers and teacher educators with inclusive, up-todate resources and discussion spaces to facilitate collaboration and exchange of ideas? Whether you wish to build your professional network, share tips and knowhow, or learn about the latest research and innovations in teaching, our accessible, open TeachingEnglish platforms provide classroom resources and professional development opportunities, including lesson plans, events, courses and publications.

What’s on TeachingEnglish in November?

Every two months, the content on TeachingEnglish focuses on a different professional practice from the British Council’s framework for professional development. In November, we are

focusing on Knowing the subject. We are also highlighting climate in connection with CoP29.

Our 13 November four-hour webinar event for teachers, ‘Teaching the four skills’, will explore interactive teaching strategies and tools for writing and how to teach speaking skills, with our monthly panel discussing tried and tested ideas for teaching the four skills in the classroom. The event will be available on Zoom and livestreamed into our TeachingEnglish Facebook community

Teachers looking for self-access training can check out our Understanding language systems course, which runs until 30 November 2024. This course helps develop understanding of functional language and grammar and how to apply this knowledge to teaching through reflection, analysis and effective presentation of use and form. Or, if you’re more interested in improving your skills in integrating pronunciation, there’s the How to teach pronunciation course Whatever the course, our Facebook community, Courses for teachers, offers a space to exchange teaching tips, additional resources and reflections on course content.

Teacher educators can learn more about how to support teachers in their professional development by taking our Helping teachers to learn course, which reviews how to plan and deliver effective training, set up and support communities of practice to facilitate collaboration, and learn how to encourage all types of

Conclusion

Hopefully, these questions have given you some food for thought. Back to the original activity, how did your responses differ from those here? Can these questions be a catalyst for further action? Please feel free to get in touch.

‘The most dangerous phrase in the English language is: We’ve always done it this way.’ – Grace Hopper, US Navy Rear Admiral and renowned computer programmer

chris@iatefl.org

self-directed learning. Visit our teacher educator landing page for details of all the resources available and our webinar page for themes, dates and registration for the monthly teacher educator webinar programme.

Through our TeachingEnglish Facebook community, we will also livestream sessions from this year’s ELTons Festival of Innovation on 19 November 2024, where industry experts tackle thought-provoking questions and present genuinely innovative solutions to the real challenges faced by teachers and learners today. While over in our Instagram community, we will be joined by @TeachersofEnglish in Argentina to talk about teacher reactions to this month’s resource shares and what they are saying about Knowing the subject

January?

December and January focus on the professional practice of Taking responsibility for professional development, which helps teachers understand their own professional needs, interests and learning. In our new course, Making time for research in the English language classroom, you can discover how to reflect on and explore issues in your teaching context, plan and carry out a small-scale classroom research project and communicate your findings effectively. Our TeachingEnglish communities on Facebook and Instagram will ask

Issue 290 2022 2022

2019 members to tell us their preferred ways of learning about teaching and what we can all do beyond training. We will shape some of our discussions around our CPD framework, recent webinars on this topic and highlight new publications such as Improving teacher development through the effective use of social media groups, which looks at how we can all use social media to develop our knowledge and skills. Our four-hour webinar event for teachers, ‘Helping our learners develop’, is on 11 December. It will cover integrating social and emotional learning into classroom management, building rapport

and managing stress with teens, and practical classroom ideas that use empathy and emotional intelligence to promote wellbeing.

In response to interest in the topic of artificial intelligence, we have created four new lesson plans for secondary/adult learners on AI literacy: My AI teacher, What is AI?, The risks and benefits of AI and AI and ethics in education. The lessons cover CEFR levels A2–C1. All lesson plans are designed to help learners use AI effectively, safely, critically and ethically –both for learning and for life.

The TeachingEnglish podcast also

focuses on key questions being asked by English teachers all over the world. Each episode features expert guests and explores a current issue in the world of English language teaching; from artificial intelligence to using the creative arts, from critical thinking to how to teach vocabulary and grammar more communicatively. Show notes and transcripts in English and Arabic are available to download for each episode. Series three is out now!

TeachingEnglish@britishcouncil.org

Peter Westerhuis and Sena Elibal-İçuz explore how artificial intelligence can be put to good use for academic writing, helping both teachers and students

Sena Elibal-İçuz is a Senior ELT Coordinator at ETS Global and is based in Istanbul. She has degrees in English Literature and credentials in ELT, with over 7 years’ of teaching experience at the university level, including academic and administrative duties.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping many areas of our world today, and education stands out as an area where its revolutionary power is particularly evident. With all its diverse capabilities, AI significantly influences how we learn, teach and interact with information. Even while writing this article, the built-in AI in the word processor is suggesting ways of improving our writing, some of which we more than happily accept and apply. As educators, we find ourselves both increasingly fascinated and concerned by the capabilities of AI. Teachers ask, will it be an obstacle to our teaching or impede the students’ learning? The question of academic integrity also worries many people. Is it possible to find a way to harness AI in the classroom before it outwits us?

Peter Westerhuis is a Senior ELT Coordinator at ETS. With over 12 years’ of teaching experience, he has taught English at various levels from primary school to university in Canada, South Korea and France.

Even if definitive answers to these questions have yet to be found, we have the capacity already to harness AI to our advantage. In judiciously leveraging its many capabilities, we can use it to enhance teaching and learning rather than perceiving it as a threat to academic integrity. While informed AI use can potentially benefit various aspects of teaching and learning English, one specific area of interest is its use in academic writing.

Educators face a range of challenges when guiding students through academic English writing. Such challenges include bridging the gap between general and academic English, addressing language barriers and cultural differences. Additionally, they must help students become more familiar with English writing standards. It has been shown that linguistic obstacles and time constraints further complicate the teaching process (Ghafar, 2023). Recently, instructional technologies and AI have emerged as potential gamechangers in the way academic writing is taught and learned. Let’s look at how AI can address these challenges and enhance the process and the quality of academic writing instruction.

