Volume 4, Number 1 (December 2024)

Publication date: December 2024 [online] an IATEFL Teacher Development Special Interest Group publication ISSN Number 2957-4374

Publication date: December 2024 [online] an IATEFL Teacher Development Special Interest Group publication ISSN Number 2957-4374

The goal of the TDAJ is to provide an open-access platform for teacher development-specific evidence-informed articles which is published and can be read by the wider ELT community. For this, TDAJ requires both academic rigour and the use of accessible language to express ideas. TDAJ is a prime example of teacher development on its own: in addition to experienced researchers, we encourage new writers to reflect on their own practice and share ideas of good practice regarding teacher development topics; we provide writing and editing support where useful. For more information about this and regarding becoming an author, please visit tdsig.org/tdaj.

We would like to thank Bridge Education Group. Cambridge University Press & Assessment and NILE for their support, which makes it possible for TDSIG to maintain all our initiatives, including this publication.

Article types

We accept articles of varying lengths to appeal to a wide variety of readers and to accommodate a wider variety of content. In this issue, you’ll find that excluding references, tables, and appendices, articles fall between:

● shorter: 1500-2500 words, and

● longer: 3500-5000 words.

We also recognise and value different types of approach to information dissemination from author to reader. As a result, though quality must meet standards expected and articles undergo a peer-review process, we welcome articles that include research, commentary, and informed practice.

Key themes

As we aim to be distinct from publications by other IATEFL special interest groups, we welcome referenced articles which primarily focus on aspects of teacher development involved in one of the following categories:

● Bottom-up Teacher Development (e.g. lesson observations, personalized professional development plans, teacher empowerment, etc.)

● Teacher Identity (i.e. how teachers’ beliefs/attitudes and different identities affect teacher development and teaching)

● Teacher as researcher (i.e. ways in which research can be a teacher development tool)

● Mentoring (e.g. Induction/orientation programs, mentoring novice/experienced teachers)

● Pedagogies (e.g. developing inclusive, critical, etc. pedagogy into one’s practice)

TDSIG committee

The TDAJ editorial team consists of volunteer members of the TDSIG Committee with the support of volunteer reviewers from the TDSIG community where required.

TDAJ Subcommittee: Kirti Chandra, Elizabeth Coleman, Cecília Lemos Harmer, Jake Kimball

TDSIG Committee: Kirti Chandra, Elizabeth Coleman, Cecília Lemos Harmer, Maria Eugenia Ianiro, Jake Kimball, Taíza Lombardi,Kristina Novik, Didar Moldazhanov, Helen Slee, James Taylor

Copyright notice

Copyright for whole issue IATEFL 2024. IATEFL retains the right to reproduce part or all of this publication in other publications, including retail and online editions as well as on our websites. Contributions to this publication remain the intellectual property of the authors. Any requests to reproduce a particular article should be sent to the relevant contributor and not IATEFL. Articles which have first appeared in IATEFL publications must acknowledge the IATEFL publication as the original source of the article if reprinted elsewhere. Published by IATEFL, 2-3 The Foundry, Seager Road, Faversham, ME13 7FD, UK. www.iatefl.org

Disclaimer

Views expressed in the Teacher Development Academic Journal (TDAJ) are not necessarily those of the editor(s), of the IATEFL Teacher Development Special Interest Group, or its staff or trustees

To these and future authors

TDSIG sincerely thanks all the contributing authors for their hard work and commitment to teacher development in ELT and choosing to share their ideas, qualitative and quantitative research, and commentaries in this volume of the TDAJ. Without you, our journal would not exist.

If you are interested in contributing your work to a future volume of the TDAJ, please visit our website (tdsig.org/tdaj) where information on submissions is located. We aim to publish at least one volume every year.

Foreword: Teacher change over time

Jake Kimball 7

Differentiated instruction in an English as a second language class

Daniela Gonçalves de Araújo Antoniazzi 8

The impact of coaching in educators’ development: Documenting change and progress

Pablo Molina Byers 21

Mentoring: facilitating and developing a positive mentee experience

Richard Cowen 37

Student engagement in classroom activities in pre-service EFL teacher education programmes

Turaeva Guzal Tojidinovna

47

Reimagining mentorship: Navigating teaching realities in remote areas

Patricia Ibiapina 57

Teachers as leaders in action research

Ljerka Vukić and Grazzia Maria Mendoza-Chirinos 63

Teaching English during the War: Changing and Documenting the Changes

Nataliia Krynska, Olena Rozdolyanska and Yaroslava Litvovchenko 69

Jake Kimball

Change is an inevitable part of life, and that change is the heartbeat of personal growth and progress. This concept of change is especially relevant to us as teachers. In the world of education, we are at the forefront of an ever-evolving landscape. Context matters little. From dusty classrooms with chalkboards to ones blessed with interactive smartboards. From traditional teacher-fronted lectures to communicative, student-centered activities. From mentee to mentor. Our journey as a teacher is one marked by continuous transformation.

Teacher Development Academic Journal (TDAJ) Volume 4 focuses on "Action Research –Developing and Documenting Change." It explores the dynamic nature of our teaching profession. It is a tribute to the resilience and adaptability of TDSIG members who constantly evolve. These articles and reflections delve into the challenges and rewards of change. As you engage with this volume, note that change is not so much a challenge but an opportunity a path to becoming an even more impactful and effective educator. You will find reflections on minor adjustments that led to significant classroom outcomes in the face of broader shifts driven by political instability, educational philosophies, and teaching context.

Our contributors provide a nuanced, global perspective on balancing innovation with tradition in a world where societal expectations and technological advancements shift rapidly. We invite you to consider turning points in your own career those moments that have led you to evolve as an educator.

We embrace conversations about change and the profound ways it shapes us, both as individual educators and as a collective within the IATEFL TD SIG community. We are immensely grateful to our contributors who have shared their expertise and pedagogical insights. Their stories serve as both a source of inspiration and a call to embrace the ongoing journey of professional growth, and we are grateful for the insights and experiences they bring to these pages.

We hope you enjoy it.

Jake Kimball has been a member of TDSIG and part of the publications committee since 2023. He edited this volume.

Daniela Gonçalves de Araújo Antoniazzi

Abstract

This paper reflects on differentiation and equity in English as a Second Language classes for high school students at a private bilingual school in the city of São Paulo, where students have different readiness regarding using English as the means of instruction. To achieve this, the teacher should work with a backward design, have a growth mindset, and believe that "all students are smart and can learn provided they have appropriate support" (Cohen and Lotan, 1997). The present research impacted the researcher's teaching practice after finding that although the learning goal should be maintained, sometimes activities, evaluations, and texts must be differentiated.

Introduction

The main objective of this paper is to reflect on differentiation and equity in English as a Second Language classes. To do this, I analysed the works of Cohen & Lotan (1997), Heineke and McTighe (2018), Tomlinson and McTighe (2006), Bondie and Zusho (2018), and Sousa and Tomlinson (2018), among others. This analysis led to a reflection on my teaching practice, referred to in the final part of the text.

Context

In recent years, the city of São Paulo (Brazil) has seen a huge expansion of bilingual schools in its city centre and outskirts. As this is a relatively new phenomenon, bilingual schools are challenged by the necessity of guiding teenagers with varying English as a Second Language (ESL) backgrounds into native-like readers, writers, listeners, and speakers.

Thus, our context is a private bilingual school class in the West Zone of São Paulo, where real beginners and native-like learners study together and must be challenged to enable equitable learning opportunities for each student. More specifically, our study will focus on thirty 9th graders, approximately 14 years old, divided into two mixed-gender groups in non-leveled classrooms. The majority of the students are from a high-income class, although several have scholarships for being children of staff members, and one student has a socioeconomic scholarship.

Furthermore, these 9th graders weekly attend six 50-minute English classes that follow an adaptation of a native American reading and writing program (so that students eventually will be able to read and write a variety of genres) and two 50-minute English classes to work on pronunciation and spelling using a phonics method. Finally, their teacher is an educator with twelve years' experience who truly believes "All students are smart, and all students can learn provided they are given the opportunity and are supported by the teacher." (Cohen and Lotan, 1997, p. 3).

