11 minute read

West of Kabul, East of New York

Photo by Josh Rushing.

A CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITER FROM AFGHANISTAN TRANSFORMED BY 9/11

Advertisement

TAMIM ANSARY

Tamim Ansary was born in 1948, in Kabul, Afghanistan. His father worked as a professor at Kabul University and his mother—the first American woman to marry an Afghan and live in Afghanistan—taught English at the country’s first girls’ schools. In the mid-fifties, his family moved to the tiny government-built town of Lashkargah, in the country’s southwestern desert. Today, that area is the heart of the Talibinist insurgency. Back then, it was the nerve center for the country’s biggest American-funded development project, a vast complex of dams, canals, and experimental farms, which his father helped to run.

When he left Afghanistan in 1964, the country was still a tranquil backwater. He finished high school and college in the United States, then worked for a collectively-owned newspaper. Later, just as Khomeini was seizing power in Iran, he traveled in North Africa and Turkey, looking for Islam, and found Islamism instead. Unnerved and exhausted, he returned to San Francisco, married the love of his life, and settled into a quiet life of editing and writing children’s books.

Then came September 11, 2001. The day after those airplanes brought down the twin towers, an email he wrote to a few friends went viral on the Internet, and he found himself derailed from his previous career into speaking for Afghanistan and trying to interpret the Islamic world for the West—because at the time there was no one else to do it. In his memoir West of Kabul, East of New York, he depicts how it was to grow up straddling these two vastly disparate cultures— Afghanistan and America. In 2010 he published Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes to critical acclaim, and more recently The Widow’s Husband, a historical novel set in Afghanistan in 1841. In 2012 he released Games Without Rules: The Often Interrupted History of Afghanistan.

WEST OF KABUL, EAST OF NEW YORK

By Tamim Ansary

For many long years, my siblings and I thought we were the only Afghans in America. When I introduced myself to people, they’d say, “Interesting name. Where are you from?” When I said Afghanistan, I could feel myself changing, not unpleasantly, into a curiosity. Few knew where Afghanistan was, and some were amazed to learn it existed at all. Once, in a college gym class, a coach found my free-throw shooting form humorous. “Where have you been all your life,” he guffawed, “Aghanistan?” When I said yes, he was taken aback: he thought Afghanistan was just an expression, like Ultima Thule, meaning “off the map.”

The Soviet invasion put Afghanistan on the map, but it didn’t last. By the summer of 2001, a new acquaintance could say to me, “Afghanistan, huh? I never would have guessed you’re from Africa.”

That all changed on September 11, 2001. Suddenly, everywhere I went, strangers were talking about Kandahar and Kunduz and Mazar-i-Sharif. On September 12, the abrupt notoriety of Afghanistan triggered a volcanic moment in my own small life.

I was driving around San Francisco that day, listening to talk radio. My mind was chattering to itself about errands and deadlines, generating mental static to screen me off from my underlying emotions, the turmoil and dread. On the radio, a woman caller was making a tearful, ineffective case against going to war over the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. The talk-show host derided her. A man called in to say that the enemy was not just Afghanistan but people like that previous caller as well. The talk-show host said thoughtfully, “You’re making a lot of sense, sir.”

The next caller elaborated on what should be done to Afghanistan: “Nuke that place. Those people have to learn. Put a fence around it. Cut them off from medicine! From food! Make those people starve!”

More than thirty-five years had passed since I had seen Afghanistan, but the ghosts were still inside me, and as I listened to that apoplectically enraged talk on the radio, those ghosts stirred to life. I saw my grandmother K’koh, elfin soul of the Ansary family. Oh, she died long ago, but in my mind she died again that day, as I pictured the rainfall of bombs that would be coming. And I saw my father, the man who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, leave when the Soviets put the country in a clamp. He was long gone, too, but if he’d lived, he would be in Kabul now, an eighty-three-year-old man, in rags on the streets, his ribs showing, one of the many who would be starving when the fence was flung up around our land.

