As the vibrant hues of autumn signal the beginning of a new academic year, we find ourselves at the threshold of yet another exciting chapter in the ESOL SIG and ESOL education journey. This new academic year promises to be a period of transformation and growth for the SIG and each of our dedicated members. The world of education is constantly evolving, and so are the methods and tools at our disposal. With this in mind, we have curated a range of activities that cater to the changing needs of our students and educators alike.

Two ESOL SIG committee members, Larysa Agbaso and Roshii Jolly, have been incredibly busy organising Interactive webinars for the forthcoming academic year over the summer months. In our commitment to foster continuous learning, we have scheduled a series of interactive webinars. From innovative teaching techniques and storytelling in the classroom to insights into the latest trends in language acquisition, these webinars will provide a platform for us to learn, share, and collaborate. Please look at our website and social media platforms for more information regarding these webinars.

As a SIG, we believe in the power of collaboration, engaging in collaborative projects with fellow educators and students across geographical boundaries. These projects will enrich teaching experiences and allow students to interact with diverse perspectives. Mark your calendars for the ESOL SIG’s first annual online conference, in conjunction with the Language Technology SIG (LTSIG) and the University of Nicosia – on 25th November 2023. Two plenary speakers have been confirmed, including Nik Peachy. Nik is a renowned writer, teacher trainer and consultant specialising in digital publishing, online course development and developing digital resources for teachers. This event will bring together ESOL/LT educators from around the globe, who will engage in thought-provoking discussions and connect with peers who share a passion for nurturing language and technology skills.

The ESOL/SIG committee members are already beginning to organise next year’s IATEFL conference 2023, which will take place in Brighton. We look forward to seeing you all there next year!

As we embark on this journey together, we encourage you to actively participate in these activities, contribute your ideas, and inspire one another. Let this academic year be a testament to our dedication to providing the best possible education to learners of English, no matter where they come from. Thank you for being an integral part of our SIG. Together, we will navigate the waters of change, embrace innovation, and continue to make a lasting impact on the lives of our students.

Here’s to an academic year of growth, learning, and shared success!

Warm regards,

Declan and Vivi Joint Coordinators: IATEFL ESOLSIG

Declan and Vivi Joint Coordinators: IATEFL ESOLSIG

Welcome to another issue of ESOL Matters! I hope this issue finds you well and looking forward to a new teaching term. You might notice that Declan, one of our editors, is now a Joint Coordinator of the ESOLSIG so I would like to express my thanks to him for all his help over the past year with ESOL Matters. Another change we have had is the inclusion of a couple of new committee members who joined us just before the conference in Harrogate, and you can get to know them a bit better in the first article of this issue.

Moving on to the main articles, Carol Goodey shares a community based project in Scotland, where local people and ESOL learners are encouraged to work together. Carol’s webinar on this topic is still available on our website, so do take a look for more ideas. The interactions between our learners and their neighbours continues as a theme in an article from Zuzanna Stein. Zuzanna teaches English to school children in Poland and her reflexive piece on the introduction of Ukrainian refugees is both timely and thought-provoking. We then have an article from Juana Simpson in Northern Ireland, which outlines how she utilised storytelling to promote inclusion in the ESOL classroom, another theme that runs through all three articles in this section.

In the research articles, we have a report from Rebecca Kay and Francesca Stella who set-out the ESOL landscape in Scotland. This research project was conducted during a time of great change for ESOL in Scotland and you may see similarities to your own teaching context if you are based in a different country. Julie Watson, on the Isle of Wight, shares her research into the language learning motivation of forced migrants, where their hopes and fears for the future are explored in her interviews.

In the article from Sean Duffield, the themes of inclusion and learner-centred approaches reappear as they are central to his research into textbooks utilised in ESOL classes in England. The mismatch of coursebooks and real world English is perhaps relevant for all teachers around the world and Sean raises some valuable points for reflection.

Finally, we have the views from the classroom, where Chloe Jacobs shares her Dogme lesson which was, of course, absent of coursebooks and utilised language elicited directly from the learners. We also have a report from two volunteers, Sandip Samra and Amelia Potts, who have been delivering ESOL classes in a rural area where asylum seekers have been placed in a hotel.

I hope you enjoy reading all the articles and if you would like to write for the next issue, please take a look at the website for more information. The next submission deadline is 30th December and it’s always great to hear from firsttime writers as well as seasoned researchers.

Happy reading!

Kathryn

Earlier this year, Sundeep and Maria joined the ESOLSIG committee. In this section, you can learn more about them and their connections to ESOL. We hope you will join us in welcoming them to the team and hopefully you will meet them at one of our events soon.

Name Maria MatheasWhat’s your ESOL background/connection to ESOL?

My first English language teaching job, right after completing the CELTA, was as an ESOL teacher in London. It was an outreach teaching role, which saw me travelling from one community centre to another across London’s East End, from Bethnal Green to Barking. This role exposed me to the world of working with migrants and refugees, and I immediately fell in love with it. This was back in 2001.

I then worked as an ESOL teacher for various FE colleges in London until 2013, and in 2014 I left the UK and lived and worked in France, Morocco and Thailand. On returning to Australia (where I’m originally from) in 2018, I was disheartened to learn that my UK ESOL experience and qualifications were not recognised for EAL teaching (English as an Additional Language, as ESOL is referred to here). In Australia, teaching migrants, refugees and asylum seekers is a highly regulated industry, and to be able to work as an EAL teacher, I need to complete a post-graduate qualification with a 22-day teaching placement. This led me to where I am now, juggling this pursuit alongside my full-time job (unrelated to ELT).

I am currently working towards a Master of TESOL, and my teaching placement is at a neighbourhood house (community centre), a nostalgic reminder of my very first job as an outreach ESOL teacher in East London. The students I have encountered here are as warm and generous as my ESOL students back in the UK, making this journey all the more meaningful.

What’s your role on the committee and what do you hope to achieve/what are you most excited about?

I’m the ESOL SIG's new Social Media Manager. My main hope is to foster a community of ESOL/EAL/ ESL teachers through our social media channels - a supportive space where we all feel comfortable sharing experiences, exchanging resources and providing support to each other.

What do you think are the biggest challenges facing ESOL teachers and learners at the moment?

In Australia, funding for EAL is based on outcomes, which puts pressure on providers to subject students to assessments that, often, they’re insufficiently prepared for. This can be very stressful for students and can even hinder their acquisition of the essential survival language skills that they actually need.

Why are you passionate about ESOL?

I’ve worked in jobs where I’ve had the distinct feeling that my efforts are having absolutely zero impact –this is the exact opposite of how I feel when I’m with my ESOL/EAL students. Teaching ESOL is the most meaningful and rewarding job I’ve ever had. I love being able to help people settle in their new countries, making them feel comfortable and at home. The feeling that I’m making a difference to people’s lives gives me a strong sense of purpose. Plus, ESOL students are the loveliest people you could ever hope to

Sundeep Dhillon

What’s your ESOL background/connection to ESOL?

I started teaching ESOL after completing my undergraduate studies and worked on an hourly paid basis at a further education college. This led to further teaching hours and eventually a permanent post. I’ve since worked in several further education colleges in the Midlands area of the UK as an ESOL lecturer, team leader, examiner and mentored PGCE candidates from local universities. Most of my earlier teaching was with adults, more recently I’ve taught 16-19 year olds and incorporated ESOL with other subjects including Business, Public Services and Travel and Tourism. ESOL is an area where the demand for provision has always been high and the funding precarious. Throughout it all, the students I’ve taught have always been eager to learn, committed and willing to share their interesting life stories and food!

What’s your role on the committee and what do you hope to achieve/what are you most excited about?

I am the Website Coordinator and hope to showcase the amazing work ESOL teachers do around the globe on the IATEFL ESOLSIG website. I am most excited about supporting teachers through providing updated information on ESOL contexts, practical classroom activities and professional development opportunities.