At the onset, we should clarify that despite all being Brazilians, our students can be considered "culturally and linguistically diverse" since they come from different cultural backgrounds (such as religious, race, gender, abilities, etc.) and present different English language levels, as well as unequal opportunities for speaking the target language in authentic contexts.

Having said that, this paper aims to consider differentiation theories and strategies to find those that could be used by English middle and high school teachers working in a bilingual school class and also to research teachers' mindsets and the possible consequences of a biased attitude on their students' academic experience. Moreover, although differentiation can be undertaken from three different perspectives, namely student's readiness, interest, and learning style, we will focus on the differentiation based on student's readiness since it has been the most challenging in the context analysed and the most influential in terms of the teacher's expectations and the students' achievement.

Consequently, the study is motivated by the teacher's personal belief that even learners with an elementary knowledge of English should work on essential knowledge, understanding, and skills for their grades; learners also have the opportunity to develop and demonstrate their reading and writing abilities by reading and writing excerpts from the news, essays or short stories, provided they are supported by the teacher, colleagues, help resources, and differentiated instructions.

Over the years, students and teachers in English as a Second/Foreign Language (ESL or EFL) classes have been experiencing the challenges of a culturally and linguistically diverse class, together with the challenge of providing everyone with an equitable opportunity to learn and benefit from instructions and activities. In trying to solve this issue, much research has been conducted to understand how teachers' expectations of students' performance determine their teaching decisions and differentiating choices, as well as how their choices can impact students' outcomes.

Some of the authors included in the review were Cohen and Lotan (1997, 2014), Tomlinson and McTighe (2006), Celce-Murcia and Snow (2014), Gibbons (2015), Bondie and Zusho (2018), Heineke and McTighe (2018), Sousa and Tomlinson (2018), etc.

To begin with, Sousa and Tomlinson (2018) define differentiation as a learner-centered approach through which the teacher addresses any student who is not ready for the content they are being exposed to and fills students' knowledge, understanding or skills gaps by "moving backward and forward with essential content in order to guarantee real growth to all students" (Sousa and Tomlinson, 2018, p. 8). On the other hand, Bondie and Zusho (2018) cite Tomlinson's 2006 definition of differentiation as "a teacher response to learner's needs guided by general principles of differentiation such as respectful tasks, flexible grouping, and ongoing assessment and adjustment" (Tomlinson, 1999, p. 15, cited in Bondie and Zusho, 2018). Comparing both definitions, the second seems more faithful to our current reality since it considers learners' gaps and students who have already met the learning goals.

Secondly, teachers' expectations of students' performance must be weighed as Rubie-Davis (2010, p. 121) presents studies that bring the self-fulfilling prophecy effect theory, according to which, when teachers expect their students to perform at high levels, they do. Moreover, highly differentiating teachers, who provide different work to students according to their high or low expectations of students' abilities, are believed to send them a message that may contribute to their fixed mindset (Rubie-Davis, 2010, 123-124).

Advocating for a low-differentiation mindset, Heineke and McTighe (2018) emphasize the need to work with backward design and ensure that learning goals and criteria will not be changed based on our expectations of learners' performance. Instead, similarly to Tomlinson and Sousa (2018), they insist we should use a culturally responsive pedagogy in which instructions teach up while the scaffolds consider students' profiles and readiness to allow learners from any culturally and linguistically diverse environment to reach the big idea goal and be able to transfer their acquired knowledge to other areas.

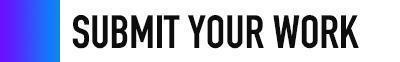

Moreover, they affirm that "to plan instruction that is culturally and linguistically responsive, teachers begin by recognizing, prioritizing, and integrating students' linguistic backgrounds, strengths, and needs." (See Figure 1)

(Heineke and McTighe, 2018, p. 37, Figure 3.1)

Furthermore, according to Heineke and McTighe (2018), even native or native-like students need to be taught the academic language for each discipline they go through, which they refer to as disciplinary language. Knowing that teachers must be aware that proficiency in a second language can be accomplished both by: "1) transferring knowledge and abilities from their diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds; and 2) through social interaction during teachers' strategic integration of scaffolds and supports."(Heineke and McTighe, 2018, p. 25)

Moreover, according to the same authors, as low-differentiating teachers believe all students can learn provided they receive appropriate support, are provided with complex instruction, and are stimulated in a growth mindset, these teachers take responsibility for their students' learning processes by organizing them in groups of interest or mixed-ability,

stimulating mastery goals and intrinsic motivation, as well as viewing their mistakes as an opportunity to learn, encouraging peers to teach each other, while focusing on individual progress and achievements. Therefore, according to Tomlinson and McTighe (2018), classes with positive teachers' attitudes toward students tend to achieve better performance.

Consequently, according to Sousa e Tomlinson (2018, p. 9), the bedrock of effective teaching is:

1. Creating a safe, challenging, and supportive environment;

2. Delineating essential knowledge, understanding, and skills in a content area focusing on high engagement and a teach-up curriculum that will also challenge advanced learners;

3. Using diagnostic and formative assessment on knowledge, understanding, and skills throughout the segment of study;

4. Using ongoing assessment to plan upcoming instructions that will move every learner ahead;

5. Being flexible in working individually with students when needed and guiding students to comprehend the purpose of a differentiated classroom to address students' differences. (Adapted)

Based on the above, 1) an invitational learning environment, 2) quality curriculum, 3) Persistent formative Assessment, 4) responsive instruction, and 5) leading students and managing flexible classroom routines are non-negotiable when working on differentiation. Not to mention that if you have a growth mindset and believe that even though your students may differ in "their initial talents and aptitudes, interests, or temperaments" (Dweck, 2017, p. 16), all of them can accomplish any goal as far as they make an effort and are supported by their peers and teachers. Likewise, content, such as essential knowledge, understanding, and skills, will also be non-negotiable.

Thus, on the grounds of students' readiness, interest, and learning profile, teachers may differentiate the way students gain access to content, the process, and the product used to evaluate students' performance while taking care of providing an effective and safe environment that meets students' needs, through a variety of instruction strategies such as graphic organizers, scaffolded reading, front-loading vocabulary, small-group instruction, mode of expression options, learning contracts, learning or interest centres, independent inquiry, sidebar studies, jigsaw reading. (Adapted from Sousa and Tomlinson, 2018, p. 11)

The instruction strategies described by Sousa and Tomlinson (2018, p. 11) are especially useful when we consider transferring background knowledge and skills from one language to another. This means that if a student is a good reader in their first language (L1), they will probably be a good reader in L2, given that speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills are completely transferable from one language to another.

To help teachers plan the "when, why, and how" to create differentiated classes, Bondie and Zusho (2018) introduced a decision-making framework denominated ALL-ED (All Learners Learning Every Day) that is based on adjustments and sustainable class routines. They defend the premise that if teachers establish a classroom routine where students can work independently, they will have more time to focus, consider their students' learning processes and achievements, and work on necessary adjustments in real time.

An interesting feature in the ALL-ED differentiation strategy is that most of the job is done by students themselves, who are trained on a Self-Regulated Learning Routine that intersects OSCAR (Objectives, Starting Position, Criteria, Action Patterns, and Reflection), leaving the teacher the role of defining MUST HAVE and AMAZING criteria while scaffolding or helping resources are made available for independent use. (See Figure 2)

OSCAR

Objective

Starting position

Criteria

Action Pattern

SELF-REGULATED ROUTINE

Planning

Monitoring

Action Pattern Control

Return to Reflect Reflecting

Figure 2: OSCAR and Self-Regulated Routine. Bondie and Zusho (2018, p. 46)

Similar to ALL-ED, Heineke and McTighe (2018) state backwards design and differentiated instructions would establish a rigorous curriculum through high-quality instruction that would support the simultaneous acquisition of both language and content, as well as generate a more independent learner since it would work not only on content but especially on how the content is taught and learned.