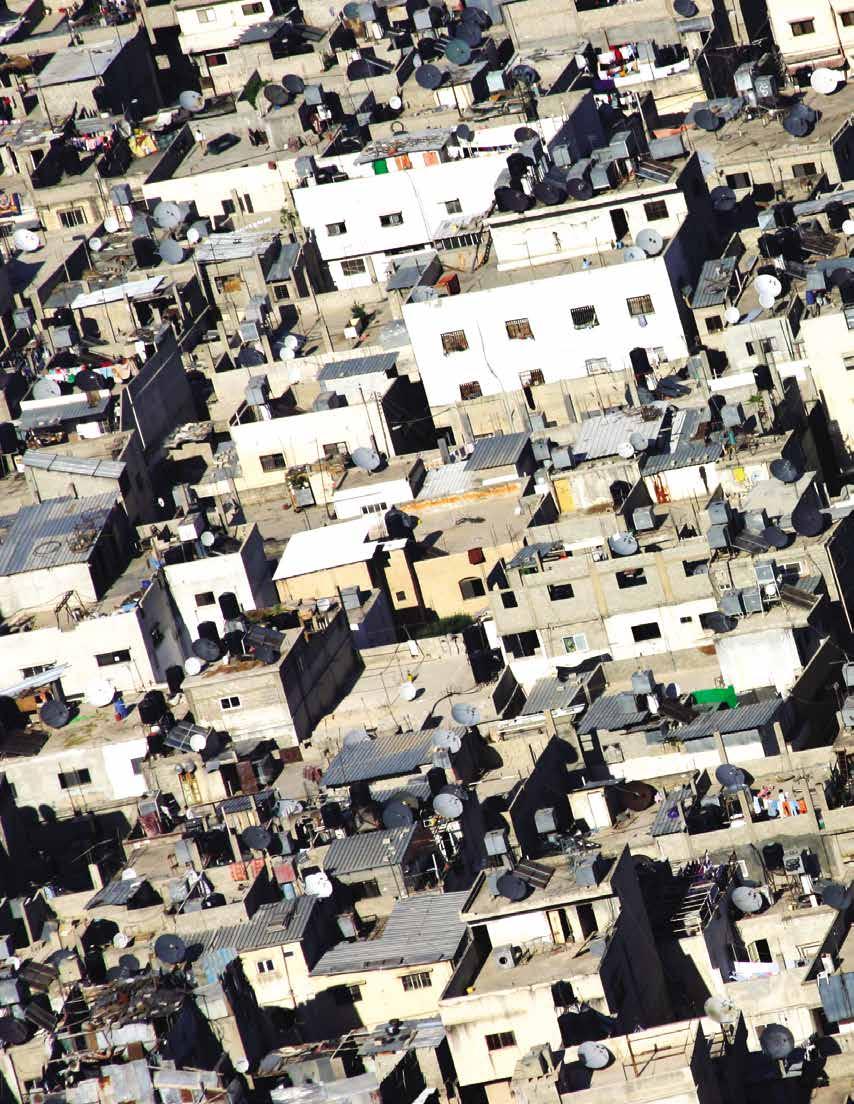

I didn’t begrudge those callers their rage, but I felt a bewilderment deeper than shock. No one seemed to know how pitifully harmless Afghans were, strong contenders for the Poorest People on Earth award, overrun by the world’s most hardened criminals, and now, it seemed, marked out to suffer for the crimes of their torturers.

I wanted to call that talk show, but when I came home, I felt too shy. I’d never spoken to the media on any level. So I went downstairs to my office and wrote an e-mail to a few of my friends. I poured out to them what I would have said to the public if I could have mustered the courage to call that talk show. The moment I clicked on SEND, I felt infinitesimally better.

Later that day, some of the people on my list asked if they could pass my note on to their friends, and I said, “Sure,” thinking, Wow, with luck, I might reach fifty or sixty people.

