5 minute read

Clare Hewitt - Behaviour to Remember

Clare Hewitt

Behaviour to Remember

Advertisement

If you’ve ever encountered a Mimosa pudica (translated as sensitive plant), you might have touched or shaken its leaves to see them transform, folding inwards in response. In 2011, ecologist Dr Monica Gagliano conducted an experiment to explore whether the Mimosa pudica’s tendency to droop when perceiving threat was an instinctual reflex or if the plant could, “truly learn from new experiences and flexibly alter her behaviour.” (page 59 from her book Thus Spoke the Plant). Gagliano thought that to do so would indicate the plant’s presence of memory and ability to learn.

She performed 15 centimetre controlled drops on the plants in a variety of scenarios. As expected, when initially dropped, the plants responded by closing their leaves. However, after four to six drops, each plant stopped folding and continued this way for a total of 60 drops. They had learned there was no apparent threat and it was unnecessary to reduce their capacity to forage for light. Importantly, when Gagliano repeated the experiment three days later, each plant kept their leaves open from the first drop onwards.

Controlled drop system for habituation training of Mimosa pudica plants (Gagliano)

As human beings, we commonly associate memory with brain-wide processes of encoding, storage and retrieval. Gagliano views it differently, stating: “Because memories are born of and come into existence within and through relationships of all kinds...I saw memory as a feature of a truly ecological, dynamic process of relationships, where meanings emerge to shape the production of behaviours that, in turn, shape new interactions for new meanings to emerge.” (page 67, Thus Spoke the Plant).

The Dog’s in the Car (Aftab 2019)

In Tami Aftab’s work, The Dog’s in the Car, we are introduced to her father Tony, who suffers with hydrocephalus, an abnormal build-up of fluid in the ventricles of the brain. 25 years ago, during an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (an operation to bypass blockages), an internal bleed occurred which permanently damaged his short term memory. Through her exploration of behaviour, experience and collaboration, we can recognise Aftab’s practice as akin to Gagliano’s understanding of the process of memory.

Over the years, Aftab and her family have developed methods of communication to support her father in his forgetfulness. Tony writes repetitive phrases on his hands and Post-it notes are placed throughout the house, in his wallet, on doors, including reminders like; ‘The dog’s in the car, Turn the oven off, and Put your teeth in’. These are personal memos, small squares, impermanent, existing in the confines of the home. Their purpose is to be helpful, not to be photographed. To visualise them, Aftab took the phrases and cut them out as large letters, painted them, connected them with string and hung them in context; outside the front door for when Tony left the house: (‘TURN THE OVEN OFF’), or in a bush in the park for when he thought he’d lost the dog: (‘THE DOG’S IN THE CAR’). Small gestures are transformed into performative sculptures, each given their own theatre in which to amplify the intricacy of familial coping mechanisms.

These themes of amplification and performance run skilfully through each photograph. Far from “sensitive” Gagliano identified Mimosa pudica as “a grand performer” (page 56 Thus Spoke the Plant) and Aftab encourages her father to be the same. When she asked him how he described his memory loss to other people to help them understand his condition, he said he tells them he walks up and down the stairs because he’s forgotten what he’s looking for. When she asked him to show her that, he struck a pose that she wanted to place on a stage and shout about, so they went to the local village hall and photographed him performing and exaggerating his body in motion climbing imaginary stairs.

Up and Down the Stairs (Aftab 2020)

My initial reaction to The Dog’s in the Car was a sense of familiar amusement. I could identify with the closeness between Aftab and her father that enabled the creation of this work. In Why People Photograph Robert Adams states: “Intentionally funny pictures that remain funny are unusual because they are hard to make, because the life that facilitates them is hard to live. Wit and good humour are both traceable to a sense of incongruity, but good humour requires more - acceptance.” In 1990, on the night Tony met his wife-to-be in Henry’s Bar, Richmond, he asked for her number after they’d sparked a conversation. She recited it but wasn’t sure if he’d call because he didn’t write it down. A few days later, Tony called. He had a mind for remembering numbers and a first-class degree in mathematics. Looking at this work, you know you are viewing the same man that memorised his future wife’s telephone number, such is the embrace of complexity of character embedded in the photographs. Aftab refuses to perceive ‘disability’ as ‘less than’. She has beautifully translated what it means to see her father, to understand how best to reinterpret their memories into their present and to take pride in revealing him to her audience.

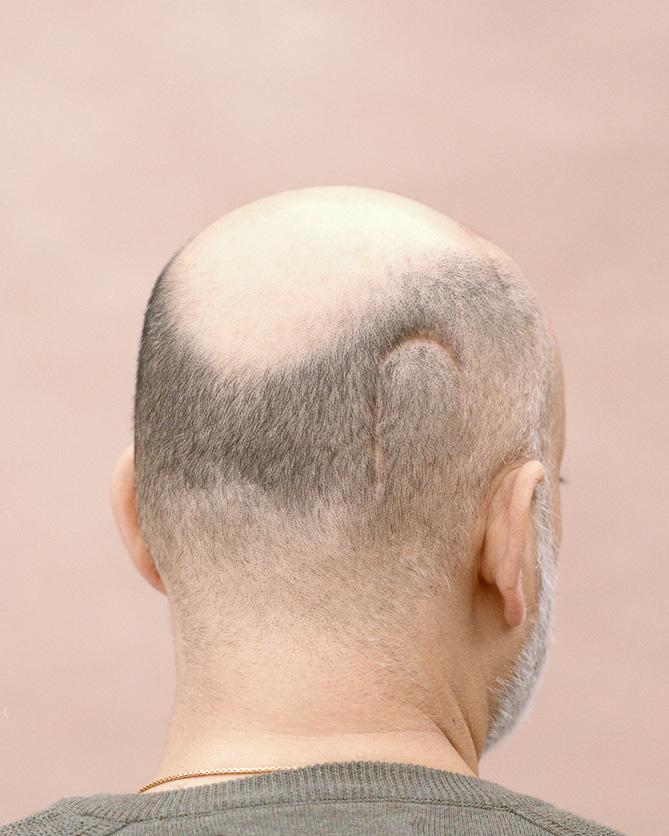

In daily life, Tony’s confidence is sometimes confined because he’s unsure of what’s true and what’s false. In front of the camera he radiates his self, dedicated to his daughter and their artistic vision. It’s an exchange in which Aftab portrays her father at his most magnified. Robert Adams also states that photographs remain funny because: “the pictures are given to us by all parties, and so invite affection and identification rather than ridicule.” Aftab’s practice operates as a genuine collaboration. During lockdown, she found it impossible to create the work without her father present. The space between them didn’t exist without him close. Depicting his scar through the natural form of a plant was her only mechanism to attempt to fill that space.

Scar (Aftab 2020)

Tracing the Shape of Dad’s Scar (Aftab 2020)

In response to Monica Gagliano’s work with Mimosa pudica, many scientists believed that memory couldn’t exist in plants. They were comparing non-human behaviour with human biology, treating the latter as superior. Gagliano stands in awe of the plant’s abilities, rather than anticipating its failure. She states: “unlearning distinctions...doesn’t mean that differences are not useful. What it does mean is that we stop being obsessed with them to the point that we cannot see anything beyond them and thus miss the incredible richness of qualities and characters of both the human and the non-human world.” (page 71 Thus Spoke the Plant ). By amplifying all the unique elements of her father and relaying that memory not only exists cerebrally but also through relationships, behaviour and performance; Aftab portrays what is possible in a state of true acceptance.