5 minute read

Nathan McGill - The Power in Participation, in Conversation with Wendy Ewald

Nathan McGill

The Power in Participation, in Conversation with Wendy Ewald

Advertisement

Wendy Ewald, often regarded as the founder of socially engaged photography, is a USbased photographer who collaborates with her participants to shift power dynamics. Today, we are discussing the power in participatory art and its purpose within the photography industry.

Nathan McGill (NM): How would you describe what socially engaged photography (SEP) and art practice is to someone who is unaware of the genre?

Wendy Ewald (EW): I get very uncomfortable when people ask me that, and I’ll just sort of say...I work with communities, women and children. I’m very interested by tensions between or within communities and how photography can be used for that; I am very interested in education, because it’s about relationships and power. I’m very interested in power, who has the power and how you can play around with that in order to use the visual medium of photography as a means to interpret the world outside of one person; so that students can look at the same glass and see it differently - that’s also a big help at forging a more democratic classroom.

NM: So Wendy, you’ve told me what SEP is, but where does its origin actually begin? WE: I think one is anthropology, that’s what people were doing in the early days and I thought I needed a degree in anthropology. The idea of understanding how people see things differently - that’s a big part of socially engaged photography to me, because if you’re not going to honour or make transparent how people see things differently, how can you be socially engaged if you have one point of view?

NM: Could you tell me how collaborative photography, SEP or however you prefer to define it, is more ethical in representing individuals/ communities than other areas of photography?

WE: It’s asking the subject to participate in the message, in the framing of the message and the design of the message. I think as a photographer, you have certain skills that help people understand how they can use these mediums. Some people do have the idea that all you have to do is give camera and film to people as that is the pure form and that is what should be done. But I do believe that is using people too, that it is not that ethical either. Then you’re saying this is who they really are, and you haven’t given them the tools in an educated way so they can use them.

NM: It’s clear that education is significant in all your seminal works, but what was important to you when facilitating projects with communities outside of your own?

WE: It’s really important to spend time and for one thing, to be open. I don’t really like to read too much before I go places, as I then form ideas from my own experiences outside of that place. So, it’s a gradual process, it’s like having to wipe the slate clean on how I’m seeing the place and people. I do have ideas as I can’t start from nowhere, but then leave it open for how to perceive. I make mistakes and have to acknowledge those, then ask for help. One example of this is when I was in Morocco, normally I have a pattern I may use so start with self-portraits, then go to family, community or dreams or families. But in Morocco, self-portraiture is a little hard to do. Students enjoyed photographing families, that’s the most important thing. I then asked them to photograph their community and I asked: “are you sure you want to do this? This is difficult to go out with a camera because of the views of photographing people.” They said: “yeah no problem”, but, when they came back the pictures were blurry, and they knew how to use the camera very well. I realised that I best sit down and have a conversation about what had happened, and so I reported it. I was appalled that I had been the source of that conflict. There’s always the danger of being too paternalistic - that was a mistake even though I didn’t think it was a mistake.

NM: What drove you to work with the communities involved in both Retratos y Suenos and Portraits and Dreams?

WE: In Kentucky, because it’s a very old community, I was really interested in where people from Ireland and Scotland moved in the 1800s because of the famine. There were all these mountains and no one could move around; they were just there. Their way of speaking was very old English and their accent was something you couldn’t understand at first. They also still ploughed with a horse and a hand plough. They didn’t have telephones either. There was a group there I went to work with, called ‘Appalshop’. It’s a multimedia cooperative that started in 1969 as part of the war on poverty.

I Dreamt I Killed My Best Friend, Ricky Dixon (Allen Shepherd, 5th August 1982, Portaits and Dreams)

WE: So that’s why I went, because I was interested in the place and they were a really interesting group to work with. When I went to Mexico, it was a different situation because I was asked by the Polaroid corporation to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Columbus which is not a politically correct thing to do because Columbus was the big colonial master.

