5 minute read

The Divine Pervades All Creation

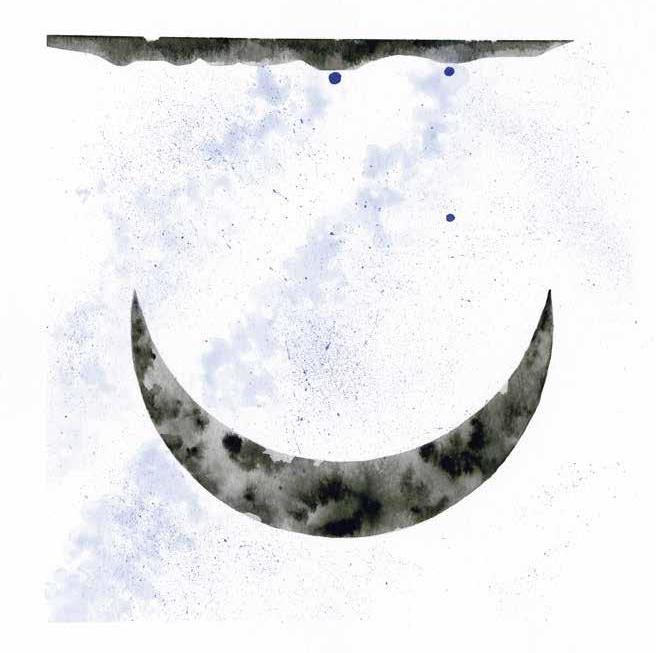

Painting by Dakota Goodhouse, “Haŋyétu Háŋska Wí él Mak ȟ áska Pahá (The Long Night Moon at White Earth Butte).” 2019

by Dakota Wind Goodhouse

Advertisement

Makȟáska Pahá (White Earth Butte), or White Butte, is the highest natural point of North Dakota located in the least populated county of Slope. The only sounds for miles are the whisper or roar of the wind, the shushing of grass, birdsong, the tread of one’s own footfall, or one’s own breath if you’re hiking to this special summit.

The feature is named for the sandstone and white clay that make it up. It rises from the vast open plain like a step to heaven. Shaped by wind and rain, human beings have attached story and meaning to this place since they first saw its bold white profile calling to them. The first hunters ascended this rise in their search for the ancient bison. Men looking for their divine purpose waited days without water or sustenance for spiritual insight. It’s a beautiful walk to the top that naturally invites self-reflection.

The summit is 3,506 give or take a couple of feet depending on which information you use. On the four-mile, round-trip hike the bright orange lichen practically yells for your immediate attention to the cracked sandstone which lay about the hillside.

The Lakȟóta think of lichen as a kind of decoration. They call it Ziŋtkála Ipátȟapi, which means “Bird Embroidery” or “Bird Quillwork.” It does beautify stone. Sometimes lichen is collected and burned as an incense.

A growing number of people have ascended North Dakota’s highest point. Some of them are highpointers, which are people who usually have a list of highest summits of which they ascend and cross them off. Highpointing might include ascending the highest points of counties, states, countries, or the world. Generally, it is an enjoyable experience.

For the indigenous, going to the hill meant going to the top for a look around the land for game as well as for sign of foe. When scouts went out to look, they went out in twos. One might see what the other missed, they looked out for each other, and protected their people with intelligence of the country.

Going to the hill also meant going to pray. Sometimes this way of prayer was for personal guidance, sometimes to secure divine assistance or “medicine” for the survival of the people, even to secure a victory for the people against an enemy. Sometimes people who were called to the hill to pray were inspired or provoked to create stone circles or stone cairns.

White Butte has a deep ancient myth-history that connects the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, the Seven Council Fires (or “Great Sioux Nation”) to the landscape in long occupation.

In the time long predating living memory, a baby fell from the heavens and landed in the heart of Ȟesápa, the Black Hills. He swiftly matured into a young man and set off on a series of missions to help the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, but those are stories and places outside of what is today North Dakota. They called him Wičháȟpi Hiŋȟpáye, Fallen Star.

Fallen Star had a lifetime of adventure akin to the labors of Hercules or the decade-long journey of Odysseus, every quest he fulfilled was to the benefit of the people. He had family and made friends, a wife too, when one day he heard his father calling for him to return and take his place among the stars.

After becoming a father, Fallen Star bid his people farewell. But there is no “goodbye” in the Lakȟóta language. He would have said, “Tokšá akhé,” meaning, “Until next time.” This story may come to an end, but the narrative within makes it clear that the story only continues. With his kȟóla, which is a male friend or cousin who is as close to one as a brother, Fallen Star ascended a hill in the dark of night. He told his kȟóla that it was his time to return to the sky, his time to go home. Then he lay down upon the summit and died.

They saw the spirit of Fallen Star as a light that ascended into the heavens. Even after returning to the sky, his work did not come to an end. From his place in the sky, he labors to send rays of hope to his people.

Sometime during the longest night of the year, from about a mile or so south of White Butte looking north, the Lakȟóta observed a star which appeared to rise from the butte. The badlands formation of White Butte and the summits in the immediate area about the butte bear some similarity in layout to the constellation Auriga, of which the brightest star in that constellation is Capella, the very same star the Lakȟóta call Fallen Star.

As a constellation, Auriga appears to look like the figure of a man reaching up, or perhaps pointing to, the North Star. That White Butte appears to bear some resemblance to Auriga, some would argue coincidence, just as people look to the sky and perceive patterns and images, the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ look and see connection and reflection. That what happens in the heavens happens in the world about them. As above, so below.

This divine reflection of features that is shared between the stars and geography is called Kapémni, which means “To Twirl About,” in reference to the movement of a spinning warclub or a bullroar, but in this instance refers to the movement of the stars across the night sky.

Unlike astrological interpretation, the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ did not try to divine the future of individuals. Rather, the stars in the sky inform them that things were as they should be; the stars had their place in the heavens, so should men and women have their place in society.

South and west of White Butte is Waz’ožúwakȟaŋ Pahá (Sacred Pine Grove Thicket Hills), or the Medicine Pole Hills. A little of the green is collected and burned later in prayer, or perhaps when they saw the Northern Lights. Within the hills, on private land, is Čhaŋgléška Wakáŋ, a sacred stone Medicine Wheel, which is aligned to the solstices. The timing of each solstice indicates an intensity of prayer, a reminder to the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ to be giving.

White Butte, the highest point in North Dakota, where hikers go to experience our natural concert of vast open sky, rushing wind, shushing plains grasses, poetic bird song, and maybe the warning of rattlesnakes. It’s a beautiful unbroken view once you’re atop. Its intrinsic value to people and nature is immeasurable. When you’re there, breathe deep. Look long and far. The moment will stay with you long after. It was special a thousand years ago. What is amazing is that it is still a place of natural majesty. This is White Earth Butte.

DAKOTA WIND GOODHOUSE is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. His traditional name is Ozúye Núŋpa (Two Wars). He holds a B.A. in Theology and an M.A. in History. Goodhouse maintains the history blog The First Scout.