The first thing that AI tools, such as ChatGPT, can assist with is creating academic writing curriculum by designing a semester-long programme with weekly themes, learning goals and recommended activities. These tools can also generate model lesson plans for specific classes or even individualised materials for students. Use them to create engaging activities, dialogues and other tasks tailored to the students’ needs. Then use AI tools to generate specialised vocabulary lists, case studies and role-play situations. Generating example reports can also

be a resource to help students understand the teacher’s expectations. Furthermore, the tools can then create assessments to measure student progress and comprehension of the material.

One remarkable aspect of AI support for educators lies in its capacity to tailor an existing curriculum to address the distinct requirements of diverse student groups. By providing guidance on effective pedagogical methods, fostering interactivity and suggesting engagement strategies, AI can help classroom materials remain both captivating and impactful.

When it comes to evaluations, AI can help set up feedback systems for gathering student writing responses. These responses can also be used to help refine curricula. AI streamlines the grading of written assignments and can also identify writing patterns and trends in a classroom. It can assist with teacher administrative tasks, generate rubrics, manage data for class reports, write reports and summarise documents.

To maximise the benefits of AI tools, educators should continuously improve the prompts they use. AI models learn from the data they are exposed to, and by refining and iterating on the prompts, you can achieve more accurate and relevant output. Here are some tips from ETS AI Labs for guidance in this process: Be laser-focused Craft clear and specific prompts to ensure that the AI tool understands the desired output. For instance, instead of asking it to ‘Write an essay on the environment’, ask it to ‘Write a 500-word explanatory essay on the effects of climate change on marine biodiversity, highlighting three specific species and their changing habitats, with three main points and a conclusion’. This way you receive a structured essay that you can review and adapt to use as an example with your students.

Question it right

Formulate relevant and engaging questions to elicit creative and informative answers. Rather than asking, ‘Can you help me with grammar lesson planning?’, specify your needs by asking, ‘What strategies can first-year university students use to improve their grammar skills in academic writing?’ This approach ensures that the AI tool provides more targeted and useful responses.

Optimise with context

Provide background information to help AI tools generate more accurate responses. Specify the essay’s purpose, audience and scope, and include any relevant research or sources that have already

been consulted. This additional context ensures that the AI tool can tailor its output to meet your specific needs. Engage, don’t dictate Use AI tools as collaborative partners to generate new ideas and insights, rather than simply issuing commands. Start your writing prompts with openended questions such as ‘What are some common mistakes in academic writing at the university level, and how can students avoid them?’ Then, refine your needs with follow-up questions (ETS, 2023). This method ensures a more interactive and productive dialogue with the AI tool, leading to richer and more nuanced responses.

With the abundance of online resources available to help teachers use AI tools responsibly in the classroom, it can be overwhelming to know where to begin. AI 101 for Teachers stands out as a particularly valuable resource, offering online learning sessions with experts, along with practical guides and companion resources. One particularly insightful session explores how AI can be integrated with pedagogy to enhance student learning. The series also covers topics ranging from demystifying AI to promoting a responsible approach to its use in education. It also provides insights into teaching with AI tools and leveraging AI for assessment Practically speaking, educators may also start by using the pre-made prompts they provide and then adapt them to their needs. By following these guidelines and examples, teachers can improve their teaching of academic writing, benefiting both themselves and their students (Code, 2023).

If you would like to learn more about different AI tools and how to incorporate them into your preparation and teaching, you can watch the recording of the Virtual Seminar for English Language Teachers: Humanizing AI for Learning and Assessment. Participants share ideas, present different AI tools and discuss best practices for maintaining a human touch while incorporating AI into the classroom. If you specifically want to explore using AI for academic writing purposes, register for the ETS teacher webinar series which includes a session about using AI tools in academic writing, with examples from the TOEFL iBT test.

Potential plagiarism and disruption of learning due to excessive dependence on AI tools are getting teachers and institutions concerned about AI use for learning purposes. Imposing a ban on AI use, however, might not be the ideal solution since developing AI literacy and competencies will most likely be important skills in the future.

A more balanced and guided approach to AI use can be instrumental in addressing concerns associated with overreliance and misuse issues. Instead of an outright ban, teachers and institutions can provide guidance on the responsible and ethical use of AI tools and raise awareness of its limitations and potential dangers. As a first step, certain restrictions and guidelines on how to use AI and for what purposes can be included in the syllabus or code of conduct (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023).

To ensure AI use does not disrupt learning or undermine human agency, AI-assisted activities can first be modelled in the classroom and combined with critical thinking. Here are some ideas for involving AI in your academic writing classes to encourage your students to use it appropriately.

Ask your students to come up with ideas about a writing topic and then prompt AI to do the same. You can then ask your students to compare and contrast their own ideas with the AI-generated ones. They can improve their original ideas with the AI output, or you can encourage them to think critically about the AI-generated ideas. Since AI has its own limitations generating output, it can be scrutinised critically and improved.

Summary

Students can use AI for reading into writing activities, such as summary writing or summary and response writing. They can compare their own summaries with the AI-generated ones and check their own summaries for redundancy, missing information or possible improvements.

Checking register

Your students can get AI to check their writing for appropriate tone and delivery and get feedback to improve. They can practise delivering the same information to different audiences or in different styles, using targeted vocabulary.