What do you think are the biggest challenges facing ESOL teachers and learners at the moment?

ESOL teachers often face having multiple levels of learners within classes which are oversubscribed and under-resourced. ESOL learners face the challenges of gaining access to regular ESOL provision while also navigating their daily lives using English.

Why are you passionate about ESOL?

The learners I have worked with always bring their full energy and attention to their English class despite having a wide range of issues and challenges to cope with. Providing the opportunity for people to learn and progress in their everyday life, studies and employment is something that I feel passionate about.

Copyright Notice

Copyright for whole issue IATEFL 2023. IATEFL retains the right to reproduce part or all of this publication in other publications, including retail and online editions as well as on our websites. Contributions to this publication remain the intellectual property of the authors. Any requests to reproduce a particular article should be sent to the relevant contributor and not IATEFL.

Articles which have first appeared in IATEFL publications must acknowledge the IATEFL publication as the original source of the article if reprinted elsewhere.

Published by IATEFL, 2-3 The Foundry, Seager Road, Faversham, ME13 7FD, UK. www.iatefl.org

Disclaimer

Views expressed in this newsletter IATEFL ESOLSIG ESOL Matters NEWSLETTER are not necessarily those of the editor of the IATEFL ESOLSIG of IATEFL or its staff or trustees.

ESOL classes and groups are invaluable, not only for people to learn English but also for accessing support and friendship from fellow students and ESOL tutors. ESOL learners come to class to improve their English but the ultimate goal is often to become more part of their new communities – to make friends, to get good jobs, to feel useful and to contribute in meaningful ways. Language skills can make this goal more attainable. These skills are often not sufficient, however, since the language barrier is not the only obstacle to integration. In this article, I move away from a focus on language development to consider an intercultural approach to integration and ESOL and reflect on the important role ESOL practitioners can play beyond the classroom.

Integration is a contentious term, with different ways to understand it. It can be understood as assimilation where newcomers are expected to adopt the language, customs and values of their new countries. Difference is seen as being disruptive so the aim is to reduce differences so that everyone speaks the one language, does the same things and holds the same values. Alternatively, integration can be understood as multiculturalism where differences between groups are recognised and valued. This is more positive but can lead to friction between groups if one group feels another is getting preferential treatment. Increasingly in policy, we see integration discussed as a two-way process, recognising the need for adaptation by both arriving and receiving communities. Building on this idea, integration can be seen as ‘a multilateral, multimodal, intercultural and dynamic process…as a restorative process that takes place in local communities’ (Phipps, Aldegheri & Fisher, 2022, p.22). This understanding of integration as an intercultural process recognises its complex nature and encourages us to take a wider view of the processes involved. It is not simply a matter of people improving their English since, even with good language skills, barriers to integration remain.

In the UK, for example, a hostile environment promoted by government policy along with a climate of fear created by the negative and incomplete portrayal of migrants in the media ‘spreads suspicion and unease throughout society’ (Forkert et al., 2020, p. 151). People from the local communities who have not had much contact with speakers of other languages can be wary and nervous of interacting with those coming to live in their area. They worry about the possibility of communication difficulties and about the differences they perceive.

ESOL learners have told me that although Scottish people are very friendly they do not tend to welcome others into their friendship groups. Researchers have heard similar things from people in Scotland and Ireland. Despite the friendliness of local people, there is very little social mixing between groups (de Lima & Wright, 2009; Ćatibušić, Gallagher & Karazi, 2021) and, when it comes to accessing employment, it also seems that improving language proficiency, while important, is not enough (Chick & Hannagan Lewis, 2020).

When people step out of ESOL bubbles to access services, employment or the wider community, it often does not matter how good their English is or how skilled they are, the barriers remain because they are often the only ones who have learned and adapted. As a result, we, as ESOL practitioners, need to shift the focus a bit and look beyond what we can do in our ESOL groups and classrooms, whether that be language development or pastoral support, and work to facilitate connections and learning in the wider communities, taking an intercultural approach.

The independent report on the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (Phipps et al., 2020) highlights the need for a more holistic approach to ESOL. The authors recognise that newcomers will need to adjust culturally to their new environment but argue equally that ‘receiving communities need to broaden their perspectives to ensure that ESOL is not seen as a technical fix to a “language problem” or “language barrier” but rather is framed within an intercultural approach’ (Phipps et al., 2020, p. 60).

The report touches on the inadequacy of training programmes such as the CELTA, often required to work or volunteer in ESOL, and highlights the need for training to be able to deliver ESOL more holistically where ‘ESOL is not solely about language acquisition, but also about supporting integration in a wider sense’ (Phipps et al., 2020, p.59). One local authority worker is quoted as saying, ‘staff do not come out of CELTA with the skills they need to work in communities...I always say every time I’d much rather have a community worker, I’ll teach them how to teach ESOL’ (p.59).

It is true that the work ESOL practitioners need to do is often not the work we were trained for. But for many ESOL practitioners, the skills needed to work in communities have been learned informally. Through our own interactions with speakers of other languages and our experience of facilitating learning, we have developed the skills and the knowledge to approach ESOL more holistically and interculturally and to work alongside other teams and organisations, to bring people together to learn from, with and about each other, and to foster integration.

In an ESOL SIG webinar earlier this year, I talked about some of the activities that we organised as part of a local Cultural Connections project, in collaboration with non-ESOL colleagues. These included a ceilidh, a world food night, a singing workshop, a beetle drive, a weekly community café, as well as walks and photography workshops. There is not enough space here to provide more details but the video is available to members on the IATEFL site. There, I outlined how we facilitated interaction and connection during the events, in English and in other languages, how we worked across teams, organisations and communities, and what people learned informally from participation – both ESOL learners and people from the local communities.

Working with non-ESOL colleagues allowed me to recognise skills and knowledge that I had developed informally through my work as an ESOL practitioner. In particular, the facilitation skills from working with groups and the understanding and confidence from working with people from different countries, different backgrounds and languages. This proved valuable in a community context where other workers who have not had similar experiences do not yet feel confident working with speakers of other languages. One of my non-ESOL colleagues, for example, reflected on her experience of the project.

When I initially became involved with the Cultural Connections project, I was nervous about talking with people from other countries. I was scared I wouldn’t understand them or they wouldn’t understand me. Being part of this project allowed me to develop my understanding of other people’s cultures and share a little of mine. The learning from others was immense (Pam Armstrong, personal communication).

Working alongside ESOL practitioners can help workers in other teams and organisations to develop awareness and confidence of working with speakers of other languages. This is important because a lack of knowledge and understanding of people from other countries can keep people apart. Speakers of other languages can be left to ESOL provision and specific support organisations until they are considered ‘ready’ to take part in the wider society. As such, ESOL can be a way of delaying participation and, consequently, a way of delaying valuable learning. We need, as Griff Foley (1999, p.6) has urged, to ‘break out of the strait-jacket which identifies adult education and learning with institutionalised provision and course-taking’ and remember that much language is learned informally and implicitly. We do not need to first learn the language to then be able to participate in communities and the workplace. We can also learn language through participation.

ESOL practitioners may not have been trained to take an intercultural approach to integration and ESOL but most will have since developed valuable skills. With these skills and through our contacts with different learners and communities, we are well placed to support the work to create spaces for informal learning where people can participate and contribute as equals and learn through interaction with others.

How we do this and how we find people to collaborate with will depend on the context we work in. ESOL practitioners, like ESOL learners, can often be left out of wider networks and discussions. There can be a lot of luck and trial and error involved around finding people to work with. We can keep an eye out for networks and for ways in which priorities of the different partners might overlap. In Scotland, as an example, the recently published plan outlining the Scottish government’s strategy to tackle social isolation and loneliness and build stronger social connections could perhaps provide opportunities to find common cause with other services and organisations (Scottish Government, 2023).

