ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 2022

—

Working together towards shared goals

Proceedings of the third ELTRIA conference

Online, 22-23 April, 2022

Published by IATEFL

2 – 3 The Foundry

Seager Road

Faversham

Kent ME13 7FD

UK

Copyright for whole publication

© IATEFL 2022

IATEFL retains the right to reproduce part or all of this publication in other publications, including retail and online editions. Contributions to this publication remain the intellectual property of the authors. Any requests to reproduce a particular article should be sent to the relevant contributor and not IATEFL. Articles which have first appeared in IATEFL publications must acknowledge the IATEFL publication as the original source of the article if reprinted elsewhere.

Disclaimer

Views expressed in this publication ELT Research in Action: Working Together Towards Shared Goals are not necessarily those of the editor(s), of the IATEFL Research SIG, of IATEFL, its staff or trustees.

ISBN 978-1-912588-46-6

Edited by Jessica Mackay & Thomas Wogan

Cover design and book layout by Leonel Brites

Cover Photography: Casa Jeroni Granell

- Catalan Modernisme (1902, Jeroni F. Granell), by Mutari (image on Public Domain).

The International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language was founded in 1967. It is registered as a charity (1090853) and registered as a company in England (2531041). For further information about IATEFL, please see the IATEFL website: http://iatefl.org. For further information about the Research Special Interest Group, please see the ReSIG website: http://resig.weebly.com.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 2022

—

Working together towards shared goals

———————————————

Proceedings of the third ELTRIA conference

Online, 22-23 April, 2022

Edited by Jessica Mackay

Thomas Wogan

———————————————

Preface by Richard

J Sampson

07 Preface

Richard J. Sampson

11 Acknowledgements

13 Notes on contributors

17 ELT research and practice in a changing world

Jessica Mackay

SECTION 1· Classrooms in transition

Developing and adapting to changing conditions

23 Learning languages in Higher Education following the Covid-19 pandemic: student perspectives

Jean M. Jimenez and Ida Ruffolo

33 How does feedback work in an online exam preparatory course? Insights from a teacher research project

Anna Soltyska

41 Following the footprints of online ESP learning: action research

Amalia Babayan

SECTION 2 · Beyond the classroom: Maximising learning opportunities

47 Using Moodle increases older adult language learners’ autonomy and motivation

Jodi Wainwright

51 The timeliness of written corrective feedback in a classroom WhatsApp group: A comparison of two feedback modalities and learners’ perceptions

Bridget Murphy

59 Teacher-talk and Facebook: An enquiry into pedagogical and methodological expectations of GenZ EFL learners in Germany

Kevin F. Gerigk

65 The use of captioned-video viewing to support the development of L2 reading skills

Daniela Avello and Carmen Muñoz

71 Views from the field: Extract from an Interview with Professor Brian Tomlinson

Brian Tomlinson and Jessica Mackay

5

Contents

SECTION 3 · Views from within: Learners’ and teachers’ perspectives on classroom practices

81 Learner-initiated translanguaging: How do Japanese EFL learners initiate interaction?

Seiko Harumi

85 Research into L+ study emotions: Practitioner-researcher suggestions for future directions

Richard J. Sampson

93 Motivated to Get an “A” Katherine L. Kiss

97 Language Teachers’ Perceptions of Classroom Action Research Stephanie King

103 Teachers’ beliefs about CLIL limitations: a case of one Catalan secondary school Anastasia Lovtskaya

109 Positioning language teachers’ professional knowledge in participatory research: Reflections from the front Diane Potts

6

Contents

Preface Richard J.

Sampson

intheproceedingsof the second ELTRIA conference, Graham Hall (2020) commented that “in our busy daily working lives, it is often difficult to ‘take time out’ in order to think about why we do what we do” (p. iv – emphasis added). As I write, we appear to be approaching the latter stages of a pandemic that has wreaked substantial damage to health and welfare around the world and put significant strain on basic economic and educational aspects of society. Wildfires tear through various parts of the world and days with temperatures over 40 degrees Celsius become less of an anomaly. While “guerilla” rain events cause devastating flooding, drought plagues other areas. At the same time, humans seem increasingly polarized in our views, even as we strive to become more inclusive of diversity and aware of historical inequalities. At this juncture, it may indeed be fruitful to consider the “why” of English Language Teaching Research in Action.

In this preface to the third installment of the ELTRIA conference, I would thus like to unpack a little some perspectives on the conference theme: Working together towards shared goals. As a practitioner-researcher, I conduct enquiries with students into our practices in our contexts of learning. The first word from the conference theme upon which I have chosen to focus – “together” –thus for me primarily implies teachers and learners. Over the years, I have found small-scale classroom research to offer learning opportunities for both myself and my students above and beyond the language study in which we are primarily involved. Naturally, “together” might equally imply connections between learners, teachers, teacher-educators, graduate students and academics.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 7

Yet, it is here that I feel the phrase “shared goals” takes on vital importance. Almost twenty years ago, Lourdes Ortega (2005) asked “for what and for whom is our research?” In an impassioned article, Ortega argued for the need in the field of Second Language Acquisition to judge research by its social and educational utility. As a practitioner-researcher, the assertion that research activity ought to have some direct, practical benefit for those involved goes without saying. That is, the “goal” is deeper understandings of our educational processes and behaviours, as well as possibly improvements to classroom life, that are “shared” directly by participants in the research. We may also work towards “sharing” our insights with the wider community of those involved in language learning and teaching, with the “goal” that such an endeavour might have a concrete impact on society and education (Ortega, 2005). We ought not to be in the business of researching or theorizing simply for the sake of researching or theorizing.

I was fortunate enough to be able to travel to the first installment of the ELTRIA conference in Barcelona in 2017, as well as participate online in this third edition. I do admit that online I missed the invaluable conversations with fellow participants over thick black coffee in the beautiful courtyard around which the physical conference centred. (This said, we must contemplate the future format of conferences like ELTRIA, given the post-pandemic realization of being able to do online a lot of what constitutes a conference without producing a huge carbon footprint.) Regardless, in both formats, I have been treated not only to a truly thought-provoking assortment of featured presentations, but also a collection of general presentations and workshops that have inspired me in my teaching and research. To this end, certainly from my perspective as a practitioner-researcher, I truly feel that ELTRIA offers a space for like-minded educators to come together and learn, sharing our goals for more contextualized, nuanced understandings and pedagogy. Via such conferences, and the many insightful papers collected in this volume, we have an opportunity to share our ideas and develop our own teaching, as well as pedagogy and theory in general. It might be wishful thinking, but

8 PREFACE

recalling the tone with which I commenced this preface, I would also hope that in doing so we are playing even a small part in affording our learners an additional voice towards moving human society closer to a sustainable and just future.

References

Hall, G. (2020). Preface. In J. Mackay, M. Birello, & D. Xerri (Eds.), ELT research in action: Bringing together two communities of practice (pp. iii–iv). IATEFL.

Ortega, L. (2005). For what and for whom is our research? The ethical as transformative lens in instructed SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 89(iii), 427–443.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 9

Acknowledgements

thisisthethird edition of the ELTRIA publication. From the outset, this project has been inspired and supported by the IATEFL Research SIG. Past and present ReSIG coordinators and committee members have taken multiple active roles in the ELTRIA conferences and the subsequent publications, as speakers, moderators, reviewers, editors, publicists and consultants. The current ReSIG coordinator, Ernesto Vargas Gil, and the ReSIG committee have continued this tradition of encouragement and invaluable advice, for which we are truly grateful. Thanks also to Leonel Brites for his patience, professionalism and expertise in the design and format of this book.

As ELTRIA conference organiser, Jessica particularly wishes to express her gratitude to her colleagues at the Escola d’Idiomes Moderns (School of Modern Languages) at the University of Barcelona. These include the coordination, and administration team: Berta Barreda, Ciarán Canning, Jon Gregg, Sean Hurson, Mireia Ledesma, Raúl Mera, Yolanda Murcia, Xavier Navarro, and Adriana Peña and the organising committee and volunteers who contributed so much to the success of the event: Marilisa Birello, Judith Dunan, Wolfgang Esienhuth, Aaron Feder, Sean Hurson, Gerard McLoughlin, Vera Trager, Miguel Vega and Tom Wogan. Special thanks go to Ryan Gornall (TESOL Spain) for his expert coordination of the first online edition of the conference.

I would like to particularly thank the scientific committee, who gave up their time and contributed their specialist expertise: Dr Maria Andria, Dr Marilisa Birello, Dr Elisabet Comelles, Dr Natalia Fullana, Prof. Sarah Mercer, Dr Imma Miralpeix, Dr Mireia Ortega, Dr Àngels Pinyana, Dr Raquel Serrano and Dr Elsa Tragant. The conference committee, speakers and authors are greatly indebted

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 11

to them for their care and attention in the review process, which provided invaluable feedback on the submissions for this publication, and by so doing, contributed enormously to the depth and breadth of the content.

Needless to say, we wish to thank the ELTRIA presenters, who joined us from around the world, from different and not-always-compatible time zones, to share their knowledge and experience with us. The geographical and contextual diversity of the event was not only enriching, but also inspiring, as we discovered how much we had in common. Finally, of course, the editors would particularly like to express their gratitude to the contributors who have worked so hard to translate their presentations into the chapters in this book. We hope you enjoy the results of your efforts as much as we have. It has been our pleasure and privilege to work with you throughout this process.

Jessica Mackay Thomas Wogan

12 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Notes on contributors

Daniela AVELLO

Universitat de Barcelona, SPAIN diag08041@gmail.com

EFL teacher (USACH, Chile), MA in Applied Linguistics (UB, Spain), PhD in Applied Linguistics (UB, Spain). Her doctoral dissertation was titled “L2 learning from captioned-video viewing in primary school students.” Her research interests are foreign language learning and teaching, vocabulary learning, receptive skills development, individual differences, L2 learning from audiovisual input and young learners.

Amalia BABAYAN

Faculty of International Relations, Yerevan State University, ARMENIA

amaliababayan3@gmail.com

amalia.babayan@ysu.am

Amalia Babayan is an associate professor at the Faculty of International Relations of Yerevan State University, Armenia. She currently teaches English for Diplomatic Intercourse, Diplomatic Correspondence, Aspects of Diplomatic Language and Area Studies. Her research interests lie in methods of language teaching, ESP/EAP, communicative strategies, materials development, course design.

Kevin Frank GERIGK

k.gerigk@lancaster.ac.uk

University of Lancaster, UK

Kevin F Gerigk is a doctoral researcher in the field of Corpus Linguistics and TESOL. His research interests include the development of corpus-informed teaching materials and methods. He has been a language educator and lecturer for more than 11 years. He has taught in secondary and Higher Education in the UK, Germany and Chile.

Seiko HARUMI

SOAS, University of London, UK sh96@soas.ac.uk

Seiko Harumi is a Lecturer in Japanese and Applied Linguistics (Education) at SOAS University of London. Her academic interests lie in classroom silence, classroom discourse, pragmatics, translanguaging and learner-centred reflective approaches in second language learning and language pedagogy.

Jean M. JIMENEZ

University of Calabria, ITALY jean.jimenez@unical.it

Jean M. Jimenez (PhD) is Associate Professor of English Language and Translation at the University of Calabria, Italy, where she teaches EAP and ESP to undergraduate and graduate students. She is the Coordinator of the Degree Course in Linguistic Mediation. Her research interests include Corrective Feedback in CALL, Language Testing, and the use of Corpus Linguistics in the second language classroom.

Stephanie KING

University of Essex, UK

sk16139@essex.ac.uk

Stephanie King is currently an Academic Leader for EAP and Academic Skills at an international pathways college. She is currently a PhD candidate researching Classroom Action Research: teachers’ perceptions, practice and professional development. Her interests are teacher autonomy and the impact of insider research.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 13

Kate KISS

University of Massachusetts, Boston, USA katherine.kiss@umb.edu katefromumb@gmail.com

Katherine Kiss is a senior lecturer in the faculty of applied linguistics. She currently teaches courses on methods and materials in FL teaching, theories and principles of SLA, culture and Culture in the language curriculum, and coaches students in their final field experience for their degree.

Anastasia LOVTSKAYA

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, SPAIN anastasia.lovtskaya@gmail.com

Anastasia Lovtskaya is a PhD student in Education at the UAB (Autonomous University of Barcelona, UAB). Her background is in teacher development in EFL & CLIL (UAB), and in business studies (Edinburgh University). She works as an EFL teacher and academic coordinator at FIAC language school.

Jessica MACKAY

Universitat de Barcelona, SPAIN jmackay@ub.edu

Jessica Mackay, Dip TEFLA, MA and PhD in Applied Linguistics, University of Barcelona. She is an EFL teacher, CELTA trainer and head of teacher training and development at the UB’s Escola d’Idiomes Moderns (School of Modern Languages).

Carmen MUÑOZ

Universitat de Barcelona, SPAIN munoz@ub.edu

Carmen Muñoz is Full Professor of Applied Linguistics at the University of Barcelona. Her research interests include the effects of age and context on second language acquisition, young learners in instructed settings, individual differences, bilingual/multilingual education, and multimodality in language learning. She has coordinated several funded research projects, and in 2016, she was awarded the Eurosla Distinguished Scholar Award.

Bridget MURPHY

Universitat de Barcelona, SPAIN

bmurphy5252@gmail.com

Bridget Murphy is currently a PhD student and doctoral researcher in Applied Linguistics at the University of Barcelona, Spain. She has 10 years of EFL teaching experience in the US and Spain. Her research interests include mobile-assisted language learning, online interaction, and classroom research.