Test preparation involving academic writing

AI can also help with test preparation by providing sample task prompts based on examples it is fed with. By providing AI with scoring guides, you can also get feedback on written responses. A good example can be the TOEFL iBT test, which is a major English proficiency test that includes the assessment of academic writing along with

Issue 290 2022

2019other language skills. The Integrated writing task in the TOEFL iBT test requires reading a short passage and listening to a short lecture on the same topic, and then summarising the points mentioned in the two sources and explaining how they relate to one another. As a suitable AI tool that can provide feedback on written input, students can feed ChatGPT with the reading passage and the lecture script along with the scoring guide for this task, which is publicly available, and get it to score their written responses. ChatGPT can also be prompted to give feedback on task completion, coherence, organisation and language use in student work. After a teacher-led demonstration in class, students can use such AI tools for selfstudy, a practice that will also encourage learner autonomy in test preparation. Linguistic improvements Why not ask your student to write something, and then get AI to polish its linguistic features? They can then compare the improvements to their original work. Students can get AI to give feedback on various aspects of writing, such as grammar, syntax, lexis, organisation, coherence, cohesion, redundancy and mechanics.

Overall, when incorporating AI in learning, make sure AI use supports educational goals you intend to meet by focusing on improvement, developing

learner autonomy and using human agency to make the final decision (ETS Research Institute, 2024).

Ethical considerations

Beyond such concerns as plagiarism and disruption to learning are much deeper ethical issues that need to be considered regarding AI use for teaching and learning purposes. One issue is the hidden bias and discrimination in AI output. Since generative AI training data is the Internet itself, which contains a great deal of biased information and discriminatory language, AI has the potential to generate content that may be deemed unethical and offensive. What is interesting is that such bias and discrimination mostly occurs toward already discriminated-against groups since minorities, marginalised communities or the Global South have limited presence and representation online. Since AI mirrors dominant worldviews, teachers should encourage students to be critical of AI output (Fengchun & Holmes, 2023).

With such technology having the potential to deeply impact education and integrity, it is critical to take the first steps into ‘taming’ it to make sure the impact does not go beyond what is controllable. AI technology is here to stay, and it will only get better, keener and stronger in time. We need to make informed decisions now about how we use AI because the

improvements in AI technology are heralding big changes in all aspects of life. With all its potential risks that make us refrain from ever including it in our teaching, let us also keep in mind that it has a lot to offer to facilitate learning and teaching processes.

Code. (2023). AI 101 for Teachers. Code code.org/ai/pl/101

ETS. (2023). ETS R&D. ETS www.ets.org/ research/ai-labs.html

ETS Research Institute. (2024). Responsible use of AI in assessment. wwwvantage-stg-publish.ets.org/Rebrand/pdf/ ETS_Convening_executive_summary_for_ the_AI_Guidelines.pdf

Fengchun, M., & Holmes, W. (2023). Guidance for generative AI in education and research. UNESCO. www.unesco.org/ en/digital-education/artificial-intelligence unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/ pf0000386693

Ghafar, Z. (2023). Teaching writing to students of English as a foreign language: The Challenges Faced by Teachers. Journal of Digital Learning and Distance Education, 2(2), 483–490. doi.org/10.56778/jdlde. v2i2.123

pwesterhuis@etsglobal.org selibal@etsglobal.org

In this article, Roslyn Young presents the work she has done in the Silent Way tradition, an exploration of learning to speak and speaking to learn

In this article, inspired by my work in the Silent Way tradition, I present a different way of thinking about how people learn and teach languages, captured in the twin aspects of the title, ‘learning to speak, speaking to learn’.

Knowledge vs know-how

Let’s begin with a story, a true story which takes place at various times, in many cultures and in different disciplines.

One day, a youth became apprenticed to a master craftsman, a carpenter. He spent some days in the workshop doing menial tasks, observing all that took place. Soon he was given more important tasks. His master used a coaching process; showing him the gestures he had to learn, watching how he worked, and commenting, showing him good practice. Hold your plane like this. It has to be completely flat and level; otherwise, you’ll bite into the wood. Careful of the pressure … Press a little harder with this hand ... That’s better.

Our apprentice’s principal way of knowing was through hundreds of experiences gradually accumulating to become his experience: which gestures are required for each tool, how to adapt them to the various woods, etc.

He became skilled in his craft and proved this by creating his masterpiece; he had become a master craftsman. He began to take apprentices himself and the process started over again. It has been repeated down through the ages, in some countries, to this day.

One day, an idea came to the master craftsman. He would write a book about his craft. To do this, he had to describe many things which, when in the workshop, were evident. He had to describe the tools and the gestures each tool required, the woods he used for different jobs, and so on. The master craftsman converted his knowhows into knowledge. The book was duly published and placed in libraries, the role of which is to hold a culture’s knowledge, and thus made accessible to all.

Many years later, I become interested in woodworking. I find several books on the subject, all descendants of the first

Before retiring, Roslyn Young taught English and sometimes French for many years at the Applied Linguistics Centre of the University of Franche-Comté in Besançon, using the Silent Way and techniques derived from it. You can see her using the Class Conversation technique for Dogme-like guided, free conversation on YouTube.

book written in my culture by a master craftsman. Reading these books and, more recently, watching YouTube videos, give me the same thing: knowledge. Knowledge gives me an entry point into the challenge, but it doesn’t give me what is essential in learning new skills: experience.

I need to get a feel for my tools, the angles to hold them at, the varying pressures they require me to exert. I need to become familiar with various woods, glues, oils … In other words, I, too, need to accumulate hundreds of experiences that will coalesce into my experience and become my know-how. How does one learn know-how? There is only one way, and that is to do it, whatever ‘it’ might be. One accumulates experiences using trials and the feedback they yield to build experience. This is true of skating, of baking cakes or of playing the guitar.

This has always been known: we teach know-how by giving learners opportunities to do ‘it’ and by giving them feedback. Speaking is an activity; it’s something we do. Learners need to keep their wits about them to develop a linguistic agility in the new language. They need to develop a physical agility, the motor skills to use their mouths differently. For the time it takes you to read this article, I would ask you to entertain the idea that, for teaching purposes, speaking a foreign language is best seen as know-how. The takeaway Knowledge does not spontaneously change into know-hows. The only way to learn a know-how is to do it until you know how.