A starting point could come through using the Place Standard Tool (www.ourplace.scot) to structure conversations with ESOL groups. This consists of simple questions around 14 topics relating to both physical and social aspects of a place. It is increasingly being used by local authorities and other organisations in Scotland and further afield and could be a good way to make connections to wider conversations happening in the local area or to identify priorities for change. It could also serve as a way into more participatory approaches in ESOL (Chick, 2023) and a move away from the more linear synthetic syllabus of coursebooks that is at odds with what we know about how people acquire second languages.

These are just two suggestions in addition to the activities that were part of our Cultural Connections project. There are many more examples to learn from, one being the Sharing Lives, Sharing Languages Project (Hirsu & Bryson, 2017). There are different ways to bring people together. What is important, from our experience, is that once people are together things are not left to chance but that thought is given as to how connection and interaction are facilitated. What is also important is that all who take part are seen as equals, rather than some (usually local community members) being seen as volunteers and others (usually speakers of other languages) as beneficiaries, but that all have the opportunity to contribute, be useful and learn.

Ćatibušić, B., Gallagher, F., & Karazi, S. (2021). Syrian voices: an exploration of the language learning needs and integration supports for adult Syrian refugees in Ireland. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(1), 22–39.

Chick, M. (2023). ESOL English classes are crucial for integration, yet challenges remain unaddressed. The Conversation, 15 May.

Chick, M., & Hannagan Lewis, I. (2020). An investigation into the barriers to education and employment for forced migrants in the convergence area of Wales. Welsh Refugee Council.

de Lima, P., & Wright, S. (2009). Welcoming migrants? Migrant labour in rural Scotland. Social Policy and Society, 8(3), 391–404.

Foley, G. (1999). Learning in social action: A contribution to understanding informal education. St. Martin's Press.

Forkert, K., Oliveri, F., Bhattacharyya, G., & Graham, J. (2020) How media and conflict make migrants. Manchester University Press.

Hirsu, L. & Bryson, E. (2017). Sharing lives, sharing languages: A pilot peer education project for New Scots’ social and language integration. Scottish Refugee Council. https:// www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Sharing-Lives-Sharing-LanguagesSummary-June-17.pdf

OECD/EU (2018). Settling in 2018: Indicators of immigrant integration. OECD Publishing.

Phipps, A., Aldegheri, E., & Fisher, D. (2022). The New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy: A report on the local and international dimensions of integrating refugees in Scotland. University of Glasgow. https:// www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_900243_smxx.pdf

Scottish Government (2023). Recovering our connections 2023-2026: a plan to take forward the delivery of A Connected Scotland – our strategy for tackling social isolation and loneliness and building stronger social connections. Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/publications/recovering-connections2023-2026/

Carol Goodey is an Associate Tutor at the University of Glasgow. She first started working in ESOL in 2006 as an Adult Literacies and ESOL Worker with a local authority in Scotland. She has worked in different community roles since then, always with a focus on learning, engagement and connection.

When the Russian Federation's invasion of Ukraine began on 24 February 2022, which was an escalation of the war that had been going on since 2014, none of the Polish were ready for . However, the majority of citizens rose to the occasion. Polish families opened their hearts and their doors to take whole families under their roof and provide them with peace of mind and basic, decent living conditions. We prepared our flats and organized collections of clothing, food and basic hygiene products for Ukrainians. As far as possible, with willingness on the part of the refugees, jobs have been organized and children have been registered in Polish schools.

Knowledge of the differences and similarities between the education systems in Poland and Ukraine has become an important part of the work of the teaching and pedagogical staff at the school where I teach. Unfortunately, most of the information had to be acquired by teachers on their own by searching for information on the Internet or paid courses. Both education systems, in Poland and Ukraine, have recently undergone significant reform. Let us, therefore, look at some of the differences or similarities in both systems. The first important point is primary schools, which accept pupils aged 6-14 in Poland. It is a two-stage education, i.e. primary grades I-III and a second stage of education in grades IV-VIII. As for post-primary schools, in Poland a pupil may continue his/her education in a 4-year high school, a 5-year technical school, or in a trade school, and after passing the matriculation exam, a student may start studying at university or college. As far as the secondary education system in Ukraine is concerned, pupils continuing their education can choose between high school, technical high school, or vocational school, just like in Poland. It should be noted that when a pupil first arrived in a Polish school, he or she was often placed in an integration class made up solely of Ukrainian children; in some cases, children were admitted straight away to the appropriate class or a class a year lower according to our education system.

The school where I work is a primary school in the small town of Stare Bogaczowice, Lower Silesia, Poland. Ukrainian families with children came to the school area. Initially, all the children attended the school, but over time, some of them found their way to other places, which resulted in the pupils moving to other schools, and a few pupils returned to Ukraine after a few months.

Initially, the main objective of the school was to provide the children with care and to be among their peers. Polish language classes for foreigners were implemented to make it easier for Ukrainian pupils to communicate with their peers. Over time, pupils began to join in the learning to a greater or lesser extent.

I must admit that my initial encounters with Ukrainian students were a challenge for me. I had never been exposed to the Ukrainian language before and, as it turned out, the children either did not understand or they seemed to be afraid of hearing it. Their embarrassment when I tried to speak to them in Russian could have been due to two contexts, either the children felt uncomfortable hearing the language of the enemy, or my pronunciation was so radical that they preferred to avoid contact. However, I decided not to give up and introduced games for all pupils at the very beginning. The role of a teacher was taken over by my Ukrainian pupil, who had the task of familiarizing us (classmates and the teacher) with his language. Beforehand, I started to show flashcards with pictures, then we asked him to tell us how the object was pronounced in his language, all the pupils repeated after him, later we said the name of the object on the flashcards in English and Polish. In this way, after 2-3 lessons we were able to move on to polite phrases, requests, or asking simple questions.

Due to this, the pupil felt freer and more valued. He felt he mattered in our school community and was not just a refugee but a student like the others. The school also organized additional Polish language

classes for foreigners, which helped the pupils to master communication between learners and teachers. Our school had the possibility of employing support teachers, who are Ukrainian teachers. Their presence at school and in lessons gives Ukrainian pupils the chance to acquire the same knowledge as pupils with a Polish background. The teacher's work is also made easier in this way, for example, when a Ukrainian pupil does not always understand the teacher's instructions, the teacher receives the full support of an assistant who can translate conversations between learner and teacher. However, this does not change the fact that adapting teaching materials or language teaching methods has become a challenge requiring more commitment on the part of the teacher than before.

One of my biggest challenges as an English teacher was to motivate students to do any kind of learning activity, communicate and arouse interest in the subject. Every lesson that introduced new vocabulary included far more illustrations than I had used before. I was very often supported by the opportunity to play charades in which pupils presented new words through movement to imitate an action or object while the others had to guess what was being presented. In addition to consolidating the vocabulary, there was a lot of laughter. Each time, the class would ask a Ukrainian student what the equivalent word was in their native language. This type of interaction created not only a greater desire to learn but also a sense of belonging to a peer group. However, the stumbling blocks started when trying to explain grammatical issues. Often, Polish pupils have difficulty in understanding a grammatical issue and this requires the teacher to repeat, translate or find another way of explaining the material. In the case of Ukrainian students, there is also the problem of not understanding one hundred percent of Polish and English. At this point, the teacher can use film material, which the student can listen to and see at the same time. He or she can also re-read the film material at home and discuss it with their tutors. All the materials prepared and invented were tested during the lesson, while at the same time, it had to be taken into account that one way might not work, so several different materials had to be prepared in advance. Over time, another problem began to emerge. As time went on and the Ukrainian pupils started to function in the school, they continued to receive support from the support teacher, and, seeing the teaching adaptations for refugees, the Polish pupils started to rebel, viewing this support as discrimination against their own needs. It took me a long time to explain and talk to the students about this. The situation of the Polish pupils feeling jealous and wronged by the school mainly affected the junior classes.

