16 minute read

Can the Diametrically Opposed Landownership Views of Indians and Whites be Reconciled?

By Greg Gagnon

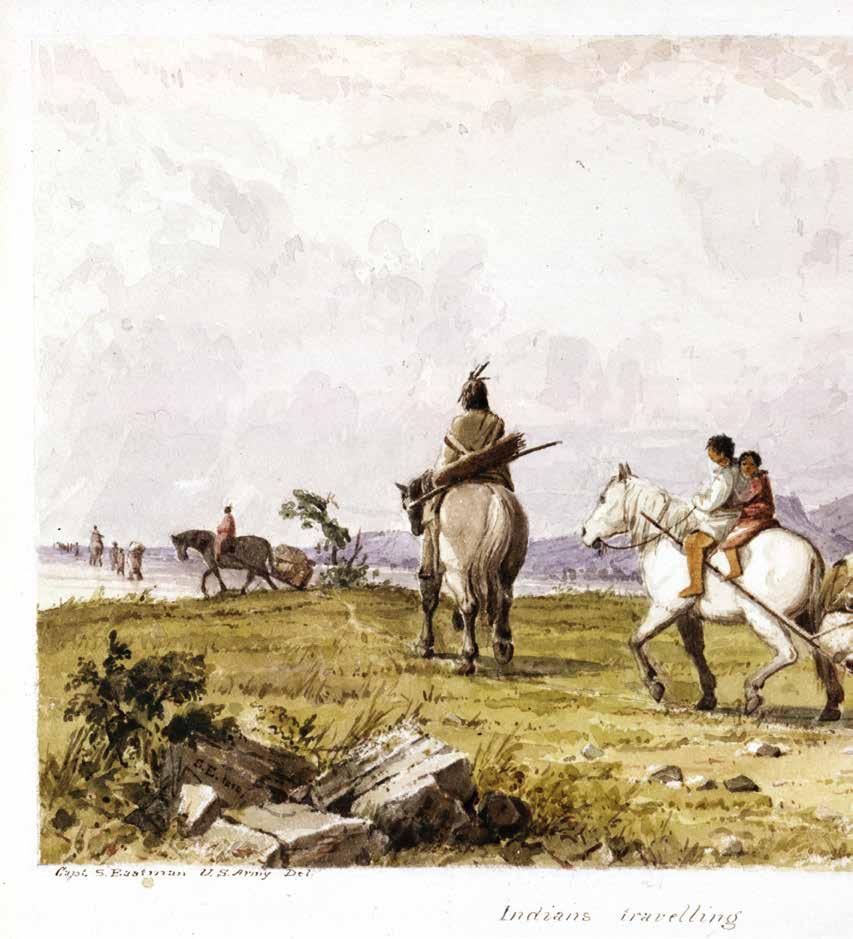

Native Americans of the Great Plains lived in a highly mobile culture. Villages migrated seasonally, following the bison that provided necessities of plains life. Said elder medicine woman Pretty Shield (Absaroke/Crow), I loved to move... Moving made me happy!”

The W. Duncan MacMillan Foundation

Advertisement

Yes……BUT…..the answer is nuanced. It all depends. If one is to understand the answer, it is important to understand the historical context of landownership that requires reconciliation.

In the beginning, American Indian and non-Indian views of landownership were mutually exclusive. They remain so today but aboriginal views have modified drastically under the pressure of historical events and American policies. For purposes of clarity, the term “American” refers to United States society and government policies. Indian indicates Native Americans and tribal governments. Of course, Indians are American citizens and the division is artificial, but it is preferable to describing political and world view differences as if somehow they were based on genetic characteristics. “White and Indian/Native American” are both constructs but are generally used to designate race which is itself a construct. Indian Americans and tribal governments generally do have a different view of land issues from that of the rest of Americans.

Another clarification is needed. Indian tribal/ reservation governments are sovereign polities. They are the third form of sovereign government in the United States; the other two are the federal government and the state governments. Local county and municipal governments are not sovereign; they are created by state governments. Any discussion of views toward the land and landownership needs to begin with this understanding. Tribal sovereignty is embedded in American law and the constitution. It is supported by court decisions and congressional law. Tribal governments combine the world views of tribal ancestors with the major modifications generated by historical events over the past 400 years or so but particularly formed since the United States incorporated independent Indian nations into the American system.