In 2018, an overview of the scientific understanding of learning wrote:

‘Quite literally, it is neurobiologically impossible to think deeply about or remember information about which one has had no emotion because the healthy brain does not waste energy processing information that does not matter to the individual.’ (National Academies of Sciences, 2018, p. 29)

Textbooks try to be relevant and engaging, but nothing in a textbook, no role play, no exercise, will ever have the emotional charge of even the simplest sentence said by someone because this is what they want to say.

In both cases, words come out of a student’s mouth, but only in the second case is language being used as we use L1, with genuine self-involvement. This is real speech. Without self-involvement, we might call what is being produced ‘sp.ch’ (speech with its heart missing). Sp.ch is only a pretence of speech.

When talking about schoolchildren, Holt (1983) wrote:

‘It can’t be said too often: we get better at using words, whether hearing, speaking, reading, or writing, under one condition and only one – when we use those words to say something we want to say, to people we want to say it to, for purposes that are our own’ (p. 124). This is just as true for L2 students. The takeaway Learners’ emotions must be engaged. This will always be the case if they speak about what they choose to, but rarely the case if the teacher makes the choice.

Ferdinand de Saussure is considered to be the father of modern linguistics. He defined the boundaries of the discipline by proposing two entities: a formal system of elements such as syntax, semantics, morphology, etc. which he called langue, usually translated as language; and a second entity, used by humans in the messy business of talking, which he called parole, usually translated as speech (Saussure, 1983). The discipline of linguistics is concerned with Saussure’s langue and formally excludes speech

The problem is that we teachers have been trained in grammar, syntax, phonetics, all part of Saussure’s langue. But our students have come to class wanting to learn parole, the know-how

Issue 290 2022

2022 2019 to speak the language. They are given examples, rules and grammar points and then practise these with exercises where they use (emotionless) sp.ch. It is expected that this will turn into a capacity to produce parole, natural spontaneous speech. The fact that so many students are tongue-tied in real life when they have to speak shows us that working this way is unsatisfactory. This should not surprise us. In no other field are know-hows taught from the rules backwards, or from pretences rather than the real thing. We don’t tell children to pretend to play football before giving them a ball and letting them play. Why demand that students pretend to speak?

As Wittgenstein (1953) pointed out, children learn games by playing them. The rules are made explicit, if ever, only when this is necessary. What happens is that every time a rule is broken, new players see the consequences, and this is enough for them to pick the game up.

The same approach in language teaching is to view L2 as know-how and to use parole – real speech – directly; no rules, no explanations, no teacher talk, just students using the language in sentences generated by themselves. The teacher acts as both referee and coach; referee when telling students that their sentence is outside the boundaries of the language, and coach when helping them to formulate correctly what they want to say. The teacher does this by giving feedback after every sentence, helping the student to get to a final correct form before the next one is said.

The takeaway To learn to speak, learners need to speak and to receive feedback.

Imagine that you are an ice skater learning to perform an axel. You jump ten times and then your coach tells you, ‘Your third try was the best; your left hip was high and you jumped outside your circle. Well done.’ This commentary is much too late to serve any purpose. To be useful, feedback must be given immediately after each trial.

In a language classroom, one of the main jobs of the ‘teacher as coach’ is to provide useful feedback. Each sentence should get feedback as soon as it is finished. This does not mean simply reformulating the student’s version. Nor does it mean correcting what students can rectify for themselves. It does mean the more subtle process of developing their criteria so that they understand what misconception(s) created any problems. It also means introducing new language where this is needed for students to properly express the idea they have in mind. Lessons like these are the

Wednesday evening ‘training session’ with the coach, as opposed to the ‘playing the game’ session on a Sunday afternoon when people simply talk to each other. Giving precise feedback economically requires tools. The tool we use most is finger correction; one word for each finger. This is intuitive and easy. Fingers can be waggled, grouped, folded and crossed. Fingers are used to guide learners as they reflect on what they say. It is so useful that many students start using their fingers to reflect on their productions.

The takeaway

Timely feedback is essential in the learning process.

Languages give their speakers different ways of talking about the world: Japanese speakers don’t talk about the world as French speakers do or as English speakers do. Japanese manages with no articles, no plurals, no gender, and rarely uses pronouns; how is that possible? French speakers use many pronouns; not only that, they cram them all into the beginning of their sentences. How do they manage? English speakers can ‘put down’, ‘put up with’, ‘put one over’, and so on. How strange! We call these fundamentally different modes of expression ‘the spirit of the language’, those things that make each language uniquely foreign.

Discovering the spirit of a language directly, from the beginning, generates astonishment and a desire to find out more. As one learner put it, ‘I love

learning Japanese. It’s SO foreign!’ The excitement appears where the foreignness is most apparent, with the use of the functional vocabulary. The lexical vocabulary comes easily when introduced later, once this core has been explored.

The takeaway

Learning is exciting and inviting when students meet the language at its most foreign. We exploit this.

Just as the master craftsman guides his apprentice by giving him experiences that build into experience and become know-hows, so teachers working in the Silent Way tradition guide their learners sentence by sentence until they reach a know-how-to-speak-the-language. In doing this, we teach students what they came to class to learn.

Holt, J. (1983). How children learn Pelican.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures. The National Academies Press. doi.org/10.17226/24783

Saussure, F. (1983). Course in General Linguistics. Duckworth. (Original work published 1916) Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell.

roslyn.young@orange.fr

Following on from Roslyn Young’s article on the Silent Way teaching methodology, Laurence Howells presents an interview he conducted with her about her work

Since retiring as Chief Executive of the Scottish Further and Higher Education Council in 2016, Laurence Howells has focused on teaching and learning languages, producing over 150 educational films for silentway. online. He is currently learning Japanese, French and Spanish. Introduction

This article is based on an interview with Roslyn Young in January 2024. Roslyn Young is an expert on teaching languages. She has 60 years’ experience teaching English and French and she has written extensively on learning and teaching and their application in the foreign language classroom.

