10 minute read

Kicking the Loose Stones Home

By Paul VanDevelder

Excerpted from “Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire Through Indian Territory,” by Paul VanDevelder, published in April 2009 by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2009 by Paul VanDevelder. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Advertisement

As they often do, the idea for this book began with a very simple rhetorical question: how did we get from there to here? How, in a blink of time, did we morph from a tiny republic of three million mostly illiterate and ethnocentric Europeans, in 1787, to a nation of 300 million mostly well-educated and genetically diverse Americans who represent every ethnic group and culture on the planet?

It’s a ridiculously loaded question, of course, and I had probably asked it many times before without ever giving the answer any serious thought - for its very ridiculousness. With extraordinary patience, effort, and scholarship, historians and journalists have been writing thousand page books for well over a century in hopes of answering tiny slivers of that question. But on a warm June day in 1996, I must have been in an expansive mood. My mother and father and I happened to find ourselves a mere hundred miles apart, on opposite sides of the Great Smokey Mountains of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina, so from our homes on opposite coasts, we had made a date the previous week to meet in the small mountain village of Cherokee on the North Carolina side of the mountains, where my mother was planning to visit the Eastern Band Cherokee tribal headquarters. Having learned a great deal about sleuthing valuable information from historical records in a Library of Congress course on genealogy, my mom was hoping to track down some elusive answers to questions about her mother's murky family of origin.

Like most American families whose widely flung ancestors arrived on these shores more than a generation or two ago, the thick trunk of our family tree is held upright by a deeply tangled and ever-expanding ball of roots. The family gene pool, as they say, is now as deep as the ocean we crossed to get here. In our case, most of these roots are easily traced backward until, willy-nilly, they disappear into the mists of time in Holland, England, Ireland, and Scotland. But due to reasons my grandmother took with her to her grave, her robust genetic make-up - one that produced high cheekbones, bright eyes, great physical stamina, and thick curly hair - occupied its own special place in our family's treasure chest of speculation and rumor.

None of us ever heard my grandmother claim any particular lineage or country of origin. Any suggestion that she might have Indian blood flowing through her veins was met with a flash of anger and fierce denials. But Julia's life-long denials were not enough to stop her daughter, who, after all, had a stake in finding some answers. What's more, my mother knew enough about the South, about the lowly station of the Indian in the stigmatized social pecking order of the early 20th century, to recognize a culturally reinforced denial system when she saw one. So, with microfilm in hand, the three of us stepped into the small air-conditioned library beside the tribal offices and proceeded to thread the film from the National Archives through the glass plates of the reader, and onto the pick-up spool. Then, having no particular strategy or master plan, we probably did what most people do - we started walking backward toward those distant mists of time where all lines merge and disappear. By searching the tribal rolls we hoped to find some relic or fragment of our family's story, one that filled in the remaining blanks to those familiar questions: Where did we come from, and how did we get from there to here?

As we peered at the screen and watched thousands of names on the tribal rolls scroll backwards through the decades, type written names soon became hand written entries in photographed ledger books. We slowed down, our lips moving in silence, as we read the names approaching the turn of the century. Then, with one slight twist of the knob, the picture froze on the screen. My mother's finger reached out and pointed at a name. I fiddled with the focus and magnified the page. Instinctively and simultaneously, our three heads moved closer to the screen. A moment, a very long moment, passed in speechless silence as we searched each other's eyes with astonished smiles.

"That's your great-grandmother, when she was a little girl, and all her brothers and sisters," said my mother. "My mom‘s mom. Well how about that! We were Indians, too!" There we were, all tangled up together in one enormous and enigmatic ball of roots, indigenous citizen fused with the immigrant. The three of us were astonished and elated and not a little bewildered, as though we were meeting a long lost set of first cousins for the very first time. I was, if nothing else, the genetic embodiment of our nation's story. As I drove away from the little library in Cherokee, this seemed like a story worth telling, a crossing worth the storm.

Strewn throughout this story are the bloody fragments of things Americans have held dear and loathsome for more than two centuries. It has cowboys and Indians and aristocrats and common folk. It has legendary orators and egoistic geniuses, a 'new world order' and lost causes galore. But the protagonist, as stated or unstated in all tales that are truly epic and truly American, is the land itself, that landscape of paradox where boundless optimism and limitless possibility inevitably ran up against a bulwark of human appetites and stubborn desires. On the eve of his inauguration as our nation's first president. George Washington recognized that paradox in full measure. As his biographer Joseph Ellis tells us, Washington realized with mounting dread that “…what was politically essential for a viable American nation was ideologically at odds with what it claimed to stand for." A strong central government would inevitably come to mortal blows with the southern tyrants who were jealous of its authority, and if history could be used to measure the essential ingredients of man's nature, for good and ill, then for Washington a day was already marked in the future when the newly solemnized rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness“ would be vanquished by “venality, corruption, and prostitution of office for selfish ends.“ His Excellency's genius, concludes Ellis, was in his faultless and prescient judgments.