Diane POTTS

University of Lancaster, UK d.j.potts@lancaster.ac.uk

Dr Diane Potts is a researcher and lecturer at Lancaster University, UK. At Lancaster, she teaches MA modules on social approaches to SLA, language teacher development and digital language language learning as well as PhD modules on research methods. Her prior teaching experience includes applied linguistics for teachers, teaching methodologies for additional language learners (EAL, EFL, ESL), intercultural communication and language socialization in multicultural contexts, and language maintenance and the integration of immigrants in Canada.

14 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

Ida RUFFOLO

University of Calabria, ITALY

ida.ruffolo@unical.it

Ida Ruffolo (PhD) is a Researcher in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Calabria, Italy, where she teaches EAP and ESP. She is a Member of the Faculty Board of the PhD Program Politica, Cultura e Sviluppo (Field of study: Language analysis and interdisciplinary studies). Her research interests are Corpus Linguistics, Discourse Analysis, and ESP, with particular interest in the language of tourism.

Richard J. SAMPSON

Rikkyo University, JAPAN rjsampson@rikkyo.ac.jp

Richard J Sampson (PhD, Griffith University) is an Associate Professor at Rikkyo University, Japan. He teaches courses in English communication and language learning psychology. His research focuses on learner motivation, emotions, and possible selves. He uses action research to explore experiences of classroom language learning from the perspectives of students.

Anna SOLTYSKA

University Language Centre, Ruhr University Bochum, GERMANY

anna.soltyska@ruhruni-bochum.de

Anna Soltyska is a member of academic staff at the Ruhr-University in Bochum, Germany where she coordinates the English programme at the University Language Centre. Her current research interests include implications of AI tools for language teaching and assessment, assessment literacy in post-pandemic conditions and various aspects of assessment-related malpractice.

Brian TOMLINSON

University of Liverpool (UK) and Anaheim University (USA)

Brian Tomlinson has worked as a teacher, teacher trainer, curriculum developer, film extra, football coach and university academic. He is Founder and President of MATSDA (International Materials Development Association), a Visiting Professor at the University of Liverpool and a TESOL Professor at Anaheim University. His most recent (of over 100) publication is: SLA Applied: Connecting Theory and Practice (CUP, 2021) with Hitomi Masuhara.

Jodi WAINWRIGHT

Open University, UK

jodi.wainwright@hotmail.co.uk

Jodi Emma Wainwright EdD. MEd. BSc. is a research fellow with the Open University and the University of Bedfordshire. She teaches English at the Institut National des Sciences Appliqués in central France. She is interested in the use of technologies in blended learning environments, particularly with older adults.

Thomas WOGAN

tom.wogan@cambridge.org

Cambridge University Press and Assessment, Spain

Tom Wogan has worked as an EFL teacher in various countries and as a DOS in a university language centre in Spain. He now works for Cambridge University Press and Assessment as Learning and Assessment consultant in the area of Andorra, the Balearics and Catalonia.

15 ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION

ELT research and practice in a changing world

Jessica Mackay

wheniwaswriting the introduction to the previous ELTRIA publication in March 2020, the COVID crisis was just beginning to take hold. Looking back, we were little prepared for the extent, the duration and the long-term effects of this global event. The experience of the last two years has brought about profound changes in all our lives, both personally and professionally, and many of these have been reflected in the presentations at the online ELTRIA conference in 2022 and, as a result, in this collection of papers.

The emergency transition to remote teaching propelled us unceremoniously, and perhaps unwillingly, forward along our own learning curves, forcing us to adopt and manage new tools and new modes of communication. Despite their precipitous introduction, many of these ‘new’ methods have proven their worth in language learning and teaching and are undoubtedly here to stay, to such an extent that the expression ‘new normality’ already seems clichéd, and we can hardly remember a time when we didn’t have these multiple options available to us.

Therefore, many chapters examine the current realities of our profession. In the last publication based on the ELTRIA conference (2020), only four chapters focused on learning in an online environment, or the use of online tools and applications. In contrast, in this edition, this number has doubled. In Chapter 4, Jodi Wainwright explores the use of learning management systems, such as Moodle, to enhance the motivation and autonomy of older adults learning EFL. We look at the potential technology provides for learning beyond the classroom, for example using the WhatsApp messaging

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 17 introduction

app (Bridget Murphy, Chapter 5) or through captioned-video viewing (Daniela Avello & Carme Muñoz, Chapter 7). And of course, we cannot ignore the presence of social media in our learners’ lives, discussed in Kevin Frank Gerigk’s timely analysis of the expectations of GenZ EFL learners (Chapter 6).

Unsurprisingly, a number of contributions reference the challenges we have faced both during the period of emergency remote teaching and the return to face-to-face classes. Jean M. Jimenez and Ida Ruffolo analyse students’ perspectives on language learning in higher education post-pandemic (Chapter 1) while Amalia Babayan’s action research project compares learners’ and teachers’ experiences of online ESP courses and the return to in-person teaching (Chapter 3). A major issue faced by teachers during this period is examined by Anna Soltyska (Chapter 2) in her discussion of how best to provide feedback in an exam preparation course which was moved online during 2021.

