13 minute read

Chapter One: New Designs for Everyday

Stockholm, exemplifing the same spatial strategies used by Aalto to afford the community a worthy and accessible space connected to nature.

Similarly, Stockholm based studio Tham & Videgård were commissioned to design a new architecture and technology school on the existing KTH campus. They were tasked with configuring the academic needs of the school within the circulation role of the site as a campus thoroughfare. Employing central courtyards, curved surfaces and plenty of windows, Tham & Videgård designed interiors which facilitated the needs of the community functionally and beautifully. They did so by adopting the same principles of scale and light as Aalto and Asplund, imbuing the spaces with a sense of intimacy and warmth within the academic context. The spatial analysis of these contemporary interiors combined with the historical context and examples provided demonstrate the direct link between the communitycentric design philosophy of Folkhemmet and the affinity between the individual and the community felt in contemporary Scandinavian interior architecture.

Advertisement

Chapter 1: New Designs for Everyday

This chapter will establish the framework needed to discuss the concept of Folkhemmet, and provide a historical overview of the cultural and political climate in Sweden leading up to, and during, the 1930s. Followed by, introducing the key figures responsible for the introduction of functionalism into Swedish interiors, their involvement in the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, and the lasting effects and success of the Exhibition. Folkhemmet – a home for everyone – was a slogan crafted by the Social Democratic Party to target the welfare issue of housing. It aimed to create a more inclusive society with greater opportunities for practical and safe homes for every Swede. After the Exhibition, functionalism became the architectural tool used to implement Folkhemmet as a way of visually exemplifying the possibilities of modernity (Woollen 2012: 133).

The Interwar period (1918 – 1939) brought with it immense social and cultural change throughout the Nordic countries (Ashby 2017: 133). Sweden, in comparison to surrounding nations, was relatively free from the financial and social strains of warfare due to Swedish Neutrality – Sweden's foreign policy of nonparticipation in armed combat (Agius 2012: 6) – which favourably positioned the country within the rise of modernity (Woollen 2012: 132). Historically neo-classical and national romanticism styles dominated interior architecture throughout Sweden. The Swedish national identity was very closely linked to these traditional styles, and the craftsmanship, skill and history they represented (Ashby 2017). Examples of this can be seen in figure 1.01 portraying the exterior of Waldemarsudde house, Stockholm (1904), and figure 1.02, a residential interior layout where the kitchen and beds shared a room which was very popular at the time.

Figure 1.01: Ferdinand Boberg, exterior Waldemarsudde house, on Djurgården in Stockholm, erected 1904 representing the traditional Swedish façade architecture of the early 20th century

Figure 1.02: Interior view of an early 20th century home in Sweden, depicting the spatial arrangement typical to the time when bedrooms and kitchens shared spaces (Ashby 2007)

The Industrial Revolution during the second half of the 19th century brought with it new needs for industrial cities. People flocked from rural areas to cities at a rate of growth they could not keep up

with. This influx of residents resulted in a national housing crisis, which saw industrial workers and their families living in extraordinarily overpriced and poor living conditions (Marklund & Stadius 2010: 612). Meanwhile, ideas concerning equitable design for the general public had become facilitated by the invention of mass production. The elitist mentality, reserving good design for the bourgeois, began to shift and functionalism became the phrase used in Sweden to designate modern architecture available to everyone, design inherently linked to function, and aesthetic purity enabled by automation (Ashby 2017). The welfare issue of public housing was the main agenda item for the Social Democratic Party, in power at the time. The Party saw Folkhemmet as a political and social system. It described the Swedish people as one national family together under the roof of social equality and welfare solidarity, promising all Swedes improved living conditions (Levine 2018).