In summary, at the time of the arrival of the Ukrainian refugees, as a teacher, I felt that I was faced with the unknown when teaching Ukrainian students. Any guidance was presented by the school management on an ongoing basis, which often introduced anxiety and chaos. The main reason for this was the ever-changing situation of the number of Ukrainians. All the adjustments I managed to make in my classes were not preceded by any training. The Polish school, teachers, and educators found themselves in a new situation, which they had to accept and adapt by themselves, often by trial and error. Each of us shared our ideas and observations with the pedagogical team, which helped us to run the classes to a satisfactory level. Now Ukrainian pupils have been attending our school for a year and a half. They have been fully accepted by their peers, gaining new friendships and acquaintances. As a teacher, I have already built up a base of my ideas, which will certainly be applied when a pupil from another country comes to our school. Despite the initial difficulties, the experience I have gained has strengthened my knowledge and enriched my teaching, while reminding me of the important role of language teaching in schools. However, I still have many questions and reflections on how to work with refugee children, but like any teacher, I realize that through them I will continue to strive for selfdevelopment to support young people in their education.

Zuzanna Stein - an unconventional English and Geography teacher in Stare Bogaczowice, Poland. Vocational foreign language teacher for adults. Resocialization educator focused on self-development. In class, teaches linguistic intuition through various methods. English translator in the field of psychology and pedagogy. Privately, wife, and mother of two boys.

Stories come in multiple shapes and flavours. Stories are descriptions of imaginary people and events. Stories may also form part of a narrative with true or fictional events or connected sequences. Stories can define identity by dispatching messages, meanings, and feelings emanating from people's narratives.

Storytelling and story-writing in English language teaching is a powerful tool that captivates educators and learners, transcending time, space, and culture. They bridge the gap between teaching and learning, as teachers and story writers skilfully use words to engage and inspire. Language comes alive, empowering learners to immerse themselves in English expression beyond textbooks. Story writing encapsulates diversity that resonates with students' linguistic and cultural backgrounds, expanding their perspectives and fostering empathy. Giving learners the tools to become authors, using language to shape their narratives and cultivate creativity helps them to nurture linguistic skills. It also catalyses language acquisition and enables them to experiment authentically with vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. This captivating realm of English language teaching offers a gateway to cultural appreciation. It is an adventure that educators and learners share, fostering connection, understanding, and personal growth while celebrating identity and language through narrative.

The idea and opportunity to use story-writing in the ESOL class progressively originated from my teaching practice as an English Language educator. When I started teaching a group of ESOL women at the Windsor Women's Centre in Belfast 14 months ago, I met women who wanted to enjoy learning English. They are from diverse backgrounds, refugees, asylum-seekers, economic migrants; they have come to Northern Ireland for a safe and better, or different life. They have been here between one and ten years.

To introduce Windsor Women's Centre, here are a few lines from the Centre's Education Manager, Satya Roberts:

Windsor Women's Centre in South Belfast has been operating since 1990, providing high-quality training and education courses to around 300 service users weekly. They offer free ESOL classes to 40-50 minority ethnic women, addressing barriers and providing childcare support for children between 2 months – 4 years. While the centre no longer offers accredited qualifications since changes to the college policies regarding community ESOL provision, the courses prepare and enable women to achieve those when ready. The centre encourages women to participate in ICT, Numeracy, Art & Craft, Health & Well-being activities, fostering interaction with native English speakers. Other services available to women are Sure Start (Early Years) programmes, Advice and Family Support. The centre views its ESOL provision holistically in the context of overall women & community development ethos. Our experience has shown that these classes (even without accreditation) significantly enhance the learners' confidence and reduce social isolation.

The centre is an anchor point for many women who use its services. Many have not had the opportunity to be part of the community they currently live in because of language barriers and a lack of qualifications and resources to access education or work, making them very isolated. Despite the majority of them being mothers and wives, they feel alone, isolated in their communities and may also

they still want to fit in – many do not have a choice – they did not choose to escape the violence, war or persecution of their countries – they had to in order to survive.

The ESOL women were from diverse places in the world. They had different educational backgrounds, some completed third-level education , and others stopped after primary/secondary schooling. Upon uptake of the ESOL class, their English levels were assessed at high A2 – low B1. Personalities in the classroom were like the rainbow's colours – from degrees of extroversion and expressivity, individuality, selflessness, and attachment – they are symbolic testimonies of the women's journeys, experiences and beliefs, and mutual support in the classroom. They all havdcommon aspirations – to integrate into their new communities, learn English and feel they belonged.

I asked the women what they expected from this class; they said "Of course, we want to learn the language, but not only this, we want a place where we feel safe, learn together, talk about and share our lives because we have nowhere like this." Since then, I have got to know these women as they faithfully attend two two-hour weekly classes; only a handful have left because of family commitments, and new learners have joined. The women's longing for a haven to learn together, to share their lives and to belong firmly resonated with me – they needed to have that sense of belonging, cohesion and community – and our classroom would be that space. I sought to offer the women a reason and a purpose for coming to class.

After the initial introductions, I discovered they had a linguistic and cultural richness and diversity that should be utilised and celebrated in the classroom. All the women shared a solid desire to concretise their belonging in their local communities whilst nurturing and celebrating their home language, family, history and ancestry, culture and heritage. A few spoke two languages, making the classroom multilingual and multicultural. The women's first languages were Albanian, Arabic, French, Kurdish, Mandarin, Portuguese, Somali, Swahili, and Ukrainian, and their additional languages included Creole, Danish, English, French, German, Spanish, and Turkish. When I asked them if they wanted to write a traditional story related to their countries, they replied: "How can we write a story when we have never done this in English and, for most of us, in our own languages?". I explained that the story would be a cultural celebration written in their first languages and English. During this process, they would learn many skills – vocabulary, grammar, collaborative work, research, and putting simple and complex sentences together – in speaking and listening, writing and reading. Indeed, it would be an ambitious but rewarding undertaking. The goal was to write, read and share many different stories in all the first languages present in the classroom and English, to recognise and celebrate the women's identities and cultures and assert themselves as language learners and owners. They were surprised at my request to use their first languages in the English learning classroom. Indeed, as an English second-language speaker and teacher who advocates for learners' voices, I cannot conceive and agree with the idea of learners leaving their identities at the classroom door. Instead, I endeavour to offer them a classroom encompassing a safe and diverse space where language, identity and culture foster conducive learning.

The objective of the traditional story-writing project was not for the learners to create a story from scratch with fictional characters and events. The intent was to use a cultural custom or story specific to each country represented in the classroom and put it into writing in their first language and English. The creative element was still there, whereby the women had to write their stories using language structures in their home languages and in English, representing a task that none had ever engaged in. Thus, in mid-September 2022, the 12-week project got underway with fourteen women. Each two-hour class was divided between writing and learning time, focusing on vocabulary, grammar forms, and sentence structure. As the women had never partaken in such a project, lessons incorporated various collective and individual activities. These included viewing and discussing worldwide traditional stories and celebrations – the Rainbow Serpent from the indigenous people of Australia, the celebration of the Inti Raymi Sun Festival from Ecuador's Indigenous people, the Chinese Dragon Boat Festival, the Arabic Ramadan Custom – and brainstorming about their languages and traditions. The women were encouraged to think about and draft their stories through scaffolded planning worksheets and further scaffolded structured writing. The project gained momentum as the women enjoyed the collective tasks, using and sharing their first languages and researching and planning a topic close to their hearts. The women wrote in class and at home, enjoying the attention and participation of their children and husbands. Writing the stories was a conscientious effort for all the women – some produced drafts,

experimenting with their personal and authentic style as individual writers. Finally, they completed the writing stage just as we took our Christmas holiday break, so we postponed the reading stage to the New Year once classes resumed.

In January 2023, three students did not return due to work and relocation, and it was not until March 2023 that most of the group were once again present in class. The women decided to read the stories on 8th March, which also marked International Women's Day. They felt empowered to read their stories on such a special day. After some time spent in group work for the women to reconnect with their topics and share their stories, five volunteered to read. Nerves kicked in, and courage wavered! The women encouraged and supported each other. Eventually, the five readers shared their stories in their first languages, Arabic, Portuguese, Chinese, and then in English. The other women listened intently, the interest and attention palpable. The readers had never read a story in front of other students before, not in their first languages, let alone in English.

