4 minute read

USING HUMOUR IN THE FOREIGN LANGUAGE

Humour can be a great tool to boost enjoyment and motivation in foreign language learning. It can help pupils develop skills in manipulating language at a high level, can improve understanding of deeper meaning and can help build up an appreciation of underlying culture. It can practice language in genuine contexts and provides memorable chunks of language. So how can humour be built into the learning experience?

In writing tasks at GCSE, pupils can include funny but authentic expressions or idioms to enrich their response and access the higher band of the mark scheme for complexity, though care should be taken to ensure the right context and to not ‘overdo it’. Here are a few Spanish examples which I encourage pupils to use:

Advertisement

Una montaña rusa – a Russian mountain (lit.) = a roller coaster

No me importa un pepino – It doesn’t matter to me a cucumber (lit.) – I am really not bothered

Encontrar tu media naranja – To find your half an orange (lit.) = to find your other half

Dormir a pierna suelta = to sleep with a loose leg (lit.) = to sleep soundly

Tener malas pulgas – to have bad fleas (lit.) = to be bad-tempered

Tomar el pelo – to take the hair (lit.) = to pull someone’s leg

Hay gato encerrado - there is a locked cat (lit.) = there’s something fishy going on

Levantarse con el pie izquierdo – to get up with your left foot (lit.) – to get out of bed on the wrong side

Costar un ojo de la cara – to cost an eye of the face (lit.) = to cost an arm and a leg

Hablar por los codos – to talk through your elbows (lit.) = to talk a lot

Writing a caption for a funny photo can be good, creative fun.

Pupils can be invited to write captions for funny photographs, such as these above.

Translations - ‘Aaaargh, no! More Spanish homework?’ ‘When my friends and I see a teacher outside of school.’ ‘Do you know who my favourite rapper is? Kendrick Llama [Kendrick Lamar]’

Placing jokes visibly around the classroom prompts pupils’ curiosity to work out the meaning. Pupils must understand the content of the entire joke before understanding the punchline. Written activities can also be used such as matching the punchline, guessing the punchline, writing their own punchline, matching up endings to different jokes, and “jocloze” exercises (filling in the gaps). Some examples follow.

Jokes to work out the meaning:

¿Qué hace una abeja en el gimnasio?

Zumba.

What does a bee do in the gymnasium?

Zumba [Zumbar = to buzz]

¿Cómo se escribe ‘nose’ en inglés?

No sé.

¡Correcto!

How do you write ‘nose’ in English?

I don’t know [No sé in Spanish)

Correct!

¿Cuál es la fruta más divertida?

La naranja ja ja ja ja.

Which fruit is the most fun?

The orange (ja = ha).

¿Cuál es la fruta más paciente? Es pera.

Which fruit is the most patient?

It’s a pear (espera = wait).

Matching the punchline (translated due to length of text):

1. Teacher: Name one important thing we have today that we didn’t have fifteen years ago.

Pupil: _________________________________________

2. Pupil: Would you punish me for something I didn’t do?

Teacher: Of course not.

Pupil: __________________________________________

3. Son: Dad, can you write in the dark?

Father: I think so. What do you want me to write?

Son: ____________________________________________

4. Teacher: Well, at least there’s one thing I can say about your son.

Parent: What’s that?

Teacher: _________________________________________ a. Good, because I didn’t do my homework. b. Your name on this report card. c. Me. d. With grades like these, he couldn’t be cheating.

Guessing the punchline:

Profesor: Si tuvieras una libra y le pidieras otra a tu padre, ¿cuántas tendrías?

Alumno: Una.

Profesor: ¡No sabes matemáticas!

Alumno: ¡Usted no conoce a mi padre!

Translation:

Teacher: If you had a pound and you asked your father for another, how many would you have?

Pupil: One.

Teacher: You don’t know Maths!

Pupil: You don’t know my father!

This is a good opportunity to highlight the differences between the two verbs ‘to know’ in Spanish: Saber (a fact) and Conocer (a person/place). This is also similar to French.

Cartoons such as the simple Mafalda strip below illustrate the use of structures such as ‘tener que + infinitive’, the irregular form of ‘tener’ in the preterite tense and vocab such as ‘dentro de’ and ‘hermosa’.

Father: And in a few days we will have a beautiful plant

Mafalda: Why did you have to tell me the ending!

Riddles and tongue twisters such as ('Tres tristes tigres comían trigo en tres tristes platos sentados en un trigal') ('Three sad tigers were eating wheat on three sad plates placed in a wheat field') develop fluency in pronunciation.

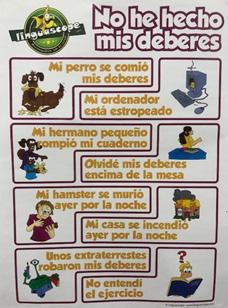

Reading or creating excuses in the target language for not doing homework is a great opportunity to practice the Spanish preterite (simple past), and another activity making funny excuses for not going out with someone is an equally good opportunity to practice the verb Poder (to be able), negatives and the Present Continuous.

Games such as ‘Regalos’ (‘Presents’) involve pupils throwing a dice and subsequently moving round a board landing on different pictures, picking up a card and then justifying why they have given that item to that particular person – for instance a pair of slippers (unas zapatillas) to a friend who has a collection of shells (conchas). How might you justify these further examples, if you were playing the game?

A skateboard for a teacher with a broken leg; Binoculars for an aunt who has lots of jewels; A guitar for an 85 year-old woman; A teddy bear for a friend who is always hungry.

Encouraging spontaneous writing or speaking through humour is therefore a great way to develop linguistic skills. If a pupil genuinely wants to speak or write something in the language to communicate then he/she will try harder to do so. And that hopefully will also reduce the sensation of being overly ‘self-conchas’ at the same time (pun intended!).

Mr G Stephenson