10 minute read

The History of Chautauqua

Photo: 1854 Ruston Chautauqua, Louisiana, unknown photographer, 1854. Louisiana Tech University’s Archives.

The name is shrouded in mystery with at least three different translations from the native tribes who used to live upon its shores. One possible meaning is “Bag-Tied-In-The-Middle,” which supposedly references the shape of the lake. A second possible meaning is “Place-Where-FishAre-Taken,” and yet a third translation has it as “Place-Of Easy-Death.”

Advertisement

In 1872, Methodist minister John Vincent had it in mind to offer instruction to Sunday school teachers outside along the scenic lake. In a few short years, the instruction style became so popular that in 1874, Vincent and an associate of his established the Chautauqua Institution. As a religious movement, Chautauqua spread across the country as a religious revival that was frequently hosted in large tents.

Key components of Chautauqua were Christian instruction, preaching, worship, and band music. Gradually, lectures about other subjects appeared in the tent, such as politics, comedy or performance arts, philosophy, culture, and history. The popularity of the movement was undeniable. President Theodore Roosevelt even said it was “the most American thing in America.” But in 1940, the movement stalled. Americans were concerned about the war in Europe and worried about being drawn into the conflict, and Americans had just started to recover from the greatest economic disaster in U.S. history. Though the movement ended, the Chautauqua Institution in New York is still operating.

THE CONTEMPORARY CHAUTAUQUA MOVEMENT

In the 1970s, Everett Albers, NDHC executive director, boldly reimagined and relaunched the modern Chautauqua movement as a series of scholars offering first-person interpretations of historical figures; that is, scholars dressed to look and sound like their subjects, scholars who so meticulously research their subject that he or she could answer contemporary questions based on what his or her subject believed, wrote, and practiced. Dickinson State University, where Albers taught, offers this summary of Albers’ work in the humanities:

"Everett C. Albers, born in the heart of North Dakota in Oliver County and a 1966 graduate of DSU, served the North Dakota Humanities Council as its first executive director from its beginning in 1973 until his too-early death in April of 2004. While a humanities professor from 1969-73, he created an integrated core humanities program. Among his other achievements, Albers created the contemporary humanities tent Chautauqua movement, founded the Great Plains Chautauqua Society, and authored several books and publications about North Dakota. Albers was a pioneer in arranging dialogs between academic humanities scholars and the general public, and was deeply committed to the idea that the humanities belong to all the people of North Dakota and the nation."

The North Dakota Chautauqua was renamed the Everett Albers Chautauqua after Albers’ passing, in memory of his work in the humanities.

Everett Albers, North Dakota Humanities Council, circa 2001.

CHAUTAUQUA COMES TO BISMARCK

Why is the Everett Albers Chautauqua coming to Bismarck? There are many reasons. Located near the confluence of the Missouri and Heart Rivers, the location has been continuously culturally occupied for a thousand years. The location has been historically important, from the Mandan Indians’ Looking Village which was abandoned in 1781 after a smallpox epidemic; the Canadian Red Leaf Fort which was established after Lewis and Clark passed by and was destroyed by the Dakota people in 1818; to General Sibley’s punitive campaign of 1863, when he encountered a force of a thousand Dakota and Lakota warriors in conflict at the mouth of Apple Creek; and the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

The City of Bismarck was established in 1872 as Edwinton, shortly after the military established Camp Greeley. The camp and town changed names in 1873, to Bismarck and Hancock, respectively, in an effort to attract German immigrants to Dakota Territory. The City of Bismarck was once a true wild west town. Brothels and bars lined Fourth Street. In a few years, there were more cowboy types dying of fisticuffs and gunfights than in either Tombstone or Deadwood.

The violent image of the lawless old west town is something that Bismarck reckoned with right away. In fact, the community of Bismarck carefully and deliberately dealt with the outlaw image that the reputation of the old west is remembered by few.

View of the city of Bismarck, Dak. Capital of Dakota and county-seat of Burleigh-County 1883, North Dakota, Beck & Pauli, lithographers, 1883.

CHAUTAUQUA: THE CIVIL WAR: CONFLICTS ACROSS THE COUNTRY

The Everett Albers Chautauqua brings together five great historic characters as different in culture and background as can be: Colonel Ely Parker, the Union officer who drafted the surrender papers which General Lee signed at Appomattox; Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross; Frederick Douglass, a former slave; Little Crow, a Santee Sioux chief in the Minnesota Dakota Conflict of 1862; and Dr. William Jayne, first governor of Dakota Territory and President Lincoln’s personal physician, who will serve as moderator for the event.

The American Civil War and the Reconstruction following are remembered as one of the most trying times in U.S. history. The varied backgrounds of our Chautauqua scholars reflect the American Civil War which reached across the continent to the women at home tilling the fields in their husbands’ and sons’ absence; throughout Indian Country as captured Confederate soldiers were sent west to police the frontier as “galvanized Yankees” so that they wouldn’t have to fight against their fellow southerners; to the slaves who waited for the end of the war to gain their freedom; to the brave women who left their homes to comfort the wounded, dying, and broken on the field of war.

The 8th Minn Infantry Mounted in the Battle of Ta Ha Kouty, by Carl Ludwig Boeckmann, Minnesota State Historical Society.

WE ARE ALL AMERICANS

William Jayne was as interested in politics as he was in practicing medicine. Jayne was born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1826. He entered Illinois College when he was eighteen, then graduated in medicine from the University of Missouri in 1849. Whether it was his Protestant upbringing, education, or by personal convictions, Jayne was as much an abolitionist as he was a “Nativist,” meaning, he believed in curbing immigration and naturalization. He joined the American Republican Party, also called the Native American Party, but more commonly known as the Know-Nothing Party. Shortly after Abraham Lincoln was sworn into office as the sixteenth U.S. president, Lincoln appointed Jayne as Dakota Territory’s first governor.