Given the above, we may consider the use of Complex Instruction defined by Cohen and Lotan (1997) as "a pedagogical approach that enables teachers to teach at a high intellectual level in academically, linguistically, racially, ethnically, as well as socially heterogeneous classrooms" even if these students are not proficient in the language of instruction (p. 15). Throughout their texts, they discuss the class organization and the strategies used for organizing learning experiences, including group work design (Cohen and Lotan, 1997, 2014) that will also challenge and enhance advanced students. Following the same intention of Cohen and Lotan (1997, 2014), besides recommending the use of classroom routines, Bondie and Zusho also emphasize allowing students to work in small groups in which they are given a role, such as speaker, listener, recorder, reporter; differently, however, they affirm that the resource management must be done before or after group discussions.

Yet, although researchers such as Sousa and Tomlinson (2018) have also advocated the pitfalls of establishing a differentiated curriculum, especially when comparing a growth mindset teacher to a fixed mindset one, they consider using different material or leveled texts when texts' language seems to be in a frustration level to the student. In any way, most authors, including Heineke and McTighe (2018), do not recommend adapting the curriculum or the essential knowledge, understanding and skills, especially if it is watering down the curriculum or learning goals.

Relevant and useful differentiation strategies based on student's readiness

For this research to be conducted, a growth mindset was ideal, together with an attitude of eliciting effort and joining students in their journey, doing whatever it takes to guide them to success. Therefore, they "teach up," stretching students' abilities and encouraging the development of Bloom's Taxonomy's higher-order thinking skills while supporting and scaffolding activities for students with learning gaps. Hence, following Lotan's Complex Instruction groups, they use flexible groups formed by mixed-abilities students and provide students with "respectful tasks that are equally interesting, appealing, important and dependent on high levels of reasoning." (Sousa and Tomlinson, 2018, p. 32).

Thus, they identify OSCAR by backwards designing the curriculum objective, evaluation criteria, and learning experiences, applying diagnostic evaluations, and creating action patterns that include the activities that will be performed by students and selecting those that will need adjustments or scaffolds. In addition to these steps, they constantly reflect on class strategies and outcomes.

Furthermore, as presented by Cohen and Lotan (1997, 2014), based on the diagnostic evaluations, they use Complex Instruction to allow any student, whatever point of learning they are, to grow their knowledge, understanding, and skills through different stations and

active methodologies that provide them with learning experiences. At this point, teachers will choose a differentiation approach to adjust instructions using the thinking routine CARR Check (Clarify, Access, Rigour, and Relevance Check) within the learning community while keeping the same goals, resources, and assessments. Eventually, adjustments are made during classroom routines with an individual or a group of students based on the teacher's monitoring skills.

The teacher will use the CARR Check to adjust SHOp (Structures for Tasks, Help and Options) to monitor students' work. This monitoring could be done by posing questions to encourage higher-order thinking skills or answering students' doubts with thought-provoking questions.

An important point, when working with differentiated instructions, should be allowing all students to work on both Bloom's lower and higher-order skills at the same time, as Bloom's Taxonomy was developed for evaluation and not for teaching.

Therefore, if you work with groups, they should comprise students with mixed abilities and specific roles such as facilitator (the one who explains the task), materials manager (the one responsible for acquiring the necessary resources), group moderator (who is responsible for easing interpersonal conflicts and for being attentive to each member they must make sure everybody speaks and is listened to), timekeeper (responsible for making the group aware of the time they have), and reporter (responsible for reporting what the group have discussed to the whole class). It is crucial to mention that Complex Instruction strategies usually create individual and collective products, thus encouraging collaborative and cooperative learning.

Even though Differentiated Instruction seems to focus on the individual rather than on collective work, both ALL-ED and Complex Instruction approaches can work with students individually or divided into stations where they will work on different tasks so that they accomplish the same goal, meaning that in both approaches instructions and tasks, as well as the number of groups' members and the material they receive may vary. At the same time, the essential learning objective is maintained.

A feature that can be used with Complex Instruction and ALL-ED to differentiate is the "Menu" approach, introduced by McThighe (2021), according to which we keep the essential knowledge, understanding, and skills that will be developed by learners while giving them options to produce and deliver their final products. An example of this could be students reading and analysing novels to explain their stories, themes, or techniques to their peers using a variety of genres, such as podcasts, reviews, video reviews, articles, essays, comics, poetry, songs, or games. In addition, developing a brochure on nutrition or a healthy menu may have differentiated the students' familiarity with their audience or context, for instance.

Furthermore, the work by Sit (2017, p. 109, 110) highly advises us to make instructions explicit and clear so that students are aware of their learning goals and the knowledge and skills necessary to accomplish them. The instructions should also bring "powerful questions" that will activate students' critical thinking and facilitate their learning.

Another substantial strategy to work with differentiation is providing different supporting systems and tasks at different complexity levels to students who need scaffolding or previously required knowledge coverage and to have "anchor activities" available for the advanced or fast-finisher students. Moreover, when thinking of anchor activities, according to Sousa and Tomlinson (2018, adapted from p. 194), they should focus on essential knowledge, understanding, and skills that are worth students' time and effort and are sufficiently interesting to warrant students' attention, while not fluffy, punitive, or graded.

Furthermore, all students should be taught procedures to obtain help when the teacher is busy. Among these procedures, we could mention attentive listening to initial instructions, peer instruction, and having alternative materials to help scaffold learning or guide students in their tasks.

Considering the above within the present context, as English lessons usually work on reading and writing on a variety of themes, our essential knowledge is developing the skills to comprehend and write a variety of genres such as argumentative, narrative texts, poetry,

etc. In developing this, our task will be to include real experiences in which students will not only read a variety of texts and answer comprehension questions but also analyse the language used to appreciate discursive techniques in a way they can use when writing their texts.

Having said that, differentiating in an English as a Second Language Class includes exploring the genres' structures first with model analysis and then with supported and process writing in which diagnostic and formative writings precede the summative one and provide students with specific theme vocabulary, linking words and starting sentences, for example.

Reading should also be scaffolded and supported by informing the genre and asking students to read it for the first time just to learn what it is generally about so that they can work on skimming and scanning activities that will help them to get more concrete ideas from the text, before going to more abstract comprehension. Most of the time, an openended questionnaire that starts with superficial scanning questions will be a path to lead students to a deeper comprehension of the text.

Since the beginning of our research (May 2023), students have been exposed to a variety of genres such as advertisement and propaganda, articles and essays, news, and short stories. To make this possible, regardless of the genre being explored, students were always encouraged and guided to analyse their structure, the most common connectives used in the texts, as well as their language choices and discursive strategies to convey meaning.

This approach was selected to stimulate critical thinking, a Bloom's Taxonomy high-thinking order skill, in all our students. Therefore, while more advanced students were working on recognizing the use of repetition (for example, through the use of synonyms or paraphrasing, figures of speech, etc.), our less skilled students were not only guided to notice less abstract language and how the ideas were organized but also on some reading strategies that could help them to overcome every day reading challenges, while avoiding translation.(See Figure 3)

Global Reading Strategies (GLOB)

Allow readers to intentionally monitor or manage their reading

● Preview the text before reading

● Skim the length and organization of the text

● Scan to get specific

Problem Solving Strategies (PROB)

Help readers to directly solve reading difficulties

● Read slowly and adjust your reading speed to deal with difficult material

● Try to get back on track when losing

Support strategies (SUP)

Basic mechanisms to enhance reading comprehension

● Read aloud to understand the text

● Taking notes while reading to understand the text and make larger

information

● Decide what to read closely and what to ignore

● Use Background knowledge

● Use context clues

● Use tables, figures, pictures

● Think if the content fits the reading purpose

● Critically analyse and evaluate the information

● Pay close attention to bold or italic

concentration

● Guess the meaning of unknown words

● [Rely on cognate words]

● Use prefixes, suffixes, and roots to guess the meaning of words

● Stop occasionally to think about what you have read

● Picturing or visualizing the information to increase retention

connections

● Underline/highlight and circle information

● Paraphrase

● Go back and forth to find relationships among ideas

● Summarizing what you have read to reflect on important information and key points

● Discussing what you have read with others to solidify connections and understanding

● Make a mind map

● Use reference materials to identify terms or ideas that you do not initially understand

● Ask yourself questions you would like to have answered through your reading

● Think about information in both English and native language

Figure 3 - Adapted from Lien (2011) and Par (2020)

Additionally, the activities provided were built to make students more confident about their reading ability, so they went from less challenging to more challenging questions. Thus, firstly, students were guided through a shared read-through, during which they should orally discuss the texts' main ideas (GIST - General Information) in small mixed-ability groups. After that, they scanned the text to get specific information, such as dates, places, etc., so that they could work on the comprehension questions, language, and genre analysis.