"The connection between the ideology and the accommodation was clear; the dwelling was considered to have a central role in an individual's health, morals and work - and thus for society in general. The perception of what was good housing was clear and it was also formulated in rules and regulations, which controlled and had a strong impact on the design of our housings." (Räder 2016: 6)

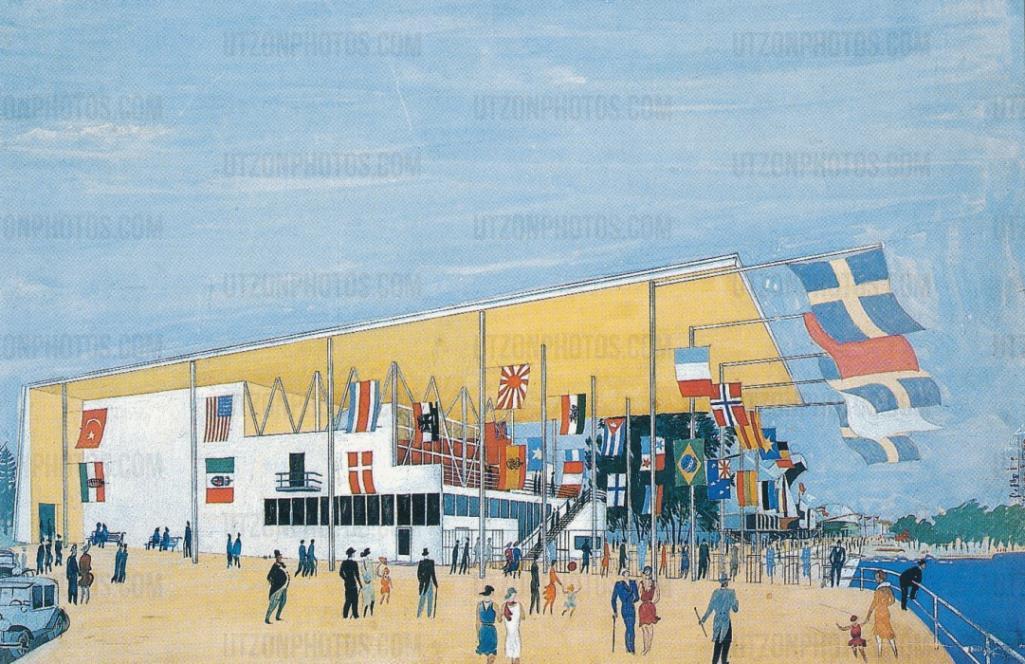

The diplomatic, inclusive attitude throughout interwar Sweden was the driving force behind Gregor Paulsson's desire to ensure the products of architects and artists were available to the entire population, rather than reserved for the esoteric elite, inspiring him to organise the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition (Creagh 2008). Art historian and head of The Svenska Slöjdföreningen – The Swedish Arts and Craft Society - Gregor Paulsson (1889-1977) spearheaded the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 after he visited the Paris World Fair in 1925, leaving displeased with the elitist message of modernism put forth. Paulsson's adopted the modernist trends he had seen overseas and crusaded for advancement in the quality of mass-produced goods, aimed at distancing Sweden from the arts and crafts, neoclassic style of the 1920s (Marklund & Stadius 2010: 612). Paulsson advocated for the democratic welfare ideology of the state, wanting to guide public taste and burgeon "individual culture through collective influence" (Creagh, L 2008: 135). Paulsson partnered Gunnar Asplund (1885-1940) an established Swedish Architect who was well respected and known already for his neoclassical style which littered the streets of Stockholm and assembled a team of distinguished Swedish architects; Uno Åhrén (1897-1977) and Sven Markelius (1889-1972). The purpose of the Exhibition was to express a new Architectural style

on an unparalleled scale, promoting a new direction for Sweden, shifting away from ornamental historical references and towards a united, better society with modern goals and a functionalist rationale (Creagh 2008: 130).

Bearing witness to the success of the Swedish division at the Paris 1925 exhibition and other exhibitions throughout Europe, Paulsson was aware of the power exhibitions had to shape public taste and promote specific ways of thinking. With Swedish politicians keen to allege positions of progression and economic development and architects across Europe designing solutions to address the issues of this new era, the timing was perfect for Paulsson to act (Blundell Jones 2002: 129). Paulsson and Asplund worked to promote a new way of life to the general public by appealing to the minutia of the everyday. Designing and showcasing functionalist housing and commonplace objects such as lamps, plates and letterboxes they were promoting their political message of a strengthened, advanced state on terms accessible by all (Woollen 2012). Social Science authors Kaplan and Ross advocate for the political nature of everyday life "Everyday life harbours the texture of social change; to perceive it at all is to recognise the necessity of its conscious transformation" (1987: 4).