Frederick Douglass was born and raised in the institution of slavery. His childhood was a horror to recall. He wrote, “He lashed at me with the fierceness of a tiger, tore off my clothes, and lashed me till he had worn out his switches, cutting me so savagely as to leave the marks for a long time after.” Douglass was introduced to letters by his master’s wife, then by sympathetic Anglo boys who lent him their books. Douglass is most known for his abolitionist efforts prior to the American Civil War.

Clara Barton was eleven years old when her brother fell off the roof and nearly died from injuries until Barton nursed him back to health. Barton’s pursuits as an educator became stalled when the board of her school, which she started, hired a male teacher; she took to working for the U.S. Patent Office. Barton’s career was short-lived with the patent office which demoted her from clerk to copyist. Things changed for Barton after the First Battle of Bull Run. She collected medical supplies and obtained permission to enter the front lines to care for the wounded. Barton crossed paths with Frederick Douglass and became not just an advocate for women’s rights, but an abolitionist as well. Barton later founded the American Red Cross.

Ely Parker’s story begins in 1828 on the Tonawonda Indian Reservation as Hasanoanda, or Leading Name. His parents baptized him with the Christian name of Ely Samuel Parker and raised him in the tradition of the Seneca Nation, but, at the same time, sent him to a mission school. His heritage was as important to him as much as becoming a U.S. citizen, and in 1851, he was made the sachem of the Seneca and renamed Donehogawa, or Keeper of the Western Door. Parker took the New York bar exam after years of study but was denied because he was Indian. When the Civil War broke, Parker worked as a civil engineer at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He tried to enlist but was turned aside, again, because he was Indian. Parker knew the Union was short on civil engineers, so he called on his friend Ulysses Grant, who commissioned him a captain. Parker later wrote the surrender papers which General Lee signed at the Surrender of Appomattox. When Lee saw Parker he exclaimed, “I am glad to see one real American here,” Parker responded with, “We are all Americans, sir.”

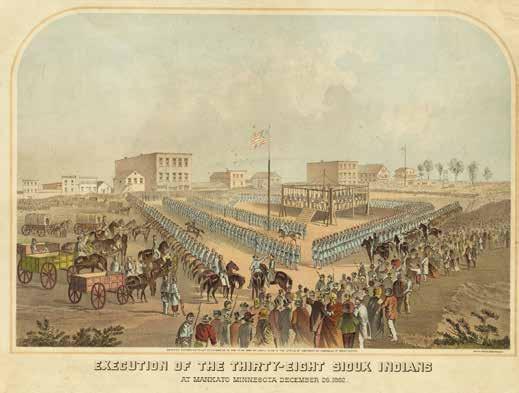

The least understood among these historical figures is Little Crow. Little Crow is perhaps known best for his role in leading the Dakota against settlers in the Dakota Conflict in Minnesota, 1862. His name was actually not Little Crow but Taoyate Duta, which means “His Red Nation.” Little Crow fought with his own brother to lead the Dakota after the death of their father, and won the right to lead. Little Crow signed two major treaties during his chieftainship, both of which had serious repercussions for his people and the settlers who came to the Minnesota River. When the Civil War started, resources such as supplemental food, clothing, and funding halted while they transitioned to the west bank of the Minnesota River. A poor decision by a hunting party to attack a settlement resulted in what some call the Sioux Uprising.

THE CIVIL WAR CAME TO DAKOTA TERRITORY

With most battles in the Civil War fought in the east and south, Americans seldom relate the war to the history of the West. It did, however, spread west to Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and even Dakota Territory.

In 1863, the commands of Generals Sibley and Sully were pulled from active Civil War service and brought west to plan and execute a punitive campaign against the Dakota in retaliation for the uprising the previous year. Their only objectives were to meet and engage Sioux forces, and take prisoners.

Many North Dakotans have heard of two of the campaigns’ major conflicts: Whitestone Hill and Killdeer. The Dakota and Lakota peoples have a difficult time reconciling how the conflicts are known with their ancestral experiences of these sites. For example, Whitestone Hill is promoted as a battlefield, despite North Dakota Century Code only designating it as Whitestone Hill State Historic Site. Native descendants of the Whitestone Hill incident across the Great Plains refer to it as a massacre.

In 1863, General Sully’s command opened fire on the Dakota and Lakota at Whitestone Hill and took just over 200 prisoners, mostly women and children, the rest of the encampment—well over a thousand by Sully’s account—escaped. More Union soldiers died at Whitestone Hill killing each other than by the hand of the natives.

That same year, General Sibley left Fort Pierre a month behind schedule. Sibley headed north along the Missouri River to a rendezvous with Sully at the Heart River. Having missed Sully entirely, but arriving when a Lakota encampment was set up above Apple Creek on a strong bluff, Sibley engaged what he estimated as a force of one thousand warriors over the course of three days. Sibley took no prisoners and could not estimate if his command killed any of the Lakota.

On July 28, 1864, General Sully and his command of more than 4000 soldiers—half of them directly under Sully’s command— the largest U.S. military campaign against an Indian tribe in the country’s history, surrounded a Lakota encampment at Tahċa Kut pi (Where They Hunt Deer; Killdeer). Sully estimated that his command killed up to 150 warriors, though Lakota estimates say 31 lives were lost.

The next day, despite running low on food supplies, Sully ordered a pursuit of the Lakota into the Badlands. A running battle between scattered Lakota war parties and Sully’s command ensued between Sentinel Butte and present-day Medora, which lasted from August 7 to 9, 1864.