11 minute read

America's Greater Jihad

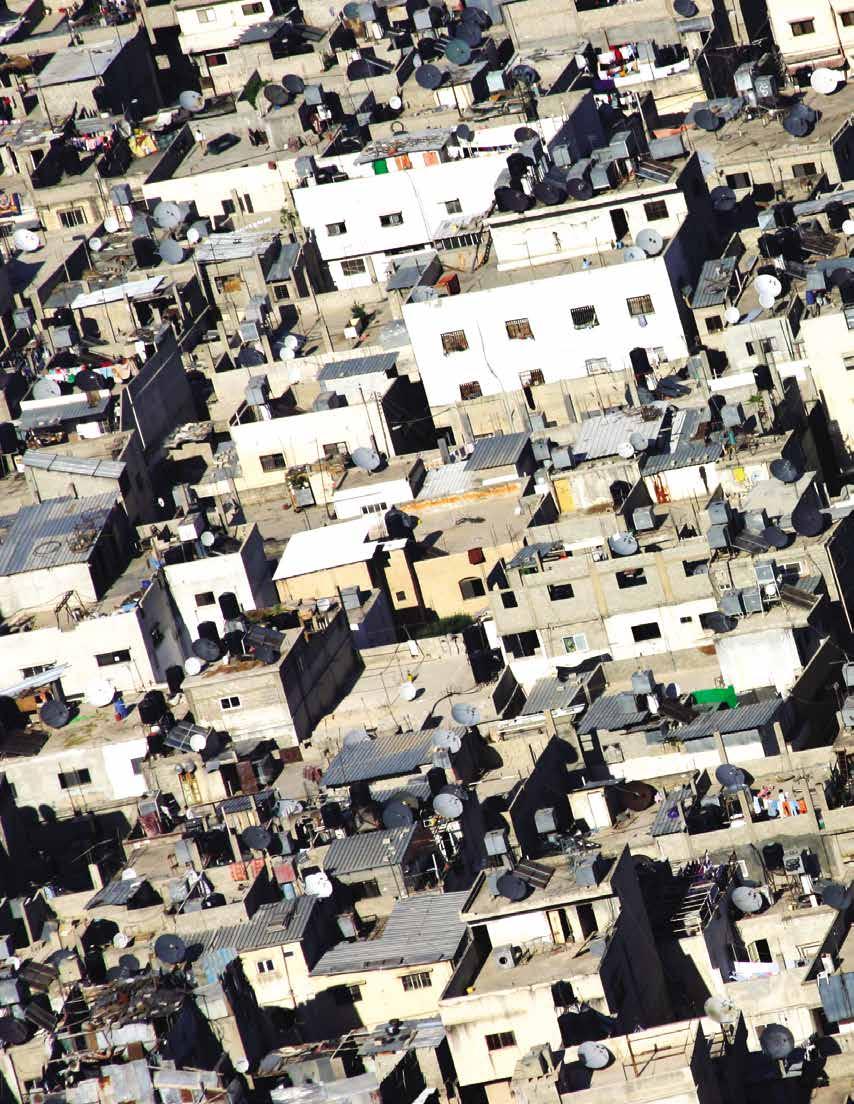

Photo by Josh Rushing.

JOURNALIST AND MARINE CORPS VETERAN OF THE IRAQ WAR

Advertisement

JOSH RUSHING

Josh Rushing has presented twenty-eight episodes of Fault Lines since helping launch the show in 2009. He has covered a wide array of issues, such as NSA surveillance, immigration, and the drug war. On any given day “on location” has meant a death chamber, illegal mine shaft, cocaine lab or battlefield, while “a day in the office” has ranged from hunting seals with Inuit in the Arctic to running from riot cops in Santiago.

A veteran of Al Jazeera English’s earliest days in 2005, Josh has been a leading presence on the air since the channel’s beginning. Josh authored Mission Al Jazeera: Seek the Truth, Build a Bridge, Change the World, published by Palgrave MacMillan in 2007. His writings and photography have been widely published from AlJazeera.com to National Geographic.

Josh became known to audiences around the world as the US Marine featured in the 2004 documentary film Control Room. He resigned from the the corps as a captain after fourteen years.

Josh has four children and a very, very understanding wife.

AMERICA’S GREATER JIHAD

By Josh Rushing

In Arabic the word jihad means struggle, or holy war. Many Islamic scholars distinguish between what they call the greater and lesser jihads: the lesser is the fight to defend the faith; the greater is the struggle to overcome the chasm between the best and worst within oneself.