Following the readings, I felt it was important for the women to reflect on their experiences and verbally record their thoughts. Most said that the task made them overcome their fear of reading in English, they felt proud of having accomplished this step. The activity took the women out of their comfort zone and created a sense of great achievement. The sentiment was extraordinary. I also wanted to hear the listeners' thoughts – they shared that listening to the stories in a language most could understand was extremely rewarding and satisfying, and they especially enjoyed hearing stories read in languages they were not familiar with.

To conclude the women's writing and reading part, I asked them to reflect on the whole experience of the project. All reported a deep enjoyment at having written and shared their stories in their first languages, a deep appreciation for each other, and a profound sense of community belonging within the safe shared classroom space.

As a CELTA trainee twelve years ago, I do not recall the practice classroom as a space for learners' first languages and identities. As I started teaching, I quickly decided not to follow that route and that, instead, learners need and benefit from their first languages in the second language classroom. Over the years, my pedagogy has embraced the participatory pedagogy concept, promoting student-centred and participative lessons and giving learners space to learn. As I developed into a knowledgeable and experienced language practitioner, I seized the opportunity to put into practice my beliefs – that learners need to express their voices and identities in the classroom. At this community centre, such a concept has enriched the ESOL women's learning and my teaching practice. Through integrating and sharing cultures and languages in the classroom, our lessons have centred around engagement, understanding, compassion, inclusion and support. The women know and understand that the classroom remains their safe space; it allows them to discuss issues such as families, relationships, marriage, gender equality, feminism, politics, society, etc.

At the time of writing, I have shared the women's experiences with other English language practitioners and volunteers at UK conferences. The project has generally received a positive welcome and interest. It has created or re-awakened discourse around the benefits and constraints of multilingualism, identity, belonging and a two-way societal integration. I plan to complete my research based on this story project by writing a practitioner-based reflective piece using current literature and discourse underpinned by participatory pedagogy, multilingualism and translanguaging.

Juana Simpson is a qualified and experienced ESOL/EAL/ EAP practitioner with 12 years expertise in NI. Juana currently teaches ESOL in the community and EAL in a secondary school in Belfast. She is a passionate advocator for equitable ESOL and EAL provision through her involvement with organisations like NATECLA IoI and NALDIC. With this in mind, her research underpins narrative inquiry through ESOL and EAL learners' voices.

Rebecca Kay and Francesca Stella

Rebecca Kay and Francesca Stella

This short article presents the key findings and recommendations from our recent research project, ‘Language Learning and Migrant ‘Integration’ in Scotland’ (LLAMIS). We interviewed ESOL providers, decision-makers, teachers, volunteers, and learners in Glasgow, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire in 202021. We were interested in their views on how well ESOL provision was working for learners and providers in different parts of Scotland, but also their understandings of who, and what, publicly funded ESOL is for. The project was funded by a British Academy small project grant. Further information about the project including the full report and recommendations as well as video recordings and podcasts from our final workshop are available on our project website https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/socialpolitical/ research/sociology/projects/languagelearningmigrantintegrationscotland/

English language tuition for adult migrants is an area of education closely connected to policies around immigration control, citizenship, and migrant ‘integration’ (Simpson 2019:26). The terrain of language learning and migrant ‘integration’ is deeply political, because it is bound up with power relations between the ‘host’ society and new arrivals, which include diverse and highly stratified groups of migrants. Nonetheless, migrants living in the UK generally recognise the importance of English in their daily lives and their English language needs, while continuing to value their linguistic and cultural heritages and switching between different languages in different contexts (Cooke and Simpson 2009; Cooke and Peutrell 2019).

ESOL classes (English for Speakers of Other Languages), language cafes, buddy schemes and other less structured activities that help migrants develop their language skills play a crucial role in facilitating language acquisition for adult migrants. Access to language learning opportunities can improve migrants’ employment prospects, not only helping them to secure a job, but also to find more secure and rewarding employment better suited to their experience and qualifications. Language learning activities also create opportunities to develop social connections and acquire knowledge about services and sources of support, while also developing migrant learners’ confidence, independence, and feelings of belonging (Stella and Kay 2023: 42-5).

Scotland’s migrant populations have grown and diversified over the past two decades (Kay 2023). Asylum seekers and refugees, those arriving through resettlement schemes and complementary pathways, migrant workers, students, and family members are now living in many different parts of Scotland, some of which previously had only minimal experience of supporting migrant populations (Flynn and Kay 2017; Pietka-Nykaza and Baillot 2022). Provision of ESOL classes and support has grown and adapted as well, with a mix of college courses, community-based classes, befriending schemes, and language cafes available in most larger towns and cities, as well as some much smaller, more rural, and remote settings. Nonetheless, there are still many challenges, with huge waiting lists for classes in cities like Glasgow, and difficulties providing suitable classes for smaller and more widely spread groups of learners in rural settings (Stella and Kay 2023: 25-7).

The significance of language learning opportunities and the need to support these well has been acknowledged by the Scottish government in policy terms. As demand for ESOL grew in the early 2000s, the Scottish government approved two consecutive ESOL Strategies for Scotland (2007-2014 and 20152020). This approach was distinctive in setting up a standalone ESOL strategy, rather than including ESOL alongside literacy and numeracy skills in a wider Skills for Life national strategy on adult education, as happened in England. The ESOL strategies provided guiding principles for ESOL delivery

and dedicated funding to support this and as such also acted as a “framework against which ESOL delivery can (to an extent) be resourced and monitored” (GLIMER 2019:14). Language acquisition supported through ESOL provision and entitlement to access ESOL classes free of charge for asylum seekers as well as refugees on arrival in Scotland has also been recognised as a key aspect of successful settlement in the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (2018-22).

Nonetheless, the last few years have seen a period of significant change and upheaval for ESOL provision in Scotland. Changes to the funding model and channelling of resources through Further Education (FE) colleges since 2018 affected the balance of relationships between third sector, local authority, and FE providers. In some areas this has increased competition for scarce resources and reinforced hierarchies among providers stifling creative collaborations and forms of provision. In other places, third sector providers have been left struggling to fill the gaps in an over-stretched landscape of provision. The decision not to renew the Scotland ESOL strategy in 2020 but rather to incorporate ESOL into a wider Adult Learning Strategy has signalled a lack of strategic vision for the sector and a failure to address issues linked to under-resourced, piecemeal, and disjointed provision (Stella and Kay 2023: 212).

The Language Learning and Migrant ‘Integration’ in Scotland (LLAMIS) project explored the complex landscape of ESOL provision and demand in Scotland by comparing Glasgow, Aberdeen city and Aberdeenshire. The project was funded by The British Academy; qualitative fieldwork was conducted in 2020-21, and included interviews with ESOL providers, decision-makers, teachers, volunteers, and learners. We gathered rich data providing insights into a wide range of perspectives and experiences. We were interested in views on how well ESOL provision was working for learners and providers in different parts of Scotland, but also their understandings of who, and what, publicly funded ESOL is for.

We were inspired in our study by new ways of thinking about the relationship between language learning and citizenship (Cooke and Peutrell 2019) and critical reflections on the emancipatory potential of language learning (Brown 2021), as well as by different models of and approaches to support for language learning. We also received terrific support and encouragement from NATECLA Scotland. We were delighted therefore to have inputs from Pauline Blake-Johnstone, chair of NATECLA Scotland, as well as from Mel Cooke, Peutrell, Steve Brown, Jodi Watson and Sheila MacDonald at our concluding workshop.