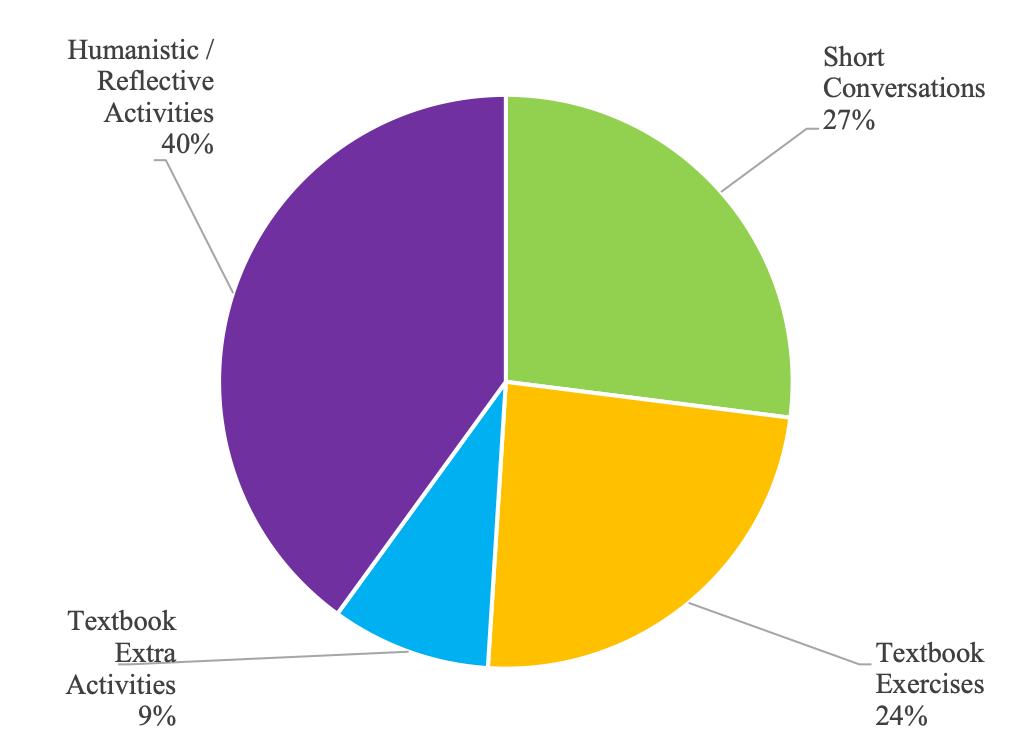

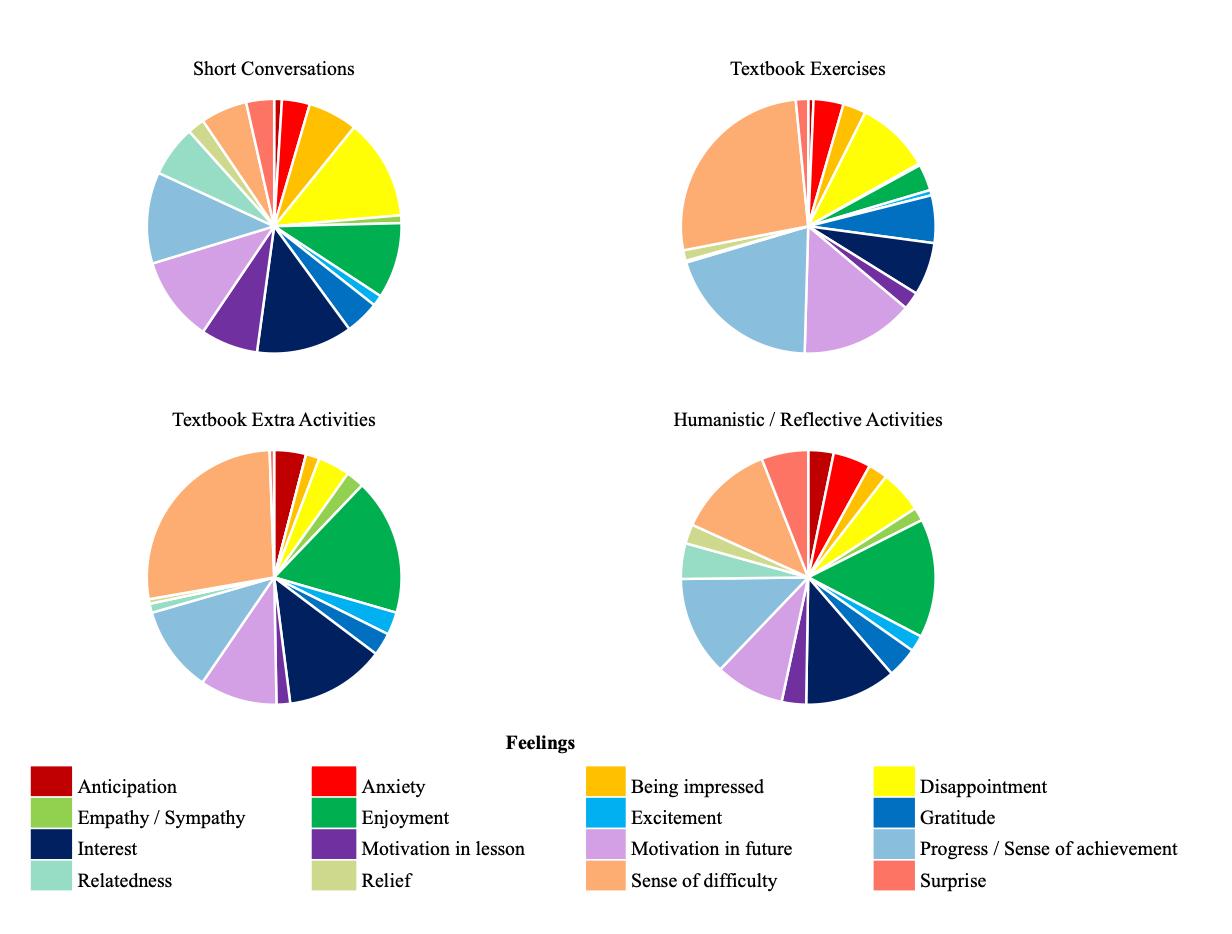

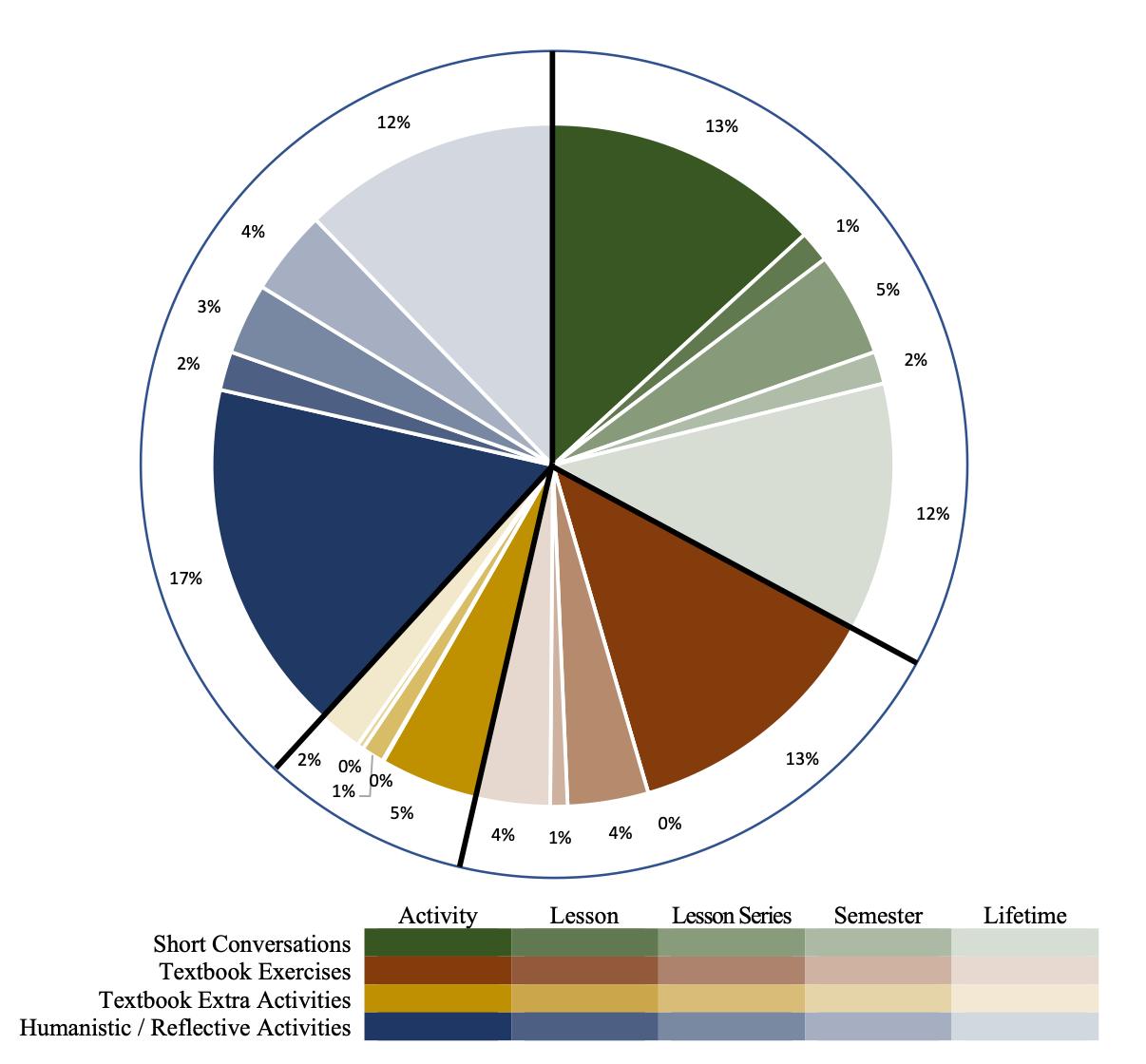

Nevertheless, in spite of all these developments, this volume also touches upon timeless questions and debates in the world of language learning and teaching which, to a large extent, transcend the context in which the activity takes place. Seiko Harumi explores the use of the learners’ own language through the lens of ‘translanguaging’ in chapter 9. Kate Kiss (Chapter 11) touches on the vital and yet elusive concept of learner motivation in her discussion of how it is affected by grades awarded and learners’ perceptions of self-efficacy. Equally influential, the role of emotions in the learning process seemingly defies observation. Richard Sampson presents some of his pioneering work in mapping the fluctuation and evolution of emotions over a lesson (Chapter 10).

The remaining group of chapters focuses on issues in research and teaching from the teacher’s perspective. Stephanie King (Chapter 12) reports on a Classroom Action Research training programme and finds parallels with her experience of presenting at ELTRIA. In chapter 13, Anastasia Lovtskaya summarises her qualitative research on secondary school teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards

18 INTRODUCTION

CLIL. Chapter 8 is an extract from the interview conducted as the introductory session to the ELTRIA conference, in which Brian Tomlinson reflected on topics as diverse as the research-practice divide and learner choice. He concludes the interview with selected examples of success stories from his long and varied experience. The ELTRIA collection concludes with Diane Potts’ fascinating reflection on the challenges, frustrations and imbalances she has encountered in her work with teachers involved in participatory research (Chapter 14).

An initial glance at the contents page of this edition of the ELTRIA publication might suggest a range of themes as diverse as the lives and contexts of the different contributors. I would argue that the common theme that unites all these areas of interest is that of collaboration. Whether this is action researchers sharing their insider views on working with their students or researchers working to explore and articulate teachers’ and learners’ perspectives, ultimately, the aim of each of the projects behind these contributions was to understand and improve the teaching and learning experience: researchers, teachers and learners working together towards shared goals.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 19

SECTION 1

Classrooms in transition: Developing and adapting to changing conditions

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 21

CHAPTER 1

Learning languages in Higher Education following the Covid-19 pandemic: student perspectives

Jean M. Jimenez and Ida Ruffolo

Introduction

The outbreak of Covid-19 and the subsequent emergency lockdowns profoundly affected all sectors, including education, where we experienced a sudden shift to Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al, 2020) which led to “a fundamental change to core teaching and assessment processes” (Cranfield et al., 2021, p.1). This emergency course delivery mode, which differs from traditional online courses designed to be delivered remotely from the start, meant having to suddenly move from our comfortable face-to-face classrooms to an online world with which many teachers and students were unfamiliar or unprepared for. While studies have been published on the effects of this transition considering both teacher and learner perspectives (e.g., Coman et al., 2020; Cranfield et al., 2021; Means & Neisler, 2021), less has been written on the effects post lockdown (e.g., Almuraqab, 2020).

This chapter will focus, in particular, on the experiences of students at the University of Calabria (Italy) who attended a B1 level preparation English course during the 2021 fall semester, after a period of national and regional lockdowns. Due to space limitations dictated by the strict Covid-19 emergency regulations imposed by the University, which established that classrooms could not exceed 25% capacity, some groups of students attended courses on campus while others continued to attend courses online. Data on the students’ perceptions and attitudes towards the course delivery

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 23

mode were collected by means of a questionnaire administered at the end of the semester. The study aims at providing some insights for both academic instructors and university authorities in order to continue to improve didactic experiences. Moreover, while at first it seemed that this ‘emergency’ online delivery mode would only be temporary, it would appear that Covid-19 will be present globally for years to come, hence it is important to consider how this will affect language education and how we can be better prepared for possible future restrictions which may require us to once again leave our in-person classrooms.

Methods Participants

The participants were attending a B1 level English for Basic Academic Skills course as part of their degree in Education Sciences. They were second year students who had started university in the 2020/2021 academic year, which meant that they had attended most of their first year online because of the pandemic. In the first semester of the 2021/2022 academic year, while university policies encouraged holding lessons on campus as much as possible, some courses were still being held completely online for the reasons mentioned previously. As regards the English course in particular, the students had been divided into groups based on their level, with 4 groups being offered face-to-face lessons on campus while 8 groups attended online. Unfortunately, due to issues related to Covid-19, two of the on-campus courses had to move to an online modality towards the end of the semester, which meant that some students attended a blended mode where some of the lessons were in person, while others were held online. A total of 115 students participated in the study, of these 87 attended online, 16 in person, and 12 in a blended mode. 110 of the participants were women, which is not unusual for this degree course, with the majority of the students aged 20 to 21.

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 24

Data Collection Tools

The data were collected using an online questionnaire administered at the end of the course. Completion of the survey was voluntary and responses were kept anonymous. The aim was not to assess the course content per se, but rather the way in which the course had been delivered. For this purpose, the questionnaire was divided into macro-sections, each with a series of items which included yes/no, Likert scale, dropdown lists, and open questions. The items were all in Italian to ensure that there was no misunderstanding due to the language. Specifically, in addition to a section on general information (e.g., age, residence, internet connection, devices used) and digital competence, there were items regarding:

• The advantages and disadvantages of the course delivery mode (online or on campus)

• The learning environment (home environment or classroom environment)

• The students’ engagement (e.g., to what extent they interacted with the teacher/their peers, their level of concentration, their interest)

• Their participation preference/style (e.g., their attendance rate, preference for working alone or with others)

• Their perceived impact on their learning skills in general

• Their perceived impact on their language competences

• The challenges met and achievements reached

Some sets of questions varied depending on whether the students had attended the course in person (N=16) or online (N=87). Those students who had attended a blended mode (N=12) were asked to reply to both sets of questions.

For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on the advantages and disadvantages of the course delivery mode, students’ engagement, their perceived impact on their language competences, and their challenges and achievements.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 25

Results

Advantages and disadvantages of the course delivery mode

Among the advantages listed by the students who attended all or part of the course on campus (N=28), 32% of the respondents said it allowed them to experience university life more fully. The same percentage was related to having more interaction with the teacher, while 25% said they interacted more with their classmates, got to know each other better, and that understanding the topics presented in class was easier face-to-face. Only 11% listed having fewer distractions as an advantage and just 4% said attending in person was more motivating. As for the disadvantages, most were related to fear of getting Covid (43%) and finding it annoying to wear a mask (36%). 18% felt uncomfortable when speaking in class, while 11% thought it was more stressful. Finally, 4% found no disadvantages.

Turning to the advantages of attending the course online (N=99), the most popular answers were having easy access to online materials (54%), being able to record the lesson (46%) and manage their time better (41%). 21% said they had more interaction with the teacher, while only 6% said they had more interaction with other students. There was also reference to saving money, with 33% of the respondents listing this as an advantage. Not surprisingly, the greatest disadvantages were related to problems with technology (66%). Another disadvantage was reduced interaction with the teacher and with classmates, which was chosen by 25% and 29% of the students respectively. 16% felt they were socially isolated. Lastly, 9% said there were no disadvantages.

Students’ engagement

Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements related to student engagement using a Likert scale of 1-5 (strongly disagree-disagree- neither agree nor disagree- agreestrongly agree). In particular, the graphs below refer to the percentages of participants who agreed or strongly agreed (4-5) with the statements. As can be seen, over half of the participants who at-

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 26

tended in person were very happy with the quality of the lessons and felt it was easy to engage with the teacher. It is interesting to note that 25% said they missed having class online along with 18% who felt it was difficult to concentrate when they were surrounded by other students, which may imply that they had become accustomed to remote classes.

Student engagement: In person

I AM VERY HAPPY WITH THE QUALITY OF THE LESSONS

IT WAS EASY TO ENGAGE WITH MY FELLOW STUDENTS IN CLASS

IT WAS EASY TO ENGAGE WITH THE INSTRUCTOR IN CLASS

I CAN’T CONCENTRATE IF I’M SURROUNDED BY OTHER STUDENTS

I MISSED HAVING LESSONS ONLINE

As for those who had attended the course online, almost half of the students claimed to be very satisfied with the quality of the lessons. As regards interaction, while 45% thought it was easy to interact with the instructor, a lower percentage (27%) said this applied to interacting with their classmates, which is also much lower than the percentage of agreement on the part of students who attended in class (43%). In fact, 47% of those who attended online said they missed interacting with students face-to-face in class. Concentrating online does not appear to be a problem for students, with 14% agreeing with this statement.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 27

25% 18% 54% 43% 54% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Student engagement: Online

I AM VERY SATISFIED WITH THE QUALITY OF THE ONLINE LESSONS

IT IS EASY TO INTERACT WITH MY FELLOW STUDENTS DURING AN ONLINE LESSON

IT IS EASY TO INTERACT WITH THE INSTRUCTOR DURING AN ONLINE

LESSON

I CANNOT CONCENTRATE WHEN THE LESSON IS LONGER THAN 15 MIN

I MISS THE IN-PERSON INTERACTION WITH OTHER STUDENTS

Perceived impact on language competences

In this section, the participants also used a Likert scale to indicate their level of agreement with the statements provided. As for preparation for the final test, both modalities had similar percentages of agreement (57% on campus, 59% online). Surprisingly, a high percentage of students who had attended online believed the course had helped them improve their interaction skills compared to those who attended on campus (46% to 39%). The percentage is also higher for the other skills, including improvement of language competence in general.

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 28

47% 14% 45% 27% 47% 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% 50%

Impact on language competences: in person

PREPARATION FOR FINAL TEST

IMPROVEMENT OF INTERACTION SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF WRITING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF READING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF SPEAKING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF LANGUAGE COMPETENCES IN GENERAL

Impact on language competences: Online

PREPARATION FOR FINAL TEST

IMPROVEMENT OF INTERACTION SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF WRITING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF READING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF SPEAKING SKILLS

IMPROVEMENT OF LANGUAGE COMPETENCES IN GENERAL

Challenges and achievements

The last section allowed participants to specify the challenges they had met as well as the achievements they had reached. Among the challenges listed by the on-campus students, there is difficulty understanding the teacher (probably because masks were mandatory) and improving their listening skills, getting used to physically going back to class, and interacting with new people. On the oth-

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 29

36% 36% 39% 46% 39% 57% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

57% 41% 61% 55% 46% 59% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

er hand, they saw managing to interact with the teacher and their classmates as an achievement, as well as being able to focus more and putting more effort into improving their skills.

Some students who attended online also found understanding and interacting with the teacher difficult because of the course delivery mode. In fact, they pointed out that trying to learn a language without having the physical presence of a teacher is quite challenging. Many students said it was difficult to speak with their webcams on, which is one of the main reasons why many of them did not turn them on even when they were prompted to do so. A lack of socialization was also seen as a great challenge. As for the achievements, managing to work on their own and focusing more were mentioned as was overcoming shyness.

Final reflections

The current study presents some limitations, namely the relatively small sample size and the fact that the on-campus, online, and blended groups were different sizes. Nevertheless, the findings provide some interesting insights into the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on students’ attitudes and beliefs about online and in class learning.

In general, students who attended in person seemed happy to be back on campus although there was still some hesitancy. They tended to participate more actively, and there was more interaction with the teachers and with other students.

Students who attended online generally seemed more satisfied with the delivery mode, with some of them expressing the wish to continue attending remotely even after restrictions have been lifted. Some students prefer this delivery mode because they seem to be afraid to interact and they do not seem ready to leave the comfort of their own homes yet.

Turning to language competences, the percentage of online students who report having improved these is higher than that of those who attended in person. However, no generalizations can be made regarding this so far, as it was a self-evaluation. These answers will be

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 30

compared to the results of the test they took at the end of the course to verify whether, or not, there is a correlation between course modality and improvement of language competences.

It is clear that Covid-19 has accelerated a digital revolution and has heightened the necessity to optimize teaching and learning in similar contexts in the future. In line with other studies, these research findings underline the importance of providing innovative teaching materials in order to increase student engagement and motivation regardless of the teaching delivery mode.