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, America has been engaged in its own jihads, both the lesser and the greater. With troops deployed around the world presumably defending their homeland (while offending nearly everyone else), one might call it a victory in this lesser jihad that at the time of this writing there have been no new attacks on the United States since the Twin Towers fell. However, reports from the frontlines of America’s greater jihad—the struggle for the nation’s soul, the ideas America is supposed to represent—are much more grim.

For fourteen years as a U.S. Marine I dedicated my life to defending America, but through a surprising series of events I have found myself pulled from the fight against foreign enemies and thrown onto the frontlines of America’s greater jihad, as a correspondent for Al Jazeera English.

I have an office four floors above our studio in a building three blocks from the White House in Washington, D.C. From this vantage point, in the heart of our nation’s capital, I often find myself traversing the battle lines of America’s struggle with the best and worst of itself. Such was the case when I went to shoot a story on America’s dwindling rural population in Small (and getting smaller) Town, USA.

In a country consumed with immigration issues, I wanted to explore a corner obsessed with emigration. Producer Peggy Holter, cameraman Mark Teboe, and I headed to Divide County (population 2,200) in rural northwest North Dakota, just a few miles south of the Canadian border. There I interviewed everyone, from high school students to business owners, about the value of their little piece of the heartland and the risk of it emptying out as young people went away to college and found little reason to return home afterward. I first sensed something might be amiss when a reporter from The Journal, the local paper, showed up to cover me covering them on my first day in the area. She was friendly enough, but after chatting for a bit she admitted to her surprise about how I was dressed. I thought blue jeans and a button-down shirt might appear more casual than what she was accustomed to seeing reporters wear on television.

“No,” she said, “it’s just that when I heard there was a crew here from Al Jazeera I thought you’d be wearing robes and headscarves.”

Although this wouldn’t had been true even if I had been working for Al Jazeera Arabic—the original Al Jazeera—I took the opportunity to tell her about Al Jazeera English, which at the time was preparing its global launch, and the story on “vanishing America” that we were pursuing in her neck of the woods. She seemed fine with my explanation, we parted amicably, and I didn’t give it much further thought until she called me a few days later, sounding more than a little distraught.

She told me that a couple of days after we met, a man who identified himself as an agent from Customs and Border Protection entered her office and asked her to step outside with him. She asked if she could bring her reporter’s notebook, to which he sternly replied, “No need. I’ll be the one asking the questions.” Once out of the office he began to grill her about her encounter with me: Did he look American? Do you think he was a citizen? What kinds of questions did he ask? What were they doing up here near the border? Did they take pictures or videos? The agent informed her there were potential international implications to my visit, on which he was not at liberty to elaborate.

Photo by Josh Rushing.

This impromptu interrogation left her upset, and, since headlines at the time were exposing (and criticizing) the U.S. intelligence services for maintaining a list of private phone numbers they sometimes tapped in search of potential terrorists, she also worried about having been added to that database. Would calling her mother to discuss the interrogation put her on the list as well? She e-mailed her brother in Washington State, who, like his sister, found the story alarming, and hesitated before calling to reassure her. When he hung up the phone, he saw an unmarked car pull up in front of his house. A man leaned out of the passenger side, spray-painted a strange symbol on the sidewalk in front of the house and drove off.

He was dumbfounded by what he saw, and had he not taken a picture of it, even his sister may not have believed him. Overcoming her fear, she wrote a column about her bizarre encounter in The Journal, while her brother recounted his own version of the story on his blog. The fuse was ignited: from there, a watchdog group that wrongfully associates Al Jazeera with Al Qaeda picked up the story and released an urgent media advisory about Al Jazeera probing the United States’s unsecured borders. This story gained national exposure when Fox News ran a note about it on its ticker. A legion of conservative bloggers propelled the incident even further, fanning the flames of their xenophobic followers with visions of Arabs teeming at the United States’s porous border with Canada.

Back in North Dakota, the Customs and Border Protection agent who had visited the reporter was now tracing my footsteps, giving the same big-brother treatment to everyone I interviewed, prompting a series of nervous phone calls to me. They were worried they might have said something that could put their country at risk or, even scarier, something that could put themselves at risk from their own country. The agent effectively burned every bridge I had crossed in North Dakota, ensuring that there wasn’t going to be any follow-up interviews on this story.

All of this might have been more amusing than frustrating, were it not for a bolt of bad news I received the same day I found out about the federal agent following me. In an e-mail from an old friend, I learned that one of my best friends from high school, Matthew Worrell, had just been killed in Iraq when his Little Bird helicopter was shot down in a battle south of Baghdad. Like me, Matt had two sons who looked just like him. Jake was three years old and Luke, which is my son’s name as well, was eighteen months old. Matt’s death hit me hard. At the funeral, his sons wore tiny suits and Luke sucked on a pacifier with a red, white, and blue handle that matched the colors of the flag draped over his father’s coffin.