The American view has remained essentially the same since revolution created the country. Based on English law, American law operates on the assumption that the United States holds title to all of the land within its boundaries. This land was acquired, as Chief Justice John Marshall opined in 1823, through the Right of Discovery vested in European Christian nations as their right to govern non-Christian peoples as “discovered” by Europeans. This Doctrine of Discovery is much more elaborate than described here and can be read in all of its legal fiction glory in Johnson v. Mcintosh. The original inhabitants of the Americas did not own land. Indians had the rights to use the land until the United States and only the United States acquired these rights through purchase or just wars. Of course, the Indians did not see it this way. Each Indian tribe insisted that their land was actually theirs.

Americans made private ownership of land by individuals the basic principle of land use. Individuals bought or were given American land from the government and then the land belonged to the individuals who were free to use it exclusively. Private property was, and is, considered the foundation of American society. The Bill of Rights specifically requires due process compensation for land taken through eminent domain. The founding fathers did not want it to be easy for the government to take private land.

When Indian tribes were independent nations, their landownership principles revolved around the concept of collective ownership with land use determined by tradition. Individual Indians did not own the land. The land was considered to have been acquired from the bounty of benevolent spiritual powers or tribal expansion into other tribes’ territories. Although the process of land allocation within tribal territories varied a great deal among the myriad Indian cultures, the principles were consistently the same. Extended families were allowed to use lands according to their needs. Large families got more land than small families but as circumstances changed, so would land assignments. Most Indian groups moved from area to area within their territories. Those tribes that were most mobile like the plains Lakota or Cheyenne had no need for even family assignments so they just used what was needed for hunting and gathering and maybe a bit of farming. Those tribes like the Chippewa which dispersed into family groups during the winter often used the same trapping areas year after year. In a sense, the family “owned” the use of this land. More sedentary agricultural tribes allocated land less frequently.

Groups not from the tribes that owned a particular territory crossed tribal borders within specific protocols. Enemies crossed boundaries between tribes at their own risk. Unknown groups sought permission once they came into contact with the tribe that owned particular land. Allies were welcome to cross boundaries as it was understood that they were mere sojourners. They could hunt and maybe even stay for awhile but they were subject to the tolerance of the owning tribe. Parenthetically, visitors were not allowed to take from the land anything more than sustenance. For instance, any foreigners who tried to trap beaver for the fur trade or kill buffalo for the hide trade were subject to sanctions. No one minded that Lewis and Clark lived a winter and hunted for food. Had they started trapping for market, the situation would have changed. Many mountain men learned this the hard way.

Differences between American and Indian views of landownership should indicate where the conflict emerged when Americans applied their laws and understanding to the acquisition of land from tribes. Indians viewed land as being used by tribal members as needed but not the exclusive possession of anyone; Americans saw exclusive rights for individuals as the key to land use. As Americans took more and more control of Indian tribes, Indians had to learn about private property and the American assumption that the federal government had the right to do as it wished with Indian land. Property rights were learned the hard way by Indians.

America’s constitution provided for the federal government, particularly Congress, to have responsibility for relations with foreign powers and Indians. The constitution did not elaborate on the relationship between Indians and their governments within the boundaries of the United States. Americans arrogated to themselves the right to govern Indian nations because their view was that Indians were an obstacle to civilization that should be removed. Most concluded that Indians had no real landownership because they roamed the land like animals and did not improve the land the way Americans did. In the realm of legal fictions, facts do not count but power does. Early court decisions confirmed American views with some modifications.

Three decisions written by Chief Justice John Marshall established the relationship between Indians and their governments and the United States and its populations. Johnson v. Mcintosh (1823) established the precedent that Indian tribes could not sell land to anyone other than the United States. Indians had only possessory rights which the United States needed to acquire before it sold or gave the land to Americans. Cherokee v. Georgia (1831) declared that tribes were “domestic dependent nations” subject to the jurisdiction of the United States but that America had a duty to protect them. Tribes had legitimate governments based on their inherent sovereignty. Their relationship to the United States was like that of a “Guardian to a ward.” From this legal fiction came the principle of the Trust Responsibility. Which indicates the United States has a responsibility to protect Indian land rights and to provide services and assistance to Indians. Trust land is Indian land that the United States pledges cannot be removed from Indian possessory rights. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) established that states do not have jurisdiction within Indian country, but Congress can make laws that affect Indians and their governments.

Indian-American treaties reflected both Indian and American views of the land. Indians and Americans imposed their mutually exclusive concepts on each other as best they could. Americans insisted on boundaries describing exclusive rights. Indian leaders insisted on retaining the rights to hunt, fish, and traverse lands they were “selling” to the United States. A good illustration of this can be found in the Old Crossing Treaty of 1863.