References

Almuraqab, N. A. (2020). Shall Universities at the UAE Continue Distance Learning After the COVID-19 Pandemic? Revealing Students’ Perspective, International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology (IJARET), 11(5), 2020, pp. 226-233.

Coman, C., Gabriel Tîru, L., Mesesan-Schmitz, L., Stanciu; C., & Bularca, M.C. (2020), Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during the Coronavirus Pandemic: Students’ Perspective. Sustainability, 12, 10367, 2-24.

Cranfield, D.J., Tick, A., Venter, I.M., Blignaut, R.J., & Renaud, K. (2021). Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning during COVID-19—A Comparative Study. Educ. Sci., 11, 403.

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning, Educational Review, 27 March 2020. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Means, B., & Neisler, J. (2021). Teaching and learning in the time of COVID: The student perspective. Online Learning, 25(1), 8-27.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 31

CHAPTER 2

How does feedback work in an online exam preparatory course? Insights from a teacher research project

Anna Soltyska

Introduction

This article provides an overview of a teacher research project conducted in an English for Academic Purposes course for prospective IELTS test-takers and focused on the development and assessment of writing. The aim was to learn if and how feedback in online contexts can be provided efficiently and observe to what extent online feedback can meet students’ divergent needs. The author reports on preliminary findings from a small-scale classroom study which might offer insight into the nature of developing writing skills via teacher’s feedback in an online exam preparation course attended by a highly heterogenous studentship.

Background of the project

The project in question was conducted between April 2021 and January 2022 in the course “English for IELTS and beyond (B2-C1)” offered at the University Language Centre of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Between the summer 2020 and winter 2021/22 the ersatz edition of the course was offered exclusively online 1 due to the closure of German universities during the Covid-19 pandemic

1 Before the onset of the pandemic the course had been taught in a blended learning format whereby the teacher-students interaction would take place in person and be complemented with self-study phases via Moodle (for more information on this open-source Learning Management System see https://moodle.org).

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 33

In line with major principles of teacher research, the project was a systematic inquiry of a self-reflective character, conducted by the teacher on the basis of the students’ work, in order to improve their awareness of implications of their work and enhance their teaching and assessment practices, thus students’ learning (see Borg 2017:165). It emerged from experiences collected by the author during emergency remote teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al., 2020) and is rooted in a structured reflection on the makeshift version of the course, which concerned, in particular, opportunities and challenges related to providing feedback in the digital setting.

Focus of the project and types of feedback provided

The project focused on the role of feedback in the development and assessment of writing as measured by IELTS Academic Writing Task

2. A typical exam task requires test-takers to write an argumentative essay of at least 250 words in response to a statement or premise. Writers should discuss viewpoints presented in the topic and provide relevant examples from their own knowledge and experience to justify claims. Within the IELTS exam the essay writing is tested within a time limit (40 minutes) by means of handwritten submissions with no aids such as dictionaries, thesauri and spellcheckers.

In the project, students’ writing performance was assessed on the basis of essays composed in an unsupervised way, typed and submitted via Moodle. These divergent features of the writing development and assessment process within the course and in the actual IELTS testing situation may have significant implications for the generalisability of some project results for offline contexts. Nevertheless, they were unavoidable under the pandemic circumstances and ERT.

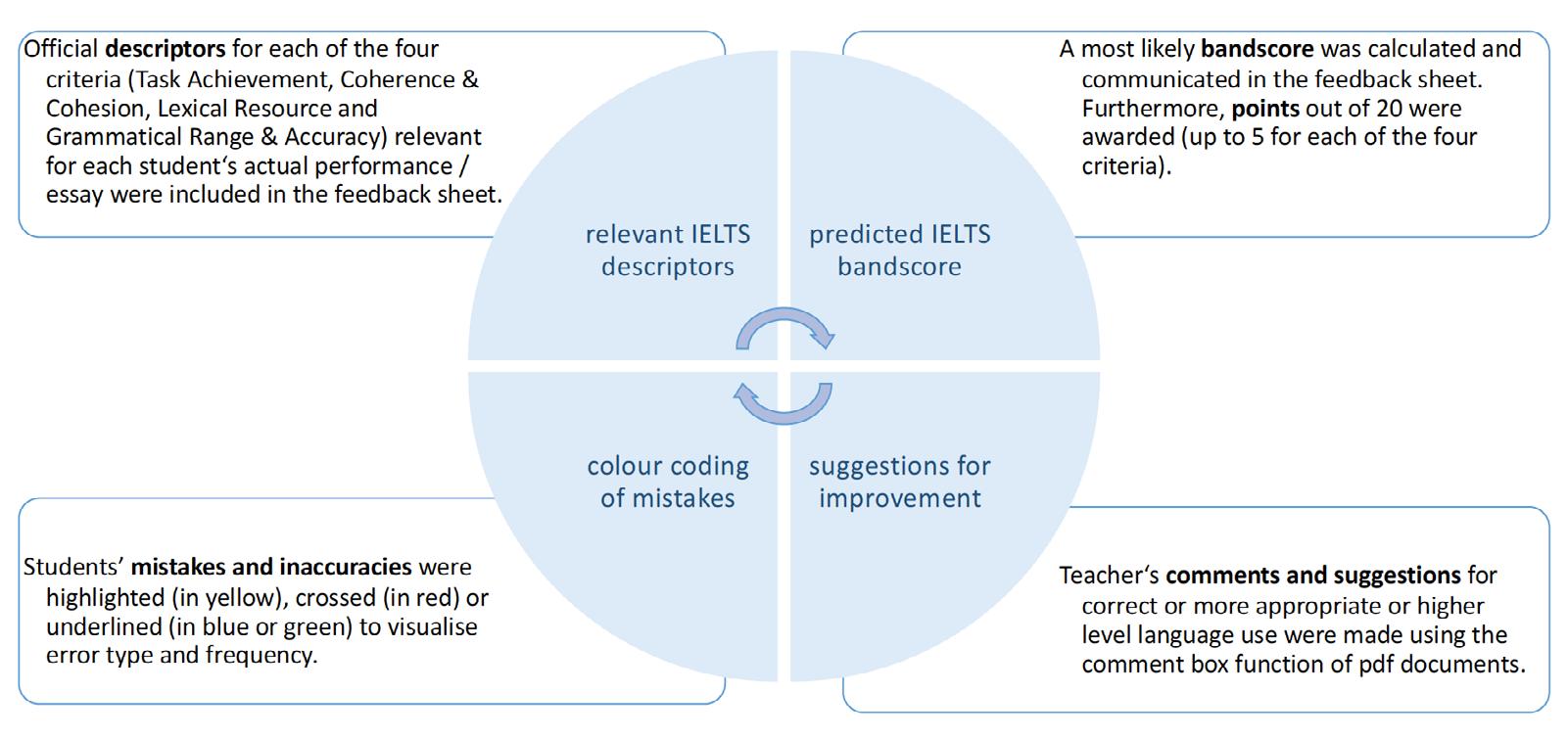

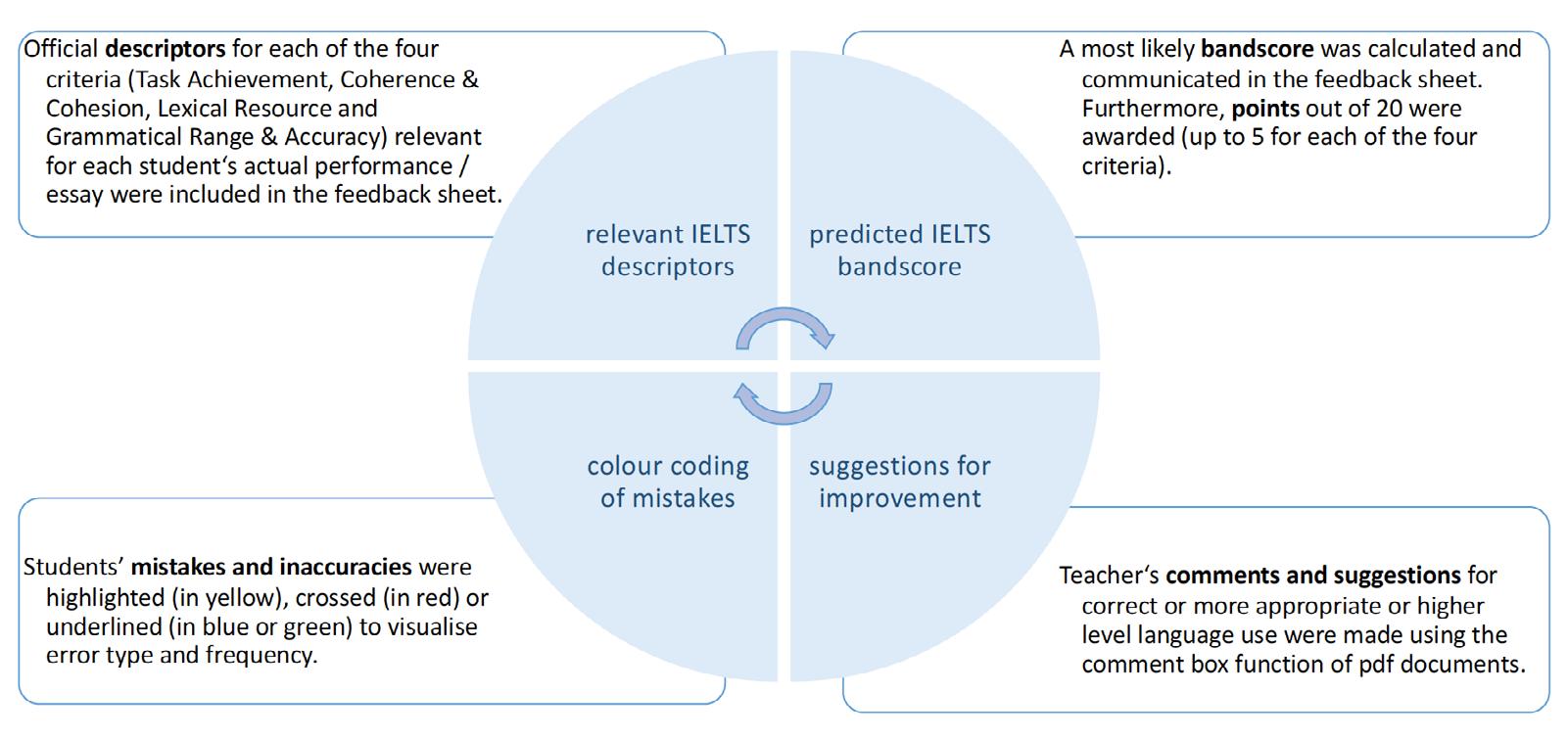

Each term, six essay tasks were set and collected via Moodle. Students had one week to write each text and the teacher had approximately four days to assess submissions and announce the results and comments via Moodle. Fig. 1 summarises the type of feedback provided on each submission.