They were also instructed to work independently (individually or in pairs) on reading a novel and crafting a reading log through different thinking routines. Working independently was a moment for the teacher to monitor their performance and consider how to adjust and ensure learning and the story's comprehension. During these moments, the students were also provided with supporting resources such as dictionaries or from their peers.

Following the theories cited in this review, our work with both groups has been structured as described below:

● Diagnostic Writing Activity: students were invited to write diagnostic texts to acknowledge their starting point in the genres (argumentative and narrative texts). To analyse their genre skills, they were allowed to write about any theme they found interesting or were passionate about.

● Instruction: all students took part in mini-lessons; moreover, students were provided with handouts on genre and vocabulary or prompts to help them with their production. Therefore, while more advanced students were able to work more freely without following prompts in the handouts, less fluent students made use of these and were able to build more standard texts. Working on news, for example, they had the leading questions to guide them in creating the lead paragraph. Then, they were stimulated to write at least two more paragraphs to include additional ideas or information.

● Ongoing assessment: students were monitored daily throughout their writing process, which meant they had the opportunity to receive support from the teacher. At the same time, writing and submitting a first draft for feedback on language, content, and structure so they could rewrite it before being marked. It is crucial to mention that the feedback did not solve language, content, or structure issues but pointed out what could be improved there with notes such as "SVA" (for Subject-verb agreement); or "Who are you recommending this book/film/game for?"; "Add the synopsis to your development."

Peer feedback was also frequently used during peer feedback activities; students were guided to read and evaluate the clarity of each other's work. Peer feedback was also a tool frequently used during the activities and in peer feedback activities; students were guided to read and evaluate the clarity of each other’s work.

In addition, when working on "research-based essays," for example, besides the steps mentioned above, students were guided on finding sources. Then, they divided their work into stating arguments, selecting evidence, paraphrasing evidence, and writing their essay. In addition, when working on “research-based essays” for example, besides the steps mentioned above, students were guided on finding sources and then had their work divided into stating arguments, selecting evidence, paraphrasing evidence and writing their essay.

● Differentiated feedback based on student readiness: even though the entire course was designed to generate growth opportunities for all students, each student received feedback on genre, content, cohesion, coherence, and language, such that they all had to work on an aspect of these criteria. More fluent writers, for example, were guided on using more advanced linking words and complex compound sentences.

● Final assessment: students submitted their final text version and were graded.

Working with differentiated instructions has not been easy, even though many resources, theories, and approaches are available. I had to make choices, and when doing that, I was afraid of setting low expectations for my students and impairing their development. Moreover, I faced colleagues and co-workers who stated I should have adapted the curriculum or the evaluation criteria because some students could not keep up with their peers.

Then, analysing all the scenarios and considering my students' learning objectives, I noticed they could work on communicative achievement in writing and reading. This enabled my students to read their texts using reading strategies with a glossary or a dictionary when they needed to address vocabulary. At the same time, I could organize questions that followed the same order as in the text. In this manner and with time, they would have experienced higher-order thinking skills, and eventually, they could explore the texts' language and discourse to build their understanding.

In addition, writing should be done by transferring their first language knowledge to English or by exploring the genre structure in open questions that allow them to use their language according to their English level. They would also have a model to follow and analyse their structure.

On this journey, however, I encountered some setbacks as some students' English was really at beginner level, and they became stuck when reading parts of the texts I chose. I was confident that they would be able to read if they used the reading strategies I had taught reading strategies to other classes. Nevertheless, some students became frustrated, especially when the text included figures of speech.

Eventually, after the hard work and frustration presented by some of my students, I came to agree with Sousa and Tomlinson (2018) when they stated that sometimes the texts have to be changed. Despite this, however, I have seen much improvement in various students and students for whom writing has become easier during the semester.

Considering the literature available, although I found many books on differentiation, many were published by the same authors. Furthermore, there is a lack of extensive work specialized in teaching a second language.

The Author

Daniela Gonçalves de Araújo Antoniazzi is an experienced, qualified English and Portuguese Teacher with a bachelor's degree and Teaching Credentials issued by Universidade de São Paulo (USP). She is a CELTA holder specializing in Instructional Design, English teaching, and Bilingualism.

References

Bondie, R., & Zusho, A. (2018). Differentiated instruction made practical: Engaging the Extremes through Classroom Routines. Routledge.

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014b). Designing groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom. Teachers College Press.

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014). Designing groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom. Teachers College Press.

Dweck, C. (2017). Mindset - Updated Edition: Changing The Way You think To Fulfil Your Potential. Hachette UK.

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Heinemann Educational Books.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English Language Learners: Bridges to Educational Equity: Connecting Academic Language Proficiency to Student Achievement. Corwin Press.

Heineke, A. J., & McTighe, J. (2018). Using understanding by design in the culturally and linguistically diverse classroom. ASCD.

Lien, Hsin-Yi. (2011). EFL Learners’ Reading Strategy Use in Relation to Reading Anxiety. Language Education in Asia. 2. 199-212. 10.5746/LEiA/11/V2/I2/A03/Lien.

Par, Leonardus. (2020) The Relationship between Reading Strategies and Reading Achievement of the EFL Students. International Journal of Instruction. V. 13, N. 2, p. 230. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1249084.pdf. Accessed on: 25/01/23.

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners. John Wiley & Sons.

Rubie‐Davies, C. M. (2009). Teacher expectations and perceptions of student attributes: Is there a relationship? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909x466334

Sit, H. W. (2017). Inclusive Teaching Strategies for Discipline-based English Studies: Enhancing Language Attainment and Classroom Interaction in a Multicultural Learning Environment. Springer.

Sousa, D. A., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2018). Differentiation and the brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-friendly Classroom.

Tomlinson, C. A., & McTighe, J. (2006). Integrating differentiated instruction & understanding by design: Connecting Content and Kids. ASCD.

Pablo Molina Byers

Abstract

This article delves into the transformative power of non-directive coaching for educators. It explores how coaching fosters pedagogical shifts and acts as a catalyst for meaningful transformations, nurturing a dynamic educational landscape where innovation, change, and growth thrive. I have accompanied educators through professional growth and have witnessed their empowerment to adapt teaching practices effectively. By documenting change throughout their coaching processes, distinct cases illuminate diverse experiences and outcomes. I would love for this article to share the profound impact of this approach, offering insights into a future where teaching excellence is nurtured through agency, collaborative inquiry, and action research.

"The only constant in life is change." - Heraclitus

Yes, quite a cliché sentence to use for an academic article opener. But it IS true. So, if change is constant, how do we know? How do we become aware of it? How often do we reflect, record, and document it in our professional journeys? How do we use those records (if at all) to encourage development and change? How do we actually do action research?

Well, this article looks to share how using a coaching approach for educators' professional development is so transformational in part because of how it encourages self-reflection and documents change.

The article will:

1. Outline the key principles of coaching that relate to action research,

2. Show what structure is followed to ensure reflection, planning, and action,

3. Share what tools are used to record change and progress,

4. Showcase the results found from two informal case studies.

These four elements construct a robust, observable, and documented picture from which we can draw conclusions and act upon regarding the different methods available for professional development (PD) in our industry. What is coaching for educators in the context of this article? How is it different from mentoring, training, and language coaching?