The workshop also gave us an important opportunity to discuss our research findings and our recommendations with participants; the latter were revised based on their input. A comprehensive discussion of our research findings can be found in the detailed project report, while a summary of key findings and recommendations can be found in a more concise policy briefing. We conclude this short article by highlighting the recommendations emerging from our research. We hope this can contribute to debates about the future of ESOL and its relation to migration policy in Scotland and in the rest of the UK (Rolfe and Stevenson 2021; Simpson and Hunter 2023).

1. A comprehensive mapping exercise is required to scope need and demand for, and provision of ESOL in Scotland

There is ample evidence of unmet demand in all three of the council areas where we conducted our research yet we do not have a full picture of the geography of ESOL need and demand across Scotland. The landscape of ESOL provision in Scotland has changed considerably because of shifting migration patterns and policy over the past twenty years and presents significant regional variation, yet the last Scotland-wide mapping exercise was commissioned in 2004, to inform the first Scotland ESOL Strategy. The scoping review would require the collection of new quantitative and qualitative data, but can also draw on existing datasets (i.e., demographic data from the latest Scottish census, records from FE and community providers) and should consider new learner groups who are arriving, or are likely to arrive, as a result of current policy developments at UK and Scotland level. These include ongoing changes in the UK asylum and resettlement routes, changes in the UK points-based visa routes for voluntary migrants, and the role of migration in Scotland’s population strategy.

2. Long-term strategic vision and adequate funding are needed to secure effective ESOL governance and provision.

Scotland no longer has a standalone ESOL strategy: instead, ESOL was incorporated into the broader national Adult Learning Strategy 2022-2027, alongside other areas of community adult learning. The Adult Learning Strategy commits to undertake a review of the impact of the Scotland ESOL strategy 2015-2020 and to produce recommendations for this specialism within the context of the Adult Learning Strategy. The current position leaves the ESOL sector without a clear strategy, raising concerns that the distinctiveness of ESOL learners and specialism may be lost. ESOL-related policy needs to centre learners’ diverse needs and aspirations and be informed by consultation with learners and practitioners. Rather than referring to a generic ‘ESOL learner’, ESOL-related policy also needs to have a clear vision about who and what publicly funded ESOL is for. While it is right that the emphasis should remain on the poorest and more marginalised migrants, consideration needs to be given to the fact that ESOL needs are not limited to these groups. Adequate funding is essential to enable the sector to cope with continuing change and avoid an overreliance on unpaid volunteers: a funding strategy should be a key part of a long-term vision for the ESOL sector.

3. A joined-up approach to ESOL provision should reflect the diverse needs of learners and facilitate coordination and cooperation across ESOL providers and with other services supporting migrants.

Our project report (Stella and Kay 2023) outlines the diversity of Scotland’s ESOL learners, providers, and regional contexts. Developing a more joined-up approach to this diversity would enhance coordination and cooperation across the sector but would also require thinking across ESOL and other relevant policy areas such as migration policy; community development and integration policies; and education policies. This more joined-up approach underpins the New Scots Integration Strategy for asylum seekers and refugees, but is much less clearly articulated, for example, in the Scottish government’s thinking about how to attract and retain migrant workers, or how to support family members accompanying them. Our study points to the key role that ESOL activities play in a broader process of settlement for learners, one which includes economic, social, cultural, civic, and political dimensions. Our findings show the importance of centring learners’ diverse needs and aspirations in ESOL provision and understanding their language needs in the context of their wider lives. Devising a framework that starts from the needs of learners rather than drawing boundaries around what is/is not ESOL, or setting hierarchies around accredited and non-accredited learning, would lead to a more joined -up approach to ESOL provision. This joined-up approach would facilitate the coordination of diverse provision and encourage cooperation and innovation across Scotland’s many geographical contexts and between different ESOL providers. It would also incentivise cooperation across ESOL providers and other services supporting ESOL learners and facilitate outreach to hard-to-reach groups.

Our study revealed a rich landscape of ESOL provision in Scotland, with dedicated teachers and volunteers providing a wide variety of classes, language cafes, buddy schemes and other activities. Learners told us of the importance of ESOL activities not only in supporting their language acquisition but also for improving self-confidence, making social connections, accessing other support services and entitlements and improving their employment prospects. At the same time, it was clear that the ESOL Sector in Scotland faces many challenges in a time of significant and multifaceted change. Our report highlights the importance of joined-up thinking across different policy remits (notably education and migration), and of a joined-up approach across college and community ESOL providers, to meet these challenges. Given the diversity of ESOL learners’ backgrounds, experiences, needs and aspirations and the multiple positive impacts of language acquisition and ESOL activities which they told us about, we also argue for the importance of centring an appreciation of learners’ wider lives and language needs in ESOL-related policy. We would love to hear from readers outside of Scotland about how ESOL provision is organised in their contexts and whether our findings and recommendations resonate with their experiences.

Brown, S. (2021) ‘The emancipation continuum: analysing the role of ESOL in the settlement of immigrants.’ British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42:5-6

Cooke, M. and J. Simpson (2009) ‘Challenging agendas in ESOL: Skills, employability and social cohesion.’ Language Issues. 20/1, 19-30.

Cooke, M. and Peutrell, R. (eds.) (2019) Brokering Britain, Educating Citizens: Exploring ESOL and Citizenship. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Flynn, M. and Kay, R. (2017) ‘Migrants’ experiences of material and emotional security in rural Scotland: implications for longer-term settlement.’ Journal of Rural Studies, 52, 56-65.

Kay, R. (2023) More ways to win. Should Scotland adjust its policy priorities on migration?. Edinburgh: Royal Society of Edinburgh

Pietka-Nykaza, E. and Baillot H. (2022) "This is my place" A summary report of the Rural Living Project. Glasgow: University of the West of Scotland.

Rice, C., N. McGregor, H. Thomson, and C. Udagawa (2004) National 'English for Speakers of Other Languages' (ESOL) strategy: Mapping exercise and scoping study. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

Rolfe, H. and Stevenson, A. (2021) Migration and English language learning after Brexit. Leicester: Learning and Work Institute.

Scottish Government (2007) The Adult ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) Strategy for Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

Scottish Government (2015) Welcoming Our Learners: Scotland's ESOL Strategy 2015 - 2020. The ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) Strategy for Adults in Scotland 2015. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Scottish Government (2018) New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018-2022. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Simpson, J. (2019) ‘Policy and adult migrant language learning in the UK’, in Cooke, M. and Peutrell, R. (eds.) Brokering Britain, Educating Citizens: Exploring ESOL and Citizenship. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Simpson, J., Hunter, AM. (2023) ‘Policy formation for adult migrant language education in England: national neglect and its implications.’ Language Policy, 22: 155–178.

Stella, F. and Kay, R. (2023) Language learning and migrant ‘integration’ in Scotland: exploring infrastructure, provision and experiences. Final Project Report. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Rebecca Kay is Professor of Russian Gender Studies in the School of Political and Social Sciences, University of Glasgow. She has many years of experience of conducting qualitative social research, including into migrant experiences of moving to and settling in rural and urban Scotland.

Francesca Stella is Senior Lecturer in Sociology in the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow. Her research and teaching focus on migration, sexuality and gender; she is a long-standing member of Glasgow Refugee Asylum and Migration Network (GRAMNet) and Programme Convenor of the Masters Global Migrations and Social Justice.

Most UK-based ESOL classes in the past have catered for students who make a life choice to come and work or study English in the country. In recent years a different kind of student has arrived, one who has not necessarily come of their own volition or in search of an educational opportunity or new life-work experience, but who is here by force of circumstance, seeking sanctuary from conflict, persecution or human rights violations. Students of this kind may be refugees, asylum seekers or migrants but share the need to learn the language of the country in which they find themselves trying to rebuild their lives. Despite showing remarkable resilience in the face of new challenges, they have often undergone trauma and hardship before coming here and such past experience might well be expected to impact on their current situation, including language learning.