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 34

3. Participants in the study

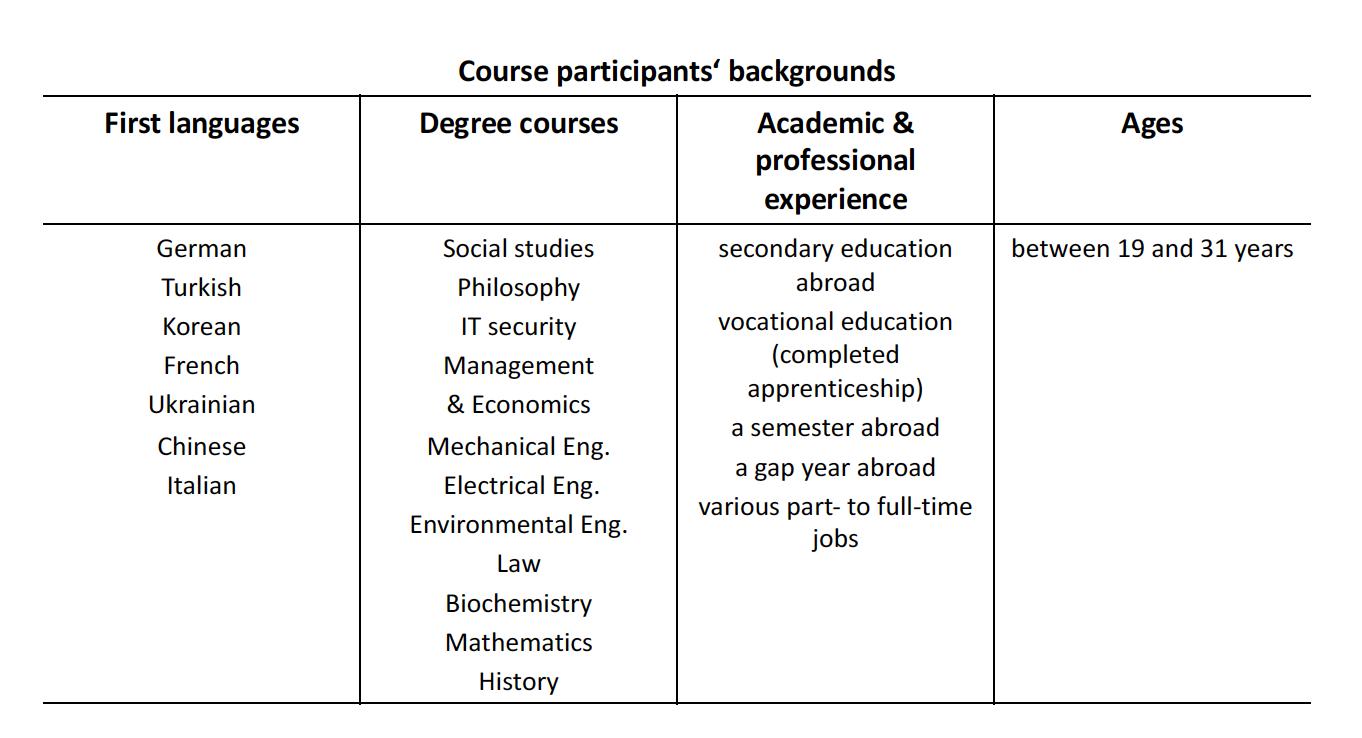

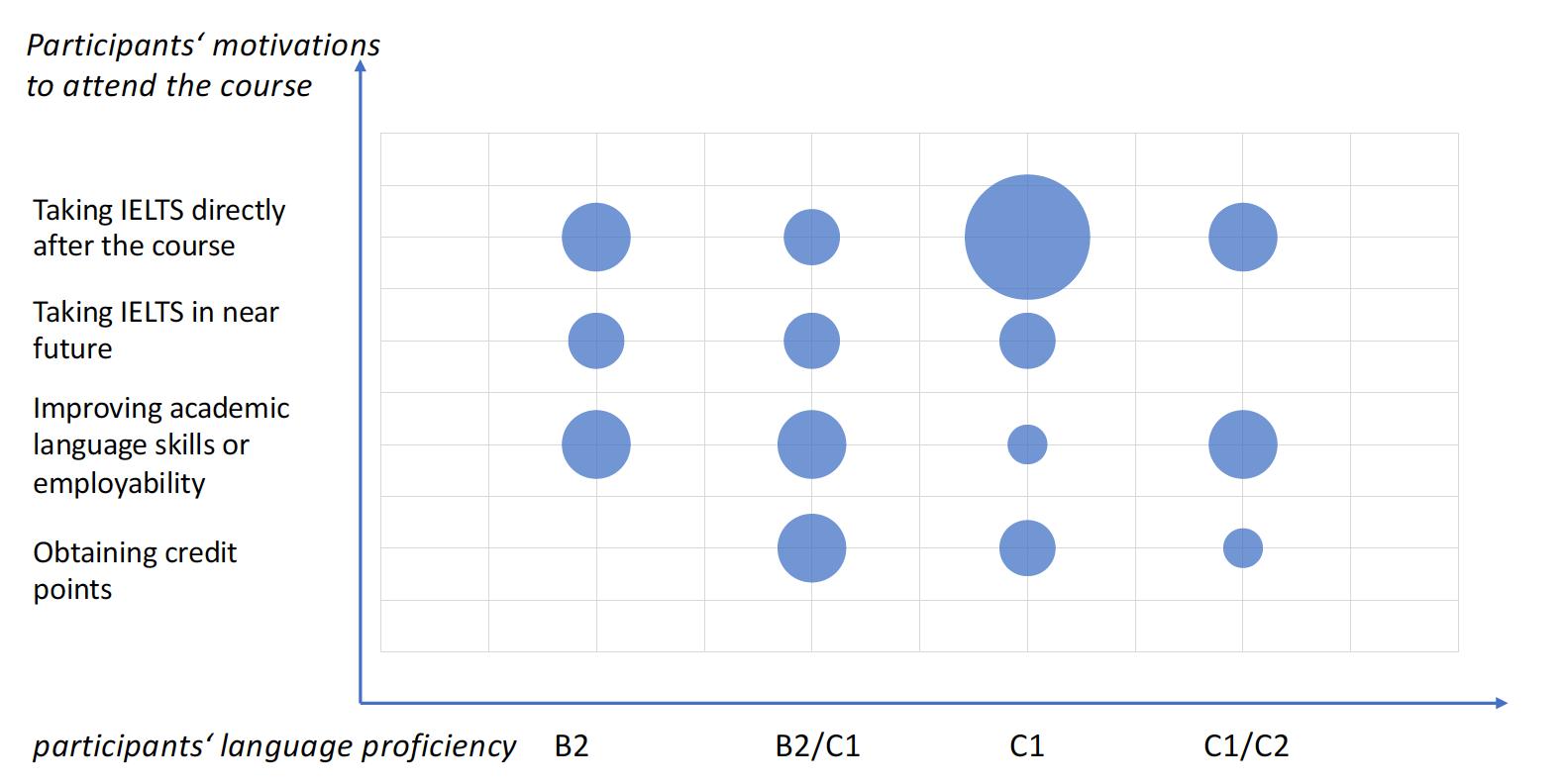

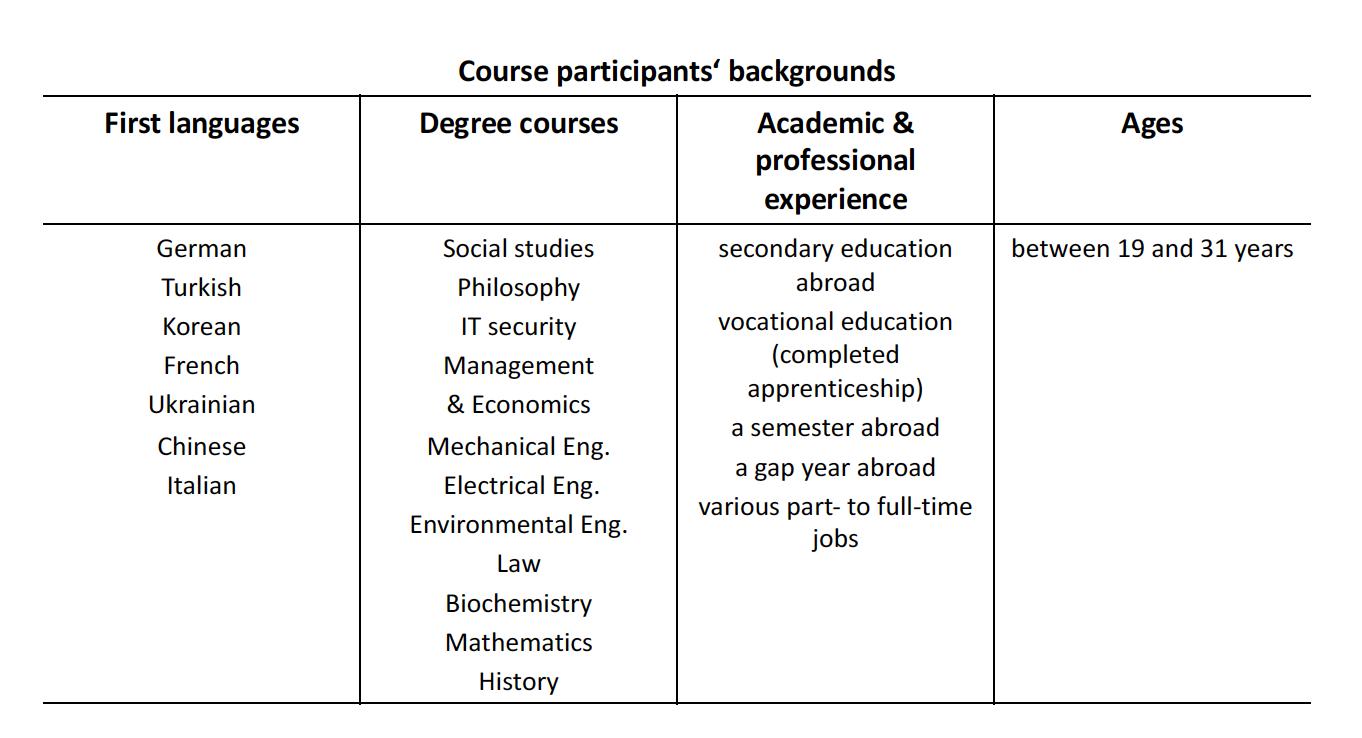

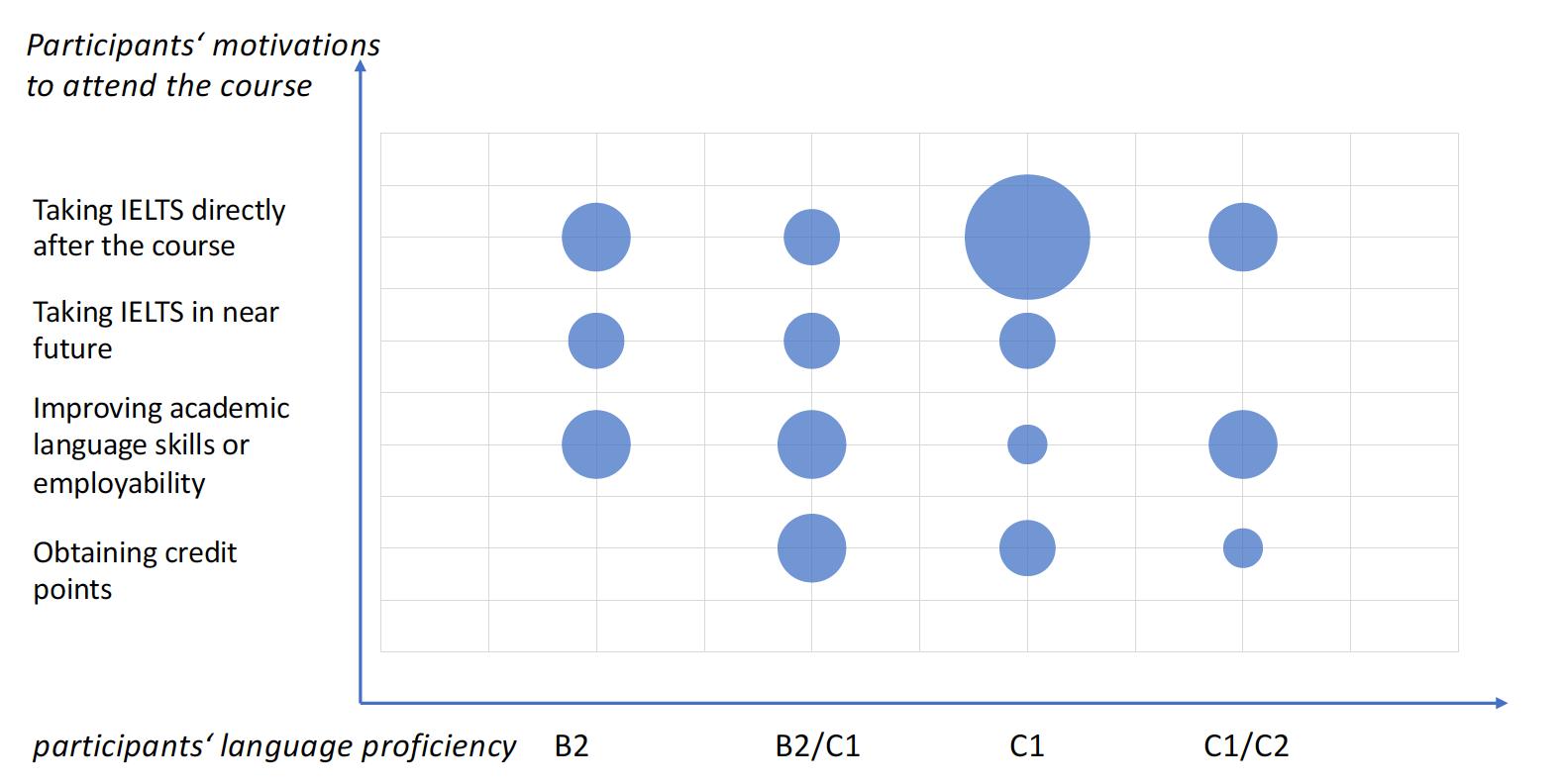

38 students participated in the study (18 in the summer 2021 and 20 in the winter 2021/2022). The participants were highly heterogeneous considering their L1, degree programmes, academic and professional experience, and ages. Their English proficiency levels varied from B2 to C1+ and they attended the course for various purposes. Fig. 2 provides the overview of diverse studentship in the two cohorts based on the data analysis from numerous sources 2 .

2 Students’ proficiency levels were established on the basis of an in-house calibrated placement test (C-test); the information on students’ degree programmes and ages was taken from the university study management system; the purpose of taking the course and students’ L1 and academic and professional experience are self-reported. All participants consented to their data and performance samples being collected and processed for the purpose of the TR project.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 35

Fig. 1 Overview of the four components of teacher’s feedback on students’ writing

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 36

Fig. 2 Course participants’ backgrounds

Fig. 3 Overview of the participants of the project (size of dots denote numbers of participants at a given proficiency level attending the course for a given purpose).

Methodology

Participants’ opinions on the feedback provided were collected in an online survey (n=38). The questionnaire, comprising 7 closed items (multiple and single choice items, including Likert scale responses) was created in line with the guidelines provided by Dörnyei and Taguchi (2010) and Dunn (2013) and delivered via Moodle in the last week of each course.

Students’ essays (n=145) were assessed by means of the grading rubric based on publicly available IELTS essay bandscore descriptors 3 . The results were analysed in terms of mean overall scores for each essay topic, mean scores for each of the four criteria as well as improvement (or its absence) of selected aspects of writing of each student. Qualitative analysis of essay results comprised an overview of common errors and evidence for individual achievement.

The teacher’s reflective journal included information on assessment and feedbacking process in the online setting.

Preliminary findings

In the students’ view, submitting essays for improvement and assessment proved not only the most enjoyed course task at the time of ERT (according to 92% of respondents), but was also perceived as the activity which helped most in language learning (83%). When working on subsequent assignments all students admitted referring to the feedback previously received. Moreover, they all found the feedback “very” or “quite” useful, whereby teacher’s suggestions for more appropriate or correct use were named as most helpful (over 90% of responses) irrespective of students’ level and purpose of attending the course. This type of most useful feedback was closely followed by color-coded marking of mistakes.