In favour of focus and clarity, a table is provided (see Appendix 1) where you can better observe the differences between coaching for educators and other approaches used for PD. The table aims to serve as a general guide and is non-exhaustive as it simply compares the main features of different approaches.

Definition of coaching for educators:

Coaching for educators is a collaborative, reflective process where a coach accompanies an educator to identify goals, develop strategies, and plans to implement changes that improve professional practices and, ultimately, the students' learning experience. It is a nonevaluative partnership emphasizing continuous professional growth through guided reflection and strategic action.

For this article, the term 'educator' will refer to the wide variety of roles within the sector. By educators, I refer to teachers, trainers, materials and course writers and designers, directors of studies, academic managers, directors, school owners, etc.

Key principles of coaching that relate to action research:

Firstly, if we understand the steps of action research to be:

1. Develop a plan of action.

2. Implement the plan, strategy, or activity.

3. Observe its effects.

4. Reflect on the effects and make changes accordingly.

Then, three key principles relate coaching to action research. These are that it is goaloriented, requires reflective practice, and is an ongoing process.

To maximise the effectiveness of any coaching process, it is imperative also to adhere to the principles that govern the profession and make it an ethical and standardised practice. Some of these principles are non-directiveness, agency of the educator, judgment-free active listening, trust, and confidentiality.

Back to how it relates to action research, coaching focuses on setting and achieving specific, measurable goals. These can often be related to improving classroom practices, student

engagement, and personal and professional soft skills such as connection, time management, communication, active listening, or emotional management. Because these goals are measurable, they are also recordable.

To identify and define their goal or ideal/wanted outcome (situation B), educators have to reflect on their current practices, situations, or classroom realities to have a clear vision of the starting point (situation A). Obviously then, reflective practice is central to coaching. Through evocative, open questions, educators reflect on their experiences, analyse their actions and results obtained, make informed observations, and "land" their learning. By this, I mean to become consciously aware of their new vision, perspective, knowledge, or realisation.

This is the beginning of our action research. We start by reflecting on the starting point and where we want to be instead. We observe the differences and develop a plan of action to implement.

With situations A and B clearly identified and defined, we can work on that action plan by including possible steps or mid-term goals that will get us from A to B.

Unlike one-time training sessions or courses, coaching is an ongoing process supporting sustained professional growth over time. However, being an ongoing process does not make it endless. Quite the contrary, every coaching process is time constrained. On average, substantial changes and effects take around three months to be implemented and visible, and educators normally experience between 4-8 sessions to get there.

This is partly achieved thanks to following a GROW structure.

The GROW structure (Goal, Reality, Options, Will) is a widely used coaching framework that helps educators set and achieve their goals through a structured conversation. It facilitates and encourages learning by making direct use of action research elements.

Initial or exploratory session: The objective of this first session is to produce a plan on how the educator is going to go from "Situation A" to "Situation B."

After this initial session, each following session starts with a revision of their action plan, what results it has brought, how it has gotten the educator closer to their goal (situation B), and what the next step they want to focus on that will get them even closer. This last projection of "what the next step is to continue forward," marks the beginning of the 'G stage'.

Goal: Based on the findings from the previous action plan and the observations taken from it, we now move on to clearly identifying and defining what the educator needs next to continue progressing. In this stage, we engage with the different stages of action research as we build on the observed effects of previous actions, learn from the observations, and reflect on the next actions needed. We are also gearing towards developing a new action plan to aid us in taking those actions.

Reality: Once the goal is clearly identified and defined, we explore the current reality around that new objective. Educators assess their current situation, identifying strengths, weaknesses, and obstacles. This step involves a candid discussion about what is happening right now. We can see how this stage engages with action research since reflecting on current needs is necessary to decide on the following action. This stage normally brings newfound awareness and perspectives to aid educators on their learning journey.

Options: Equipped with their new learning, educators integrate them into advancing towards their goal. They generate multiple pathways to success by brainstorming various strategies and solutions. Therefore, we are directly contributing to the stage prior to plan development by considering which option would advance progress the most.

Will: Finally, educators commit to specific actions to reach their goal. This crucial stage finds its highest success rate when the plans are as detailed as possible. This includes considerations such as setting timelines, identifying potential obstacles and resources needed, when, how often, till when, where, how, the all-important 'what for,' the level of commitment to this action plan, and how aligned this action plan is with the overall goal of the process. This stage relates to action research since it directly develops an action plan.

Between the end of this session and the following session, the educator will:

● Implement the plan, strategy, or activity.

● Observe its effects and results.

● Reflect on the effects/results and make changes accordingly.

All this information is collected at the beginning of the following session, coming full circle. Educators create a clear and detailed record of their development by systematically using the GROW structure and documenting the discussions and decisions made during sessions. This ongoing documentation helps them stay accountable, reflect on their progress, and make informed adjustments to their strategies. We will now explore the tools used to record and document said development.

3. Documenting change: capturing the transformational journey

As we saw before, a key aspect of effective coaching is focusing on measurable goals. This documentation serves as a tangible record of their journey, offering insights into their development, challenges, and achievements. Therefore, it is vital for reference regarding documenting change and acting on action research. Here are a few common tools used during and between sessions.

Standard tools to document change.

Session notes: Through active listening, the coach and educator can take notes during each session, capturing key points, reflections, and action plans. It is of vital importance that these notes use the same words the educator has produced and not the words the coach has interpreted. These notes serve as stepping stones, documenting the educator's progress and changes over time. Before the beginning of the following session, or when sitting down to act on their action plan, the starting point is often these notes taken from previous sessions.

For educators, hearing or reading their words is a powerful anchor to their process. You can find a sample copy in the resource pack attached at the end of the article in the "references" section.

Self-Reflection Forms: The most profound documentation method is the self-reflection form (Appendix 2) completed by educators after each coaching session. These forms prompt them to reflect on their learning, insights, and areas for growth, fostering metacognition and self-awareness.

Recordings: In addition to written notes, recordings of coaching sessions provide valuable insights into the dynamics of the coaching relationship and the nuances of educators' reflections. Recordings provide the valuable opportunity to observe yourself in a conversation from a different perspective as a third-party observer. This observational position can bring insight and allow educators to harness hindsight.

What is more, with Zoom's latest AI integration, you can get summaries of the topics and takeaways from each session, providing yet another method of recording the process. I personally facilitate these after educators have already completed their self-reflection forms so as not to influence their own conclusions. Please refer to the resource pack in the "references" section to access a sample session.

End-of-process Questionnaire: These are a collection of questions designed to encourage educators' reflections on the overall process, their goal, their changes, and the resources they have obtained. It stands as a final statement of their progress and ability to continue their learning journey on their own.

Learning journals or Logbooks: In addition to the above methods of documentation, which could be considered part of the system, learning journals or logbooks serve as invaluable tools for capturing the nuances of educators' development journey. In contrast to the previous methods, logbooks or learning journals are private. These personal reflections offer a space for educators to record their thoughts, insights, and epiphanies, providing an even richer, more in-depth awareness of their growth over time. This facilitates meaningful dialogue with their coach and can often bring about more efficient learning.

Specific coaching tools that also document change

Within a coaching session, there might be instances where the use of specific tools would benefit the educator. These tools directly engage with action research since they explore current situations and help devise future outcomes. Hence, they are vital initial stepping stones in developing actionable plans to promote and document change. Below I simply offer two examples widely used in many coaching practices.

Inspired by the "Wheel of Life," the "Wheel of the Educator" is a visual tool that helps educators evaluate different aspects of their professional lives. This wheel is divided into segments, each representing a key area of their role, which they have identified and chosen. Examples include classroom management, lesson planning, student engagement, professional development, work-life balance, communication, leadership, delegating, training, and team building. Educators can gain a holistic view of their current professional state by assessing their satisfaction and effectiveness in each area. Please refer to the resource pack in the "references" section to access a sample template.