A Class Conversation is just an ordinary conversation, except that the students are speaking in the language they are learning. So the students provide the content of the lesson – whatever they want to talk about from their lives, interests and concerns –and the teacher helps them to express it in good quality English.

A student launches a sentence – it could be a question or something they want to tell people about – and the teacher works with this student and the rest of the class to turn this attempt into correct, wellpronounced English.

It is this process, undertaken sentence-by-sentence that makes it a lesson. Without this, it would be just a conversation in poor English: students can do that by themselves outside of class. Class Conversations are not for beginners. Students need a solid base in pronunciation and the ability to use the functional vocabulary at intermediate level.

How does the teacher build the course around the students’ needs?

Students of English invariably have problems with pronunciation and almost always with the English system of verb tenses. As a result, these become the focus of the course. And because the functional vocabulary comes into every sentence, students also work on this. Sometimes, they will need new vocabulary. Therefore, the teacher needs the skills and tools to work with students on these things.

If students are to learn, every sentence must be worked on until it is correct. As far as possible, the teacher should guide the student, together with the rest of the class, to do much of the correction themselves. The teacher helps by first showing only where the problem lies, and then by offering hints if necessary. When the sentence requires linguistic knowledge the students don’t have yet, the teacher provides what’s needed.

The process of working on sentences is done as a whole class activity because everyone learns from observing the process unfold. And if the whole class is kept together, attentive and involved, everyone gets full benefit from the lesson.

How many students can you have in a successful

It’s preferable to have at least ten students because that makes for variety in the conversations, but Class Conversations can be run with any class of more than one student. If the teacher has more

experience, then classes of 20–30 students can easily be run. The largest group Roslyn Young ever taught was a group of 55 students on a week-long summer course for English in August 2010.

started?

Students new to this way of working need help to get started. So the teacher seeds the first few Class Conversations with questions like: ‘What did you do last weekend?’ or ‘Where are you from?’ These are simple, open-ended questions that members of the class can ask each other and that everyone can answer. Each answer will be different and personal, and they can be answered at many levels of detail. As they gain confidence, students learn to follow up if an answer intrigues them. They also learn to come to class with something to tell everyone.

After the first few Class Conversations have been launched, all the teacher has to do is make an encouraging gesture and wait until people have had time to think of their first sentence.

Intermediate students need the skills to express themselves about simple things – their everyday lives and activities –spontaneously and with ease. This is the priority at their stage in learning a language: more complex things will come later. The ease they gain from speaking about their lives and listening closely to their classmates doing the same gives them confidence in speaking English. To

Working on the English verb tense system, August 2010

see this idea in action watch this video

In a sufficiently long series of Class Conversations, the class will encounter all the common structures and most of the common vocabulary they need for everyday conversation. This is normal; the common things occur and recur because they are common!

Nothing is more interesting than humans. And all our students have stories to tell, even if they’re only about their hobbies or holidays on their aunt’s farm or what happened on the way to the dentist yesterday. Stories that seem unimportant … But telling their stories turns them from a group of students into a group of people; people who have lives, histories and dramas. This is what we want as teachers.

We don’t want them saying things they have no emotional engagement in. If they have no personal investment in what they’re saying, their brains simply won’t deal with what’s being worked on and the lesson will leave no lasting impression.

This means talking about themselves, always telling the truth, asking other people about themselves, and expecting to hear something truthful about them and their lives.

‘The content most likely to engage learners and to trigger learning processes is that which is already there, supplied by ‘the people in the room’. (Meddings & Thornbury, 2013)

Conversation invented?

The circumstances around its invention were very particular. Roslyn Young taught a week-long English course in 1978 near Lyons in France. The class was made up of a closely-knit group of about 35 primary school teachers from France and Switzerland who were using Caleb Gattegno’s approach in their teaching

(for more information see: silentway. online/). They had been working together for nearly ten years, one full weekend each month. This was a group of friends, including the teacher herself, and the level of trust was therefore exceptionally high. At one point around mid-week, the students just started taking the class over, talking and joking in English, and Roslyn simply followed them. She worked sentence by sentence with the students to correct what they’d said; the essence of the Class Conversation was created.

From the early 1980s, it was used systematically by a group of eight teachers at the Centre de Linguistique Appliquée at the University of FrancheComté in France. This team developed specific tools and techniques to make it more effective, and it is still in use there.

All classes have people at different levels. How can the teacher deal with this?

Pronunciation is the great leveller. It is advantageous to teach pronunciation as a motor skill (for more information see: www.pronunciationscience.com/); it is much more efficient than any ‘listen and copy’ process. The teacher can then demand a much higher standard of pronunciation from the faster or more advanced students. This means they keep improving. It also means that the weaker students hear better and better pronunciation from their classmates, and learn from observing how it was achieved.

You can get the faster students to make more complex sentences. For example, they can be asked to take the last few sentences and find ways to combine them into one longer one or to find different ways of expressing the same meaning as intended in the current sentence.

You can also send them off into a corner of the room to practise saying their sentences several times. When they come back they may want to say the sentence again so that the teacher can check it or deal with any doubts they have. Even the more advanced students find that complicated sentences can’t be pronounced fluently and accurately without practice. While these students are doing work like this, the teacher can give more time to others in the class.

How do you deal with students who don’t want to say anything? Or those who never stop talking?

Reticent students often just need encouragement and time to get used to the situation. But if after a lesson or so,

despite being given opportunities, they still haven’t spoken, then they can be taken aside and you can say, ‘Do you mind if, for the next lesson, I tell the rest of the class “We don’t know much about X. So today, let’s ask him (or her) and find out as much as we can”’. The student concerned invariably says ‘Yes’ and that is usually all that is needed to get them launched.