The quantitative analysis of students’ overall scores and score trends per criterion and qualitative study of their essays confirm

3 For details of the grading rubric see https://takeielts.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/ielts_task_2_writing_band_descriptors.pdf.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 37

some noticeable overall improvement in writing skills.

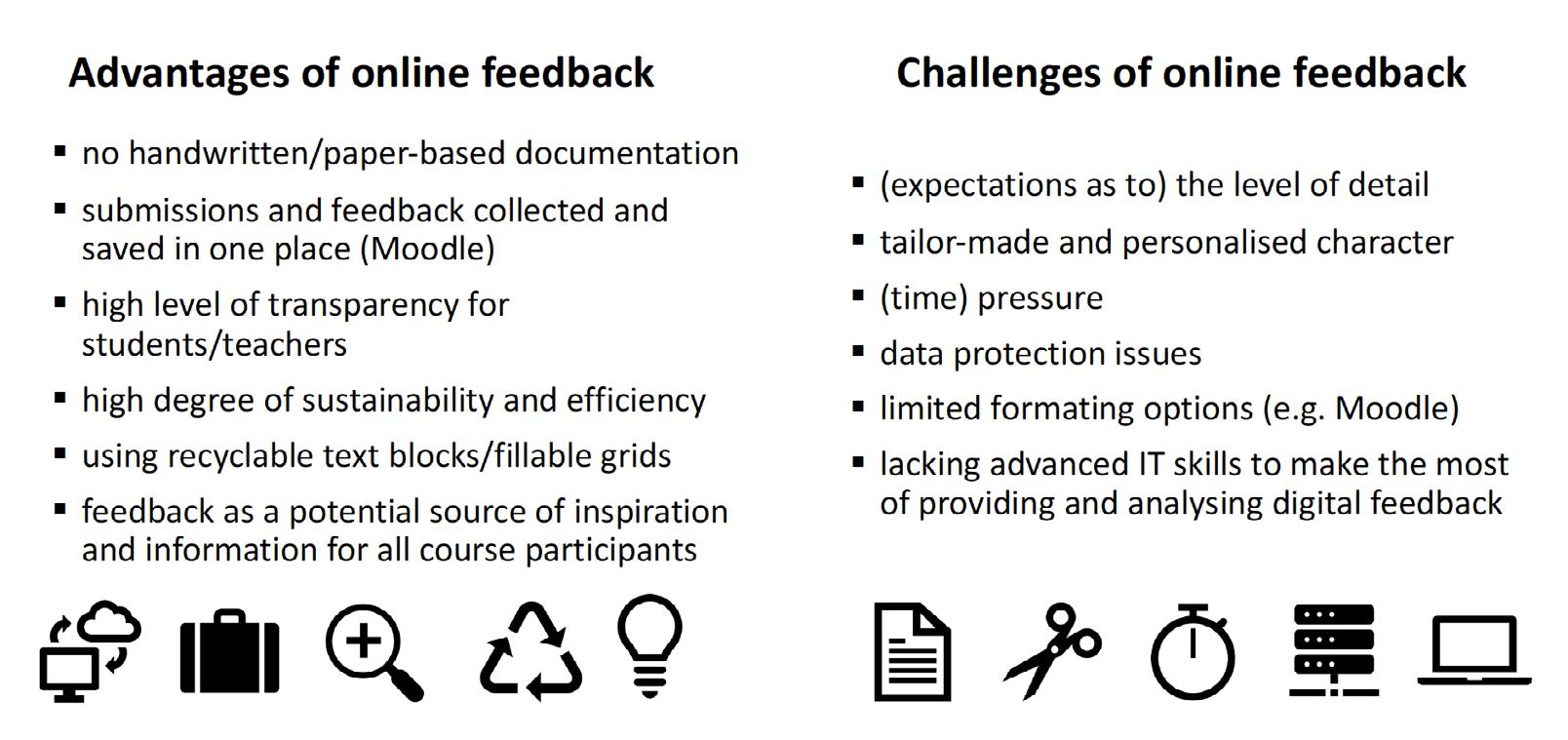

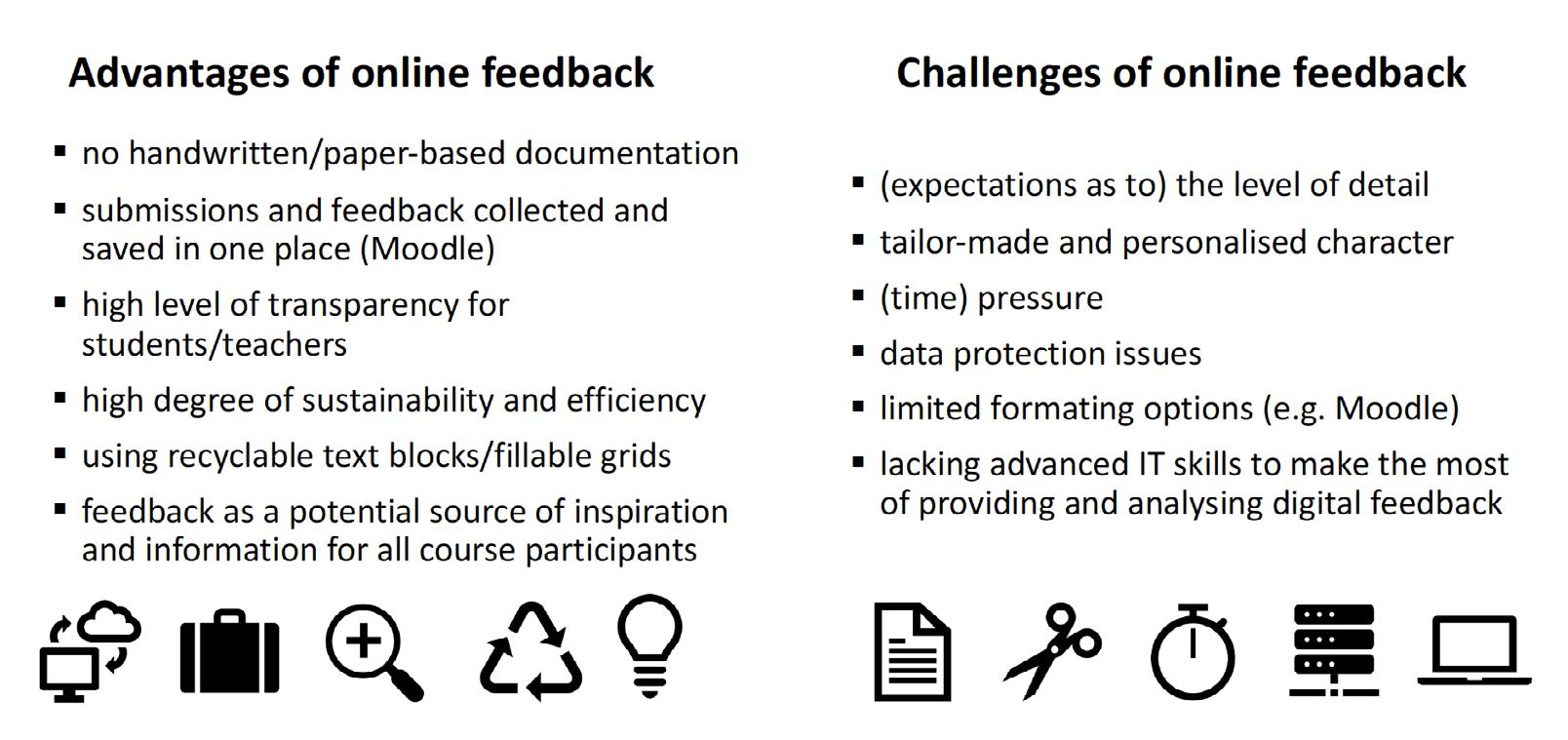

The teacher’s views on providing feedback online as per their reflective journal were balanced and included both benefits and drawbacks. This subjective perspective is summarised in Fig. 4.

Conclusion

The study reinforces the view that “learners tend to appreciate comments that feed forward to another task and inform them about the expectations of the educator with regard to the quality of that task” (Henderson et al, 2019, quoting Hendry et al, 2016). Despite the heterogeneity of their profiles, overall the participants were satisfied with the feedback, which might have contributed to the improvement of their writing skills. However, as “there is no single model that will guarantee feedback to be useful and effective for all students and teachers” (Henderson et al, 2019 quoting Sadler 2010 – additions in italics from the author), the findings from this small-scale study may not apply elsewhere.

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 38

Fig. 4: Teacher’s views on providing feedback in an online setting

Further training in providing feedback digitally and establishing internal rules on reacting to students’ writing could contribute to a more positive feedbacking experience also for teachers.

References

Borg, S. (2017). Twelve tips for doing teacher research. University of Sydney Papers in TESOL , 12, 163-185.

Dörnyei, Z. & Taguchi, T. (2010) Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration and processing. New York: Routledge.

Dunn, D.S. (2013). Research methods for social psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Henderson, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Phillips, M., Molloy, E. & Mahoney, P. (2021). The usefulness of feedback. Active Learning in Higher Education 2021, Vol. 22(3) 229-243. https:// doi.org/10.1177%2F1469787419872393

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educational Review, 27 March 2020. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 39

CHAPTER 3

Following the footprints of online ESP learning: action research

Amalia Babayan

Introduction

Digital experts specify that when streamlining high quality online education, the only significant difference should be the way that the classes are delivered (Monroe, 2010). In 2020 we were granted a unique chance, due to the Covid 19 pandemic, to test the effectiveness of learning management systems. In our case, we had an opportunity to test whether Moodle proved reliable and valid (Jeong, 2017) for teachers and students. Language teaching practice conducted entirely online, followed by the return to face-to-face classes after three semesters of isolation, had raised questions that required better understanding of the working process.

The project

The action research we conducted was performed in two phases: during the pandemic period (May-June 2020) and the comeback phase (September-November 2021). The participants in the study were II, III and IV-year Bachelor’s program students of the Faculty of International Relations of YSU and the professors teaching them: 35 students and 12 professors in the first phase and 33 students and 16 professors in the second.

The frequency of both online and offline classes was three times a week with double forty-minute sessions, with 15-19 students in each group. In both phases the standard academic curricula of ESP teaching at corresponding levels was delivered, which implied a variety of language learning activities ranging from reading, material dis-

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 41

cussions, peer work and role-play to written tasks, press reports and slide-show topical presentations. Student participation was mandatory, and lessons were conducted in standard synchronous mode.

The aim of the first phase of the research project was to explore the extent to which online platforms allow the creation of an integrated and fully functioning ESP classroom; the influence of socio-psychological aspects and the inclusion or omission of essential ESP teaching components. In light of the findings of the first phase, the second phase of the research pursued one goal: to find out the factual working differences between the online and offline language teaching as assessed by students and professors.

Methodology

The methodology encompassed collecting data from field notes during and after lessons, questionnaires, interviews, analysis of assignment feedback, student assessments and statistical interpretation. Completing questionnaires or participating in interviews were conducted exclusively on a voluntary basis and questionnaires were anonymous to ensure objectivity. There was no rigid time frame for the interviews, to allow a natural flow of communication.

For the second phase, separate questionnaires were designed for the professors and students containing 5 and 10 items respectively. They consisted of multiple-choice questions, Yes/No questions and questions to be answered on a 0-5 scale. The findings were informed by all the data mentioned above, but were mainly derived from the questionnaire and interview responses.

Findings and Discussion

The findings of the first phase indicate that the multifunctional instructional tool kit provided by the LMA Moodle platform helps to create a comprehensive and well-organized curriculum that works effectively for the teaching and learning of listening, reading and writing competences. However, the development of ESP communicative skills leaves much to be desired. Due to technological lim-

SECTION 1 CLASSROOMS IN TRANSITION 42

itations, such important language learning activities like ad hoc simulations of negotiations and interviews, team-work discussions and role-play are not practically feasible within the limits of the academic time frame.

The restricted use of humour and the lack of body language result in more formal onscreen contact, which, in its turn, complicates the instructor’s feedback on students’ speaking performance. The challenges posed to the teacher’s feedback are often caused by technical difficulties , the excessive exposure to online public attention, which students are not always comfortable with, and the inability to use body language and extra-lingual means to the full for making or inviting corrections. Hence, teacher-student contact during online classes tends to be comparatively formal.

The Moodle platform works well for making presentations, delivering talks and speeches. However, the type of teamwork where students collaborate shoulder-to-shoulder, where there is a ‘wireless’ bioenergy and synergy, an overlapping give-and-take of ideas and enthusiasm is missing during online classes.

The findings of the second phase complemented the results of the first-phase. When rating the efficiency of online and offline teaching, 78% of the students (26) preferred offline learning, and only 24% (8) considered online education as an option. Consequently, the enthusiasm for coming back to offline classes is high among both students and professors: 33 against 24 (students) and 14 against 2 (professors). In response to the question: ‘What is it that appeals to you in offline education?’ 28 responses indicate ‘Contacts and communications’, 27 – ‘Learning and education’, and 23 – ‘Friends’ and 19 - ‘Professors’.