The Exhibition meant for the first-time functionalism could be presented to the public in one dedicated uniform space. Essential to the success of the Exhibition was getting the public on board with a new modern way of living, advancing beyond the rural, ornamental traditions of the past. Paulsson and Asplund did so by arguing that functionalism was in-fact inherently Swedish. Acknowledging the leaps in wealth and prosperity Sweden had achieved in the past 60 years, and linking the aesthetic minimalism presented with their rural culture and closeness to nature, taking on a new form yet still representing their values in quality craftsmanship and rational function (Woollen 2012: 617). Although rural vernacular had little to do with modern urban life, it was relevant in that it reflected the life of ordinary people, an essential theme of Socialist doctrine. It also revealed an honest relationship between function, climate and economy. By giving these rhetorical arguments visual form, the exhibition organisers attempted to resolve the awkward coexistence between traditional culture and the machine and offer a new understanding of the possibilities of everyday life. (Woollen 2012: 132).

Figure 1.03: Gunnar Asplund, grand entrance to the Stockholm Exhibition, 1930, striking clean modernist lines evoke excitement and feelings of anticipation as visitors are introduced to a new way of living

The grand vibrant entry to the Exhibition seen in figure 1.03, showcases sweeping white walls, use of concrete and plywood, paired with exposed structural steel and walls of glass were a significant leap from the architectural vernacular of previous exhibitions. The neon lights and bold graphic signage illuminated the walls of glass and geometric forms, making a grand modernist statement (Ashby 2017). Totally united in its functionalist statement, with no structure allowed to deviate from the central ideology Asplund's modernist pavilions "exploited transparency and asymmetry to the full, while still creating a place of great variety, humanity, and charm" (Marklund & Stadius 2010: 616).

It is important to note that the Exhibition was met with a fair amount of opposition from other board members of The Svenska Slöjdföreningen displaying widespread suspicion of machine automation and concern for the future of handmade craft and their Lutheran values of thrift (Woollen 2012: 620). It is vital to consider them when discussing the cultural climate. However, this dissertation will not address them further.

This dissertation will take a closer look at the Paradise Restaurant designed by Asplund, followed by the housing project designed by Sven Markelius to represent the public and private sectors of the Exhibition. The Paradise Restaurant featured an awe-inspiring glazed semicircular drum of glass, pictured in figure 1.04. The scale and curvature of the glass was a radical modernist take on a Classical façade. The restaurant's central location within the Exhibition and proximity to the water created a social focal point in harmony with the geometric principles expressed throughout the Exhibition (Ashby 2017: 137).

Figure 1.04: Gunnar Asplund’s Paradise Restaurant at the Stockholm Exhibition, 1930, the restaurant is a perfect example of the geometric principles and modernist aesthetics represented through the entire exhibition

Figure 1.05 depicts an east to west sectional perspective highlighting the stacked levels and massive triple height ceilings framing the wall of glass. The circulation from the first floor up to the third is guided by a stairwell on an asymmetrical, angled axis proceeding on to supplementary stairwells with seamlessly positioned points of arrival to capitalise on the view of the festival square. This spatial sequence with running staircases displays Asplund's departure from the straight axial promenades of his Neo-classical works (Blundell Jones 2002: 134). The dramatic, stadium-like viewing experience in the restaurant ensued a thrilling spectacle for the visitors. To produce this, Asplund liberated the front

portion from any visual barriers capitalising on the triple-height ceiling and framed the view of the water and exhibitions space below with enormous windows (Blundell Jones 2002). Towards the rear, the mezzanines and stairwells were significantly reduced in ceiling height, juxtaposed against the grandeur of the restaurant. Highlighting the magnificence and reiterating the principle of balance employed throughout the entire showcase (Blundell Jones 2002: 134). The lightness, functionality and grandeur of The Paradise restaurant fostered a sense of hope for the future inextricably linked to the unity and innovation presented by Asplund and Paulsson (Tyrrell 2018: 55).