Very occasionally this doesn’t work. But then it becomes the student’s problem. We can only continue to give them opportunities and encourage them. People sometimes have to deal with difficult issues in their lives and we have to respect that.

Very loquacious students can be taken aside and made aware that they are using more than their fair share of ‘airtime’. They can also be held in check by limiting their participation to only asking questions or seeking more details. This can have the added advantage of keeping the conversation going.

Taking notes in a Class Conversation isn’t permitted. All the students need to be completely present to what’s going on in class all the time. There are all sorts of subtle things going on as the class works: little gestures, movements of eyebrows, smiles and frowns, tones of voice … and the students need to be aware of these. This goes beyond the details of work on the language: if the class is meeting as people, then they need to be aware of each other as people. Taking notes breaks that awareness and divides their attention in a very damaging way.

In fact, notes are simply not needed. If the work on each sentence is properly practised, then the learning has already been at least partially lodged where it needs to be – in students’ minds, and not on pieces of paper. And then, the process of sleep will naturally consolidate the work in each student’s mind.

Reference

Meddings, L., & Thornbury, S. (2013). Teaching unplugged: Dogme in English language teaching. Delta.

Laura Hadwin examines the use of feedback in the classroom and presents various activities that can be used to provide meaningful feedback to learners

‘Feedback is a free education to excellence. Seek it with sincerity and receive it with grace.’ – Ann Marie Houghtailing

I’ve been incorporating informal feedback activities in my English language classes and improving my teaching as a result. As teachers, we are continually giving feedback to our learners so that they can improve. It is equally important that we elicit feedback from our learners about their learning so that we can further help them improve. The more information we have about their strengths and challenges, the better we can help them. Additionally, we need to know their perceptions of our teaching, the activities and materials. Feedback fatigue is real! I’m rarely surprised nowadays when I get asked for feedback after buying sweets or vitamins! The feedback activities I have designed and selected are short and sweet, and I’ve also tried to incorporate a healthy dose of creativity to make them more engaging!

Feedback activities: design

Feedback activities in teaching and learning are referred to as Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs) in adult education (andragogy). I have adapted guidelines from Classroom assessment techniques (Angelo & Cross, 1993, p. 26).

1 Is the CAT context-sensitive? Will the assessment provide useful information on what a specific group of students is learning about a clearly defined topic at a given moment in a particular classroom?

2 Is it mutually beneficial? Will it give both teachers and learners the kind of information they need to make changes and corrections to improve teaching and learning?

3 Is it easy to administer? Is the assessment technique relatively simple and quick to prepare and use?

Laura Hadwin is an English language instructor at Camosun College in Victoria BC, Canada. She is interested in teacher beliefs and identity, materials design as well as creativity in teaching and learning. She has taught and delivered teacher training in South Korea, Spain, the UK, Turkey, Qatar and Mexico. In her free time, she enjoys yoga, volunteering and exploring our beautiful world!

4 Is it easy to respond to? Is the feedback that results relatively easy to organise and analyse?

5 Is it educationally valid? Does it reinforce and enhance learning of the specific content or skills being assessed?

I have organised the feedback activities from more to less controlled. They can be modified or adapted to suit specific teaching and learning contexts. Feedback from learners about their progress can also be combined with feedback for the teacher about the teaching, materials and activities. I use post-it notes, recipe cards or cut-up pieces of coloured paper, and I usually get feedback at the end of the week or the end of a unit.

Two-or-Three Sentence Summary

(adapted from Angelo & Cross (1993), p. 183)

Learners can focus on whatever has emerged that week in relation to their learning and/or the teaching. A more general holistic approach can produce revealing insights; however, paradoxically, it can also generate formulaic or unspecific responses. Training learners on providing feedback before moving on to more open feedback is a useful strategy. If there is a particular area the teacher or learners want to address, it can be the feedback focus, for example, speaking or group work. Some educators argue that feedback should be separate from instruction, but I see many opportunities to incorporate and review learning, particularly as I get feedback frequently, making it lower stakes. Learners can be encouraged to write compound, complex or compoundcomplex sentences to practise writing skills. I usually make feedback

anonymous, but it can still be errorcoded and handed back the next day for learners to correct, regardless of whether it was theirs. This workshopping of the language should occur after the teacher has gone over key trends in the feedback and discussed how it will be addressed in subsequent lessons.

(adapted from Angelo & Cross (1993), p. 154)

Muddiest Point requires learners to identify the area they are most confused by. Teachers are often time-pressured and cannot do much individual concept checking; Muddiest Point is popular as it quickly and easily allows the teacher to identify what learners are unsure about. Learner-generated feedback requires learners to take ownership of their learning, thereby promoting autonomy. It also allows them to feel heard, which promotes agency. Additionally, reflection and noticing are key components of independent learning.

This traffic light analogy uses green, orange and red to inform the teacher of what areas learners are confident about, unsure about or feel they need to improve. For teacher feedback, I use ‘Start, Continue, Stop’. Both modes of feedback are very direct and clear. Learners can also complete the feedback on post-it notes or cut-up pieces of green, orange and red paper.

Like a one-to-five star online review, learners assign stars to teaching and learning categories. For learning feedback, this could include the four skills (reading, writing, listening and speaking), vocab, pronunciation and grammar. For teaching feedback, it could include materials (handouts, coursebooks, online resources, cards, etc.), assessment, activities (games, tasks, role plays, projects, etc.), group work (pairs, groups or whole class), classroom dynamic and atmosphere, use of technology, timing and flow, organisation of the week, classes or activities, homework, etc. Learners can address specific categories or choose which ones they feel strongly about from a list.