The format of this paper allows a brief introduction to the study. In future publications we will present a detailed analysis of the students’ responses, as well as discussion of the development of students’ classroom skills, their attendance, homework performance and feedback. We will also explore the professors’ assessments of the organization of the academic process in the online/offline fora.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 43

Conclusion

ESP online teaching and learning is, in many aspects, beneficial, although it proves lacking in the area of communicative skills. Nevertheless, with further advanced technological development, the LMA has the potential to become a highly effective learning platform for teaching and learning ESP. The research findings also indicate that live human communication and a social environment stand out as a crucial factor in the language education process as assessed by students and professors alike.

References

Jeong Kyeong-Ouk. 2017. ‘The Use of Moodle to Enrich Flipped Learning for English as a Foreign Language Education’. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, Vol. 95, No. 18, 4845-4852.

Monroe R. 2010. ‘First Decade High Impact’. Paper presented at the CASCON conference, Toronto Ontario Canada, November 2010.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 44

SECTION 2 Beyond the classroom: Maximising learning opportunities

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 45

Using Moodle increases older adult language learners’ autonomy and motivation

Jodi Wainwright

Introduction

When older adult learners are supported and encouraged by participatory and collaborative activities that are particularly addressing their interests and needs, their motivation is increased. In return, this also promotes their understanding to learn how to learn by themselves. Moodle gives these learners a context in which they can learn with and from each other, developing their autonomy collectively. Moodle gives the possibility of bringing more diverse and authentic materials into the classroom to practise listening skills and to enhance cultural awareness. Such materials are especially effective in helping learners work on their own and at their own pace, thus fostering individualised learning, as well as skills related to self-reflection, autonomy and independence. The findings from this study in France show how the use of Moodle can increase autonomy and motivation for older adult language learners.

The use of technology in language learning is associated with autonomous learning which enables learners to continue their learning beyond the classroom. Blended learning may have a beneficial effect on the learner by offering a different kind of support: the opportunity to work at a time and place according to individual preferences and needs. Furthermore, the act of learning how to use technology can add to a sense of achievement for older adults (Lee et al., 2013). Autonomy is not only about giving free choices to the learners to choose what and how they learn something or transferring all control and

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 47

CHAPTER 4

responsibilities in learning to the learners, but it is also about how to teach them to use their own capacity to learn effectively.

Digital learning, such as using Moodle, provides enhanced motivation for learners, keeping them interested and focused on the learning content because they are also interested in engaging with the technology and technologically mediated materials. Benefits include being able to access authentic language learning inputs at any time, being able to follow a programme of learning in one’s own time, being able to interact with learning colleagues and peers in all parts of the world at any time, and being able to constantly assess and reassess one’s learning successes, strengths and weaknesses. As Carrier (2017) says, digital learning puts learners in control of their own learning. By sharing knowledge and expertise and supporting each other in a Community of Practice, as Wenger-Trayner and Wenger (2015) describe, learners develop a shared collection of resources and this sense of ownership leads to increased motivation.

Research Questions

The results reported in this chapter are part of a doctoral research study entitled “When older adults use Moodle to learn languages…” the main research questions for the study were:

• What are the challenges for older adults using Moodle to learn languages?

• What are the rewards for older adults using Moodle to learn languages?

Methodology

Using a qualitative case study methodology, learners were interviewed about their use of Moodle to learn English. The interviews were supplemented by data from the Moodle platform in order to fully analyse learners’ perceptions of their use of Moodle with the aim of answering the research questions. Initial interviews were carried out with twenty-two learners and five of these learners then

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 48

took part in follow-up stimulated recall interviews. Using reflexive thematic analysis, the initial interviews were analysed using inductive thematic analysis and the follow-up interviews were analysed using deductive thematic analysis with the codes identified from the initial interviews.

Results

Learners appreciate the flexibility that Moodle provides in as much that “we can work at any time we want, for however long we want” and “we can exchange with other learners at any time” (L*4). L*9 also said “we can access it all the time” and “that’s the advantage of Moodle, you can work on it whenever you want”. L*20 said “it’s accessible when you want” and L*21 “it is good to use at home”. This flexibility is also evident in comments such as “I would have worked at home less if I hadn’t had Moodle” (L*17).

Using Moodle gives learners time and space to reflect on their participation and learning, L*4 said “we have more time, we think more”. L*15 said, “I take more time to do things” and L*18 said, “we have time to do our lessons, time to do our homework quietly”. L*4 described how through using Moodle “we learn to fend for ourselves because we have no-one in front of us to answer our questions as in class” and “it’s great when you’re sick you can always learn at home”. L*19 said that in order to use Moodle “you have to be autonomous” and “we can repeat at our own pace… this progression at one’s own pace, it can be an asset”. L*9 explained how using Moodle “enables me to work at home… without support”.

Learners find using Moodle motivating, with comments such as, “Moodle encouraged me to practice” (L*9) and “it made me want to come back more to learn English” (L*10). L*3 said “I am more eager to learn and improve myself” and “when I watch the videos, it makes me try to speak for myself”. L*8 said “it energises the learning” and L*13 said “it’s rewarding”. L*17 described how using Moodle, “motivated me to do my personal work at home”. L*11 said “it enabled me to see the corrections, to keep me informed. That was a

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 49

very positive thing for me because it kept me going”. For L*19, using Moodle “I get the feeling that it encourages me to try to do better”.

Conclusions

The increasing use of technologies in education allows tailoring of learning experiences to individual learners, to respond to learner-driven choices about where, what and how learning occurs. Moodle allows learners to manage their learning and promotes a learner-centred environment. Learner-centredness embraces the notion that learners have agency over their learning. Learners have a sense of agency when they feel in control of things that happen around them; when they feel they can influence events.

Having agency means that learners develop aspirations. Participating in a social learning space reflects both the aspiration to gain some new capability and the expectation that it will contribute to a difference that matters. The use of Moodle can assist older adult language learners to use digital technologies, increases motivation and facilitates autonomy. Being autonomous helps learners to develop the awareness, knowledge and skills that they need in order to be able and willing to take control of their own learning.

References

Carrier, M. (2017). Introduction to Digital Learning. In M. Carrier, R. Damerow, & K. Bailey (Eds.), Digital Language Learning and Teaching (pp. 1–10).

Lee, G. Y., Yip, C. C., Yu, E. C., & Man, D. W. (2013). Evaluation of a computer-assisted errorless learning-based memory training program for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease in Hong Kong: a pilot study. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 8, 623–633. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S45726

Wenger-Trayner, B., & Wenger, E. (2015). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. http://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 50

CHAPTER 5

The timeliness of written corrective feedback in a classroom WhatsApp group: A comparison of two feedback modalities and learners’ perceptions

Bridget Murphy

Introduction

Corrective feedback (CF) facilitates language learning, yet when to give feedback in the instructional sequence remains up for discussion among teachers and researchers. Broadly speaking, oral CF in face-to-face (FTF) classrooms can be provided at two times: during a communicative task (immediate corrective feedback, or ICF) or after a communicative task takes place (delayed corrective feedback, or DCF). From a theoretical perspective, second language acquisition seems to support immediate correction because such oral feedback develops communicative competence (Li, 2018). From a pedagogical perspective, teacher training manuals recommend delayed correction since ICF might disrupt fluency and embarrass learners (Harmer, 2012). These perspectives stem from the FTF classroom setting, but do they still hold true in other educational contexts such as mobile-instant messaging (MIM)?

Teachers increasingly use MIM applications like WhatsApp on mobile devices to encourage language learning and the practice of communicative skills beyond the classroom (Benson & Reinders, 2011; Kukulska-Hulme & Shield, 2008). The permanency of chat messages makes MIM applications useful feedback platforms while students complete communicative tasks (Andujar, 2022). As students can read messages in any order and at any time, the concepts of “immediate” and “delayed” might be different in this type

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 51

of classroom context. For this reason, the present study looked at two CF modalities provided through WhatsApp and how these modalities differ in terms of students’ response rate, self-repair success rate, and perceptions.

Methodology

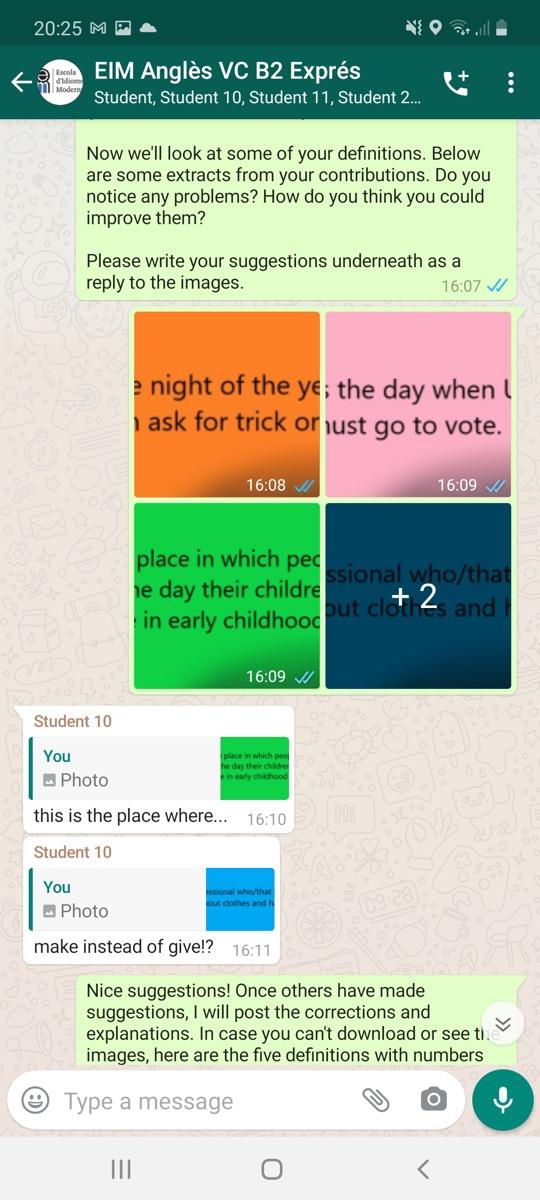

Study participants (aged 19 to 48) were part of an English as a Foreign Language course (CEFR level B2) at a fee-paying university language school in Barcelona, Spain. The 10-week blended course consisted of 20 contact hours through Zoom and 20 hours of independent guided learning activities. After students signed consent forms, the teacher created the WhatsApp group with the researcher acting as task facilitator and CF provider. Ten students participated in the chat and completed the subsequent interviews and questionnaires.

Students were given five communicative tasks over five weeks to complete in the chat. All tasks were based around topics in the students’ coursebook and elicited specific target language (TL) items that students learned in class on Monday mornings. The first task served as an introductory task, and the next four were interventional, alternating between drill-like grammar exercises and open-ended prompts. Tasks were given to students via the WhatsApp group on Monday afternoon and continued through Friday morning.

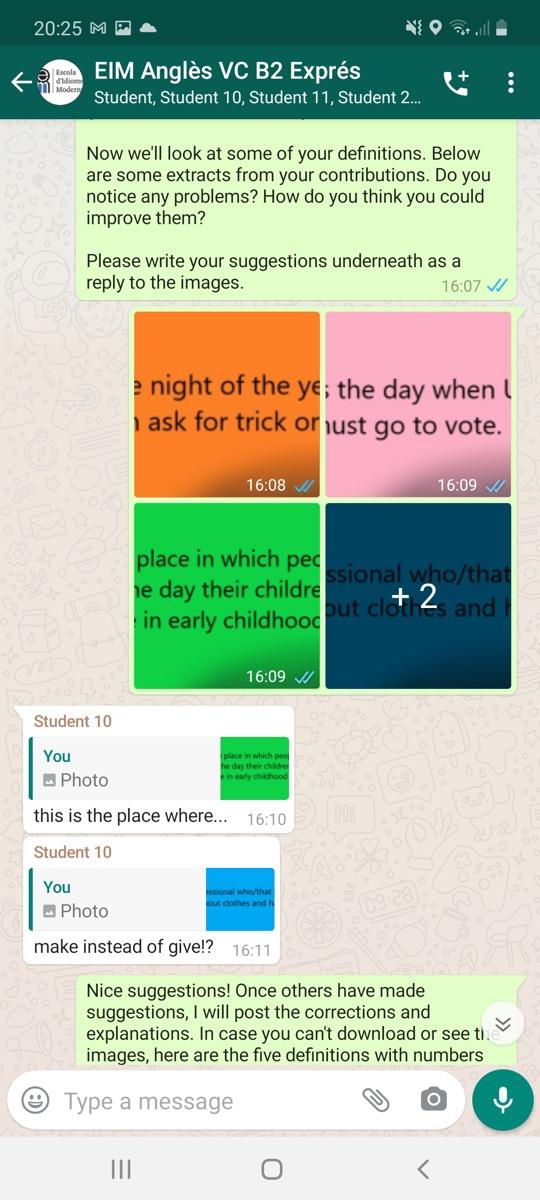

For the first two weeks of the intervention, students received DCF given on Friday afternoon as a language-based activity in which students were invited to correct five selected errors. See Figure 1 below for an example.

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 52

For the last two weeks, students received ICF within 24 hours of error commission. Students repaired their own errors following the researcher’s multi-step feedback procedure including two prompts and a recast. The researcher (1) resent a student’s erroneous utterance to the chat with a thinking emoji to the right of the error, (2) asked a question or gave a metalinguistic clue, and (3) gave a recast (see Figures 2 and 3 below).

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 53

Figure 1. Screenshot of delayed corrective feedback language-based activity

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 54 prompt (thinking emoji) successful repair positive feedback no repair prompt (question or metalinguistic clue)

Errors were selected based on a set of predetermined criteria in order of importance developed by the researcher and teacher: (1) TL items, (2) errors causing breakdowns in understanding, (3) recurrent errors, and (4) language not appropriate for a B2 level.