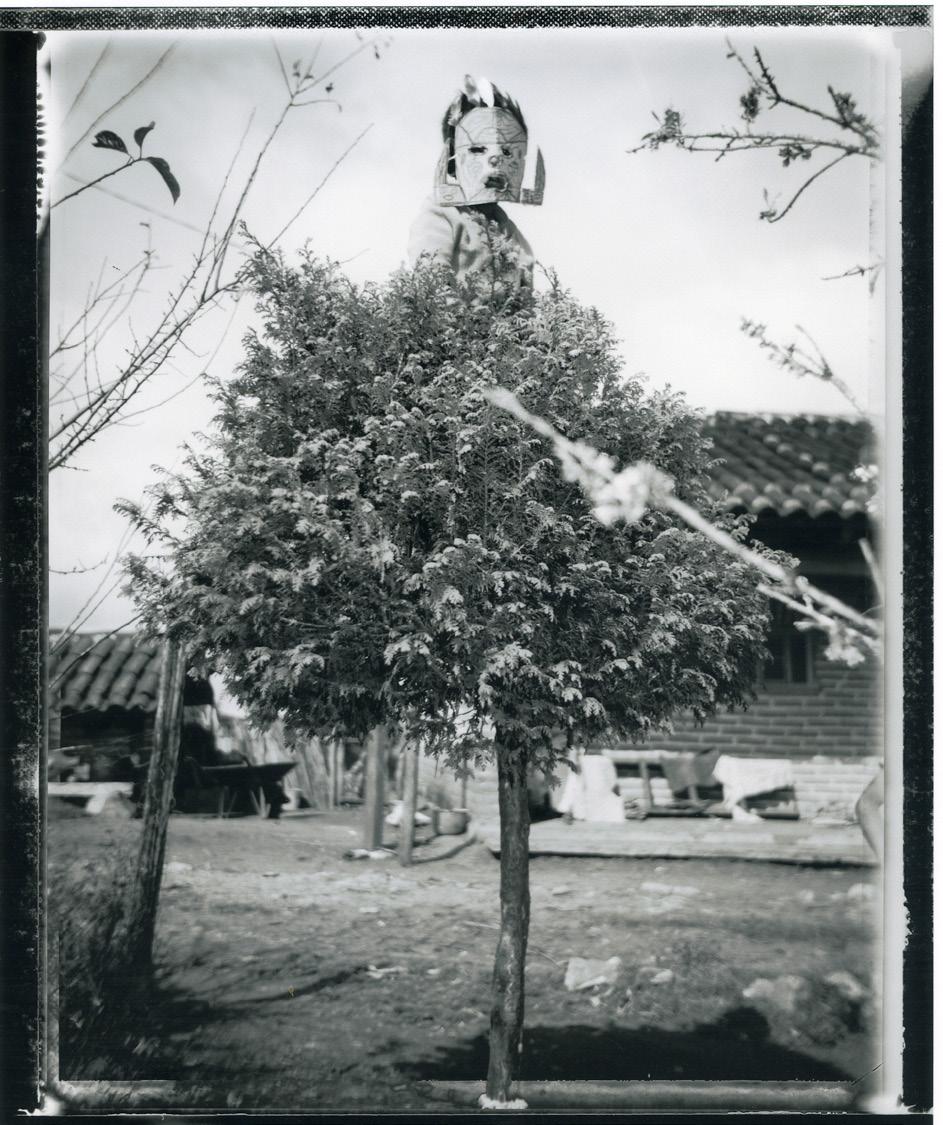

The Devil is Spying on the Girls (Sebastian Gomez Hernandez, 1991 Retratos y Suenos)

WE: I was interested in going to Mexico and I knew some people who had worked in Chiapas, which is very indigenous. A lot of the work I do comes from knowing people in places. One thing that was very interesting was that the Mayan community and the Ladino community, which were the Spanish descendants, was split in their communities, so I worked in groups with Spanish speaking and Tzotzil speaking (the Mayan language). The Mayan culture is fascinating and dreams mean a lot to the Mayan culture, so they really took off with that. The strongest pictures out of all the young people I have worked with, are from those two communities.

NM: And finally, to end our interview, why is changing the power dynamic important to you?

WE: I think you can get much deeper when you give up that power and you leave space for participants; you get much visually richer and informationally richer images. Frankly, I was pretty bored by photography after a bit. I loved it when I started, but it became too predictable and I wanted to be learning all the time. That’s the type of work I wanted to share. I think allowing me to give up some of my control makes it a much wider and deeper vision of the place, the person. I want to be surprised and it gives you the space to be surprised; rather than just having an image in your head that you’re trying to reproduce.