America bought the Red River Valley from the Red Lake and Pembina bands of Chippewa. Perceptions of what this sale entailed are a bit more complicated that a simple land taking for money. The Old Crossing treaty stated that the Americans and the Chippewa were allies. Allies shared land in the Indian view. The treaty proceedings clearly indicated that Chippewa band leaders were told they would be able to hunt and fish as they always had, even if the United States bought it. Indians did not internalize the American idea of exclusivity and Americans could not understand why Indians thought they could keep using the resources of the lands they had sold. Most treaties and agreements between Indian tribes and America repeated similar misunderstandings.

By 1880 all Indian landownership was restricted to the reservations the United States was willing to permit Indians to keep. Land was still held in common under the aegis of tribal tradition. Indians had managed to retain about 120,000,000 acres. Americans quickly moved to impose their views on Indians. In 1887 the Dawes Severalty Act, also called the Allotment Act, forced Indians to accept the principle of individual landownership.

Reservations were surveyed into townships and sections. Each adult male was told that a specific 160 acres were his. Women and minors received lesser allotments. On nearly every reservation, land remained after the allotments were completed so America declared the land “surplus.” Surplus lands were then made available for purchase by non-Indians. One result is that many non-Indians acquired land within the boundaries of reservations and demanded the right to self-governance of Americans. The process created a checkerboard effect. Indian trust land alternated with nonIndian owned parcels all over the reservation. Today, nonIndians own 28 percent of Turtle Mountain Reservation, 76 percent of Spirit Lake Reservation, 63 percent of Standing Rock Reservation, and more than 50 percent of Fort Berthold Reservation.

The Dawes Act provided for a twenty-five-year period for Indians to get used to private ownership. This was deemed enough time for them to learn to be like Americans. They were to be farmers or even ranchers wresting a living from their 160 acres just like the Americans who lived among them on surplus lands. Once the waiting period was over, Indians were to be given fee patents for their land and become just like other Americans including citizenship and were subject to land taxes. The goals of American policy were to eliminate collective use of land and to destroy tribal cultures.

Congress, urged by assimilationists, shortened the waiting period and ultimately directed Indian agents to simply issue fee patents to those they thought could handle it. Many Indians lost their allotments to delinquent tax courts or simply sold the land they could not use to Americans who had the money to buy. Before allotment was halted by a change in Indian policy in 1934, two-thirds of all Indian land had passed from Indian ownership

After the 1934 cessation of allotment, Indian lands were not alienated as quickly although erosion of the land base continued. North Dakotans are aware of the egregious taking of reservation land for the Pick-Sloan project. North Dakota gained Lake Sakakawea but the Three Affiliated Tribes lost the core of their productive land, their communities, and their social unity. Lake Sakakawea

took 289 or 357 Indian households and scattered their members. About 500,000 acres were taken by the federal government. Standing Rock Reservation also lost thousands of acres to the flooding.

Tribal governments tried to use courts to prevent the taking and then to at least gain compensation. At first, courts decided that Indian land could be taken at will; Indians were not eligible for due process. Later courts did decide that Indians should be compensated for the value of the land at the time of the taking in the 1950s. However, there could be no compensation for the destruction of the social fabric of the entire reservation. Non-Indians who lost their land to the Garrison project were compensated according to the Fifth Amendment.

By 1934 approximately 50 percent of the remaining 40,000,000 acres of Indian land had been allotted to individual Indians and the rest reverted to tribal government. Indians were used to owning land in private by the 1930s and continue to accept the principle. America had succeeded in converting individual Indians to the view that land could be owned by individuals—to the idea of private landownership. Indians retained the idea that even individually owned Indian land was part of the tribal patrimony and not to be sold to non-Indians…it remains trust land.

Tribal governments have tribal public lands just as states and the federal government have. Many tribal governments did their best to devise a means to use land for the good of their people but the Bureau of Indian Affairs continued to decide what was best for Indian land. The Bureau leased land and resources to non-Indians routinely. Bureau-negotiated contracts for coal exploitation on Crow, Navajo, and Cheyenne reservations were well below market prices. Ranchers and farmers leased land through BIA contracts at bargain prices. Often Indians were simply told that their land had been leased and they should live with it. The BIA kept the income in Individual Indian Accounts to use in the best interests of the Indians whether or not the Indians agreed. After years of litigation and efforts to change policy, the BIA retains the right of lease approval.