Students’ opinions of the CF modalities were collected via semi-structured interviews over Zoom and a questionnaire using Google forms.

Results and discussion

The chat produced 623 messages over 33 days. Student participation varied greatly, but overall students liked the WhatsApp group and the CF they received.

Regarding response and success rates, more students responded to CF when it was given immediately during the tasks. Participation in the DCF activities on Friday afternoons was very low when some students reported wanting to disconnect from their phones. Students were also more successful with error correction when given immediate feedback, especially after receiving a second prompt.

Overall students (n=8) preferred ICF for several reasons. S3 felt that ICF “stimulate[d] the interaction” in the chat, and two students felt that it allowed for daily language instruction. As S7 said, the ICF was “another form to make you connect and not disconnect from Monday to Saturday.” Students also liked that ICF alerted them to errors soon after they were made, which motivated them more to self-repair. S2 mentioned, “it was very useful to have the feedback like at the moment, and not wait like till the end of the week,” because, as S5 clarified, “you don’t remember what you said in the beginning of the week.”

Only two students preferred DCF reasoning that there was no pressure to respond immediately, and they could review other students’ messages before sending their own.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 55

Conclusions and pedagogical implications

Timeliness of CF is “of theoretical and pedagogical significance” and “a topic that has received little attention” (Li, 2018, p. 1). For practitioners, giving CF through WhatsApp can be successful especially if feedback is immediate while students interact in communicative tasks and are repeatedly prompted to self-correct.

The present study highlights several factors for practitioners to consider when providing feedback in a WhatsApp chat. First, age might play a factor in deciding to give CF through WhatsApp. More research is needed on this topic, but as the present study showed, students older than 28 had mixed preferences regarding CF timing, and the two oldest students voiced the most concern about the use of WhatsApp for language learning. In addition, two students expressed wanting positive feedback, not only corrective. This is simple to do using emojis and GIFs on a WhatsApp keyboard. In the present study, students also reported wanting more spontaneous interactivity facilitated by voice or video messages. Teachers can make use of the multi-modal features of WhatsApp to help students practice communicative skills other than writing. As a suggestion, teachers should avoid giving tasks or DCF on Fridays when students are less likely to respond. Most importantly, it remains to be seen if giving ICF is truly sustainable. The researcher in this study found it very time consuming to give immediate CF, especially with a multi-step CF procedure. Peer feedback might ease this workload as well as setting specific timetables for teacher CF provision through WhatsApp.

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 56

References

Andujar, A. (2022). Mobile instant messaging for ELT. ELT Journal .

https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccac004

Benson, P., & Reinders, H. (Eds.). (2011). Beyond the Language Classroom. Palgrave Macmillan.

Harmer, J. (2012). Teacher knowledge: Core concepts in English language teaching. Pearson Longman.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Shield, L. (2008). An overview of mobile assisted language learning: From content delivery to supported collaboration and interaction. ReCALL , 20 (3), 271–289.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344008000335

Li, S. (2018). What is the ideal time to provide corrective feedback? Replication of Li, Zhu & Ellis (2016) and Arroyo & Yilmaz (2018). Language Teaching, 53(1), 96–108. https://doi. org/10.1017/s026144481800040x

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 57

Teacher-talk and Facebook: An enquiry into pedagogical and methodological expectations of GenZ EFL learners in Germany

Kevin F. Gerigk

Introduction

This paper looks into the pedagogical and methodological expectations of Generation Z (GenZ) EFL learners in secondary and tertiary education in Germany. First, GenZ is discussed and a rationale for my research questions is provided. Then, I describe the context and methods used in this study before I present and discuss my results.

Generation Z: local and supralocal context

GenZ is defined as the cohort born between 2000 and 2011, currently inhabiting late secondary or tertiary educational sectors. They have grown up in a fully digitalised world (Chicioreanu & Amza, 2018), which means that they are used to constant exposure to visual stimuli and information. It may, therefore, be suggested that this cohort has an inherent need for the inclusion of technology and social media in education. In addition, Kinash et al. (2013) suggest that this exposure to stimuli may have altered GenZ’s brain structure, leading to reduced attention span, which may have impacted their ability to focus on teacher-centred lessons. Furthermore, Jensen (2019) suggests that due to this cohort’s connectedness, they are diverse and tolerant, preferring collaboration over competition. A study conducted by the British Council (2019) in Germany further suggests that GenZ in Germany suffer from high levels of angst as they do not feel prepared for the requirements of the real world.

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 59

CHAPTER 6

They blame this on the outdated school system and educational structures in the country. This study seeks to find out more about the needs and expectations of this cohort by looking at the following two research questions:

1. What do GenZ learners in Germany think about the inclusion of technology and social media in the L2 classroom?

2. How do GenZ in Germany expect the role of their teachers to be to facilitate their learning?

Local Context & Participants

Data were collected in three federal states in Germany, from one Realschule (non-academic secondary branch), one Gymnasium (academic secondary branch) and one Berufsfachschule (vocational college). Originally, 100 participants had signed up for the study, however, due to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, only 20 learners participated eventually. From this total number of participants, 13 attended a vocational college and seven attended secondary schools, with 6 participants volunteering to participate in the follow-up interviews.

Methods

A mixed-methods QUAN → qual approach was chosen to allow for data triangulation (Dörnyei, 2007). The selected data for this paper was harvested from a quantitative questionnaire containing 14 Likert-Scale items. Once the questionnaire was evaluated, follow-up semi-structured interviews were conducted with questions based on the questionnaire findings. Data collection was conducted between April and July 2020.

Results and Discussion

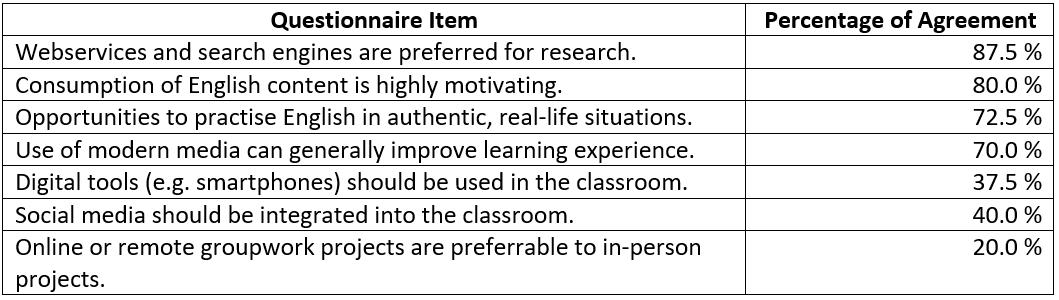

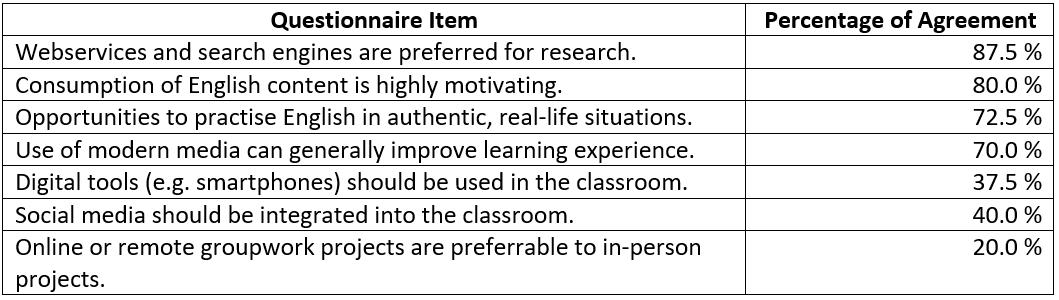

The first research question attempts to identify the preferences towards the inclusion of technology and social media in the EFL classroom. The questionnaire results can be seen in Figure 1 below. It

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 60

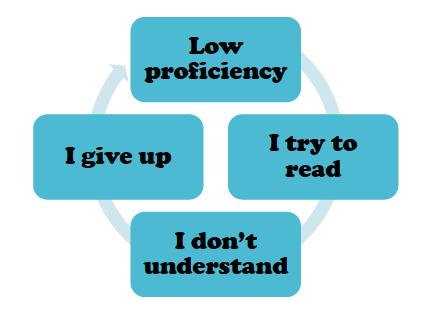

must be noticed that the majority of participants find the consumption of authentic English content (e.g. YouTube clips) and the application of the language in these contexts highly motivating (80.0% and 72.5%, respectively). At the same time, learners appear to be averse to the idea of incorporating digital devices, such as their smartphones, and social media, such as their private Instagram or Facebook accounts, into the active EFL lesson.

This is explained by Interviewee 6, who stated that:

“I would never use social media in class. For me it’s a rather private thing I use in my free time […] and it needs to be segregated from school”

GenZ may be aware of the benefits of connecting leisurely with others online, however, prefer not to do so in class for privacy concerns. Furthermore, GenZ do not seem to use many paper-based resources. Instead, they resort to online search engines for research (87.5%). This indicates that a one-size-fits-all approach using contrived audio-visual teaching materials may be detrimental to the learners’ experience. Instead, a more individualised approach to materials, including online resources of interest, access to online search engines and encyclopedias and the opportunity to exchange

ELT RESEARCH IN ACTION 61

Figure 1. Questionnaire data: Technology and Social Media in the L2 classroom.

language via social media in unmonitored contexts may be beneficial for GenZ’s language learning experience.

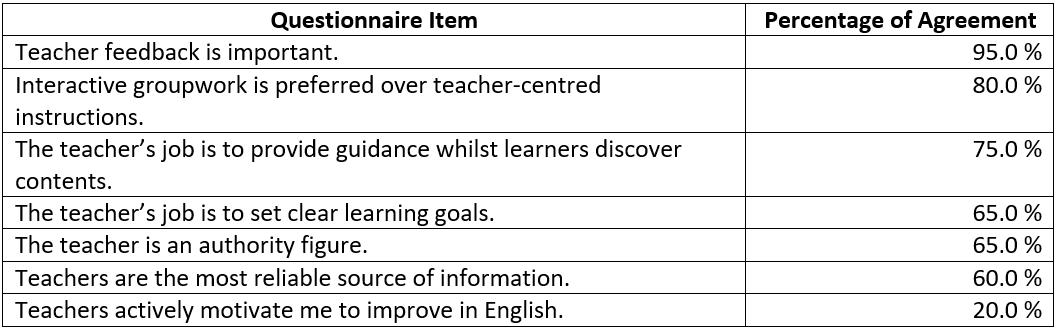

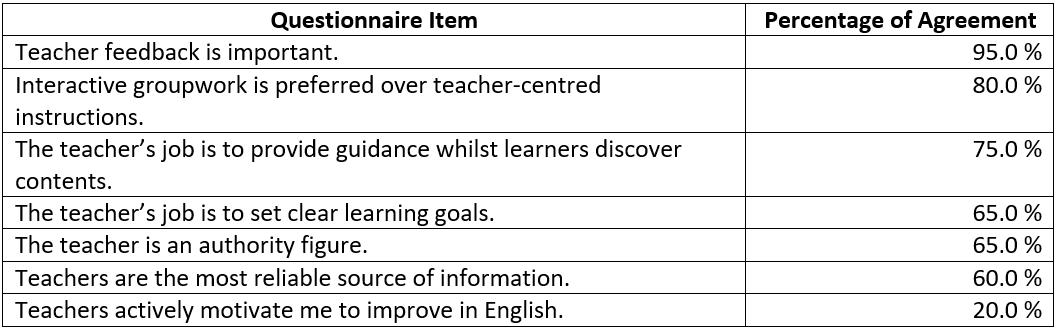

The second research questions attempts to ascertain how learners see their teachers. The questionnaire results can be seen in Figure 2 below. Interestingly, the learners seem to rely on their teachers for feedback, whilst the teacher is not perceived as a source of motivation per se (95.0% and 20.0%, respectively). In addition, the teacher is still seen as an authority figure (65.0%), however, this transpired more in the role of setting goals (65.0%) and being a source of information (60.0%).

Furthermore, it can be seen that teacher-centred lessons are less favoured by GenZ learners, who in turn prefer interactive groupwork (80.0%). This may be corroborated by the result that learners require teacher guidance, whilst exploring contents (75.0%). These suggestions have been confirmed by the interviews, with all six participants stating that groupwork enables them to explore content and decreases teacher-talk, whilst increasing opportunities to socialise. This underlines the need for self-agency and highlights the social aspect of language learning and use. Interviewee 1 corroborates this by stating:

SECTION 2 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 62

Figure 2. Questionnaire data: Teacher Roles.

“I think this whole ‘I stand up front and just read my stuff and don’t really let the students participate…’ I think it should be turned down […] I think the students should engage more […]”

Hence, it can be argued that GenZ require a shift in focus, away from the teacher and towards the students. They require freedom to engage with materials and collaborate on their exploratory quest through the content. At the same time, they appreciate the teacher’s guidance and feedback. This would transform the role of the teacher from emitter to the transmitter of information.

Conclusion

This study aimed at investigating the stance of GenZ towards technology and social media in the classroom and at further defining the role of the teacher in a GenZ classroom. GenZ learners do utilise social media and technology to use English, however surprisingly, they do not wish to include these explicitly into formal instructions in the EFL classroom. This is mainly due to privacy concerns and because social media is considered a free-time activity. Furthermore, it can be suggested that the teacher is seen as a safety net or a passive guide who should give learners the freedom to collaboratively explore contents on their own.

References

British Council (2019). ‘Next generation. Germany’. British Council.