That night, I logged onto my server and found a hundred e-mails in my in-box, mostly from strangers responding to the message I’d hammered out earlier. It boggled my mind. The power of the Internet! I had reached…hundreds.

The next day, I realized something bigger was rising under me. At noon I got a call from my old friend Nick Allen, whom I hadn’t seen in fifteen years. Somehow, he’d received the e-mail and had felt moved to track me down and say hi.

An hour later, I heard from Erik Nalder, the son of an American engineer, whom I had last seen in Afghanistan thirty-eight years ago. He’d received my e-mail—I couldn’t imagine how—and had felt moved to track me down and say hi.

Then the phone rang again. A caller from Chicago. A hesitant voice. “My name is Charles Sherman…” Did I know this guy? “I got your e-mail…” I couldn’t place him. “You don’t know me,” he said.

“Then how did you get my number?”

“I looked you up on the Internet—anyone can get your number…I just wanted to tell you that…your e-mail made a lot of sense to me.”

I thanked him and hung up, but my heart was pounding. Strangers were reading my e-mail, and anyone could get my phone number. What if the next caller said, “Hi, I’m with the Taliban”? What if Al Qaeda knocked on the door? How long before some hysterical racist sent a brick through my window?

I wanted to cancel my e-mail. “I’ve reached enough people, thank you; that will be all.” But it was too late. I couldn’t withdraw the e-mail. I couldn’t issue corrections, amendments, or follow-ups. My e-mail spread like a virus throughout the United States and across the world. My e-mail accounts overflowed with responses, and the servers had to start deleting messages I had not read. Radio stations started calling—then newspapers—then TV. By the fourth day, I found myself putting World News Tonight on hold to take a call from Oprah’s people—inconceivable! I have no idea how many people received the e-mail ultimately. A radio station in South Africa claimed it reached 250,000 people in that country alone. Worldwide, I have to guess, it reached millions—within a week.

What had I written? I wondered. Why the response? I barely had time to ponder these bewildering questions. The media seized on me as a pundit. The questions came at me like hornets pouring out of a nest, and all I could do was swing at them. From those first few insane weeks, I only remember Charlie Rose’s skeptical face looming toward me with the questions,

“But Tamim…can you really compare the Taliban to Nazis?”

I tried to tell him about that guy I’d met in Turkey, the one in the pin-striped suit who had wanted to convert me to his brand of Islam, and the horror that had filled me as I read his literature afterward, but my long-winded digression wasn’t appropriate for that or any TV show. I stumbled out of the studio, my mind reeling. What did I mean? The words I had used in that e-mail were so brutal. The Taliban, I had written, are a

CULT

of IGNORANT PSYCHOTICS.

When you think BIN LADEN, think

HITLER.

I never would have used such language if I’d thought millions of people were listening. I’m sure I would have measured my language more carefully. But in that case, probably no one would have listened. And had I misspoken? Would I now renounce my words? I decided the answer was no.

Two weeks later, my cousin’s wife, Shafiqa, called to tell me there was going to be a memorial service for Ahmen Shah Massoud that night, complete with speeches, videotapes, posters, and more speeches. I should come.

Massoud was the last credible anti-Taliban leader in Afghanistan, the man who put together the Northern Alliance, a towering figure, assassinated by the Arab suicide bombers two days before the attacks on the World Trade Center. I admired Massoud, and his assassination disheartened me, but I was just too spent to go to his memorials service. “I need to rest,” I pleaded.

Shafiqa was silent for a moment. Then she said, “Listen, Tamim, we are all proud of what you have done. You have written a letter. That’s good. But Massoud slept with only a stone for a pillow for twenty-three years. He scarcely knew the names of his children, because he would not set down the burden of liberating our country. I think he was tired at times, too. I think you should be at his memorial service.”

I hung my head in shame and said I would be there.

The following week, a representative of the Northern Alliance phoned me. “You have the ear of the American media. You know how to say things. We know what things must be said. Let us work together. From now on, you must be the spokesman.”

“The spokesman? For what? For whom?”