Continuing turmoil in Indian policies marked the post–World War II period. It heightened Indian resistance to land taking and germinated an ideology for previously existing but unarticulated views of the relationship of indigenous land to Indian cultures. From the crucible formed by America’s Termination policies, Indians used courts, political lobbying, political alliances, and appeals to America’s conscience to defend treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, and tribal land. The Termination Policy of the 1950s intended to free the United States from its Trust Responsibility to protect Indian lands and rights by abolishing reservations and forcing Indians to become just another minority. In fact, individual termination acts abolished dozens of small reservations and legally changed 13,000 Indians into 13,000 non-Indians.

Indian leaders developed a variety of tactics to contest land issues. The National Congress of American Indians, an organization unifying tribal government voices, led the way in the fight against Termination. There were “Fish-Ins” in the Northwest that culminated in recognition of tribal rights to harvest fish off -reservation, demonstrations in Wisconsin that led to a favorable court decision affirming off-reservation hunting and fishing rights that had been included in treaties, and the militancy of the American Indian Movement. In these cases, Indians asserted their traditional views about the usage of resources, not private ownership. Often, non-Indians reacted with violent opposition.

Another way that Indians drew support within Indian communities and from the general public was to articulate the theme of Indians as stewards, not owners, of the land. In this construct, traditional ideologies of balance and harmony for the entire world became the focus of Indian public campaigns. Many Indians voiced the opinion that land was sacred and could not be sold. Writers like Vine Deloria Jr. and the Pulitzer winner, N. Scott Momaday, drew on tribal traditions to describe the responsibility of humans to maintain harmony in nature. Sacredness of the land became a mantra for Indian activists, traditional spiritual leaders, and many non-Indians.

This ideology reinforced the validity of Indian defense of land, particularly the idea of keeping the reservation and the rights that went with the land. Indian people accepted it as a renaissance of traditional Indian thought. Many Americans accepted the ideology too and saw it as preferable to the materialism of American society.

Ideology and American guilt created a receptive foundation for gains in the protection of Indian lands. The alienation of Indian lands by government action

ceased. Treaty rights were affirmed by courts and congressional legislation, and many tribal governments initiated efforts to regain lost reservation land.

Current procedures for reservations to regain land include two possibilities. First, tribes can buy fee patent land (privately owned). Then the purchasing tribe needs to petition for the land to be put into trust by the Secretary of the Interior. Second, the federal government can reassign land from the public domain back to tribes. However these efforts to reacquire land run into a number of problems that return once again to conflicting views of landownership …just in a different sense than the original differences. Now the differences have to do with which government controls the land and its resources. Non-Indians often feel threatened by tribal efforts to assert jurisdiction and to reacquire land. After centuries of American privilege, it is quite natural for them to feel threatened and even betrayed as Indians try to change the rules. Many non-Indians have lived on the land for generations, own their lake cabins, have established governments, and have never been subject to tribal jurisdiction.

State and county governments naturally want to retain control of their land particularly because of potential jurisdictional issues and loss of tax revenue. Individual non-Indians are concerned that Indian jurisdiction and ownership will threaten their continued private ownership. It just is not right for Indians to take the state’s lands and resources according to the Americans. The Department of the Interior does not grant petitions to move land back into trust easily. Counties and states usually oppose tribal efforts and launch court cases to prevent it.

Tribes, on the other hand, see the regaining of their land as a core issue in tribal identity. They insist that the reacquisition of tribal land is rectifying centuries of injustice. Many traditionally oriented Indians insist that the land is sacred, particularly certain places like Bear Butte, and should be returned to tribes for proper stewardship.

With this brief background in mind, a return to the original question is appropriate. Can the diametrically opposed views of landownership be reconciled? The answer remains a qualified yes. Tribes have indicated their willingness to make sure that restoration of reservation borders would not penalize non-Indian owners. Indians accept two principles of landownership created by Americans: private property and government jurisdiction. In effect, tribes are willing to continue the arrangement that now exists as long as they have the jurisdiction over what goes on within their own borders. As long as American governments and Indian governments are willing to negotiate issues of landownership in good faith with respect, reconciliation of opposing views is indeed possible.

Greg Gagnon is an Associate Professor of Indian Studies at the University of North Dakota. Native Peoples of the Northern Plains: An Introduction to Indian Studies, will be published in August 2009. Dr. Gagnon has made several invited presentations at the annual Governor’s History Conference and has offered several programs for the North Dakota Humanities Council including “All of the Things You Ought to Know About Indians and Were Afraid to Ask.”