13 minute read

Clara Barton: Civil War Nurse

By Karen Vuranch

As Clara Barton lay on her deathbed at the age of 90, her thoughts traveled back to her work on the battlefields of the American Civil War. To be sure, Barton’s selfless service during the war earned her a place in the annals of American history. But, she continued to achieve recognition after the battlefields. Clara Barton was famous even in her lifetime. She was the first woman ambassador for the United States, representing the nation at the Geneva Convention, the first woman prison warden in America, the first woman hired by the federal government in her own name, and, most importantly, the founder of the American Red Cross, as agency she created at the age of 60 and directed for more than 20 years. This agency is her legacy and is still a driving force in the United States today. But, despite these achievements, it was her experiences as a nurse on the Civil War battlefields that she thought of as she lay dying.

Advertisement

While she certainly served in the capacity of a nurse, Barton had no training in the field of nursing. In fact, she was working as a copyist in the U.S. Patent Office prior to the war—one of the few women—and had been a classroom teacher before that. Certainly her life had been one of service and hard work, and she would define herself and her own worth through her service to others, according to her biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor in Clara Barton: Professional Angel. There was an incident in her childhood that exemplifies this need to serve which has been credited by many biographers as a portent of her later life. Clara’s brother David, a dashing daredevil according to Clara in her autobiography, The Story of My Childhood, had clambered up the ridgepole of a newly raised barn in order to work on the rafters. A timber broke under his weight and he fell, causing a head injury. “He had been my ideal from earliest memory,” Clara recalled in her autobiography. “I was distressed beyond measure at his condition. I had been his little protégée, his companion, and in his nervous wretchedness, he clung to me.” For the next few years, David was bedridden, and Clara, a mere eleven years of age, insisted on being his primary caregiver, allowing no one else at his bedside. “I could not be taken away from him except by compulsion and he was unhappy until my return. I learned to take all directions for his medicines from his physician and to administer them like a genuine nurse,” she stated. Finally, after two years of constant care, David did eventually regain his health.

But, with the exception of this incident, Clara had no experience as a nurse. It was the horrific stories of suffering on the battlefield that led her to campaign to be allowed to serve the wounded soldiers. She said, “I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them.” Clara was not alone in her passion to end the suffering of the soldiers. There were many other women nurses working in the hospitals of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, led by Dorothea Dix, as well as countless unaffiliated women who took individual initiative (Pryor, p. 101). What makes Clara Barton distinctive, according to biographer Stephen Oates, is her persistence in working on the actual battlefield. Before Clara served at the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg, all battlefield nurses were male. Clara had to fight the propriety of the time and the commonly held belief that women could not endure the hardship of the battlefield, as well as society’s strict moral code that frowned upon unchaperoned women in company of men.

Indeed, it was the mores of Victorian society that prevented women from nursing. The way for women nurses had been paved just a few short years before in the Crimean War by a group of thirty-eight nurses led by Florence Nightingale. Before Nightingale’s cadre of nurses went to the Crimean front, nurses were considered to be on the low rung of the social ladder, performing menial chores such as emptying slop buckets. In fact, Nightingale herself said of these hospital helpers that they were generally “those who were too old, too weak, too drunken, too dirty, too stolid or too bad to do anything else,” according to Dr. Keith Wilbur in his book Civil War Medicine. Nightingale and her nurses changed the image of nurses from that of charwomen to well-trained and well-bred women. They worked quickly to address the issue of sanitation in the field hospitals and they were able to reduce the death toll from 42 percent to 2 percent (Wilbur, p. 7). As a result of her experiences, Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing in 1859. This book was an important influence on Barton and other nurses of the American Civil War and was one of the first publications to address the importance of cleanliness and sanitation.

Office of Missing Soldiers Tin Sign, Clara Barton National Historic Site, National Park Service.

Sanitation was a crucial issue in the hospitals of the Civil War. By all accounts, these field hospitals were gruesome places. Of the more than 600,000 casualties of the war, it is estimated that more than 400,000, or two-thirds of the soldiers, died of disease and infection in the hospitals (www.civilwarhome.com). What grisly sights would Clara Barton have seen in those hospitals? First, the field hospitals were filthy beyond description. The overworked surgeons and their staff had no time to clean up after a procedure, and had no knowledge of how infection spread. Surgeons would wear the same apron, soaked with blood and other bodily fluids, for each surgery and use the same implements without benefit of cleaning the instruments between operations, leading to extensive infection in the hospital wards.