A variation on Star Ratings is Rankings, where learners rank the top three to five areas for learning and/or teaching

Issue 290 2022

2022 2019 feedback. Evaluation is a higher-order thinking skill, and practising it is useful for transfer to other contexts. As in Star Ratings, eliciting the topics from learners encourages deeper engagement with their learning. Encouraging them to support their responses will yield richer feedback and provide more opportunities for targeted future action. Requiring elaboration strengthens critical reflection and highlights the importance of substantiating our ideas.

Graphic Organisers

Graphic organisers provide flexibility in gathering feedback. They also allow for considerable adaptation and creativity.

❚ Mind Map: A basic mind map shaped like a cloud with lines emerging from the centre can be used, or the teacher can modify the organiser to complement the topic. For example, if the unit is on food, the organiser could be designed to look like a type of food, or if it is on nature, it could resemble an animal. This unifies the content and learners can decorate their organisers as well.

❚ SWOT: This graphic organiser is borrowed from business. SWOT stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This method combines student perceptions of their ability (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (opportunities and threats). The opportunities and threats could include the teacher, institution and wider world. It is wonderful for ELT to borrow from other disciplines – many activities in general education training sessions, such as icebreakers, fillers

and revision games have been used in ELT for decades!

❚ T-Chart: Learners list pros and cons or strengths and weaknesses of their skills or the course. It is crucial to be very clear when seeking feedback on teaching (I have used ‘challenges’ and ‘weaknesses’ to get feedback, and learners list their language limitations rather than identifying areas for improvement in teaching).

GLAD(S)

GLAD stands for grateful, learned, achieved and delight. I do a daily GLAD in my diary, and it can be based on teaching, my personal life or a combination of both. There is strong evidence to support a gratitude practice in positively affecting mental health, which is particularly relevant nowadays. I therefore think it is key that learners celebrate their successes and cultivate joy in their learning. Later, I also encourage them to start doing GLAD outside of class to boost their moods. I do my GLAD in Spanish, and I show learners how these small L2 moments add up to greater language acquisition. Teacher modelling of selfcare and language learning strategies demonstrates authenticity and credibility.

The teacher can set up this activity on post-it notes with learners posting their notes on the whiteboard and reading one another’s posts. With this variation, it is key to tell learners that they will be posting their responses for everyone to read. I have also added an ‘S’ for struggle to get learners to reflect on their challenges. Supporting one another with challenges is motivating, inspiring and

promotes a growth mindset. Analogies

Analogies is adaptable to the content/ topic and involves learners creatively reflecting on their learning. The teacher provides sentence stems such as:

1 After this week’s class/this topic, I feel like X because… Learners choose a famous contemporary/historical figure, celebrity, politician, etc. and explain why they feel like the person they selected.

2 Additional variations: I feel like x animal/fruit/city/movie because…

The most crucial part of feedback is that it is acted on. Learners must know that there is a purpose to their providing feedback. I go over the feedback during the next class and I reiterate why feedback is important. I discuss trends that emerged and outline what I plan to do to address these areas. Later, I make a clear link between the classroom activities we are doing and the feedback. I recently did Traffic Lights, and a couple students requested that I continue doing these feedback activities! If you have any other engaging feedback activities you would like to share, please email me.

Angelo, T. & Cross, P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques. Jossey-Bass.

hadwinl@camosun.ca

Vanessa Rodrigues Bocchi Barbosa discusses the concept of Positive Discipline and explores how it can be incorporated into the classroom

Teaching requires commitment beyond the content. One should always strive to reduce the distance between what is said and what is done. ‘Freedom matures in confrontation with other freedoms, in the defense of its rights against the authority of parents, teachers, the state’ (Freire, 1996, p. 106). Belonging is achieved through the perception of belonging to a group, not by a simple physical presence, but as an integral and participative part of the whole, taking into account its real importance in the functioning of the interpersonal fabric. The child belongs and responds when he or she feels that his or her participation is important, necessary and valued by the adults (Nelsen, 2017).

It goes without saying that being able to work in a good atmosphere creates more learning opportunities and provides students with a sense of belonging. Nelsen (2017), in the approach proposed by Positive Discipline, explains and details the basic concepts of Adler’s (1956) theory, emphasising the following premises: children are social beings; the child’s behaviour is based on self-created goals; the child’s main goal is to be accepted; a child who does not behave is always a discouraged child; it is necessary to have a sense of social responsibility; the practice of equality is fundamental; all mistakes are learning opportunities; and still, the need to show affection unequivocally.

Positive Discipline is a model of encouragement based on 5 principles:

1 Be firm and gentle at the same time.

2 Make the child feel important and relevant.

3 Be effective over the long term.

4 Teach life skills.

5 Help children develop skills and become aware of their resources. (Nelsen, 2017) All principles are simultaneously important through interdependent approaches in no order of importance.

If we consider the curriculum and the school environment as tools and spaces

Vanessa Rodrigues Bocchi Barbosa has been in ELT for over 20 years. She has a master’s degree in education: curriculum (2021) from PUC-SP, is graduated in Literature (Portuguese and English) and Education and has a degree in Social Communication. She holds the CELT-P and the TKT-YL. She has been a Positive Discipline educator since 2017. She is currently a pedagogical and internationalisation coordinator at Colégio Marista Arquidiocesano in São Paulo, Brazil.

that promote the integral development of the student, we have the need to expand the possibilities in this environment and qualify the interactions between the beings that belong to such an environment. Malaguzzi (1999) teaches us to think about the potential of children and to respect their rights. Moreover, pedagogy must focus on the child as the protagonist and creator of his or her learning, with the teacher acting as a mediator who guides and accompanies the child (Malaguzzi, 1999).

Positive Discipline believes that children learn when they are taught gently and firmly at the same time, without the use of punishment. Its contribution to education is to change the way adults look at children and to emphasise the need to create a culture of respect and belonging in the way people are educated.

We have seen many developments in methods over the years. However, the foundation for a mentally healthy person has never been the focus, as the content of the teaching has always been placed in the foreground in schools. The search for an inclusive curriculum includes the student, which can be achieved through the Positive Discipline approach.