Photo by Josh Rushing.

Matt’s death reminded me that the struggle, the lesser jihad the United Sates currently faces, comes at a high cost.

What angered me most was that Matt died serving an idea of America—the idea of a nation with an open mind and heart—that resembled the actual state of America less and less, and seemed to be vanishing faster than the people in North Dakota.

The nation was becoming blinded by fear, seeing enemies where there weren’t any, and treating honest inquiry—the kind guaranteed in the Constitution— with suspicion or hostility.

Photo by Josh Rushing.

I called the agent who was on my trail, and this time the questions were for him. Why was he harassing the people I interviewed? If he had questions, why didn’t he contact me? Was this part of his job? To protect America’s unsecured Canadian border from the “threat” of Washington-based reporters? His stumbling answers were meek at best.

The story of my misadventure in North Dakota resurfaced six weeks later when my executive producer, Joanne Levine, mentioned it in an op-ed piece about Al Jazeera for the Washington Post. To accompany her article, the Post editor retrieved an archived photo of a protest that had occurred outside Al Jazeera English’s Washington studio. A group opposed to Al Jazeera coming to America—never mind Al Jazeera Arabic already had a bureau in Washington and had been distributed in the States for years—had spent months on its website calling for a protest, claiming that the launch of Al Jazeera English could lead to suicide bombings on the streets of the United States. The group’s recruitment skills were about as effective as their planning foresight. According to the Washington Post there were all of six protestors outside our office building, denouncing us as a “propaganda shop on American soil.” A spokesman for the United States American Committee—the group responsible for promoting the event—claimed that they had expected at least 200 outraged citizens to participate in what they hoped would be a continuous, round-the-clock demonstration. But by six o’clock, the band of six had gone home. (1)

1 “Al Jazeera Office Protested,” Washington Post, May 1, 2006, p. B3.

I missed the show, though a few of my colleagues went by to see the protest, but like the people who had organized the demonstration, they were disappointed with the turnout. Although a photographer covered the diminutive demonstration, the Post did not print a picture—until they retrieved an archived photo of the April protest to accompany Joanne’s commentary. The photo’s frame was tightly filled with a handful of protestors and their handmade signs, without explaining they were the protest in toto; from the tightly cropped photo you might have though the demonstration was huge.

This is a strange time for America. Everywhere it seems people are seeing things through a prism of their own fears and stereotypes. When the reporter from The Journal in North Dakota heard that a crew from Al Jazeera English was in town, she expected Bedouins on camels. The Border Patrol assumed we were doing reconnaissance for a pending invasion. The reporter’s brother thought secret agents were marking him, but instead, the person in the mysterious car was simply designating a trail for a bike race passing through the neighborhood that weekend. The protestors believed we were bringing an anti-American agenda to the nation’s capital. And my friend died in a war initiated by fears of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and terrorist ties that didn’t exist.

Photo by Josh Rushing.

It doesn’t take an expert to see the signs of a changing time. After being interviewed by Terry Gross on her radio program Fresh Air about my experiences in the war to liberate the Iraqi people, I received an e-mail from a former Israeli military officer who wrote to me: “Six months in the desert doesn’t make you f---ing Lawrence of Arabia.” Granted.

At a time when the historic conflicts of the Middle East continue to impact us in a daily fashion—from the friends we have buried, to the news we watch every night, to the shoes we remove each time we board a plane—I am dumbfounded as to why more Americans aren’t interested in the Arab world. Many Americans seem to know very little about the Middle East, and often broad-brush the whole area. When I am invited to talk, I’m often asked to describe life in Qatar, and regularly people are surprised when I tell them of the luxury hotels, fine seafood restaurants, and beautiful beaches. It seems like people in the States often picture the entire Middle Eastern region as the exploding market place often depicted in Hollywood interpretations of that part of the world.

From my vantage point—working for an Arab-based media company in the heart of the United States, trying to practice skeptical and challenging journalism in a news environment where those values seem increasingly less important—my North Dakota experience has all the elements of a good story: honest, hardworking people; fearful bureaucrats; ignorant extremists; a good soldier who made the ultimate sacrifice; and a few simple twists of fate, such as the stranger marking the brother’s house and the photograph taken out of context. It was as rich and kaleidoscopic as any true picture of our country; and it was business as usual on the frontlines of America’s greater jihad, and my own, personal mission Al Jazeera.

From Mission Al Jazeera: Build a Bridge, Seek the Truth, Change the World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.) Copyright © 2007 by Josh Rushing. Reprinted with the permission of the author, 2014.