Furthermore, new technology had been introduced into this war with the invention of the minié ball; a conical, soft-lead rifle bullet that tore through human flesh, shattering and shredding bones (Oates, p. 61). As a result, a new surgical procedure was needed. Surgical resection or excision, which allowed for successful amputation of limbs, began during the war. According to Susan Provost Beller, in her book Medical Practices in the Civil War, resection and excision was not even mentioned in medical texts before 1861. By 1865, Beller states that it rated an entire chapter. The ability to successfully amputate arms and legs did indeed save many lives and led to the development of artificial limbs, a technology that would be helpful to society in general. But, the extensive use of amputation also led to “ghastly heaps of cut off arms and legs,” as Clara records in her diary (Oates, p. 65).

Once the horror of the surgery was past, nurses like Clara Barton would then have to deal with the after-effect, often referred to as “surgical fevers,” resulting from the unsanitary state of Civil War surgery. Indeed, it would be 20 years before doctors understood the importance of sterile conditions. Deadly pyemia (a form of blood poisoning from pus in the blood) or evil-smelling gangrene would often spread through the wound. Pyemia had a 90 percent mortality rate, and to treat gangrene, the surgeon would simply amputate more of the limb. A second amputation had a 52 percent mortality rate, one author estimated.

Besides infection that caused life-threatening dysentery, other deadly infectious diseases were commonplace in the hospitals. Typhoid, cholera, and malaria took the lives of many soldiers and nurses alike. Clara Barton herself suffered from an attack of typhoid fever after the battle of Antietam. Even the medical treatments of the day could be deadly. One of the most controversial treatments was the administration of calomel. Used to treat cholera, calomel was used as a purgative. Unfortunately, calomel is comprised of mercury and caused acute mercury poisoning. The patient’s teeth would loosen, hair would fall out, and the gums and intestines were destroyed, according to Fred Smoot in his web article King Cholera.

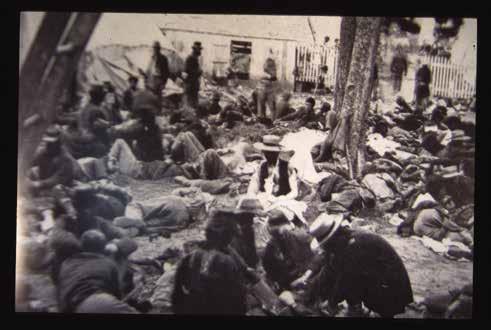

Dead soldiers at Antietam, photo by Alexander Gardner, 1862. Antietam National Battlefield, National Park Service.

Civil War Union Field Hospital, Photo by James F Gibson, 1862. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Infection and disease were not the only enemies in the battlefield hospitals. The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought in the bitter cold of winter. Soldiers were brought from the frozen battleground to houses commandeered as hospitals, such as Lacy House, where Clara served. Soon, the house was overwhelmed with wounded soldiers. Clara wrote in a letter to Soldiers’ Aid Society that the soldiers “covered every foot of the floors and porticos, [they] lay on the stair landings and under all the tables. A man who could find opportunity to lie between the legs of a table thought himself rich, he was not likely to be stepped on” (Oates, p. 116). Once there was no room in the house, and Clara tended men on the porch by heating bricks from a torn-down chimney and placing the hot bricks around the men to keep them warm.

The sheer number of soldiers was daunting. Furthermore, the main supply station was at one end of the house. Elizabeth Pryor, Barton’s biographer, stated that Clara walked the equivalent of 20 miles a night, traveling back and forth between the supply station and the wounded. In fact, it was the experience of Clara and other medical staff in the Civil War that changed hospitals dramatically, creating the pavilion design of today, a central desk with smaller hallways branching off, like spokes of a wheel (Beller, p. 85).

But Fredericksburg would bring another change for Clara. Prior to this, she was the only woman serving on the battlefield, rather than the war hospitals. Originally, her service had been limited to the evacuation sites and she had several volunteers, including some women, accompany her. When she was given permission to go to Antietam, she could only take a male volunteer, Cornelius Welles, with her. However, after the Battle of Fredericksburg, several Dix nurses from the U.S. Sanitary Commission showed up to care for the sick and wounded. Biographer Stephen Oates claims this was an ominous development for Clara, as Miss Dix extended her sphere of influence and sought to exclude all unaffiliated female nurses like Clara from medical service (p. 125).

As a result, Clara left her beloved Army of the Potomac and went to serve the Army of the James, stationed in Hilton Head, South Carolina, further away from the reach of Miss Dix. Clara actually did have authorization from the Army Quartermaster to work with the Army of the James, but still served as a volunteer, without salary. Dix’s nurses, by the way, earned $12 per month, while a male nurse in the army earned $20 per month (Oates, p. 23).

It was while she served in the Sea Islands of South Carolina that Clara tended the wounded after the horrific battle at Battery Wagner. As Stephen Oates puts it, many Union soldiers fought and died bravely there, but the regiment that won the highest accolades was the 54th Massachusetts, a regiment comprised of AfricanAmericans. Clara was as devoted to these soldiers as any, praising their bravery and thinking that justice was served as the black man had been “permitted to strike a lawful, organized blow at the fetters which bound him body and soul” (Oates, p. 174). Clara had been an ardent abolitionist before the war and the exemplary action of the 54th Massachusetts only served to reinforce her belief in the importance of racial justice.