In the context of education through Positive Discipline, the student is always seen as an integral part of the relationship in its totality, deserving respect in treatment, appreciation of language, a sense of belonging and the need for their contribution to the social group. The child is perceived as part of the discourse in a truly equal position; one speaks with them, not about or for them.

The success of Positive Discipline depends, to a great extent, on the mutual

connection and interactivity between the adult and the child in an environment of respect and equality. The application of the Positive Discipline approach depends on the adult learning new skills to help children achieve safety, belonging, acceptance, equality, affection, encouragement and social responsibility, both in childhood and in adult life (Nelsen, 2017).

One of the helpful and practical rules of Positive Discipline is the development of respectful communication skills. This is because development is continuous and the way we communicate can be both a communication barrier and a communication stimulator. Phrases like, ‘This is your fault!’, ‘How many times do I have to discuss this with you?’, ‘When are you going to get your act together?’ are clear behavioural barriers. However, phrases like, ‘I’ve noticed you were uncooperative today. I am interested in hearing your version of what happened.’ ‘Can you think of ways to avoid this problem in the future?’ and ‘If you need help with this problem, let me know. I can think of some ideas.’ stimulate communication. According to Nelson, ‘It is necessary for educators to phrase their sentences in a way that encourages communication in context’ (2017, p. 78). Examples of communication barriers include:

One should not assume what the student thinks, feels or knows. As obvious as it may seem, educators often try to guess what the student knows, thinks or feels without asking. Such a habit leads to missed rare opportunities, as the student may be underestimated or misunderstood without even being given a chance to communicate.

Dreikurs suggested that it is best to never do anything for a child that the child can do on their own (Nelsen, 2017). Exploration is always necessary for the child’s development and therefore the educator must always find ways to provide opportunities and create situations for students to think about themselves

Issue 290 2022

2022 2019 and draw their own conclusions rather than telling them what to do and how to do it.

Like explaining, instructing reinforces a pattern of dependency. Students should be encouraged and involved so that they can all come to conclusions about how to make the classroom a healthier environment for all.

anticipation instead of celebrating

Teachers should have high expectations. But they should also celebrate all successes, even the smallest ones.

Children have priorities that are appropriate for their age group. Therefore, even though adults should be teaching languages, history, science, etc., they should show understanding and respect for other activities such as sports, friends, sleeping, etc. (Nelsen, 2017).

By getting familiar with the principles of Positive Discipline, little by little the teacher starts to benefit from it by gradually building a relationship of mutual respect with the students. Of the many practical ways teachers can:

1 ask rather than explain;

2 suggest limited choices;

3 redirect situations;

4 act without speaking/agree on nonverbal signals;

5 use encouraging phrases;

6 use class meetings with students; and/ or

7 make a connection before correcting.

The possibilities are many. Through daily practice, the teacher will become better at applying the techniques and understanding the reason for the student’s behaviour, making the classroom more productive and welcoming. Positive Discipline offers the opportunity to enhance teacher training while promoting the emotional growth of students and it does this by

developing self-regulation and highly relevant emotional skills for everyone in education.

Adler, A. (1956.) The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler. Harper. Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogia da Autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa. 25 Edition. Paz e Terra.

Malaguzzi, L. (1999). História, ideias e filosofia básica. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G. Forman. As Cem Linguagens da Criança: a abordagem de Reggio Emilia na educação da primeira infância (pp. 59–104). Artmed. Nelsen, J. (2017). Disciplina Positiva: O guia clássico para pais e professores que desejam ajudar as crianças a desenvolver autodisciplina, responsabilidade, cooperação e habilidades para resolver problemas Manole.

vanessa.bocchi@colegiosmaristas.com.br

Romina Sabia looks into unlocking the potential of artificial intelligence for personalised learning and encourages educators to take the leap

In my dynamic and ever-evolving role as an English teacher, I have recently embarked on a transformative exploration into the boundless and exciting realm of artificial intelligence (AI). The world of AI, with its innovative technologies and cutting-edge applications, has unveiled thrilling possibilities, promising a more personalised, engaging and collaborative learning experience for my students. Through this reflective article, I am eager to share the enriching experiences AI has brought to my teaching practice and express my unwavering enthusiasm for the ongoing integration of AI in the classroom. My aim is to inspire and empower fellow educators to overcome any apprehensions and embrace the incredible opportunities AI presents for the future of education.

My introduction to AI: a paradigm shift

The moment of my first encounter with AI remains vivid in my memory – it felt like stepping into a new world teeming with limitless potential. As I ventured into the paradigm shift, I incorporated ChatGPT, a sophisticated conversational AI, as my virtual teaching assistant. This AI not only efficiently addressed student queries but also dynamically generated content and provided real-time feedback, infusing a new level of dynamism and personalisation into my teaching approach.

As my exploration of the AI landscape deepened, I discovered specialised history education chatbots like ‘Hello History’ and ‘Próceres.ai’. These digital companions not only facilitated seamless communication but also sparked lively historical discussions, offering my students instant access to a wealth of valuable information. The ease with which these chatbots integrated into my lessons was astounding, opening new and exciting avenues for interactive learning experiences.

Romina Sabia is an ESL Teacher at IES en Lenguas

Vivas Juan Ramón Fernandez. She is a MagicSchool AI Trainer and AI Consultant, and is a member of the Parlamento Mundial De Educación. Romina is also a member of SAIA (Sociedad Argentina de Inteligencia Artificial).

A groundbreaking revelation in my AI journey was the discovery of AI-generated visuals and videos. Platforms like D-ID, dedicated to anonymising facial images and videos, streamlined the management of sensitive student data, revolutionising privacy protection in the digital classroom. This technological marvel proved to be a gamechanger, ensuring a secure and

ethical environment for both educators and students.