This small study sets out to explore the views of a group of students participating in volunteer-taught English classes on the Isle of Wight (IW), an island lying off the south coast of the UK, where they are living either under temporary sanctuary or with more long-term scope for resettlement. This study seeks to explore how far their migration might affect their motivation and other aspects of learning English.

Community Action IW is a charitable service which supports the island’s voluntary and community organisations, including management of the island’s participation in several refugee resettlement programmes (RRPs) since 2017 and more recent involvement in the Homes for Ukraine scheme (HfU). A small team of staff are supported by a larger cohort of volunteers and, in the case of ESOL provision for those who have fled conflict, violence, or persecution, by a small number of volunteer teachers.

A small-scale study was undertaken by two volunteer teachers with students from classes that they taught. Both had an extensive background in ESOL and had been involved in volunteer teaching for Community Action IW since 2017. The study set out to explore the student perspective of the possible effects of relocation on their language learning. Data were collected through four focus group discussions, involving 13 students. The students were from Syria, Sudan and Ukraine. Participants from the first two countries had come to the UK on various RRPs and the latter on the HfU scheme. The length of time that participants had been living on the IW ranged from three months to five years and two months. Questions used to initiate discussion explored:

• How students had come to relocate/be relocated to IW, how much they knew about it beforehand, and their pre-and post-arrival impressions of it.

• How motivated they felt about learning English and whether they felt they were able to concentrate on learning English.

• Whether aspects of their lives impacted on their learning of English and whether learning English had importance for them now or in the future.

Movement and motivation: exploring the student perspective on displacement, relocation and their impact on learning English

Julie Watson

Three key areas emerged out of discussions. It was felt that the students’ own voices gave powerful testimony and so many of their responses are included here.

Participants’ knowledge of the island prior to relocating varied. All students who came to the UK through an RRP said that IW was put to them as a relocation destination and that they knew ‘nothing’ or ‘little’ about it before they arrived:

”I haven’t got much information about (it). Just I came and saw.“

“Not that much, just a little bit. A map and a small book, they gave me. I checked on the map. Small Isle of Wight and I saw bus station and towns; Ryde and Newport and Cowes.”

In contrast, HfU students were able to make more of a choice and inform themselves, before relocating to IW, citing for example: having Ukrainian friends, relatives or a potential host on IW, or having made a previous visit here. They also gathered more pre-arrival information from contacts made on social media:

“I watched YouTube, I read some information on the internet and I decided to move here for holiday. I found a house. I wanted to live in the area - a green area, with many English people.”

With or without making a choice beforehand, students from both groups reported experiencing changes in their feelings towards being on IW. RRP students admitted having high expectations, which, in some cases were met and in others not:

“I imagine live near the sea and children go to school - because in Jordan, they can’t. Everything in UK is sure - health system, food, drink, transportation. I imagine weather in UK very nice - not hot not cold.”

“The first time I came here, I surprised; I disappointed. It’s big difference if you compare with my country you can’t contact with the people. Because in my country you can say hello any time to your neighbour, and you can have coffee or tea with them and here when I came I feel little bit bored and disappointed with a lot of things.”

“When I came, I had family here. After 2 months I was looking for a job for like 10 months. I didn’t find anything. That is big disappointment.”

HfU students often cited feeling ‘safe’ on IW, but also felt prior expectations were not of particular relevance since they felt rather conflicted about being there:

“All (the) time, I wanted home It was very difficult. It’s not about the IW. It was difficult to (go to) another place. I’m lucky here.”

“I didn’t think about anything but only I have children and if I have (the) chance, I come. That’s all.”

“The first time I think we go and return (to Ukraine) but now I want stay and I want (my) daughter (to come) to stay here. but maybe one or two years.”

Their ambivalence was summed up by one as, ‘all my things in Ukraine; all my heart in Ukraine.’

Limitations such as lack of Halal food outlets (for Muslims), and lack of opportunities to meet children’s future educational needs were mentioned, yet so too were advantages of IW over city life. In some cases, students admitted changes in their feelings after a few months, despite initial disappointment. A small number of students from both groups reported feeling immediately settled and ‘happy’ on IW.

Research in the field sometimes refers to the possible impact of a combination of complex stressors that might affect second language learning, particularly focusing on motivation (Palanac, 2019; Kerka, 2002, cited in Gordon, 2011; Watson, 2020), and concentration (Gordon, 2011). The RRP students in the present study claimed that they had no problem regarding their motivation to learn English:

“Yes sure. All time, study English at home - YouTube at home Every day I try learn English.”

In general, HfU students echoed their certainty:

“Yes I have motivation because I want to understand the personnel in the hospital, in the bank, everywhere.”

For many however, distractions and worries (family and personal responsibilities, caring for children or elderly family members and their wellbeing) were cited as factors that limited their time and energy for language learning, and affected their concentration:

“Sometimes – I’m so busy – a lot of things to do for the home for the kids and (studying English) without working for four years.”

“I have time, but many times I think about Ukraine, reading news, and this not good for my concentration. Learning English, my brain switch off.”

“We have war now even today I want to study something at home (but) I’m thinking there. And I’m holding my cellphone so I can check there everywhere. I want to hear what’s going on. I’m so worried about it you know - all my relations are there.”

Issues with memory (‘I think I need medicine for my memory’), ageing factors among older students (‘Nothing can help me because I have bad memory and bad hearing’), preoccupations (‘I feel the shadow of Ukraine’) and anxiety (I cannot because all time feel a lot of pressure, pressure, pressure.’) impinged on concentration, bearing out similar findings from previous research (Gordon, 2011).

So, while all students claimed to feel motivated to learn English, they were more hesitant about having the necessary concentration for the task.

Alongside motivation and concentration, students who had been here the longest and those most recently arrived mentioned experiencing external challenges to progressing their English language learning:

“I like to learn to speak in the street. In (my country), all people visit us in the morning in the night; here ‘no’. I hope more speaking. I don’t have English friends. I take my children to school and go back home.”

“Always, I determined to do things but I want to do all things together. Working and studying. Because I’m doing full-time job and I’m doing study. I have family; I have other things -learning swimming even I take my kids with me learning football, all of us learning English. (It’s a) very busy time.”

Nevertheless, the role of English in their lives was acknowledged to be important, not just for the present time ( for ‘better job and speak with English people’), but also for the future, regardless of personal circumstance:

“You know, here is good (for learning English). I’m not gonna say, it’s not good. If you wanna live here, for us it’s a bit different. We are thinking for the future - the mainland. In a city. I don’t mind. It’s just good to get everything for us: for work, for the kids. For the time (being), this place is good.”

All participants were unhesitating in affirming that English has a role in their lives beyond the present, whatever the future might hold:

“For everything for people, for children, for school, for life. All the time.”

“Of course, this is international language - we use it. Our future – where is our future? Who knows.”

“For us too, we need to go back when our country safe. Even if I’m not here, English is useful.”

“I like to learn English for future - we should do test for citizenship.”

Affective factors and external barriers apart, there was agreement that learning English was useful for both now and the future.

The students who took part in this small study included those hoping their stay on IW would be of a limited duration (until a conflict at home has come to an end) as well as those who stated that they ‘never’ wanted or expected to go back to their home country or country of origin. Some could be described, at least physically if not always mentally, as ‘settled’ on IW; others clearly felt themselves to be in a state of limbo. All, however, showed themselves to think deeply about their own situation and were able to provide some valuable insights into the impact that movement to a small island in the UK has had on them as they face the challenge of trying to learn a new language.

I wish to express my gratitude to my co-researcher and fellow volunteer teacher, Jacky MacDonald, and to all of the students from our classes at Community Action IW who willingly gave of their time to participate in the focus group discussions and who voiced their opinions about their experiences so thoughtfully.