Figure 1.05: East to west sectional perspective of Asplund’s Paradise Restaurant highlighting the stacked levels and circulation staircase at the rear of the building emphasising the vast openness of the restaurant gallery

The housing exhibits made up the second portion of the Exhibition, displaying an assortment of model homes in both a freestanding and apartment-style, concerned with maximising space and pleasure within small homes. Deliberately placed after the public sectors of the Exhibition, the homes were intended to be experienced after the visitor had enjoyed and been charmed by architectural wonders of the festival (Ashby 2017: 138). Promoting community was a central value within the Exhibition, Paulsson and Asplund envisaged a society where public spaces were prioritised and successfully shared by all members of the community to compensate for the reduced living spaces. This ideal was to be implemented on the macro down to the micro – within individual homes, social housing projects and entire neighbourhoods. This idea was reinforced as visitors experienced the marvels of the grand restaurants and parks before viewing the space-saving living solutions (Marklund & Stadius 2010).

The main issues residents faced with the current housing situation was the need for different functions to be accommodated within the home, desire for space and light and the need to adapt to different income levels. High rent and low income meant architects such as Sven Markelius were tasked with cultivating optimal living conditions in the smallest space possible (Ashby 2017: 138). Figure 1.06 depicts Markelius' solution to the challenges, through an example of a typical apartment, the living room of apartment 7 in hall 36, proposing a new domestic environment to accommodate a workingclass family of four to six people on an annual income of 4,500-7,000 SEK ($680 – AUD 1000).

Figure 1.06: Sven Markelius, Living room of Apartment 7, Hall 36, a proposed new living environment prioritising light and openness

Light and openness are prioritised, employing the same principals as Asplund's Paradise Restaurant. A glass wall illuminates the main living area and the mezzanine floor which housed two bedrooms and a bathroom offsets the space. The low ceilings were reserved for the rear of the apartment in the study, kitchenette, and dining area to save space, this balance afforded contrast to the usual dark, cramped

apartments (Ashby 2017: 138). It is important to note that this allocation of space reflects the maledominated hierarchy of space coming at the expense of the women on the household. Female domestic duties were relegated to the cramped rear rooms without natural light. This patriarchal ideology was disseminated throughout Europe throughout this modernist regime, however, was swiftly corrected in Sweden throughout the proceeding decades as the patriarchal power balanced out (Ashby 2017). Alongside a new spatial planning rationale, a new home aesthetic was presented, the previous brightly painted wooden furniture had been replaced with strikingly modern use of tubular steel, smooth white walls with no cornices or mouldings. The furniture was all designed to be light and movable, to accommodate flexibility of space and easy cleaning within the limited space (Ashby 2017: 140). Adjustability and moveability were central to the new way of living and catered to the induvial needs of citizens.

Among the four million visitors to the Exhibition was Finnish architect and friend of Asplund, Alvar Aalto who would later go on to be mentored by Asplund and expand the ideas and style of functionalism throughout Scandinavia and back to his home in Finland. After visiting the Exhibition, Aalto wrote:

One can understand the Exhibition has even aroused fierce criticism, being a surgical incision into the deep-rooted tendency to associate the concept of art with a genteel classy lifestyle and its exclusive artefacts. What this Exhibition speaks for is a cheerful, uninhibited daily existence. It makes coherent propaganda for a healthy, unassuming way of living, based on economic realities (Woollen 2012: 157).

The success of the Exhibition in showcasing a new civilisation lay in the uniting Sweden's past, present and future launching modernity into the lives of everyday Swedes and providing solutions to their everyday concerns. The aesthetic style of modernism comprised of stark white, walls of glass and openplan layouts was utterly foreign to the people of Sweden, however, the central values of function, truthfulness and community provided common ground, allowing the Swedish to accept the new style (Woollen 2012).