“For our cause. For our country.”

I could feel my ears shutting down and my eyes looking for the back door. Was Afghanistan really my country?

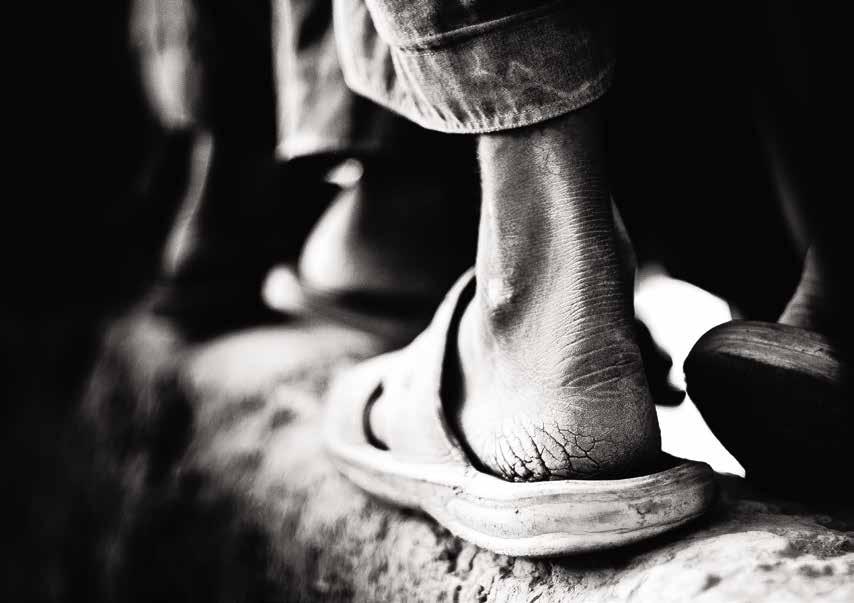

Dear reader, let me pause to introduce myself properly. Yes, I was born and raised in Afghanistan, and I know Islam intimately, from the inside, in my very soul. Yes, I learned to say my prayers from my Afghan grandmother; yes, I know the flavor of sundown on the first day of Ramadan, when you’re on the porch with the people you love, waiting for the cannon that will mark the moment when a white thread can no longer be distinguished from a black one and you can put the day’s first sweet date in your mouth.

But my mother was American, and not just any American, but a secular one to the max, and a feminist back when there hardly was such a thing—the daughter of an immigrant labor agitator in Chicago who would have been a Communist if only he could have accepted orders from anyone but his own conscience. And I moved to America at age sixteen, and graduated from Reed College, and grew my hair down to my waist, and missed Woodstock by minutes, and revered Bob Dylan back when his voice still worked. I made a career in educational publishing, and if you have children, they have probably used some product I have edited or written. I am an American.

How could I be an adequate spokesman for Afghanistan or for Muslims?

“Look, I have nothing to tell people but my own small story,” I told the fellow from the Northern Alliance. “Maybe I can help Americans see that Afghans are just human beings like anyone else. That’s about all I can do.”

“That is important, too,” he said, his voice softened by anxiety and despair.

In the weeks that followed, however, the media kept punching through to me, and I kept answering their questions. It turned out that I did have plenty to say about Afghanistan, Islam, and fundamentalism, because I have been pondering these issues all my life—the dissonance between the world I am living in now and the world I left behind, a world that is lost to me. And as I kept talking, it struck me that I was not the only one who had lost a world. There was a lot of loss going around. Perhaps it wasn’t really nostalgia for the seventh century that was fueling all this militancy. Perhaps it was nostalgia for a world that existed much more recently, traces of which still linger in the social memory of the Islamic world. Lots of people have parents, or grandparents, or at least great-grandparents who grew up in that world. Some people even know that world personally, because they were born in it. I am one of those people.

From West of Kabul, East of New York: An Afghan American Story (Picador, 2002). Copyright © 2002 by Tamim Ansary. Reprinted with the permission of the author, 2014.