Goal Setting: Based on their assessment, educators identify the area they want to improve and start designing specific goals for each area.

Action Plan: Educators develop an action plan to achieve their goals. This includes specific strategies, resources needed, and a timeline for implementation.

Regular Reviews: Periodic reviews of the wheel allow educators to track their progress, reflect on their experiences, and adjust their action plans as necessary.

By documenting their ratings, goals, and reflections, educators can create a detailed record of their professional growth. This visual and structured approach makes identifying patterns, addressing challenges, measuring progress, and celebrating successes easier.

The climber

"The Climber" is a visualisation technique that encourages educators to project their future selves or situations, fostering a forward-thinking mindset and motivating continuous improvement. This method involves guided visualisation exercises where educators imagine themselves overcoming challenges and achieving their professional goals. It primes educators to start with the end in mind, facilitating possible steps to take in an actionable plan.

Future Projection: Educators visualise a specific future scenario, such as successfully implementing a new teaching strategy or achieving a balanced work-life routine. They focus on the feelings, behaviours, and outcomes associated with these achievements.

Reflection and Planning: After the visualisation, educators reflect on their experience and identify the steps needed to reach their envisioned future. This includes setting short-term and long-term goals.

Documentation: Educators document their visualisations, reflections, and action plans. This record serves as a motivational tool and a tangible reminder of their aspirations and the path they need to follow.

A personal favourite is the use of pictures. Encouraging educators to draw a picture of their future enables them to anchor the image visually, which functions as a reminder and source of motivation. You can access a sample audio and picture in the resource pack in the "references" section. This last technique was adapted and implemented in the following case study.

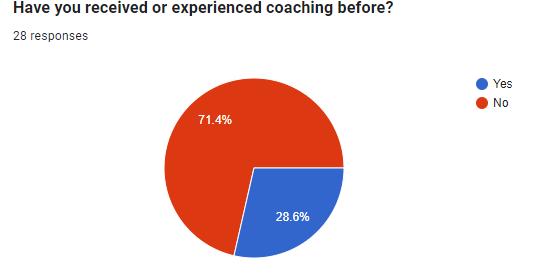

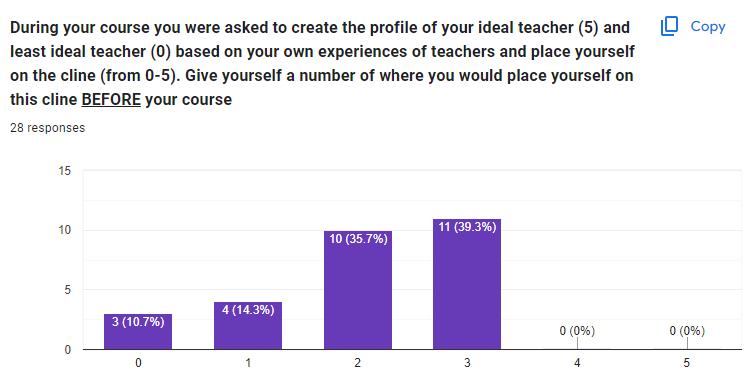

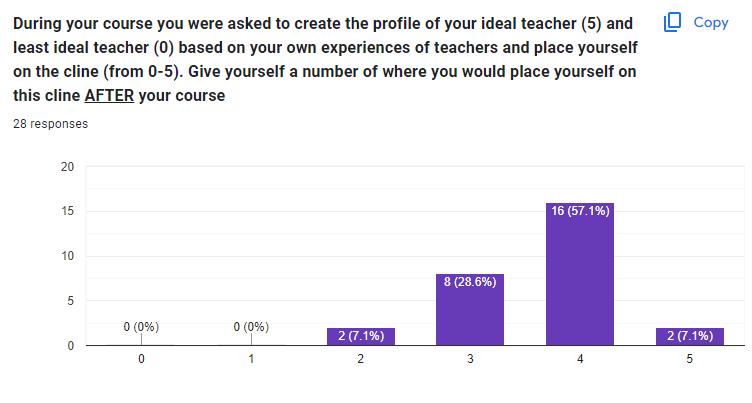

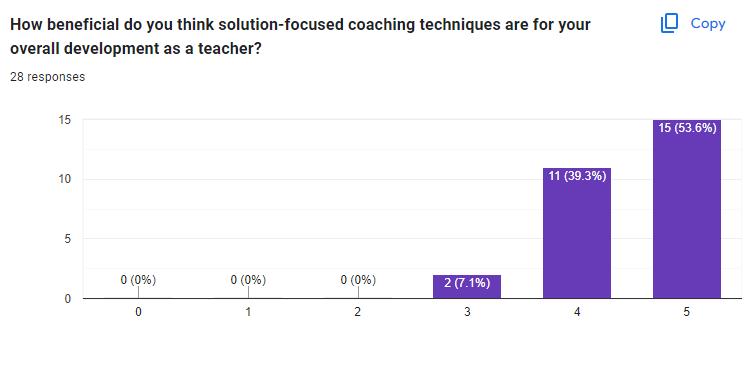

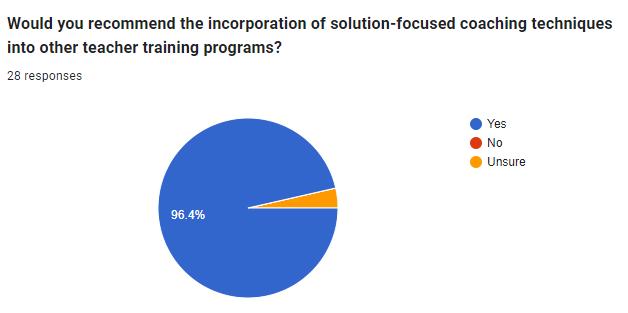

In collaboration with Paul Ashe, we have tested the effects and benefits of using coaching techniques in teacher training contexts. Trainee teachers enrolled in their CELTA courses were asked to envision their 'ideal teacher' at the beginning of the course and to write down the following information:

● how that teacher behaves,

● what their voice is like,

● what their body language looks like,

● how they dress,

● how students react to them,

● how they move around the room,

● how they plan,

● what their strengths are,

● what their main characteristics are.

Then, throughout the course, trainers repeatedly referred trainee teachers to their 'ideal teacher' to check their progress. The data obtained from the questions in Appendix 3 demonstrates the positive impact this isolated coaching technique has had on the development of teachers. Further in its favour, it highlights how in line coaching and action research are since this visualisation tool has helped educators design plans, carry them out, observe their effects, and re-evaluate accordingly in favour of professional development.

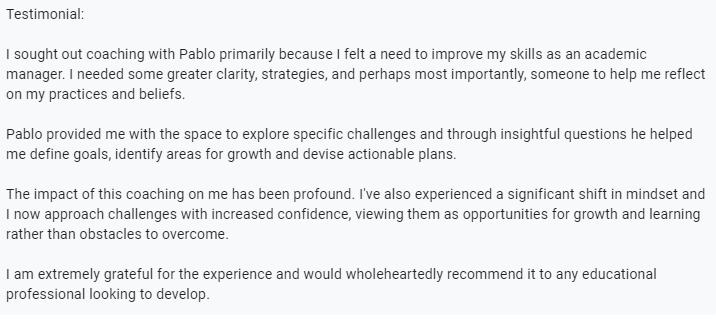

In another endeavour of action research, I have accompanied educational professionals in their personal and professional development through coaching processes. The distinction with the previous case study is that these professionals have experienced coaching in a fuller sense as opposed to the isolated use of a coaching tool like "The Climber."

In Appendix 4, we can read the personal testimony of Lisa Dold, Head of Training at ACEIA (Andalusian Association of Language Centres).

For a summary of other professionals' changes, please refer to Appendix 5.

For a fuller account of the experience these educators have had through coaching, you can access some of the feedback they provided. Please refer to the resource pack in the "references" section.

The personal reflections collected, along with the data from the previous case study, showcase the profound transformational power of coaching as a PD approach and how the action-research nature of the process makes change and development so much more impactful and long-lasting.