Out of that paradox, out of the deep fissure that divided political ideals and fervid aspirations, grew a resilient but lightening-struck sprig that become a nation, one that was fertilized across time by great themes that continue to shape our story: promise and possibility, betrayal and loss, and the ever hopeful quest for reconciliation. To fully appreciate how all this came about it is important for us to recognize that the dominant paradox in our story was written into America's script three centuries before Columbus stepped ashore on the island of Salvador, in 1492. In 12th Century Europe, a succession of brilliant Catholic Popes – men who wielded iron fists in order to rule and bring order to the geopolitical chaos known as medieval Christendom – also created the laws that enabled them to send crusading armies into the Holy Lands to confiscate land from Muslim ’heathen‘s and infidels.“ As we will see, after those laws evolved through the discovery-era courts of Spain and through the Elizabethan courts in England, they acquired the names by which we know them today: the Doctrine of Discovery and its more familiar offspring, eminent domain. More than half a millennium after the Pope‘s Christian armies sacked Jerusalem, the Medieval papacy‘s building blocks of empire would evolve into the legal fulcrums that the U.S. Congress used to open up western lands to migration and settlement – our story.

In our literature – where we sometimes find the best stories about ourselves – the American epic began taking shape the moment Fennimore Cooper turned Natty Bumpo loose into the primeval forest of his Leather Stocking tales. The path that Natty follows west marks a new frontier in human experience, a boundary that separated a new “American story” from the stuffy parlor dramas of England and France that were played out by gifted proxies on the eastern seaboard. “Eastward I go only by force,“ wrote Thoreau, “while westward I go free.“ By the mid-nineteenth century, the story of going free had been spun through with enough romantic dust to lure a ceaseless procession of settlers toward the setting sun for half a century. Wagon caravans cut ten-inch deep ruts into limestone bedrock in eastern Oregon that are visible today. And on they came, many tens of thousands of them, drawn into the wilderness by desires so fierce and a sky so vast that the silence drove some of our heartiest dreamers to madness. By 1845, trail bosses started referring to the Oregon Trail as “the longest graveyard in the world.“ Yet onward they came, undeterred by the challenges, boldly kicking loose stones toward a home they had never seen, toward a distant day when the dream would either materialize in glory or disintegrate into ashes.

As indispensable to migration as the Conestoga wagon was the single legal tool that made it all possible - the Indian treaty. Indian treaties, hundreds of them, were bargained for by U.S. Congress as the “supreme law of the land“ under Article VI of the U.S. Constitution. In time, as the contest for sovereignty between the states and the federal government ran irrevocably toward Civil War, Indian treaties would be grafted onto federal laws in a manner that subordinated state laws and regulations to compacts with the tribes. Just as George Washington feared in the closing days of his presidency, this fatal quirk of federalism would translate into incomprehensible misery for the American Indian in the 19th century. Nevertheless, as settlers gathered in increasing numbers on the western frontier and clamored for the right to subdue and populate the new Edens of California and the Pacific northwest – the treaty was the government‘s most useful tool for securing a restless society's feverishly desired end. Throughout the half-century long era of westward migration, solemn “supreme law of the land“ compacts with the Indians became the immigrant's stepping-stones to empire. This is the story of those metaphorical stones, including one stone in particular, and the paradoxical forces that laid them end to end, and the journey we made across them to the fulfillment of our nation‘s presumptions to “Manifest Destiny.“

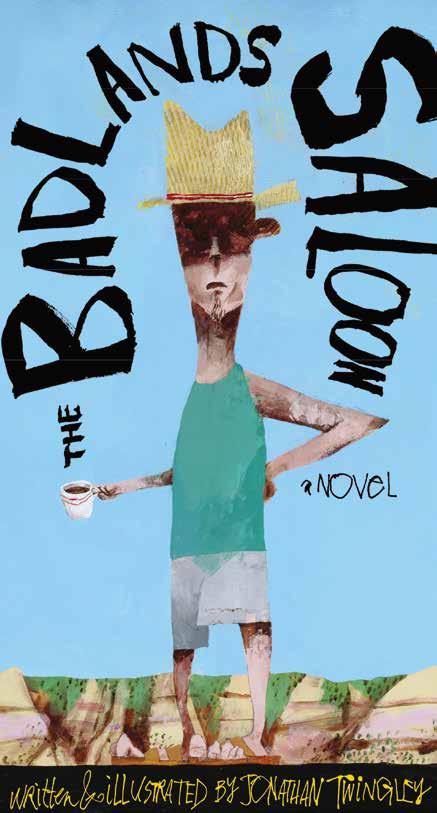

By the end of his life, Cooper‘s Natty Bumpo realizes that the freedoms he imagined, freedoms so beautifully symbolized by the vast panorama of the American West, were cruel illusions. When Natty lies dying on the prairie as an old man, what he hears as life runs out of him is the sound of wagon wheels approaching in the distance. “The one true thing about every American frontier that seems concrete and immutable,” writes Charles Pierce, “is that it does not last. Sooner or later, everything that makes it a frontier collapses into maps and charts and roads and cities, and it becomes a place where we all go and live.” It is in those places, those towns and cities where we finally ran out of wilderness, that we are compelled to reconcile the paradoxes that brought us together in the first place. Like the currents of the Mississippi, or the force of gravity, a young and restless American society could no more escape the violent pull of westward migration than it could avoid the consequences of betrayal and loss that were its end product. But reconciliation, says the western writer William Kittredge, is America's only way out of that legacy, the only sensible path to a future worth living – our Last Chance Saloon.

For the weaver of tales that germinate in such storied soil, no source can substitute for walking the frozen ground in a February wind, for listening to the solitary voices of people whose bones were formed from its dust, or for the sizzle of starlight on a winter night, and the song of a meadowlark on a spring morning. In any search for the true and authentic America, one whose residue of betrayal and loss are redeemed by the endurance and reconciliation of its resilient citizens, there are no proxies for the people whose lives and voices animate these pages.