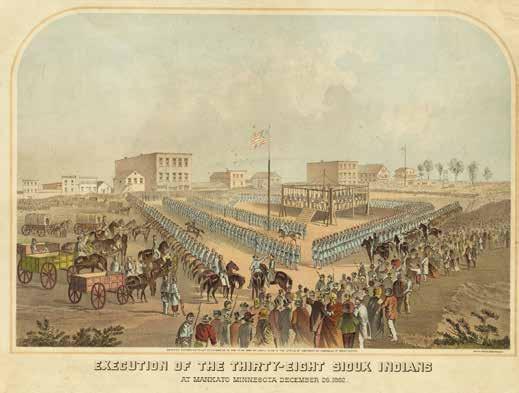

Barton continued to serve as a nurse for the remainder of the war, but another challenge presented itself toward the war’s end. Clara, now famous throughout the nation, received hundreds of letters from women worried about their missing sons or husbands. Clara sympathized with them. Her own brother, Stephen Barton, had been missing behind enemy lines and, when Clara finally found him, he was languishing in a prisoner-of-war camp. Clara was able to procure his release and brought him to Hilton Head to nurse. Sadly, he died of the ravages of the terrible conditions of the prison camps. So, when asked by women to find the whereabouts of missing soldiers, Clara could identify with their loss and grief. She approached President Lincoln with the idea of establishing an Office of Missing Soldiers. Lincoln supported her plan and, following the war, Clara continued to serve her country by leading a campaign to identify the whereabouts of soldiers missing in action. Due to her persistence, the graves of 22,000 soldiers were identified. These efforts included a trip to the notorious southern prison of Andersonville, where thousands of Union soldiers were reinterred in proper graves, and Clara raised the American flag over this new national cemetery.

Clara’s service to humanity did not end with the Civil War and the ensuing work with the Office of Missing Soldiers. Her firsthand experience with the desperate need for supplies and medical help in the face of disaster led her to create the American Red Cross, an agency that continues to this day to provide war and disaster relief.

Although Clara Barton was both catalyst and inspiration for the success of the American Red Cross, it was her days nursing on the battlefields of the Civil War that remained her glory days, and she often recalled those experiences throughout her life. As she lay dying, it was the battlefields of the Civil War that she relived in her mind. She had fallen ill with pneumonia shortly after celebrating her ninetieth birthday and, as the days progressed, she grew worse, drifting in and out of consciousness. On April 10, according to her biographer Pryor, she suddenly awoke and told of a dream she had where she was again on the battlefield, wading through blood and watching the men in agony. She said, “I crept round once more, trying to give them at least a drink of water to cool their parched lips.” Two days later, the beloved heroine of the battlefield passed away, leaving a legacy of selfless commitment to the service of others.

KAREN VURANCH Storyteller, actress, and writer Karen Vuranch weaves together a love of history, a passion for stories and a sense of community. She is known for her traditional storytelling, plays based on oral history, and living history presentations of famous American women. She brings history to life through her unique performance style, which combines storytelling and drama to create an engaging presentation.

She has an M.A. in Humanities from West Virginia Graduate College and teaches Introduction to Theater and Speech and Appalachian Studies for the Concord University Campus in Beckley. Through her interest in the humanities and belief in the importance of communities, Karen has built a reputation gathering oral history interviews and turning those true life experiences into performances. She feels it is important to preserve the personal and family stories of a community. She conducts residencies with elementary through high school students, teaching them to interview their family members and, in turn, tell their family stories. Recently she received a letter from a woman in West Virginia who took part in a group session Karen conducted when she was gathering oral history for a new play. The woman wrote, “Thank you for your workshop. I never thought before that my life was important. Now, I know that I am part of my country’s history.” Karen Vuranch is available for performances, workshops and residencies. She performs regularly for conferences, banquets, schools and arts events.

WORKS CITED

Barton, Clara. The Story of My Childhood. NY: Baker & Taylor Co., 1907.

Beller, Susan Provost. Medical Practices During the Civil War. Betterway Books, 1992.

Hicks, Robert. Widow of the South. Grand Central Publishing, 2005.

Goellnitz, Jenny. http://ehistory.com.osu.edu

Oates, Stephen B., A Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War, NY: The Free Press, 1994.

Pryor, Elizabeth Brown, Clara Barton: Professional Angel, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987.

Smoot, Fred. Sickness and Death in the Old South: King Cholera. http://www. tngenweb.org/darkside/cholera.html

Wilbur, Dr. C. Keith. Civil War Medicine. The Globe Pequot Press: Guilford, CT. 1998.

http://www.civilwarhome.com