Having analysed how coaching integrates action research and reflection, the framework it follows, the tools used to document change, and especially these two case studies, it is apparent that it has positively impacted the PD of the educators who have experienced it.

Whether through isolated coaching techniques or comprehensive coaching processes, educators reported significant improvements in their professional practices. Arguably, they reported even more change in their personal growth.

The integration of coaching into educators' professional development proves then to be a powerful approach, partly due to its inherent action research nature and the essential element of reflection. The iterative cycle of planning, implementing, observing, and reflecting fosters continuous improvement and ensures that changes are relevant, effective, and sustainable.

Another factor contributing to the transformative power of coaching could be inferred to be the documentation and sharing of the process, which allow for objective accountability. Interestingly, some of the research on accountability has found that:

Having an idea or goal: 10% likely to complete the goal

Consciously deciding that you will do it: 25%

· Deciding when you will do it: 40%

Planning how to do it: 50%

Committing to someone that you will do it: 65%

· Having a specific accountability appointment with someone you have committed to: 95%

(Adapted from - https://www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/the-standard/2018-3/the-power-of-accountability/ )

Overall and conclusively, there is a positive case for using coaching for PD. To me, the most significant benefit of coaching in educators' development is its impact on students' learning experiences. When educators improve their practices and grow professionally and personally safeguarding their personal fulfillment and well-being, our students benefit from a higher quality of education.

Furthermore, it could be argued that by integrating coaching (and therefore action research and reflection) into educational institutions, we could foster cultures and communities of dynamic and supported continuous improvement, empowering individuals at all levels. This would help us better navigate the complexities of our societal roles, lead with integrity, and ultimately live more connected with ourselves and others.

Then, if we know "The only constant is change," perhaps we could take the opportunity to envision teacher development and education from a different light and adapt to our educators' needs so that they are as best prepared as possible to help their learners, who are our future. What change would that bring about in the world? And how would we document it?

The Author

My name is Pablo Molina Byers, founder of Generación Futura, where I accompany educators and educational institutions to manage and achieve change and progress through coaching, mentoring, and training. My mission is for the educators of today to inspire, transcend, and enjoy for the benefit of our future generations.

References

Collaborator: Paul Ashe - https://www.linkedin.com/in/paul-ashe/?locale=es_ES

Collaborator: Lisa Dold - ACEIA - https://aceia.es/aceia-en-cifras/

Accountability facts: https://www.afcpe.org/news-and-publications/the-standard/2018-3/thepower-of-accountability/

Resource pack with tools and materials referred to in the article - (You'll have to provide feedback and basic contact details): https://forms.gle/eXcnLMdNnsRcJBer8

Appendix (1):

Approach Coaching

Objective

Improve teaching practices and professional growth

Focus Specific professional goals and reflective practice

Relationship

Collaborative, nondirective, goaloriented

Duration Can be short-term or long-term, depending on goals

Approach Non-directive, facilitates selfdiscovery and strategic action

Interaction

Two-way communication, reflective practice

Evaluation Non-evaluative, supportive and developmental

Outcome

Improved teaching practices, professional growth, positive student outcomes

Mentoring

Career development and general professional guidance

Broad professional and career guidance

Directive, experienced mentor guiding less experienced mentee

Typically long-term

Training

Impart specific skills or knowledge

Skill acquisition and knowledge transfer

Trainer-led, often one-way communication

Language Coaching

Enhance language proficiency

Mixed, sharing knowledge and experiences

Mentor provides advice and guidance

Often short-term, based on course or program duration

Directive, instructive and structured

Language-specific content and skills

Combination of directive and nondirective approaches

Varies, based on language proficiency goals

Mix of directive feedback and nondirective facilitation

One-way communication from trainer to participants

Non-evaluative, supportive

General career development and professional advice

Evaluative, may involve assessments

Acquisition of specific skills or knowledge

Interactive, involving practical exercises and feedback

May include assessments of language proficiency

Improved language skills and proficiency

Coach: Pablo Molina Byers

Educator:

Session #:

1. Session Summary

2. What have you learnt from this session?

Session Date:

3. Where and how can you apply what you've learnt?

4. How does this relate to your objective(s)?

5. What do you feel this session has missed?

6. What goal(s) have you set for yourself?

7. What is your action plan before the next session?

Appendix (3):

Appendix (4):

Question: What significant changes have you undergone since the start of the process? How important have these changes been for you?

Freeing myself from issues that worried me and hindered achieving some objectives and moving forward. Through this process, I have learnt to focus on situations differently and enjoy better experiences and more satisfactory results with my group of students

There have been several: I feel a change in my motivation towards my conversations, now viewing them as opportunities for growth and learning. This has definitely grown as a result of the process. Focusing on it felt like I was giving it the time, space, and importance to develop it, and this motivated me. I feel more aware of my thinking processes and what helps me think more clearly, as well as the specificity I need to apply to my goal-setting. This change has also been really important as I have been talking through things more frequently, having realised that this helps me think more clearly.

I have changed on an organisational level and on a personal level. It has helped me realise that not everything is black or white and that there are other ways to solve things.

The changes have been quite significant, especially when it comes to reflection and selfanalysis. Everything I have learnt during the process has changed me enormously. Now I feel that I can face any everyday situation with much greater confidence.

Above all, I have more peace, tranquillity, and happiness. I have managed to reduce levels of stress and anxiety. Another change has been loving and respecting myself, especially at work, which has been equally important during my process as it weighed heavily on me and I have been able to free myself.

I would highlight my willpower and confidence to achieve the set goal as significant changes, both of which have been further strengthened. These changes are very important to me on a personal level because they give me greater empowerment when it comes to carrying out other goals in my life.

My relationship with my surroundings and my people is easier and more fluid. These changes have been quite important as I get angry less often

Richard Cowen

Abstract

This article will focus on how mentoring enables one to support the future development of the mentee. Having passed initial qualification, such as CELTA, the mentee then often finds him/herself in a job with the minimum preparation time to succeed in the demanding EFL classroom. The support given by the mentor can actually make or break the new or inexperienced teacher, so the mentor role is vital. This action research will follow the mentoring of several relatively inexperienced teachers at the British Council in Poland and record how the mentoring programme impacted the teachers concerned.

Introduction

The term ‘mentoring’ is used in many different contexts, but to establish a definition in the context of teacher education, we may say that ‘mentoring is typically described as a process to help develop teaching practices, involving a nurturing relationship between a less experienced and a more experienced person, who guides a role model and adviser.’ (Bigelow, 2002; Haney 1997). This definition would seem to encapsulate the essence of mentoring in teacher education and is readily applicable to the context of this research study. The mentor/mentee relationship is by definition reciprocal and collaborative in that whilst the mentor provides support, feedback, information, and models appropriate practice to the mentee, the latter in turn, engages in a dialogic process by maintaining a flow of information to the mentor in terms of their professional and personal development and concerns as they embark on their initial or early teaching career. As such the mentor/mentee relationship can be likened to a ‘master’ / ‘apprentice’ relationship although it should be mentioned that the mentee can provide an impetus for the mentor to also develop as a more rounded professional. For example, ‘mentoring’ can be seen as an essential tool of CPD (Continued Professional Development), as the mentor might well be motivated in his/her role to expand their perspectives within the profession away from the bread-and-butter work of teaching in the classroom.