Gordon, D. (2011) ‘Trauma and Second Language Learning among Laotian Refugees,’ Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement: Vol. 6 : Issue 1, Article 13. DOI: 10.7771/21538999.1029 Available from: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jsaaea/vol6/iss1/13

Kerka, S. (2002). ‘Trauma and adult learning,’ ERIC Digest. Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult Career and Vocational Education. (ED472601)

Palanac, A. (2019). ‘Towards a trauma-informed ELT pedagogy for refugees’. Language Issues, 30(2), pp. 3-14

Watson, J. (2020) ‘Refugees resettling on a small island: the volunteer language teachers’ perspective’ Making Home Away Project , Lost and Found: Testimonies of Migration, Resettlement, and Displacement, University of Reading. Available from: https://makinghomeaway.com/new-now/languageteachers-perspective/

Julie Watson is a volunteer ESOL teacher of refugees, retired and living on IW. Her professional background lies in TESOL and tertiary education in the UK and other countries. She is also an author and her most recently published book, Travel Takeaways, includes several stories about refugees encountered during her travels.

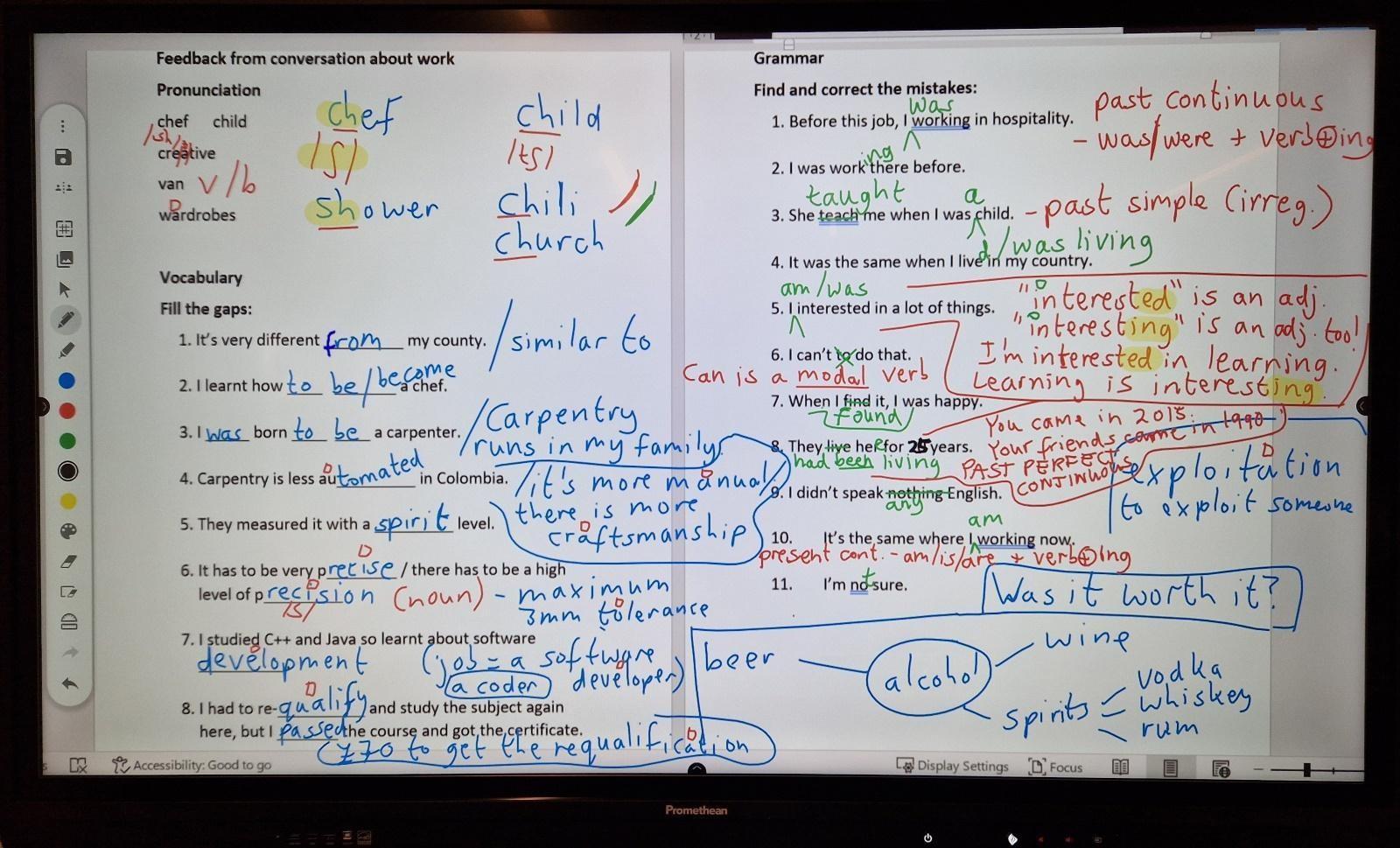

English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) is an area of education in the UK (United Kingdom) which is distinct as it differs from both wider UK education and wider English Language Teaching (ELT). Whilst ESOL practice shares commonality with other areas of ELT, in that it is focused on the development of learners’ linguistic abilities in English (Education and Training Foundation, 2021), it is also concerned with the integration of those adult (or 16+) migrant learners into an English-speaking environment (DEMOS, 2014).

When teaching ESOL in the UK, an ESOL teacher may attempt to incorporate ELT materials into their ESOL teaching practice. This may be due to necessity, workload or time constraints or simply due to the lack of ESOL resources being available. However, differences between the standard English (SE) (Trudgill, 1999) used in ELT textbooks or other resources used in class and the way English is used in the local environment, may also be encountered. Moreover, learners may even highlight these differences or produce them in their emergent language. This article aims to explore the challenges and appropriacy of ELT materials when used in ESOL contexts in the UK and how we can aim to alleviate the difficulties that learners have with the differences between SE used in class and the way English is used in their local environment.

The Adult ESOL curriculum and the resources for each proficiency level (Department for Education and Skills, 2003) have provided ESOL practitioners with a set of materials and a structure which can be used to underpin their courses. However, despite the effectiveness of the curriculum in specifying the target language required at each level and its ease of use and accessibility to an ESOL practitioner, no further revisions to the curriculum have been made subsequent to its publication. Additionally, there is a distinct lack of updated resources produced by the UK government, since the Skills for Life resources were published 20 years ago (Department for Education and Skills, 2003). This has caused ESOL teachers considerable challenges with how to discern which materials are appropriate to meet the needs of their ESOL learner cohorts, as the Skills for Life materials are now considerably dated. Additionally, due to the heavy workloads that ELT teachers contend with, it has become standard practice to rely upon textbooks as they drastically minimise preparation time (Akbari, 2008). These considerations have caused some ESOL teachers to source materials from different areas of ELT such as EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbooks, which are of varying degrees of appropriacy as they are intended to be used with a different subset of learners.

EFL textbooks often do not consider language learners who may belong to groups such as asylum seekers or refugees, who are prominent in ESOL courses. If these groups of learners are actually mentioned, the language used can be problematic. This is exemplified in widely used textbooks such as Soars and Soars (2019) which asks learners to consider if their countries have the same “problems” with refugees or the Iraq/Mesopotamian war as Roman Britain did. This activity would be highly inappropriate for ESOL learners who may be refugees or seeking asylum as they as individuals are being reduced to problems to be solved. This example explicitly highlights a fundamental lack of consideration for ESOL language learners and their lived experiences within a coursebook intended for English language learners. Additionally, the use of entrepreneurs and successful businesspeople as aspirational figures exemplifies how ELT coursebooks are often underpinned by neoliberal ideals. Gray (2012) highlights that ELT textbooks promote the link between learning English and professional success in the global market by having learners aspire towards becoming successful, akin to the aspirational figures living luxurious lifestyles that they choose to feature. Whilst this may be motivational for some learners, it fundamentally ignores the lived experiences of some demographics of ESOL learners, such as asylum seekers, who do not have the right to work in the U.K (UK Visas and Immigration, 2021). Whilst ESOL learners have been considered to some degree in recent publications with mapping to the Adult ESOL curriculum (Steeds,

Exploring

appropriacy