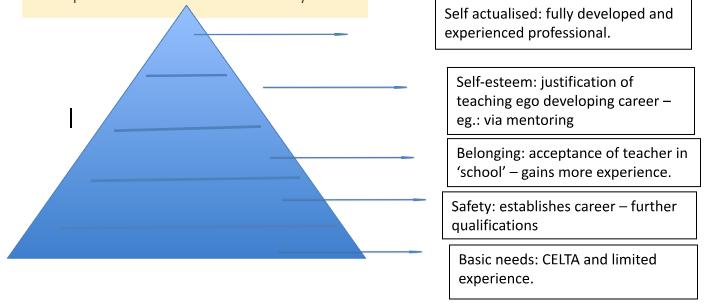

The mentoring paradigm might be analogous to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In order to conceptualise this, we can look at three hierarchies, including Maslow’s original hierarchy:

Maslow’s original Hierarchy of Needs

A conceptualisation of a teacher’s Hierarchy of Needs:

It can be observed that as far as the mentoring process is concerned, it is the second stage towards the base of the pyramid which is vitally important for the mentee. Having gained initial qualification through CELTA or an equivalent, the mentee then pursues his/her career as a TEFL teacher. Crucially however, the success or otherwise of this initial teaching experience is dependent upon the second stage (Safety and security). This is true not only for the mentee, but also for the other stakeholders in the institution – such as students, directors of studies, senior teachers, school directors, and others. If successfully negotiated, all stakeholders stand to benefit – but for our purposes, most essentially the ‘new’ teacher.

This is the point at which the mentor comes to prominence. The mentee’s need for support, advice, and a psychological sense of security can potentially be met by the mentor. Regarding the mentor, s/he is likely to be motivated in the role of ‘mentor’ by a desire to achieve a higher position on the teacher’s hierarchy of needs to the stages of ‘self-esteem’ and ‘selfactualisation’. At these stages, the mentor has acquired extensive experience in the classroom and has probably furthered his/ her qualifications – for instance, through DELTA and/or a postgraduate degree. Assuming that the mentor is motivated to develop further, it is plausible that he/she will adopt an approach in which the sharing of acquired knowledge will appeal as it will help to justify his/her raison d’etre in the profession.

The research was carried out at the British Council in Warsaw, Poland, and featured teachers early in their teaching careers. The British Council in Poland utilises a foundation entry system in which newly qualified teachers or teachers with limited experience can join the organisation on the proviso that they commit to a professional development programme. This programme comprises an induction programme, an in-house teaching course ‘Teaching Support Programme’ (TSP), and a mentoring system that aims to support and integrate these new teachers into the teaching style of the British Council. Within Poland (British Council has teaching centres in Warsaw, Krakow, and Wroclaw) there are five foundation entry teachers this academic year. Mentoring is seen as an essential part of the foundation programme.

One of the mentees is Dutch and has completed his Master studies in The Netherlands. The second mentee is a British native and has recently completed his CELTA. He started working at the British Council in January of this year. The other mentees are non-native teachers, two from Poland and one from Ukraine. Two of these teachers worked as learning assistants at the British Council before becoming teachers. They have all completed master’s studies and most have completed CELTA. These teachers work with a variety of age groups and levels, but most are either Primary (5–11-year-olds) or Secondary teachers (12-17 year olds). Master’s studies and most have completed CELTA. These teachers work with a variety of age groups and levels, but most are either Primary (5–11-year-olds) or Secondary teachers (12-17 year olds).

As a mentor at the British Council in Warsaw, over the last few years, I have been interested in analysing how effective the mentoring has been. Anecdotal evidence suggested that for the mentees, mentoring was indeed effective, but I wanted to gain a deeper insight into how the mentoring process impacted the mentees and so I decided to carry out a survey and interview my mentees.

Developing an improvement plan (see Appendix 2)

A foundation entry-level teacher will typically be observed very early on in the academic year and a mentor – appointed by the teaching centre management – is made fully aware of the feedback the teacher received. Based on feedback from the original observer, the mentor then arranges an initial meeting with the mentee, and a development plan is drawn up. Whilst feedback from the initial observation is obviously important, it is not the only determinant of the plan. During the initial discussion, other perceived areas for development are also integrated into the plan. It should be emphasised that the development plan is a dynamic document and changes as perceived needs emerge. For instance, subsequent observations might uncover other developmental needs or in discussions between the mentor and mentee, other needs might emerge which need addressing. The development plan is therefore a ‘live’ document that is subject to the emerging needs of the mentee.

Parallel to the mentoring plan, the mentee also follows a TSP (Teaching Support Programme) in which s/he follows a British Council course covering the basic areas of effective classroom teaching (lesson planning, classroom management, etc). The mentee is observed several times during the academic year with the observation focused on each of these basic areas. The observation is either carried out by the mentor or alternatively, an academic manager

and the feedback from these observations contributes to updating the mentee’s development plan.

Aside from the ‘academic’ aspects of the Plan, pastoral care is also part of the development plan. For instance, it might be that a personal issue is having a negative effect on classroom performance so the mentor encourages a relationship in which the mentee can feel comfortable discussing personal issues – perhaps, for example, the mentee is having some settling in problems in what is likely to be a new environment.

As mentioned above, the plan for the mentee derives from a combination of areas which have been flagged for development from his/her observation feedback, the TSP programme, the Learning and Development Plan, and from discussion and consultations between the mentee and the mentor. The plan is then implemented over the academic year and discussed weekly with the mentee to check progress. The plan is dynamic and further areas for development are added and implemented accordingly. Additionally, personal and pastoral care is included in the plan so as a more holistic approach is provided for. Weekly meetings between mentor and mentee give each party an opportunity to update the other regarding the effective implementation of the plan.

In implementing the plan, the mentor is in contact with a senior teacher and sends the latter a weekly update of the meeting with the mentor. The senior teacher will also update the mentor with details of any observations or other developments regarding the mentee. Hence, there is a constant interaction in progress as illustrated below:

Observations

TSP

Senior Teacher& MGMT

Pastoral needs

INSETTs

LDP

From all perspectives – mentee, mentor, senior teachers, and management, and ultimately students – it seems the mentoring plan worked well and yielded mutual benefits for all concerned.

The mentee is the greatest beneficiary because s/he is placed at the centre of the plan. Without a mentoring process the mentee might well find the need to integrate into the organisation jarring and challenging. The mentoring plan is in place to help the new teacher manage this integration. Evidence from the survey and anecdotal feedback suggests that the mentoring process and development plan do help the mentee settle into their new working environment (see below). As regards the mentor, the Plan enables the mentor to organise in an efficient way the process of the teacher’s integration into a new working environment.

The holistic layout of the plan means that potential problems and issues can be anticipated and accommodated into the plan. Thus, the mentor has a tool which is instrumental in smoothing the process and establishing meaningful criteria for the successful integration of the teacher. The organisation (in this instance, the British Council) needs to ensure that newly recruited teachers settle in as smoothly and quickly as possible so as they (the teacher) are ready to execute teaching duties to as high a standard as possible.

Reflection on the effects of the plan

The survey was carried out on MS Forms (see Appendix 1). In total, I asked 13 open questions, aiming for more qualitative rather than quantitative feedback. As there were relatively few mentees in this case study, I thought that this was a good opportunity to undertake deeper research through a qualitative approach. I then interviewed the mentees to further substantiate their responses from the survey to gain greater insight into their responses.

The findings of the survey were overwhelmingly positive. Virtually all of the teachers had a first degree and had completed CELTA before commencing work at the British Council. Expectations of mentoring (Q2) included: ‘someone experienced in the field who would be prepared to help a less experienced teacher’, to ‘someone to help me create interesting lessons’, and ‘someone who will guide and advise me whenever required.’ The reality of being mentored (Q3) included one comment in which the mentoring ‘was not as intimidating as expected’ to ‘just as expected’. One mentee added: ‘there was lots of emotional and mental support, so I felt comfortable about “being myself.” For Q5, mentees found that expectations had been met, even exceeded. For Q6, mentees found that the practical help and advice given ‘was irreplaceable’ and that ‘I had a terrific rapport with my mentor.’ Likewise, for Q7, mentees unanimously commented that mentoring had had a positive impact on their teaching, especially for those mentees who were faced with teaching either YL or early years. Help and advice with classroom management issues were to the fore here. Regarding Q10, again all the mentees agreed that the mentoring process had helped them feel more settled in their relatively new environment. Q11 – improvements to the mentoring process included a request for ‘group mentoring sessions’ to work alongside individual mentoring – something which we will consider in next year’s mentoring programme.